Abstract

Top-down ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) allows greater sequence coverage than any other currently available method, often fracturing the vast majority of peptide bonds in whole proteins. At the same time, UVPD can be used to dissociate noncovalent complexes assembled from multiple proteins without breaking any covalent bonds. Although the utility of these experiments is unquestioned, the mechanism underlying these seemingly contradictory results has been the subject of many discussions. Herein, some fundamental considerations of photochemistry are briefly summarized within the context of a proposed mechanism that rationalizes the experimental results obtained by UVPD. Considerations for future instrument design, in terms of wavelength choice and power, are briefly discussed.

ᅟ

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) is not a new method to mass spectrometry, with the first experiments being reported decades ago [1,2,3]. However, it was only recently that UVPD began to attract significant attention when Shaw et al. [4] reported nearly complete sequence coverage of whole proteins in top-down experiments using this approach. There are several remarkable features of this result. First, large molecules, such as whole proteins, are difficult to fragment. For example, collision-induced dissociation (CID) works marvelously on smaller molecules such as peptides but is less useful for analysis of whole proteins, where facile cleavage at a handful of sites tends to dominate. This drawback can be partially compensated by increasing the collision energy (i.e., with higher-energy collisional dissociation [5]), but extensive fragmentation is still more difficult with increasing molecular size, and sequence coverage falls well short of being complete [6]. Electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) [7] and electron-capture dissociation (ECD) [8] also struggle to fragment whole proteins. Instead, abundant, intact, charge-reduced ions are often produced absent additional activation [9, 10]. These considerations naturally lead to an interesting question: Why does UVPD work so well on whole proteins?

Discussion

The obvious answer is that there must be something about UVPD that distinguishes it from all other fragmentation methods. With that in mind, let us explore what is known about ultraviolet photochemistry. Absorption of an ultraviolet photon leads to electronic excitation of a suitable chromophore. UVPD has been performed at several wavelengths, including 266 nm, 213 nm, 193 nm, and 157 nm. At 266 nm [11, 12], absorption in peptides occurs primarily at tyrosine and tryptophan side chains. At 193 nm [13, 14] and 213 nm [15], which correspond to higher-energy photons, excitation of the peptide backbone is also possible. At 157 nm [16], excitation of most bonds becomes feasible, including molecules in the air, requiring transmission of the laser beam in vacuo. Regardless of the excitation wavelength, once an excited-state electron is generated, there are two probable outcomes relevant to UVPD. First, if the electron is excited into or can relax into a dissociative orbital, then “direct” or “prompt” dissociation will occur [17, 18]. This type of fragmentation happens on a femtosecond timescale and is not preceded by energy redistribution or excitation of the remainder of the molecule. Well-documented examples of this type of chemistry include fragmentation of carbon–iodine, carbon–sulfur, and sulfur–sulfur bonds [19,20,21]. Indeed, direct dissociation is arguably a feature unique to UVPD, although proponents of the “nonergodic” mechanism [22] for ECD/ETD might argue otherwise.

A second relevant outcome following electronic excitation is internal conversion of the photon energy into vibrational modes. In this process, nonradiative relaxation back to the electronic ground state is accompanied by simultaneous vibrational excitation. The dictates of intramolecular vibrational energy redistribution (IVR) [23] allow this vibrational energy to be redistributed among all available modes within the femtosecond to picosecond timescale. The end result is a vibrationally hot molecule. If the photon energy is sufficient to cause dissociation via internal conversion, the fragments produced will be similar to those generated by CID or infrared multiphoton dissociation. In other words, regardless of whether energy is introduced by a collision or a photon, following IVR, the energy is randomized, and the expected fragmentation pathways should be the same. Importantly, even though a single photon may carry sufficient energy to break a particular covalent bond, this is not a likely outcome following internal conversion because the energy will rapidly disperse throughout the molecule because of IVR. For example, a 193-nm photon corresponds to 6.4 eV of energy, and a typical homolytic bond dissociation energy for a single bond would fall in the vicinity of approximately 3.5 eV [24]. Consequently, the amount of energy per mode will be very small in a large molecule such as a protein with hundreds of bonds [25]. Other relaxation pathways following electronic excitation, including fluorescence, are unlikely to yield dissociation.

We have identified the two dissociation mechanisms relevant to top-down UVPD: direct dissociation and internal conversion. Now we must ascertain how these work together to yield high sequence coverage. A weakness of direct dissociation is that little energy is available for the breaking of noncovalent bonds that may be holding the two fragments together. In a protein, many such intramolecular noncovalent interactions will be expected for compact or partially unfolded conformations. The resulting “stickiness” of these noncovalent bonds is often used to rationalize charge reduction without fragmentation in ETD/ECD [9]. Also relevant are experiments with disulfide-bound peptide pairs. Excitation of the disulfide bond leads to direct dissociation and observation of individual peptides. However, replacement of one peptide with propyl mercaptan significantly increases the photodissociation yield in some cases, suggesting that noncovalent interactions prevent some peptide dimers from falling apart [26]. Therefore, if direct dissociation alone were active in UVPD, low dissociation yields would be expected, but such behavior is not observed. A single laser pulse yields significant fragmentation [4]. It could be argued that perhaps UVPD initiates numerous direct dissociations, overcoming noncovalent bonding by effectively “shredding” the ion, but recent statistical analyses have demonstrated that multiple fragmentations are not dominant in UVPD [27].

On the other hand, if internal conversion were dominant, then UVPD and CID (or infrared multiphoton dissociation) spectra would be expected to be nearly identical. Although b/y ions are observed in UVPD, suggesting that internal conversion does contribute to the observed fragmentation, abundant a-, c- and z- type ions are also generated. These ions are unlikely to be produced by the mobile proton mechanism [28], which should dictate fragmentation following internal conversion. Therefore, internal conversion cannot rationalize all of the fragmentation observed in UVPD, but this is not to say that internal conversion does not play a significant role. The importance is highlighted best by a recent report on UVPD of tetrameric protein complexes [29]. In this application, UVPD leads to dissociation of whole protein dimers and monomers where the charge is distributed symmetrically among the products. By CID, these systems dissociate asymmetrically, ejecting a highly charged monomer [30]. The UVPD results closely mirror what is observed when protein complexes are fragmented by surface-induced dissociation (SID) [31]. The primary difference between SID and CID, in the context of this discussion, is the timescale. In SID, energy is deposited in a single, catastrophic event. By comparison, energy in CID is increased over a lengthy timescale involving many collisions. The similarity with SID suggests UVPD also facilitates rapid and substantial molecular heating, which most likely occurs via energy deposition from internal conversion of multiple photons over a short timescale (perhaps even shorter than in SID). This observation is critical for understanding how high sequence coverage is obtained in top-down UVPD experiments.

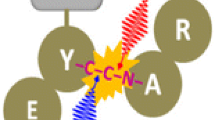

The body of these observations leads to a hypothesis—high sequence coverage in top-down UVPD results from simultaneous internal conversion and direct dissociation. The experiments with protein complexes reveal that significant internal conversion leads to rapid heating. The presence of non-proton-initiated fragments confirms direct dissociation also occurs. The simultaneous combination of both processes is required to rationalize the final results. Multiple photons are absorbed by the protein, and the majority undergo internal conversion, heating the ion. Simultaneously, a select few photons (probably less than one per protein) cause direct dissociation of the peptide backbone. Those fragments cleaved by direct dissociation then separate from each other due to heating from internal conversion. An illustration of the process is shown in Fig. 1. In some cases, internal conversion alone may be sufficient to fragment the molecule, leading to generation of some b/y ions. However, high sequence coverage is likely facilitated by the stochastic nature of peptide bond excitation that yields direct dissociation. In rare circumstances, a combination of dissociation events will lead to a secondary cleavage event, generating an internal ion and two terminal ions. For protein complexes, some of the proteins experience only internal heating, which leads to disruption of noncovalent bonds between subunits. Some proteins also undergo direct dissociation (which is also observed in reasonable abundance). The observation of intact protein dimers from tetramers and small abundance of internal ions both point to low incidence of direct dissociation (i.e., less than one direct dissociation per protein). Furthermore, recent experiments combining ultraviolet and infrared lasers demonstrated that the abundance of a-type ions did not increase significantly with additional infrared activation [32], suggesting that fragmented ions held together by noncovalent bonds are not abundant in UVPD.

Under the proposed mechanism, the ratio of internal conversion to direct dissociation events is important. If the fraction of direct dissociations is too high, then the ion will be shredded, and sensitivity will be negatively impacted by loss of ion current to internal ions. If the number of direction dissociations is too small, or zero, then sequence coverage will be reduced, and the results will begin to resemble those from CID. At 266 nm, single-photon direct dissociation of the peptide backbone is not possible because of lack of absorption. Direct dissociation becomes more feasible at 213 nm, and absorption by peptide bonds increases significantly at 193 nm, which may suggest greater access to direct dissociation pathways. For 157 nm, short timescale experiments have demonstrated abundant direct dissociation pathways in peptides [33]. Additional experiments will be required to determine which of these three ultraviolet wavelengths provides the optimal ratio of direct dissociation to internal conversion events. The incident power of the laser can also be varied, and may be important for instrument optimization. For example, the symmetric dissociation of protein complexes may be unlikely with a lower-power laser because of insufficient heating in an effectively short time-window.

Conclusions

UVPD is proving to be a versatile tool for interrogating whole proteins. Top-down sequencing can be achieved with excellent sequence coverage. Structural information can be obtained for proteins and protein complexes [34, 35]. Bond-selective fragmentation can be used to generate radicals for various purposes [36]. The ability to access dissociative excited states that yield fragments before IVR is a unique feature of UVPD. Improvements allowing greater control of these direct dissociation pathways will likely expand the capabilities of mass spectrometry even further.

References

Bowers, W. D., Delbert, S. S., Hunter, R. L. Jr, McIver, R. T. Fragmentation of oligopeptide ions using ultraviolet laser radiation and Fourier transform mass spectrometry. 106, 7288–7289 (2002).

Hunt, D.F., Shabanowitz, J., Yates, J.R.: Peptide sequence analysis by laser photodissociation Fourier transform mass spectrometry. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 8, 548 (1987)

Williams, E.R., Furlong, J.J.P., McLafferty, F.W.: Efficiency of collisionally-activated dissociation and 193-nm photodissociation of peptide ions in Fourier transform mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1(4), 288–294 (1990)

Shaw, J.B., Li, W., Holden, D.D., Zhang, Y., Griep-Raming, J., Fellers, R.T., Early, B.P., Thomas, P.M., Kelleher, N.L., Brodbelt, J.S.: Complete protein characterization using top-down mass spectrometry and ultraviolet photodissociation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135(34), 12646–12651 (2013)

Olsen, J.V., Macek, B., Lange, O., Makarov, A., Horning, S., Mann, M.: Higher-energy C-trap dissociation for peptide modification analysis. Nat. Methods 4(9), 709–712 (2007)

Sun, L., Knierman, M.D., Zhu, G., Dovichi, N.J.: Fast top-down intact protein characterization with capillary zone electrophoresis–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 85(12), 5989–5995 (2013)

Syka, J.E.P., Coon, J.J., Schroeder, M.J., Shabanowitz, J., Hunt, D.F.: Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101(26), 9528–9533 (2004)

Zubarev, R.A., Horn, D.M., Fridriksson, E.K., Kelleher, N.L., Kruger, N.A., Lewis, M.A., Carpenter, B.K., McLafferty, F.W.: Electron capture dissociation for structural characterization of multiply charged protein cations. Anal. Chem. 72(3), 563–573 (2000)

Lermyte, F., Williams, J.P., Brown, J.M., Martin, E.M., Sobott, F.: Extensive charge reduction and dissociation of intact protein complexes following electron transfer on a quadrupole-ion mobility-time-of-flight MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 26(7), 1068–1076 (2015)

Xia, Y., Han, H., McLuckey, S.A.: Activation of intact electron-transfer products of polypeptides and proteins in cation transmission mode ion/ion reactions. Anal. Chem. 80(4), 1111–1117 (2008)

Yeh, G.K., Sun, Q., Meneses, C., Julian, R.R.: Rapid peptide fragmentation without electrons, collisions, infrared radiation, or native chromophores. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 20(3), 385–393 (2009)

Park, S., Ahn, W.-K., Lee, S., Han, S.Y., Rhee, B.K., Bin. Oh, H.: Ultraviolet photodissociation at 266 nm of phosphorylated peptide cations. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 23(23), 3609–3620 (2009)

Morgan, J.W., Hettick, J.M., Russell, D.H.: Peptide sequencing by MALDI 193-nm photodissociation TOF MS. Methods Enzymol. 402, 186–209 (2005)

Moon, J.H., Yoon, S.H., Kim, M.S.: Photodissociation of singly protonated peptides at 193 nm investigated with tandem time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19(22), 3248–3252 (2005)

Girod, M., Sanader, Z., Vojkovic, M., Antoine, R., MacAleese, L., Lemoine, J., Bonacic-Koutecky, V., Dugourd, P.: UV Photodissociation of proline-containing peptide ions: insights from molecular dynamics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 26(3), 432–443 (2015)

Thompson, M.S., Cui, W., Reilly, J.P.: Fragmentation of singly charged peptide ions by photodissociation at λ=157 nm. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 43(36), 4791–4794 (2004)

Cheng, P.Y., Zhong, D., Zewail, A.H.: Kinetic-energy, femtosecond resolved reaction dynamics. modes of dissociation (in iodobenzene) from time-velocity correlations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 237(5–6), 399–405 (1995)

Zabuga, A.V., Kamrath, M.Z., Boyarkin, O.V., Rizzo, T.R.: Fragmentation mechanism of UV-excited peptides in the gas phase. J. Chem. Phys. 141(15), 154309 (2014)

Ly, T., Julian, R.R.: Residue-specific radical-directed dissociation of whole proteins in the gas phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130(1), 351–358 (2008)

Agarwal, A., Diedrich, J.K., Julian, R.R.: Direct elucidation of disulfide bond partners using ultraviolet photodissociation mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 83(17), 6455–6458 (2011)

Diedrich, J.K., Julian, R.R.: Facile identification of photocleavable reactive metabolites and oxidative stress biomarkers in proteins via mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 403(8), 2269–2277 (2012)

Breuker, K., Oh, H.B., Lin, C., Carpenter, B.K., McLafferty, F.W.: Nonergodic and conformational control of the electron capture dissociation of protein cations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101(39), 14011–14016 (2004)

Stannard, P.R., Gelbart, W.M.: Intramolecular vibrational energy redistribution. J. Phys. Chem. 85(24), 3592–3599 (1981)

Blanksby, S.J., Ellison, G.B.: Bond dissociation energies of organic molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 36(4), 255–263 (2003)

Marzluff, E.M., Beauchamp, J.L.: Collisional activation studies of large molecules. In: Baer, T. (ed.) Large Ions: Their Vaporization, Detection, and Structural Analysis, pp. 115–143. John Wiley and Sons, New York (1996)

Hendricks, N.G., Lareau, N.M., Stow, S.M., McLean, J.A., Julian, R.R.: Bond-specific dissociation following excitation energy transfer for distance constraint determination in the gas phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(38), 13363–13370 (2014)

Lyon, Y. A., Riggs, D., Fornelli, L., Compton, P. D., Julian, R. R. The ups and downs of repeated cleavage and internal fragment production in top-down proteomics. Submitted for publication.

Dongre, A.R., Jones, J.L., Somogyi, A., Wysocki, V.H.: Influence of peptide composition, gas-phase basicity, and chemical modification on fragmentation efficiency: evidence for the mobile proton model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118(35), 8365–8374 (1996)

Morrison, L.J., Brodbelt, J.S.: 193 nm ultraviolet photodissociation mass spectrometry of tetrameric protein complexes provides insight into quaternary and secondary protein topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(34), 10849–10859 (2016)

Jurchen, J.C., Williams, E.R.: Origin of asymmetric charge partitioning in the dissociation of gas-phase protein homodimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125(9), 2817–2826 (2003)

Zhou, M., Jones, C.M., Wysocki, V.H.: Dissecting the large noncovalent protein complex GroEL with surface-induced dissociation and ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 85(17), 8262–8267 (2013)

Halim, M.A., Girod, M., MacAleese, L., Lemoine, J., Antoine, R., Dugourd, P.: Combined infrared multiphoton dissociation with ultraviolet photodissociation for ubiquitin characterization. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 27(9), 1435–1442 (2016)

Thompson, M.S., Cui, W.D., Reilly, J.P.: Factors that impact the vacuum ultraviolet photofragmentation of peptide ions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 18(8), 1439–1452 (2007)

Warnke, S., von Helden, G., Pagel, K.: Analyzing the higher order structure of proteins with conformer-selective ultraviolet photodissociation. Proteomics 15(16), 2804–2812 (2015)

Morrison, L.J., Brodbelt, J.S.: Charge site assignment in native proteins by ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) mass spectrometry. Analyst 141(1), 166–176 (2016)

Ly, T., Julian, R.R.: Elucidating the tertiary structure of protein ions in vacuo with site specific photoinitiated radical reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132(25), 8602–8609 (2010)

Acknowledgement

The NIH is thanked for financial support (National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01GM107099).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

R. Julian, R. The Mechanism Behind Top-Down UVPD Experiments: Making Sense of Apparent Contradictions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 28, 1823–1826 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-017-1721-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-017-1721-0