Abstract

The sectional curvature of the volume preserving diffeomorphism group of a Riemannian manifold M can give information about the stability of inviscid, incompressible fluid flows on M. We demonstrate that the submanifold of the volumorphism group of the solid flat torus generated by axisymmetric fluid flows with swirl, denoted by \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\), has positive sectional curvature in every section containing the field \(X = u(r)\partial _\theta \) iff \(\partial _r(ru^2)>0\). This is in sharp contrast to the situation on \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu }(M)\), where only Killing fields X have nonnegative sectional curvature in all sections containing it. We also show that this criterion guarantees the existence of conjugate points on \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) along the geodesic defined by X.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Let (M, g) be a Riemannian manifold of dimension at least two with Riemannian volume form \(\mu \). The configuration space for inviscid, incompressible fluid flows on M is the collection of smooth volume-preserving diffeomorphisms (volumorphisms) of M, denoted by \(\mathcal {D}_\mu (M)\). Arnold (2014) showed in 1966 that flows obeying the Euler equations for inviscid, incompressible fluid flow can formallyFootnote 1 be realized as geodesics on \(\mathcal {D}_\mu (M)\). Using this framework, questions of fluid mechanics can be re-phrased in terms of the Riemannian geometry of \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu }(M)\). An overview of this is given in Arnold and Khesin (1998) or more recently in Khesin et al. (2013). Of particular interest is the sectional curvature of \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu }(M)\). As in finite dimensional geometry, given two geodesics with varying initial velocities in a region of strictly positive (resp. negative) sectional curvature, the two geodesics will converge (resp. diverge) via the Rauch Comparison theorem. In terms of fluid mechanics, this corresponds to the Lagrangian stability (resp. instability) of the associated fluid flows.

Arnold showed that the sectional curvature K(X, Y) of the plane in \(T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu }(M)\) spanned by X and Y is often negative but occasionally positive. Rouchon (1992) sharpened this to show that if \(M\subset \mathbb {R}^3\), then \(K(X,Y)\ge 0\) for every \(Y\in T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu }(M)\) if and only if X is a Killing field (i.e., one for which the flow generates a family of isometries). This result was generalized by Misiołek (1993) and the second author (Preston 2002) for any manifold with \(\dim {M}\ge 2\). This gives the impression that, in general, \(D_\mu (M)\) will mostly be negatively curved. The question of when one can expect a divergence free vector field to give nonpositive sectional curvature remains open. However, the second author (Preston 2005) provided criteria for divergence free vector fields of the form \(X = u(r)\partial _\theta \) on the area-preserving diffeomorphism groups of a rotationally-symmetric surface for which the sectional curvature K(X, Y) is nonpositive for all Y.

Our goal in this paper is to extend the curvature computation to \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\), the group of volumorphisms commuting with the flow of a Killing field \(E\). In particular, we consider the solid flat torus, \(M= D^2\times S^1\), where \(D^2\) is the unit disk in \(\mathbb {R}^2\) and \(S^1\) is the unit circle, with cylindrical coordinates \((r,\theta ,z)\) for \(0\le r\le 1\) and \(\theta ,z\in [0,2\pi ]\). We may think of this more concretely as the subset of \(\mathbb {R}^3\) with the planes \(z=0\) and \(z=2\pi \) identified, where \(E = \partial _\theta \) is the field corresponding to rotation in the disc. Fluid flows on this manifold correspond to axisymmetric ideal flows with swirl on the solid infinite cylinder, which are \(2\pi \)-periodic in the z-direction. We consider steady fluid velocity fields of the form \(X = u(r)\partial _\theta \). The submanifold \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) is a totally geodesic submanifold of \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu }(M)\) (see Vizman (1999), as well as Haller et al. (2002); Modin et al. (2011) for the general situation in the smooth context, or see the preprint Ebin and Preston (2013) for the Sobolev diffeomorphism context), corresponding to the fact that an ideal fluid which is initially independent of \(\theta \) will always remain so. Hence we compute sectional curvatures K(X, Y) where \(Y\in T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) is divergence-free and axisymmetric, i.e., \([E,Y]=0\).

In Preston (2005) the second author effectively showed that when X was considered as an element of \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,F}(M)\) where \(F = \frac{\partial }{\partial z}\) (corresponding to considering X as a two-dimensional flow rather than a three-dimensional flow), the sectional curvature satisfied \(K(X,Y)\le 0\) for every \(Y\in T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,F}(M)\) regardless of u(r). By contrast we show here that if u satisfies the condition

then \(K(X,Y)> 0\) for every \(Y\in T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\). We will also show that \(\frac{d}{dr}\big ( ru(r)^2\big ) \ge 0\) implies that \(K(X,Y)\ge 0\). This does not contradict the result of Rouchon, since the proof of that result relies on being able to construct a divergence-free velocity field with small support which points in a given direction and is orthogonal to another direction, and there are not enough divergence-free vector fields in the axisymmetric case to accomplish this here.

The fact that the curvature is strictly positive in every section containing X makes it natural to ask whether there are conjugate points along every such corresponding geodesic. Unfortunately the Rauch comparison theorem cannot be used here, since \(\inf _{Y\in T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)} K(X,Y) = 0\) even if (1) holds. Nonetheless we can show that as long as

the geodesic formed by \(X = u(r)\partial _{\theta }\) has infinitely many monoconjugate points. It is easy to see that condition (1) implies (2). We do this by solving the Jacobi equation explicitly. As in Ebin et al. (2006), where the case \(u(r) \equiv 1\) was considered, we can prove that these monoconjugate points have an epiconjugate point as a limit point, so that the differential of the exponential map is not even weakly Fredholm.

2 The Formula for Curvature

We first compute the curvature of \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) by expanding in a Fourier series in z. Here all our vector fields and functions are smooth on the compact manifold M, so that convergence of the series will never be an issue, as in the original computations of Arnold (2014). If desired one could do the same computations in the Sobolev \(H^s\) context, with \(s>5/2\), and treat the curvature operator as a continuous linear operator in \(H^s\), as done by Misiołek (1993), but the final curvature formula is the same in either case. Our method here is similar to that of the second author in Preston (2005), where the computations were two-dimensional.

Notice first of all that any smooth vector field Y which is tangent to \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) at the identity must be divergence-free and must commute with \(E=\frac{\partial }{\partial \theta }\). Therefore we can write in the form

where \(f(0,z)=g(0,z) = 0\) and g(1, z) is constant in z (in order to be well-defined on the axis of symmetry and to have Y tangent to the boundary \(r=1\)). We think of the term \(-\frac{g_z}{r} \partial _r + \frac{g_r}{r} \partial _z\) as an analogue of the skew-gradient in two dimensions. We may express Y in a Fourier series in z as \( Y(r,z) = \sum _{n\in \mathbb {Z}} Y_n(r,z)\) where

On any Riemannian manifold (M, g) with volume form \(\mu \), a formula for the curvature tensor on \(\mathcal {D}_\mu (M)\) is given by

where P(X) is the projection onto the divergence-free part of X. Concretely, P(X) is obtained by solving the Neumann boundary value problem

for q and then setting \(P(X) = X - \nabla q\). The non-normalized sectional curvature is then given by

See Misiołek (1993) for the derivation of the formula we use here. Our goal now is to compute \(R(Y_n,X)X\), and to do this we first need to compute \(P(\nabla _{Y_n}X)\).

Lemma 1

Suppose \(Y_n\) is of the form (4) and \(X = u(r)\,\partial _{\theta }\) in cylindrical coordinates on M. Then the covariant derivative \(P(\nabla _{Y_n}X)\) in \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) is given by \( P(\nabla _{Y_0}X) = 0\) and

where

with

and

with \(I_0\) and \(K_0\) denoting the modified Bessel functions of the first and second kinds.

Proof

Consider the cases \(n=0\) and \(n\in \mathbb {N}\) separately. For \(n=0\) we have

and \(\nabla _{Y_0}X = -rf_0(r)u(r)\partial _r\).

This is also the gradient of a function, and thus \(P(\nabla _{Y_0}X) = 0.\)

Now for \(n\ne 0\),

The solution \(q_n(r)e^{inz}\) of

must satisfy the ordinary differential equation

The left side of this equation is a standard Bessel differential operator, and so the solution formula (7) is essentially just the variation of parameters formula together with an integration by parts since \(I_0\) and \(K_0\) solve the corresponding homogeneous equation. Here we can simply verify the solution: taking the derivative of \(q_n(r)\), we obtain

and since \(\zeta _n'(1)=J_n(1)=0\) we get the correct boundary condition. Furthermore we get

and with these formulas we easily check that \(q_n\) satisfies (10). \(\square \)

The projection \(P(\nabla _YX)\) is the most complicated part of the curvature formula (5) since \(P(\nabla _XX)=0\) for steady flows X. Hence Lemma 1 easily gives the following expression for the curvature tensor.

Proposition 2

Let \(M = D^2\times S^1\). Suppose that \(X\in T_{\text {id}}\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(M)\) is defined by \(X = u(r)\partial _\theta \), and let \(Y_n\) be of the form (4). Then the curvature tensor \(R(Y_n,X)X\) is given for \(n\ne 0\) by

where \(q_n\) is the solution of the ODE (10). For \(n=0\) we get \(R(Y_0,X)X=0\).

Proof

We compute using formula (5). First note that \(\nabla _X X = -ru^2\partial _r\), which is the gradient of a function. Thus \(P(\nabla _X X ) = 0\).

With the formula for the projection \(P(\nabla _{Y_n}X)\) from Lemma 1 in hand, we will get

for any nonzero integer n.

We also easily compute

So, R will be given by (12). \(\square \)

The sectional curvature can now be computed explicitly using Lemma 1 and Proposition 2; the formula simplifies substantially due to Bessel function identities.

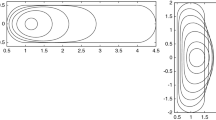

Theorem 3

On \(M=D^2\times S^1\) with \(X = u(r) \, \partial _{\theta }\) and Y expressed as in (3), the non-normalized sectional curvature is given by \( \overline{K}(X,Y) = \sum _{n\in \mathbb {Z}} \overline{K}(X,Y_n)\), where \(Y_n\) is expressed as in (4) and

Hence the curvature is positive for all Y if and only if \(\frac{d}{dr} \big (r u(r)^2\big ) > 0\).

Proof

Using formula (11) in (12), we obtain

which can clearly be expressed as \(e^{inz}\) times a function of r only. Orthogonality of the functions \(e^{imz}\) and \(e^{inz}\) over \(S^1\) when \(m\ne n\) implies that

The latter is now relatively easy to compute. We have

where \(\eta (r) = \frac{d}{dr} \big ( ru(r)^2\big )\). By the definitions (8) of \(H_n\) and \(J_n\), we see that the second term in (14) is

From here we adapt the corresponding computation in Preston (2006). Integrating by parts and using the fact that \(J_n(r)\overline{H_n}(r)\rightarrow 0\) as \(r\rightarrow 0\) or \(r\rightarrow 1\), we get

and another integration by parts (where again the boundary terms vanish) gives

Finally the Bessel function identity \(\frac{d}{dr} \left( \frac{K_1(r)}{I_1(r)}\right) = \frac{1}{r I_1(r)^2}\) implies (13). \(\square \)

Remark 4

The normalized sectional curvature is given by \( K(X,Y) = \frac{\overline{K}}{\langle \!\langle X,X\rangle \!\rangle \langle \!\langle Y,Y\rangle \!\rangle - \langle \!\langle X,Y\rangle \!\rangle ^2}\). Suppose that \(f=0\) and that only one \(g_n\) is nonzero in (4); then we have \(\langle \!\langle X,Y\rangle \!\rangle = 0\) and the sectional curvature takes the form

We can make this arbitrarily small by choosing a highly oscillatory \(g_n\). Hence although the curvature is strictly positive if \(\frac{d}{dr} \big (ru(r)^2\big ) > 0\), it cannot be bounded below by any positive constant.

3 Solution of the Jacobi Equation

It is natural to ask whether the positive curvature guaranteed by the theorem above ensures the existence of conjugate points along the corresponding geodesic. This is not automatic since although the sectional curvature is positive in all sections containing the geodesic’s tangent vector, it is not bounded below by any positive constant because of Remark 4; hence the Rauch comparison theorem cannot be applied directly (and in any case would need to be proved in the present formal context of weak metrics on Fréchet manifolds). In this section we answer this question affirmatively by solving the Jacobi equation more or less explicitly along such a geodesic, and show that in fact conjugate points occur rather frequently.

Theorem 5

Let \(\eta (t)\) be a geodesic on \(\mathcal {D}_{\mu ,E}(D^2\times S^1)\) with initial condition \(\eta (0)=\text{ id }\) and \(\dot{\eta }(0) = X = u(r)\partial _\theta \). Let \(\omega (r) = 2u(r) + ru'(r)\) denote the vorticity function of X, and assume that \(u(r)\omega (r)>0\) for all \(r\in [0,9]\). Then \(\eta (t)\) is a monoconjugate point to \(\eta (0)\) for every time \(t = 2 \pi \lambda /n\), where \(n\in \mathbb {N}\) is arbitrary and \(\lambda \) is any eigenvalue of the Bessel-type Sturm-Liouville problem

Proof

Along a geodesic \(\eta (t)\) with (steady) Eulerian velocity field X, the Jacobi equation for a Jacobi field \(J(t) = Y(t)\circ \eta (t)\) may be written (Preston 2002) as the system

where P is the orthogonal projection onto divergence-free vector fields. The first equation is the linearized flow equation, while the second is the linearized Euler equation used in stability analysis.

Write

where \(h=0\) on the axis \(r=0\) and h is constant on the boundary \(r=1\). Then it is easy to compute that (16) becomes the system

where \(\omega (r) = 2u(r) + r u'(r)\) is the vorticity defined by \({{\mathrm{curl}}}X = \omega (r) \, \partial _z\). Applying the curl to both sides of Eq. (18) to eliminate the projection operator, we obtain

Differentiating (19) in time and substituting (17) we obtain the single equation

Expand h in a Fourier series in z to get

Then for each n we can solve the eigenvalue problem

to make this look more familiar we set \(\phi (r) = r \psi (r)\) and obtain

which is a singular Sturm–Liouville problem analogous to the Bessel equation. We obtain a sequence of eigenfunctions \(\phi _{mn}(r)\) for \(m\in \mathbb {N}\), with eigenvalues \(C_{mn}\). We see that

so that if \(\omega (r)u(r)>0\), then C must be strictly negative; we write \(C = -\lambda _{mn}^2\) for the eigenfunction \(\phi _{mn}(r)\). Expanding \(h_n(t,r)\) in a basis of such eigenfunctions as

Equation (20) becomes

which obviously has solutions

for some coefficients \(a_{mn}\) and \(b_{mn}\).

Suppose \(a_{m,n}=a_{m,-n}=\tfrac{1}{2}\) for some (m, n) with \(n\ne 0\), and that all other a are zero and that every b is zero, so that \(h(t,r,z) = \cos {\left( \frac{nt}{\lambda _{mn}}\right) } \phi _{mn}(r) \cos {nz}\). Then by Eq. (19) we compute that

To find the Jacobi fields, write Y in Eq. (15) as

We easily compute that \(X = u(r) \, \frac{\partial }{\partial \theta }\) gives \([X,Y] = \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial g}{\partial z} u'(r) \, \frac{\partial }{\partial \theta }\), and thus Eq. (15) becomes in components

With \(g(0,r,z)=f(0,r,z)=0\), we find that

Thus both f and g vanish when \(t=0\) and when \(t = 2 \pi \lambda _{mn}/n\), so \(\eta (2\pi \lambda _{mn}/n)\) is monoconjugate to the identity along \(\eta \). \(\square \)

Remark 6

Using the Sturm comparison theorem we can estimate the spacing of the eigenvalues \(\lambda _{mn}\) and show that for fixed m the sequence \(\lambda _{mn}/n\) has a finite limit as \(n\rightarrow \infty \). Just as in Ebin et al. (2006), this must be an epiconjugate point. Therefore the differential of the exponential map is not even weakly Fredholm along any geodesic of this form (which is to say the differential of the exponential map, extended to a linear map in the weak Riemannian \(L^2\) topology, is not a Fredholm operator). It is worth noting that the reason the Jacobi equation is explicitly solvable in this case is because there is no “drift” term, so the total time derivative agrees with the partial time derivative, in the same way as in Ebin et al. (2006).

It would be very interesting to generalize the curvature computation to fields of the form \(X = u(r) \sin {z} \, \partial _{\theta }\), which is the initial velocity field of the Luo-Hou initial condition (Luo and Hou 2014) that leads numerically to a blowup solution. We expect that the formula \(\int \overline{H_n'}J_n - \overline{J_n'}H_n\) which appears both here and in Preston (2005) is a typical feature of curvature formulas when computed correctly, although they doubtless become substantially more complicated.

Notes

This was proved rigorously by Ebin and Marsden (1970), by working in the context of Sobolev \(H^s\) diffeomorphisms for \(s>\tfrac{1}{2}\dim {M}+1\). Here for simplicity we will work in the context of smooth diffeomorphisms since the curvature formulas are the same either way.

References

Arnold, V.I.: On the differential geometry of infinite-dimensional Lie groups and its application to the hydrodynamics of perfect fluids. In: Arnold, V.I. (ed.) Collected works vol. 2. Springer, New York (2014)

Arnold, V.I., Khesin, B.: Topological methods in hydrodynamics. Springer, New York (1998)

Ebin, D.G., Marsden, J.: Diffeomorphism groups and the motion of an incompressible fluid. Ann. Math. 92 (1970)

Ebin, D.G., Misiołek, G., Preston, S.C.: Singularities of the exponential map on the volume-preserving diffeomorphism group. Geom. Funct. Anal. 16, 850–868 (2006)

Ebin, D.G., Preston, S.C.: Riemannian geometry of the quantomorphism group (2013). arXiv:1302.5075

Haller, S., Teichmann, J., Vizman, C.: Totally geodesic subgroups of diffeomorphisms. J. Geom. Phys. 42, 342–354 (2002)

Khesin, B., Lenells, J., Misiołek, G., Preston, S.C.: Curvatures of Sobolev metrics on diffeomorphism groups. Pure Appl. Math. Q. 9, 342–354 (2013)

Luo, G., Hou, T.Y.: Toward the finite-time blowup of the 3D axisymmetric Euler equations: a numerical investigation. Multiscale Model. Simul. 12, 1722–1776 (2014)

Misiołek, G.: Stability of ideal fluids and the geometry of the group of diffeomorphisms. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 42, 215–235 (1993)

Modin, K., Perlmutter, M., Marsland, S., McLachlan, R.: On Euler-Arnold equations and totally geodesic subgroups. J. Geom. Phys. 61, 1446–1461 (2011)

Preston, S.C.: Eulerian and Lagrangian stability of fluid motions, Ph. D. Thesis, SUNY Stony Brook (2002)

Preston, S.C.: Nonpositive curvature on the area-preserving diffeomorphism group. J. Geom. Phys. 53, 226–248 (2005)

Preston, S.C.: On the volumorphism group, the first conjugate point is always the hardest. Commun. Math. Phys. 267, 493–513 (2006)

Rouchon, P.: Jacobi equation, Riemannian curvature and the motion of a perfect incompressible fluid. European J. Mech. B Fluids 11, 317–336 (1992)

Vizman, C.: Curvature and geodesics on diffeomorphism groups. Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Differential Geometry. Braşov, Romania (1999)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The second author gratefully acknowledges support from NSF Grants DMS-1157293 and DMS-1105660.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Washabaugh, P., Preston, S.C. The Geometry of Axisymmetric Ideal Fluid Flows with Swirl. Arnold Math J. 3, 175–185 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40598-016-0058-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40598-016-0058-2