Abstract

This work investigated the mechanical properties of epoxy resin composites embedded with graphene oxide (GO) using a novel two-phase extraction method. The graphene oxide from water phase was transferred into epoxy resin forming homogeneous suspension. Hyperbranched polyamine-ester (HBPE) anchored graphene oxide (GOHBPE) was prepared by modifying GO with HBPE using a neutralization reaction. Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed that the HBPE was successfully grafted to the GO surface. The mechanical properties and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) of the composites demonstrated that GOHBPE played a critical role in mechanical reinforcement owing to the layered structure of GO, wrinkled topology, surface roughness and surface area ascending from various oxygen groups of GO itself, and the inarching of HBPE and the reaction among GO, HBPE, and epoxy resin. The transferred GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites showed 69.1% higher impact strength, 129.1% more tensile strength, 45.3% larger modulus, and 70.8% higher strain compared to that of cured neat epoxy resin. The glass transition temperature (Tg) of GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites was increased from 135 to 141 °C and their damping capacity was also improved from 0.71 to 0.91. This study provides guidelines for the fabrication of strengthened polymer composites using phase transfer approach.

ᅟ

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Graphene serves as the basic cell of other carbon materials (such as fullerene, carbon nanotubes, and graphite) and has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years due to its unique physical and chemical properties such as high thermal heat conductivity (5300 W (m K)−1 [1]), mechanical elasticity modulus (1.0 TPa [2]) and large specific surface (2600m2 g−1 [3,4,5]). Owing to these outstanding properties, graphene sheets have been widely applied in different fields such as lithium ion batteries [6,7,8,9], supercapacitors [10,11,12], biomedical materials [13,14,15], and composite materials [16, 17].

However, the weak interactions between pure graphene and other media as well as strong van der Waals forces between graphene sheets make it prone to aggregation and therefore limit its potential application. On the other hand, graphene oxide (GO) platelets have similar structures in two-dimensional space compared to graphene. They also possess chemically reactive functionalities, such as hydroxyl and epoxy groups located on the basal plane and carbonyl and carboxyl groups located mainly at the edge, which can introduce further functionalization of the GO platelets and improve the dispersion and compatibility of GO within the matrix resin. These properties allow for a wider range of applications for graphene and graphite oxide materials [18, 19].

Carboxylic acids have been a key feature in many organic reactions applied to GO. The acid groups can be activated using thionyl chloride, and then a subsequent acylation reaction using propargyl alcohol can be used to obtain the alkynyl GO (GO–C≡CH). The well-defined immobilization of polystyrene (PS) onto GO subsequently takes advantage of click chemistry between the alkyne GO sheets and azido-terminated polystyrene [20]. The poly (styrene-b-ethylene-co-butylene-b-styrene) (SEBS) triblock copolymers can be covalently attached onto GO by taking advantage of a similar click reaction, which incorporates PS into the platelets as the reinforcing fillers. In addition, the epoxy and hydroxyl groups located on the basal plane can be easily modified through ring-opening reactions and esterification. For example, Yang et al. [21] reported functionalized GO platelets via a nucleophilic SN2 displacement reaction between the epoxide and amine groups of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTS) and the covalent incorporation of functionalized GO into silica matrix. In 2011, Yang et al. [22] demonstrated the azide GO via the reaction among 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide, triethylamine, and GO. The azide-functionalized GO and alkynyl PS can be coupled via a Cu catalyzed [3 + 2] Huisgen cycloaddition between the alkyne and azide end groups, yielding polymer-functionalized GO, which exhibits excellent solubility in organic solvents such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), dimethyl formamide (DMF), and trichloromethane (CHCl3). Adjusting the length of the PS chain allows the control over the distance between various layers of GO.

In addition to modifications via covalent grafting, GO can also undergo non-covalent functionalization via π-π stacking or van der Waals interactions. This type of reaction has the added benefits of being relatively simple and also maintaining the original conjugated structure, mechanical properties and electrochemical properties of the GO platelets. However, non-covalent bonds are relatively weak, which makes the grafting density distribution of the molecule on the GO less. For example, Lu et al. [23] reported that GO bonds dye-labeled ssDNA via strong non-covalent interactions between nucleobases and aromatic compounds to obtain DNA sensors, which can be used as platforms for the fast, sensitive, and selective detection of biomolecules.

Polymer composites with GO have attracted great interest due to their unique properties, which are derived from extended interactions between the GO and the matrix and their wide potential applications such as electromagnetic wave shielding and sensors [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. For example, Cao et al. [33] found that the tensile strength and young’s modulus of GO composites increased by 78 and 73%, respectively, when compared with pure polystyrene. The N-doped graphene oxides composited with Co3O4 nanoparticles enhanced activation energy for the low temperature region by 81% compared to pure methylsilicone resin [34]. Yang et al. [21] demonstrated that the compressive failure strength and the toughness of APTS monoliths improved by 19.9 and 92%, respectively, when 0.1 wt% functionalized GO sheets were added. In general, nanofillers are directly dispersed in a resin matrix via thermal exfoliation at high temperature [35,36,37,38] or are dispersed in an organic solvent which is later evaporated [9, 39,40,41], resulting in polymer composites. However, Yang et al. [42] recently described a new economically viable method where GO was dispersed through a two-phase extraction resulting in GO/epoxy resin composites. The compressive failure strength and toughness of composites were drastically improved. In order to improve the dispersion in the matrix and increase their extraction efficiency, we treated GO by hyperbranched polyamine-ester (HBPE) in this work. HBPE with tertiary amine functionalities were grafted onto GO to obtain well dispersed GO in water. The functionalized GO (named as GOHBPE) was then transferred to the epoxy matrix through a two-phase extraction. This green method is different from the traditional hot melt dispersion method and organic solvent based methods while maintaining the structural integrity of the GO during the process. Finally, the GO/epoxy resin composites were prepared by the casting method. DMA measurements, tensile and impact testing were utilized to elucidate the mechanical properties of composites.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

Natural graphite (CP, ignition residue ≤ 0.15%, granularity ≤ 30 μm), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36–38%) and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Potassium permanganate (KMnO4, AR) and sodium nitrate (NaNO3, AR) were purchased from Shanghai Su Yi Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. The epoxy resin E-51 was obtained from Wuxi Blue Star resin factory and was composed of the diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A resin with an average epoxy value Ev = 0.51 mol 100 g−1. Methyltetrahydrophthalic anhydride (MeTHPA) was used as the curing agent and purchased from Pu Yang Huicheng Electronic material Co, Ltd. 2,4,6-Tri(dimethylaminomethyl) phenol (DMP-30) was used as an accelerant and was purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Co. Ltd.

The hyperbranched poly(amine-ester)s (HBPE) was synthesized using pentaerythritol as the core molecules and N,N-diethylol-3-amine methylpropionate as the AB2 branched monomer based on our previous work [43]. Briefly, the N,N-diethylol-3-amine methylpropionate was prepared via Michael addition of methyl acrylate and diethanolamine as the AB2 monomer. Then pentaerythritol, AB2 monomer, and p-toluene sulfonic acid were stirred and processed at 115 °C for 2.5 h. The residual unreacted monomers and by-product methanol were removed to obtain HBPE.

2.2 Synthesis of GO

The GO was obtained by pressurized oxidation [44]. NaNO3, natural graphite and H2SO4 (mass ratio 1:1: 50) were added to a hydrothermal reactor, followed by the slow addition of KMnO4 under ice water. The kettle was then tightened quickly. The hydrothermal reactor was frozen for 2.5 h at 0 °C and then heated for 3 h at 110 °C. After cooling, the kettle was opened and the mixture was poured into deionized water and stirred to dilute the reaction. A proper amount of H2O2 and HCl were then added until the solution turned yellow. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged for 5 min at 8000 rpm. Dialysis of the under layer was deposited for 3 days in a dialysis bag followed by ultrasonic dispersion for 30 min to obtain the dispersion liquid. The dispersion liquid was dried in an oven at 80 °C to obtain GO.

2.3 Preparation of modified GO (GOHBPE)

Hyperbranched polyamine-ester (HBPE, 5 g) and GO (1.0 g) were added to a beaker. The mixture was dispersed using a high shear dispersing emulsifier for 15 min. The suspension was then poured into three separate flasks. An adequate amount of toluene sulfonic acid as the catalyst was added and reacted for 24 h at 60 °C. The products were filtered with a mixed fiber film with 0.22 μm in diameter and rinsed with deionized water. The final solid powder (referred to as GOHBPE) was dried at 80 °C for 24 h before further use.

2.4 Preparation of GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites

A homogenous dispersion of GOHBPE in epoxy resin was obtained using a two-phase extraction. First, 2 g GOHBPE was dispersed in 4 mL deionized water in an ultrasonic bath for 1 h to prepare GOHBPE suspension. Next, 40 g epoxy resin was mixed with a portion of the GOHBPE suspension in three 250-mL flasks. The mixtures were stirred at 50 °C for overnight in order to completely remove water resulting in a homogenous mixture. The contents of GOHBPE were 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 wt%.

The mixtures were degassed at 90 °C for 10 min to remove bubbles before adding hardener. The hardener and accelerant were then added to the mixture at ambient temperature and the mixture was quickly poured into a preheated steel mold (epoxy resin/hardener/accelerant (weight ratio) = 100:75:1). The mold was heated at 80 °C for 1 h, 140 °C for 3 h, and 180 °C for 3 h. After curing, the samples were cooled in the stove and were incised using standard procedures.

2.5 Characterization

The surface functional groups were characterized with a Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Digilab FTS3000). X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out using a XRD-6000 diffractometer with CuKa radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on ultra thin films using a JEM-2100 instrument and an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. A few drops of aqueous sample were placed on a copper grid and dried for the TEM measurement. Raman spectroscopy was carried out at room temperature using a Renishaw InviaReflex spectrometer equipped with a 532-nm semiconductor laser. All the samples were powders, which were deposited directly on the quartz substrate.

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was performed using a DMAQ800 dynamic analyzer and a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The samples were heated from 25 to 200 °C using 5 °C min−1 rate at 1 Hz frequency. The mechanical properties of the GO/epoxy composites were tested on the universal testing machine (CMT-5105) according to GB/T 2567–2008. A crosshead speed of 5 mm/min*** was used.. Ten specimens of each composite were tested and the mean values of the mechanical properties were reported. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) examinations were completed using a JMS–6480 at 5.0 kV. The SEM samples were coated with gold to make them conducting.

3 Results and discussion

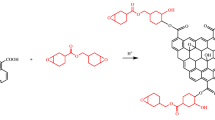

Surface-active functional groups such as hydroxyl and epoxy groups located on the basal plane of GO, and carbonyl and carboxyl groups mainly at the edge of GO can participate in chemical reactions with other function groups. Scheme 1 shows the functionalization process of GO by HBPE. The carboxyl groups at the edge of GO and the hydroxyl groups on HBPE undergo an esterification in the presence of catalyst resulting in the covalent anchoring the polymer onto the surface of GO.

The chemical structures of GO and GOHBPE can be probed using FTIR spectra (Fig. 1). A broad absorption at 3414 cm−1 can be seen (Fig. 1a), and is attributed to the stretching of hydroxyl groups for GO. The band at 1651 cm−1 is corresponding to the carboxyl C=O stretching vibration and the band at 1195 cm−1 can be assigned to the C–O stretching. A weak absorption at about 900 cm−1 corresponds to the epoxide groups [45]. The spectrum of GO that has been treated with HBPE shows a broad and strong absorption peak at 3381 cm−1 resulting from the stretching vibration of -OH and -NH bonds. A peak at 1589 cm−1 is also observed and can be attributed to the bending vibration of the -NH bonds in HBPE. The absorption peak at 1406 cm−1 is representative of the carboxyl C–O vibration. The C–N stretching vibration is also observed at 1072 cm−1. The FTIR results confirmed that the HBPE had been successfully grafted onto the GO surface.

Figure 2 shows the Raman spectra of GO and GOHBPE. In the Raman spectrum of pristine GO, a broad D band at 1342 cm−1 and a G band at 1577 cm−1 are observed, due to the C–C disordered vibrations of the sp3-bonded carbon atoms and the C–C stretching vibrations of the sp2-bonded carbon atoms, respectively. The I D/I G ratio is 0.92. The Raman spectrum of the GOHBPE also contains D and G peaks with an I D/I G of 0.98. The GOHBPE exhibits a similar peak shape and position suggesting that the decoration of HBPE does not destroy the structure of GO. The increasing I D/I G indicates that the reaction between GO and HBPE resulted in new defects.

XRD is a useful instrument for characterizing the structural quality of GO-based materials. As shown in Fig. 3, the XRD pattern of GO exhibits a typical diffraction peak at 11.56°, corresponding to an interlayer spacing of 0.76 nm. However, this peak does not appear in the pattern for the GOHBPE sample, indicating that the HBPE is successfully grafted on the surface of GO and decreases the order degree of GO.

TEM was also used to investigate the morphology and microstructure of the GO and GOHBPE. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, the GO sheets exhibit a folded and wrinkled structure for stable two-dimensional structure. In contrast, the TEM image of GOHBPE shows the GO sheet becomes blurring as if it is covered with a voile. When compared with GO, the surface of the GOHBPE sheets is rough and has lower transparency (Fig. 4c, d), indicating that the HBPE causes the thickness increase of GO. The wrinkles and surface roughness can improve the compatibility and interfacial adhesion between GO and the epoxy resin, similar to epoxy nanocomposites with the graphene decorated with protruding nanoparticles [46]. In addition, the hydroxyl and amine groups of HBPE can further react with the epoxy resin, resulting in an enhanced mechanical interlocking mechanism for the epoxy resin composites.

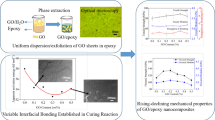

The above results demonstrate that GOHBPE has been successfully prepared. Then the GOHBPE was ultrasonically treated in water to create a homogenous yellow-brown transparent dispersion and mixed with epoxy resin (see Fig. 5). In this work, 0.2 g mL−1 dispersion was used to reduce the usage of water in the follow-up experiment. From Fig. 5, we can see water and epoxy resin are incompatible having obvious layering. However, the GOHBPE can be successfully and homogeneously transferred into an epoxy resin from GOHBPE dispersion with stirring through a two-phase extraction. The epoxy resin suspension containing uniform GO was achieved after removing the water (see Fig. 5). Then the anhydride curing agent and accelerant were added into this uniform suspension and undergone the solidification process to form GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites.

The impact and tensile tests were carried out to investigate how the transferred GOHBPE impact on the mechanical properties of the epoxy matrix. When mixed with GOHBPE, the impact strength of epoxy resin composites is higher than that of the pure epoxy resin (see Fig. 6a), indicating that GOHBPE can significantly improve the toughness of epoxy resin. With increasing the GOHBPE weight fraction, the impact strength first increases and then decreases, indicating an optimal concentration of GOHBPE. When the weight fraction of GOHBPE is 0.2 wt%, the impact strength rises to the highest value 15.9 KJ m−2 with an increase of 69.1% compared to the pure epoxy resin (9.4 KJ m−2). The impact strength of GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites decreases when the weight fraction of GOHBPE continues to increase, probably because the dispersibility of GOHBPE in the epoxy resin decreases and a concentrated stress appears. Figure 6b, c shows the effects of GOHBPE on the tensile properties of epoxy resin composites.

The test results revealed that stress-strain curves of the addition of GOHBPE and pure epoxy resin exhibit a similar tendency, as shown in Fig. 6b. All samples broke immediately after the stress reached the maximum value. In the whole tensile curves, no yield points appear for any sample attributed to the brittle fracture of epoxy resin. It is notable that the stress-strain curve reveals a strong nonlinear feature different from the description in ref. [47], which illustrate the elastic module decreasing first and then rising continuously until the sample was fractured. As we know, the modulus (E) is the ratio of stress and strain in the low strain region, namely, the tensile modulus decreases first and then increases in the tensile process. Figure 6c illustrates the stress-strain curve and the calculated value for neat epoxy resin. “A” region on curve in Fig. 6c displays the modulus decreasing from 473 to 295 MPa for a short period of time because the macromolecular disentanglement of epoxy resin in a small space leads to the lower stress induced deformation. B region reveals the modulus increasing from 295 to 826 MPa. For brevity, enhancing orientation degree under tensile force causes the rising intermolecular force which results in the ability of resisting deformation. The modulus of neat epoxy resin reaches its highest (826 MPa) at tensile strength (12 MPa).

The tensile strengths, moduli, and strains of the pure epoxy and its composites are shown in Table 1. With increasing the GOHBPE weight fraction, the tensile strength first increases and then decreases, similar to the tendency of impact strength as observed. The composites at 0.2% GOHBPE show a remarkable increase in the tensile strength, modulus and strain by 129.1, 45.3 and 70.8%, respectively. The remarkable improvement for the mechanical properties of epoxy resin at extraordinarily low content of GOHBPE can be attributed to three main reasons. First, GO itself possesses the layered structure. Carbon bonding within layers is very strong but interlayer bonding is much weaker. When GO is processed to epoxy resin and the interlayer bonds are stretched, and then the high strength, modulus and strain are found. Second, the distortions and defects coming from various oxygen groups of GO itself and the inarching of HBPE lead to a wrinkled topology, increased surface roughness and larger surface area which can improve the compatibility and interfacial adhesion between GO and the epoxy resin [48, 49]. In addition, the hydroxyl and amine groups of HBPE can further react with the epoxy resin, resulting in an enhanced mechanical interlocking mechanism for the epoxy resin composites, similar phenomena have been observed in polyester composites with the carbon fibers interfaced with POSS [50, 51]. When the weight fraction of GOHBPE is 0.5 and 1%, the tensile properties of GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites are not significantly improved. This is most likely because when the content is too low, it is unable to affect the bending strength of the material and when the content is too high, it is unable to be homogeneously dispersed in the epoxy resin matrix.

The impact fracture morphologies of pure epoxy resin and GOHBPE/epoxy resin composites are shown in Fig. 7. A relatively smooth surface with river-like patterns is seen in the case of the pure resin (Fig. 7a, b), indicating a brittle fracture [52]. Figure 7c, d shows the impact fracture morphologies of modified GO/epoxy resin composites, which exhibit a rough surface and dimple patterns. Due to the increased toughness of epoxy resin composites resulting from the flexibility of GO and HBPE, the resistance of the material to crack propagation is large and leads to a more ductile fracture pattern. Thus, GOHBPE addition enhances the strength and toughness of the composites, which is consistent with the results of mechanical tests.

Dynamic mechanical properties were measured in order to study the effects of GOHBPE content on the rigidity and damping properties of epoxy resin composites. As shown in Fig. 8a, the storage modulus of neat epoxy and its composites decreases with increasing the temperature. The addition of GOHBPE to the epoxy resin raises the storage modulus, implying an increase in the rigidity and the improvement of resisting to the external load and deformation over the temperature range when the GOHBPE content is 0.1 and 0.5 wt% due to better adhesion between GOHBPE and the polymer matrix. It can be seen that the glass transition temperature (T g) moves to a higher temperature as GOHBPE limits the movement of molecular chain segments from Fig. 8b. This is in contrast to our previous report where the T g moves to lower temperatures [38]. As GO sheets contain many reactive epoxide groups, the hydroxyl and amine groups of HBPE at the edge of GO may undergo a further reaction with the epoxy resin leading to GOHBPE being well dispersed and embedded into the epoxy resin matrix, resulting in a higher T g.

The loss factor (tan θ) is usually used to evaluate the damping property of materials [53,54,55,56]. The temperature at which the loss factor curve reaches a maximum is often recorded as the T g. It can be seen from Fig. 8c that the T g of pure epoxy resin, according to this measurement, is 135 °C with a loss factor of 0.71. The T g and the loss factor both increase reaching a maximum of 141 °C and 0.91, respectively, when the GOHBPE content is 0.2 wt%. This indicates that while increasing the toughness of the epoxy resin, GOHBPE can also improve its damping properties. In the mixture, the curing agents not only solidify the epoxy resin but also react with the GO sheets through the epoxide and amine groups. Simultaneously, hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of GO and the epoxy resin, amine groups of HBPE and the epoxy resin also may participate in the chemical reactions. In short, GOHBPE is embedded in the epoxy resin via covalent bonding, resulting in a stronger interface and increased cross linking, and higher T g. Moreover, the flexibility of the GO ameliorates the damping properties of the composites.

4 Conclusion

The HBPEs were successfully grafted on GO via covalent bonding forming a stable suspension in water. The GOHBPE was homogeneously transferred into epoxy resin matrix from water using a two-phase extraction. In addition, GOHBPE was found to improve the mechanical properties, heat stability, and damping properties of the epoxy resin matrix owing to the strong interfacial bonding strength, covalent cross-linking, and 2-D GO structure. The tensile strength, the modulus, and the strain had been improved by 129.1, 45.3, and 70.8%, respectively at 0.2% transferred GOHBPE sheets. At the same fraction, the highest impact strength was 15.9 KJ m−2 and had been improved by 69.1%. Their T g and loss factor were increased from 135 °C and 0.71 to 141 °C and 0.91, respectively. This method may have broader applications in the future for graphene and other polymer matrix composites.

References

Balandin AA, Ghosh S, Bao W, Calizo I, Teweldebrhan D, Miao F, Lau CN (2008) Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett 8(3):902–907

Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J (2008) Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321(5887):385–388

Nair RR, Blake P, Grigorenko AN, Novoselov KS, Booth TJ, Stauber T, Peres NMR, Geim AK (2008) Fine structure constant defines visual transparency of graphene. Science 320(5881):1308

Stauber T, Peres NMR, Geim AK (2008) Optical conductivity of graphene in the visible region of the spectrum. Phys Rev B 78(8):1–8

Geim AK (2009) Graphene: status and prospects. Science 324(5934):1530–1534

Shen W, Wang Y, Yan J, Wu H, Guo S (2015) Enhanced electrochemical performance of lithium iron(II) phosphate modified cooperatively via chemically reduced graphene oxide and polyaniline. Electrochimi Acta 173:310–315

Sun Y, Hu X, Luo W, Xia F, Huang Y (2013) Reconstruction of conformal nanoscale MnO on graphene as a high-capacity and long-life anode material for lithium ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater 23(19):2436–2444

Bonaccorso F, Colombo L, Yu G, Stoller M, Tozzini V, Ferrari AC, Ruoff RS, Pellegrini V (2015) Graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems for energy conversion and storage. Science. 347(6217):1246501

Wei W, Yang S, Zhou H, Lieberwirth I, Feng X, Muellen K (2013) 3D graphene foams cross-linked with pre-encapsulated Fe3O4 nanospheres for enhanced lithium storage. Adv Mater 25(21):2909–2914

Li G, Xu C (2015) Hydrothermal synthesis of 3D NixCo1-xS2 particles/graphene composite hydrogels for high performance supercapacitors. Carbon 90:44–52

Lee JW, Hall AS, Kim J-D, Mallouk TE (2012) A facile and template-free hydrothermal synthesis of Mn3O4 nanorods on graphene sheets for supercapacitor electrodes with long cycle stability. Chem Mater 24(6):1158–1164

Liu L, Niu Z, Zhang L, Zhou W, Chen X, Xie S (2014) Nanostructured graphene composite papers for highly flexible and foldable supercapacitors. Adv Mater 26(28):4855–4862

Hu W, Peng C, Lv M, Li X, Zhang Y, Chen N, Fan C, Huang Q (2011) Protein corona-mediated mitigation of cytotoxicity of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 5(5):3693–3700

Liao K-H, Lin Y-S, Macosko CW, Haynes CL (2011) Cytotoxicity of graphene oxide and graphene in human erythrocytes and skin fibroblasts. ACS Appl Mater Inte 3(7):2607–2615

Zhang X, Yin J, Peng C, Hu W, Zhu Z, Li W, Fan C, Huang Q (2011) Distribution and biocompatibility studies of graphene oxide in mice after intravenous administration. Carbon 49(3):986–995

Kim H, Abdala AA, Macosko CW (2010) Graphene/polymer nanocomposites. Macromolecules 43(16):6515–6530

Ramanathan T, Abdala AA, Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Herrera-Alonso M, Piner RD, Adamson DH, Schniepp HC, Chen X, Ruoff RS, Nguyen ST, Aksay IA, Prud'Homme RK, Brinson LC (2008) Functionalized graphene sheets for polymer nanocomposites. Nat Nanotechnol 3(6):327–331

Dreyer DR, Park S, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS (2010) The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem Soc Rev 39(1):228–240

Novoselov KS, Fal'ko VI, Colombo L, Gellert PR, Schwab MG, Kim K (2012) A roadmap for graphene. Nature 490(7419):192–200

Sun S, Cao Y, Feng J, Wu P (2010) Click chemistry as a route for the immobilization of well-defined polystyrene onto graphene sheets. J Mater Chem 20(27):5605–5607

Yang H, Li F, Shan C, Han D, Zhang Q, Niu L, Ivaska A (2009) Covalent functionalization of chemically converted graphene sheets via silane and its reinforcement. J Mater Chem 19(26):4632–4638

Yang X, Ma L, Wang S, Li Y, Tu Y, Zhu X (2011) “Clicking” graphite oxide sheets with well-defined polystyrenes: a new strategy to control the layer thickness. Polymer 52(14):3046–3052

Lu CH, Yang HH, Zhu CL, Chen X, Chen GN (2009) A graphene platform for sensing biomolecules. Angew Chem Int Edt 48(26):4785–4787

Gu J, Liang C, Zhao X, Gan B, Qiu H, Guo Y, Yang X, Zhang Q, Wang DY (2017) Highly thermally conductive flame-retardant epoxy nanocomposites with reduced ignitability and excellent electrical conductivities. Compos Sci Technol 139:83–89

Li Y, Zhu J, Wei S, Ryu J, Sun L, Guo Z (2011) Poly(propylene)/graphene nanoplatelet nanocomposites: melt rheological behavior and thermal, electrical, and electronic properties. Macromol Chem and Phys 212(18):1951–1959

Zhu J, Wei S, Haldolaarachchige N, He J, Young DP, Guo Z (2012) Very large magnetoresistive graphene disk with negative permittivity. Nanoscale 4(1):152–156

Zhu J, Wei S, Gu H, Rapole SB, Wang Q, Luo Z, Haldolaarachchige N, Young DP, Guo Z (2012) One-pot synthesis of magnetic graphene nanocomposites decorated with core@double-shell nanoparticles for fast chromium removal. Environ Sci Technol 46(2):977–985

Zhu J, Sadu R, Wei S, Chen DH, Haldolaarachchige N, Luo Z, Gomes JA, Young DP, Guo Z (2012) Magnetic graphene nanoplatelet composites toward arsenic removal. ECS J Solid State SC 1(1):M1–M5

Zhu J, Chen M, Qu H, Zhang X, Wei H, Luo Z, Colorado HA, Wei S, Guo Z (2012) Interfacial polymerized polyaniline/graphite oxide nanocomposites toward electrochemical energy storage. Polymer 53(25):5953–5964

Liu H, Li Y, Dai K, Zheng G, Liu C, Shen C, Yan X, Guo J, Guo Z (2016) Electrically conductive thermoplastic elastomer nanocomposites at ultralow graphene loading levels for strain sensor applications. J Mater Chem C 4(1):157–166

Liu H, Huang W, Yang X, Dai K, Zheng G, Liu C, Shen C, Yan X, Guo J, Guo Z (2016) Organic vapor sensing behaviors of conductive thermoplastic polyurethane-graphene nanocomposites. J Mater Chem C 4(20):4459–4469

Gu H, Ma C, Gu J, Guo J, Yan X, Huang J, Zhang Q, Guo Z (2016) An overview of multifunctional epoxy nanocomposites. J Mater Chem C 4(48):5890–5906

Cao Y, Lai Z, Feng J, Wu P (2011) Graphene oxide sheets covalently functionalized with block copolymers via click chemistry as reinforcing fillers. J Mater Chem 21(25):9271–9278

Jiang B, Zhao LW, Guo J, Yan XR, Ding DW, Zhu CC, Huang YD, Guo ZH (2016) Improved thermal stability of methylsilicone resins by compositing with N-doped graphene oxide/Co3O4 nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res 18(6):1–11

Li P, Zheng Y, Yang R, Fan W, Wang N, Zhang A (2015) Flexible nanoscale thread of MnSn(OH)6 crystallite with liquid-like behavior and its application in nanocomposites. ChemPhysChem 16:2524–2529

Lan L, Zheng YP, Zhang AB, Zhang JX, Wang N (2012) Study of ionic solvent-free carbon nanotube nanofluids and its composites with epoxy matrix. J Nanopart Res 14(3):1–10

Verdejo R, Barroso-Bujans F, Rodriguez-Perez MA, de Saja JA, Lopez-Manchado MA (2008) Functionalized graphene sheet filled silicone foam nanocomposites. J Mater Chem 18:2221–2226

Tang J, Zhou H, Liang Y, Shi X, Yang X, Zhang J (2014) Properties of graphene oxide/epoxy resin composites. J Nanomater 696859

Shen XJ, Pei XQ, Fu SY, Friedrich K (2013) Significantly modified tribological performance of epoxy nanocomposites at very low graphene oxide content. Polymer 54(3):1234–1242

Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Dommett GHB, Kohlhaas KM, Zimney EJ, Stach EA, Piner RD, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS (2006) Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442(7100):282–286

Yang L, Wang ZQ, Ji YC, Wang JN, Xue G (2014) Highly ordered 3D graphene-based polymer composite materials fabricated by “particle-constructing” method and their outstanding conductivity. Macromolecules 47(5):1749–1756

Yang H, Shan C, Li F, Zhang Q, Han D, Niu L (2009) Convenient preparation of tunably loaded chemically converted graphene oxide/epoxy resin nanocomposites from graphene oxide sheets through two-phase extraction. J Mater Chem 19(46):8856–8860

Zheng YP, Zhang JX, Yang YD, Lan L (2013) The synthesis of hyperbranched poly (amine-ester) and study on the properties of its UV-curing film. J Adhes Sci Technol 27(24):2666–2775

Bao C, Song L, Xing W, Yuan B, Wilkie CA, Huang J, Guo Y, Hu Y (2012) Preparation of graphene by pressurized oxidation and multiplex reduction and its polymer nanocomposites by masterbatch-based melt blending. J Mater Chem 22:6088–6096

Gu H, Zhang H, Ma C, Lyu S, Yao F, Liang C, Yang X, Guo J, Guo Z, Gu J (2017) Polyaniline assisted uniform dispersion for magnetic ultrafine barium ferrite nanorods reinforced epoxy metacomposites with tailorable negative permittivity. J Phys Chem C 121(24):13265–13273

Zhang X, Alloul O, He Q, Zhu J, Verde MJ, Li Y, Wei S, Guo Z (2013) Strengthened magnetic epoxy nanocomposites with protruding nanoparticles on the graphene nanosheets. Polymer 54(14):3594–3604

Lee Y (2017) Mechanical properties of epoxy composites reinforced with ammonia-treated graphene oxides. Carbon Lett 21:1–7

Song P, Cao Z, Cai Y, Zhao L, Fang Z, Fu S (2011) Fabrication of exfoliated graphene-based polypropylene nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical and thermal properties. Polymer 52(18):4001–4010

Gu H, Ma C, Liang C, Meng X, Gu J, Guo Z (2017) Low loading of grafted thermoplastic polystyrene strengthened and toughened transparent epoxy composites. J Mater Chem C 5(17):4275–4285

Jiang D, Xing L, Liu L, Sun S, Zhang Q, Wu Z, Yan X, Guo J, Huang Y, Guo Z (2015) Enhanced mechanical properties and anti-hydrothermal ageing behaviors of unsaturated polyester composites by carbon fibers interfaced with POSS. Compos Sci Technol 117:168–175

Jiang D, Xing L, Liu L, Yan X, Guo J, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Wu Z, Zhao F, Huang Y, Wei S, Guo Z (2014) Interfacially reinforced unsaturated polyester composites by chemically grafting different functional POSS onto carbon fibers. J Mater Chem A 2(43):18293–18303

Guo ZH, Pereira T, Choi O, Wang Y, Hahn HT (2006) Surface functionalized alumina nanoparticle filled polymeric nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties. J Mater Chem 16(27):2800–2808

Chen X, Wei S, Yadav A, Patil R, Zhu J, Ximenes R, Sun L, Guo Z (2011) Poly(propylene)/carbon nanofiber nanocomposites: ex situ solvent-assisted preparation and analysis of electrical and electronic properties. Macromol Mater Eng 296(5):434–443

Bafana AP, Yan X, Wei X, Patel M, Guo Z, Wei S, Wujcik EK (2017) Polypropylene nanocomposites reinforced with low weight percent graphene nanoplatelets. Compos Part B-Eng 109:101–107

Lu N, Oza S (2015) A comparative study of the mechanical properties of hemp fiber with virgin and recycled high denisty polyethylene matrix. Composites Part B- Eng 45(1):1651–1656

Lu N, Oza S, Ferguson I (2012) Effect of alkali and silane treatment on the therma stability of hemp fiber as reinforcement in composite structures. Adv Mater Res 415:666–670

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the supports from the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institution; the Key Laboratory Funded by Jiangsu advanced welding technology, National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51402132), Jiangsu Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. BK2012279 and No. BK20140505), and US National Science Foundation under grants of CMMI-1560834 and IIP-1700628.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, JX., Liang, YX., Wang, X. et al. Strengthened epoxy resin with hyperbranched polyamine-ester anchored graphene oxide via novel phase transfer approach. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 1, 300–309 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-017-0007-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-017-0007-0