Abstract

The eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) Global score is a self-report measure of global eating disorder (ED) psychopathology. This study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to evaluate the ecological validity of EDE-Q Global scores among obese adults. Fifty obese adults completed the EDE-Q and 2 weeks of EMA ratings prior to initiating eating episodes and subsequently after eating episodes. EMA items assessed behavioral symptoms [i.e., loss of control (LOC) eating and overeating] and cognitive symptoms (i.e., weight/shape concerns, eating concerns, and restraint). EDE-Q Global was associated with increased EMA weight/shape concerns and fear of LOC at pre-eating recordings. EDE-Q Global was associated with increased EMA post-episode weight/shape concerns, eating concerns, LOC eating, and overeating. There was no association between EDE-Q Global and EMA restraint. Results generally supported the ecological validity of EDE-Q Global scores. Future studies of ED psychopathology in obese adults may benefit from considering EDE-Q Restraint separately.

Level of Evidence Level V, descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Individuals with obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30) are particularly at risk for eating disorder (ED) psychopathology, which includes a variety of maladaptive behaviors (e.g., binge eating) and cognitions (e.g., shape and weight overvaluation, restraint) [1]. As a result, a number of studies have focused on the etiology, treatment, and prevention of ED psychopathology among individuals with obesity [2,3,4]. The eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) Global score [5] is a widely used self-report measure of global ED psychopathology, and is used to assess the overall severity of ED symptoms. While substantial research has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity of the EDE-Q and its consistency with the Eating Disorder Examination interview [6], limited research has examined the extent to which the EDE-Q Global score reflects ED symptoms in daily life.

A primary strength of the EDE-Q is the ease of administration as participants can complete the questionnaire on their own, which is cost- and time-effective. In addition, the EDE-Q can be used in online and observational studies. However, self-report questionnaires like the EDE-Q are subject to a number of recall biases. These include recency bias (i.e., recent events are more easily remembered), saliency (i.e., noticeable events are more easily recalled), effort after meaning (i.e., tendency to reconstruct events so that they are consistent with subsequent events), and aggregation of events (i.e., the cognitive processes required to respond based on average or typical experiences are influenced by recency and saliency biases) [7].

Such biases may have the potential to decrease the validity of EDE-Q scores, and the extent to which the EDE-Q Global score is useful in predicting the occurrence of ED psychopathology in individuals’ daily lives is unclear. Given that some research has demonstrated inconsistencies between self-report and EMA measurements [8,9,10], demonstrating the ecological validity of this self-report measure is important to ensure that scores reflect the naturalistic experiences of individuals (especially because the EDE-Q is often used as an outcome measure in treatment and prevention research 11–13]).

Therefore, the present study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data to evaluate the ecological validity of EDE-Q Global scores among a heterogeneous sample of adults with obesity. Specifically, we examined the associations between EDE-Q Global scores and behavioral (i.e., loss of control eating and overeating) as well as cognitive (i.e., weight and shape concerns, eating concerns, and restraint) ED symptoms in the natural environment.

This study sought to answer two important research questions regarding the assessment of global ED psychopathology in adults with obesity. First, to what extent is the EDE-Q Global score a multidimensional measure of cognitive and behavioral eating disorder symptoms that occur in the daily lives of individuals? Second, are other supplementary measures of eating disorder psychopathology necessary to adequately assess eating disorder psychopathology in addition to EDE-Q global? It is important to acknowledge that this dataset has been used in previous papers [14,15,16]. However, the research questions proposed in the current study have not been examined in this dataset, nor in the broader literature, and thus they are important assessment questions in need of study.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were fifty obese (BMI ≥30) adults who were recruited through advertisements and flyers in the USA. The mean BMI of the sample was 40.3 kg/m2 (SD = 8.5; range 30.6–69.7), and the mean age was 43.0 years (SD = 11.9). See Table 1 for demographics and treatment history. Participants were primarily female, Caucasian, and had at least some college education. The majority of participants reported previously being on a supervised diet at some point in their lifetime; obesity medication and psychotherapy for eating and weight problems were less common. Interested participants were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria via phone, and eligible participants scheduled a meeting to receive information about the study. Inclusion criteria were BMI ≥30 and age ≥18, and exclusion criteria were previous gastrointestinal surgery, current pregnancy or breastfeeding, concurrent treatment of obesity, inability to read and understand English, and current or past diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN). Based on structured clinical interviews, 12 participants reported a lifetime diagnosis of DSM-IV binge eating disorder (BED; 5 subthreshold and 7 full threshold). Of these 12 participants, nine participants had a current diagnosis of BED (4 subthreshold and 5 full threshold). Although a minority of participants were formally diagnosed with BED, previous research with this sample indicated that binge eating episodes were endorsed by 96% of participants during EMA [14]. Individuals with a lifetime BED diagnosis had a significantly higher BMI and EDE-Q Global score compared to individuals who never had BED (see Table 2).

After providing informed consent, participants completed in-person assessments, had anthropometric measures taken, and received instructions regarding completion of EMA recordings on palmtop computers. The EMA protocol required participants to report event-contingent ratings before and after every eating episode, which we term pre-eating episode recordings and post-eating episode recordings, respectively. In addition to these event-contingent ratings, participants also completed recordings in response to six semi-random signals. Semi-random signals prompted individuals to complete a survey every 2–3 h between 8:00 am and 10:00 pm. During these random signals, participants were able to report eating episodes that were not recorded previously. No other information from random signals was used in the current study.

Eating episodes included any time food was consumed such as meals and snacks. During recordings of eating episodes, participants were asked a variety of questions about mood, eating behaviors, and other contextual factors. Many of the pre- and post-eating EMA items were adapted from existing self-report/interview measures including the EDE-Q. Participants completed two practice EMA days and then returned to the research laboratory to have practice data reviewed. Participants then completed a 2-week EMA protocol, during which one in-person visit was scheduled for each participant. At this visit, data from palmtop computers were uploaded and participants were provided feedback regarding their compliance. Participants received $150 for completing the EMA protocol and were given a $50 bonus for completing at least 90% of assessments within 45 min of the palmtop signal. This study was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board. Data from the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Measures

EDE-Q

The EDE-Q [5] is a self-report measure that assesses global ED psychopathology, which consists of restraint, eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns. The four subscales are combined to create the Global scale (α for current study = .91).

EMA pre-eating episode contextual factors

Before eating episodes, participants provided responses to several items described below, which were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Pre-episode weight and shape concerns included “I am satisfied with my body shape and weight (recoded),” “I need to lose weight,” and “I feel fat”. Pre-episode restraint was assessed with the item, “I will eat less to lose weight or avoid gaining weight.” Pre-episode eating concerns were assessed with two items: “I am afraid I might lose control over my eating” and “I shouldn’t eat this.”

EMA post-eating episode contextual factors

After eating episodes, participants responded to 11 items, which were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Post-episode eating concerns included “I wish I had eaten less,” “I shouldn’t have eaten what I ate,” and “I felt like I blew it once I started eating so I might as well keep eating.” Post-episode weight and shape concerns included “I am satisfied with my body shape and weight (recoded),” “I need to lose weight,” and “I feel fat.” Post-episode restraint was assessed with the item, “I will eat less to lose weight or avoid gaining weight.” Post-episode loss of control eating was assessed with four items, “When you were eating, to what extent did you feel a sense of loss of control?”, “While you were eating to what extent did you feel that you could not stop eating once you started?”, “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel that you could not resist eating?, and “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel driven or compelled to eat?” Post-episode overeating was assessed with one item “To what extent do you feel that you overate?”

Statistical analyses

For EMA constructs with three or more related items, we created subscales to reduce the overall number of items. To accomplish this, we used multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) separately for pre-episode and post-episode. The following indices were used as guidelines in evaluating model fit: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥.95, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥.95, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤.06, and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) ≤.08 [17]. Constructs with two or less items remained single items as latent variables require at least three indicators to be identified.

Using t tests, individuals with and without lifetime BED status were compared on pre- and post-eating episode variables. In order to examine associations between EDE-Q Global and EMA ratings, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with a gamma function appropriate for skewed data were calculated. GEEs account for non-independence of observations in the data, accommodate data with missing time points, and are particularly useful with non-normal data [18]. An AR1 serial autocorrelation correction was used to account for dependence within the nested data. EMA items and derived subscales were used as dependent variables, and baseline EDE-Q Global was used as the predictor variable. An additional GEE analysis was run using the EDE-Q Restraint subscale as a predictor variable and EMA restraint items as dependent variables.

Results

CFA results

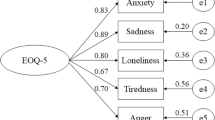

At pre-eating episode, a latent factor was constructed from the EMA items for weight and shape concerns consisting of three items. The model was fully saturated, thus, exhibited perfect fit. All factor loadings were ≥.67 (see Table 3 for factor loadings for individual items). At post-eating episode, latent factors were constructed from the EMA items for weight and shape concerns (3-items), eating concerns (3-items), and loss of control eating (4-items); factors were allowed to freely co-vary. A CFA demonstrated adequate model fit, χ 2 (30) = 127.58, p < .001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .04, and SRMR = .05. All factor loadings were ≥.59 (see Table 3 for factor loadings for individual items). Based on results of the CFAs, EMA items were summed to create composite scales for pre-episode weight and shape concerns, post-episode weight and shape concerns, post-episode eating concerns, and post-episode loss of control eating.

Pre-eating episode associations

Individuals with lifetime BED status reported higher EMA pre-eating weight and shape concerns, fear of loss of control, and feeling that one should not eat compared to individuals never having BED (see Table 2). EDE-Q Global was associated with increased EMA pre-eating episode weight and shape concerns (Estimate = .12, SE = .02, p < .001). EDE-Q Global was also related to EMA fear of loss of control (Estimate = .23, SE = .04, p < .001), but was not associated with EMA feeling that one should not eat (Estimate = .05, SE = .03, p = .11). There was no association between EDE-Q Global and EMA restraint (Estimate = .04, SE = .05, p = .38).

Post-eating episode associations

Individuals with lifetime BED status reported higher EMA post-eating weight and shape concerns, loss of control, overeating, and eating concerns compared to individuals never having BED (see Table 2). EDE-Q Global was associated with increased EMA post-eating episode weight and shape concerns (Estimate = .11, SE = .02, p < .001) and EMA eating concerns (Estimate = .10, SE = .03, p = .002). However, there was no association between EDE-Q Global and EMA restraint (Estimate = .05, SE = .05, p = .30). EDE-Q global was related to both behavioral variables: EMA loss of control eating (Estimate = .20, SE = .05, p < .001) and EMA overeating (Estimate = .18, SE = .04, p < .001).

Additional analyses

Because there was no association between EDE-Q Global and EMA restraint, follow-up analyses were run examining the association between the EDE-Q Restraint subscale and EMA restraint. The Restraint subscale was related to higher pre-episode restraint (Estimate = .11, SE = .04, p = .01) and post-episode restraint (Estimate = .08, SE = .04, p = .04).

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between the EDE-Q Global score and naturalistic symptomatology over a 2-week period among adults with obesity, with a minority also reporting a current or previous diagnosis of BED. Individuals with a current or previous diagnosis of BED had higher EDE-Q Global scores as well as higher scores on most EMA symptom variables, although BED status was unrelated to EMA restraint. Results generally supported the ecological validity of the EDE-Q Global, as evidenced by associations between EDE-Q Global scores and behavioral and cognitive symptoms measured in the natural environment. Specifically, higher EDE-Q Global scores were related to increased pre- and post-eating episode weight and shape concerns, pre-episode fear of loss of control, post-episode eating concerns, loss of control eating, and overeating. Findings are consistent with previous studies [6], and add to existing literature regarding construct and predictive validity of the EDE-Q Global. Its convergence with momentary assessments suggests that this measure appears to be a valid indicator of symptomatology related to weight and shape concerns, eating concerns, and binge eating among adults with obesity.

However, it is worth noting discrepant findings regarding EDE-Q Global scores and restraint measured via EMA. While EDE-Q Restraint was associated with pre- and post-episode restraint, these relationships were not observed with the EDE-Q Global score. Thus, information about restraint in daily life may be lost by combining subscales into a global score; therefore, examining both the Restraint and Global EDE-Q scales may maximize the clinical and research utility of this measure. This consideration is consistent with previous findings suggesting that EDE-Q Global represents two shape/weight-related factors and restraint [19].

The present study is not without limitations. An important factor to consider when designing and implementing EMA studies is participant burden. Because participants are completing multiple assessments over the course of the day, measures used must be brief, often only including one or two items to assess each construct. In addition, it is common in EMA studies to adapt these items from established self-report measures or to create items. Thus, momentary items typically have less specific support for validity, which is certainly a limitation in EMA research. As such, while our validator items assessed numerous aspects of global ED psychopathology, we were not able to measure every aspect of ED psychopathology. For example, restraint in the EMA protocol was assessed by a single item, and may not be a comprehensive representation of features associated with restraint. In addition, the sample was limited to obese adults with and without BED, which precludes generalizability to samples of other age or weight ranges, or ED samples. Finally, we did not include assessments of food craving or other co-occurring psychopathology, and we did not have data on current treatment; these domains may have influenced the observed symptoms in the present study and would be useful to examine in future research. Nevertheless, findings provide preliminary support for both EDE-Q Global and Restraint scales as indicators of behavioral and cognitive manifestations of these constructs in daily life.

References

Hilbert A, De Zwaan M, Braehler E (2012) How frequent are eating disturbances in the population? Norms of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire. PLoS ONE 7:e29125. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029125

Darby A, Hay P, Mond J, Rodgers B, Owen C (2007) Disordered eating behaviours and cognitions in young women with obesity: relationship with psychological status. Int J Obes 31:876–882. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803501

Doyle AC, Goldschmidt A, Huang C, Winzelberg AJ, Taylor CB, Wilfley DE (2008) Reduction of overweight and eating disorder symptoms via the Internet in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health 43:172–179. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.011

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT (2005) Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry 57:301–309. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16:363–370. doi:10.1002/1098108X(199412)16:4%3c363:AID-EAT2260160405%3e3.0.CO;2-#

Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ (2012) Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination-questionnaire: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 45:428–438. doi:10.1002/eat.20931

Yoshiuchi K, Yamamoto Y, Akabayashi A (2008) Application of ecological momentary assessment in stress-related diseases. Biopsychosoc Med 2:13. doi:10.1186/1751-0759-2-13

Solhan MB, Trull TJ, Jahng S, Wood PK (2009) Clinical assessment of affective instability: comparing EMA indices, questionnaire reports, and retrospective recall. Psychol Assess 21:425–436. doi:10.1037/a0016869

Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Shiffman SS (2005) Variability of momentary pain predicts recall of weekly pain: a consequence of the peak (or salience) memory heuristic. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 31:1340–1346. doi:10.1177/0146167205275615

Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Neale JM, Shiffman S, Marco CA, Hickcox M, Paty J, Porter LS, Cruise LJ (1998) A comparison of coping assessed by ecological momentary assessment and retrospective recall. J Personal Soc Psychol 74:1670–1680. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1670

Jacobi C, Völker U, Trockel MT, Taylor CB (2012) Effects of an Internet-based intervention for subthreshold eating disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 50:93–99. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.013

Marzola E, Knatz S, Murray SB, Rockwell R, Boutelle K, Eisler I, Kaye WH (2015) Short-term intensive family therapy for adolescent eating disorders: 30-month outcome. Eur Eat Disord Rev 23:210–218. doi:10.1002/erv.2353

Zabinski MF, Pung MA, Wilfley DE, Eppstein DL, Winzelberg AJ, Celio A, Taylor CB (2001) Reducing risk factors for eating disorders: targeting at-risk women with a computerized psychoeducational program. Int J Eat Disord 29:401–408. doi:10.1002/eat.1036

Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB (2015) Negative affect prior to and following overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. Int J Eat Disord 48:641–653. doi:10.1002/eat.22401

Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Engel SG, Durkin N, Beach HM et al (2014) Ecological momentary assessment of eating episodes in obese adults. Psychosomat Med 76:747–752. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000108

Wonderlich JA, Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Engel SG et al (2015) Examining convergence of retrospective and ecological momentary assessment measures of negative affect and eating disorder behaviors. Int J Eat Disord 48:305–311. doi:10.1002/eat.22352

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6:1–55

Schwartz JE, Stone AA (1998) Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychol 17:6–16. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Grilo CM, Reas DL, Hopwood CJ, Crosby RD (2015) Factor structure and construct validity of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire in college students: further support for a modified brief version. Int J Eat Disord 48:284–289. doi:10.1002/eat.22358

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants P30DK50456 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and T32MH082761 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mason, T.B., Smith, K.E., Crosby, R.D. et al. Does the eating disorder examination questionnaire global subscale adequately predict eating disorder psychopathology in the daily life of obese adults?. Eat Weight Disord 23, 521–526 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0410-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0410-0