Abstract

This study aims to examine the factors associated with the level of HPV infection and HPV vaccine awareness among rural African Americans living in the Black Belt region of Alabama. A cross-sectional survey on cancer screening and health behaviors was conducted in the Black Belt region of Alabama. Adults (18 years or older) recruited through convenience sampling completed the self-administered survey. Binary logistic regressions were conducted to identify factors associated with HPV infection and HPV vaccine awareness among African American participants. Slightly more than half of the participants were aware of HPV (62.5%) and HPV vaccine (62.1%). Married or partnered participants had lower awareness of HPV or HPV vaccine. Family cancer history and self-reported health status were positively associated with both HPV and HPV vaccine awareness. In addition, employment was positively associated with HPV awareness, and participation in social groups was positively associated with HPV vaccine awareness. Tailored educational interventions that consider our findings might increase HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and contribute to better vaccine uptakes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection in the United States (US), with nearly 80 million individuals currently infected, and about 14 million new cases each year [1]. Although most HPV infections resolve themselves within 2 years, persistent high-risk HPV infection can cause cervical cancer, other anogenital cancers, and oropharyngeal cancer in both women and men, contributing to nearly 35,000 cancer cases annually [2]. First approved for use in the US in 2006, the HPV vaccine prevents more than 90% of HPV-attributable cancers [2]. However, 2019 data showed low vaccine uptake, with only 54% of adolescents (13–17 years old) [3] and only 21.5% of young adults (18–26 years old) completing recommended dosages [4]. Moreover, HPV vaccination among individuals in the southern US and those living in rural settings are even lower [3, 5, 6]. Hence, a deeper exploration of factors influencing HPV vaccine uptake in rural, southern areas is needed.

Previous studies indicate that awareness and knowledge of HPV and the HPV vaccine are associated with vaccine acceptance and uptake [7,8,9,10]. Recent data using a nationally representative sample found that only 66% of US adults had heard of HPV and the HPV vaccine [11]. Studies examining urban and rural differences have found that rural residents were less likely to be aware of HPV and HPV vaccine than urban counterparts [12, 13].

The literature also suggests that demographics and health-related factors influence HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge. For example, relevant socio-demographics associated with lower HPV and vaccine awareness/knowledge include being male, older age, unemployed, unskilled laborer, having lower educational attainment, low income, and not having children [11, 12, 14,15,16]. Moreover, many health indicators, such as better self-reported health status, having health insurance coverage, and a child having a primary care provider, have been associated with greater HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge [14, 15].

These factors warrant attention, especially for residents of Alabama, a Southern state with many rural areas, according to the Alabama Rural Health Association (2018). In health-related data, rural is defined as “all population, housing, and territory not included within a United States Census Bureau Alabama Urbanized Area of 50,000 or more people” [17]. Alabama has one of the highest rates of cervical cancer incidence in the US (9.6 vs. 8.0 per 100,000 nationally), with exceptionally high rates in the state’s “Black Belt” counties [18]. This region in Alabama is part of a national Black Belt region in the U.S, spanning from Texas to Virginia, named for the rich, fertile soil and subsequent agriculturally based economy [19]. Today, however, counties in Alabama’s Black Belt are also noted as very rural, with large proportions of African American residents and high socioeconomic and health disparities [20, 21]. Socioeconomic factors include high rates of poverty and unemployment, low education levels, and poor access to education [20,21,22]. Health indicators include poor overall health, no private or public health insurance, high rates of adverse health outcomes (e.g., stroke, chronic diseases), high cancer mortality rates, low HPV vaccine uptake, and low access to social services, education, and medical care [20,21,22,23]. These disparities are all common predictors of HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge [22, 23], suggesting Blackbelt residents may be at risk.

Although rural–urban differences in HPV and HPV vaccine awareness are reported, few studies have thoroughly examined the higher at-risk population or Southern rural African Americans. This study aims to examine HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and associated factors among rural, Southern African Americans. The findings will inform rural-specific approaches among similar at-risk populations and strategies to optimize HPV vaccination and prevent many HPV-associated cancers.

Methods

Data Collection

Self-administered surveys on cancer screening and health behavior were completed by participants in Livingston city and Selma city in Alabama. Livingston city is located in Sumter County, Alabama, and Selma City is located in Dallas County, Alabama. Sumter county and Dallas country are two of eighteen counties of the Black Belt Region of Alabama. A convenience sample strategy was applied during the data collection. Study eligible included African-American individuals aged 18 and older.. Two community liaisons who previously worked as health professionals in the targeted community led the data collection. The liaisons advertised the survey events using phone calls and emails. Surveys were read to participants with low literacy, and researchers recorded responses. Due to limited technology literacy among participants, paper surveys were used with subsequent data entry into Qualtrics. Participants received $15 for completing the survey. In total, 257 individuals completed the survey, and non-African American participants were excluded (N = 224). Written consent forms were obtained from all participants and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board from the first author’s institution (Protocol ID:18–045-1202).

Dependent Variables

The primary dependent variables were HPV and HPV vaccine awareness, measured by two yes-or-no questions in the survey: “Have you heard of HPV?” and “Have you heard of HPV vaccine?” (0 = no, yes = 1).

Independent Variables

Socio-demographics, perception of race affecting healthcare quality, healthcare resources, participation in social groups, and health-related factors were included as independent variables.

Socio-demographics

These variables included age (0 = 18–49 years old, 1 = 50 years old and over), gender (0 = male, 1 = female), marital status (0 = single, separated, widowed, or divorced, 1 = married or partnered), educational attainment (0 = below bachelor’s degree, 1 = bachelor’s degree or above), and employment status (0 = unemployed, 1 = employed), all of which were analyzed as dichotomous variables. Participants reported their annual household income range by selecting from the following options: 1 = $0–$9,999, 2 = $10,000–$14,999, 3 = $15,000–$19,999, 4 = $20,000–$34,999, 5 = $35,000–$49,999, 6 = $50,000–$74,999, 7 = more than $75,000. Income was analyzed as a continuous variable, ranging from 1 to 7.

Perception of Race Affecting Healthcare Quality

Participants were asked in the survey, “Do you think your race affects the quality of healthcare that you receive?” (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Healthcare Resources

Having a usual place for healthcare and having a primary physician were analyzed dichotomously (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Participation in Socializing Groups

Participants were asked if they participated in any socializing group, such as a club or religious group (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Health-Related Factors

Self-reported health status, family cancer history, and the number of medical conditions were included in health-related factors. Participants rated their current health with a single item that asked, “How would you rate your health at the present time?” Responses were “very poor,” “poor,” “fair,” “good,” and “excellent or very good.” The final variable was obtained by dichotomizing the original variable: 0 = very poor/poor/fair, 1 = good/excellent, or very good. For family cancer history, participants were asked, “Have any of your family (parents, grandparents, siblings, or close relatives) ever had cancer of any kind?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). Participants were also asked, “What types of disease do you suffer from, high blood pressure/diabetes/cardia disorder/stroke/arthritis/asthma and lung disease/gastrointestinal disorders?”. The number of diseases that participants reported was analyzed as a continuous variable, ranging from 0 to 7.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to describe the characteristics of independent variables and levels of HPV and HPV vaccine awareness. Bivariate analysis was employed to examine unadjusted associations between each independent variable and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine, respectively. Lastly, two sets of binary logistic regression were conducted to examine the adjusted relationship between HPV/HPV vaccine awareness and socio-demographic perception of race affecting healthcare quality, healthcare resources, participation in social groups, and health-related factors.

Results

Description of Independent Variables

As shown in Table 1, more than half of the participants were older than 50 (57.6%), three-quarters were female (73.7%), and around 37.9% were married or partnered. Only one-quarter of respondents had a bachelor’s degree or above (25.9%), and less than 35.7% of participants were employed. Participants tended to have low to moderate income (mean = 1.63, SD = 1.20, range = 01–7). Around 40% of respondents reported that their race affected the quality of healthcare they received (41.5%). The majority of participants had a usual place for healthcare (82.1%), had a primary physician (87.1%), and participated in a socializing group (79.1%). Almost three-quarters of participants reported having a family member who had cancer (74.5%) and reported their health status as good/very good/excellent (78.1). The average number of medical conditions among participants was 1.54 out of 6.

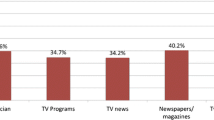

HPV and HPV Vaccine Awareness

In Table 1, participants reported moderate rates of awareness of HPV (62.5%) and HPV vaccine (62.1%). Gender, education, employment, primary physician, participation in socializing groups, family cancer history, and self-reported health status were significantly associated with both HPV and HPV vaccine awareness (p < 0.05). Additionally, the usual place for healthcare was significantly associated with awareness of HPV but not the HPV vaccine (p < 0.05).

Factors Associated with HPV and HPV Vaccine Awareness

Table 2 shows factors associated with HPV and HPV vaccine awareness, respectively. Marital status, family cancer history, and self-reported health status were significantly associated with both HPV and HPV vaccine awareness. Participants who were married or partnered were less likely to have heard of HPV (OR = 0.17, CI = 0.05–0.53, p < 0.05) or the HPV vaccine (OR = 0.17, CI = 0.06–0.53, p < 0.05). Participants who reported family cancer history were also more likely to be aware of HPV (OR = 3.14, CI = 1.01–9.80, p < 0.05) and the HPV vaccine (OR = 3.82, CI = 1.27–11.48, p < 0.05). Lastly, self-reported health status was also positively related to HPV awareness (OR = 5.58, CI = 1.86–16.78, p < 0.05) and HPV vaccine awareness (OR = 7.15, CI = 2.42–21.17, p < 0.05). Employment was only significantly associated with HPV awareness while participating in a socializing group only significantly predicted HPV vaccine awareness. Participants who were employed were more likely to be aware of HPV (OR = 4.10, CI = 1.15–14.56, p < 0.05), and participants who participated in socializing groups had a higher likelihood of hearing of HPV vaccine (OR = 3.40, CI = 1.29–8.94, p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study adds to the body of literature assessing HPV and HPV vaccine awareness among rural Southern African Americans and factors associated with awareness. Overall, respondents had low awareness of HPV (62.5%) and the HPV vaccine (62.1%)—both lower than national estimates (66% for both HPV and HPV vaccine awareness) [11]. As reported in previous studies, these findings highlight that the existing vulnerability of rural regions, such as lack of resources, poverty, and low education, influences low awareness of HPV [22, 23]. Age may have contributed to these results since the majority of participants were older than 50, and older age has been reported as a predictor of low awareness in previous studies [15, 16]. However, efforts to educate about HPV and the HPV vaccine, even among older populations, are needed to prevent many HPV-associated cancers. This knowledge could be passed down to younger generations to increase vaccine uptake at the recommended ages of 11–12 years old [1].

Our results report consistent predictors for HPV awareness and HPV vaccine awareness, although having a primary physician was only associated with greater HPV vaccine awareness. Consistent with previous research, marital, employment, health status, and primary physician existence, were associated with HPV awareness [14,15,16]. Our findings found that a lack of HPV and HPV vaccine awareness was associated with being married. Although previous literature does not provide an explanation for this finding, the reason may be that those who are married or partnered—with a stable sexual partner—are at lower risk of HPV infection and might not be the main target population for HPV education. Also, it has been only 15 years since the promotion for the prevention of HPV [2], suggesting a possible lack of awareness among individuals who are older and/or married. Higher awareness among employed individuals may be associated with having employer-provided health insurance, allowing affordable healthcare visits at which individuals can receive education from their providers. Our study found that better self-reported health status was associated with both HPV and HPV vaccine awareness. In contrast, studies documenting the relationship between self-reported health status and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine found that self-reported health status was positively associated with HPV knowledge among African Americans [24]. Health indicators suggest that distributing information via physicians is an effective educational method to the public, especially to rural residents who tend to have low healthcare resources.

Our study provides insight into other determinants of HPV awareness, such as social group participation and family cancer history, which implies that people who socialize might have greater awareness. Similarly, those with family cancer history may be more aware of cancer and other health issues and may also seek in-depth health information regarding prevention. These findings suggest that information can be easily distributed to a larger group once information is distributed to a single or small group.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. First, as a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be assumed. Second, the convenience sampling methodology limits the generalization of these findings to rural African Americans. Moreover, the data collection occurred at two community centers, which might not be able to reach all the rural population considering some rural residents might not have transportation to get to the community centers or are too isolated to get the notice. Third, our study assessed only HPV and HPV vaccine awareness by asking, “Have you heard of HPV/HPV vaccine?”. However, more specific knowledge on HPV and HPV vaccine remains unknown among the population, for example, knowledge on the relationship between HPV and cancer. Additionally, further studies are needed to explore more details on HPV knowledge among rural Southern African Americans.

Implications for Future Practice

Despite its limitations, our study suggests significant gaps regarding HPV and HPV vaccine awareness among rural, Southern residents and that the lack of awareness is associated with sociodemographic, health-related, and social factors. This is concerning as rural regions are particularly at risk for poor health outcomes and health disparities [23, 25], and educational interventions are warranted. Community-based education via providers or pharmacists on HPV and the HPV vaccine can help to increase HPV vaccination and ultimately decrease the incidence and mortality from HPV-associated cancers. The CDC and investigators with a specific focus on rurality have developed evidence-based guidelines to improve these outcomes [25,26,27,28,29], such as combining HPV vaccination with other routine vaccines and well visits, as well as training staff on patient communication.

Leveraging community resources to communicate about HPV and the HPV vaccine can also effectively empower resource-poor regions [25]. For example, our study suggests that local residents who participate in social groups or have a family cancer history may be utilized to deliver information about HPV and HPV vaccination. This is demonstrated in a study by Casillas et al. which found that individuals who discussed and shared information about the HPV vaccine with family members or friends were more likely to consider the vaccine as effective than those who discussed it with a medical professional [30]. Barriers regarding low access to healthcare providers in rural areas can be supplemented with pharmacist administration of vaccines to increase accessibility to and convenience of vaccination [26, 31,32,33,34]. However, potential barriers, such as poor communication with primary care providers and lack of insurance reimbursement, must be addressed to strengthen this strategy [26, 35].

Conclusion

Rural communities experience numerous health disparities, including low HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and uptake. As our findings and previous literature suggest, sociodemographic and health-related factors such as employment, marital status, health insurance, and family cancer history commonly predict awareness. Therefore, tailored educational interventions that consider common predictors of health disparities while involving community members as a resource can increase awareness and contribute to better vaccine uptakes and prevention of many HPV-associated cancers.

Data Availability

Data is available as requested to the first author.

Code Availability

Code is available as requested to the first author.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Human papillomavirus (HPV). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html. Published 2019. Accessed October 27, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Cancers caused by HPV are preventable. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/protecting-patients.html. Published 2020. Accessed October 27, 2020.

Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109.

Boersma P, Black LI. Human papillomavirus vaccination among adults aged 18–26, 2013–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(354):1–8.

Swiecki-Sikora AA-O, Henry KA, Kepka D. HPV vaccination coverage among US teens across the rural-urban continuum. J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):506–17.

Vielot NA, Butler AM, Brookhart MA, Becker-Dreps S, Smith JS. Patterns of use of human papillomavirus and other adolescent vaccines in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(3):281–7.

Beavis AL, Levinson KL. Preventing cervical cancer in the United States: barriers and resolutions for HPV vaccination. Front Oncol. 2016;6:19.

Hirth JM, Fuchs EL, Chang M, Fernandez ME, Berenson AB. Variations in reason for intention not to vaccinate across time, region, and by race/ethnicity, NIS-Teen (2008–2016). Vaccine. 2019;37(4):595–601.

Lee HY, Lee J, Henning-Smith C, Choi J. HPV literacy and its link to initiation and completion of HPV vaccine among young adults in Minnesota. Public Health. 2017;152:172–8.

Sonawane K, Zhu Y, Montealegre JR, et al. Parental intent to initiate and complete the human papillomavirus vaccine series in the USA: a nationwide, cross-sectional survey. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(9):e484–92.

Boakye EA, Tobo BB, Rojek RP, Mohammed KA, Geneus CJ, Osazuwa-Peters N. Approaching a decade since HPV vaccine licensure: racial and gender disparities in knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2713–22.

Blake KD, Ottenbacher AJ, Rutten LJF, et al. Predictors of human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge in 2013: gaps and opportunities for targeted communication strategies. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):402–10.

Mohammed KA, Subramaniam DS, Geneus CJ, et al. Rural-urban differences in human papillomavirus knowledge and awareness among US adults. Prev Med. 2018;109:39–43.

Kepka D, Bodson J, Lai D, et al. Diverse caregivers’ HPV vaccine-related awareness and knowledge. Ethn Health. 2021;26(6):811–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1562052.

Lee HY, Choi YJ, Yoon YJ, Oh J. HPV literacy: the role of english proficiency in Korean American immigrant women. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):E64–70. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.E64-E70.

McBride KR, Singh S. Predictors of adults’ knowledge and awareness of HPV, HPV-associated cancers, and the HPV vaccine: implications for health education. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(1):68–76.

Alabama Rural Health Association. Definition of rural Alabama. https://arhaonline.org/definition-of-rural-alabama/. Published 2018. Accessed December 17, 2020.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: cervical cancer. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html. Published 2020. Accessed October 27, 2020.

Alabama Black Belt Heritage Area. History and heritage overview. https://www.alblackbeltheritage.org/heritage. Published 2023. Accessed 7 Apr 2023.

Alabama Department of Public Health. Alabama health disparities stats report 2010. Office of minority health. https://www.adph.org/minorityhealth/assets/HealthDisparitiesStatusReport04082011.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed 7 Apr 2023.

Winemiller TL. Black belt region in Alabama. Encyclopedia of Alabama. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2458. Published 2019. Accessed 7 Apr 2023.

Sims A, Archie-Booker E, Waldrop RT, Claridy M, Gerbi G. Factors associated with human papillomavirus vaccination among women in the United States. ARC J Public Health Community Med. 2018;3(1):6–12.

Flannery K, Klasing A, Root B. It should not happen: Alabama’s failure to prevent cervical cancer death in the Black Belt. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/11/29/it-should-not-happen/alabamas-failure-prevent-cervical-cancer-death-black-belt. Published 2018. Accessed 27 Oct 2020.

Lee HY, Luo Y, Daniel C, Wang K, Ikenberg C. Is HPV vaccine awareness associated with HPV knowledge level? Findings from HINTS data across racial/ethnic groups in the US. Ethn Health. 2022;27(5):1166–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1850648.

Vanderpool RC, Stradtman LR, Brandt HM. Policy opportunities to increase HPV vaccination in rural communities. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1527–32.

Cartmell KB, Young-Pierce J, McGue S, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and potential strategies for increasing HPV vaccination: a statewide assessment to inform action. Papillomavirus Res. 2018;5:21–31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Five ways to boost your HPV vaccination rates. Center for Disease Controol and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/boosting-vacc-rates.html. Published 2019. Accessed October 29, 2020.

Dilley SE, Peral S, Straughn JM, Scarinci IC. The challenge of HPV vaccination uptake and opportunities for solutions: lessons learned from Alabama. Prev Med. 2018;113:124–31.

Gunn R, Ferrara LK, Dickinson C, et al. Human papillomavirus immunization in rural primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):377–85.

Casillas A, Singhal R, Tsui J, Glenn BA, Bastani R, Mangione CM. The impact of social communication on perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness in a low-income, minority population. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(4):495–501.

Cebollero J, Walton SM, Cavendish L, Quairoli K, Cwiak C, Kottke MJ. Evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccination after pharmacist-led intervention: a pilot project in an ambulatory clinic at a large academic urban medical Center. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(3):313–21.

Daniel CL, Wright AR. Increasing HPV vaccination in rural settings: the hidden potential of community pharmacies. J Rural Health. 2020;36(4):465–7.

Islam JY, Gruber JF, Kepka D, et al. Pharmacist insights into adolescent human papillomavirus vaccination provision in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1839–50.

Ryan G, Daly E, Askelson N, Pieper F, Seegmiller L, Allred T. Exploring opportunities to leverage pharmacists in rural areas to promote administration of human papillomavirus vaccine. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E23–E23.

Calo WA, Shah PD, Gilkey MB, et al. Implementing pharmacy-located HPV vaccination: findings from pilot projects in five U.S. states. Human Vacc Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1831–8.

Funding

This work was supported by the Endowed Academic Chair Research Fund from the University of Alabama School of Social Work awarded to the first author (Dr. Lee).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hee Yun Lee contributed to the conceptualization, and writing and reviewing the manuscript. Yan Luo contributed to the data analysis and writing the manuscript. Cho Rong Won contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript. Casey Daniel and Tamera Coyne-Beasley contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The data was collected by the first author and the data collection was approved by the Institutional Review Board from the first author’s institution (Protocol ID:18–045-1202).

Consent to Participate

Written consent forms were obtained by all participants.

Consent for Publication

Consent was obtained from the participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, H.Y., Luo, Y., Won, C.R. et al. HPV and HPV Vaccine Awareness Among African Americans in the Black Belt Region of Alabama. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 808–814 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01562-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01562-0