Abstract

Background

Psychotropic medicine utilization has increased worldwide among older people (aged 65 years or older), in relation to utilization of other medicines.

Objective

The aim of this population-level study was to describe and characterize the national utilization of psychotropic medicines in older people in New Zealand between 2005 and 2013.

Methods

Repeated cross-sectional analysis of population-level dispensing data was conducted from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2013. Data on utilization of psychotropic medicines were extracted and categorized in accordance with the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system. Utilization was measured in terms of the defined daily dose (DDD) per 1,000 older people per day (TOPD).

Results

Overall, utilization of psychotropic medicines showed a 22.5 % increase between 2005 and 2013. Utilization increased for antidepressants (from 81.9 to 110.4 DDD/TOPD), antipsychotics (from 6.8 to 8.7 DDD/TOPD) and hypnotics and sedatives (from 59.4 to 65.5 DDD/TOPD); in contrast, utilization of anxiolytics decreased (from 11.4 to 10.7 DDD/TOPD). Utilization of atypical antipsychotics increased (from 4.6 to 6.8 DDD/TOPD), with the highest percentage change in DDD/TOPD being contributed by olanzapine (112.1 %), while utilization of typical antipsychotics declined (from 2.0 to 1.5 DDD/TOPD). Utilization of tetracyclic antidepressants and venlafaxine grew rapidly by 1.5 and 4.5 times, respectively, between 2005 and 2013. Utilization of zopiclone was greater than that of other hypnotics in 2013.

Conclusion

Utilization of psychotropic medicines in older people increased by one fifth between 2005 and 2013. Important findings of this study were that: (1) there was a marked increase in utilization of recently funded antidepressants; (2) utilization of atypical antipsychotics increased; (3) there was a move towards utilization of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; (4) utilization of zopiclone remained high; and (5) low, standard and high DDD utilization all increased with time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Overall, utilization of psychotropic medicines in people aged 65 years and older increased by one fifth between 2005 and 2013 |

The annual utilization of zopiclone increased by more than two fifths between 2005 and 2013 (from 33.8 to 48.1 defined daily doses per 1,000 older people per day) with respect to the utilization of hypnotics and sedatives |

Increased utilization of atypical antipsychotics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors appeared to be a compensatory substitution for a decline in utilization of typical antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants, respectively |

1 Introduction

Older people have a high prevalence of mental disorders; hence, studies on utilization of psychotropic medicines in older people (aged 65 years or older) at a population level are gaining importance [1–4]. On the basis of a working definition from the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (WHOCC), psychotropic medicines are classified as psycholeptics (antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and sedatives), which have a central nervous system (CNS)-calming effect, and psychoanaleptics (antidepressants), which have a CNS-arousing effect [5]. In a population-level study conducted in Australia, utilization of antidepressants in older people increased by 41 % between 2002 and 2007 [6]. In Spain, Carrasco-Garrido et al. [7] showed that the number of older people using psychotropic medicines increased by almost 7-fold over a 10-year period. A psychotropic utilization study conducted by Olfson and Marcus [8] in the USA reported that the average number of antidepressants used for older people was increased by 9.8 % in 2005, compared with 1996. Bhattacharjee et al. [9] reported that 63.2 % of the nursing home population in the USA have used at least one class of psychotropic medicine. Similar findings of high psychotropic medicine utilization have been reported in nursing homes in Finland, where four out of five older persons have used psychotropic medicines [10]. In Australia, the rate of utilization of antidepressants in nursing home residents has been reported to be around 33 %, and 23 % were prescribed ≥1 antipsychotic medicine [11, 12].

Population-level studies on utilization of psychotropic medicines specifically in older people in New Zealand have been limited. Several studies in New Zealand have assessed utilization of psychotropic medicines at one time point. Tucker and Hosford [13] found that 54.7 % of older people living in residential care in the Hawke’s Bay region of New Zealand were prescribed one or more psychotropic medicines. In a report by Norris et al. [14] regarding regional variation in antidepressant utilization (measured in capsules per 1,000 people) in New Zealand between 1993 and 1994, Northland had the lowest utilization (134.9 capsules per 1,000 people), whereas the utilization rate in the Canterbury region was 1,415.5 capsules per 1,000 people in the same period. McKean and Vella-Brincat [15] found that the average percentage of the population that was dispensed antipsychotic medication (1.7 %) or antidepressant medication (8.8 %) varied considerably between district health boards in New Zealand for the year 2008–2009. Other studies have looked at changes in psychotropic utilization over time. Roberts and Norris [16, 17] reported increases in antidepressant utilization between 1993 and 1997 in all regions of New Zealand. Exeter et al. [18] showed a 7.4 % increase in antidepressant dispensing between 2004 and 2005 and a 9.4 % increase between 2006 and 2007. In a trend study, McKean and Vella-Brincat [19] identified increased utilization of hypnotics in 2009–2010.

In a 2003 Australian survey of disability, aging and carers, the prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer disease in older people was 17.4 % [20]. A New Zealand survey of 12,929 people in 2003–2004 reported that the mood disorder lifetime prevalence by age for people aged 65 years or older was the same as that of anxiety disorders (10.6 %), and the major depressive disorder prevalence was 9.8 % [1]. The need for pharmacotherapy in older people is evident, but unnecessary or inappropriate use of medicine is associated with potential or actual adverse events, which are dose dependent [21, 22]. Psychotropic medicines have been used to reduce the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia [23] and also to treat bipolar disorder, depression, generalized anxiety, insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, behavioural disorders and other mental illnesses [6, 11]. However, older people are more susceptible to adverse effects of medicines, mainly because of a high burden of illnesses that corresponds with aging [24]. Long-term psychotropic utilization in older people has been associated with increased risks of impaired physical and cognitive function, institutionalization, hospitalization and mortality [25].

There is a paucity of information on overall psychotropic medicine utilization in older age groups in New Zealand at a population level. Psychotropic utilization in older people, stratified in terms of low and high defined daily dose (DDD) values, has not been reported in the New Zealand literature. The objectives of this study, therefore, were (1) to examine the overall utilization of psychotropic medicines in older people living in New Zealand between 2005 and 2013, using data from a national database (Pharms), stratified by sex, age and therapeutic class, based on the WHOCC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification; and (2) to investigate their utilization profile by DDD stratification.

2 Methods

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand (approval number H13/001).

2.1 Study Design

A repeated cross-sectional analysis of population-level dispensing data was conducted from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2013 for individuals aged 65 years or older. Data were extracted on the psychotropic medicines that were used (antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and sedatives), using a unique identifier for each individual case, and analysed for utilization in DDD with regard to sex, age and therapeutic class. The scope of our study included all dispensing claims data made by community pharmacies for all funded psychotropic medicines used in this age group.

2.2 Data Source

De-identified dispensing claims data for individuals aged 65 years or older for the period 2005–2013 were obtained from the New Zealand Ministry of Health (MoH). The Pharms database is a national dispensing claims database maintained by the MoH, which captures subsidized prescriptions dispensed by community pharmacies in New Zealand [26]. The utilization of each psychotropic medicine within an individual was considered in this study. For example, if an individual was dispensed antidepressant and anxiolytic medicines, then that individual would appear in both medicine calculations. Psychotropic medicines were categorized using the ATC developed by the WHOCC [5]. The ATC classification system is subgrouped into five levels, with anatomical, therapeutic, pharmacological, chemical and chemical substance subclasses, in descending order. The ATC therapeutic classes studied at broad levels were antidepressants (N06A), antipsychotics (N05A), anxiolytics (N05B) and hypnotics and sedatives (N05C). The variables used in the present study included each patient’s unique encrypted number, year of dispensing, age at dispensing, sex, dose, daily dose, dosing frequency, strength (weight) of medicine, quantity dispensed and dosage form dispensed.

2.3 Database Analyses

The population dataset included dispensing claims made by community pharmacies for all funded psychotropic medicines for people aged 65 years or older. The figures used to interpret the rates of psychotropic medicine utilization were derived from the same dataset population by sex and age groups from 2005 to 2013. Missing data were negligible (<0.001 % of cases from the population dataset) and were excluded from the analysis. There was no sampling employed in this study, as the dataset was that of the population and was representative of all older people in New Zealand.

2.4 Defined Daily Dose Stratification

The DDD for a medicine is a weighted utilization measure, which corresponds to the mean maintenance daily dose when the medicine is used for its main indication in adults (dosage form not considered) [28]. The mathematical formula is given as:

where ∑ is the summation of all individual dispensings, W is the weight of the medicine, Q is the quantity and ATCDDD is the defined dose for a medicine, fixed by the WHOCC. The standard doses were set by the WHOCC on the basis of the approved dose recommendations for each medicine’s main indication, updated every 3 years and used only for the purpose of examining medicine utilization or for comparing research findings with those from other countries [5]. DDDs were computed for each psychotropic medicine consumed by an individual, yearly, and normalized by sex, age group and therapeutic class at the population level between 2005 and 2013. The DDD per 1,000 older people per day (TOPD), in this context, is a measure of an estimated proportion of people being treated with a daily dose of a medicine, dispensed within a defined study area (dosage form not considered) per 1,000 older people per day [5, 6, 27]. Utilization by sex, age and therapeutic class were also measured in DDD/TOPD values. DDDs were computed for each psychotropic medicine consumed by an individual, yearly, per annual population size of New Zealand between 2005 and 2013.

The ‘DDD stratification’ was derived as a product of the daily dose and weight of each dispensed psychotropic medicine, divided by the standard ATCDDD for the medicine.

The mathematical formula is given in Eq. (2) as:

where Dd is the daily dose for each individual per medicine dispensed and captured as a variable in the Pharms database in individual-level dispensing data. The product of the weight and daily dose of a medicine gives a value that is a proportion of the ATCDDD (the estimated mean daily dose) fixed by the WHOCC. A DDD stratification of a value less than 1 was assigned as ‘low’ (DDD < 1), equal to 1 was assigned as ‘standard’ (DDD = 1) and greater than 1 was assigned as ‘high’ (DDD > 1). For example, citalopram has a weight of 20 mg and a standard ATCDDD of 20 mg (the daily dose is 1) [5]. Therefore, any medicine (citalopram) dispensed to an individual will give a DDD stratification that can be calculated as shown below:

The Dd (daily dose), which is 1 in this case.

3 Results

3.1 Overall Trend

The dataset population extracted from the Pharms database had a 95 % population capture with respect to census population estimates [28] per year. The dataset population (shown in Table 1) was representative of the population; therefore, the data on medicine volumes in DDD/TOPD values were reliable. The national utilization increased by 22.5 % for the year 2013 (195.4 DDD/TOPD) compared with 2005 (159.5 DDD/TOPD).

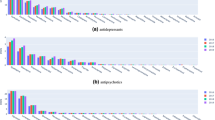

Psychotropic medicine utilization showed an overall increase in DDD/TOPD values from 159.5 in 2005 to 195.4 in 2013 (Table 2). For the therapeutic class, utilization increased yearly in DDD/TOPD values for antipsychotics (from 6.8 to 8.7), hypnotics and sedatives (from 59.4 to 65.5) and antidepressants (from 81.9 to 110.4), while utilization of anxiolytics decreased slightly (from 11.4 to 10.7) between 2005 and 2013 (Table 2; Fig. 1). The percentage utilization changes within each year showed increases in utilization of antidepressants (from 51.3 to 56.5 %) and antipsychotics (from 4.3 to 4.5 %), with decreases in utilization of anxiolytics (from 7.1 to 5.5 %) and hypnotics and sedatives (from 37.2 to 33.5 %) (Table 2).

3.2 Antidepressants

Analysis by therapeutic subclass (Table 2) showed a considerable increase in utilization of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [from 53.9 to 72.4 DDD/TOPD] over the study period. Compared with utilization of SSRIs, utilization of serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs) increased. Utilization of venlafaxine and mirtazapine appeared to be driving these changes (Table 2). Utilization of mirtazapine was not listed for 2005 in Table 2, because it was not yet funded by the government agency that manages prescription medicine funding in New Zealand (the Pharmaceutical Management Agency [PHARMAC]) [29, 30]. Conversely, utilization of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), compared with that of SSRIs, decreased slightly between 2005 and 2013 (from 23.0 to 22.2 DDD/TOPD) when non-funded medicines were considered in the calculations (Table 2). Among the TCAs, utilization of nortriptyline increased considerably, by 64.0 % (Table 2). Analysis by therapeutic subclass within a year showed that utilization of SSRIs had a percentage increase from 33.8 to 37.6 % between 2005 and 2013 (Table 3).

3.3 Antipsychotics

Utilization of atypical antipsychotics (AAPAs) increased between 2005 and 2013 (from 4.6 to 6.8 DDD/TOPD), with the largest percentage changes being contributed by olanzapine (112.1 %) and quetiapine (95.4 %). In contrast, utilization of typical antipsychotics (TAPAs) declined (from 2.0 to 1.5 DDD/TOPD), especially for haloperidol, chlorpromazine, pericyazine, prochlorperazine and trifluoperazine (Table 2). Utilization of AAPAs showed a percentage increase from 2.9 to 3.7 % between 2005 and 2013 (Table 3).

3.4 Benzodiazepines and Hypnotics

Utilization of benzodiazepines (BDZs) remained relatively low (decreasing from 11.2 to 10.5 DDD/TOPD between 2005 and 2013), except for increases in utilization of alprazolam (by 19.0 %) and lorazepam (by 5.7 %). Buspirone, a non-BDZ anxiolytic medicine, had a fairly stable utilization range of 0.1–0.2 DDD/TOPD (Table 2).

The mean utilization of zopiclone was high (40.7 DDD/TOPD) compared with that of other hypnotics (21.3 DDD/TOPD). Among the hypnotics and sedatives, utilization of nitrazepam, lormetazepam and midazolam decreased by more than 30 % each between 2005 and 2013. However, utilization of triazolam and temazepam, which had the highest utilization measures in this therapeutic subclass, decreased by 26 and 36 %, respectively (Table 2). The BDZ percentage utilization declined (from 7.0 to 5.4 %), while the zopiclone percentage utilization was increased in 2013 (from 21.2 to 24.6 %) compared with 2005 (Table 3).

3.5 Defined Daily Dose Stratification

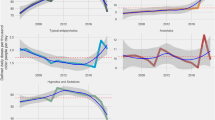

Psychotropic medicine utilization stratified by DDD for the low, standard and high categories (Fig. 2) showed increases from 2005 to 2013. The mean DDD utilization for the low, standard and high strata (33.3, 59.4 and 45.5 DDD/TOPD, respectively) were approximately in a 3:5:4 utilization ratio from 2005 to 2013. Utilization increased in all three categories, with utilization rates of 0.3, 1.4 and 1.4 DDD per year for the low, standard and high strata, respectively.

3.6 Utilization by Sex, Age and Therapeutic Class

Utilization in DDD of psychotropic medicines by sex, age group (5-year bands) and therapeutic class increased and peaked in the 85+-year age group between 2005 and 2013 (Fig. 3). Utilization patterns were similar in trend but lower in magnitude for all age groups in 2005 compared with 2013. Utilization rates of antidepressants, sedatives and hypnotics in females were about 1.5 times those in males. However, anxiolytic and antipsychotic utilization remained relatively unchanged. As seen in Fig. 3, utilization by sex, age and therapeutic class increased in DDD/TOPD values for antidepressants (in females, from 78.0 in the 65- to 69-year age group to 103.9 in the 85+-year age group in 2005, versus from 128.4 to 140.9, respectively, in 2013), hypnotics and sedatives (from 37.5 to 116.0, respectively, in 2005, versus from 52.3 to 131.4, respectively, in 2013). In contrast, utilization increased only marginally for antipsychotics (from 5.9 to 10.4, respectively, in 2005, versus from 9.9 to 10.8, respectively, in 2013) and anxiolytics (from 8.5 to 17.7, respectively, in 2005, versus from 9.5 to 19.6, respectively, in 2013).

4 Discussion

4.1 Overall Trend

Utilization of psychotropic medicines in DDD increased by one fifth (22.5 %) for people aged ≥65 years in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013, with varying contributions to the utilization trend being drawn from the various therapeutic classes. Utilization of antidepressants in this study increased by 34.9 % between 2005 and 2013 (Table 2). In contrast, a population-level study in Australia [31] found that the overall utilization of antidepressants in DDD/TOPD values decreased by 3.7 % between 2004 and 2006. That study also found that BDZ utilization was high in the 85+-year age group, and this was consistent with our findings of increased BDZ utilization in the 85+-year age group compared with the 65- to 69-year age group.

Measurement of psychotropic medicine utilization using the DDD metric allows for comparison of medicine utilization between or within specific or whole population targets in health institutions, states, regions or countries [32]. Examination of utilization trends may not only detect signals of medicine overuse or underuse and their determinants, but may also inform research and clinical practice, leading to changes in prescribing, review of off-label uses, funding restrictions and study of the impact of best-practice prescribing policies.

4.2 Antidepressants

The considerable increase in SSRI utilization in the present study was consistent with findings from other similar utilization studies in older persons [6, 31]. Although antidepressants may be underutilized in the treatment of depression in older people, the increase in utilization may be partly due to the use of SSRIs for generalized anxiety disorder, panic, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder [6, 33–35]. SSRIs are also indicated for prevention of episodes of relapsed depression; they have a lesser tendency to cause toxicity on overdose and a better adverse effect profile than TCAs, which may have contributed to their increased utilization [36, 37]. Citalopram minimally affects the metabolism of co-prescribed medicines, and this may have contributed to its increased utilization [38], though there are concerns that its dose-dependent prolongation of QT intervals in older people increases their risk of cardiovascular adverse effects [39]. Utilization of therapeutic subclasses such as TeCAs and SNRIs increased rapidly. Venlafaxine and mirtazapine appeared to be the medicines driving these changes. The recent funding of ‘newer’ antidepressants (such as venlafaxine, mirtazapine, sertraline and escitalopram) by PHARMAC, the New Zealand organization that subsidizes medicines on behalf of the government, may have contributed to these changes [40–42]. Furthermore, the preferred utilization of venlafaxine in the treatment of resistant depression or relapse treatment [37, 43], despite the requirement for prescribers to obtain special authority approval for each patient on this medicine, may have contributed to these changes [41, 44, 45]. The reduced utilization of TCAs may be related to prescribers’ awareness of their potent anticholinergic effects and role as a contributory factor for falls in older people. However, utilization of nortriptyline increased, possibly because of prescribers’ awareness that it has a lower anticholinergic profile and is an effective treatment option for neuropathic pain in older people [46, 47].

4.3 Antipsychotics

AAPAs have been widely substituted for TAPAs (such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine and trifluoperazine). The compensatory decline in utilization of TAPAs appears to be due to AAPAs’ lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (especially tardive dyskinesia) and fewer anticholinergic side effects [11, 12]. The preference for AAPAs has been consistent with other findings in New Zealand [48] and internationally [49].

Utilization of AAPAs, such as olanzapine and quetiapine, is increasing [48, 50, 51]. These AAPAs are often used for ‘off-label’ indications. Off-label indications for utilization of olanzapine cited in the literature include (but are not limited to) Alzheimer’s disease, anorexia, autism, Asperger’s disorder, insomnia, anxiety and agitation [52–56]. In addition, special authority prescribing restrictions for olanzapine, which required the prescriber to show that specific criteria were fulfilled when requesting a government subsidy, was removed in 2011 [52, 53, 57]. From 1 June 2011, two generic versions of olanzapine became available for prescription without special restriction—Olanzine and Dr Reddy’s Olanzapine (in tablet and dissolving dosage forms) [53]. Experts in New Zealand have supported the evidence for increased short-term use of low-dose quetiapine for symptomatic anxiety and insomnia [58]. McKean and Monasterio [54] found that off-label use of quetiapine was common for anxiety, sedation and post-traumatic stress disorder in some parts of New Zealand. Cumulatively, these changes may have contributed to the increased utilization of AAPAs [53, 58–61]. In the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), AAPAs have demonstrated moderate efficacy in reducing psychotic symptoms, agitation and aggression in older people. However, previous studies have found that utilization of AAPAs for BPSD produced a significant risk of death and stroke, though the effect size was small [59, 60, 62]. Among the AAPAs, low-dose risperidone is recommended for short-term management of psychotic symptoms, agitation and aggression in older people with BPSD [61]. AAPAs should therefore not be used as first-line treatment for frail older people without positive BPSD symptoms. Instead, non-pharmacological therapy is advocated [62, 63]. The findings on AAPA utilization in the present study were similar to the average antipsychotic utilization (20 DDD/TOPD) seen in Australia [6].

4.4 Benzodiazepines and Hypnotics

Utilization of BDZs remained unchanged, except for anxiolytics such as alprazolam and lorazepam, for which utilization was increased in comparison with other BDZs within the subclass; this may have been due to their rapid onset of action [64]. The increased utilization of alprazolam is alarming, however, its indication as a first-line treatment for panic disorder has now been reviewed in Australia because of concerns regarding abuse, dependence and tolerance [31, 65]. The Beers criteria [66–68] for BDZ utilization in older people recommends use of short– to moderate–half-life BDZs because of increased sensitivity to adverse effects in older people. In the present study, utilization of zopiclone was high (> 50 %) compared with that of other hypnotics and sedatives in this subclass. The Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand [69] recommends short-term use of zopiclone (from only a few days to less than 4 weeks) or short-acting BDZs for severe insomnia as the main treatment options, but only after non-pharmacological interventions have failed. The high utilization of zopiclone appeared to be driven by its perceived lack of potential to cause dependence, prolonged sedation or withdrawal symptoms, compared with BDZs [69]. However, Dündar et al. [70] performed a meta-analysis and found that zopiclone reduced sleep latency and duration by the same statistical measure as temazepam and caused worse rebound insomnia than BDZ hypnotics. Holbrook et al. [71] also found that zopiclone was not superior to BDZ hypnotics in terms of the outcomes of sleep latency or duration. The findings on high utilization of zopiclone in this study may prompt prescribers to reduce its utilization, given that it has been shown to be associated with cognitive impairment, confusion, and falls or fractures in older people [70, 72, 73].

Utilization of BDZ hypnotics, such as nitrazepam, lormetazepam and midazolam, declined by 30 % between 2005 and 2013, and this may possibly have been due to substitution with zopiclone. The reduction in utilization of BDZ hypnotics should be welcomed, considering that these agents’ effect on sleep relates more to prolongation than latency and can be complicated by addiction, which makes discontinuation difficult [71, 74]. The Beers criteria recommends avoiding use of high doses of long-acting BDZs for long periods, because of increased sensitivity to BDZs in older people and an increased risk of falls [31, 66]. Clonazepam showed a 7.7 % increase in utilization from baseline, which may suggest that its use has increased in parasomnia, anxiety or panic attack [75, 76].

4.5 Defined Daily Dose Stratification

Utilization of psychotropic medicines was stratified into low, standard and high DDD. DDD stratification provides an opportunity to hypothesize about low and high DDD as being off-label use. The ability to link these data to other clinical information on safety and effectiveness would be useful for clinical practice.

4.6 Utilization by Sex, Age and Therapeutic Class

Psychotropic medicine utilization by sex, age (5-year bands) and therapeutic class showed a similar increasing trend and considerably higher utilization in 2013 than in 2005. Utilization was about 1.5 times the average in females compared with males and was also higher for antidepressants, hypnotics and sedatives than for antipsychotics and anxiolytics. Similar trends have been found in population-level studies in older people in Australia and Spain, with about twice the utilization of antipsychotics in females compared with males [6, 7]. Although previous studies had shown more frequent utilization in females than in males, there may have been other confounding factors, apart from sex, such as a higher proportion of females, a higher prevalence of mental illnesses and higher hospitalization rates in older people [27]. Utilization of psychotropic medicines increased with age and was highest in the 85+-year age group. The peak utilization in the 85+-year age group was evident for antidepressants, hypnotics and sedatives. Kjosavik et al. [77] measured psychotropic medicine utilization in DDD/TOPD values for 2005 among all age groups in Norway. That study found higher volumes of utilization in females aged 60 years or older than we found in the present study with respect to antipsychotics (160.0 in Norway versus 37.0 in New Zealand) and hypnotics and sedatives (466.8 versus 364.5). A population-level study conducted in Australia found that after adjustment for sex and age, females in the 85+-year age group had an average antidepressant utilization of 142.5 DDD/TOPD, which was consistent with the utilization for this therapeutic class found in our study (140.9 DDD/TOPD) during the same period [6].

4.7 Study Strengths and Limitations

Policy makers have an important role in providing high-quality prescribing information based on clinical evidence. This study has extended the discussion on utilization of psychotropic medicines in this age group. Recent New Zealand Government funding of ‘new’ psychotropic medicines may have markedly driven some of the utilization changes that were seen. It is worth mentioning that polices are in place and work is underway to improve psychotropic prescribing in older people in New Zealand. Both PHARMAC and the New Zealand branch of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrist’s Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age have recommended guidelines to rationalize psychotropic medicines in residential care [78]. These recommendations are consistent with psychotropic guidelines in the UK [79, 80], promoting the use of non-pharmacological alternatives and recommending periodic review of psychotropic medicines [78, 81, 82]. Findings from the Older New Zealanders and Antipsychotic Medications Knowledge (OAK) study have highlighted increasing antipsychotic prescribing practice in two New Zealand district health boards and a disconnect between clinical practice and best-practice guidelines [Croucher M, personal communication, 30 June 2014] [83].

One limitation of the current study was the fact that the WHOCC uses mean maintenance doses of medicines’ main indications to compute the DDD, but in practice, changes in recommended doses would reflect a different use or indication. Therefore, a stratified analysis was performed to provide a wider context application of DDD as a proxy to dispensed prescription doses or indications by considering the daily dose for each medicine at individual-level dispensing in the population to give a better profile of high and low utilization of these medicines. Another limitation was the assumption that older people on psychotropic medicines all adhered to their prescribed regimens. There were new entrants into (or exits from) the population aged 65 years or older during the study, but the variations were not sufficient to substantially affect the national population used for the study. Intra-migratory population within the nation was controlled for by using national population data from the database; regional or district measures were not included, in order to prevent a skewed outlook of findings. Unfortunately, the weight of escitalopram, an enantiomer of citalopram, was not captured in the database for the study period; therefore, we were unable to calculate its DDD value. However, it is pertinent to highlight that the Pharms database maintained by the MoH captures the vast majority of dispensings (near total) in older people, as the co-payment is small (NZ$5), and very few prescription medicines would cost less than NZ$5 [30, 45]. In addition, the MoH also maintains databases on hospital admissions, diagnosis, mortality and consultations with general practitioners, which can be linked to the Pharms database via National Health Index numbers. A future study linking the findings of the present study to the above will present an opportunity to study the impact of psychotropic medicine exposure on important clinical outcomes that are relevant to the health of older people at a population level.

5 Conclusion

This population-level utilization study showed a 22.5 % increase in utilization of psychotropic medicines in older people in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013. Important findings were that: (1) there was a marked increase in utilization of the recently funded antidepressants mirtazapine and venlafaxine; (2) AAPA utilization increased as utilization of TAPAs declined; (3) utilization of TCAs and BDZs remained relatively unchanged; (4) utilization of zopiclone remained high despite the risks associated with use in older people; and (5) low, standard and high DDD utilization all increased with time. These findings are consistent with those of similar international studies in older people.

References

Oakley Browne M, Wells J, Scott K. Te Rau Hinengaro. The New Zealand mental health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2006.

Khandelwal SK. Depressive disorders in old age. J Indian Med Assoc. 2001;99:39, 42–4.

Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, et al. Comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders in later life. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:86–93.

Ilyas S, Moncrieff J. Trends in prescriptions and costs of drugs for mental disorders in England, 1998–2010. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:393–8.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. Available from http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_publications/guidelines/. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Hollingworth SA, Lie DC, Siskind DJ, et al. Psychiatric drug prescribing in elderly Australians: time for action. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2011;45:705–8.

Carrasco-Garrido P, Jiménez-García R, Astasio-Arbiza P, et al. Psychotropics use in the Spanish elderly: predictors and evolution between years 1993 and 2003. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:449–57.

Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:848–56.

Bhattacharjee S, Karkare SU, Kamble P, et al. Datapoints: psychotropic drug utilization among elderly nursing home residents in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:655.

Hosia-Randell H, Pitkälä K. Use of psychotropic drugs in elderly nursing home residents with and without dementia in Helsinki, Finland. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:793–800.

Nishtala PS. Determinants of antidepressant medication prescribing in elderly residents of aged care homes in Australia: a retrospective study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:210–9.

Nishtala PS, McLachlan AJ, Bell JS, et al. Determinants of antipsychotic medication use among older people living in aged care homes in Australia. Int J Geriatr Psych. 2010;25:449–57.

Tucker M, Hosford I. Use of psychotropic medicines in residential care facilities for older people in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2008;121:18–25.

Norris P, Calcott P, Laugesen M. The prescribing of new antidepressants in NZ. NZ Fam Phys. 1998;25:45.

McKean A, Vella-Brincat J. Regional variation in antipsychotic and antidepressant dispensing in New Zealand. Australas Psychiatry. 2010;18:467.

Roberts E, Norris P. Growth and change in the prescribing of anti-depressants in New Zealand: 1993–1997. NZ Med J. 2001;114:25–7.

Roberts E, Norris P. Regional variation in anti-depressant dispensings in New Zealand: 1993–1997. NZ Med J. 2001;114:27–30.

Exeter D, Robinson E, Wheeler A. Antidepressant dispensing trends in New Zealand between 2004 and 2007. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2009;43:1131–40.

McKean A, Vella-Brincat J. Ten-year dispensing trends of hypnotics in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2011;124:1–3.

Lafortune G, Balestat G, Disability Study Expert Group Members. Trends in severe disability among elderly people. Available fromhttp://www.oecd.org/denmark/38343783.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Janicak PG, Marder SR, Pavuluri MN. Principles and practice of psychopharmacotherapy. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

Gnjidic D, Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG, et al. Drug Burden Index and physical function in older Australian men. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:97–105.

Wheeler A, Humberstone V, Robinson G. Trends in antipsychotic prescribing in schizophrenia in Auckland. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14:169–74.

Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16:77–84.

Kamble P, Chen H, Sherer J, et al. Antipsychotic drug use among elderly nursing home residents in the United States. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6:187–97.

Narayan S, Hilmer S, Horsburgh S, et al. Anticholinergic component of the Drug Burden Index and the anticholinergic drug scale as measures of anticholinergic exposure in older people in New Zealand: a population-level study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:927–34.

Hollingworth SA, Siskind DJ. Anxiolytic, hypnotic and sedative medication use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:280–8.

Statistics New Zealand. Census QuickStats about national highlights. Available from http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013. Accessed 30 Mar 2014.

Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). Memorandum of understanding relating to the working relationship between PHARMAC and DHBs. Available from http://www.pharmac.health.nz/about/accountability-documents/relationship-agreements. Accessed 17 Mar 2014.

Braae R, McNee W, Moore D. Managing pharmaceutical expenditure while increasing access: the Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC) experience. PharmacoEconomics. 1999;16:649–60.

Smith AJ, Tett SE. How do different age groups use benzodiazepines and antidepressants? Analysis of an Australian administrative database, 2003–6. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:113–22.

Fürst J, Kocmur M. Use of psychiatric drugs in Slovenia in comparison to Scandinavian countries. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12:399–403.

Divac N, Toševski DL, Babić D, et al. Trends in consumption of psychiatric drugs in Serbia and Montenegro 2000–2004. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:835–8.

Stephenson CP, Karanges E, McGregor IS. Trends in the utilisation of psychotropic medications in Australia from 2000 to 2011. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2012;47:74–87.

Damiani G, Raschetti R, Ricciardi W, et al. Impact of regional copayment policy on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) consumption and expenditure in Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:957–63.

Whyte IM, Dawson AH, Buckley NA. Relative toxicity of venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in overdose compared to tricyclic antidepressants. QJM. 2003;96:369–74.

Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653–61.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Prescribing citalopram safely. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/february/citalopram.aspx. Accessed 30 Jun 2014.

Menkes D. New Zealand’s pharmaceutical reference-pricing strategy may backfire. Lancet. 2000;355:558.

Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). Newly-funded antidepressant to meet unmet need—PHARMAC. Available from http://www.pharmac.govt.nz/2009/11/12/Newlyfundedantidepressanttomeetunmetneed.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). Update: New Zealand pharmaceutical schedule. Effective December 2010. Available from http://www.pharmac.govt.nz/2010/11/18/SU.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). Notification of sertraline and escitalopram funding decisions. Available from http://www.pharmac.govt.nz/2010/07/15/2010-07-15PHARMACnotificationofsertralineandescitalopramtenderdecisions.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Hofmeijer-Sevink MK, Batelaan NM, van Megen HJGM, et al. Clinical relevance of comorbidity in anxiety disorders: a report from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord. 2012;137:106–12.

Babar Z-U-D, Grover P, Stewart J, et al. Evaluating pharmacists’ views, knowledge, and perception regarding generic medicines in New Zealand. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2011;7:294–305.

Gleeson D, Lopert R, Reid P. How the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement could undermine PHARMAC and threaten access to affordable medicines and health equity in New Zealand. Health Policy. 2013;112:227–33.

Gilron I, Watson CPN, Cahill CM, et al. Neuropathic pain: a practical guide for the clinician. CMAJ. 2006;175:265–75.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. TCAs are useful for depression and neuropathic pain. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2006/December/tcas.aspx. Accessed 29 Jun 2014.

Wheeler A. Atypical antipsychotic use for adult outpatients in New Zealand’s Auckland and Northland regions. NZ Med J. 2006;119:U2055.

Rapoport M, Mamdani M, Shulman KI, et al. Antipsychotic use in the elderly: shifting trends and increasing costs. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20:749–53.

Philip NS, Mello K, Carpenter LL, et al. Patterns of quetiapine use in psychiatric inpatients: an examination of off-label use. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20:15–20.

Ravindran AV, Al-Subaie A, Abraham G. Quetiapine: novel uses in the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2010;19:1187–204.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Antipsychotics in dementia: best practice guide. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/a4d/resources/guide/guide.asp. Accessed 29 Jun 2014.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Prescribing atypical antipsychotics in general practice. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2011/november/antipsychotics.aspx. Accessed 30 Jun 2014.

McKean A, Monasterio E. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:383–90.

Monasterio E, McKean A. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotic medications in Canterbury, New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2011;124:24–9.

Jackson SHD, Jansen PAF, Mangoni AA. Off-label prescribing in older patients. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:427–34.

Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995–2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:177–84.

Glue P, Gale C. Off-label use of quetiapine in New Zealand—a cause for concern? NZ Med J. 2011;124:10–3.

Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Normand SL, et al. Antipsychotic drug use and mortality in older adults with dementia. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:775–86.

Maher A, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306:1359–69.

Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD003476.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934–43.

Fossey J, Ballard C, Juszczak E, et al. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;332:756–61.

Chouinard G. Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: potency, withdrawal, and rebound. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:7–12.

Moylan S, Giorlando F, Nordfjærn T, et al. The role of alprazolam for the treatment of panic disorder in Australia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2012;46:212–24.

Fick DM, Semla TP. 2012 American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria: new year, new criteria, new perspective. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:614–5.

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, et al. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716–24.

Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly: an update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1531–6.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Managing insomnia. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2008/June/insomnia.aspx. Accessed 20 Jun 2014.

Dündar Y, Dodd S, Strobl J, et al. Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2004;19:305–22.

Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, et al. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ. 2000;162:225–33.

Campbell A, Robertson M, Gardner M, et al. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:850–3.

Ministry of Health. The health of New Zealand adults 2011/12: key findings of the New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012.

Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331:1169–73.

Wilson SJ, Nutt D, Alford C, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1577–601.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Sleep disturbances: managing parasomnias in general practice. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/november/parasomnias.aspx. Accessed 29 Jun 2014.

Kjosavik SR, Ruths S, Hunskaar S. Psychotropic drug use in the Norwegian general population in 2005: data from the Norwegian Prescription Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:572–8.

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. The use of antipsychotics in residential aged care: clinical recommendations developed by the RANZCP Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age (New Zealand). Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/a4d/resources/docs/RANZCP_Clinical_recommendations.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Banerjee S. The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: time for action. Available from https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/AntipsychoticBannerjeeReport.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Antipsychotic use in elderly people with dementia. Available from http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Generalsafetyinformationandadvice/Product-specificinformationandadvice/Product-specificinformationandadvice-A-F/Antipsychoticdrugs/index.htm. Accessed 9 Aug 2014.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Depression POEMs: patient oriented evidence that matters. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/resources/campaign/depression/bpac_depression_poems_wv.pdf. Accessed 30 Jun 2014.

Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Tricyclic antidepressants: prescribing points. Available from http://www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2006/December/docs/tcas_pages22-23.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun 2014.

Croucher MJ, Gee SB. Older New Zealanders and Antipsychotic Medications Knowledge Project: understanding current prescribing practice. Wellington: PHARMAC; 2011.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Analytical Services, New Zealand Ministry of Health, for supplying the dispensing data extracted from the Pharms database. Henry C. Ndukwe was funded by a doctoral scholarship from the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Disclosure statement The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis or data interpretation.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ndukwe, H.C., Tordoff, J.M., Wang, T. et al. Psychotropic Medicine Utilization in Older People in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013. Drugs Aging 31, 755–768 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0205-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0205-1