Abstract

The application of menthol has recently been researched as a performance-enhancing aid for various aspects of athletic performance including endurance, speed, strength and joint range of motion. A range of application methods has been used including a mouth rinse, ingestion of a beverage containing menthol or external application to the skin or clothing via a gel or spray. The majority of research has focussed on the use of menthol to impart a cooling sensation on athletes performing endurance exercise in the heat. In this situation, menthol appears to have the greatest beneficial effect on performance when applied internally. In contrast, the majority of investigations into the external application of menthol demonstrated no performance benefit. While studies are limited in number, menthol has not yet proven to be beneficial for speed or strength, and only effective at increasing joint range of motion following exercise that induced delayed-onset muscle soreness. Internal application of menthol may provoke such performance-enhancing effects via mechanisms related to its thermal, ventilatory, analgesic and arousing properties. Future research should focus on well-trained subjects and investigate the addition of menthol to nutritional sports products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Menthol applied internally via a mouth rinse or a beverage containing menthol during endurance exercise in the heat is beneficial for performance. |

Menthol is unlikely to have a beneficial effect on endurance exercise performance when applied externally to the skin via a gel or spray. |

Menthol has not yet proven to be beneficial for speed or strength, and only effective at increasing joint range of motion following exercise that induced delayed-onset muscle soreness. |

1 Introduction

The role of the brain in the regulation of exercise performance has received increasing attention over the last decade [1]. Opinion remains divided as to whether regulation occurs exclusively at the neurological level [2] or if interactions between various physiological and psychological feed-forward and feedback mechanisms occur to generate an athlete’s feelings of self [3] and as such, fatigue whilst exercising [4]. What has been repeatedly demonstrated, however, is that physical performance can be modified through interventions acting exclusively on the central nervous system, for example, music [5], experimenter sex [6], and time or performance deception [7]. Various mouth rinsing techniques may also be performance enhancing, which involve briefly exposing the oral cavity to a stimulus (e.g. carbohydrate, caffeine, menthol) with the intention to induce afferent feedback to the brainstem that may ameliorate fatigue [8].

Carbohydrate mouth rinsing has been the main strategy studied to date, with it being postulated that the brief exposure of carbohydrate to the oral cavity elicits neurological responses associated with imminent nutrient availability [9], reward [10] and motor output [10]. These findings led to the emergence of other mouth rinsing strategies [8] including menthol [11]. A menthol mouth rinse is used to impart sensations of coolness, freshness and nasal patency through stimulation of the trigeminal nerve [12, 13] and as an agonist to the TRPM8 channel, which serves as a cold temperature sensor [14]. These mechanisms and resultant sensations explain the prolific use of menthol as a flavouring and fragrance agent in confectionery and medications [15].

Considering hotter perceptions of thermal sensation and discomfort negatively affect endurance exercise performance [16] and menthol has a perceptual cooling effect [12], it may be useful as an ergogenic aid for athletic performance, especially in hot environmental conditions [17]. Additionally, menthol has been proposed as a cooling and analgesic compound useful for application on injured and/or sore muscles, to promote recovery and enhance subsequent contraction force [18]. However, with a vast range of application methods, dosages, exercise protocols and performance outcomes, the beneficial effect of menthol on athletic performance seems equivocal. Hence, the current review aims to provide recommendations for athletes using menthol to enhance athletic performance. The psychophysiological mechanisms of action are also explored and directions provided for future research.

2 Literature Search Methods

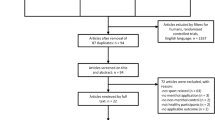

Searching was carried out within the databases PubMed and Scopus up to October 2016. Search terms included menthol, l-menthol, mint, peppermint, counterirritant, cooling, exercise, performance and thermal sensation. Inclusion criteria stipulated that investigations must be written in English and have implemented a menthol-based intervention on a measured aspect of athletic performance. Subjects of all abilities were included and while the majority of studies were performed in a hot environment (>30 °C), investigations performed in neutral-warm environments (20–30 °C) were also included.

3 Menthol and Athletic Performance

To date, the use of menthol as an ergogenic aid for athletic performance has taken the form of a mouth rinse [19], an additive to other beverages [20, 21], or as a gel or spray applied externally to the skin or clothing [22, 23]. Hence, it is either applied internally or externally. Importantly, the degree of the cooling sensation from menthol to a body area correlates inversely with the thickness of the stratum corneum, where a thicker stratum corneum is a more difficult barrier to penetrate [24]. The density of cold-sensitive afferents on a particular body segment will also influence the degree of the cooling sensation from menthol application. Hence, for the same menthol dose, the tongue and oral cavity are more sensitive to menthol in comparison to the torso [24] and as such, the effects of menthol application on the oral cavity (internal) will be discussed separately to application on the skin (external).

3.1 Internal Application of Menthol and Athletic Performance

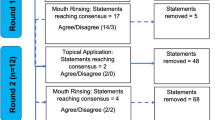

A summary of research determining the effect of internal menthol application on physical capacity and performance appears in Table 1. A novel strategy is to simply rinse (or swill) the mouth with a liquid menthol solution prior to spitting out the solution. In the first study of its type, a menthol mouth rinse (25 mL at a concentration of 0.01% performed every 10 min) significantly improved cycling time to exhaustion by 9% [11]. The researchers also observed significantly increased expired air volume, highlighting a greater drive to breath and/or lowered airway resistance, as well as a lower rating of perceived exertion.

Similar findings have also been observed within running time trials in the heat, where menthol mouth rinse (25 mL at a concentration of 0.01% performed every 1 km) significantly improved 5-km performance time by 3% [19] and 3-km performance time by 3.5% when combined with a facial water spray [25]. Across these studies, significantly increased expired air volume was also observed alongside significantly cooler thermal sensation [19, 25]. Notably, the use of a menthol mouth rinse performed during exercise, whether combined with a facial water spray or not, was significantly more beneficial for running time trial performance in the heat compared with the use of well-established pre-cooling strategies [19, 25]. As such, a menthol mouth rinse performed intermittently during exercise appears to be an effective intervention to improve endurance exercise performance in the heat.

Two promising investigations on internal menthol application and endurance performance have involved ingesting a menthol-aromatised beverage [20, 21]. Riera et al. [20] performed several comparisons of different menthol-aromatised beverages that were ingested prior to and every 5 km during a 20-km cycling time trial in the heat. Menthol-aromatised beverages at 23, 3 °C and ice slurry at −1 °C were compared with a beverage of the same volume and temperature without menthol [20]. The addition of menthol to the 3 °C beverage significantly improved performance time by 9%, while no significant differences were observed in the other conditions. Importantly, however, menthol-aromatised ice slurry was the most beneficial intervention compared with a 23 °C control beverage without menthol. Similar studies out of the same laboratory have also demonstrated that the combination of menthol and ice slurry significantly improved performance in a simulated duathlon in hot conditions compared with other beverages also containing menthol at 28 and 3 °C, by 6 and 3%, respectively [21].

Hence, the addition of menthol to a beverage ingested immediately prior to and during endurance exercise has a performance-enhancing effect, and like the menthol mouth rinse, this strategy is not further enhanced by pre-cooling [26]. For the best outcome, menthol should be added to an ice slurry mixture to maximise cooling. Practically, however, recent research has demonstrated that when given the choice, athletes drink less ice slurry than cold fluid during a cycling time trial, which may contribute to a deteriorated performance and feeling state [27].

Other investigations into menthol ingestion and sports performance have taken the form of peppermint ingestion, which typically contains a high concentration of menthol [28–30]. No performance improvements were gained in an outdoor 400-m running time trial following the ingestion of 5 mL/kg of peppermint extract (50 g of dried mint infused into 1 L of water for 15 min) [28]. Hence, this initial study suggests menthol may not be an effective aid for such short duration activity, but more research is needed to confirm this notion. Other studies to investigate the use of peppermint ingestion as a pre-exercise ergogenic aid [29] or an oral supplement consumed every day for 10 days [30] were tarnished by failing to implement a cross-over design or failing to include a control trial, respectively.

3.2 External Application of Menthol and Athletic Performance

A summary of research determining the effect of external menthol application on physical capacity and performance appears in Table 2. Half of these investigations have involved the spraying of a menthol solution onto the exercise clothing either prior to [31, 32] or during an endurance exercise time trial [22]. Spraying a menthol solution on the exercise clothing at a concentration of 0.05% resulted in no improvements in 40-km cycling time trial performance [31] or 5-km running time trial performance [32] despite significantly cooler thermal sensation and improved thermal comfort in both instances. The spray was also ineffective when the menthol solution was more concentrated (0.2%) and implemented at the 10-km mark of a 16.1-km cycling time trial, despite lower ratings of perceived exertion, cooler thermal sensation and improved thermal comfort [22]. Only one study has demonstrated a beneficial performance effect of an external menthol application when a menthol gel at 8% concentration was applied to the face in a volume of 0.5 g/100 cm2 [16]. This intervention increased total work completed by 21% in a cycling time to exhaustion protocol at a fixed rating of perceived exertion and was also accompanied by significantly cooler thermal sensation and improved comfort. As such, the external application of menthol may need to be applied directly to the face, or at least directly to the skin at a high concentration to have an ergogenic effect. It should be noted, however, that the perceptually driven protocol may be more likely to be affected by an intervention designed to influence perception and hence, further investigation into the application of menthol on the face is needed.

Other investigations that have applied a menthol gel directly to the skin have assessed the effects on muscle strength [18, 33] and joint range of motion [34, 35]. A menthol gel applied to the forearm at a concentration of 3.5% and a volume of 0.5 g/100 cm2 did not improve isokinetic muscle strength 20 min after application [33]. Similarly, a menthol gel with the same concentration and volume applied to the biceps brachii did not improve maximal voluntary contraction or evoked force of the elbow flexors 20 min after application and 48 h after exercise that induced delayed-onset muscle soreness [18]. In regard to joint range of motion, one investigation demonstrated that application of a 2% menthol gel increased range of motion of the elbow joint following an eccentric exercise protocol to induce delayed-onset muscle soreness [35]; however, application of a 16% menthol gel did not affect hamstring range of motion in the absence of preceding eccentric exercise [34]. Therefore, the use of a topical menthol gel appears to have little influence on muscle strength and joint range of motion in the recovered state.

4 Mechanisms of Action

The application of menthol for the improvement of endurance performance in the heat has been proposed to induce several psychophysiological adjustments including thermal [36], ventilatory [19], analgesic [18] and arousal effects [37].

4.1 Thermal Effect

Improved feelings of thermal comfort and sensation are observed when menthol is applied topically [16, 22, 31, 32] and when administered orally [19, 25]. Researchers investigating topical application of menthol often apply garments that have been treated with low-concentration menthol solutions. This facilitates evaporative cooling and stimulation of cold receptors by placing the garment and menthol in contact with large cold-sensitive areas such as the chest and back [38]. Specifically, the solvent (typically water and alcohol) evaporates as a result of an increased rate of heat production and skin temperature during exercise, whilst menthol stimulates cold-sensitive TRPM8 receptors, creating a subjective feeling of coolness [12]. Menthol has, however, also been shown to promote a heat storage response during exercise [36, 39] and at rest [40] as a result of perturbed sweat rate [23] and vasoconstriction of blood vessels [40, 41]. These thermoregulatory responses may explain why topical application of menthol is not beneficial for endurance performance in the heat when applied to large areas, prior to or during an intense and prolonged bout of exercise [40]. When menthol is applied to smaller areas, such as the face, these physiological responses are not observed, yet a cooler thermal sensation and improved thermal comfort still occur [16].

The disassociation between the physiological and perceptual responses to body heat from topical menthol application presents an ethical consideration for researchers, as it may permit exercise beyond normal thermal limits and an increase in the stress hormone prolactin [19]. Application of menthol close to the onset of hyperthermia should be avoided to allow perception of symptoms associated with high levels of heat stress, adjustment to self-selected exercise intensity and the prevention of heat injury.

When administered orally, menthol evokes pleasant and refreshing sensations of airflow and nasal patency, improving thermal comfort and sensation by acting as an afferent to the palatine and trigeminal nerves [13, 15]. Despite performance improvements with oral menthol supplementation when used in conjunction with other cooling methods, thermal perception was not cooler in protocols performed outside of the laboratory [20, 21]. Such a finding suggests that in the presence of airflow, oral application of menthol improves performance by mechanisms beyond improvements in thermal perception.

4.2 Ventilatory Effect

Menthol consistently increases ventilation in the form of expired air volume [11, 19, 25] when administered as a liquid mouth rinse (0.01%) with concomitant improvements in running performance [19, 25] and cycling time to exhaustion [11]. While at rest, oral application of menthol inhibits the drive to breathe [12] and deceases the discomfort experienced during breathing with a restrictive load [42], serving to reduce ventilation [43]. Therefore, because exercise increases the ventilatory requirements of the body, at times to a near-maximal level [44], oral administration of menthol during exercise can lower perceived cardiopulmonary exertion [11], which may allow an overall greater depth and/or rate of breathing. However, there is no evidence that menthol has the capacity to decrease physical airway resistance [13, 45, 46], suggesting the effect is perceptual only [42, 45].

4.3 Analgesic Effect

Menthol has been used for medicinal purposes since ancient times [14] and more recently, it has been suggested to have an analgesic effect for sports injuries, delayed-onset muscle soreness and arthritis [15, 18] and hence its inclusion in many topical creams to reduce musculoskeletal pain. Aside from its cooling effect through the TRPM8 channel, menthol has been demonstrated to inhibit the TRPA1 channel, a mediator of inflammatory pain [47]. While topical application of menthol (3.5%) decreased perceived pain and improved physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis [48], research to date has not investigated the analgesic effects of menthol during exercise in athletes.

4.4 Arousal Effect

Menthol has also been suggested to have arousing properties similar to the feeling of cold air on the face when drowsy [12]. Chewing menthol gum has been associated with improved mental alertness [37] and breathing a menthol fragrance through a mask increased vigilance in a sustained visual attention task [49]. However, in contrast, chewing on a menthol lozenge failed to enhance mood ratings of alertness, hedonic tone and tension during simulated firefighting in the heat [50]. As such, further research is needed to determine if arousal plays a role in the improvement of endurance exercise performance in the heat from internal menthol application.

5 Practical Recommendations

Endurance athletes competing in the heat are recommended to experiment with internal menthol application methods both pre-and mid-exercise. This may take the form of a mouth rinse or a beverage containing menthol by adding 0.1–0.5 g of crushed menthol crystals dissolved in alcohol, to 1 L of water. Alternatively, a pre-mixed l-menthol/alcohol solution that is available commercially as a food additive can be used in the same quantity. Athletes should experiment with different concentrations of menthol in their beverages to find individual limits that are both tolerable and beneficial to performance. Indeed, all attempts at internal menthol application should be trialled thoroughly within mock competition scenarios at race intensities to ensure no adverse consequences are to occur in a race situation.

6 Directions for Future Research

To improve translation for athletes, future research into menthol and sports performance should recruit well-trained subjects. Only half of the investigations presented in Tables 1 and 2 used trained or well-trained subjects, which is known to improve test reliability [51] and is also important to understand the specific responses within this population. It should be noted that for the studies concerning the internal application of menthol and endurance performance, the researchers formulated their own liquid menthol solution for mouth rinsing or ingestion. Hence, development of an optimal solution for these purposes is needed, and further, experimentation with combinations of menthol, carbohydrates, electrolytes and caffeine would increase practicality for athletes. Synthetic compounds with similar cooling effects should also be considered as they may have improved palatability and may be easier to formulate [24].

Future researchers should ensure that the dose of any external solution is specified (in g/cm2) to simplify comparisons between studies and further, assessment of the dose-response relationship is needed for the various menthol application methods. Finally, current research has focussed on the thermal and ventilatory mechanisms of internal menthol application, while the analgesic and arousing properties of menthol may also contribute to improved endurance exercise performance in the heat. Hence, these measures should be incorporated into future research.

7 Conclusion

The majority of research has focussed on the use of menthol to impart a cooling sensation on athletes performing endurance exercise in the heat. In this situation, menthol appears to have the greatest beneficial effect on performance when applied internally. Conversely, only one study observed an improvement in endurance exercise capacity following the external application of menthol. While studies are limited in number, menthol has not yet proven to be beneficial for speed or strength and only effective at increasing joint range of motion following exercise that induced delayed-onset muscle soreness. Internal application of menthol likely stimulates improvements in endurance performance in the heat through thermal and ventilatory mechanisms; however, the analgesic and arousing properties of menthol may also play a role.

References

Noakes TD. Time to move beyond a brainless exercise physiology: the evidence for complex regulation of human exercise performance. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(1):23–35.

St Clair Gibson A, Noakes TD. Evidence for complex system integration and dynamic neural regulation of skeletal muscle recruitment during exercise in humans. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(6):797–806.

Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13(4):500–5.

Marino FE, Gard M, Drinkwater EJ. The limits to exercise performance and the future of fatigue research. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(1):65–7.

Karageorghis CI, Priest DL. Music in the exercise domain: a review and synthesis (Part I). Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2012;5(1):44–66.

Lamarche L, Gammage KL, Gabriel DA. The effects of experimenter gender on state social physique anxiety and strength in a testing environment. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(2):533–8.

Jones HS, Williams EL, Bridge CA, et al. Physiological and psychological effects of deception on pacing strategy and performance: a review. Sports Med. 2013;43(12):1243–57.

Burke LM, Maughan RJ. The Governor has a sweet tooth: mouth sensing of nutrients to enhance sports performance. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15(1):29–40.

Simon SA, de Araujo IE, Gutierrez R, et al. The neural mechanisms of gustation: a distributed processing code. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(11):890–901.

Chambers ES, Bridge MW, Jones DA. Carbohydrate sensing in the human mouth: effects on exercise performance and brain activity. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 8):1779–94.

Mundel T, Jones DA. The effects of swilling an l(-)-menthol solution during exercise in the heat. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(1):59–65.

Eccles R. Role of cold receptors and menthol in thirst, the drive to breathe and arousal. Appetite. 2000;34(1):29–35.

Naito K, Komori M, Kondo Y, et al. The effect of l-menthol stimulation of the major palatine nerve on subjective and objective nasal patency. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1997;24(2):159–62.

Patel T, Ishiuji Y, Yosipovitch G. Menthol: a refreshing look at this ancient compound. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):873–8.

Eccles R. Menthol and related cooling compounds. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1994;46(8):618–30.

Schlader ZJ, Simmons SE, Stannard SR, et al. The independent roles of temperature and thermal perception in the control of human thermoregulatory behavior. Physiol Behav. 2011;103(2):217–24.

Stevens CJ, Taylor L, Dascombe BJ. Cooling during exercise: an overlooked strategy for enhancing endurance performance in the heat. Sports Med. 2016. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0625-7.

Johar P, Grover V, Topp R, et al. A comparison of topical menthol to ice on pain, evoked tetanic and voluntary force during delayed onset muscle soreness. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7(3):314–22.

Stevens CJ, Thoseby B, Sculley DV, et al. Running performance and thermal sensation in the heat are improved with menthol mouth rinse but not ice slurry ingestion. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(10):1209–16.

Riera F, Trong TT, Sinnapah S, et al. Physical and perceptual cooling with beverages to increase cycle performance in a tropical climate. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103718.

Tran Trong T, Riera F, Rinaldi K, et al. Ingestion of a cold temperature/menthol beverage increases outdoor exercise performance in a hot, humid environment. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123815.

Barwood MJ, Corbett J, Thomas K, et al. Relieving thermal discomfore: effects of sprayed l-menthol on perception, performance, and time trial cycling in the heat. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(Suppl. 1):211–8.

Kounalakis SN, Botonis PG, Koskolou MD, et al. The effect of menthol application to the skin on sweating rate response during exercise in swimmers and controls. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(2):183–9.

Watson HR, Hems R, Roswell DG, et al. New compunds with menthol cooling effects. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1978;29:185–200.

Stevens CJ, Bennett KJ, Sculley D, et al. A comparison of mixed-method cooling interventions on pre-loaded running performance in the heat. J Strength Cond Res. 2016. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001532.

Riera F, Tran Trong T, Rinaldi K, et al. Precooling does not enhance the effect on performance of midcooling with ice-slush/menthol. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(1–7). doi:10.1055/s-0042-107597

Maunder E, Laursen PB, Kilding AE. Effect of ad libitum ice slurry and cold fluid ingestion on cycling time-trial performance in the heat. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016:1–19. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2015-0764.

Sönmez G, Çolak M, Sönmez S, et al. Effects of oral supplementation of mint extract on muscle pain and blood lactate. Biomed Hum Kinetics. 2010;2:66–9.

Meamarbashi A. Instant effects of peppermint essential oil on the physiological parameters and exercise performance. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2014;4(1):72–8.

Meamarbashi A, Rajabi A. The effects of peppermint on exercise performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013;10(1):15.

Barwood MJ, Corbett J, White D, et al. Early change in thermal perception is not a driver of anticipatory exercise pacing in the heat. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(13):936–42.

Barwood MJ, Corbett J, White DK. Spraying with 0.20% l-menthol does not enhance 5 k running performance in the heat in untrained runners. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2014;54(5):595–604.

Topp R, Winchester L, Mink AM, et al. Comparison of the effects of ice and 3.5% menthol gel on blood flow and muscle strength of the lower arm. J Sport Rehabil. 2011;20(3):355–66.

Akehi K, Long BC. Application of menthol counterirritant: effect on hamstring flexibility, sensation of pressure, and skin surface temperature. Athletic Train Sports Health Care. 2013;5(5):234–40.

Haynes SC, Perrin DH. Effect of a counterirritant on pain and restricted range of motion associated with delayed onset muscle soreness. J Sport Rehabil. 1992;1(1):13–8.

Gillis DJ, Barwood MJ, Newton PS, et al. The influence of a menthol and ethanol soaked garment on human temperature regulation and perception during exercise and rest in warm, humid conditions. J Therm Biol. 2016;58:99–105.

Smith AP, Boden C. Effects of chewing menthol gum on the alertness of healthy volunteers and those with an upper respiratory tract illness. Stress Health. 2013;29(2):138–42.

Filingeri D. Neurophysiology of skin thermal sensations. Compr Physiol. 2016;6(3):1429.

Gillis DJ, House JR, Tipton MJ. The influence of menthol on thermoregulation and perception during exercise in warm, humid conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110(3):609–18.

Valente A, Carrillo AE, Tzatzarakis MN, et al. The absorption and metabolism of a single l-menthol oral versus skin administration: effects on thermogenesis and metabolic rate. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;86:262–73.

Gillis DJ, Weston N, House JR, et al. Influence of repeated daily menthol exposure on human temperature regulation and perception. Physiol Behav. 2015;139:511–8.

Nishino T, Tagaito Y, Sakurai Y. Nasal inhalation of l-menthol reduces respiratory discomfort associated with loaded breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(1):309–13.

Fisher JT. TRPM8 and dyspnea: from the frigid and fascinating past to the cool future? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11(3):218–23.

Blackie SP, Fairbarn MS, McElvaney NG, et al. Normal values and ranges for ventilation and breathing pattern at maximal exercise. Chest. 1991;100(1):136–42.

Kenia P, Houghton T, Beardsmore C. Does inhaling menthol affect nasal patency or cough? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43(6):532–7.

Pereira EJ, Sim L, Driver H, et al. The effect of inhaled menthol on upper airway resistance in humans: a randomized controlled crossover study. Can Respir J. 2013;20(1):e1–4.

Macpherson LJ, Hwang SW, Miyamoto T, et al. More than cool: promiscuous relationships of menthol and other sensory compounds. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32(4):335–43.

Topp R, Brosky JA, Jr., Pieschel D. The effect of either topical menthol or a placebo on functioning and knee pain among patients with knee OA. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2013;36(2):92–9.

Warm JS, Dember WN, Parasuraman R. Effects of olfactory stimulation on performance and stress. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1991;42(3):199–210.

Zhang Y, Balilionis G, Casaru C, et al. Effects of caffeine and menthol on cognition and mood during simulated firefighting in the heat. Appl Ergon. 2014;45(3):510–4.

Stevens C, Dascombe B. The reliability and validity of protocols for the assessment of endurance sports performance: an updated review. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2015;19(4):177–85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

Christopher Stevens and Russ Best declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stevens, C.J., Best, R. Menthol: A Fresh Ergogenic Aid for Athletic Performance. Sports Med 47, 1035–1042 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0652-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0652-4