Abstract

Background

Psychotropic medicine utilisation in older adults continues to be of interest because of overuse and concerns surrounding its safety and efficacy.

Objective

This study aimed to characterise the utilisation of psychotropic medicines in older people in New Zealand.

Methods

We conducted a repeated cross-sectional analysis of national dispensing data from 1 January, 2005 to 31 December, 2019. We defined utilisation using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification defined daily dose system. Utilisation was measured in terms of the defined daily dose (DDD) per 1000 older people per day (TOPD).

Results

Overall, the utilisation of psychotropic medicines increased marginally by 0.42% between 2005 and 2019. The utilisation increased for antidepressants (72.42 to 75.21 DDD/TOPD) and antipsychotics (6.06–19.04 DDD/TOPD). In contrast, the utilisation of hypnotics and sedatives (53.74–38.90 DDD/TOPD) and anxiolytics decreased (10.20–9.87 DDD/TOPD). The utilisation of atypical antipsychotics increased (4.06–18.72 DDD/TOPD), with the highest percentage change in DDD/TOPD contributed by olanzapine (520.6 %). In comparison, utilisation of typical antipsychotics was relatively stable (2.00–2.06 DDD/TOPD). The utilisation of venlafaxine increased remarkably by 5.7 times between 2005 and 2019. The utilisation of zopiclone was far greater than that of other hypnotics in 2019.

Conclusions

There was only a marginal increase in psychotropic medicines utilisation from 2005 to 2019 in older adults in New Zealand. There was a five-fold increase in the utilisation of antipsychotic medicines. Continued monitoring of psychotropic medicine utilisation will be of interest to understand the utilisation of antidepressants and antipsychotic medicines during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The utilisation of atypical antipsychotic medicines relative to typical antipsychotics increased between 2005 and 2019 despite the risk of adverse metabolic effects posed by atypical antipsychotic medicines. |

Despite a reduction in the utilisation of zopiclone in 2019 (25.67 defined daily dose/1000 older people per day) compared with 2005 (29.90 defined daily dose/1000 older people per day), its utilisation relative to other hypnotics and sedatives is greater in 2019. |

An interrupted time series to understand the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on psychotropic drug consumption will be of future interest. |

1 Introduction

The utilisation of psychotropic medicines in older adults (aged 65 years or older) continues to be of interest because of overuse [1] and concerns surrounding their safety and efficacy [2]. Psychotropic medicines are associated with adverse clinical outcomes in older adults, including impairments in physical and cognitive functioning [3], greater hospitalisations [4] and a higher mortality risk [5]. Broadly, as a class, they can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain [6], oversedation [7], anticholinergic side effects [8, 9], extrapyramidal symptoms [10, 11] and dependence [12, 13].

Several factors drive psychotropic utilisation, including reimbursement policies [14, 15], subsidy arrangements [16], co-payments, clinical guidelines [7] and pharmaceutical policies [17]. For example, in New Zealand (NZ), the Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC) subsidises prescription and therapeutics, and the Royal Australian and NZ College of Psychiatrist’s Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age have recommended guidelines to rationalise psychotropic medicines [18, 19]. Collectively, examining psychotropic utilisation can inform research and clinical practice, help understand prescribing patterns, the rates of off-label use [20] and funding restrictions [21] and to study the impact of regulatory warnings on prescribing [22].

This study sequels our national study on psychotropic medicine utilisation in older people in NZ from 2005 to 2013 [23]. Several small-scale studies have been conducted on psychotropic utilisation in NZ. For example, in the residential care setting, Tucker and Hosford found that 54.7% of older people in the Hawke’s Bay region in NZ were prescribed one or more psychotropic medicines [24]. In addition, Roberts and Norris reported an increase in antidepressant utilisation between 1993 and 1997 in all regions of NZ [25]. Similarly, Ndukwe et al. found a variation in psychotropic prescribing from 7% to 74% across district health boards in NZ from 2000 to 2013 [26]. However, there are limited data on understanding the trends in psychotropic utilisation over a long period. Since the most recent study published in NZ in 2015 [23], antipsychotics (paliperidone) and hypnotics and sedatives (melatonin) have been introduced and psychotropics discontinued (mianserin, fluphenazine decanoate, trifluoperazine, alprazolam and lormetazepam). The aim of this study, therefore, was to provide an updated analysis to describe and characterise the national trend in the utilisation of psychotropic medicines in older people by age, sex, and type based on the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) drug classification system of psychotropic medicines used in New Zealand from 2005 to 2019.

2 Methods

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Bath, UK (form number 7423).

2.1 Study Design

A retrospective national study of medicine utilisation was undertaken for those aged 65 years and above.

2.2 Data Source

We obtained de-identified dispensing claims data for individuals aged 65 years or older for 2005–19 from the NZ Ministry of Health. The dispensing claims data were extracted from the Pharmaceutical collection by the information analyst at Data Services, Ministry of Health [27, 28]. The Pharmaceutical collection contains medicines funded by PHARMAC. PHARMAC is the New Zealand government agency that decides which pharmaceuticals to fund in NZ publicly and provides funded access to pharmaceuticals for all New Zealanders [18].

2.3 Defined Daily Dose per 1000 Older People Per Day

A defined daily dose (DDD) is the average maintenance dose for the medicine for its main indication in adults. The WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology updates DDDs every 3 years. It is a recommended metric for drug utilisation studies as it allows comparisons across countries and regions and evaluates trends over time [29]. The DDD per 1000 older people per day (TOPD) measures the proportion of people treated with a defined daily dose of medicine per 1000 older people per day [7].

2.4 Psychotropic Drug Utilisation

Psychotropic medicines were categorised based on the ATC classification system of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology [28]. For this analysis, we considered antidepressants (NO6A), antipsychotics (NO5A), anxiolytics (N05B) and hypnotics and sedatives (N05C). We completed the analyses at the therapeutic and chemical levels. The total quantity dispensed for each chemical was extracted from Pharms data and converted to DDD equivalents. The DDD/TOPD was derived by summing the total DDD for 1 year, dividing by the census population and multiplying by 1000. For example, the value of 14 DDD for citalopram in 2005 suggests that 14 out of the 1000 older people in NZ were dispensed a standard dose of 20 mg of citalopram per day. Customised census population data were extracted from NZ statistics [30].

3 Results

3.1 Overall Psychotropic Medicine Utilisation

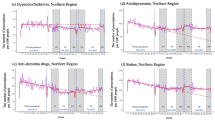

Psychotropic medicine utilisation was relatively unchanged from 2005 to 2019 (142.42–143.02 DDD/TOPD), corresponding to a 0.42% increase in psychotropic utilisation (Table 1). In addition, utilisation increased for antipsychotics (6.06–19.04 DDD/TOPD) and antidepressants (72.42–75.21 DDD/TOPD). In contrast, utilisation decreased for anxiolytics (10.20–9.87 DDD/TOPD) and hypnotics and sedatives (53.74–38.90 DDD/TOPD) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Psychotropic utilisation in NZ in older adults aged 65 years and above, by psychotropic classes, 2005–19. The red dotted line represents the mean defined daily dose per 1000 older people per day and is calculated by dividing the sum of the defined daily doses per 1000 older people per day for all years by the study period (15 years)

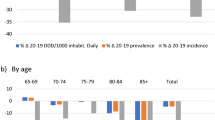

3.2 The Utilisation of Psychotropic Medicines by Age and Sex

The utilisation of psychotropic medicines by age (5-year bands) and sex (DDD/TOPD) and type from 2005 to 2019 increased and peaked in the 95 years and over age group (Fig. 2). The utilisation of antidepressants was highest among all age groups and across both sexes except for the 90–94 years and 95+ years age groups, where hypnotics and sedatives were higher than the utilisation of antidepressants. The utilisation of typical antipsychotics decreased across age groups in both sexes. In contrast, the utilisation of atypical antipsychotics increased remarkably across all age groups and in both sexes.

3.3 Antidepressants

The utilisation of antidepressants increased by 3.08% from 2005 to 2019 (72.42–75.21 DDD/TOPD). Specifically, the utilisation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) declined slightly (47.67–45.36 DDD/TOPD). In contrast, tetracyclic antidepressants and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors increased considerably. Interestingly, the utilisation of tricyclic antidepressants declined substantially (20.37–5.44 DDD/TOPD) (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Typical antipsychotic utilisation in older adults aged 65 years and above by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (NO5A), 2005–19. The blue dotted line represents the mean defined daily dose per 1000 older people per day and is calculated by dividing the sum of the defined daily doses per 1000 older people per day for all years by the study period (15 years)

3.4 Antipsychotics

Atypical antipsychotic medicine utilisation increased (4.06–18.72 DDD/TOPD) markedly, mainly driven by olanzapine (1.31–8.13 DDD/TOPD) and quetiapine (0.78 to 3.99 DDD/TOPD) (Table 1, Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that in 2014, PHARMAC funded paliperidone, and its utilisation in 2019 was 0.18 DDD/TOPD. In contrast, the utilisation of typical antipsychotic agents is relatively low and remains almost unchanged (2.00–2.06 DDD/TOPD) over the study period (Table 1, Fig. 5).

Atypical antipsychotic utilisation in older adults aged 65 years and above by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (NO5A), 2005–19. The blue dotted line represents the mean defined daily dose per 1000 older people per day and is calculated by dividing the sum of the defined daily doses per 1000 older people per day for all years by the study period (15 years)

Antidepressant utilisation in older adults aged 65 years and above by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (N05A), 2005–19. The blue dotted line represents the mean defined daily dose per 1000 older people per day and is calculated by dividing the sum of the defined daily doses per 1000 older people per day for all years by the study period (15 years)

3.5 Anxiolytics

Benzodiazepine (BDZ) utilisation decreased by 3.7% (10.05–9.68 DDD/TOPD) with a rise in the use of lorazepam (5.10–7.00 DDD/TOPD). In addition, for buspirone, a non-BDZ anxiolytic medicine, the utilisation was relatively steady (0.15–0.19 DDD/TOPD) (Table 1, Fig. 6).

3.6 Hypnotics and Sedatives

In 2019, the utilisation of zopiclone was also relatively high (25.67 DDD/TOPD) compared with other hypnotics (13.23 DDD/TOPD). Interestingly, among the BDZ-hypnotic class, the utilisation for nitrazepam, temazepam, and triazolam decreased considerably by 85.9%, 57.0%, and 79.4%, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 7).

4 Discussion

4.1 Psychotropic Utilisation

The utilisation of psychotropic medicines measured in DDD/TOPD was relatively stable in people aged 65 years and older in New Zealand from 2005 to 2019.

4.2 Antidepressants

The slight increase in the utilisation of SSRI antidepressants and a corresponding decrease in utilisation of anxiolytics and tricyclic antidepressants in our study may be driven by multiple factors, including expanding indications for SSRIs beyond the treatment of depression, including obsessive-compulsive disorders [31], panic disorders [32], chronic pain [33] and its preferential use over anxiolytics for anxiety disorders [34]. Citalopram continued to be the favoured SSRI with the highest utilisation both in 2005 and 2019. An expert consensus guideline on the pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders for older adults rated citalopram the highest for efficacy and tolerability among the SSRIs [35]. The utilisation of tricyclic antidepressants decreased substantially. The increased utilisation of serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors and tetracyclic antidepressants is largely driven by venlafaxine and mirtazapine, respectively. Venlafaxine and mirtazapine are recommended second-line treatments for depression after an initial trial of an SSRI, and a systematic review found that they are more effective than paroxetine and fluoxetine [36].

Interestingly, randomised clinical trials that compared venlafaxine to other SSRIs found its safety in older adults is comparable to SSRIs, and the risk for venlafaxine-induced electrocardiogram changes and corrected QT prolongation is low [37, 38]. In clinical practice, the selection of antidepressants in older adults must be guided by patient-specific factors such as comorbidity and susceptibility to anticholinergic effects. Citalopram and sertraline have few drug interactions, are less anticholinergic than tricyclic antidepressants and are recommended for treating depression in older adults.

4.3 Antipsychotics

Despite the increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic adverse effects [39, 40], the utilisation of atypical antipsychotic medicines increased (4.06–18.72 DDD/TOPD) in older people. However, a corresponding decline in typical antipsychotic medicine (2.00–2.60 DDD/TOPD) utilisation occurred, potentially because of the increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms and the perceived benefit of better efficacy for atypical antipsychotics [41]. Nevertheless, the preferential use of atypical antipsychotics over typical antipsychotics is a consistent finding in NZ [42] and internationally despite no evidence for their superiority in terms of efficacy or safety [43, 44]. In 2019, among the typical antipsychotic medicines, haloperidol utilisation was the highest, and among the atypical antipsychotic medicines, olanzapine was the highest. Additionally, in a study comparing 16 countries, quetiapine was the antipsychotic used in most countries, followed by risperidone and olanzapine [45].

Furthermore, the increased use of atypical antipsychotics may be attributed to them often being prescribed for other mental disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, insomnia and agitation [46]. The utilisation of clozapine increased from 0.18 to 0.81 DDD/TOPD. An international study involving 17 countries found that clozapine is still underutilised across several countries despite increased use in recent years. The study found that Finland, followed by New Zealand, has the highest clozapine utilisation rates [47].

In older adults, the risk of anticholinergic effects, extrapyramidal symptoms, the adverse cardiovascular effects of typical antipsychotic medicines and the risk of adverse metabolic effects posed by atypical antipsychotic medicines must be considered. Therefore, the recommendation to treat psychosis in older adults is to use low-dose atypical antipsychotic medicines for the shortest possible duration and wherever feasible on a case-to-case basis to switch to non-pharmacological options [48].

4.4 Anxiolytics

Benzodiazepine utilisation decreased slightly. In 2019, lorazepam was the most widely used benzodiazepine. In our published study in 2015, we highlighted concerns regarding using alprazolam and concerns about abuse, dependence and tolerance [49]. Interestingly, in 2016, PHARMAC stopped funding for alprazolam for new patients [50].

4.5 Hypnotics and Sedatives

Overall, the utilisation of hypnotics and sedatives has declined in NZ older adults (53.74–38.90 DDD/TOPD), but the higher utilisation of zopiclone relative to other BDZs is alarming. Similar concerns of high prescribing of zopiclone in older adults relative to other BDZs were reported in Europe and England [51]. In 2015, we highlighted the risk posed by zopiclone, which accounted for more than 50% of utilisation of hypnotics, as it has been associated with cognitive impairment [52], confusion, and falls or fractures in older people [53], the reduction in the utilisation of zopiclone in 2019 (25.67 DDD/TOPD) compared to 2005 (29.90 DDD/TOPD) is a welcome change.

The high utilisation of zopiclone relative to other hypnotics in 2019 could be attributed to the increased prevalence of insomnia in older adults [54, 55]. However, its use should be restricted to short-term use to mitigate harm in older adults, and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of insomnia must be given precedence [56].

4.6 Strengths and Limitations

One limitation of the study was that the WHO uses doses for the main indications to compute DDDs, but several psychotropic medicines have expanded indications. Therefore, we could not examine the appropriateness of treatment because of a lack of information on the indication for using psychotropic medicine. We also assumed that all adhered to their prescribed psychotropic regime; hence actual utilisation may be overestimated. However, it is pertinent to highlight that the Pharmaceutical collections maintained by the Ministry of Health are comprehensive. In addition, the reimbursement system captures greater than 95% of the prescription coverage of the census population of older adults, strengthening the validity of our study findings.

5 Conclusions

Psychotropic medicine utilisation was relatively stable from 2005 to 2019 in older adults in NZ. Though antidepressant utilisation remained relatively stable, there was a five-fold increase in antipsychotic medicine use mainly driven by the increased utilisation of atypical antipsychotics. Our findings suggest that a high proportion of older adults have been prescribed olanzapine and zopiclone, and the reasons for their use and the risk-benefit ratio warrant further investigation. In addition, the rising trend in the utilisation of melatonin recently funded by PHARMAC should be monitored closely. Continued monitoring of psychotropic medicine utilisation will be of great interest to understand if the utilisation of psychotropic medicines, particularly antidepressants and antipsychotic medicines during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic year, will change relative to previous years and how the changes will impact the health of older adults in the long term.

References

Bednarczyk E, Cook S, Brauer R, Garfield S. Stakeholders’ views on the use of psychotropic medication in older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2022;51(3):afac060. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac060.

Bobo WV, Grossardt BR, Lapid MI, Leung JG, Stoppel C, Takahashi PY, et al. Frequency and predictors of the potential overprescribing of antidepressants in elderly residents of a geographically defined U.S. population. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2019;7(1):e00461. https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.461.

Cullen B, Smith DJ, Deary IJ, Pell JP, Keyes KM, Evans JJ. Understanding cognitive impairment in mood disorders: mediation analyses in the UK Biobank cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(5):683–90. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.188.

Wojt IR, Cairns R, Clough AJ, Tan ECK. The prevalence and characteristics of psychotropic-related hospitalisations in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(6):1206-14.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.035.

Gerhard T, Huybrechts K, Olfson M, Schneeweiss S, Bobo WV, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Comparative mortality risks of antipsychotic medications in community-dwelling older adults. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(1):44–51. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.122499.

Bernardo M, Rico-Villademoros F, García-Rizo C, Rojo R, Gómez-Huelgas R. Real-world data on the adverse metabolic effects of second-generation antipsychotics and their potential determinants in adult patients: a systematic review of population-based studies. Adv Ther. 2021;38(5):2491–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01689-8.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_methodology/purpose_of_the_atc_ddd_system/. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

López-Álvarez J, Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones J, Agüera-Ortiz L. Anticholinergic drugs in geriatric psychopharmacology. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01309.

Gerretsen P, Pollock BG. Drugs with anticholinergic properties: a current perspective on use and safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(5):751–65. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2011.579899.

Dilks S, Xavier RM, Kelly C, Johnson J. Implications of antipsychotic use: antipsychotic-induced movement disorders, with a focus on tardive dyskinesia. Nurs Clin N Am. 2019;54(4):595–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2019.08.004.

Zádori D, Veres G, Szalárdy L, Klivényi P, Vécsei L. Drug-induced movement disorders. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(6):877–90. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2015.1032244.

Baldwin DS, Aitchison K, Bateson A, Curran HV, Davies S, Leonard B, et al. Benzodiazepines: risks and benefits: a reconsideration. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(11):967–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881113503509.

Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, Flament M, Limosin F. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: risk factors, consequences, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0727-9.

Hirano Y, Ii Y. Changes in prescription of psychotropic drugs after introduction of polypharmacy reduction policy in Japan based on a large-scale claims database. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39(11):1077–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-019-00838-w.

Jackson JW, Fulchino L, Rogers J, Mogun H, Polinski J, Henderson DC, et al. Impact of drug-reimbursement policies on prescribing: a case-study of a newly marketed long-acting injectable antipsychotic among relapsed schizophrenia patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(1):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4354.

Kjosavik SR, Gillam MH, Roughead EE. Average duration of treatment with antidepressants among concession card holders in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(12):1180–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415621392.

Leopold C, Zhang F, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Vogler S, Valkova S, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Impact of pharmaceutical policy interventions on utilisation of antipsychotic medicines in Finland and Portugal in times of economic recession: interrupted time series analyses. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-53.

Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). Online pharmaceutical schedule: March 2022. https://schedule.pharmac.govt.nz/ScheduleOnline.php. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. The use of antipsychotics in residential aged care: clinical recommendations developed by the RANZCP Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age (New Zealand). https://www.ranzcp.org/files/resources/college_statements/practice_guidelines/. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

Højlund M, Andersen JH, Andersen K, Correll CU, Hallas J. Use of antipsychotics in Denmark 1997–2018: a nation-wide drug utilisation study with focus on off-label use and associated diagnoses. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30: e28. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796021000159.

Damiani G, Federico B, Silvestrini G, Bianchi CB, Anselmi A, Iodice L, et al. Impact of regional copayment policy on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) consumption and expenditure in Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4):957–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1422-3.

Georgi U, Tesch F, Schmitt J, de With K. Impact of safety warnings for fluoroquinolones on prescribing behaviour: results of a cohort study with outpatient routine data. Infection. 2021;49(3):447–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01549-7.

Ndukwe HC, Tordoff JM, Wang T, Nishtala PS. Psychotropic medicine utilisation in older people in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(10):755–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0205-1.

Tucker M, Hosford I. Use of psychotropic medicines in residential care facilities for older people in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2008;121(1274):18–25.

Roberts E, Norris P. Regional variation in anti-depressant dispensings in New Zealand: 1993–1997. N Z Med J. 2001;114(1125):27–30.

Ndukwe HC, Wang T, Tordoff JM, Croucher MJ, Nishtala PS. Geographic variation in psychotropic drug utilisation among older people in New Zealand. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(4):242–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12298.

Ministry of Health. Pharmaceutical collection (2017). Publicly funded pharmaceutical dispensings between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2016. Extraction date: 1 November 2017.

Ministry of Health. Pharmaceutical collection (2020). Publicly funded pharmaceutical dispensings between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2019 for a selected cohort. Extraction date: 10 March 2020.

Merlo J, Wessling A, Melander A. Comparison of dose standard units for drug utilisation studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50(1–2):27–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002280050064.

Statistics New Zealand. National population estimates: at 30 June 2021. https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/stats-infoshare. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Xu J, Hao Q, Qian R, Mu X, Dai M, Wu Y, et al. Optimal dose of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12: 717999. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.717999.

Bighelli I, Trespidi C, Castellazzi M, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Girlanda F, et al. Antidepressants and benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9(9):CD011567. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011567.pub2.

Patetsos E, Horjales-Araujo E. Treating chronic pain with SSRIs: what do we know? Pain Res Manag. 2016;2016:2020915. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2020915.

Crocco EA, Jaramillo S, Cruz-Ortiz C, Camfield K. Pharmacological management of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-017-0102-4.

Alexopoulos GS. Pharmacotherapy for late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(1): e04. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.7085tx2cj.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60046-5.

Behlke LM, Lenze EJ, Pham V, Miller JP, Smith TW, Saade Y, et al. The effect of venlafaxine on electrocardiogram intervals during treatment for depression in older adults. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(6):553–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcp.0000000000001287.

Scherf-Clavel M, Hommers L, Wurst C, Stonawski S, Deckert J, Domschke K, et al. Higher venlafaxine serum concentrations necessary for clinical improvement? Time to re-evaluate the therapeutic reference range of venlafaxine. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34(10):1105–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120936509.

Michelsen JW, Meyer JM. Cardiovascular effects of antipsychotics. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(7):829–39. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.7.7.829.

Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(Suppl. 1):1–93. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200519001-00001.

Jauhar S, Guloksuz S, Andlauer O, Lydall G, Marques JG, Mendonca L, et al. Choice of antipsychotic treatment by European psychiatry trainees: are decisions based on evidence? BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-12-27.

McKean A, Vella-Brincat J. Regional variation in antipsychotic and antidepressant dispensing in New Zealand. Australas Psychiatry. 2010;18(5):467. https://doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2010.502573.

Stargardt T, Edel MA, Ebert A, Busse R, Juckel G, Gericke CA. Effectiveness and cost of atypical versus typical antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of patients with schizophrenia in Germany. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(5):602–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e318268ddc0.

Trifirò G, Spina E, Gambassi G. Use of antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia: do atypical and conventional agents have a similar safety profile? Pharmacol Res. 2009;59(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2008.09.017.

Hálfdánarson Ó, Zoëga H, Aagaard L, Bernardo M, Brandt L, Fusté AC, et al. International trends in antipsychotic use: a study in 16 countries, 2005–2014. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):1064–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.07.001.

Carton L, Cottencin O, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Geoffroy PA, Favre J, Simon N, et al. Off-label prescribing of antipsychotics in adults, children and elderly individuals: a systematic review of recent prescription trends. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(23):3280–97. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612821666150619092903.

Bachmann CJ, Aagaard L, Bernardo M, Brandt L, Cartabia M, Clavenna A, et al. International trends in clozapine use: a study in 17 countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(1):37–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12742.

Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, Docherty JP. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl. 2):5–99 (discussion 100–2; quiz 3–4).

Juergens S. Alprazolam and diazepam: addiction potential. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1991;8(1–2):43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-5472(91)90026-7.

Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). Available from: https://pharmac.govt.nz/assets/schedule-dispatch-2016-12.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

Clay E, Falissard B, Moore N, Toumi M. Contribution of prolonged-release melatonin and anti-benzodiazepine campaigns to the reduction of benzodiazepine and Z-drugs consumption in nine European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1424-1.

Gunja N. In the Zzz zone: the effects of Z-drugs on human performance and driving. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(2):163–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-013-0294-y.

Nishtala PS, Chyou TY. Zopiclone use and risk of fractures in older people: population-based study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(4):368.e1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.085.

Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. 2009;10(Suppl. 1):S7-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.004.

Bjorvatn B, Meland E, Flo E, Mildestvedt T. High prevalence of insomnia and hypnotic use in patients visiting their general practitioner. Fam Pract. 2017;34(1):20–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw107.

Louzada LL, Machado FV, Nóbrega OT, Camargos EF. Zopiclone to treat insomnia in older adults: a systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;50:75–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.04.013.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Analytical Services, Ministry of Health of New Zealand, for supplying the data extracted from the Pharms database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was provided for the publication of this article.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Prasad S. Nishtala and Te-yuan Chyou have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Bath, UK (form number 7423).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data are owned by the Analytical Services, Ministry of Health NZ, and hence we cannot share raw data for this study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: PSN; statistical analysis: PSN, TC; interpretation of data: PSN, TC; drafting of the manuscript: PSN; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PSN, TC; study supervision: PSN. PSN and TC have read and approved the final submitted manuscript and agree to be accountable for the work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nishtala, P.S., Chyou, Ty. An Updated Analysis of Psychotropic Medicine Utilisation in Older People in New Zealand from 2005 to 2019. Drugs Aging 39, 657–669 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-022-00965-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-022-00965-8