Abstract

Box-Behnken design was utilized to obtain optimized process condition for maximizing lactic acid extraction efficiency and initial extraction rate by emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) process. A mixture of tri-n-octylamine and tri-n-decylamine (1:1, v/v) was employed as carrier in membrane phase of ELM for synergic facilitated lactic acid transport. The effect of different process parameters like lactic acid concentration in feed, sodium carbonate concentration in internal phase, carrier fraction, treatment ratio, phase ratio, stirring speed and contact time has been investigated. Extraction efficiency of 98.5% and 9.36 × 10−9 mol/cm2.sec, initial extraction rate were found under optimized conditions of process parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Lactic acid, a naturally occurring organic acid has versatile applications in various industries such as brewing, food, cosmetic, pharmaceutical industries and as a chemical feed stock etc. (Pimtong et al. 2017; John et al. 2007). Recently, the utilization of L-lactic acid to produce polylactic acid (PLA), a biodegradable polymer and green solvent like lactate esters has led a remarkable increase in its worldwide demand year by year (Pimtong et al. 2017). PLA has given a breather to the worldwide environmental problems associated with the waste plastics disposal with its expected production capacity of 3 million tonne in 2020 (John et al. 2007; Venus et al. 2018).

Chemical synthesis and fermentation are the two routes for the LA production. The biotechnological production of lactic acid has drawn a significant interest of researchers from both environmental and economic viewpoint. The two key stages for lactic acid production are fermentation and product recuperation. Among the two, the product recovery poses the biggest challenge (Li and Shahbazi 2006). The separation, purification and preconcentration of lactic acid produced biotechnologically are comparatively arduous tasks due to its chemical behavior. Its separation by distillation or solvent extraction process is difficult due to low volatility and its strong affinity towards water. The low activity of LA molecules towards water makes conventional extraction techniques unprofitable. Moreover, the urgent need for environmental sustainability and rapidly rising costs have underscored the requirement of novel alternative and effective energy efficient separation and recovery of fermentation products like organic acids and biochemicals of industrial importance.

An emerging and attractive novel separation technique involving emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) proposed by Li in 1968 has shown a considerable potential alternatives to the expensive conventional method for separating the metal ions, pollutants from waste streams and biochemical products with low concentrations (Hachemaoui and Belhamel 2017). ELM is a simplified extraction process (water-in-oil-in-water (w/o/w) emulsion system) with high extraction efficiency where in the primary water-in-oil (w/o) emulsion constituting of the internal and the membrane (organic) phase stabilized by the surfactant (responsible for reduction in free energy) is dispersed in the external feed phase (e.g. fermentation broth or aqueous phase containing solute/ions) (Ahmad et al. 2017; Hong et al. 2017). The solute transport during the ELM process from external phase to the internal phase across the membrane phase occurs due to the combined effect of extraction and stripping unit operations (Ahmad et al. 2017). Selectivity based on the difference in the permeation rate across the membrane phase of individual species present in feed phase is the key criteria for the mass transfer of targeted solute. Addition of carrier such as long chain tertiary amines, organophosphinic acids, phosphine oxides etc. in the membrane phase can further enhance the solute transportation rate by forming a solute-carrier complex selectively in the membrane phase (Berrios et al. 2010). Choosing a suitable carrier along with other operational conditions is one of the key factors that control the extraction efficiency (Garcia et al. 2013). The extraction efficiency can be further immproved by utilizing a mixture of long chain tertiary amines as compared to pure tertiary amine (Uslu et al. 2009). ELM has an advantage of having a high surface area per unit volume (1000–3000 m2/m3) as well as high internal surface area per unit volume (typically 106 m2/m3) resulting in very high mass rates with a considerably smaller working volumes of solvents requirement in comparison to conventional solvent extraction technique (Chanukya and Rastogi 2013; Rajasimman and Karthic 2010) and feasibility of economic continuous operation.

The LA extraction from aqueous phase and fermentation broths using the ELM technique has been studied by various researchers (Uslu et al. 2009; Hong and Hong 1999; Yankov et al. 2004; Gao et al. 2009; Garavand et al. 2017; Kyuchoukov et al. 2001). Although these works showed that ELM is efficient in removal of lactic acid from aqueous phase/fermentation broth, yet very few investigations have been reported on the comprehensive and detailed study on the interactive effect of process variables on response. A number of process parameters like carrier concentration, solute concentration in external phase, stripping reagent concentration in internal phase, treat ratio, internal to membrane phase ratio, surfactant concentration etc. may influence the LA extraction by ELM process from aqueous solution. Hence an effective suitable experimental technique has to be applied to investigate the effect of various process parameters, their interactive effect and to find optimized value of these process paramenters for maximizing the LA extraction by ELM with minimum number of experiments (Yetilmezsoy et al. 2009; Goyal et al. 2011).

The conventional method for process parameters optimization is time consuming since it involves changing one independent variable while keeping all others unchanged at a fixed level. Moreover, it does not provide any information regarding combined effect of all the factors tested and does not often assured determination of optimum conditions. Response surface methodology (RSM) has been widely studied by many investigators for the design of experiments and optimization of process variables. It has been proven to be effective in substantially decreasing the experimental runs without affecting the interactions among the process parameters (Peng et al. 2012). Different types of RSM designs include 3-level factorial design, central composite rotatable design (CCRD), Box-Behnken design (BBD), and D-optimal design. Among them CCRD and BBD are very useful (Chanukya and Rastogi 2013). Fewer experiments are needed with BBD and are less expensive to run in comparison to CCRD with the same number of factors (Babu et al. 2011).

The optimization of extraction efficiency of lactic acid by ELM from aqueous solution using response surface methodology (RSM) is scarce in the literature. Moreover no systematic investigation so far has been reported in the literature for optimization of LA initial extraction rate by ELM using RSM. Keeping in view the above, response surface methodology using BBD (a three-level factorial designs) has been utilized in this work for designing and analysis of experimental and parametric optimization of the initial lactic acid extraction rate and extraction efficiency of lactic acid from aqueous phase in a batch reactor using mixed tertiary amines consisting of trioctylamine (TOA) and tridecylamine (TDA).

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Sorbitanmonooleate (Span 80), trioctylamine,(TOA), sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid were the products of Merck, Germany. Tridecylamine (TDA) was a product of Sigma-aldrich. A commercial n-hexane was procured from Merk Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Lactic acid was the product of HiMedia Lab Pvt.,Mumbai. Na2CO3, copper sulphate (CuSO4.7H2O) and p-phenyl phenol were received from the manufacturer M/s. Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. All the chemicals were of AR grade.

2.2 Experimental Design

The experiments were conducted for investigating the initial LA extraction rate and LA extraction efficiency in accordance with sets of experimental design obtained using Design-Expert 7.16 software (Statease Inc., Minneapolis, USA,) for Box-Behnken design (BBD) with seven variables at three levels each. The effect of lactic acid concentration in feed phase (cl), [M], sodium carbonate concentration in internal phase (cs) [M], carrier fraction in n-hexane (φ, % v/v), treatment ratio (ψ, v/v), phase ratio (Φ, v/v), stirring speed (ω, rpm), on the initial extraction rate (ξ0) and extraction efficiency (ηext) (whereas contact time (τ, min), was additional 7th variable, for the extraction efficiency) were investigated for the ranges as shown in Table 1. A total 62 experiments (Table 2) with various combinations process variables were conducted randomly in triplicate and average value was taken for statistical analysis.

2.3 Membrane Preparation

The membrane phase initially utilized for obtaining the ELM, (w/o/w) was consisted of 3–5% (v/v) Span 80 as stabilizer and 0–8% (v/v) of 1:1(v/v) mixture of tri-n-octylamine, and tri-n-decylamine as carrier in n-hexane which were stirred at constant speed (200 rpm) for 2 min. To this homogeneous membrane phase, 0.025–0.25 [M] stripping phase (Na2CO3 solution) was added drop wise slowly and simultaneously agitated (2000 rpm) at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 20 min using a four blade impeller stirrer (Model: IKA RW 20; Cole-Parmer, India) while maintaining the desired phase (internal phase to organic phase volume) ratio (0.25–0.75 v/v) to obtain a stable ELM. Afterwards the emulsion thus obtained was washed with excess deionized water before transferring to settler to check its stability. On performing the experimental investigation, an emulsion constituted of 4% (v/v) Span 80 in n-hexane (χ), 0.25–0.75 (v/v) phase ratio (Φ), 0–8% (%,v/v) of 1:1(v/v) mixture of tri-n-octylamine, and tri-n-decylamine as carrier in n-hexane (φ), and 0.025–0.25 [M] stripping phase concentration (cs, Na2CO3 solution) stirred at 2000 rpm were very stable.

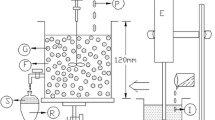

2.4 Lactic Acid Extraction

The extraction experiments was conducted batch-wise in a batch extractor at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) containing freshly prepared ELM (100 ml) to which aqueous lactic acid (external phase) according to desired treatment ratio was added and stirred with the help of agitator as per the experimental design (Table 2). During the preparation of primary emulsion (w/o) of desired phase ratio, the organic phase volume was kept constant and the stripping phase volume was varied. Samples at different time intervals from the external feed phase during extraction process were drawn and analyzed for lactic acid concentration. While for initial extraction rate, (ξ0), the samples were also drawn for analysis LA concentration in feed phase at contact times of 10, 20, 30 and 45 s in addition to desired contact times for each experiment as per experimental design (Table 2). After completion of extraction process, the emulsion and feed phases were separated by gravity settling and their respective volumes were measured.

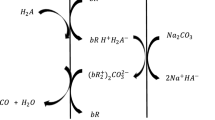

2.4.1 Mass Transfer Mechanism

The schematic representation for the mass transfer of LA is shown in Fig. 1.

2.5 Statistical Analysis and Optimization

During the statistical analysis, at first, the regression equation is fitted to the experimental data for responses. The coefficients of the response model, their standard errors and significance are determined by regression analysis. The process behavior was represented and explained by the quadratic equation:

Where predicted response i.e. initial extraction rate/extraction efficiency is represented by Y, b0, bi, bii and bij represents offset term, linear effect, squared effect and interaction effect, respectively. xi is ith independent variable (Yu et al. 2008) and ε is the random error. The transformation for coding the natural (uncoded) independent variables (X1, X2,.. .,Xk) while developing Eq. (1) has been utilized as

Where xi, Xi, Xi0and ∆Xi are dimensionless coded value, uncoded value, uncoded value at center point and the step change value for the ith independent variable respectively (Yetilmezsoy et al. 2009). After building the regression models, tests were performed for fitting of the models. The optimum values for process variables (within the experimental range) for maximizing initial extraction rate (ξ0) and extraction efficiency (ηext) were determined.

2.6 Analytical Method

Lactic acid concentration was determined thorough colorimetric method (Kimberley and Taylor 1996) by using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (model DR 5000 HACH, USA). The stability analysis of emulsion was confirmed by the pH method ((Jiao et al. 2013) by measuring the pH of the aqueous solutions at different contact times of aqueous phase with emulsion using Eutech pH 5+, pH meter.

2.7 Mathematical Calculations

2.7.1 Calculation for Lactic Acid Extraction

The extraction efficiency had been calculated without considering any emulsion breakage and swelling using the equation:

Where Cl0 and Clτ is the lactic acid concentration in feed phase initially at time t = 0, and at desired contact time as per design of experiment, (Table 2) respectively.

2.7.2 Calculation of Initial Lactic Acid Extraction Rate

During the preliminary experimentation, it has also been observed that lactic acid extraction is favored at the beginning of the experiment. The LA initial extraction rate, ξ0 was determined as:

Where VF and A are the feed volume and interfacial area, respectively, (dE/dt) represents initial rate of change in LA extraction (≤ 20s) and initial extraction rate is expressed in [mol cm−2 s−1] (Basualto et al. 2006). The Souter mean diameter (d) in mm for calculating the emulsion area of interface was calculated using the correlation as described by S. Datta et al. (2003).

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Regression Model

The quadratic models for the initial extraction rate (ξ0) and extraction efficiency (ηext) (in terms of coded forms) after the regression analyses were obtained explaining the role of each variable and their quadratic interaction:

Where X1- lactic acid concentration, X2- sodium carbonate concentration, X3-fraction of carrier in n-hexane, X4- treatment ratio, X5-phase ratio, X6 - stirring speed and X7- contact time.

The significance and models fittings (Eq. 6 & 7) were verified by ANOVA (analysis of variance). ANOVA results for initial extraction rate (ξ0) and extraction efficiency (ηext) are illustrated in Tables 3 and 4 respectively. The fishers variance ratio f value is a measure of data variation about the mean. The significant terms were considered as having p (probability) > f values <0.05 are (Tables 3 and 4). Smaller the magnitude of p > f values, the more significant is the correlation with the corresponding coefficient.

The R2 values were satisfactory (>0.97) for both the responses (p ≤ 0.05) indicating a good agreement between experimentally observed and predicted values. The “Lack of Fit f-value” of 2.12 for ξ0 and 1.73 for ηext implies that it is not significantly relative to the pure error and signifies towards the model best fit (Yu et al. 2008). For ξ0 and ηext, the difference between adjusted R2 and predicted R2 is 0.0127 and 0.0147 respectively, confirming that models are in good agreement. The signal to noise ratio (adequate Percision) greater than 4 is desirable for using the models to navigate the design space and which is 226.077 and 42.39 for ξ0 and ηext respectively (Yu et al. 2008). No lack of fit has been observed in the ANOVA tables for any of the equation (p ≥ 0.05). Better precision and reliability of the experiments conducted has also been confirmed by relatively lower value of the coefficient of variation (C.V. = 10.61% & 9.08% for ξ0 and ηext respectively) (Yu et al. 2008).

The response surface curves and the contour plots were drawn for these responses representing interactive effect within the experimental design of any two independent variables on responses while maintaining other variables values constant at zero coded values. Contours of parabolic nature indicate a quite significant interaction between two independent variables (Goyal et al. 2011). The detailed analysis of both the responses is described as under.

3.2 Initial Lactic Acid Extraction Rate

The modified quardratic model represented by Eq. 6 satisfactorily explained the effect of six variables on initial extraction rate. The response surfaces 3D graphical shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 helped to visualize the interactive effect of variables on the initial extraction rate. Parabolic surface responses signify a significant interaction between them.

The effect of lactic acid concentration (cl) and sodium carbonate concentration (cs) on the initial extraction rate (ξ0) is illustrated in Fig. 2. The surface plot illustrates that ξ0 increases with the increase in cl as well as with the increase in cs.

It is due to the fact that an increase in cs enhances the ability of stripping phase for stripping the solute from the carrier solute complex at the external surface of internal droplets within the emulsion leading to reduction in concentration polarization at the surface. Hence with an increase in cl, the driving force in both, stagnant external aqueous film and membrane phase in accordance with the Fick’s law will be increased; hence the initial extraction rate has been observed increasing (Garcia et al. 2013). At low level of cs, a slight decline in ξ0 had been observed as cl approaches high level. This can be explained with context to the advancing front model that with the further increase in cl, (as it approaches high level) there is an increase in the diffusional path length due to which the emulsion globule mass transfer resistance contribution to the overall mass transfer resistance got augmented. Similarly at low level of cl, a slight decrease in ξ0 had been observed as cs approaches high level. This may be attributed to swelling in internal droplets of membrane at high cs due to water transport along with lactic acid thorough the organic phase, causing coalesce of the internal droplets and hence reduction in mass transfer area (Datta et al. 2003).

It is evident from Fig. 3 that with enhancement in phase ratio, Φ and lactic acid concentration, cl , ξ0 increases. As the Φ increases from low level to high level, more proportion of internal stripping phase will be available for encapsulation of lactic acid and moreover the membrane thickness will be got reduced causing decrease in mass transfer resistance in membrane phase (Peng et al. 2012). On the other hand, at low cl with the increase in Φ towards the high level, there is a slight decrease in ξ0. This may be attributed to the fact that the internal droplets size have increased causing reduction in the interfacial contact area between emulsion and feed phase, which may have started dominating the effect on mass transport with respect to the thinning of membrane phase continue with the increase of Φ. At low level of Φ, with the increase in cl towards its high level, there is a slight decrease in ξ0, owing to the fact that the low level of Φ causes reduction in the hold-up capacity of the stripping phase, i.e. the emulsion globules, leading to simultaneously decrement in mass transfer interfacial area and LA encapsulating capacity of the internal stripping phase (Peng et al. 2012). Moreover at low level of Φ, high cl causes more readily saturation of the internal droplet with LA in the peripheral region (Noah et al. 2016).

It can be observed from Fig. 4 that with the increase in phase ratio Φ and sodium carbonate concentration in internal phase cs,ξ0 increases due to the increase in availability of stripping agent and capacity of internal phase for encapsulating the lactic acid. However at low Φ, with the increase in cs towards its high level, there is a slight decrease in ξ0, since high cs will increase the pH of stripping phase and may resulted in osmotic swelling due to high pH difference between the external and stripping phase. This leads to water transportation from the external to internal phase causing enhancement in the internal emulsion volume, which in turn decreases the area for mass transfer and moreover diffusion resistance increases in membrane phase due to the thickening of the membrane which tends to maintain the emulsion stability under low Φ (Ng et al. 2010). At low cs, a slight decrease in ξ0, has also been observed with the increase in Φ at high level increases the ELM.

volume owing to the decrease in the contact area (Goyal et al. 2011) and due to the low difference of electrolyte concentration between the stripping and external phases.

The variation in the extent of ξ0 due to the interactive effect of ω and cs is represented in Fig. 5. Since the contours are parabolic which signify a quite significant interaction between both the parameters. ω and cs are correlated to reach other by the fact that internal phase droplet size is a function of stirring speed and viscosity, while the latter is directly proportional to cs (Goyal et al. 2011). The stirring speed governs the mass transfer of solute across the membrane phase (Mesli and Belkhouche 2018). ξ0 tends to increase with the increase in both the variables upto a certain level, but towards the higher level of ω and cs, ξ0 decreases. With the increase in stirring speed during extraction, the shear force acting on the emulsion globule increases, which in turn deceases the average emulsion globules radius. Hence thereby causing an increase in the mass transfer rate due to increase in the interfacial area between feed phase & the membrane phase and reduction in the LA diffusion path length within the globules (Kumbasar 2012; Eyupoglu and Kumbasar 2015). Since viscosity is directly proportional to stripping phase concentration, hence high cs hinders the formation of smaller size emulsion globules at high ω. Moreover mass transfer resistance due to turbulence and the membrane swelling also got aggravated at higher ω (Peng et al. 2012; Mesli and Belkhouche 2018; Eyupoglu and Kumbasar 2015). At lower stirring speed, the interfacial contact area and mass transfer between external phase and emulsion decreases due to larger globule size. At low cs, the stripping rate of lactic acid is the limiting step in the system. This could be caused by saturation of lactic acid in organic phase due to low stripping rate (Reis et al. 2011).

The Interactive effect of treatment ratio, ψ and fraction of carrier φ, on ξ0 is illustrated in Fig. 6. ξ0 increases with the decrease in ψ and increase in φ. It may account for the reason that though the increase in φ leads to a higher amount of carrier solute complex at external-organic membrane interface which improves the selectivity (Mousavi et al. 2012; Lee 2013; Kumbasar 2010), while decrease in ψ results in increase in the number of emulsion globules per unit external phase volume causing an increase in the membrane surface area, the emulsion phase hold up, along with simultaneously an increase in the amount of carrier and the transport capacity of the emulsion liquid membrane (Gao et al. 2009; Kumbasar 2012). This may have steered an increase in ξ0 with the decrease in ψ and increase in φ. Minimum value of ξ0 has been depicted by the figure at high level of ψ and low level of φ which indicated the carrier unavailability in the membrane phase due it saturation due to complex formation at the interface as the lactic acid amount in the external phase has increased while that of carrier in the membrane phase has decreased (Noah et al. 2016).

3.3 Extraction Efficiency

The interactive effect of sodium carbonate concentration (cs) and lactic acid concentration (cl) on ηext had been illustrated in Fig. 7. ηext had been found to be increased with the increase in cs irrespective of cl, but more profoundly at low level of cl. This may be attributed to the higher hydrogen ion difference between the feed and stripping phase due to the larger reaction potential of Na2CO3 with lactic acid at its higher initial concentration. The hydrogen ion difference will be higher for minimum cl and maximum cs (Lee 2011). ηext had been found to decrease with the increase in cl irrespective of cs.

The 3D graphs depicts that decline in ηext is more at low value of cs. This can be explained with reference to the consideration of advancing front model for emulsion liquid membrane such that as the cl in aqueous phase increases, internal droplets in the peripheral region of emulsion got saturated more rapidly causing increase in the length of the diffusional path through the emulsion globule So, generating the necessity of more stripping reagent i.e. cs (Reis et al. 2011). Hence mass transfer resistance in the membrane phase becomes important at high cl, whereas, for low cl, external mass transfer is rate controlling. Towards higher level of cs, irrespective of cl, ηext tends to leveled off may be owing to the fact that initially increment in cs causes decrease in the mean droplet size of emulsions but further increase in cs after attaining its certain value, leads to increase in interfacial tension making emulsions unstable resulting in larger droplet size (Patti et al. 2012).

The effect of lactic acid concentration (cl) and fraction of carrier in n-hexane (φ), on ηext has been depicted in Fig. 8. It is observed that the effect of φ on ηext is more significant at low values of cl. For low values as well as high values of  the increment of cl causes gradual decreasing of ηext. At higher level of cl the increasing of φ also leads to enhancement of ηext, which is almost becoming constant at high level of φ. This may be due to reason that with the increase in carrier concentration, thickness of membrane wall increases due to increase in viscosity causing decrease in diffusion coefficient (Yordanov and Boyadzhiev 2004). Since the aqueous-organic interface has been flooded with lactic acid molecules at higher cl and higher interfacial resistance would be spawned as surfactant and carrier molecules in larger number will be contending at the interface for the adsorption sites (Basualto et al. 2006). Moreover higher carrier concentration causes increase in interfacial tension causing formation of larger size emulsion globules hence lesser surface area availability for mass transfer (Benyahia et al. 2014).

the increment of cl causes gradual decreasing of ηext. At higher level of cl the increasing of φ also leads to enhancement of ηext, which is almost becoming constant at high level of φ. This may be due to reason that with the increase in carrier concentration, thickness of membrane wall increases due to increase in viscosity causing decrease in diffusion coefficient (Yordanov and Boyadzhiev 2004). Since the aqueous-organic interface has been flooded with lactic acid molecules at higher cl and higher interfacial resistance would be spawned as surfactant and carrier molecules in larger number will be contending at the interface for the adsorption sites (Basualto et al. 2006). Moreover higher carrier concentration causes increase in interfacial tension causing formation of larger size emulsion globules hence lesser surface area availability for mass transfer (Benyahia et al. 2014).

The interactive effect of lactic acid concentration (cl) and contact time, τ on extraction efficiency, ηext is evident from Fig. 9. At low level of cl, ηext increases more rapidly with the incremental of τ in comparison to high level of cl. It can be due to the fact that at high level of cl during extraction, the peripheral region of emulsion could be got saturated by the earlier transported lactic acid into the stripping phase, and the lactic acid-amine complex now must diffuse to the more inner region of the emulsion through the membrane phase to liberate lactic acid into stripping phase Daas and Hamdaoui 2010). It is also evident from the figure that at any level of τ, the ηext increases more rapidly at low level of cl in comparison to high level of cl, which may be owing to the fact that at high cl concentration gradient at external phase-membrane phase interface is unfavorable causing carrier saturation effect (Anitha et al. 2015).

In the ELM process, φ and cs are the true representative of interactive extraction and stripping reaction processes in taking place in series respectively as both are the competitors for limiting reactant i.e. LA (Goyal et al. 2011). Extraction efficiency, ηext has been found to rise with the increase in cs for any value of φ (fraction of carrier in hexane) (Fig. 10), since the encapsulation capacity of lactic acid in stripping phase increases with the increase in cs which makes it possible the faster regeneration of TOA/TDA molecules rendering it available at faster rate for carrier-solute complex formation at the external phase-membrane interface and lowers the accumulation of solute-carrier complex at the interfaces of membrane phase causing faster lactic acid extraction (Anitha et al. 2015). At high level of cs,ηext increases with the increase in φ, but at low level of cs,ηext doesn’t show any significant increase may be owing to the fact that enough stripping agent was not available in the emulsion for the encapsulation of lactic acid.

The effect of contact time and sodium carbonate concentration on extraction efficiency has been illustrated in Fig. 11. ηext increases initially slightly and then become steady state at high level with the incremental of contact time, τ at low level of cs. This may be due the fact that the stripping agent present in the emulsion had got exhausted early.

At high level of cs, ηext increases with the incremental of τ owing to the normal permeation mechanism. ηext had been found to be increasing with the decrease in treatment ratio, ψ for any level of φ (Fig. 12), though the increment is more at high level of φ in comparison to that of at low level of φ, since carriers provide high distribution coefficient due to their tendency to form ion pair association of the alkyl ammonium cation with the acid anion (Keshav et al. 2012). At high level of ψ, there was no significant increase in ηext, due to lack of proper dispersion of emulsion globules for lactic acid encapsulation. At low level of ψ, ηext shows an increasing trend with the incremental of φ, and tends to achieve a constant value towards higher level. Since, at higher external phase volume: membrane phase volume ratio (i.e. low treatment ratio) and higher carrier concentration in the membrane phase there is a tendency of emulsion swelling due to a hydrated surfactant, which facilitate the water diffusion across the membrane along-with lactic acid, hence stopping the further increase in lactic acid extraction (Anitha et al. 2015).

It is evident from Fig. 13 that ηext increases with the increment in τ and Φ. The increment in ηext is higher at high level of τ and Φ in comparison to that at low level of τ and Φ. With the increase in Φ the thickness of the wall of the membrane globule decreases, causing decrease in distance to be traveled by the lactic acid-carrier complex relatively between the two interfaces, thereby increasing ηext (Goyal et al. 2011a).

3.4 Optimization of Lactic Acid Extraction

The numerical optimization technique was applied for obtaining the optimum value of process variables to maximize the responses (initial extraction rate and extraction efficiency). The statistical optimization of six variables for ξ0 and seven variables for ηext was done separately. The optimum values of process variables, cl, cs,φ, ψ, Φ and ω obtained were 0.5 [M], 0.2 [M], 4.57 (%,v/v), 0.50 (v/v), 0.70 (v/v) and 200 rpm respectively for ξ0, while for ηext, the optimum values of process variables, cl, cs,φ, ψ, Φ, ω and τ were 0.16 [M], 0.25 [M], 3.20 (%,v/v), 0.50 (v/v), 0.50 (v/v), 110 rpm and 9.75 min respectively. The initial extraction rate, ξ0 and extraction efficiency, ηext were predicted at the values of 9.36 × 10−9 [mol/cm2/s] and 98.5% under these optimized values, respectively. The synergy between the model predicted values for the process responses and those of experimentally observed values under optimized conditions has demonstrated that mass transfer phenomenon during the ELM process was adequately described by the respective mathematical models obtained during analysis of variance. So the design of experiments and subsequently optimization of process parameters by BBD for lactic acid extraction by ELM has shown a promising prospective on economical, environmental, time and technological aspects in comparison to conventional procedures/processes.

3.5 Validation of Results

Experiments were performed in triplicate for validation of the results predicted by the model under the optimized conditions for initial extraction rate and extraction efficiency. A close agreement between the predicted model values and experimental results was observed. The relative error was found to be within ±1.4% and ± 1.5% for the initial extraction rate and extraction efficiency, respectively. It indicates that the process statistical modeling is appropriate and fulfills the optimization objective.

4 Conclusion

Response surface methodology has successfully optimized the LA extraction by emulsion liquid membrane technology. The experimental design, regression analysis, and quadratic models hence developed for the initial extraction rate and extraction efficiency were observed to be reasonably accurate and efficient in forecasting the response value within the ranges of the variables investigated. The optimum value of contact time of 9.75 min along with optimized conditions of other process parameters for achieving the 98.5% extraction efficiency with an initial rate of extraction of 9.36 × 10−9 [mol/cm2/s] has demonstrated the ability of ELM to achieve considerably high degree of separation at a very rapid rate. The contour and 3D graphs has provided the insight about the interactive effect of process parameters on the ELM process efficiency for lactic acid extraction under the synergic effect of mixture of tertiary ammines.

References

Ahmad AL, Buddin MMHS, Ooi BS, Kusumastuti A (2017) Utilization of environmentally benign emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) for cadmium extraction from aqueous solution. J Water Process Eng 15:26–30

Anitha M, Ambare DN, Singh DK, Singh H, Mohapatra PK (2015) Extraction of neodymium from nitric acid feed solutions using an emulsion liquid membrane containing TOPO and DNPPA as the carrier extractants. Chem Eng Res Des 98:89–95

Babu VS, Kumar SS, Murali RV, Rao MM (2011) Investigation and validation of optimal cutting parameters for least surface roughness in EN24 with response surface method. Inter J Eng, Sci and Technol 3(6):146–160

Basualto C, Poblete M, Marchese J, Ochoa A, Acosta A, Sapaga J, Valenzuela F (2006) Extraction of cadmium from aqueous solutions by emulsion liquid membranes using a stirred transfer cell contactor. J Braz Chem Soc 17(7):1347–1354

Benyahia N, Belkhouche N, Jonsson JA (2014) A comparative study of experimental optimization and response surface methodology of bi(III) extraction by emulsion organophosphorus liquid membrane. J Environ Chem Eng 2:1756–1766

Berrios J, Pyle DL, Aroca G (2010) Gibberellic acid extraction from aqueous solutions and fermentation broths by using emulsion liquid membranes. J Membr Sci 348:91–98

Chanukya BS, Rastogi NK (2013) Extraction of alcohol from wine and color extracts using liquid emulsion membrane. Sep Purif Technol 105:41–47

Daas A, Hamdaoui O (2010) Extraction of bisphenol a from aqueous solutions by emulsion liquid membrane. J Membr Sci 348:360–368

Datta S, Bhattacharya PK, Verma N (2003) Removal of aniline from aqueous solution in a mixed flow reactor using emulsion liquid membrane. J Membr Sci 226:185–201

Eyupoglu V, Kumbasar RA (2015) Extraction of Ni(II) from spent Cr-Ni electroplating bath solutions using LIX 63 and 2BDA as carriers by emulsion liquid membrane technique. J Ind Eng Chem 21:303–310

Gao MT, Shimamura T, Ishida N, Takahashi H (2009) Application of metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae to extractive lactic acid fermentation. Biochem Eng J 44:251–255

Garavand F, Razavi SH, Cacciotti I (2017) Synchronized extraction and purification of L-lactic acid from fermentation broth by emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) technique. J Dispers Sci Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/01932691.2017.1396225

Garcia MG, Acosta AO, Marchese J (2013) Emulsion liquid membrane pertraction of Cr(III) from aqueoussolutions using PC-88A as carrier. Desalination 318:88–96

Goyal RK, Jayakumar NS, Hashim MA (2011) A comparative study of experimental optimization and response surface optimization of Cr removal by emulsion ionic liquid membrane. J Hazard Mater 195:383–390

Goyal RK, Jayakumar NS, Hashim MA (2011a) Chromium removal by emulsion liquid membrane using [BMIM]+[NTf2]− as stabilizer and TOMAC as extractant. Desalination 278:50–56

Hachemaoui A, Belhamel K (2017) Simultaneous extraction and separation of cobalt and nickel from chloride solution through emulsion liquid membrane using Cyanex 301 as extractant. Int J Miner Process 161:7–12

Hong YK, Hong WH (1999) Reactive extraction of lactic acid with mixed tertiary amine extractants. Biotechnol Tech 13:915–918

Hong L, Yimin Z, Jing H, Tao L, Nannan X, Kui W (2017) Selective separation and recovery of vanadium from a multiple impurity acid leaching solution ofstone coal by emulsion liquid membrane using di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid. Chem Eng Res Des 122:289–297

Jiao H, Peng W, Zhao J, Xu C (2013) Extraction performance of bisphenol a from aqueous solutions by emulsion liquid membrane using response surface methodology. Desalination 313:36–43

John RP, Nampoothiri KM, Pandey A (2007) Fermentative production of lactic acid from biomass:an overview on process developments and future perspectives. Appl Microb Biotechnol 74:524–534

Keshav A, Norge P, Wasewar KL (2012) Reactive extraction of citric acid using tri-n-octylamine in nontoxic natural diluents: part 1-equilibrium studies from aqueous solutions. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 167:197–213

Kimberley AC, Taylor CA (1996) A simple colorimetric assay for muramic acid and lactic acid. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 56:49–58

Kumbasar RA (2010) Extraction and concentration of cobalt from acidic leach solutions containing co-Ni by emulsion liquid membrane using TOA as extractant. J Ind Eng Chem 16:448–454

Kumbasar RA (2012) Selective transport of cobalt (II) from ammoniacal solutions containing cobalt (II) and nickel (II) by emulsion liquid membranes using 8-hydroxyquinoline. J Ind and Eng Chem 18:145–151

Kyuchoukov G, Marinova M, Molinier J, Albet J, Malmary G (2001) Extraction of lactic acid by means of a mixed extractant. Ind & Eng Chem Res 40:5635–5639

Lee SC (2011) Extraction of succinic acid from simulated media by emulsion liquid membranes. J Membr Sci 381:237–243

Lee SC (2013) Development of an emulsion liquid membrane system for removal of acetic acid from xylose and sulfuric acid in a simulated hemicellulosic hydrolysate. Sep and Purif Technol 118:540–546

Li Y, Shahbazi A (2006) Lactic acid recovery from cheese whey fermentation broth using combined ultrafiltration and nanofiltration membranes. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 132(1–3):985–996

Mesli M, Belkhouche N-E (2018) Emulsion ionic liquid membrane for recovery process of lead. Comparative study of experimental and response surface design. Chem Eng Res Des 129:160–169

Mousavi SM, Kiani S, Farmad MR, Hemati A, Abbasi B (2012) Extraction of arsenic(V) from water using emulsion liquid membrane. J Disper Sci Tech 33:123–129

Ng YS, Jayakumar NS, Hashim MA (2010) Performance evaluation of organic emulsion liquid membrane on phenol removal. J Hazard Mater 184:255–260

Noah NFM, Othman N, Jusoh N (2016) Highly selective transport of palladium from electroplating wastewater using emulsion liquid membrane process. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 64:134–141

Patti GCA, Llinàs M, García-Celma MJ (2012) Diffusion in highly concentrated emulsions. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 17:255–260

Peng W, Jiao H, Shi H, Xu C (2012) The application of emulsion liquid membrane process and heat-induced demulsification for removal of pyridine from aqueous solutions. Desalination 286:372–378

Pimtong, V.; Ounaeb, S.; Thitiprasert, S.; Tolieng,V.; Sooksai, S.; Boonsombat, R.; Tanasupawat, S.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Thongchul, N. (2017) Enhanced effectiveness of Rhizopus oryzae by immobilization in a static bed fermentor for l-lactic acid production. Process Biochem 52: 44–52

Rajasimman M, Karthic P (2010) Application of response surface methodology for the extraction of chromium (VI) by emulsion liquid membrane. J Taiw Inst Chem Eng 41:105–110

Reis MT, Freitas OM, Agarwal S, Ferreira LM, Ismael MR, Machado R, Carvalho JM (2011) Removal of phenols from aqueous solutions by emulsion liquid membranes. J Hazard Mater 192(3):986–994

Uslu H, Bayat C, Gokmen S, Yorulmaz Y (2009) Reactive extraction and LSER model consideration of lactic acid with tripropylamine+ organic solvent systems from aqueous solution at room temperature. Desalination 249:694–698

Venus J, Fiore S, Demichelis F, Pleisser D (2018) Centralized and decentralized utilization of organic residues for lactic acid production. J Clean Prod 172:778–785

Yankov D, Molinier J, Albet J, Malmary G, Kyuchoukov G (2004) Lactic acid extraction from aqueous solutions with tri-n-octylamine dissolved in decanol and dodecane. BiochemEng J 21:63–71

Yetilmezsoy K, Demirel S, Vanderbei RJ (2009) Response surface modeling of Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution by Pistaciavera L.: box-Behnken experimental design. J Hazard Mater 171:551–562

Yordanov B, Boyadzhiev L (2004) Pertraction of citric acid by means of emulsion liquid membranes. J Membr Sci 238:191–197

Yu L, Lei T, Ren X, Pei X, Feng Y (2008) Response surface optimization of l-(+)-lactic acid production using corn steep liquor as an alternative nitrogen source by Lactobacillus rhamnosus CGMCC 1466. Biochem Eng J 39:496–450

Acknowledgements

Author is grateful to Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, India for providing the lab facilities and all necessary help to perform this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thakur, A. Lactic Acid Extraction from Aqueous Systems by Emulsion Liquid Membrane Separation Process Using Statistical Experimental Design. Polytechnica 2, 62–76 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41050-019-00015-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41050-019-00015-0