Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to investigate the factors associated with HPV awareness among women aged 16 to 64 years, among underserved minority Hispanic women living in Puerto Rico.

Methods

A population-based, cross-sectional sample of 566 women, ages 16 to 64 years, living in the San Juan metropolitan area were surveyed regarding sexual behavior, HPV knowledge, and HPV vaccine uptake. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Overall, 64.8 % of the women in the sample had heard about the HPV vaccine. Among those in the recommended catch-up vaccination age range (16–26 years, n = 86), 4.7 % had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine. Of those aware of the availability of the HPV vaccine, most had learned about it through the media, whereas, only 39.6 % had learned about it from a physician. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that HPV awareness (OR 8.6; 95 % CI 5.0–14.8) and having had an abnormal Pap smear (OR 2.0; 95 % CI 1.2–3.4) were associated with HPV vaccine awareness (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

HPV vaccine awareness among Hispanic women in the San Juan metropolitan area of Puerto Rico continues to be low. Strong recommendations from physicians and participation in HPV vaccine educational efforts are essential if the rate of HPV vaccination is to increase in the targeted population. Compared to the USA, and to their US Hispanic counterparts, a health disparity with regard to HPV vaccine awareness and coverage is evident in Puerto Rico; targeted action to deal with this disparity is urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the USA and is considered the second most important infectious agent related to cancer; it has been proven to be associated with cervical cancer; cancer of the oropharynx, anus, vagina, vulva, and penis; and genital warts [1–4]. Three HPV vaccines are currently available in the USA. HPV4 (quadrivalent vaccine) contains non-infectious protein antigens for HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 and is approved for males and females aged 9 to 26 years. In females, this vaccine prevents premalignant and malignant conditions of the cervix, vulva, and vagina, and in both males and females, it prevents anal cancer and genital warts. The HPV2 vaccine (bivalent vaccine) protects against HPV types 16 and 18 and is approved for females aged 10 to 25 years for the prevention of premalignant conditions and adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix [5]. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routine vaccination with HPV4 or HPV2 for females aged 11 to 12 years and with HPV4 for males aged 11 to 12 years. HPV vaccination is also recommended for females aged 13 through 26 years, males aged 13 through 21 years, men who have sex with men, and immunocompromised persons, including those with HIV infection, who have not been previously vaccinated. Males aged 22 through 26 years may also be vaccinated [6, 7].

In December 2014, the Food and Drug Administration approved a nine-valent HPV vaccine (HVP9) to be used in females aged 9 to 26 years and males aged 9 to 15 years [8]. The new vaccine is expected to substitute HPV4 and has also been included by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the immunization schedule [9]. The HPV9 targets five additional strains of HPV (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and thus adds additional protection for other cancer and genital wart-related types [10].

According to the President’s Cancer Panel, the uptake of the HPV vaccine in the USA has fallen short of the target levels established by Healthy People 2020, which had as a goal the achievement of vaccinating (with the complete regimen of 3 doses) 80 % of all 13- to 15-year-old girls in the USA. Thus, the Cancer Panel urges that HPV vaccine uptake in the USA be accelerated by (1) reducing missed clinical opportunities to recommend and administer vaccines, (2) increasing parents’, caregivers’, and adolescents’ acceptance of HPV vaccines, (3) maximizing access to HPV vaccination services, (4) promoting global vaccine uptake, and (5) continuing the research needed to improve both HPV vaccines and vaccine uptake [11]. These initiatives are of great importance, as HPV vaccination can lead to substantial reductions in the incidence of HPV infection and HPV-related diseases [12].

Although previous data had shown a low utilization of the HPV vaccine among minority populations and individuals living in poverty [13–15], recent CDC data show that Hispanic (45 %) and Asian (43 %) girls aged 13 to 17 years are more likely to complete the HPV vaccination regimen (three doses) than are non-Hispanic white (35 %) and African-American (34 %) girls; those girls living below poverty levels are also more likely to get vaccinated than their non-poverty-stricken counterparts [16]. Although the reasons for these racial discrepancies regarding vaccination are not clear, they may be related to variability in access to care, cultural influences, or patient–provider communication barriers [17]. Also, programs such as Vaccine for Children may have contributed to the relatively higher vaccination coverage that is seen in low-income groups. Other studies have found that Hispanic women have low levels of HPV knowledge and HPV vaccine awareness and low HPV vaccination rates compared to non-Hispanic women in the USA [15, 18–20]. Meanwhile, data from the US 2010 National Health Interview Survey show that non-Hispanic whites, English-speaking parents, individuals born in the US, and individuals from relatively higher income families were more likely to be aware of the HPV vaccine [21]. Hispanics also showed lower HPV vaccine awareness in the National Cancer Institute’s 2013 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS; N = 3,185). Other factors associated to HPV vaccine awareness in their study included age, education, and income status [22].

This discrepancy in HPV knowledge and HPV vaccine awareness is of concern because there is a positive association between HPV awareness and cervical cancer prevention [17]. Given the high burden of cervical cancer in minority populations, it is important to understand the disparities in HPV vaccine awareness and vaccine uptake in order to improve preventive strategies for HPV infection [15, 23, 24].

It is also important to discern the differences in health care disparities among minority populations in recommending these strategies—here, Puerto Rican islanders as a subgroup of Hispanics [25]. Hispanics make up 16.3 % of the US population; however, Puerto Ricans make up 63 % of the overall Hispanic population in the USA and 99 % of the population on the island of Puerto Rico [26]. Household and personal income are markedly lower for Puerto Rican islanders compared to those who live on the mainland and are more likely to be living in poverty [27]. It is known that Hispanics in general use less healthcare than their non-Hispanic white counterparts, there exists “considerable variation in the use of healthcare services among Hispanic subgroups”—including those of Puerto Rican heritage [26]. Of interest for this study on HPV vaccination is that mainland Puerto Ricans were two times more likely to be vaccinated against influenza and pneumonia than their island counterparts [28].

In Puerto Rico, an admixed Hispanic population suffers from multiple social and HPV-related health disparities, which include higher rates of penile, oropharyngeal, and cervical cancer than are found in non-Hispanic whites in the USA [29]. These patterns are consistent with data on cervical cancer in the USA, where Hispanics have a higher incidence and death rate from cervical cancer [30]. Cervical cancer is the sixth leading type of cancer among women in Puerto Rico, representing 3.8 % of all female cancers diagnosed from 2005 to 2009, compared with the 3 % incidence of cervical cancer in Hispanics living in the USA during that same period [31–33]. In addition, HPV-related cancers were responsible for 7.5 % of the total costs (close to 5 million dollars) of loss of productivity due to cancer in Puerto Rico in 2004 [33] Recent data show an increase in the incidence (annual percent change of 4.5 %) of cervical cancer from 2004 to 2009 [34]. Moreover, the HPV vaccination rate in this population is 17 %, compared to the 37.6 % rate prevalent in the USA [unpublished data from the Puerto Rico Immunization Registry (PRIR); March 6, 2015] and Puerto Rican Hispanics whose rates of HVP vaccine initiation (51 %) and completion (21 %) are lower among girls aged 11 to 18 years in Puerto Rico compared with young Hispanic women in the US mainland (62.9 % initiating and 59.3 % completing the series) [35].

The objective of this study was to investigate the factors associated with HPV awareness among women aged 16 to 64 years and describe the reasons for non-vaccination among those age-eligible for the HPV vaccine (16 to 26 years) among a population-based sample of Hispanic women in Puerto Rico, an underserved minority, in order to understand which could hinder the Puerto Rico Department of Health in meeting federal guidelines in HPV vaccination efforts.

Methods

Study Population

Data from a population-based, cross-sectional study of HPV infection among women aged 16 to 64 years living in the San Juan metropolitan area of Puerto Rico (which includes the following seven municipalities: Carolina, Trujillo Alto, San Juan, Guaynabo, Bayamón, Toa Baja, and Cataño) were analyzed. The study procedures have been described in detail elsewhere [36]. In brief, the data were collected from December 2010 through April 2013, through a cluster probability sampling design consisting of four stages that sampled households in the San Juan metropolitan area (as described above) of Puerto Rico. In the first stage, a random selection of 50-block groups was done using a systematic design of originally 829-block groups, arranged by block mean property value (<$50,000 and ≥$50,000) per block. In the second stage, a single block was randomly selected from each block group, and the number of households was determined. In stage 3, each of the selected blocks was divided into segments of 12 to 16 consecutive homes, from which one home per group was randomly selected. Finally, in stage 4, one eligible female from each of the selected homes was randomly selected for the interview process, controlling for the desired number of participants by established age groups (16–34, 35–49, and 50–64 years). Women were eligible to participate in the study if they were aged from 16 to 64 years, were residents of the San Juan metropolitan area, were sexually active, and were not pregnant. Women who were HIV positive and cognitively or physically impaired were deemed ineligible. A total of 566 women were recruited for this study, equaling a response rate of 83.4 %.

Data collection was accomplished via face-to-face interviews and computer-assisted self-interviews, which latter made use of the audio-CASI (ACASI) system. The face-to-face interview collected information on demographics, reproductive history, lifestyle practices, and HPV knowledge, among other relevant covariates. Information on sexual behavior, condom-use practices, and drug use was collected using the ACASI system. Informed consent was obtained from participants prior to their participation. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus approved this study (A1810610).

Study Variables

The outcome variable of interest for this analysis was HPV vaccine awareness. HPV vaccine awareness was elicited with the following question (translated from Spanish): “Before today, had you heard about the cervical cancer vaccine or HPV vaccine?” In addition, women were asked about their vaccination status and attitudes towards vaccination with the following (translated) questions: “Have you been vaccinated with the HPV vaccine?” How many doses have you received?” and “Would you consider vaccination if your doctor recommended it?”

Covariates of interest included sociodemographic characteristics, such as age in years, birthplace, number of years of education, annual household income, and health care coverage. Lifestyle characteristics included age at first sexual encounter (<15 years, ≥15 years), number of sexual partners (1, 2–9, 10+), smoking habits (never/past/current), and alcohol use (never/past/current). Clinical characteristics included self-reported HPV vaccination, number of HPV vaccine doses received, and history of abnormal Pap smear (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population and variables of interest. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the associations of sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors with HPV vaccine awareness. Factors significantly associated with HPV awareness in the bivariate analyses (p < 0.05) were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. Within the multivariate model, the likelihood ratio test was used to assess the presence of interactions among variables, doing so by comparing the model with all the interaction terms to the model without such interaction terms. Interactions evaluated included those variables that were significantly associated with HPV awareness in the bivariate analysis as a way to explore potential effect modifiers.

Results

Study Population

A total of 566 females aged 16 to 64 were enrolled in the study. The mean age of the participants was 42.2 (±13.2) years; 16.1 % had less than a high school education, and 9.3 % had no health care coverage. Overall, 88.7 % had been born in Puerto Rico and 8.8 % in the Dominican Republic (Table 1).

Lifestyle and HPV Vaccination and HPV Vaccination Awareness Status

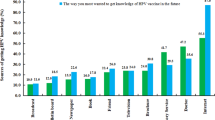

Over 14.5 % of the participants reported their first sexual intercourse as having occurred before the age of 15 years, 16.9 % had 10 or more lifetime sexual partners, and 21.6 % had a history of abnormal Pap test results (Table 2). Although 81.8 % of the participants knew about HPV, only 64.8 % were aware of the vaccine’s availability (Table 3). Of 86 women in the recommended catch-up vaccination age range (16–26 years), 4.7 % had received at least one dose of the vaccine; only one (1.2 %) had received all three doses. Among women who were aware of the vaccine (n = 366), only 39.6 % said they had learned about it from a physician (Fig. 1). The most frequently reported sources of information were the different mass media: TV advertisements (69.4 %), newspapers or magazines (40.2 %), TV news (34.2 %), and TV programs (34.7 %).

Among women who were aware of the HPV vaccine and within the recommended vaccination age-range (16–26 years) (n = 54, 62.7 %), the most commonly reported reasons for not being vaccinated included a lack of knowledge about the HPV vaccine (38.8 %), the perception of not being at risk (18.4 %), concerns about secondary side effects (32.7 %), and the lack of a physician’s recommendation (12.2 %) (Fig. 2). These results are similar in the 16–64 age group (n = 358) which included lack of knowledge about the HPV vaccine (31.3 %), identified perception that they were not at risk (23.2 %), concerns about secondary side-effects (17.0 %), and lack of physician recommendation (19.0 %). However, both groups identified they would consider vaccination if their physician recommended it (92.9 vs. 93.0 %).

Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Awareness

Age, number of years of education, annual family income, age at first sexual intercourse, smoking status, HPV awareness, and a history of abnormal Pap smear were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with HPV vaccine awareness in bivariate analysis (Table 3). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that HPV awareness (OR 8.6; 95 % CI 5.0–14.8) and a history of abnormal Pap smear (OR 2.0; 95 % CI 1.2–3.4) were positively associated with HPV vaccine awareness. Meanwhile, women aged 50 to 64 were less likely to be aware of the HPV vaccine (OR 0.6; 95 % CI 0.3–0.9) than were those aged 16 to 34 years. Annual family income was found to be important in HPV vaccine awareness, this variable was not included in the multivariate analysis because of the large percentage of missing data and the considerable number of missing values for non-response that were obtained from the participants, and given its correlation with educational attainment (Table 3). No interaction terms were found in the model (p = 0.41) when considering age, educational level, age at first sexual intercourse, smoking habits, HPV awareness, and history of abnormal Pap smear.

Discussion

The low rate of vaccination among women in this study is consistent with the data from the Puerto Rico Immunization Registry and the Department of Health showing that in 2010 and 2013, only 36 and 27 %, respectively, of girls aged 13 to 15 years had completed the HPV vaccine regimen (three doses) [14], which percentages are well below the target levels of Healthy People 2020 (80 %). Vaccination rates in Puerto Rico among teenagers (30 % in 2010 and 31 % in 2013) have not increased in the past years and are also lower than those reported in the NIS-Teen survey conducted on the US mainland (13–17 year olds). This survey shows that the vaccination coverage (comprising at least three doses of any HPV vaccine) for adolescent girls was 32 % in 2010 and 37.6 % in 2013, with 57.3 % receiving 1 or fewer doses in 2013 [14, 16].

In an island-wide cross-sectional study of students in the 7th to 12th grades conducted by Moscoso-Alvarez et al., it was found that only 58.2 % of students knew about HPV, only 56.9 % knew about the HPV vaccine, and only 18.8 % had been vaccinated against the virus [37].

NIS-Teen had previously found discrepancies in HPV vaccine uptake among racial minorities [15]. NIS-Teen 2013 coverage rates were higher for Hispanics than they were for whites, and three-dose series completion was similar between white and Hispanic girls [16]. This survey includes teens from all the states in the USA but excludes those living in Puerto Rico. Meanwhile, among adults in 2012, 34.5 % of women aged 19 to 26 years reported having received less than one dose of HPV vaccine, an increase of 5 % from 2011. In this group of women, only 18.7 % of Hispanics, compared to 42.2 % of whites, were vaccinated. The CDC also reported that racial/ethnic gaps persist in the receipt of all vaccines recommended for adults, with higher coverage for whites than for other groups. In 2010, the CDC reported a 15.1 % vaccination rate among Hispanics; in 2012 that rate increased to 18.7 % [38]. This is similar to the results reported by the Immunization Registry of Puerto Rico, which reported that in 2010, only 7 % of females in the catch-up vaccination age range of 16 to 26 had been vaccinated, while in 2013, 18 % of the females in that age group had received the three doses [unpublished data from the Puerto Rico Immunization Registry (PRIR); March 6, 2015].

Williams et al. found that women aged 18 to 26 years who were born outside of the USA and had lived in the USA for fewer than 10 years (immigrants) were less likely to have had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine (9.9 %) than were women born in the USA (24.4 %) and than those women who had lived in the USA for more than 10 years (19.4 %) [15]. Gelman et al. found that there were significant racial/ethnic disparities in HPV vaccination when US-born Hispanics, foreign-born Hispanics, and African-Americans were compared to whites [20]. Since Puerto Ricans are considered foreign-born Hispanics within the USA, this correlates with our findings of low HPV vaccine uptake on the island.

Minority status can be an obstacle for HPV awareness and HPV vaccination because of problems with communication [15, 20]. In this study, 81.8 % of women were aware of HPV, while 64.8 % were aware of vaccine availability. The lack of awareness in our study is comparable with findings reported by Morales-Campos et al. who reported that though many Hispanic mothers and girls had heard of the HPV vaccine, they had limited knowledge and many misconceptions about it [38]. Other studies, including systematic reviews, found an association between ethnicity and lower levels of HPV vaccine awareness [39–42]. Holman DM, in a systematic review, identified access to the vaccine and both the lack of knowledge and misconceptions about the HPV vaccination among parents as being important barriers against vaccination [40]. In order to increase HPV vaccine awareness and break the barriers to and the misconceptions about HPV vaccination in these communities, better educational efforts need to be made [37, 40, 41]. Potential educational strategies include educating parents regarding the importance of being vaccinated at the target age (11–12 years) and informing them of the recommended catch-up age; in addition, sexual education that promotes HPV awareness and vaccination should be implemented in the public and private school systems [42]. This is particularly important since it has been found that a majority of females will become infected with HPV within 2 to 3 years of sexual activity onset [11]. Our study ascertained that women aged 50 to 64 years had lower awareness than did those aged 16 to 34, while no significant differences in vaccine awareness were observed between those aged 34 to 49 and those who were younger (16–34 years). This reduced awareness of the HPV vaccine in the older cohort may be related to the fact that these women may be less likely to have younger kids, and women with children of this general age are more likely to receive information about this topic. HPV awareness and having a history of an abnormal Pap smear were also positively associated with HPV vaccine awareness in our study. This correlates with the literature, which reports that having a Pap smear within the previous 12 months to being surveyed was found to be positively associated (p < 0.05) with the awareness of the HPV vaccine [20]. Moreover, abnormal Pap smear results or a history of having HPV might be associated with HPV awareness [20, 40, 43]. A patient with an abnormal Pap smear or who has a history of HPV may end up being an opportunity for a physician, in that physician will be able to provide the patient with relevant information; it could be an opportunity, as well, for that patient, encouraging her to research the topic. It is important for women to understand the link between HPV and cervical cancer since this understanding will help them to make appropriate, evidence-based choices from among the existing prevention strategies, which include cervical cytology, HPV DNA testing, and HPV vaccination, as recommended [43].

Consistent with previous studies nationwide, most of the women (93 %) who had not received the HPV vaccine indicated that they would seek vaccination if their physician recommended their doing so [44–46]. Meanwhile, only 39.6 % of women who were aware of the vaccine had become so through their physicians. This is an important finding, as physician recommendation was found to increase adolescent HPV vaccination fivefold in a study conducted using the 2009 National Immunization Survey [14]. In a study published in 2013, physician recommendation was found among the predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among daughters of low-income Latina mothers [44]. Physician recommendation is an important factor in increasing HPV vaccination rates; effective educational programs for physicians need to be developed in Puerto Rico and the USA in order to be able to increase these rates. According to a report from the CDC, if the HPV vaccine were to have been administered during health care visits at which another vaccine was administered, vaccination initiation could have reached 92.6 % [16]. According to the President’s Cancer Panel, and supported by our results, missed clinical opportunities are the most important factor in the USA not having achieved high rates of HPV vaccine uptake [11].

While close to 40 % of the women in our study had heard of the HPV vaccine from a physician, this contrasts with the fact that most had become aware of the vaccine through such media as TV advertisements (69.4 %), newspapers and magazines (40.2 %), TV programs (34.7 %), and the TV news (34.2 %), which fact also establishes the importance of media in terms of public education. A study by Almeida et al. reported that Hispanics have less HPV awareness than do non-Hispanic whites (29 vs. 52.4 %) and that their sources of information are advertisements (34 %), health professionals (29 %), and the media (19 %) [46]. This correlates with our findings that patients learn about HPV most commonly from advertisements. Since physicians should be the key players in the divulging of the knowledge that the population has on the subject, it is important to develop a strategic plan on its delivery to vaccine-eligible patients and the parents of those patients.

In our study, the most common reasons for non-vaccination among those within the recommended vaccination age of the vaccine were lack of knowledge (38.8 %), not considering themselves to be at risk (18.4 %), lack of physician recommendation (32.7 %), and concern about side effects (12.2 %). These findings are similar to those found in a nationwide study of mothers of adolescent females; this study found that the top three reasons for non-vaccination were concern about vaccine side effects (36.0 %), concern about danger to daughter (36.0 %), and provider non-recommendation (34.4 %) [17]. Another study, this one evaluating the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HPV vaccination among Puerto Rican mothers and their daughters, found the following to be associated with low vaccine uptake: incomplete knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine; inconsistent beliefs regarding susceptibility to HPV infection and cervical cancer; concerns about vaccine effectiveness, safety, and side effects; concerns that the vaccine might promote sexual dis-inhibition; and the overall cost of the vaccine [47]. In terms of promoting vaccination, these findings, in addition to what has been set forth by the President’s Cancer Panel, confirm the importance of physician recommendation as well as patient education on the risks of contracting HPV and the side effects of the vaccine, among other topics [11].

The strengths of our study are the inclusion of a probabilistic sample of females, which enhances the generalizability of the findings in the San Juan metropolitan area of Puerto Rico, and an adequate response rate (83.4 %). However, there are several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow any inference to be drawn with respect to the causal relationship among variables. Second, the study sample is representative only of females living in the San Juan metropolitan area, and thus findings may not be generalizable to the female population of Puerto Rico as a whole. Third, although we used the audio-CASI system in the collection of sensitive information, this system requires some degree of self-reporting, meaning that clinical data and information regarding socio-demographic and lifestyles might be subject to information bias. Fourth, self-reported HPV vaccine uptake may result in a bias in the data and, moreover, in the underreporting of vaccination status. Furthermore, our study had insufficient sample size to appropriately evaluate factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 16 to 26 years.

Conclusion

HPV vaccine awareness and uptake among females living in the San Juan metropolitan area in Puerto Rico were both low from 2010 to 2013. Although the media has played an important part in educating the public regarding the HPV vaccine, other methods of education should be further developed and utilized in tandem with that represented by the media. A potential educational strategy is to provide sexual education classes in the public and private school systems, and by so doing, change the perception of HPV infection risk, which is important if the vaccine is to become fully accepted. It is also important to find ways to increase parents’ acceptance of the HPV vaccine, since ultimately they are the ones who will decide whether or not their (minor) children will be vaccinated at the recommended age. The President’s Cancer Panel encouraged physicians to reduce the number of missed clinical opportunities for recommending and administering vaccines. Given that physician recommendation tends to be an essential factor in a woman’s decision to vaccinate, physicians need to be instructed in how to better educate their patients and how, as well, to effectively follow the vaccination process of each patient.

References

Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297(8):813–9.

Steben M, Duarte-Franco E. Human papillomavirus infection: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(2 Suppl 1):S2-5. Review.

Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(12):3030–44.

Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(3):175–201. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs491.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Information Statement. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/hpv-gardasil.pdf. Accessed 20 March 2014.

Markowitz L, Dunne E, Saraiya M, Chesson HW, Curtis CR, Gee J, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization practices (ACIP). CDC Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR). 2014;63(RR-5):1–30.

Adams M, Jasani B, Fiander A. Human papillomavirus (HPV) prophylactic vaccination: challenges for public health and implications for screening. Vaccine. 2007;25(16):3007–13.

FDA News Release. FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV. December 10, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm426485.htm. Accessed 15 March 2015.

Markowitz L. “Overview of issues and considerations: HPV vaccination recommendation options.” Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices meeting Oct 30, 2014.http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-10/HPV-05-Markowitz.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2015.

The HPV Vaccine: Access and Use in the U.S. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-hpv-vaccine-access-and-use-in/. Accessed 15 March 2015.

Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake: Urgency for Action to Prevent Cancer. A Report to the President of the United States from the President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/PDF/PCP_Annual_Report_2012-2013.pdf, Accessed 15 March 2015.

Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER.Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine. Cent Dis Control Prev Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR) 2007: 56(RR02), 1–24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm. Date Last Accessed 15 March 2015.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2009. August 20, 2010:59(32):1019–1023. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5932a3.htm?s_cid=mm5923a3_e%0d%0a…

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). (2011). National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2010. August 26, 2011 : 60(33);1117-1123http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6033a1.htm Date Last Accessed 15 March 2015.

Williams WW, Lu P, Saraiya M, Yankey D, Dorrel C, Rodriguez JL, et al. Factors associated with human papillomavirus vaccination among young women in the United States. Vaccine. 2013;31:2937–46.

Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Jevarajah J, Singleton JA, Curtis CR, MacNeil J, Hariri S. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2013. CDC MMRW. July 25, 2014: 63(29);625–33. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6329.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2015.

Kester LM, Gregory D, Zimet J, Fortenberry D, Kahn JA, Shew ML. A national study of HPV vaccination of adolescent girls: rates, predictors, and reasons for non-vaccination. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(5):879–85. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1066-z.

Berenson AB, Male E, Lee TG, Barrett A, Sarpong KO, Rupp RE, et al. Assessing the need for and acceptability of a free-of-charge postpartum HPV vaccination program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3):213.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.036.

McDougall JA, Madeleine MM, Daling JR, Li CI. Racial and ethnic disparities in cervical cancer incidence rates in the United States, 1992–2003. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(10):1175–86.

Gelman A, Nikolajski C, Schwarz EB, Borrero S. Racial disparities in awareness of the human papillomavirus. J Womens Health. 2011;20(8):1165–73. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2617.

Wisk LE, Allchin A, Witt WP. Disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine awareness among U.S. parents of preadolescents and adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(2):117–22. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000086.

Blake KD, Ottenbacher AJ, Finney Rutten LJ, Grady MA, Kobrin SC, Jacobson RM, et al. Predictors of human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge in 2013: gaps and opportunities for targeted communication strategies. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):402–10. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.024.

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh CK, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer Disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78–93.

Tiro JA, Meissner HI, Kobrin S, Chollete V. What do women in the U.S. know about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(2):288–94.

Weinick RM, Jacobs EA, Stone LC, Ortega AN, Burstin H, Hispanic Healthcare Disparities. Challenging the myth of a monolithic Hispanic population. Med Care. 2004;42(4):313–20.

Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic Population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. C2010BR-04. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2015.

Pew Research Center 2014 Cohn D, Patten E, Hugo-Lopez M. Puerto Rican Population Declines on Island, Grows on U.S. Mainland. Pew Research Center. August 11, 2014. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2015.

Ho GYF, Quian H, Kim MY, Melnik TA, Tucker KL, Jimenez-Velazquez IZ, et al. Health disparities between island and mainland Puerto Ricans. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;19(5):331–9.

Colón-López V, Ortiz AP, Palefsky J. Burden of human papillomavirus infection and related comorbidities in men: implications for research, disease prevention and health promotion among Hispanic men. PR Health Sci J. 2010;29(3):232–40.

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(5):283–98. doi:10.3322/caac.21153.

Tortolero-Luna G, Zavala-Zegarra D, Pérez-Ríos N, Torres-Cintrón CR, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Traverso-Ortiz M, Román-Ruiz Y, Veguilla-Rosario I, Vázquez-Cubano N, Merced-Vélez MF, Ojeda-Reyes G, Hayes-Vélez FJ, Ramos-Cordero M, López-Rodríguez A, Pérez-Rosa N. Cancer in Puerto Rico, 2006–2010: Incidence and Mortality. Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry. San Juan, PR. 2013. http://biblioteca.uprh.edu/doc/Cancer-in-Puerto-Rico-2006-2010.pdf. Last Accessed 15 March 2015.

Ortiz AP, Soto-Salgado M, Calo WA, Tortolero-Luna G, Pérez CM, Romero CJ, Pérez J, Figueroa-Vallés N, Suárez E. Incidence and mortality rates of selected infection-related cancers in Puerto Rico and in the United States. Infect Agent Cancer. 2010;May 14;5:10.

Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Pérez-Irizarry J, Marín-Centeno H, Ortiz AP, Torres-Berrios N, et al. Productivity loss in Puerto Rico’s labor market due to cancer mortality. P R Health Sci J. 2010;3:241–9.

Traverso-Ortiz M. The rise of cervical cancer in Puerto Rico: Are policies effective? Presentation. North American Association of Central Cancan Registries Annual Conference. June 26, 2014.

Fernández ME, Le YL, Fernández-Espada N, Calo WA, Savas LS, Vélez C, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among Puerto Rican mothers and daughters, 2010: a qualitative study. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:140171. doi:10.5888/pcd11.140171.

Ortiz AP, Marrero E, Muñoz C, Pérez C.M, Tortolero-Luna G, Romaguera J, Suárez E. Methods in HPV surveillance: Experiences from a population-based study of HPV infection among women in the San Juan Metropolitan Area of Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. 2015:(In press).

Moscoso-Alvarez M, Rodriguez-Figueroa L, Ortiz AP, Reyes-Pulliza JC, Colon H. HPV vaccine knowledge and practice among adolescents in Puerto Rico. Oral Presentation. Am Publ Health Assoc Annu Meet. 2014.

Morales-Campos DY, Markham CM, Peskin MF, Fernandez ME. Hispanic mothers' and high school girls' perceptions of cervical cancer, human papilloma virus, and the human papilloma virus vaccine. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5 Suppl):S69–75. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.020.

Reimer RA, Schommer JA, Houlihan AE, Gerrard M. Ethnic and gender differences in HPV knowledge, awareness, and vaccine acceptability among White and Hispanic men and women. J Community Health. 2014;39(2):274–84. doi:10.1007/s10900-013-9773-y.

Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752.

Fu LY, Bonhomme LA, Cooper SC, Joseph JG, Zimet GD. Educational interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptance: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.091.

Hendry M, Lewis R, Clements A, Damery S, Wilkinson C. "HPV? Never heard of it!": a systematic review of girls' and parents' information needs, views and preferences about human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31(45):5152–67. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.091.

Waller J, McCaffery K, Forrest S, Szarewski A, Cadman L, Wardle J. Awareness of human papillomavirus among women attending a well woman clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(4):320–2.

Gerend MA, Zapata C, Reyes E. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among daughters of low-income Latina mothers: the role of acculturation. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(5):623–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.006.

Wong, Ker Y, and Young K Do. Are there socioeconomic disparities in women having discussions on human papillomavirus vaccine with health care providers? BMC Women's Health. 2012:12.33. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-12-33.

Almeida CM, Tiro JA, Rodriguez MA, Diamant AL. Evaluating associations between sources of information, knowledge of the human papillomavirus, and human papillomavirus vaccine uptake for adult women in California. Vaccine. 2012;30(19):3003–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.079.

Fernández ME, Le YL, Fernández-Espada N, Calo WA, Savas LS, Vélez C, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among Puerto Rican mothers and daughters, 2010: a qualitative study. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:140171.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant 1 SC2 AI090922-01) and by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (under award number 2U54MD007587) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (Institutional and National) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients who took part in the study.

Conflict of Interests

Romaguera J., Caballero-Varona D., Tortolero-Luna G., Marrero E., Suárez E., Pérez CM, Muñoz C., Ortiz AP, and Palefsky J. all declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the research reported in or publication of this paper.

Animal Studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romaguera, J., Caballero-Varona, D., Tortolero-Luna, G. et al. Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Awareness in a Population-Based Sample of Hispanic Women in Puerto Rico. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 3, 281–290 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0144-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0144-5