Abstract

Purpose

Our aim was to better explore the association between liver fibrosis (LF) and neurocognitive impairment (NCI) in people living with HIV (PLWH).

Methods

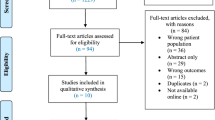

We performed a cross-sectional cohort study by consecutively enrolling PLWH at two clinical centers. All subjects underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological battery; NCI was defined as having a pathological performance (1.5 SD below the normative mean) on at least two cognitive domains. LF was explored using FIB4 index; in a subgroup of PLWH, LF was also assessed by transient elastography.

Results

A total of 386 subjects were enrolled, of whom 17 (4.4%) had FIB4 > 3.25. In the subgroup of PLWH (N = 127) performing also liver transient elastography, 14 (11%) had liver stiffness > 14 kPa. Overall, 47 subjects (12%) were diagnosed with NCI. At multivariate regression analyses, participants with FIB4 > 1.45 showed a higher risk of NCI in comparison with those with lower values (aOR 3.04, p = 0.044), after adjusting for education (aOR 0.71, p < 0.001), past AIDS-defining events (aOR 2.91, p = 0.014), CD4 cell count, past injecting drug use (IDU), HIV-RNA < 50 copies/mL, and HCV co-infection. Also a liver stiffness > 14 kPa showed an independent association with a higher risk of NCI (aOR 10.13, p = 0.041). Analyzing any single cognitive domain, a higher risk of abnormal psychomotor speed was associated with a liver stiffness > 14 kPa (aOR 223.17, p = 0.019) after adjusting for education (aOR 0.57, p = 0.018), HIV-RNA < 50 copies/mL (aOR 0.01, p = 0.007), age, past IDU, and HCV co-infection.

Conclusions

In PLWH, increased LF, estimated through non-invasive methods, was associated to a higher risk of NCI independently from HCV status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In people living with HIV (PLWH), both HIV-specific and non-specific factors can contribute to the expression of neurocognitive impairment (NCI). In this multifactorial model, the role of HCV co-infection is controversial [1, 2]. It has been suggested that HCV can promote NCI through its replication in the central nervous system (CNS), thus triggering neuroinflammation [3]. Moreover, HCV can determine liver inflammation with subsequent liver fibrosis (LF) and, possibly, slightly impaired liver function, which, in turn, might contribute to NCI by causing subclinical hepatic encephalopathy [4]. The contribution of LF to NCI has received limited research. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard in the assessment of LF [5]; however, biopsy is invasive, expensive, potentially associated with severe complications and subject to measurement error [6, 7]. These limitations led to the proliferation of non-invasive methods for LF measurement, which can be categorized into serum marker panels and imaging techniques [8]. A serum marker specifically developed for HIV/HCV co-infected patients is the FIB4, that has shown good accuracy in predicting LF [5]. However, the performance of transient elastography to detect fibrosis and cirrhosis among HIV/HCV co-infected patients appears superior to other previously validated and newly developed serum markers [8].

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between NCI and LF (estimated through non-invasive methods) in PLWH (both HIV mono-infected and HIV/HCV co-infected).

Methods

Subjects

We performed a cross-sectional study consecutively enrolling asymptomatic (without active opportunistic infections or other acute clinical conditions) PLWH during routine outpatient visits at two clinical centers (“Agostino Gemelli” Foundation, Rome, center 1; and “S. Caterina Novella” Hospital, Galatina, center 2). Exclusion criteria were: age < 18 years, decompensated liver disease, HCV treatment in the past 6 months, history of CNS opportunistic infections or other neurologic disorders, active psychiatric disorders, alcoholism or drugs abuse during the last 6 months, and non-native patients to avoid cultural bias at neuropsychological examination.

This study was approved by the local Institutional Ethics Committees (EC) at the two clinical centers and subjects provided written informed consent prior to enrollment (no. of EC protocol = 0005937/15).

At the time of the neuropsychological examination, the following data were collected through patients interview and chart review: gender, age, education, recent alcohol or drug abuse, risk factors for HIV infection, history of AIDS-defining events, current and past antiretroviral regimen, nadir and current CD4 cell count, HIV-1 plasma viral load, HCV co-infection (positive anti-HCV antibodies), AST and ALT levels, platelet count.

LF was estimated by FIB4 according to the standard formula [5]: age (years) × AST (IU/L)/platelet count (expressed as platelets × 109/L) × [ALT1/2(IU/L)]. As previously described [9], LF was categorized into three classes, corresponding to increased severity, based on the following cut-offs: FIB-4 ≤ 1.45 (mild fibrosis); FIB-4 from 1.46 to 3.25 (moderate fibrosis); FIB-4 > 3.25 (severe fibrosis/cirrhosis). PLWH enrolled at center 2 also underwent liver transient elastography by Fibroscan®; on the basis of liver stiffness cut-offs [10] LF was classified as follows: < 7 kPa (mild fibrosis); from 7 kPa through 14 kPa (moderate fibrosis); > 14 kPa (severe fibrosis/cirrhosis).

Neurocognitive evaluation

All subjects underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological battery exploring Memory [Immediate and Delayed Recall of Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT)], Attention (Forward digit span), Speed of psychomotor processing (WAIS-R Digit Symbol; Grooved Pegboard Test for both dominant and non dominant hand), and Language (Letter Fluency). Functional impairment was defined as a score < 7 at IADL scale.

Raw scores were z-transformed using means and standard deviations (SD) of Italian normative data [11,12,13] for all the cognitive measures but the cross-cultural Grooved Pegboard test [14]. NCI was defined as impairment in cognitive functioning in at least two domains according to Frascati criteria [15], with the only difference being a more severe definition of cognitive impairment (≤ 1.5 SD versus ≤ 1 SD below the normative mean). In fact, recent studies demonstrated approximately 15% false positive rate using a threshold of 1 SD [16, 17].

Statistical analyses

We used Student’s t test and the χ2 test or, when appropriate, Fisher’s exact test to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively, across study subgroups (i.e. HIV mono-infected vs HCV co-infected patients or center 1 vs centers 2 participants’ characteristics).

The association between NCI (globally and in each domain) and LF was investigated by a multivariate logistic regression model including only variables showing a significant (p < 0.05) correlation with NCI at univariate analyses. In addition, the model included “a priori” variables such as age and education, known to be associated with cognitive functioning [18,19,20], and HCV co-infection to explore the effect of LF independently by the co-infection. We performed two different models to explore the relation between LF and NCI. The first one included all study participants and LF was measured by FIB4 (model 1). In the second model, we restricted the analysis to the subset of participants performing the liver transient elastography (N = 127; model 2).

A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Overall, a total of 386 PLWH [306 (79.3%) males, median age 46 years (interquartile range, IQR 40–52), 75 (19.4%) with HCV co-infection, 141 (36.5%) past injecting drug users (IDU), 67 (17.4%) with past AIDS-defining events, 371 (96.1%) on antiretroviral therapy] were enrolled (Table 1).

Participants enrolled at center 1 (N = 259) and center 2 (N = 127) did not significantly differ on the main demographic and clinical variables (comparison included all the variables shown in Table 1), except for higher median education (years) (13 vs.10; p = 0.005), higher CD4 cell count (598 vs. 545; p = 0.006), higher proportion of past AIDS-defining events (22.0% vs. 7.9%; p = 0.001) and lower proportion of past IDU (15.2% vs. 31.5%; p < 0.001) in the first center compared to the second one.

Overall, 61 participants (15.8%) showed a moderate LF (FIB4 from 1.46 to 3.25), and 17 (4.4%) had a severe LF (FIB4 > 3.25); as expected, the proportion of severe LF was higher in HCV co-infected patients when compared to HIV mono-infected ones [14 (19%) vs. 3 (1%); p < 0.001].

In the subgroup of subjects performing Fibroscan® (N = 127), 21 (16.5%) and 14 (11%) had a liver stiffness 7–14 kPa (moderate LF) and > 14 kPa (severe LF), respectively; in this subgroup, 26 subjects (21%) had HCV co-infection and, similarly to the total sample population, the proportion of severe LF was higher in HCV co-infected people in comparison with HIV mono-infected patients [11 (42%)% vs. 3 (3%); p < 0.001].

Neurocognitive impairment

At neuropsychological examination, 41 subjects (12%) were diagnosed as affected by NCI. The most affected cognitive domains were verbal learning and attention with 18% and 15% of pathological performances, respectively (Table 2); no patient showed a significant functional impairment.

At multivariate analysis (Table 3, model 1), past AIDS-defining events [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 2.91; p = 0.014] and FIB4 > 1.45 (aOR 3.04; p = 0.021) were independently associated with higher risk of NCI, while higher education emerged as protective factor (aOR 0.71; p < 0.001). Other key factors such as HCV co-infection, CD4 cell count, past IDU, and suppressed plasma viremia (< 50 copies/mL) showed statistically significant associations only at univariate analysis.

Analyzing any single cognitive domains, we did not observe any independent association between FIB4 score and a specific abnormal cognitive area (data not shown).

In the subgroup of PLWH who received liver transient elastography assessment (N = 127), a liver stiffness > 14 kPa showed an independent association with higher risk of NCI (aOR 10.13, p = 0.041) (Table 3, model 2). Finally, in the multivariate model liver stiffness > 14 kPa was found to be associated with higher risk of abnormal psychomotor speed [aOR 223.17 when compared to stiffness < 7 kPa, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 2.40–20,737.03, p = 0.019], while higher levels of education (aOR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36–0.91, p = 0.018) and HIV-RNA < 50copies/mL (aOR 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.18, p = 0.007) emerged as protective factors, after adjusting for age (aOR 2.02 per 10 years increase, 95% CI 0.55–7.40, p = 0.290), past IDU (aOR 3.39, 95% CI 0.26–43.40, p = 0.349), and HCV co-infection (aOR 0.07, 95% CI 0.00–1.81, p = 0.108).

Discussion

We explored the relationship between LF and cognitive performance in PLWH. Our main finding was the association between moderate-severe LF (estimated by FIB4) and NCI independently by HCV status. Our data confirm a previous observation obtained using another non-invasive method (the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; APRI) [4]. The results of these two studies are consistent despite many differences in patients’ characteristics, as the higher proportion of PLWH with suppressed plasma viremia in our cohort (80% vs 40%); thus, the association between LF and NCI was confirmed in a well virologically-controlled HIV + cohort.

The association between increased LF and NCI was also confirmed in the subgroup of PLWH with fibrosis identified by liver transient elastography, a tool that has demonstrated good accuracy to detect LF, superior to the one of serum markers [21]. In this subgroup, we observed a significant association not only with global cognitive impairment, but also with lower scores on psychomotor speed, a function that relies especially on the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical circuit, according to previous observations in people with liver disease [22, 23] and to a recent study in PLWH [24].

Consistently with a prior study conducted on mono HIV-infected and HIV–HCV co-infected people [2], we observed a significant association between NCI and several HIV variables (past AIDS defining events and plasma viremia), but no with HCV co-infection. However, HCV co-infected patients appear at greater risk of NCI due to the highest burden of severe LF. NCI has been well documented in individuals with cirrhosis and attributed to molecules and toxins that accumulate in the blood and are not effectively cleared by the liver [25]. In our study, the finding of significant association between LF and NCI unlikely due to cirrhosis given the small number of participants with severe LF and the exclusion of individuals with decompensated liver diseases; this result is in line with previous evidence documenting the association between cognitive dysfunction and liver impairment in patients without cirrhosis [26].

We acknowledge that our study can have some limitations because the observational nature did not permit to establish causal relationships between factors, and there are possible uncontrolled biases. Moreover, only in one of the two study centers liver elastography by Fibroscan® was available.

In conclusion, our results provide further evidence that NCI in the setting of HIV infection might be associated with both HIV and non-HIV key factors including LF. Routine neuropsychological examinations in PLWH with multiple risk factors for neurodegeneration could help clinicians to better manage the cognitive evolution over time.

References

Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Grima P, et al. Comparison of cognitive performance in HIV or HCV mono-infected and HIV–HCV co-infected patients. Infection. 2013;41:1103–9.

Clifford DB, Vaida F, Kao YT, CHARTER Group, et al. Absence of neurocognitive effect of hepatitis C infection in HIV-coinfected people. Neurology. 2015;84:241–25.

Laskus T, Radkowski M, Adair DM, et al. Emerging evidence of hepatitis C virus neuroinvasion. AIDS 2005;Suppl 3:S140–4 (review).

Valcour VG, Rubin LH, Obasi MU, Womenʼs Interagency HIV Study Protocol Team, et al. Liver fibrosis linked to cognitive performance in HIV and hepatitis C. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72:266–73.

Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, APRICOT Clinical Investigators, et al. Development of a simple non-invasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317–25.

Poynard T, Ratziu V, Bedossa P. Appropriateness of liver biopsy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:543–8 (review).

Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495–500 (review).

Mehta SH, Buckle GC. Assessment of liver disease (non-invasive methods). Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:465–71.

Mendeni M, Focà E, Gotti D, et al. Evaluation of liver fibrosis: concordance analysis between non-invasive scores (APRI and FIB-4) evolution and predictors in a cohort of HIV-infected patients without hepatitis C and B infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1164–73.

Sanchez-Conde M, Montes-Ramirez ML, Miralles P, et al. Comparison of transient elastography and liver biopsy for the assessment of liver fibrosis in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients and correlation with non-invasive serum markers. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:280–6.

Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Gainotti G. The Mental Deterioration Battery: normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. The Group for the Standardization of the Mental Deterioration Battery. Eur Neurol. 1996;36:378–84.

Orsini A, Grossi D, Capitani E, Laiacona M, Papagno C, Vallar G. Verbal and spatial immediate memory span: normative data from 1355 adults and 1112 children. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1987;8:539–48.

Orsini A, Laicardi C. WAIS-R. Contributo alla taratura italiana. Firenze: Giunti OS; 1997.

Heaton RK, Grant I, Matthews CG. Comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead–Reitan battery: demographic corrections, research findings, and clinical applications. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1991.

Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–99.

Gisslén M, Price RW, Nilsson S. The definition of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: are we overestimating the real prevalence? BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:356.

Torti C, Focà E, Cesana BM, Lescure FX. Asymptomatic neurocognitive disorders in patients infected by HIV: fact or fiction? BMC Med. 2011;9:138.

Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii aging with HIV-1 cohort. Neurology. 2004;63:822–7.

Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Baldonero E, et al. Effect of aging and human immunodeficiency virus infection on cognitive abilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2048–55.

Milanini B, Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, et al. Cognitive reserve and neuropsychological functioning in older HIV-infected people. J Neurovirol. 2016;22:575–83.

Sebastiani G, Gkouvatsos K, Pantopoulos K. Chronic hepatitis C and liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11033–1153.

McCrea M, Cordoba J, Vessey G, Blei AT, Randolph C. Neuropsychological characterization and detection of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:758–63.

Lauridsen MM, Jepsen P, Vilstrup H. Critical flicker frequency and continuous reaction times for the diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a comparative study of 154 patients with liver disease. Metab Brain Dis. 2011;26:135–9.

Falasca K, Reale M, Ucciferri C, et al. Cytokines, hepatic fibrosis, and antiretroviral therapy role in neurocognitive disorders HIV related. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33:246–53.

Tarter RE, Edwards KL, Van Thiel DH. Neuropsychological dysfunction due to liver disease. In: Tarter RE, Van Thiel DH, Edwardsm KL, editors. Medical neuropsychology. New York: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 75–97.

Hilsabeck RC, Perry W, Hassanein TI. Neuropsychological impairment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;35:440–6.

Acknowledgements

No specific funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. F. received speakers’ honoraria and support for travel to meetings from Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), ViiV Healthcare, Janssen-Cilag (JC), and fees for attending advisory boards from BMS and Gilead; A.B. reports personal fees and non-financial support from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, Inc., grants and non-financial support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and JC. R.C. has been an advisor for Gilead, JC and Basel Pharmaceutical, and received speakers’ honoraria from ViiV, BMS, MSD, Abbott, Gilead and JC; S. D. G. received speakers’ honoraria and support for travel to meetings from Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag (JC) and GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors: none to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ciccarelli, N., Fabbiani, M., Brita, A.C. et al. Liver fibrosis is associated with cognitive impairment in people living with HIV. Infection 47, 589–593 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-019-01284-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-019-01284-8