Abstract

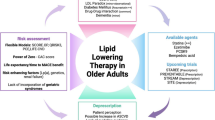

The risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease rises with age and remains the leading cause of death in older adults. Evidence for the use of statins for primary prevention in older adults is limited, despite the possibility that this population may derive significant clinical benefit given its increased cardiovascular risk. Until publication of the 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol, and the 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, guidelines for statin prescription in older adults remained unchanged despite new evidence of possible benefit in older adults. In this review, we present key updates in the 2018 and 2019 guidelines and the evidence informing these updates. We compare the discordant recommendations of the seven major North American and European guidelines on cholesterol management released in the past 5 years and highlight gaps in the literature regarding primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in older adults. As most cardiovascular events in older adults are nonfatal, we ask how clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of continuing a statin for primary prevention in older adults. We also reframe the concept of deprescribing of statins in the older population, using the Geriatrics 5Ms framework: Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multi-complexity, and what Matters Most to older adults. A recent call from the National Institute on Aging for a statin trial focusing on older adults extends from similar concerns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) rises with age and remains the leading cause of death in older adults, accounting for 60% of deaths in those aged 85 years and older [1]. Statins are the cornerstone of pharmaceutical primary prevention of ASCVD and cardiac events. Thus, statin use in those aged 79 years and older has increased fourfold in the past decade [2] in relation to the rise in prevalence of ASCVD in this population [3,4,5,6]. While evidence for the use of statins for primary prevention of ASCVD in those over 75 years of age is limited [6], it is entirely possible that this age group is the most likely to benefit: increased ASCVD risk is almost inevitable with increasing age, including subclinical disease manifestations and accumulating risks of stroke or other severe primary events [7].

Recently, the 2013 American Cardiology Association/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines were replaced by the 2018 American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), American Association Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA), Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC), American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM), American Diabetes Association (ADA), American Geriatrics Society (AGS), American Pharmacists Association (APhA), American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC), National Lipid Association (NLA), and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association (PCNA) Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol (2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines) [8]. The updated 2018 AHA/ACC guidelines include new analyses of prospective and existing cohort data, contributing to relatively novel perspectives regarding potential benefits of statins for primary prevention in older adults [1, 2, 9,10,11,12,13]. Shortly thereafter, the 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease added clarity related to the use of statins for primary prevention in those up to age 75 years (2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines) [14].

In this review, we compare the discordant recommendations of the seven major North American and European guidelines on cholesterol management released in the past 5 years, with respect to primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in older adults, including:

-

US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (VA/DoD, 2014) [15].

-

UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE-UK, 2014) [16].

-

Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS, 2016) [17].

-

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, 2016) [18].

-

European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS, 2016) [19].

-

2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines [8].

-

2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines [14].

While these guidelines were largely derived from the same body of evidence, recommendations for older adults are discordant, highlighting the limitations, variability and ambiguity in the existing data [3, 10, 20]. We present key updates in the 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines [8] and 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines [14] and the evidence informing these updates. We delineate differences among the guidelines in relation to statins for primary prevention in older populations, highlighting current gaps in the literature.

Given that statins are recommended for older adults to prevent debilitating cardiac events, we also explore a novel question: how should clinicians weigh the risks and benefits of continuing a statin for primary prevention in an older adult for whom a statin may have already successfully prevented a cardiac event? We reframe the concept of deprescribing statins in the older population by applying the concepts of ‘time to benefit’ and the ‘Geriatrics 5Ms framework’ (Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multi-complexity, and what Matters Most to older adults) [21]. These approaches help delineate each individual patient’s unique priorities, and facilitate the delivery of individualized care. A recent call for a statin trial focusing on older adults from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) extends from similar concerns.

2 Divergence in Guidelines Remains: Age Cut Points and Defining Cardiovascular (CV) Risk in Older Adults

While all seven major cholesterol guidelines recommend an individualized and shared approach to care, the guidelines differ on several counts. Despite being derived from the same body of evidence, the seven major cholesterol guidelines diverge in two key areas: (1) methods to estimate ASCVD risk; and (2) determination of optimal ages to discontinue statins (Table 1). Within the seven guidelines, four different ASCVD risk estimators have been applied to gauge thresholds of treatment. While these risk estimators all include age in the equation, only the QRISK2 has been validated in those aged 80 years and older (up to age 84 years) [3, 22].

The age cut-offs for statin prescription in older adults without ASCVD varies by guideline, from age 65 years in the ESC/EAS guideline, to no age cut-off in the VA/DoD guideline [15, 19], as shown in Table 1. The VA/DoD guideline advocates for periodic reassessment of ASCVD risk, using a cut-off of 12% 10-year risk of a major adverse cardiac event using the Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) or Framingham Risk Estimator (FRE) [15, 23], rather than an age cut-off. The 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines fall in between, recommending that it is reasonable to consider initiating a moderate intensity statin for those over 75 years of age with a low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) of 70–189 mg/dL, because evidence to date, although of limited quality, points towards benefit in those over 75 years of age [8].

With so much discord between the guidelines on these two critical considerations, we are left to consider the following questions. (1) Should age matter when evaluating clinical risk? (2) What tools are available to define cardiovascular (CV) risk in older adults?

2.1 Should Age Matter?

Age is one of the strongest risk factors for CVD, incorporated into nearly all risk calculators. It is possible that older adults, regardless of age, will derive the greatest net benefit from statin therapy [3, 24,25,26,27]. Assuming that statins for primary prevention in older and younger adults have a similar efficacy, 105,000 myocardial infarction (MI) and 68,000 coronary heart disease (CHD) deaths could be prevented for those aged 75–94 years over 10 years at a cost of $25,000 per disability-adjusted life-year [1, 4].

Existing ASCVD risk calculators are limited in their age range. The PCE is valid up to age 79 years, while data in those beyond age 75 years remain sparse and are an important target for future research [18, 28]. The FRE is not well-validated beyond age 75 years [17], while the ESC/EAS risk estimator (Systemic Coronary Risk Estimation [SCORE]) has not been validated in individuals over age 65 years [19]. The only tool to have included a cohort of adults over 80 years of age (QRISK2) has a maximum age of validity of 84 years. An age of 70 years or older automatically places healthy older adults at moderate risk per QRISK2 [22], rendering it no more helpful than other CVD risk calculators for this age group.

We do not know whether negative functional outcomes, either real or perceived, related to statin use outweigh the benefit of statins in older adults with multimorbidity and an aging physiology as most studies were not powered to detect harm in this complex population [1]. Furthermore the potential benefits of statins in older adults with regard to stroke prevention, the development or progression of peripheral arterial disease, or the effects on cognition and frailty are unclear [3]. To address a patient’s unique risk and benefit profile from a particular statin therapy, consideration should be given in future studies to assessing their effect on the above health outcomes and the qualitative outcomes that are meaningful to older adults [1, 3].

2.2 How Do We Accurately Define CV Risk in Older Adults?

Using most current risk estimators, adults over 75 years of age always reach risk thresholds for statin prescribing; thus, the decision to treat this population with a statin is grounded exclusively in age alone [1, 3, 24, 29]. The lack of a screening tool that discriminates risk beyond age alone highlights an important area for further research to develop a risk calculator that accounts for successful aging. Moreover, none of the existing risk estimators account for important age-related variables such as frailty, cognition, and functional status [10]. This presents a challenge as existing epidemiology suggests that age alone is a significant nonmodifiable risk factor for CVD. New tools that move beyond chronologic age, or the validation of existing tools, in older populations are needed to more accurately estimate ASCVD risk, particularly in those aged 80 years and older [1]. When validating these tools in older populations, consideration of geriatric specific concerns, such as frailty, cognition, function, falls, disability, and functional dependence, may help these estimators better predict clinical risk in older patients with complex medication conditions.

Recommendations in published guidelines do not agree because of the conflicting body of evidence on which they are based. Thus, the NIA has put out a call for a statin trial in older adults. Such a trial will provide critically needed information on the role of statins for primary prevention of ASCVD in older adults, including populations with greater heterogeneity, much older age, and diabetes.

3 Statins for Primary Prevention in Older Adults: Current State of Evidence

The 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines and 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines make several key points about using statins for primary prevention of CVD in older adults. The authors of the 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines note the limitations of ASCVD risk estimators for older adults and recommend stratifying individuals by ASCVD risk score, while also considering risk-enhancing factors and the potential for further lifestyle modifications to determine if the risk estimator is accurate [8]. When considering factors that contribute to CV risk in older adults, beyond age, both the 2018 and 2019 guidelines incorporated data from the BioImage Study, to recommend that coronary artery calcium (CAC) be considered in the risk discussion in addition to clinical risk via the PCE for older adults [8, 14]. The strong negative predictive value of a CAC score of zero suggests statin therapy is not likely to yield clinical benefit for CVD prevention [8].

3.1 Evidence Informing 2018 and 2019 Guideline Updates

The evidence that informed the primary prevention recommendations in the 2018 and 2019 guidelines included retrospective analyses of existing data and new analyses of prospective data, yielding different conclusions, as shown in Table 2 [1, 2, 9,10,11,12,13]. Of note, original data collected in the above studies spanned a wide time period, during which many changes in cholesterol guidelines were made, contributing to possible selection bias within each trial. One positive trial supporting statins for primary prevention in older adults included a meta-analysis that combined randomized controlled trial data from HOPE-3 [30] and JUPITER [31] stratified by age, which showed significant statin benefits regardless of their advanced age [13]; this analysis was limited by the small number of participants over the age of 75 years in the original trials.

In contrast, a post hoc analysis of the nonblinded lipid-lowering component of the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT) stratified a group of older participants with moderate hypertension by age. The results of this analysis showed no significant difference in the risk of all-cause mortality or death from CVD, CHD, or stroke compared with usual care in both the age and treatment groups. This analysis has significant limitations. It was a nonblinded study with high rates of crossover between groups, the sample size in the > 75 years age group was small, and the event rate was low. Furthermore, these findings must be interpreted with caution as the trial was not designed to address the question answered in this post hoc analysis, and the methods were not used to control for confounding by indication [1, 2].

Although there are limitations to nonrandomized trial data, such as confounding by indication, there is also value in using pharmacoepidemiological techniques to understand the role of statins in real-world settings. A retrospective analysis of matched pairs in the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS), originally a randomized trial of aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD, showed significant benefit in all-cause mortality and nonsignificant lower risk of CVD events and stroke, regardless of age or functional status, in statin users [9].

3.2 Analyses Not Included in the 2018 and 2019 Guideline Updates

Newer evidence complicates the picture; the following analyses with conflicting results were not included in the 2018 and 2019 guidelines. A Korean study with similar methods to the PHS analysis matched 639 pairs of statin users and nonusers over 75 years of age. This study supported statin use for primary prevention, with significant reductions in CV events (hazard ratio [HR] 0.59, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.41–0.85, p = 0.005) and all-cause mortality (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.34–0.93, p = 0.024) in statin users [32]. On the other hand, a prospective cohort study using a subcohort of participants over 70 years of age in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) compared statin use at baseline and found no significant difference in event rate in the statin versus no statin group [33]. A retrospective cohort study, published after the most recent guideline was finalized, used data from a cohort of Spanish primary care patients over 75 years of age, stratified by age (75–84 and 85+ years) and presence of diabetes, to examine the role of statins in those without existing ASCVD. No significant reduction in ASCVD or all-cause mortality was found by decade of age in patients without diabetes; however, in those with diabetes, statin use was associated with significant reductions in ASCVD and all-cause mortality, even at an advanced age. This effect diminished in those ≥ 85 years of age and was absent in those ≥ 90 years of age [11]; however, few patients over 85 years of age were included, limiting the power to detect benefit in this age group. A retrospective cohort study conducted in a French population aged 75 years and older examined the association of new statin use with incidence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and all-cause mortality in 3642 matched pairs. The analysis was stratified by statins for secondary prevention, primary prevention with modifiable risk factors, and primary prevention without modifiable risk factors. Statin use was significantly associated with lower risk of ACS or all-cause mortality in the primary prevention with modifiable risk factors group (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.96, p < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the primary prevention without modifiable risk factors group [34].

The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration published a meta-analysis in 2019 analyzing individual participant data of randomized statin trials with a duration at least two years (N = 186,854 participants). The meta-analysis included 28 trials: 5 primary prevention trials, 12 secondary prevention trials, and 11 trials that included participants both with and without existing ASCVD. The 5 primary prevention trials contributed 26% (n = 48,164) of all participants included in the analysis, one-third of whom were enrolled in JUPITER and HOPE-3. Only 11% (n = 19,772) of participants included were 65 years of age and older without a history of ASCVD; < 2% (3306) were over age 75 years. Although an overall significant reduction (21% proportional reduction, relative risk (RR) per 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C 0.79, 95% CI 0.77–0.81) in major vascular events was demonstrated, regardless of age, the generalizability of these conclusions to older adults without ASCVD remains limited by the small number of older participants. In subgroup analysis of older adults without ASCVD, there was a significant trend towards smaller proportional risk reductions with increasing age (RR per 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C 0.75, 95% CI 0.71–0.80, p = 0.05 for trend), although event rates in those over 65 years of age were low in both treatment groups, suggesting a healthy cohort was studied compared with the general population (1.1–2.7% per annum) [35].

Although of variable quality, evidence to date shows some evidence of benefit in some populations aged 75 years and older. While a shared decision-making process is still recommended, older adults may benefit from statin therapy well beyond age 75 years, and it is reasonable to consider continuation of statin therapy for primary prevention in all older adults [8].

4 How Do We Weigh the Possibility of a Successfully Prevented Cardiac Event?

Shared decision making necessitates consideration of multiple issues, including weighing conflicting data in older populations. We add a key question to this process: how can we account for a ‘missed’ cardiac event that has been prevented by a statin taken for primary prevention? Is the possibility that an event was prevented by statin therapy considered when discussing the potential of statin deprescribing?

Consider the illustration in Fig. 1 showing two patients with identical CV risk profiles but different clinical trajectories. Both patients A and B are 65-year-old White men with a 10-year ASCVD risk of 8.5% per PCE. Patient A does not initiate statin therapy, as recommended per the CCS, NICE-UK, and USPSTF, while patient B does initiate statin therapy, as recommended per the ACC/AHA, AHA/ACC, ESC/EAS and VA/DoD. Patient A goes on to experience a cardiac event 3 years later, starts a statin for secondary prevention, and his CV risk continues to increase each year. Patient B, with his statin having reduced his ASCVD risk, does not experience a cardiac event. Patient B’s ASCVD risk continues to increase with age, but not to the degree of patient A, who experienced a cardiac event. Yet at age 75 years, per the ACC/AHA, AHA/ACC, CCS, ESC/EAS, NICE-UK, and USPSTF guidelines, patient B may be considered for statin discontinuation. Due to age alone, patient B likely meets the risk threshold for statin initiation, but evidence of benefit and accurate CV risk estimation for someone his age is unclear.

An illustration of how to weigh a “successfully prevented event”, showing two patients with identical cardiovascular risk profiles and their diverging trajectories based on guideline recommendations for statin therapy [8, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. TC triglycerides, HDL high-density lipoprotein, SBP systolic blood pressure, HTN hypertension, ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, OM diabetes, CV cardiovascular, 1° primary, 2° Secondary, CVD cardiovascular disease, CCS Canadian Cardiovascular Society, NICE-UK The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence United Kingdom, USPSTF United States Preventative Services Task Force, AHA/ACC American Heart Association/American Cardiology Association, ESC/EAS European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society, VA/DoD Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. aIf 10-year risk calculated using the Pooled Cohort Equation. bRoyalty-free image titled “person” by Vaibhav Radhakrishnan from the Noun Project. cRecommend for patient A as per CCS, NICE-UK, and USPSTF. dRecommend for patient Bas per ACC/AHA, AHA/ACC, ESC/EAS and VA/DoD. eRecommend for patient Bas er ACC/AHA, AHA/ACC, CCS, ESC/EAS, NICE-UK, and USPSTF (all guidelines except VA/DoD)

How can we factor in patient B’s successfully prevented event? To date, there is no evidence to directly address this question. The consideration of time to benefit, which accounts for global function and life expectancy, may help clarify this question [36]. While shorter times to benefit have been proposed in younger populations for whom statins are used for secondary prevention [37], the time to benefit for primary prevention in older adults is estimated to be 2–5 years: 2 years for MI prevention and 5 years for stroke prevention [36]. This was derived from randomized controlled trial data in older adults without a history of ASCVD. Furthermore, the majority of ASCVD events in older adults are nonfatal and may be significantly more serious than in younger people, leading to disability or functional decline [3, 38]. As the population lives longer, the extent of older adults living with multimorbidity continues ‘aging into non-evidence-based territory’ [29]; thus, the debate regarding statins for primary prevention in older adults has evolved to consider not just the prevention of CV mortality but also CVD-free and disability-free survival.

Additional analysis of the ALLHAT-LLT data used restricted mean survival time analysis to estimate the total and coronary disease-free survival time projected over the 6-year follow-up period, and up to 10 years, in the statin versus nonstatin groups. Although overall survival time was 33 days shorter for those treated with a statin versus placebo, the statin group gained 19 days free of CHD over 6 years and a projected 78 more days free of CHD over 10 years [39]. The use of disease-free survival time related to primary prevention in older adults represents a paradigm shift toward outcomes that may be more meaningful and reliable compared with previous approaches cited in fluctuating guidelines with ambiguous conclusions.

For an older adult who has successfully aged out of the guidelines and continues to tolerate a statin, it is reasonable to consider continuing the statin. This is supported by a small body of evidence [9, 11, 13, 30] and led to the IIb recommendation in the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline, to recommend statins in those over 75 years of age. Future randomized controlled trials are needed to distinguish which 75-year-olds (and their older counterparts) may benefit from continued statin therapy based on age, risk, and functional (physical and cognitive) status [1]. Until more evidence is available, we recommend using a pragmatic approach in assessing the risks and benefits of statin continuation in adults such as patient B on an individual basis. We reframe the question of deprescribing statins by incorporating the concepts of time to benefit and the Geriatrics 5Ms, as discussed in the next section.

5 Reframing Deprescribing of Statins: Application of the Geriatrics 5Ms

Some clinicians are concerned that older, frail individuals may be at increased risk of statin adverse effects. Deprescribing of statins significantly increases with age and increased frailty level, reaching nearly 18% per year among centenarians in a UK cohort study [38, 40].

Coupled with a limited life expectancy, it remains unclear whether older, frailer individuals with a limited life expectancy will derive benefit from statin therapy for primary prevention [1, 3, 9, 24, 41,42,43]. This may also be true for older adults with life-limiting disease such as end-stage renal disease, end-stage heart failure, advanced dementia, or metastatic cancer [44, 45]. Shared decision making remains a cornerstone of appropriate prescribing for all patients, particularly when considering whether to deprescribe medications where time to benefit may exceed predicted life expectancy. Most importantly, considerations may differ from one older adult to the next. We propose combining the assessment of time to benefit [36] and the Geriatrics 5Ms framework [21] when making a shared decision regarding deprescribing a statin for primary prevention.

As noted above, time to benefit can be used to evaluate the utility of initiation and continuation of preventative interventions [36]. Therefore, for individuals with an estimated life expectancy of < 2 years, it would be reasonable not to initiate or continue a statin for primary prevention, regardless of age. However, the life expectancy for patient B, a 75-year-old male, ranged from 6.0 to 15.6 years. In that case, patient B’s life expectancy likely exceeds the time to benefit for a statin for primary prevention, and the decision to continue or discontinue his statin must incorporate individual patient preference [36]. One may also consider the potential benefits of statin use outside of increasing survival for an individual patient, such as stroke prevention, peripheral arterial disease mitigation, benefits to cognition and the effect of statins on frailty, all which remain unknown [3, 39].

Time to benefit and life expectancy are only two factors to be considered when deciding to initiate or continue a statin for primary prevention for older adults. The Geriatrics 5Ms framework, which was proposed as a tool for communicating the key components of geriatric care, highlight the remainder of these important factors. The Geriatrics 5Ms include mind (cognition, memory, mood), mobility (gait, balance, falls, and function), medications (polypharmacy, adverse effects, deprescribing), multi-complexity (multimorbidity, biopsychosocial context), and matters most (individual goals and preferences) [21]. The 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines include many of these geriatric concepts when considering statins for primary prevention in older adults, citing functional decline (physical or cognitive), multimorbidity, frailty, or reduced life expectancy as causes to re-evaluate statin therapy [8]. These statements are supported by one randomized [44] and two nonrandomized studies [46, 47] evaluating deprescribing statins in older, sicker populations with limited life expectancy. While statin deprescribing may be safe and preferable in some patient populations, these studies reveal the complexity of this decision as many of the frailer individuals with multi-complexity preferred to remain on statin therapy because they were at the highest CV risk [46].

For older adults with frailty, multimorbidity, and a life expectancy of 2 years or more, Fig. 2 suggests how the Geriatrics 5Ms can help clinicians guide the conversation on the risks and benefits of statin therapy [21]. Depending on patient B’s functional status, comorbid conditions, other medications, and preferences, he may or may not benefit from continued statin therapy beyond his current age of 75 years. Incorporating time to benefit and the Geriatrics 5Ms framework can facilitate informed, personalized decision making for older adults like patient B whose complexity and individuality may not be captured in current guidelines.

6 Next Steps and Future Research

A large randomized controlled trial that adequately represents multimorbid, older adults, particularly those aged 80 years and above, and includes women and minorities, is needed. This has been acknowledged as a priority by the NIA [1]. Future trials that assess disability-free or disease-free survival will augment limited primary evidence of statin benefit beyond the prevention of CV death in older adults. Although many unique methods of frailty assessment have been developed for use in clinical trials [48, 49], evidence suggests that many of these tools are equally valid. Despite the heterogeneity of the older adult population, future statin trials should incorporate some method of frailty. Some of the gaps in our current knowledge may be addressed by the upcoming STAREE trial (Statin Therapy for Reducing Events in the Elderly; NCT02099123), a randomized controlled trial in Australians aged 70 years or older without ASCVD, dementia, diabetes, or life-limiting disease, randomized to atorvastatin 40 mg daily or placebo. The investigators excluded individuals with reduced renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 45 ml/min/1.73 m2), chronic liver disease, a Modified Mini-Mental State Examination score < 78, and serious illness likely to cause death within the next 5 years. Primary outcomes of interest included (1) the composite of all-cause mortality, and the development of dementia and disability; and (2) major CV events (MI, ischemic stroke, CV death). Secondary outcomes included the development of diabetes, cancer, cognitive impairment, frailty or disability, transition to residential care facilities, and quality of life [1]. Results are expected some time in the year 2020 [2, 9, 29].

While the results of STAREE will be important, they will not represent a growing proportion of the population, namely multimorbid older adults with severe frailty [1, 3, 9]. Exclusion of individuals with diabetes and kidney disease may lead to lower event rates in this exclusively Australian cohort, and further limit generalizability [1]. Critiques of the STAREE design also note that by enrolling individuals aged 70 years and older, results will likely overlap with the JUPITER and HOPE-3 trials, perpetuating the lack of data in those aged 80 years and older. Furthermore, recent and ongoing trials of novel cholesterol-lowering agents, such as PCSK9 inhibitors, have not included older patients with multimorbidity, and it is unclear what role these drugs should have for primary prevention in older adults. Future research is ongoing in relation to the preferred statin agent and intensity of the statin used in older adults without a history of ASCVD [1]. New directives from the NIA no longer allow for exclusion criteria based on age alone. However, as with many drugs that have not been studied in older adults, it will take years before additional evidence is available to guide treatment plans.

A multidisciplinary team of experts published a joint statement concluding that the evidence for statin use in those aged 75 years and older without ASCVD is insufficient, and outlined key components of clinical trial design for the future investigation of statins for primary prevention in older adults [1]. Specifically, they proposed a pragmatic trial calling for the inclusion of a diverse population of individuals aged 80 years and older with coexistent medical and cognitive frailty, polypharmacy, and multimorbidity, examining outcomes such as function, disability, and harm [RFA-AG-19-020]. Additionally, the panel noted the lack of research on how age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes affect adverse effects of individual statins. Finally, the panel noted the need for better prediction tools estimating ASCVD in multimorbid older patients. Future studies should also consider assessing time to benefit, including the prime age or level of clinical risk to initiate or discontinue statin therapy in older adults [1].

7 Conclusion

As the older population grows in both number and ASCVD risk, clinicians rely on limited data regarding the role of statins for primary prevention of ASCVD in older adults. Further research is needed to understand which older individuals may benefit from preventative statin therapy, using a pragmatic trial design with comprehensive outcome measures to assess the risks and benefits of statin therapy on a complex population of older individuals. While existing cholesterol management guidelines may be helpful, clinicians must use what data and tools are available to make evidence-based decisions for individual patients. We agree with the 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines that while randomized controlled data for patients beyond age 79 years is sparse, considerable randomized and nonrandomized data, as well as data from meta-analyses, support the use of statins for primary prevention in those aged 75 years and older, although questions and ambiguities remain in the literature. We recommend combining the assessment of clinical risk with time to benefit and the Geriatrics 5Ms to prevent undertreatment of older adults with intermediate to high clinical risk, and to limit unnecessary exposure to harm in individuals who may not derive benefit or who prefer to stop statin therapy.

References

Singh S, Zieman S, Go AS, Fortmann SP, Wenger NK, Fleg JL, et al. Statins for primary prevention in older adults-moving toward evidence-based decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(11):2188–96.

Han BH, Sutin D, Williamson JD, Davis BR, Piller LB, Pervin H, et al. Effect of statin treatment vs usual care on primary cardiovascular prevention among older adults: the ALLHAT-LLT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):955–65.

Mortensen MB, Falk E. Primary prevention with statins in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(1):85–94.

Odden MC, Coxson PG, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Goldman L, Bibbins-Domingo K. The impact of the aging population on coronary heart disease in the United States. Am J Med. 2011;124(9):827–833.e5.

Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–19.

Thompson W, Pottegard A, Nielsen JB, Haastrup P, Jarbol DE. How common is statin use in the oldest old? Drugs Aging. 2018;35(8):679–86.

Rich MW, Chyun DA, Skolnick AH, Alexander KP, Forman DE, Kitzman DW, et al. Knowledge gaps in cardiovascular care of the older adult population: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Geriatrics Society. Circulation. 2016;133(21):2103–22.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003 (epub 3 Nov 2018).

Orkaby AR, Gaziano JM, Djousse L, Driver JA. Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2362–8.

Mortensen MB, Nordestgaard B. Comparison of five major guidelines for statin use in primary prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):67–8.

Ramos R, Comas-Cufi M, Marti-Lluch R, Ballo E, Ponjoan A, Alves-Cabratosa L, et al. Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality in old and very old adults with and without type 2 diabetes: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:k3359.

Pagidipati NJ, Navar AM, Mulder H, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED, Pencina MJ. Comparison of recommended eligibility for primary prevention statin therapy based on the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations vs the ACC/AHA Guidelines. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1563–7.

Ridker PM, Lonn E, Paynter NP, Glynn R, Yusuf S. Primary prevention with statin therapy in the elderly: new meta-analyses from the contemporary JUPITER and HOPE-3 randomized trials. Circulation. 2017;135(20):1979–81.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000678 (epub 17 Mar 2019).

United States Department of Veterans Affairs and United States Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction. Guidelines. 2014. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids/VADoDDyslipidemiaCPG.pdf. Accessed 9 Jan 2019.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Clinical Guideline CG181. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre; 2014.

Anderson TJ, Gregoire J, Pearson GJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dawes M, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(11):1263–82.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, Garcia FA, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1997–2007.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts. Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2017;18(7):547–612.

Bennet CS, Dahagam CR, Virani SS, Martin SS, Blumenthal RS, Michos ED, et al. Lipid management guidelines from the departments of veteran affairs and defense: a critique. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):906–12.

Tinetti M, Huang A. The geriatrics 5M’s: a new way of communicating what we do. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):2115.

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, Robson J, Minhas R, Sheikh A, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1475–82.

Downs JR, O’Malley PG. Management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular disease risk reduction: synopsis of the 2014 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):291–7.

Navar AM, Peterson ED. Evolving approaches for statins in primary prevention: progress, but questions remain. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1981–3.

Stone NJ, Intwala S, Katz D. Response by Neil J. Stone, Sunny Intwala, and Dan Katz. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):947–8.

Savarese G, Gotto AM Jr, Paolillo S, D’Amore C, Losco T, Musella F, et al. Benefits of statins in elderly subjects without established cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(22):2090–9.

Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, Daeges M, Jeanne TL. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316(19):2008–24.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889–934.

Gurwitz JH, Go AS, Fortmann SP. Statins for primary prevention in older adults: uncertainty and the need for more evidence. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1971–2.

Yusuf S, Bosch J, Dagenais G, Zhu J, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. Cholesterol lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2021–31.

Glynn RJ, Koenig W, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Ridker PM. Rosuvastatin for primary prevention in older persons with elevated C-reactive protein and low to average low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: exploratory analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):488–96, w174.

Kim K, Lee CJ, Shim CY, et al. Statin and clinical outcomes of primary prevention in individuals aged > 75 years: the SCOPE-75 study. Atherosclerosis. 2019;284:31–6.

Huesch MD. Association of baseline statin use among older adults without clinical cardiovascular disease in the SPRINT TRial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):560–1.

Bezin J, Moore N, Mansiaux Y, Steg PG, Pariente A. Real-life benefits of statins for cardiovascular prevention in elderly subjects: a population-based cohort study. Am J Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.032 (epub 18 Jan 2019).

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):407–15.

Lee SJ, Kim CM. Individualizing prevention for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):229–34.

Barter PJ, Waters DD. Variations in time to benefit among clinical trials of cholesterol-lowering drugs. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(4):857–62.

Ruscica M, Macchi C, Pavanello C, et al. Appropriateness of statin prescription in the elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;50:33–40.

Orkaby AR, Rich MW, Sun R, Lux E, Wei LJ, Kim DH. Pravastatin for primary prevention in older adults: restricted mean survival time analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(10):1987–91.

Gulliford M, Ravindrarajah R, Hamada S, Jackson S, Charlton J. Inception and deprescribing of statins in people aged over 80 years: cohort study. Age Ageing. 2017;46(6):1001–5.

Rich MW. Aggressive lipid management in very elderly adults: less is more. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):945–7.

Stone NJ, Intwala S, Katz D. Statins in very elderly adults (debate). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):943–5.

Holmes HM, Todd A. Evidence-based deprescribing of statins in patients with advanced illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):701–2.

Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr, Ritchie CS, Bull JH, Fairclough DL, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691–700.

Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Peterson D, Reed G, Andrade SE, Mitchell SL. Statin discontinuation in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(11):2095–101.

Garfinkel D, Ilhan B, Bahat G. Routine deprescribing of chronic medications to combat polypharmacy. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015;6(6):212–33.

Qi K, Reeve E, Hilmer SN, Pearson SA, Matthews S, Gnjidic D. Older peoples’ attitudes regarding polypharmacy, statin use and willingness to have statins deprescribed in Australia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):949–57.

Kuchel GA. Frailty and resilience as outcome measures in clinical trials and geriatric care: are we getting any closer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(8):1451–4.

Kim DH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Lipsitz LA, Rockwood K, Pawar A et al. Validation of a claims-based frailty index against physical performance and adverse health outcomes in the health and retirement study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Shoshana Streiter for her assistance with copy editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Dr. Forman is supported by NIA Grants R01-AG060499-01, R01-AG051376, and P30-AG024827. Dr. Orkaby is supported by a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development CDA-2 award (IK2-CX001800), a career development award from the Boston Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, and NIA Grant P30-AG031679, and NIA GEMSSTAR award R03-AG060169. The funders played no role in the publication of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Chelsea E. Hawley, John Roefaro, Daniel E. Forman, and Ariela R. Orkaby have no conflicts of interest to declare that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hawley, C.E., Roefaro, J., Forman, D.E. et al. Statins for Primary Prevention in Those Aged 70 Years and Older: A Critical Review of Recent Cholesterol Guidelines. Drugs Aging 36, 687–699 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00673-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00673-w