Abstract

The current study examined the effects of acceptance of thoughts, mindful awareness of breathing, and spontaneous coping on both pain tolerance and pain threshold during a cold pressor task. Eligible participants (N = 58), 16 males and 42 females (M age = 29.31, SD = 11.21), were randomized into three groups and completed two cold pressor trials. The first cold pressor trial formed a baseline for all three groups. The acceptance of thoughts and mindfulness of breathing groups listened to recorded instructions and then completed a second administration of the cold pressor task. The spontaneous coping group completed the cold pressor task twice with instructions to select their own coping style. Multilevel linear modeling showed significant group differences in pain tolerance. The acceptance of thoughts and mindfulness of breathing conditions resulted in significantly higher pain tolerance in post hoc analysis than spontaneous coping. Results were interpreted to be consistent with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Further examination of the effects of ACT processes on experimentally induced pain tolerance is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a therapeutic technology that has its roots in radical behaviorism and has extended this with a theory of verbal behavior entitled Relational Frame Theory (Hayes 2004). The ACT model consists of six key processes, including contact with the present moment, acceptance, defusion, self-as-context, committed action, and values (Hayes et al. 2012). The goal of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility, which is the ability to contact the present moment more fully and to change or persist in behavior that serves valued ends (Fletcher and Hayes 2005). With regard to pain, ACT is now an empirically tested psychological intervention for pain treatment and has recently been listed by Division 12 of the American Psychological Association as an empirically supported treatment for chronic pain with strong support (http://www.div12.org). This paper examines at a technical level two rationales that focus on two elements of the psychological flexibility ACT model—acceptance and being present.

The acceptance component of ACT has been widely evaluated for pain. Acceptance is the active process of having aversive thoughts or emotions and letting oneself experience them, rather than using escape and avoidance strategies to attempt to stop the experience. ACT research shows that the opposite of acceptance, avoidance of private experiences, contributes to psychological inflexibility, which leads to narrower repertoires of behavior, loss of meaning in life, and greater psychopathology (Hayes et al. 2006). Interventions successfully utilizing acceptance include multidisciplinary programs for chronic pain sufferers (McCraken et al. 2005; Wicksell et al. 2008a), highly disabled patients with chronic pain (McCraken et al. 2007), and pediatric patients suffering chronic pain (Wicksell et al. 2008b). Acceptance has been shown to be effective with pain experiences that are outside one’s ability to control, specifically chronic pain, which includes unwanted thoughts or bodily sensations (Hayes et al. 2012; Keogh et al. 2005). In this experiment, the acceptance component is explicitly defined as acceptance of thoughts that relate to physical pain.

Mindfulness is a confusing term due to its widespread uses across religious traditions, meditation practices, and of course therapeutic models, including ACT (Hayes et al. 2012), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal et al. 2002), and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Mindfulness includes, but is not limited to, concentration, single-pointed focused awareness, adopting an attitude of being in the here and now, and achieving insight (Mikulas 2011). Using this broad definition, it could be argued that the ACT model includes mindfulness across the six processes, and especially in the processes of acceptance, present moment, defusion, and self-as-context (Hayes et al. 2012). One difficulty with mindfulness is technical preciseness on how mindfulness is defined, how it has been used, and its overlap with acceptance. In a therapeutic context, broadly defined, mindfulness may have the potential to influence other processes within the ACT model. To counter this, we use single-pointed awareness of the breath as the experimental mindfulness component because it falls within the ACT process of being present and it is clearly distinct from acceptance of thoughts.

This study tests acceptance and mindfulness protocols (as defined above) using an induced pain task. The experimental effects of acceptance of unwanted thoughts on pain tolerance have been examined across a number of conditions. The most commonly used method to induce pain is the cold pressor task (Graven-Nielsen et al. 2001). The cold pressor generally holds water maintained between 0º and 2 ºC (Graven-Nielsen et al. 2001) and is considered as a safe form of pain induction, while also demonstrating good reliability and validity (Edens and Gil 1995; Graven-Nielsen et al. 2001).

Hayes et al. (1999) used the cold pressor pain induction task to compare the effect of an acceptance rationale with a traditional control method for coping with pain. Using an independent group design and presenting 90-min interventions of acceptance, thought control, or attention placebo with undergraduate university participants, they found that participants in the acceptance group scored significantly higher on pain tolerance than participants in the thought control or attention placebo groups. Hayes et al.’s study was then replicated and extended in a Japanese sample by Takahashi et al. (2002), where the authors found acceptance, combined with ACT exercises designed to undermine the impact of painful thoughts, produced significantly higher pain tolerance scores on a cold pressor task when compared to thought suppression or placebo groups. Findings suggest that the incorporation of an acceptance exercise with related background information on ACT may further serve to increase pain tolerance in a cold pressor task (Takahashi et al. 2002). Acceptance rationales have also been found to result in significantly higher pain tolerance when compared with suppression and spontaneous coping rationales in a large sample (N = 219) of undergraduate students (Masedo and Esteve 2007). Furthermore, pain suppression was found to produce the shortest pain tolerance time.

Although acceptance has been consistently tested in controlled experiments, mindfulness tests are fewer. Mindfulness techniques, defined broadly, have been shown to be effective across a range of measures in chronic pain populations (Baer 2003; McCraken et al. 2007; Morone et al. 2008). However, experimental tests of mindfulness would benefit from more precise definitions and subsequent testing. When utilized in experimental pain tasks, the effects of mindfulness on pain tolerance either have gone unmeasured with a focus on other aspects of the pain experience (Zeidan et al. 2010) or have been unable to attribute any increased pain tolerance to the acquisition of mindfulness skills (Kingston et al. 2007). Hence, mindfulness has not been clearly defined or tested adequately under strict experimental conditions using a standardized task of pain tolerance.

In summary, a mindfulness protocol has not been directly compared to an acceptance protocol or spontaneous coping condition in an experimentally induced pain task. Furthermore, reliable experimental research using mindfulness that is broadly defined is at best limited and at worst methodologically flawed. Masedo and Esteve (2007) have argued for the importance of undertaking comparisons of the effectiveness of different psychological strategies, including those that may be spontaneously used. The protocols of acceptance and mindfulness were adopted for the current study with the intention of examining the effects they may have on pain tolerance at a technical level. Specifically, the present study compared acceptance of thoughts, mindful awareness of breathing, and spontaneous coping using experimental conditions and testing pain induced using a cold pressor task. It was hypothesized that acceptance of thoughts and mindfulness awareness of breathing rationales would result in significantly higher pain tolerance and pain threshold on a cold pressor task than spontaneous coping. Further exploratory analysis aimed to examine any differences in pain tolerance for males and females and also individuals identified as high and low experiential avoiders.

Method

Participants

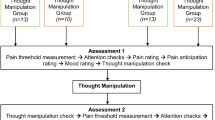

Sixty-seven participants were included, 42 undergraduates and 25 participants from the broader community. Undergraduate psychology students received course credit for participation in the study, and community participants were recruited through community advertisements. Community participants received no form of incentive or payment for their participation. All participants signed informed consent forms and completed an initial health screening prior to undergoing the task. Participants were randomly allocated into three independent groups using a computer-generated random allocation program (see Fig. 1).

Nine participants were excluded for having naturally high pain tolerance. This was set at 300 s on the baseline cold pressor trial, and followed the same exclusion criteria as Masedo and Esteve (2007). The final data sample (N = 58) comprised 67.3 % psychology undergraduates and 32.7 % community volunteers, with participants ranging in age from 18 to 61 years (M age = 29.31, SD = 11.21).

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

This was a brief questionnaire designed to obtain basic demographic information, including age and sex, from participants.

Pain Tolerance

Pain tolerance was the length of time that a participant kept his or her hand and forearm immersed in the water, measured in seconds with a digital stopwatch.

Pain Threshold

Pain threshold was the length of time until a participant indicated verbally that he or she was experiencing discomfort, measured in seconds with a digital stopwatch.

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al. 2011) is a 10-item self-report measure of experiential avoidance that is keyed positively (Hayes et al. 2004). The AAQ-II was utilized in the current study as a screening measure for individuals both high and low in experiential avoidance. Participants indicate the degree to which the ten items apply to their thoughts. Sample items from the AAQ-II include “I’m afraid of my feelings” with responses made on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). The AAQ-II has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 and therefore demonstrates good internal consistency (Bond et al. 2011). The Cronbach’s alpha achieved in the current study was 0.80. Higher scores on the AAQ-II are reflective of greater psychological flexibility, higher acceptance, and lower experiential avoidance. Conversely, lower scores are characteristic of lower psychological flexibility, lower acceptance, and higher experiential avoidance.

The Coping Strategies Questionnaire

A modified version of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ; Rosenstiel and Keefe 1983) consisting of six subscales was used for the current study. The Increasing Behavioral Activity subscale from the original CSQ was deleted, as were two items from the Praying/Hoping scale deemed to be inappropriate to coping with a cold pressor task. The remaining subscales, Diverting Attention, Reinterpreting Pain Sensations, Coping Self-Statements, Ignoring Pain Sensations, Praying/Hoping, and Catastrophizing, were utilized to assess differences in coping by sex and high and low experiential avoidance at post-baseline cold pressor. Scores for each of the subscale items were summed with higher scores indicating higher use of that strategy. This modified measure was developed by Geisser et al. (1992) specifically for cold pressor tasks. The 36 items, worded in past tense, required participants to rate their specific coping strategies while undertaking the cold pressor task. Examples of these include, “when I felt pain, ‘I tried to think of something pleasant.’” Participants rated each of the 36 items on a 7- point scale ranging from 0 (never did that) to 6 (always did that). The current study recorded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Usefulness, Difficulty, and Frequency

The measure of Usefulness, Difficulty, and Frequency (Gutierrez et al. 2004) is designed to ascertain the usefulness, level of difficulty, and frequency of use that is associated with the adopted method for dealing with pain. The questionnaire is a visual analogue scale format. The questionnaire delivered to control group participants first asks, “What method did you use to mainly cope with the pain?” The questionnaire delivered to participants in the experimental condition does not ask for method of coping; instead it informs participants to rate responses based on the previously delivered acceptance or mindfulness directions. Participants from control and experimental conditions then answer the following questions based on their method of coping. Question 1 = How useful was the rationale for you in continuing with the second pain task? (0-to-10 scale); Question 2 = How difficult was it to use the strategy during the second pain task? (0-to-10 scale); Question 3 = How often did you practice the strategy during the second pain task? (0-to-3 scale). Scores are assessed by measuring participant responses along a visual analogue scale and recording it in centimeters.

Apparatus

A cold pressor apparatus consisting of a 65-litre cooler (38 cm wide, 70 cm long, and 33 cm deep), filled with water and maintained at a temperature range of 0–2 ºC was utilized. A 12-V AquaPro™ AP3000 submersible pump was placed into one end of the cold pressor apparatus to ensure continued circulation of the water. This was undertaken to prevent microenvironments from forming around the participant’s arms. The circulation provided by the submersible pump also restricted the movement of ice to the opposite end of the apparatus. This prevented direct contact between ice and the participant’s arm. The water temperature was monitored with the use of an LCD digital thermometer sensitive to temperatures ranging from −50 ºC to +300 ºC and accurate to within ±1 ºC. The cold pressor was used as the method for inducing acute pain in participants as it is considered a safe method with both good reliability and validity (Edens and Gil 1995; Keogh et al. 2005; von Baeyer et al. 2005). The method of experimental pain induction received clearance by the ethics committee of the University of Ballarat.

The acceptance and mindfulness tasks were operationalized in the form of brief pre-recorded rationales consistent with the ACT research and protocols (Appendixes 1 and 2). Both were recorded by a female ACT practitioner who is recognized as an ACT trainer, and were stored on an audio file. The acceptance rationale was a direct replication of the acceptance task tested in previous cold pressor research by Keogh et al. (2005), with slight modifications to suit the sample of participants. The mindfulness rationale was a brief pre-recorded mindfulness exercise from widely used mindfulness of breathing instructions (Harris 2009), with minor adaptations to suit the task.

Experimental Design

The experimental design consisted of three independent groups: (a) acceptance of thoughts, (b) mindfulness awareness of breathing, and (c) spontaneous coping (see Fig. 1). Dependent variables included pain threshold, pain tolerance, self-reports from the CSQ and the Usefulness, Difficulty, and Frequency measure. The AAQ-II was used as a screening instrument delivered prior to the first cold pressor task. First, all three groups completed a baseline trial of the cold pressor task (shown in Fig. 1) with instructions to cope with the pain in any way they chose (spontaneous coping). The acceptance group then listened to a pre-recorded acceptance rationale prior to completing the cold pressor task for a second time. The mindfulness group listened to a pre-recorded mindfulness rationale and then completed the cold pressor task for a second time. The spontaneous coping group completed the cold pressor task a second time, with instructions to cope with the pain in any way they chose.

Procedure

Participants received a brief explanation stating that they would be participating in an experimental pain study using a cold pressor task and then completed the health screen previously described and gave informed consent. Participants were then seated in a comfortable chair in a room containing no clock. To avoid self-monitoring, timepieces and mobile phones were removed and the AAQ-II was then completed. Participants were instructed on how to report pain threshold and tolerance. Participants were instructed to use any coping method they preferred. Following these instructions, participants placed their non-dominant arm on the armrest and immersed it to approximately 5 cm below the elbow and completed the baseline trial. On completion of the baseline cold pressor task, the CSQ and Usefulness, Difficulty, and Frequency measure were completed. Participants only received the CSQ after the baseline cold pressor.

The researcher followed a standard procedure during cold pressor trials to reduce demand characteristics. This included providing no encouraging reinforcement, avoiding close proximity, and avoiding eye contact. It has been demonstrated that demand characteristics such as these can significantly influence a participant’s pain tolerance in cold pressor tasks (Roche et al. 2007; von Baeyer et al. 2005).

Prior to the second cold pressor administration, participants in the acceptance condition listened to either the pre-recorded acceptance of thoughts rationale (Appendix 1) or the pre-recorded mindfulness of breathing rationale (Appendix 2); these were delivered through a laptop computer with headphones. The spontaneous coping group received the same instructions prior to the first cold pressor trial asking them to use any coping method they preferred (spontaneous coping). Each group then completed a second cold pressor trial before completion of the Usefulness, Difficulty, and Frequency measure.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was undertaken over four stages. Stage 1 of analysis involved the initial screening of the data and exclusion of participant scores that had reached the experimental ceiling of 300 seconds at the baseline sitting of the cold pressor task. Examination of data sets for normality and outliers was also undertaken (N = 58). While the AAQ-II and the CSQ met normality assumptions, pain tolerance and pain threshold scores were skewed and violated the linearity assumption needed to perform analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs). Stage 2 involved testing for experimental effects on pain tolerance and pain threshold scores between conditions. Due to normality violations, multilevel linear modeling was used to examine the effects of acceptance and mindfulness on pain threshold and pain tolerance. Multilevel linear models do not rely on the assumptions of homogeneity of regression slopes (Field 2009). All other assumptions related to regression were met. Multicollinearity testing revealed no strong linear relationship between predictors. Homoscedasticity was assumed, as were normally distributed errors. Stage 3 involved testing for sex differences in pain tolerance on baseline cold pressor scores using Mann–Whitney U tests. Finally, Stage 4 was exploratory analyses (using data collected after the first cold pressor trial) examining differences in coping style (CSQ) and pain tolerance scores for those classified by the AAQ-II as being high and low in experiential avoidance.

Results

Group Differences in Pain

Pain tolerance was measured as the length of time the participant kept his or her hand or forearm in the water. For pain tolerance, the best fitting model was a random intercept and slope, F(2, 108.96) = 6.35, p = 0.01. This model revealed a significant difference in pain tolerance between the three conditions. Figure 2 displays the difference in mean pain tolerance scores between each experimental condition, revealing the significantly higher pain tolerance scores of acceptance and mindfulness following the second cold pressor. As shown in Table 1, post hoc analyses with Bonferroni corrections revealed that individuals in the acceptance group achieved a significantly higher pain tolerance compared to baseline cold pressor trial (M diff = 43.11, p = 0.04, 95 % CIs [.63, 85.58]). Similarly, the mindfulness group was also significantly higher in pain tolerance for the second trial when compared to the baseline cold pressor trial (M diff = 66.05, p = 0.00, 95 % CIs [24.70, 107.39]). Conversely, the spontaneous coping group did not change significantly between baseline and the second cold pressor trial (M diff = 10.19, p = 1.00, 95 % CIs [29.13, 49.51]).

Pain threshold was measured as the interval of time before the participant stated that he or she was experiencing pain. For pain threshold, no significant difference was seen across time between the three conditions using multilevel linear model with random intercept and slope, F(2, 103.50) = 2.71, p = 0.07. This means that across the three conditions, participants did not differ significantly in the time it took for them to say they felt pain between their first cold pressor pain trial and their second cold pressor pain trial.

On the measures of Usefulness, Difficulty, and Frequency, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no significant differences for all three conditions (p > 0.05). This demonstrates that the acceptance and mindfulness instructions were perceived by participants to be as useful and no more difficult that the spontaneous coping method, and they were utilized as frequently.

Baseline Cold Pressor Sex Differences in Pain Tolerance and Pain Threshold

Finally, sex differences were examined for pain tolerance and pain threshold scores obtained at baseline. Non-parametric Mann–Whitney testing was used, as data were skewed and there were fewer male participants. On pain tolerance, males had significantly higher median pain tolerance scores (Md = 51.5, n = 16) than females (Md = 24.50, n = 42) at baseline measurement (U = 191.0, z = −2.52, p = 0.01, r = 0.33). On pain threshold, there were no significant differences between males and females recorded (males: Md = 13, n = 16; females: Md = 9, n = 42) at baseline (p = 0.17). Therefore, males tolerated the pain for longer periods, but the level of initial discomfort did not differ significantly. Further analysis revealed no significant differences between the six CSQ coping subscales.

Baseline Cold Pressor Differences in Low and High Experiential Avoidance

Analysis was undertaken to investigate differences between high and low experiential avoidance, as measured by the AAQ-II. Scores two standard deviations below the mean on the AAQ-II at baseline were used to identify participants with high experiential avoidance (n = 9), and scores two standard deviations above the mean were used to identify participants with low experiential avoidance recorded at baseline (n = 8). Mann–Whitney U non-parametric testing showed no significant difference in pain tolerance between high experiential avoidance and low experiential avoidance (U = 24, z = −1.15, p = 0.25, r = 0.27). The difference was also not significant for pain threshold (U = 35, z = −0.09, p = 0.92, r = 0.02).

However, with regard to coping strategies using the CSQ, those with high experiential avoidance were found to significantly engage in reinterpreting pain sensations (Md = 15) more frequently than the low experiential avoidance group (Md = 4; U = 8, z = −2.71, p = 0.01, r = 0.65). Reinterpreting pain sensations is a coping strategy that involves imagining something, which if real, would be inconsistent with the experience of pain (Rosenstiel and Keefe 1983). Individuals high on experiential avoidance were therefore significantly more likely to use the coping method of reinterpreting pain sensations during their baseline trial, in an attempt to modify their response to pain, with the intention of increasing pain tolerance. No further significant differences were found amongst the other coping strategies.

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to examine the effects of acceptance of thoughts, and mindfulness of breathing, when compared to spontaneous coping during a pain induction task. Consistent with our hypothesis, the acceptance and mindfulness conditions resulted in significantly higher pain tolerance than the spontaneous coping control condition. Results on pain threshold revealed no significant differences between groups, which failed to support the hypothesis that acceptance and mindfulness conditions would result in higher pain threshold. Exploratory analyses revealed that males were significantly higher in pain tolerance than females on the baseline cold pressor trial. Finally, no significant differences in pain tolerance or pain threshold were found for high or low experiential avoiders, although high experiential avoiders were more likely to reinterpret pain sensations than low experiential avoiders.

The results from the present study add to a growing body of findings that show that an acceptance protocol can result in a significantly higher pain tolerance in experimentally induced pain tasks, when compared with other coping methods, including control (Gutierrez et al. 2004; Keogh et al. 2005; Paez-Blarrina et al. 2008), suppression (Masedo and Esteve 2007), and thought control (Hayes et al. 1999; Takahashi et al. 2002). These current findings also build on the paucity of research related to the effects of mindfulness-related rationales and pain tolerance in an experimentally induced pain task (Kingston et al. 2007; Zeidan et al. 2010). Furthermore, by comparing mindfulness of breath to acceptance of thoughts protocols, for the first time, this study has highlighted the effects these two protocols demonstrate on pain tolerance at a technical level. This has resulted in a mindful awareness breathing rationale being shown to be as effective as an acceptance of thoughts rationale with regard to pain tolerance, with no significant difference being found between the two.

The current research findings revealed females that had significantly lower pain tolerance than males, albeit, with a limited sample of males. Lower pain tolerance in females is consistent with previous experimental pain research (Edwards et al. 2004; Keogh et al. 2005) and reported epidemiological literature (Berkley 1997; LeResche 2000). Engaging in catastrophizing has been posited as a potential explanation for sex differences, with the suggestion that females may engage in this coping strategy more than males (Edwards et al. 2004). The findings from the current study failed to support this explanation, with no significant differences being recorded between the sexes on the Catastrophizing scale, or any other coping scale, of the CSQ at baseline. This may, however, be an issue related to limited statistical power and warrants further exploration.

The acceptance of thoughts and mindfulness of breath rationales did not aim to alter the content of the participant’s thoughts experienced during the pain task; instead, the manipulations sought to change the participant’s responses to pain with the aim of producing a higher tolerance. This may help to explain why no significant differences were recorded between pain threshold scores. Individuals in the experimental conditions have still reported initial discomfort or pain threshold at similar times but have responded to pain sensations differently, which has resulted in a higher tolerance to pain. This interpretation is consistent with the theory of ACT. The mindfulness rationale resulted in a large effect size, whereas the acceptance rationale resulted in a medium effect size on pain tolerance. The mindfulness rationale may have acted on a more experiential level, as opposed to the acceptance rationale, which may have been interpreted as more didactic instruction. At baseline, participants in the experimental and control conditions had equivalent pain threshold ratings. Applying the theoretical model that underpins ACT, one could suggest that participants in the acceptance and mindfulness conditions achieved a higher pain tolerance than those in the control group because they did not respond with psychological avoidance, not because they felt the pain differently. Alternatively, as the current study did not ascertain whether the rationales were interpreted and acted upon in the theoretically intended manner, it cannot be concluded for certain that the rationales operated as specifically intended. Future research should seek to introduce adherence and comprehension measures post-rationale to address this.

Consistent with previous research, to establish high and low experiential avoiders, the current study compared scores that were two standard deviations above and below the mean on the AAQ-II (Zettle et al. 2005). No significant differences in pain tolerance between high and low experiential avoiders were found. The current study’s findings showed that high experiential avoiders engaged in reinterpreting pain sensations significantly more often than low experiential avoiders. This is in comparison to catastrophizing, which has been reported to be utilized significantly more by high experiential avoiders (Zettle et al. 2005). The extremely small groups of high and low experiential avoiders utilized for analysis in the present study is an area for concern. Any conclusions drawn from these exploratory findings should be considered tentatively in view of the small sample.

The strength of this study was the experimental design, random allocation of participants, and standardized manipulations. Nonetheless, some limitations were present. Of primary concern was the overselection of females and the underrepresentation of males. The small number of males resulted in the adoption of non-parametric tests for assessing sex differences. Furthermore, the unequal allocation of males and females throughout the conditions limited statistical analysis and conclusions for further sex differences. Equal allocation would have allowed analysis to determine whether certain experimental conditions benefitted one sex more. Although this was an exploratory aspect of the study, being able to undertake this further analysis may have provided informative additional information.

Finally, results achieved in this highly controlled environment utilizing experimental methods for inducing pain may be suggested as lacking generalizability. Given this, it could be argued that the current findings may be more applicable to the acute pain experience rather than chronic pain populations. However, the results appear to support the theoretical contention that psychological acceptance is more beneficial than avoidance strategies (Hayes et al. 1999).

The findings from the current study also hold meaningful implications for ACT. The outcome of this experimental pain research is consistent with ACT, showing that the protocols of both acceptance of thoughts and mindfulness of breath can result in significantly improved pain tolerance. Future research is needed that examines the effects of the remaining ACT processes at a technical level. Furthermore, the current study suggests that further research should consider utilizing and further developing mindfulness, across its various forms, in chronic pain populations to measure its effects. Control-based therapies that focus on altering the form and frequency of an individual’s thoughts have dominated most forms of pain management (Hayes et al. 1999). These findings support an alternative approach for treating pain, such as acceptance and non-evaluative noticing of internal events (Keogh et al. 2005). The positive implications associated with successful dissemination of third-wave research to clinical practice are considerable.

In conclusion, the current study has shown that brief pre-recorded acceptance of thoughts and mindful awareness–based breathing rationales were successful techniques for improving pain tolerance. Furthermore, it has shown that males had a significantly higher pain tolerance than their female counterparts, although this finding is cautionary due to the small sample of males. This study has addressed the paucity of research related to mindfulness present in the experimental pain literature. It has built on previous research by comparing a mindfulness breathing exercise for the first time with an acceptance of thoughts rationale in an experimental pain task. Acceptance and mindfulness conditions were confirmed as resulting in significantly higher pain tolerance than control conditions. It is hoped that future pain research will continue to compare the effectiveness of different third-wave processes in a range of different settings and populations.

References

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg015.

Berkley, K. J. (1997). Sex differences in pain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 20, 371–380.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688.

Edens, J. L., & Gil, K. M. (1995). Experimental induction of pain: Utility in the study of clinical pain. Behavior Therapy, 26(2), 197–216.

Edwards, R. R., Haythornthwaite, J. A., Sullivan, M. J., & Fillingim, R. B. (2004). Catastrophizing as a mediator of sex differences in pain: differential effects for daily pain versus laboratory-induced pain. Pain, 111, 335–341. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.012.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Fletcher, L., & Hayes, S. C. (2005). Relational frame theory, acceptance and commitment therapy, and a functional analytic definition of mindfulness. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 315–336. doi:10.1007/s10942-005-0017-7.

Geisser, M. E., Robinson, M. E., & Pickren, W. E. (1992). Differences in cognitive coping strategies among pain-sensitive and pain-tolerant individuals on the cold-pressor test. Behavior Therapy, 23, 31–41.

Graven-Nielsen, T., Sergerdahl, M., Svensson, P., & Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2001). Methods for induction and assessment of pain in humans with clinical and pharmacological examples. In L. Kruger (Ed.), Methods in pain research (pp. 263–304). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Gutierrez, O., Luciano, C., Rodriguez, M., & Fink, B. C. (2004). Comparison between an acceptance-based and a cognitive-control-based protocol for coping with pain. Behavior Therapy, 35, 767–783.

Harris, R. (2009). ACT made simple: An easy to read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35, 639–665.

Hayes, S. C., Bissett, R. T., Korn, Z., Zettle, R. D., Rosenfarb, I. S., Cooper, L. D., & Grundt, A. M. (1999). The impact of acceptance versus control rationales on pain tolerance. The Psychological Record, 49, 33–47.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D., & McCurry, S. M. (2004). Measuring experiential avoidance: a preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 54, 553–578.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). New York: The Guildford Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: The program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York: Dell Publishing.

Keogh, E., Bond, F. W., Hanmer, R., & Tilston, J. (2005). Comparing acceptance and control-based coping instructions on the cold-pressor pain experiences of healthy men and women. European Journal of Pain, 9, 591–598. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.005.

Kingston, J., Chadwick, P., Meron, D., & Skinner, T. C. (2007). A pilot randomized control trial investigating the effect of mindfulness practice on pain tolerance, psychological well-being, and physiological activity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62, 297–300. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.007.

LeResche, L. (2000). Epidemiologic perspective on sex differences in pain. In R. Fillingim (Ed.), Sex, gender, and pain: Progress in pain research and management (pp. 233–249). Seattle: IASP Press.

Masedo, A. I., & Esteve, M. R. (2007). Effects of suppression, acceptance and spontaneous coping on pain tolerance, pain intensity and distress. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 199–209. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.006.

McCraken, L. M., MacKichan, F., & Eccleston, C. (2007). Contextual cognitive-behavioural therapy for severely disabled chronic pain sufferers: effectiveness and clinically significant change. European Journal of Pain, 11, 314–322. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2006-.05.004.

McCraken, L. M., Vowles, K. E., & Eccleston, C. (2005). Acceptance-based treatment for persons with complex, long standing chronic pain: a preliminary analysis of treatment outcome in comparison to a waiting phase. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 1335–1346. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.003.

Mikulas, W. L. (2011). Mindfulness: significant common confusions. Mindfulness, 2, 1–7. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0036-z.

Morone, N. E., Greco, C. M., & Weiner, D. K. (2008). Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: a randomized controlled pilot study. Pain, 134, 310–319. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.038.

Paez-Blarrina, M., Luciano, C., Gutierrez-Martinez, O., Valdivia, S., Ortega, J., & Rodriguez-Valverde, M. (2008). The role of values with personal examples in altering the functions of pain: comparison between acceptance-based and cognitive-control-based protocols. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 84–97. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.008.

Roche, B., Forsyth, J. P., & Maher, E. (2007). The impact of demand characteristics on brief acceptance and control-based interventions for pain tolerance. Cognitive and Behavioural Practice, 14, 381–393.

Rosenstiel, A. K., & Keefe, F. J. (1983). The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain, 17, 33–44.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guildford Press.

Takahashi, M., Muto, T., Tada, M., & Sugiyama, M. (2002). Acceptance rationale and increasing pain tolerance: acceptance-based and FEAR-based practice. Japanese Journal of Behavior Therapy, 28(1), 35–46.

von Baeyer, C. L., Piira, T., Chambers, C. T., Trapanotto, M., & Zeltzer, L. K. (2005). Guidelines for the cold pressor task as an experimental pain stimulus for use with children. The Journal of Pain, 6(4), 218–227. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.349.

Wicksell, R. K., Ahlqvist, J., Bring, A., Melin, L., & Olsson, G. L. (2008a). Can exposure and acceptance strategies improve functioning and life satisfaction in people with chronic pain and whiplash-associated disorders (wad)? A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 37(3), 169–182. doi:10.1080/16506070802078970.

Wicksell, R. K., Melin, L., Lekander, M., & Olsson, G. L. (2008b). Evaluating the effectiveness of exposure and acceptance strategies to improve functioning and quality of life in longstanding pediatric pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain, 141(3), 248–257. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.006.

Zeidan, F., Gordon, N. S., Merchant, J., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). The effects of brief mindfulness meditation training on experimentally induced pain. The Journal of Pain, 11(3), 199–209.

Zettle, R. D., Hocker, T. R., Mick, K. A., Scofield, B. E., Peterson, C. L., Song, H., & Sudarijanto, R. P. (2005). Differential strategies in coping with pain as a function of level of experiential avoidance. The Psychological Record, 55, 511–524.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendixes

Appendixes

Appendix 1: Acceptance Rationale

When we are in pain, there are a number of different ways in which we can think about it. One way of thinking about pain is to accept that we are in pain. Here is an example of an “acceptance” way of thinking about pain: I try to accept that I am in pain. I do this by disconnecting my evaluations about the pain from the pain itself. For example, if I have a thought like, “I can’t stand this pain,” I can accept that thought and notice that this is a thought that doesn’t need to prevent me from continuing on. If instead I try and control my thoughts by imagining that the pain isn’t there, I find that I end up thinking about my pain even more. When I accept thoughts, I can notice them, but I don’t allow them to control my behavior. I accept my thoughts and my feelings as they are, without trying to control them or without trying to push them away. I can stop trying to control the pain since this may be unproductive; instead, I try not to ignore my pain, and I don’t try to push thoughts away. I try to accept that the pain doesn’t mean I can’t continue on. What I need to do is accept my thoughts as they are.

Acceptance Instructions for the Pain Task

Thoughts and feelings do not cause you to do things. Therefore, if you have thoughts such as “I can’t stand this pain,” you do not have to let the thought control your actions. So, you are able to feel pain and still keep your hands in the cold water.

Appendix 2: Mindfulness Rationale

This exercise is called “awareness of breathing.” The exercise is brief and is an introduction to mindfulness practice. First, close your eyes, and let your awareness shift to your body in the chair. Now I would like you to focus your attention on your breathing. First of all, allow your attention to notice a deep slow breath, in and out. And again take a deep slow breath in and out, and on your next breath, pay attention to the feeling of the air coming into your body through your nostrils. Just feel the sensation of the air coming in and then going out of your body, and notice if you can, the movement of your belly as you breathe, and notice the movement of your ribs as you inhale and exhale. Notice which parts of your body move as you breathe. So as you sit there, continue to breathe in and out and let your awareness rest on this process of breathing in and breathing out. Keep your awareness on the sensations and feelings of just breathing. And as you continue to notice the breathing, notice any physical sensations in your body. See if you can notice the physical sensations of your body in the chair and your feet on the floor. Now, bringing your awareness again back to your breathing, see if you can follow the air as it goes all the way in through your nostrils down into your lungs. Notice the rise and fall of your stomach, the expanding and collapsing of your ribs, and any other movement in your body as you breathe. And if your mind has anything to say about this process, if it wants to draw you away to thinking about other things, just acknowledge your mind for that and bring your attention back to your breathing. Every time your mind runs away to thinking about other things, just simply bring your attention back to your breathing; there’s no need to force it. Just gently bring your attention back each time to your breathing. Now with mindfulness practice, you can choose to use mindfulness breathing by bringing your awareness to your breathing at any time.

Mindfulness Instructions for the Pain Task

In the cold pressor task that you’ve been doing, you can choose to use mindfulness of your breath to bring your attention to your breathing as you perform the task.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forsyth, L., Hayes, L.L. The Effects of Acceptance of Thoughts, Mindful Awareness of Breathing, and Spontaneous Coping on an Experimentally Induced Pain Task. Psychol Rec 64, 447–455 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-014-0010-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-014-0010-6