Abstract

In studying second language (L2) learners’ motivation, much research has focused on belief in one’s ability to succeed at achieving language proficiency. However, only limited research has examined whether learners’ L2 self-efficacy is related to integrative motivation, or whether it is related to English achievement in a foreign language context. In this study, we investigated whether integrative motivation mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and English achievement, employing data from 102 eighth-grade adolescent learners in Korea. In a mediation model, with the relations among self-efficacy and integrative motivation variables examined simultaneously, there was definitive evidence that self-efficacy directly influenced English achievement. Adolescent L2 learners’ self-efficacy influenced English achievement indirectly through its effect on integrative motivation. Adolescents with higher self-efficacy reported more integrative motivation, and greater integrative motivation was associated with higher English achievement. The findings suggest that an L2 learner’s integrative motivation plays a prominent role in the relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and English achievement in a foreign language classroom.

摘要

在研究第二語言(L2)學習者的動機時, 許多研究都聚焦在關於語言能力自我信念的議題。然而, 少有研究探討外語學習者的自我效能是否與整 合型動機有關, 或者是否與外語學習成就有關。本研究採用了韓國102名八年級青少年的數據, 探討了綜合動機是否在自我效能和英語成就之間 產生中介效應。在中介模型中, 自我效能和整合型動機這兩個變量同時被檢驗, 有明確的證據顯示自我效能直接影響了英語成就, 且青少年第 二語言學習者的自我效能藉由對整合型動機的影響間接地影響英語成就。自我效能感較高的青少年能有更多的整合型動機, 而更大的整合型動 機與更高的英語成就亦存在著顯著相關。研究結果顯示, 在外語的課堂中, 第二語言學習者的整合型動機在自我效能信念與英語成就間扮演了 顯著的角色。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The individual difference factors of second language (L2) learning that have attracted the interest of researchers include anxiety, language aptitude, learning style, personality, motivation, and working memory, as well as the use of language learning strategies. Among various individual factors, the development and maintenance of motivation has been considered a key indicator of success for L2 learners [1, 37]. One of the most widely investigated individual variables in L2 research, motivation is a dynamic, fluid, and evolving concept; it is not static. The concept of motivation is grounded in socio-cognitive views (e.g., expectancy-value theory) which offer explanations about how individuals are influenced in their decision-making processes by their individual achievement choices and performances [12] and contextual elements such as instructional context (e.g., task type) and social relationships (with, e.g., teachers, parents, peer group) [10].

The basic premise of learner motivation is that differences in motivation lead to differential success in language proficiency. Multiple research syntheses summarizing myriad empirical studies support the generalizability of the positive relationship between motivation and successful L2 learning [6, 7, 33, 37]. Given such robust empirical support for motivation, one might assume that all types of motivation orientation are equivalent. However, this would be a mistake. Motivation is multifaceted in nature and not a unitary construct.

Although a wide range of motivation frameworks has been developed over the decades, there is scarce research investigating self-efficacy and integrative motivation, two sub-dimensions of motivation, and their respective roles in L2 achievement. The present study—a survey of middle school students who report having studied English as a foreign language—aims to address this gap and provide new insights regarding L2 motivation in English as a foreign language (EFL) context.

Theoretical and Empirical Background

Expectancy-Value Theory

This research draws on a theoretical foundation of expectancy-value theory. Initially developed by Atkinson [2], the expectancy-value theory is a leading theory of motivation that has guided a wealth of research over the past four decades [12]. The main factors in the expectancy-value theory are “an individual’s expectancy of success in a given task, and the rewards that successful task performance will bring” and “the value the individual attaches to success on that task, including the value of the rewards and of the engagement in performing the task” [10 , p. 13]. An individualist perspective about one’s performance on an upcoming task is the “self-concept of domain specific ability” [12 , p. 3], which is similar (despite the slight conceptual difference) to what Bandura calls personal efficacy in his theory [55]. Expectancy is often equated with academic self-concept e.g., [19]. While expectancies and values may vary based on perceptions and previous experiences, they are not alienated from “a variety of socialization influences” [55 , p. 69] or “situational or contextual factors” [57 , p. 658].

Theoretically grounded in expectancy-value theory, the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) [43] was developed to represent students’ processing of information based on their beliefs and perceptions regarding educational inputs and tasks [11]. The MSLQ contains items with a 7-point Likert scale that assess a student’s expectations for a course and expected value of the course, as well as anxiety, cognitive and metacognitive strategies, and resource management. Initially developed to measure the motivation and learning strategies of college students at the course level [43, 44], the MSLQ and variations of it have been used to measure motivation in various contexts and for various purposes [11]. The present study adapted six items from the MSLQ to a foreign language context (middle school students in Korea) to assess learners’ self-efficacy and integrative motivation.

Self-efficacy and Academic Achievement

Self-efficacy refers to “beliefs about one’s capability to learn or perform effectively, and self-efficacy for learning refers to beliefs about using self-regulatory processes, such as goal setting, self-monitoring, strategy use, self-evaluation, and self-reactions to learn” [59 , p. 398]. Bandura [5] argues that beliefs of personal efficacy is the most central mechanism in human agency as “a key personal resource in self-development, successful adaptation, and change” (p. 4). The expectancy-value theory also postulates that an individual’s beliefs about how well they will do on a task and the extent to which they value achievement on it can explain their actions, persistence, and performance [e.g., 2, 12, 55, 56]. How learners perceive their competence about their goals is a robust predictor of successful educational outcomes [e.g., 4, 20, 25, 39, 42, 46, 58], since people generally do not take action on certain tasks if those tasks seem to be beyond their coping abilities [3]. In sum, self-efficacy directs learner engagement both in cognitive and behavioral ways, and motivation can be derived from these processes in terms of activation and exertions of behaviors [3]. In an actual learning situation, aspects of motivation include personal interest (i.e., intrinsic motivation), task value (i.e., importance of the task to the learner), affect (i.e., learner’s emotional experiences), and learning situation [35]. All of these components are correlated to one another, and their relationship is believed to be reciprocal—together, they contribute to more learning and higher attainment [35].

A wealth of research has shown the positive association between individual self-concept and academic achievement in various educational contexts [6, 30, 47]. Consequently, in their meta-analysis of previous scholarly work, Möller, Zitzmann, Helm, Machts, and Wolff [38] found that academic achievement strongly affected individuals’ self-concept, both within and between subjects.

Among individual analyses featuring L2 learners, Hsieh and Kang [23] examined 9th graders and their fluid motivation in a Korean EFL context. They found a significant relationship between the students’ English test scores and their degree of self-efficacy. Students who exhibited a higher sense of self-efficacy were more confident that their abilities and time invested were reflected in the test results. In contrast, students with lower self-efficacy were more likely to report external factors out of their control as determinants of their English score. Similarly, Bong [6], in her study of Korean high school girls’ motivation, also found that high-achieving students’ self-efficacy after taking exams led them to stronger self-efficacy in subsequent semesters. Erler and Macaro’s [13] study found that learners with a high degree of self-efficacy exhibited motivation to learn the second language they were studying beyond the course requirements. However, their self-efficacy beliefs did not necessarily correlate with their actual linguistic ability on assigned tasks.

Research has also undertaken cross-national comparisons. Chen and Zimmerman [8], for example, investigated two groups of middle school students of different nationalities, American and Taiwanese. They found that students’ perception of their abilities played an essential role in successful performance in mathematics. Taiwanese students reported greater self-efficacy on math questions of both moderate and high difficulties. Their performance on the math tasks was slightly better than their American counterparts, exhibiting an accurate self-report of self-efficacy. In a similar vein, Wang, Schwab, Fenn, and Chang [53] examined two groups of college EFL students, Chinese and German. They found that both the self-efficacy beliefs of both groups of students were positively related to English test scores. Interestingly, the Chinese students in the study displayed a significantly lower degree of self-efficacy than their German counterparts, indicating that culture may play a role in self-efficacy beliefs.

Consistent with expectance-value theory, it seems reasonable to expect that individuals’ beliefs about how well they will do at a language will predict domain-specific academic achievement.

Integrative Motivation and English Achievement

In his pioneering research, Gardner [14] identified a socioeducational model in second language study: integrative motivation. Originally suggested in the bilingual context of Canada, where psychological assimilation into a target linguistic community is especially plausible, integrative motivation is defined as a favorable attitude towards an L2 community and an inclination to interact with and become part of that community [17]. Thus, it is assumed that individual differences in terms of integrative motivation will align with individual differences in attitudes towards the given language learning context [16, 18], consequently affecting L2 achievement. Central to this concept is the idea that learning a language other than one’s first language (L1) requires openness toward the culture that the second language embraces [37].

As Gardner [16] has pointed out, the more recent definition of integrative motivation embraces broader concepts than those often originally defined. Integrative motivation involves “not only the orientation but also the motivation (i.e., attitudes toward learning the language, plus desire plus motivation intensity) and a number of other attitude variables involving the other language community, out-groups in general and the language learning context” [14 , p. 54]. Integrative motivation also “reflects a genuine interest in learning the second language in order to come closer to the other language community” [15 , p. 5].

However, empirical evidence on the role of integrative motivation in L2 learning has not been robust in foreign language learning contexts where the target language is primarily learned in classroom contexts and rarely used as a medium of communication. Previous research has suggested that integrative motivation may not play a key role in L2 learning when communication with the members of the target linguistic-cultural community is not an integral part of the educational process [e.g., 9]. For example, Warden and Lin [54] found a lack of integrative motivation in a Taiwanese EFL context. In their study, instrumentality (e.g., getting a promising job) played the most important motivator for learning English. It was assumed that learners in EFL contexts, unlike ESL contexts, are separated from the target culture, lacking experiences or opportunities that allow them to assimilate into the target linguistic group, and thus lacking integrative motivation as well [e.g., 9, 40, 54].

On the contrary, however, integrative motivation does appear to be a significant differentiator of achievement in foreign language learning contexts. For example, Hernández [22], in his study of college students learning Spanish as a foreign language, found that integrative motivation was a significant predictor of oral proficiency. Students with integrative motivation worked to sustain their L2 learning by taking classes beyond the required level. Li and Pan [34] found that high-achieving college students displayed a higher degree of integrative motivation in a Chinese EFL context. In contrast, instrumental motivation (i.e., pragmatic gains as a result of L2 learning) was exhibited at a similar level between high and low achievers. With respect to Korean EFL contexts, a few studies [e.g., 29, 36] explored the role of integrative motivation. Makarchuk [36] investigated Korean EFL college students’ motivation, focusing on integrative and instrumental motivation. In a survey asking the most important reason for learning English, the participants displayed strong motivation with regard to their future careers and their opportunities to communicate orally with L2 speakers.

Extending these findings, we investigate the extent to which students want to learn English for integrative reasons (e.g., to converse with English-speaking individuals) predicts academic achievement (among adolescent learners of English as a foreign language).

Integrative Motivation and the Relationship Between Self-efficacy and English Achievement

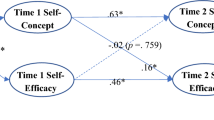

The body of research reviewed above offers an understanding of the relationship between learners’ self-efficacy, integrative motivation, and English achievement, and indicates the possibility that integrative motivation plays a role in achievement within a foreign language learning environment. The present study is an initial attempt to investigate whether a motivated individual’s strong desire to learn more about a target language is a response to the relationship between their perceived self-efficacy and their actual ability to succeed at learning English. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to empirically test this model in a foreign-language learning environment in Korea (see Fig. 1).

The Present Study

Although the majority of previous research has found significant relationships between self-efficacy and success in the learning of a second language, investigation into whether integrative motivation is likely to mediate self-efficacy and English achievement is noticeably lacking in the literature. The present study addresses this gap and contributes new empirical evidence from a survey of middle school students who report having studied English as a foreign language. This study asks the following research questions:

-

(1)

What is the relationship between self-efficacy, integrative motivation, and L2 English achievement?

-

(2)

What are the effects of self-efficacy and integrative motivation on L2 English achievement?

-

(3)

Does integrative motivation mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and L2 English achievement?

Method

Sample

Participants were eighth-grade students enrolled in a public middle school serving a middle-income population. The sample consisted of 102 students (51% female) and at the start of the study, these students were 15–16 years old. All the participants in the study had been studying English as a foreign language for the last 5 years, as recommended by the Korean Ministry of Education [32]. The students were in four classrooms, which ranged from 24 to 26 students per class.

Measures

Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire

A modified Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) [43] was used to measure these adolescent learners’ motivation to learn a foreign language. It comprised six items falling into two sub-dimensions: self-efficacy (“I’m certain I can master the skills being taught in this class,” “I expect to do well in this class,” and “I’m confident I can do an excellent job on the assignments and tests in this course”) and integrative motivation (“Studying English is important because it will allow me to meet and converse with more people,” “Studying English will allow me to travel to gain experience abroad,” and “Studying English will help me to broaden my network of friends”). Responses were graded on a five-point scale (1 = never true of me and 5 = always true of me), with higher scores indicating higher usages of motivational strategies. Adequate reliability and validity data have been obtained. The sum of item-to-total correlations scale ranged from .28 to .73. The Cronbach alpha reliabilities for self-efficacy and integrative motivation were .76 and .88, respectively. Together, reliability for both sub-dimensions was .79.

English Achievement

The English achievement score was measured by teacher-developed tasks that assessed knowledge of listening, reading, speaking, and writing skills. Course grades were obtained from the students’ school records.

Procedure

This study was conducted at the beginning of the spring semester of the students’ eighth-grade year. The initial questionnaire lasted approximately 20 min and was completed during English subject class time.

Data Analysis

The analysis was carried out in three stages. First, we computed the descriptive statistics of the two sub-dimensions of motivation and conducted Pearson’s correlation analyses with the same variables. Second, an ordinary linear squared (OLS) regression analysis was conducted to examine if motivation subdimensions predicted L2 learners’ English achievement. Finally, our path model hypothesized that integrative motivation mediates the relationship between self-efficacy and English achievement, and this was analyzed using mediation analysis in STATA 16 [51]. Mediation analysis was employed to examine the direct and indirect associations of self-efficacy and English achievement using the full maximum likelihood method of estimation. Moreover, we carried out 5000 bootstrapped samples to construct bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for both correlation analysis and indirect effects. The bootstrap procedure is a powerful method to address the shortcomings of the confidence interval methods of testing an indirect effect. With smaller sample sizes, for example, the bootstrap method is less likely to generate false positives [31, 45, 52] and, therefore, inaccurate type I error rates.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis for all the variables in the study. Skewness and kurtosis indicated no normality violations and no influential outlier data points were found. The table also summarizes the bivariate correlations between sub-dimension measures and English achievement score. Specifically, bivariate correlation analyses indicated English achievement was positively and significantly associated with self-efficacy (r = .38, 95% bootstrap CI =.21 and .56) and integrative motivation (r = .42, 95% bootstrap CI = .26 and .57). This suggests that learners who had higher achievement felt more efficacy and integrative motivation than their lower achieving counterparts.

Predicting English Achievement in L2 Learners

To examine the unique contribution of self-efficacy and integrative motivation in explaining individual variance in English achievement, we conducted OLS regression analysis. The analysis revealed that both self-efficacy, β = 1.89, p < .001, and integrative motivation, β = 1.64, p < .01, positively predicted English achievement in the L2 adolescent sample. The model including those two predictors accounted for 24% of the variation in English achievement.

Mediation Analysis

For the mediation models, we assessed whether integrative motivation mediated relations between self-efficacy and English achievement (see Fig. 2). Results from mediation analysis revealed that adolescents’ self-efficacy exerted a significant positive effect via integrative motivation (a path = 0.53, p < 0.001), and this increased the extent to which their integrative motivation was related to English performance (b path = 0.33, p < 0.001). So self-efficacy indirectly increased English achievement performance through integrative motivation (indirect effect or ab = 0.17, 95% bootstrap CI = 0.094 to 0.264 based on 5000 bootstrap samples). After accounting for this mechanism, there was a significant positive direct effect of self-efficacy on English achievement (direct effect or c’ path =0.28, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.937 to 3.002).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to address the lack of previous research on foreign language achievement with regard to two sub-dimensions of motivation (i.e., integrative motivation, self-efficacy) and English achievement of L2 learners. In short, we found that L2 learners’ self-efficacy influences adolescents’ English achievement indirectly through its effect on integrative motivation. Adolescents with higher self-efficacy reported more integrative motivation, with greater integrative motivation associated with higher English achievement. In addition, there was definitive evidence that self-efficacy directly influenced English achievement.

While the previous findings have shown the relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and English achievement [e.g., 6, 23, 24], our analyses uncovered that integrative motivation among L2 learners was an important factor for understanding this relationship in English achievement associated with self-efficacy. Prior studies have shown lack of integrative motivation in foreign language contexts [e.g., 54]; however, our results are also in keeping with previous study that English proficiency was positively correlated to integrative motivation and self-efficacy beliefs, indicating that students with higher proficiency exhibited a greater degree of both types of motivation 48].

A sociocultural lens may be useful for understanding the importance of integrative motivation, especially when the opportunities to communicate with the L2 community are rare in foreign language contexts [e.g., 9, 40, 54]. In South Korea, English has been the preferred foreign language for decades, despite the fact that very few people there speak English as a native language. However, a high score on the English subsection of the Korean College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT)) is synonymous with strong academic achievement and leads to matriculation into prestigious colleges. Consequently, many students attend extra English classes at private academies called hakwon to enhance their English proficiency. English-medium kindergartens and schools are also becoming more popular despite onerous tuition fees. In sum, the perceived importance of English in the school curriculum is high at all grade levels, both among students themselves [26] and their parents.

Traditionally and consistently, English teaching and learning in Korea primarily consists of reading and grammar instruction taught through a translation method, which aims to improve the abilities required for the College Scholastic Ability Test [49]. However, it would seem this approach results in low integrative motivation. In fact, in Korea’s high-stakes, high-pressure, exam-oriented culture, many students report learning difficulties and demotivation [28, 50]. For example, Song and Kim’s [50] study, which investigated Korean high school EFL classes, revealed that most participants had begun suffering from a lack of motivation at the junior high school level, in large part because of English instructors and their “grammar and translation” teaching method.

In a system where getting good grades and high exam marks is all that matters [e.g., 27], it is harder for students to feel the value of learning English, or feel connected to or interested in the “other language community.” A preoccupation with standardized tests can lead to a vicious cycle of low motivation and low achievement. To break this cycle, and boost integrative motivation, students need to be encouraged to find what learning English means to them, and to their future, through authentic L2 learning materials.

Limitations

The present study is not without limitations. Though the sample size is a strength, other qualities of the data may present some limitations. For example, the fact that adolescents in our sample are from a metropolitan public school limits our ability to generalize our findings beyond urban contexts. In addition, due to time constraints, a modified MSLQ was administered to the students. While the modified scale reliability was adequate, relying only on one questionnaire is not desirable. Similarly, other sub-dimension scales of motivational strategies should be explored. Also, in-depth individual interviews would have shed more light on motivating and demotivating factors, providing a more comprehensive picture of these Korean EFL students’ L2 learning.

Pedagogical Implications and Future Directions

To help support students of lower achievement become better learners of foreign language, ways in which English subject teachers can foster and encourage enthusiasm for learning and self-efficacy beliefs in the classroom should be explored. As our research findings indicate, the role of integrative motivation in EFL classrooms needs to be more seriously considered, as evidence has shown that integrative motivation mediates self-efficacy beliefs and success in L2 learning.

English teaching and learning in the current Korean educational environment focuses heavily on getting good scores in high-stakes exams, minimizing the opportunities for students to explore new cultures alongside L2 learning. Through various authentic materials, students may develop genuine interests related to language learning and possibly find a link between English in the classroom and English beyond the classroom. For example, new approaches to language teaching and learning such as CLIL (content- and language-integrated learning) in Europe appear to raise learner motivation [e.g., 33], calling for a need to investigate alternative teaching approaches that might work in Korean EFL contexts.

On top of that, students need to be supported to enhance their self-efficacy.

As mentioned earlier, breaking a vicious cycle of low motivation and low achievement is crucial since self-efficacy beliefs are closely related to past experiences. Learners may hesitate to take action when a challenge appears to be beyond their ability to cope [3]. In this sense, teachers should help low-achieving students set a specific goal to try and then achieve their own goal, thus feeling a sense of achievement. Accumulating successful learning experiences will positively affect learners’ attitudes toward L2 learning, thus playing a role in enhancing their self-efficacy. Gradually, students will be more likely to move toward bigger goals, which may bring success in subsequent tasks. Hence, to sustain motivation in L2 learning, teachers should help their students set reasonable, specific goals for themselves, rather than chasing after unrealistic goals determined by external social pressure.

According to Dörnyei and Ushioda [10], informational feedback on current performance enables students to self-evaluate their current status and become aware of what is needed for progress. Teachers’ feedback can also contain “a positive persuasive element” [10 , p. 127], helping students grow the belief that they can reach their predetermined goal. In addition, a teacher’s motivational practices (e.g., encouraging students, explicitly expressing class objectives) are closely related to students’ motivated behavior (e.g., alertness, participation, volunteering) [41]. It should be noted that a single strategy may not be sufficient to enhance students’ motivation, given the complex, fluid nature of classroom contexts [21]. Future research should also investigate teaching approaches—such as integrating communicative activities and introducing authentic materials that open doors for learning about new cultures—that show promise in boosting EFL learners’ integrative motivation.

Conclusion

Lack of motivation is an important educational concern. This study provides empirical evidence regarding two sub-dimensions of motivation and how they relate to adolescents studying English as a foreign language in a classroom reflective of current instructional practices in South Korea. Our results indicate that both efficacy beliefs and integrative motivation predicts English language achievement. This study also suggests the role that integrative motivation plays in mediating self-efficacy and English achievement. How to best help our students grow and sustain their interest in L2 learning in the face of social pressure remains a huge task both for teachers and researchers.

References

Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2018). The L2 motivational self system: a meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(4), 721–754. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.4.2.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64(6, Pt.1), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122.

Bandura, A. (2006). Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 1–43). Information Age Publishing.

Bong, M. (2005). Within-grade changes in Korean girls’ motivation and perceptions of the learning environment across domains and achievement levels. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(4), 656–672. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.4.656.

Boo, Z., Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). L2 motivation research 2005–2014: Understanding a publication surge and a changing landscape. System, 55, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.10.006.

Chen, P., & Zimmerman, B. (2007). A cross-national comparison study on the accuracy of self-efficacy beliefs of middle-school mathematics students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.221-244.

Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign language learning. Language Learning, 40(1), 46–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1990.tb00954.x.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2014). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Duncan, T. G., & McKeachie, W. J. (2005). The making of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire. Educational Psychologist, 40(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4002_6.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: a developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859.

Erler, L., & Macaro, E. (2011). Decoding ability in French as a foreign language learning motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 95(4), 496–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01238.x.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: the role of attitudes and motivation. Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 1–19). University of Hawaii Press.

Gardner, R. C. (2010). Motivation and second language acquisition: the socio-educational model. Peter Lang.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second language acquisition. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 13(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0083787.

Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A.-M., Tennant, J., & Mihic, L. (2004). Integrative motivation: changes during a year-long intermediate-level language course. Language Learning, 54(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00247.x.

Gaspard, H., Wigfield, A., Jiang, Y., Nagengast, B., Trautwein, U., & Marsh, H. W. (2018). Dimensional comparisons: how academic track students’ achievements are related to their expectancy and value beliefs across multiple domains. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 52, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.10.003.

Grolnick, W. S., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1991). Inner resources for school achievement: motivational mediators of children’s perceptions of their parents. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4), 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.4.508.

Guilloteaux, M.-J. (2013). Motivational strategies for the language classroom: perceptions of Korean secondary school English teachers. System, 41(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.12.002.

Hernández, T. (2006). Integrative motivation as a predictor of success in the intermediate foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 39(4), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2006.tb02279.x.

Hsieh, P. P., & Kang, H. (2010). Attribution and self-efficacy and their interrelationship in the Korean EFL context. Language Learning, 60(3), 606–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00570.x.

Khodadad, M., & Kaur, J. (2016). Causal relationship between integrative motivation, self-efficacy, strategy use and English language achievement. The Southeast Asia Journal of English Language Studies, 22(3), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2016-2203-08.

Kim, K.-J. (2016). Korean secondary school students’ EFL learning motivation structure and its changes: a longitudinal study. English Teaching, 71(2), 141–162.

Kim, T.-Y. (2017). EFL learning motivation and influence of private education: cross-grade survey results. English Teaching, 72(3), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.72.3.201709.25.

Kim, T.-Y., & Kim, Y. (2019). EFL learning motivation in Korea: historical background and current situation. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 411–428). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_20.

Kim, T.-Y., Kim, Y., & Kim, J.-Y. (2018). A qualitative inquiry on EFL learning demotivation and resilience: a study of primary and secondary EFL students in South Korea. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0365-y.

Kim, Y.-S. (2004). Exploring the role of integrative orientation in Korean EFL environment. English Teaching, 59(3), 77–91.

Komarraju, M., & Nadler, D. (2013). Self-efficacy and academic achievement: why do implicit beliefs, goals, and effort regulation matter? Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.01.005.

Koopman, J., Howe, M., Hollenbeck, J. P., & Sin, H. P. (2015). Small sample mediation testing: misplaced confidence in bootstrapped confidence intervals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036635.

Korean Ministry of Education. (2017). Retrieved from https://moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=316&lev=0&statusYN=C&s=moe&m=0302&opType=N&boardSeq=71805

Lasagabaster, D. (2011). English achievement and student motivation in CLIL and EFL settings. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2010.519030.

Li, P., & Pan, G. (2009). The relationship between motivation and achievement—a survey of the study motivation of English majors in Qingdao Agricultural University. English Language Teaching, 2(1), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v2n1p123.

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308223.

Makarchuk, D. (2005). Integrative motivation and EFL learning in South Korea. The Korea TESOL Journal, 8(1), 1–26.

Masgoret, A.-M., & Gardner, R. C. (2003). Attitudes, motivation, and second language learning: a meta-analysis of studies conducted by Gardner and associates. Language Learning, 53(S1), 167–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00227.

Möller, J., Zitzmann, S., Helm, F., Machts, N., & Wolff, F. (2020). A meta-analysis of relations between achievement and self-concept. Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 376–419. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320919354.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: a meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38.

Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language learning motivation: expanding the theoretical framework. The Modern Language Journal, 78(1), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/329249.

Papi, M., & Abdollahzadeh, E. (2012). Teacher motivational practice, student motivation, and possible L2 selves: an examination in the Iranian EFL context. Language Learning, 62(2), 571–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00632.x.

Pintrich, P. R., & de Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053003024.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Raoofi, S., Tan, B. H., & Chan, S. H. (2012). Self-efficacy in second/foreign language learning contexts. English Language Teaching, 5(11), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n11p60.

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261.

Shim, J., Kim, J., & Park, H. (2012). A study of English learning motivation for Korean high school student in a new town. English21, 25(4), 373–394. https://doi.org/10.35771/engdoi.2012.25.4.017.

Song, B., & Kim, T.-Y. (2016). Teacher (de)motivation from an Activity Theory perspective: cases of two experienced EFL teachers in South Korea. System, 57, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.02.006.

Song, B., & Kim, T.-Y. (2017). The dynamics of demotivation and remotivation among Korean high school EFL students. System, 65, 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.12.010.

StataCorp. (2019). Stata statistical software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC..

Tofighi, D., & Kelley, K. (2019). Indirect effects in sequential mediation models: evaluating methods for hypothesis testing and confidence interval formation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 55(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1618545.

Wang, C., Schwab, G., Fenn, P., & Chang, M. (2013). Self-efficacy and self-regulated learning strategies for English language learners: comparison between Chinese and German college students. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 3(1), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v3n1p173.

Warden, C. A., & Lin, H. J. (2000). Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian EFL setting. Foreign Language Annals, 33(5), 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2000.tb01997.x.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2020). 35 years of research on students’ subjective task values and motivation: a look back and a look forward. In A. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science: Vol. 7 (pp. 162–198). Elsvier.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., & Möller, J. (2020). How dimensional comparisons help to understand linkages between expectancies, values, performance, and choice. Educational Psychology Review, 32(3), 657–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09524-2.

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: the role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312029003663.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2005). Homework practices and academic achievement: the mediating role of self-efficacy and perceived responsibility beliefs. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30(4), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.05.003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.H., Shin, H.W. Second Language Learners’ Self-efficacy and English Achievement: the Mediating Role of Integrative Motivation. English Teaching & Learning 45, 325–338 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-021-00083-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-021-00083-5