Abstract

Introduction

One-third of adults in the USA experience chronic pain and use a variety of painkillers, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and opioids. However, some serious adverse events (AEs), such as cardiovascular incidents, overdose, and death, have been found to be related to painkillers.

Methods

We used 2015 and 2016 AE reports from the US FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) to conduct exploratory analysis on the demographics of those who reported painkiller-related AEs, examine the AEs most commonly associated with different types of painkillers, and identify potential safety signals. Summary descriptive statistics and proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) were performed.

Results

Out of over 2 million reports submitted to FAERS in 2015 and 2016, a total of 64,354 AE reports were associated with painkillers. Reports of opioid-associated AEs were more likely to be from males or younger patients (mean age 47.6 years). The highest numbers of AEs were reported for NSAID and opioid use, and the most commonly found AEs were related to drug ineffectiveness, administration issues, abuse, and overdose. Death was reported in 20.0% of the reports, and serious adverse reactions, including death, were reported in 67.0%; both adverse outcomes were highest among patients using opioids or combinations of painkillers and were associated with PRRs of 2.12 and 1.87, respectively.

Conclusions

This study examined the AEs most commonly associated with varying classes of painkillers by mining the FAERS database. Our results and methods are relevant for future secondary analyses of big data and for understanding adverse outcomes related to painkillers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A comparative study on adverse events associated with different classes of painkillers has not been conducted by data mining the US FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) (an existing post-marketing surveillance system). |

Opioid users with reported adverse events are more likely to be of male sex and of younger age than users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen with reported adverse events. |

Opioids or combined pharmacotherapy of different painkiller classes are more likely to be associated with serious and fatal adverse events. |

1 Introduction

Over 100 million American adults experience a form of chronic pain [1]. The most common forms are back pain, which affects 38 million people in the USA, and osteoarthritis, affecting 17 million Americans. In addition, patients with cancer, neuropathic diseases, migraines, and other chronic illnesses experience physical and mental disability and loss of quality of life due to pain [1]. Analgesic medications for pain relief can be divided into three classes: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen (or paracetamol), and opioids. Painkillers were one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in emergency room (ER) and physician visits in 2013 [2]. Ibuprofen, aspirin, acetaminophen, and morphine were among the top 15 drugs to be prescribed in the ER, with 16.5, 4.0, 11.4, and 7.8 million prescriptions, respectively [2].

NSAIDs are commonly used for mild pain and include drugs such as ibuprofen, aspirin, naproxen, and celecoxib. In 2010, roughly 29.4 million US adults were taking NSAIDs at least three times per week [3]. However, in recent years, some NSAIDs have been shown to be associated with adverse cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, and gastrointestinal events [4,5,6,7].

Another commonly used painkiller is acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol. It is one of the most common over-the-counter (OTC) analgesic drugs used for mild to moderate pain [8]. Although acetaminophen is available without a prescription, toxicity has been found to occur regularly at higher dosages (> 4 g per day) [9]. In addition, research has found that 21.8% of acetaminophen overdose deaths are unintentional [10].

Lastly, opioids, such as morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl, make up the third class of painkillers. While NSAIDs and acetaminophen are available OTC and are non-habit-forming painkillers, opioids are considered narcotics with the potential for addiction due to the associated euphoria and “emotional detachment from pain” [11]. The current opioid epidemic (an increase in both use of prescription opioids and fatal overdoses) has partially been associated with prescription opioid misuse and non-medical use and is a major public health concern in the USA. Opioid misuse has previously been associated with severe respiratory depression and death [12, 13], though it should be noted that such events can occur even when the medication is used as prescribed. In addition, increases in ER visits and hospital admissions have been correlated with concurrent use of opioids with other drugs such as benzodiazepines and psychotropic drugs [14, 15].

Adverse events (AEs), which are defined as “any undesirable experience associated with the use of a medical product in a patient” by the US FDA [16], are common with painkillers. AEs can include unintended side effects from using a drug, from using a drug incorrectly or in a manner different from prescribed directions, and from using drugs manufactured with poor quality; it also includes therapeutic failures when the intended effect from the medication is not achieved [17]. As shown above with different classes of painkillers, AEs can range from mild side effects to serious illness or death. AEs are common for both consumers of OTC painkillers and patients with prescriptions from hospitals and physician’s offices. AEs account for 1 million ER visits and 125,000 hospital admissions each year, and it has been reported that almost one-third of preventable AEs are associated with painkillers [1, 18].

While short-term side effects and AEs are oftentimes detected during clinical trials prior to FDA approval, long-term AEs are frequently detected through post-marketing surveillance systems such as the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) [17]. FAERS is a collection of reports of AEs by consumers, healthcare providers, drug manufacturers, and others; such reporting systems can be used for signal detection or the discovery of potential AEs. Several studies have examined specific AEs, such as cardiovascular events and overdose as mentioned above, with painkillers, but no comprehensive study has examined the different classes of painkillers and their commonly associated AEs concurrently. Using the publicly available FAERS database, we conducted a descriptive study on painkiller usage, examined the most commonly reported adverse outcomes associated with different types of painkillers, and identified signals for patient death or serious injury.

2 Methods

For this project, we conducted descriptive analyses on the most recently available FAERS data (1 January 2015 to 31 December 2016) through the FDA database (http://open.fda.gov/api). Queries to the FDA database were created using requests package in Python v2.7 with names of drugs under different painkiller classes as parameters [see Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) 1]. Queries were limited to AEs where the patient’s age and sex were known and where a painkiller drug was suspected as a cause of the AE (“drugcharacterization” variable = 1). Results were downloaded as JSON (http://www.json.org) files and managed in an SQLite database (http://www.sqlite.org). AEs related to NSAID usage were extracted, for example, if drug names “nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug”, “acetylsalicylic acid”, “aspirin”, and others as listed in the ESM 1 were found under the “medicinalproduct” variable. Drugs with both acetaminophen and opioid components or NSAID and opioid components were classified separately as “combination” drugs; this group also included patients who were taking more than one class of painkillers at the time of the AE. This fourth group “combination” was created only for statistical analysis to reflect the use of painkillers with multiple components or concurrent use of more than one class of painkillers. Since patients/consumers, healthcare providers, and pharmaceutical companies submit reports to the FAERS system, we attempted to de-duplicate these AE reports by dates of receipt and by report ID, but these measures may not have been sufficient if both parties reported AEs independently on separate dates.

We considered the following variables (with its corresponding database encoding): name of drug (“medicinalproduct”); whether it was the reported agent responsible for the AE (“drugcharacterization”); whether it caused death, hospitalization, congenital anomaly, or disability (“serious”); whether it resulted in death (“seriousnessdeath”); the patient’s age and sex (“patientonsetage” and “patientsex”); reason(s) why the patient was taking the drug (“drugindication”); and reaction(s) or AE(s) related to the drug (“reactionmeddrapt”). Reactions were coded by the FDA using MedDRA® (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) nomenclature, and patients’ ages were coded in years based on the “patientonsetageunit” variable.

All AEs associated with painkiller usage were analyzed; this included users of all ages and both sexes. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS v9.4 after exporting the SQLite database as comma-separated values files. We performed descriptive statistics stratified by classes of painkillers with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-squared test statistics to test significance. Most commonly found adverse reactions and drug indications were based on the frequency among AE reports. Proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) were calculated as shown in Bate and Evans [19] and Duggirala et al. [20]. For PRR of death and its association with different classes of painkillers, the proportion of fatal AEs for a single class of painkiller was divided by the proportion of fatal AEs for the other three classes of painkillers. A similar approach was used for serious reactions.

3 Results

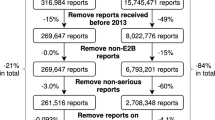

In 2015 and 2016, a total of 2,372,624 AE reports were submitted to the FDA. For 227,839 AE reports, painkillers were listed as one of the drugs a patient was taking at the time of an AE (see ESM 1 for a full list of painkiller drug names). After excluding reports in which a painkiller was not the suspected drug behind the AE and those without patient demographic information (sex and age), our final dataset included 64,354 AE reports.

Among our sample of 64,354 reports, 26,130 (40.6%) reports were associated with the use of NSAIDs, 4738 (7.4%) were attributed to acetaminophen, 18,696 (29.1%) to opioids, and 14,790 (23.0%) to the use of a combination of painkillers (Table 1). The mean age for these patients with AEs was 60.4, 50.0, 47.6, and 54.5 years, respectively, but the medians and age ranges of the patient population for each painkiller class varied (Fig. 1). More males than females tended to report AEs with opioids compared with acetaminophen (43.8 vs. 34.0%), but females contributed a higher overall proportion of AE reports (58.8%).

Seriousness of AE was designated by the FDA if the event resulted in death, threatened life, required hospitalization, led to short- or long-term disability, caused congenital anomaly or birth defect in pregnant women, required intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage, or led to other serious medical events [16]. Among reports related to acetaminophen usage, one-third were denoted as serious, but the majority of AEs attributed to NSAIDs (62.0%), opioids (71.0%), or some combination of these painkiller classes (79.5%) were reported as serious. Across all painkiller-related AE reports, death was reported in 20.0% of the reports and serious adverse reaction, which included death, was reported in 67.0%. Fatality was the highest for patients reporting AEs due to opioids and combination painkillers (32.0 and 31.2% of AEs vs. 6.4% for NSAIDs and 12.7% for acetaminophen). Combination drug users who reported AEs had the highest average number of adverse reactions per AE report (3.30) and reported the highest average number of concurrent medications (7.33). As shown in Table 1, multiple AEs were commonly reported for each report. These variables were all significantly different among the painkiller classes, with p values < 0.0001.

Over 5454 types of unique AEs were reported to be associated with painkillers (Fig. 2). On average, each AE report contained 3.00 reactions, but some reports contained as many as 110 reactions. The most frequently found AEs were ineffectiveness of the drug (found in 7.81% of all AE reports) and toxicity to various agents (6.96%). We found several AEs related to dosing and usage: “product use issue” (5.84%), “inappropriate schedule of drug administration” (2.23%), “incorrect dose administered” (2.15%), and “drug administered at inappropriate site” (1.34%). Pain was also commonly reported as an adverse reaction but ranged from pain at injection site to abdominal pain and headache. Figure 2 shows the top ten most frequent AEs for all painkillers, with each AE broken down by painkiller class. The frequency and the type of AEs differed by painkiller class (Table 2). Notably, gastrointestinal hemorrhage was the third most frequently found reaction with NSAIDs [n = 2482 (3.86%)], but it was not found as frequently for other classes of painkillers. Drug abuse, overdose, toxicity to various agents, and completed suicide were outcomes commonly found for AEs related to opioids and combinations of painkillers.

General pain was the most frequently reported indication for use of painkillers [n = 6513 (10.12% of study population)], but specific indications were also found, such as back pain (n = 2304) and arthritis (n = 2570). Additionally, several other indications such as drug dependence (n = 1066) and cancer pain (n = 209) for opioids are shown in Table 3.

We calculated PRRs to detect whether death or serious adverse reactions were associated with a specific class of painkillers (Table 4). A potential safety signal for opioids (PRR 2.12) and combination painkillers (PRR 1.87) was detected for death. Similarly, PRRs for serious adverse reactions was 1.09 for opioids and 1.26 for a combination of painkillers. Neither death nor serious adverse reactions were detected as potential safety signals with NSAIDs or acetaminophen (PRR < 1).

4 Discussion

Using FAERS, we found that a variety of painkiller-related AEs were reported between 2015 and 2016 (n = 64,354); among them were those related to NSAIDs (n = 26,130), acetaminophen (n = 4738), and opioids (n = 18,696) as well as combinations of these painkiller classes (n = 14,790). Individuals with AEs attributed to opioids were more likely to be male and younger. AEs associated with opioids were more likely to be serious than those related to NSAIDs or acetaminophen, and AEs were also highly likely to be serious and associated with death when pharmacotherapy was combined with the other two classes of painkiller drugs.

Patients using painkillers experienced AEs related to product use issues and drug ineffectiveness. Along with these outcomes, several AE reports also noted issues with dosage and administration, with drugs being administered on inappropriate schedules (n = 1436) and at inappropriate doses (n = 1384) among the top concerns reported to the FDA.

Similar to previous literature showing an association between NSAIDs and adverse cardiovascular events, we found 255 reports of chest pain (0.34% of NSAID-associated AE reports) and 209 reports of myocardial infarctions (0.28%) [4, 5]. We also found 417 reports of cardio-respiratory arrest and 410 respiratory arrests among opioid-related AEs [12].

When indication for the use of painkillers was examined, NSAID use was reported commonly as prophylaxis against cerebrovascular accidents (n = 6621). On the other hand, patients used acetaminophen most frequently for arthritic pain, general pain, and pyrexia. Since the FAERS database does not delineate which drug indication corresponds to which drug in the report, the reports included indications such as depression and anxiety, where a pain-relief regimen is not indicated for treatment. However, future work leveraging drug indications for other co-administered drugs at the time of AE as proxy for patient’s comorbidities may aid in understanding the complex interactions among pharmacotherapeutic regimens.

The data from FAERS have several limitations. First, a mix of generic and trade names of drugs appear in the FAERS database, and while a regular expressions package was used to address errors in capitalization and increase flexibility of search terms, AEs may have been excluded from our analysis because of spelling error. The comprehensive list of painkillers used in our queries was from the literature and from specific drug names listed under a drug indication of “pain”. We excluded medications taken to treat neuropathic pain since these neurologic therapies are inherently different from traditional painkillers in terms of pain-alleviating mechanism and pharmacodynamics. Additionally, these data did not confirm the designation of a specific drug as the cause of an AE. To our knowledge, these designations, as well as other parts of the AE report, have not been validated. Misclassification of outcomes is possible but is likely to be non-differential given that patients and providers are unlikely to report AEs differently based on the type of painkiller. We also noted a high frequency of incomplete reports; when we only considered reports with sex and age information, our sample size dropped by half. Drug indications were also often missing (n = 27,145).

In addition, FAERS is a spontaneous reporting surveillance system, and we cannot calculate incidence of AE or prevalence of drug use from this database. Therefore, we used PRRs of death and serious adverse reaction as outcomes of interest to comparatively study the different classes of painkillers and identify potential safety signals (Table 4). We found that opioids and combinations of painkillers were associated with both death and serious adverse reaction, whereas this potential safety signal was not found for NSAIDs or acetaminophen.

While the “Weber effect,” or the surge in reporting of AEs after a drug’s initial market release and publicity is a possible concern, the effect of this phenomenon has been found to be minor [21, 22]. The proportion of AE reports by types of painkillers remained steady during 2015–2016 (see ESM 2).

Despite these limitations, FAERS offers several advantages. The first of these is that over a decade of data are publicly available and can be used to assess drug-related AEs. In addition, the FDA has a direct stake in assessing the safety of drugs used in the USA and in reducing hospitalizations and other serious side effects; therefore, it is the most obvious agency to which AEs will be reported. Manufacturers are also required by law to report AEs to the FDA where they are made aware of these.

The annual societal cost of pain was estimated to be between 560 and 635 billion US dollars in 2008, which included direct costs of healthcare and indirect costs in loss of economic productivity [1]. While the cost of chronic pain is high for society, National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for pain research is a fraction of that amount (1.2% of total NIH budget) [23]. In addition to its prominence, FAERS is a publicly available database allowing interested researchers outside of the FDA to freely access large quantities of AE reports with comprehensive and systematic details regarding the events and their outcomes. Conducting research with a surveillance system already in place mitigates the costly burden of conducting new studies and allows rapid dissemination of scientific findings.

Our descriptive study on characteristics of painkiller users and AEs related to different classes of painkillers provides insight for physicians and pharmaceutical companies alike. Reducing the commonly reported AEs for each of these painkiller classes would be a common goal for all stakeholders involved in patient health. The information about AEs shown here can play a part in altering prescription and administration behaviors in ERs and outpatient settings.

5 Conclusions

Among AEs reported to the FAERS database, those associated with opioid painkillers were more frequently fatal and serious than AEs for NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Future work in data mining this publicly available resource on other drugs taken at the time of an AE may elucidate adverse reactions associated with interactions among a pharmacotherapy regimen.

References

Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC, National Academies Press; 2011. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/13172. Accessed 13 Mar 2017.

Center for Health Statistics N. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2013 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2017.

Zhou Y, Boudreau DM, Freedman AN. Trends in the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general US population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3463.

Gunter BR, Butler KA, Wallace RL, Smith SM, Harirforoosh S. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced cardiovascular adverse events: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42:27–38.

Varga Z, Rafay ali Sabzwari S, Vargova V. Cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: an under-recognized public health issue. Cureus. 2017;9:e1144.

Conaghan PG. A turbulent decade for NSAIDs: update on current concepts of classification, epidemiology, comparative efficacy, and toxicity. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1491–502.

Næsdal J, Brown K. NSAID-associated adverse effects and acid control aids to prevent them: a review of current treatment options. Drug Saf. 2006;29:119–32.

Hinz B, Cheremina O, Brune K. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in man. FASEB J. 2008;22:383–90.

Jozwiak-Bebenista M, Nowak JZ. Paracetamol: mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Pol Pharm Drug Res. 2014;71:11–23.

Nourjah P, Ahmad SR, Karwoski C, Willy M. Estimates of acetaminophen (paracetamol)-associated overdoses in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:398–405.

Ghelardini C, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Bianchi E. The pharmacological basis of opioids. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2015;12:219–21.

Fox LM, Hoffman RS, Vlahov D, Manini AF. Risk factors for severe respiratory depression from prescription opioid overdose. Addiction. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13925.

Garg RK, Fulton-kehoe D, Franklin GM. Patterns of opioid use and risk of opioid overdose death among medicaid patients. Med Care. 2017;55:661–8.

Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j760.

Boscarino JA, Kirchner HL, Pitcavage JM, Nadipelli VR, Ronquest NA, Fitzpatrick MH, et al. Factors associated with opioid overdose: a 10-year retrospective study of patients in a large integrated health care system. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:131–41.

US Food and Drug Administration. Reporting serious problems to FDA—what is a serious adverse event? Office of the Commissioner; 2016. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/howtoreport/ucm053087.htm. Accessed 27 Jun 2017.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse events reporting system (FAERS)—Reports received and reports entered into FAERS by year. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2014. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed 13 Mar 2017.

Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, Burdick E, Laird N, Petersen LA, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277:307–11.

Bate A, Evans SJW. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:427–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1742.

Duggirala HJ, Tonning JM, Smith E, Bright R a., Baker JD, Ball R, et al. Data mining at FDA. 2015;1–24. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/scienceresearch/dataminingatfda/ucm443675.pdf. Accessed 27 Jun 2017.

Wallenstein EJ, Fife D. Temporal patterns of NSAID the weber effect revisited. Drug Saf. 2001;24:233–7. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200124030-00006.

Hoffman KB, Dimbil M, Erdman CB, Tatonetti NP, Overstreet BM. The weber effect and the united states food and drug administration’s adverse event reporting system (FAERS): Analysis of sixty-two drugs approved from 2006 to 2010. Drug Saf. 2014;37:283–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-014-0150-2.

Gereau RW, Sluka KA, Maixner W, Savage SR, Price TJ, Murinson BB, et al. A pain research agenda for the 21st century. J Pain. 2014;15:1203–14.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, healthcare providers, and others who contribute to the FAERS database and the FDA for making these data publicly available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Conflicts of interest

Jae Min, Vicki Osborne, Allison Kowalski, and Mattia Prosperi have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Min, J., Osborne, V., Kowalski, A. et al. Reported Adverse Events with Painkillers: Data Mining of the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System. Drug Saf 41, 313–320 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0611-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0611-5