Abstract

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common disorder diagnosed by the clinical characteristics of restlessness in the legs associated often with abnormal sensations that start at rest and are improved by activity, occurring with a diurnal pattern of worsened symptoms at night and improvement in the morning. RLS is the cause of impaired quality of life in those more severely afflicted. Treatment of RLS has undergone considerable change over the last few years. Several classes of medications have demonstrated efficacy, including the dopaminergic agents and the alpha-2-delta ligands. Levodopa was the first dopaminergic agent found to be successful. However, chronic use of levodopa is frequently associated with augmentation that is defined as an earlier occurrence of symptoms frequently associated with worsening severity and sometimes spread to other body areas. The direct dopamine agonists, including ropinirole, pramipexole, and rotigotine patch, are also effective, although side effects, including daytime sleepiness, impulse control disorders, and augmentation, may limit usefulness. The alpha-2-delta ligands, including gabapentin, gabapentin enacarbil, and pregabalin, are effective for RLS without known occurrence of augmentation or impulse control disorders, although sedation and dizziness can occur. Other agents, including the opioids and clonazepam do not have sufficient evidence to recommend them as treatment for RLS, although in an individual patient, they may provide benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a sensorimotor disorder diagnosed through subjective report of an urge to move the legs often associated with uncomfortable sensations that occur at rest and are partially or completely alleviated by movement. These symptoms follow a circadian pattern and occur predominantly in the late afternoon or evening (Table 1) [1] . RLS can be a primary disorder or secondary to an underlying cause (Table 2). There are several disorders in which the diagnostic criteria may be met but the patient does not have RLS (Table 3). Careful interview will usually result in distinguishing these disorders from RLS [2].

RLS is a common disorder, affecting approximately 2–3 % of the population with an increased frequency with advancing age, and is more common in women than men [3–6]. RLS can occur as a primary disorder, either familial or sporadic, or may arise secondary to a medical or neurological condition, including iron deficiency, uremia, or pregnancy. In more severe cases, RLS may delay sleep onset, resulting in a reduced number of hours of sleep and consequent daytime sleepiness, and negatively affects quality of life [4, 7]. RLS is associated with periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS), which is found in approximately 80 % of RLS. PLMS are diagnosed by polysomnography and are characterized by movements of one or both legs, typically as a flexion of one or more joints, including the hip and knee and dorsiflexion at the ankle. The movements are between 0.5 and 1.0 s in duration, and separated by a interval of 5–90 s [8]. PLMS may be associated with arousals, and can reduce the quality and quantity of nighttime sleep causing daytime sleepiness. If severe, PLMS can disrupt the sleep of the bed partner.

RLS is associated with high personal and social cost, as measured by productivity [3]. In addition, recent reports have suggested that RLS may be associated with a variety of comorbidities, including an increase risk of cardiovascular disease. In both cross-sectional [9] and large prospective studies [10, 11], the risk of cardiovascular disease was increased compared to that of non-RLS sufferers [9, 10]. Despite the possible increase in vascular disease, there was no increase in overall, all-cause mortality associated with RLS from a combined analysis of four studies that included almost 60,000 people [12].

In approximately 60 % of RLS patients, there is positive family history suggestive of an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, especially with a younger age at onset of RLS symptoms. However, the genetics of RLS are complex. There are several risk alleles found for RLS [13]. Variants in MEIS1, BTBD9, MAP2K5 / SKOR1, PTPRD, and TOX3 are associated with a significantly increased risk for RLS [13–17]. These alleles are in non-coding regions of the genes, and the metabolic pathways through which they confer the increased risk is only now being investigated.

The pathophysiology of RLS is unknown. In some patients with RLS there is a loss of iron in the substantia nigra, as measured using special magnetic resonance imaging parameters [18]. In contrast, in Parkinson disease, another dopamine-responsive disorder, there is an increase in iron in this area associated with a progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. In RLS there is no degeneration of dopaminergic neurons as shown by β-CIT single photon emission computed tomography measures of presynaptic dopamine binding [19, 20]. The alterations in central iron metabolism may not be present in all patients, suggesting that RLS is a heterogeneous disorder. Although RLS is very responsive to dopaminergic therapy (see ‘Treatment of RLS’ section), the role of dopamine has not been clarified. Changes in the dopaminergic neurons in the A11 region near the hypothalamus have been postulated, but no pathologic changes are found in this area in RLS [21, 22]. Alterations in cortical excitability and plasticity have been variably associated with RLS through the application of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Dopamine treatment has been demonstrated to normalize these changes [23, 24].

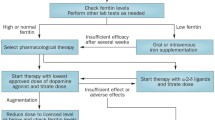

Treatment of RLS

The treatment of RLS must be individualized to each patient. A prior study demonstrated that application of specific treatment guidelines or algorithms in all patients may not be successful [25]. In patients with mild symptoms, no treatment may be required, although all patients should be screened for iron deficiency. In more severely afflicted patients with compromised sleep or impaired daytime functioning, treatment should be tailored to the particular circumstances of the individual patient.

Treatment of Secondary RLS

Following a diagnosis of RLS, the first step in designing a treatment strategy is to evaluate for secondary causes (Table 2) [26–28]. Iron deficiency is one of the most frequently associated causes. The most reliable indicator of body stores of iron is the serum ferritin, transferrin, and transferrin saturation. Prior studies have shown that lower ferritin levels correlate with increased severity of RLS [29] and that replacement of iron in iron-deficient RLS patients improves symptoms [30–32], although not all studies demonstrate similar findings [33]. The current recommendation is that all patients diagnosed with RLS be evaluated for iron deficiency. Those with low or low-to-normal ferritin levels, as determined by the specific values of the testing laboratory, should undergo iron replacement therapy, which can be done orally or parenterally. Oral iron replacement consists of 50–60 mg of elemental iron as a ferrous salt (sulfate, gluconate, or fumerate) twice a day supplemented with vitamin C to enhance absorption [27, 31, 34]. Serum ferritin levels should be monitored at 3-month intervals to avoid iron overload. The side effects of oral iron replacement may limit compliance, and mostly relate to the gastrointestinal system, including nausea, abdominal pain, and constipation. Parenteral iron replacement has also shown mixed outcomes in RLS. An open-label study in 25 RLS patients showed that high molecular weight iron dextran may be effective in a subset of patients (approximately 50 %), but at the risk of anaphylaxis [35]. Low molecular weight iron dextran was shown in a recent open-label study to improve RLS symptoms, and does not have the risk of anaphylaxis [30]. Other forms of parenteral iron, including ferric carboxymaltose appear to be safe and effective [36]. A controlled study of iron sucrose did not show benefit [37]. Parenteral iron replacement avoids the adverse effects of oral replacement, and may be effective for months following treatment. An important aspect of treating a patient with RLS and iron deficiency is to evaluate for the cause of the iron deficiency. This investigation may reveal underlying causes for chronic blood loss such as gastrointestinal cancers [38, 39].

In patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing dialysis, RLS is more frequent than in the general population, with a prevalence of approximately 20–60 %. The prevalence is almost 40 % in those with associated polyneuropathy [40]. Definitive treatment of end-stage renal failure associated RLS is kidney transplant [41, 42]. Pharmacologic interventions are based largely on treatments available for RLS in the non-renal failure patients [43], with the exception of those medications that are primarily cleared through renal mechanisms, and often provide suboptimal benefit.

A variety of medications are reported to exacerbate or trigger RLS symptoms. The most-cited class of drugs is the tricyclic antidepressants, the selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors, and the serotonin–norepinepherine reuptake inhibitors, including fluoxetine, paroxetine, duloxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine. This is based largely on clinical experience rather than prospective studies. Only one study followed 271 patients as they began a variety of these antidepressants. Overall, 9 % of the patients developed new or worsened RLS symptoms, with mirtazapine being the most frequently associated [44]. Most patients continued on the antidepressant because the symptoms were mild and were reduced over time. A cross-sectional study of 274 patients on antidepressants and referred to a sleep laboratory for polysomnography were compared to 69 patients without antidepressant therapy to evaluate PLMS. RLS was not included as an outcome of the study. This study showed significantly higher periodic limb movement index associated with treatment with the antidepressants, with the exception of buproprion [45]. A retrospective study in 200 patients presenting for insomnia found no association between antidepressant treatment and RLS [46]. For most patients with RLS, the standard recommendation is to avoid tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin–norepinepherine reuptake inhibitors, and to consider buproprion for the treatment of depression. However, given the lack of evidence, it is important to evaluate and treat each patient individually [27, 47].

Similarly, dopamine receptor antagonists have been implicated in the development or worsening of RLS. Given the beneficial role of dopaminergic agonist therapy for the treatment of RLS, this is a reasonable assumption. However, the evidence supporting this clinical observation is lacking. Based on expert clinical experience, it seems prudent to avoid dopamine antagonist drugs, including metoclopramide, in patients with RLS until prospective studies are done [27].

Additional drugs reported to cause or worsen RLS include the antihistamines, lithium, cimetadine, zonisamide, and sodium oxybate. These are case series or case reports. A review of drug-induced RLS has been recently published [48].

There are additional medical and neurologic conditions that have been associated with an increased frequency of RLS. These include neurological, medical, and psychiatric disorders (Table 2) [49].

Placebo Effect in RLS

When evaluating treatments for RLS, it is important to consider the robust placebo effect that occurs in this disorder. A meta-analysis of the placebo effect across 36 treatment studies (17 crossover studies and 19 parallel studies) was done, looking at the placebo effect on the variety of outcome measures used in these studies. Overall, approximately a third of patients treated with placebo had a major improvement in symptoms. The most prominent placebo effect was noted for the International Restless Leg Scale; in addition, there was a moderate effect for quality of life, with smaller placebo effects observed for daytime sleepiness, sleep quality, and total sleep time. The smallest placebo effects were observed in periodic limb movements in sleep. There was no placebo effect observed for sleep efficiency. Overall, the pooled placebo response rate was 40 % [50]. The magnitude of the placebo effect may be blunted in clinical trials where patients had previously been treated for RLS [51]. The placebo effect has not been well studied in RLS, but studies in other disorders suggest that it may be mediated by the dopaminergic or opioid systems in the brain [52]. The relevance of the placebo effect in clinical practice is not well understood. It may account for the benefit reported by patients from such modalities as a “bar of soap between the sheets”.

Nonpharmacologic Treatments for RLS

There are few studies that have evaluated nonpharmacologic treatments for RLS. A single controlled study evaluated the effect of progressive leg exercise in RLS patients over a 12-week study period. Although the study showed significant improvements in severity of RLS in the exercise group, the study was not blinded and only included 28 patients (11 in the exercise group and 17 in the control group) [53]. Other modalities that have been assessed in small, limited studies include yoga, acupuncture, and cognitive behavioral therapy and leg compressions [54–56]. Additional well-designed, controlled studies are needed.

Dopamine Agonists for RLS

Prior to 1980, treatment of RLS patients was very limited. In 1982, Akpinar [57] published his observations in 5 patients who had benefited from levodopa/benserazide. He also reported beneficial effects with bromocriptine [57]. This opened the door for a new era of therapeutic approaches to RLS. Subsequently, there were 9 controlled studies evaluating the efficacy of levodopa at doses ranging from 100 to 500 mg, but only in a limited number of patients (up to a maximum of 28) for a short period of time (up to 6 weeks) [58]. Although the outcome measures and study designs varied considerably among these studies and the results were mixed, many of these early studies found that levodopa provided significant subjective and objective benefit with few side effects. An open-label, 2-year follow-up study in 30 patients noted that 22 of them had sustained benefit [59]. Subsequently, response to levodopa or a direct dopamine agonist became one of the supporting criteria for the diagnosis of RLS [1], and a “levodopa test” for the diagnosis was developed [60], which showed a sensitivity of 80–90 % and a specificity of 100 %. However, this is not typically used for diagnosis, with the cardinal features being the major subjective criteria. Following these initial reports, long-term follow-up of patients showed recurrence of RLS symptoms in the morning (rebound) and the augmentation [61–63]. Augmentation refers to the worsening of RLS symptom severity from pretreatment levels following an initial benefit from the drug for most days of the week associated with an earlier onset of symptoms by at least 2–4 h, often associated with a shorter latency to RLS symptoms at rest, spread to other body areas, and increased intensity of symptoms [64]. Specific criteria have been developed that are useful in diagnosis, particularly for clinical studies [65, 66].

A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in 30 RLS patients with associated PLMS compared the addition of sustained-release levodopa (SR) to immediate-release (IR) levodopa. This study showed that the addition of SR levodopa resulted in improvement in RLS symptoms, reduced PLMS, increased time in bed, and improved subjective quality of sleep. However, during the 8-week study period, 17 % of patients noted that their RLS symptoms were now occurring in the afternoon [62]. The 1-year, open-label extension of this study showed that 60 % treated with either IR or SR levodopa developed daytime symptoms [67]. In a larger study of 60 RLS patients, the use of levodopa resulted in augmentation in 60 % after a median time of 71 days. This study showed that those who developed augmentation were on higher doses of levodopa and tended to have lower ferritin levels at baseline [68].

The observation that the efficacy of levodopa for RLS was offset by the occurrence of augmentation led to studies of longer-acting direct dopamine agonists. There are currently over 30 randomized, placebo-controlled studies and several published evidence-based reviews and meta-analyses of dopaminergic treatments for RLS [34, 69–74]. Overall, the direct dopamine agonists have been found to be effective in short- and longer-duration placebo-controlled studies for the treatment of RLS and PLMS. There have not been adequate comparative trials among the drugs available in this class to indicate whether one agent is superior to another [75]. Smaller studies indicate that the treatment effects are similar [76]. Because of the pharmacologic differences among these agents, it may be that reduced efficacy or adverse effects from one drug may improve with the substitution of another drug in this class in an individual patient. However, this has not been addressed by currently available studies.

The first direct dopamine agonists used for RLS were ergoline compounds. Bromocriptine was the first agonist found to improve RLS symptoms [57]. Most reports of benefit were observational with only a single small controlled study [77]. Pergolide was a second ergoline derivative that was found to be effective in 4 controlled studies that included up to 100 RLS patients [74], and was shown to be superior to levodopa in some studies [78]. Carbergoline is a long-acting ergoline derivative with an elimination half life of 65 h that has been evaluated in controlled studies and shown to be beneficial in RLS [79]. However, the use of ergoline compounds for RLS is not recommended owing to the adverse effects of this class of medications, including cardiac valve, retroperitoneal, pericardial, and pleuropulmonary fibrosis mediated through effects at the 5-hydroxytryptophan (HT)2B receptors.

There are 3 non-ergoline, direct dopamine agonists approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of RLS: ropinirole, pramipexole, and transdermal rotigotine (Table 4). Each of the compounds in this class has a very low affinity for the 5-HT2B receptors and is unlikely to be associated with the fibrosis seen in the ergoline class. Ropinirole hydrochloride was the first drug approved by the FDA, in 2005, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RLS. Ropinirole specifically stimulates the D3 receptors with lower affinity for D2 and very low affinity for D1 receptors. Ropinirole is metabolized through the liver and excreted through the kidney as inactive metabolites [75]. Ropinirole is available in an immediate release (IR) and extended-release (ER) formulation. No controlled studies have been published for the ER compound. Ropinirole IR has been evaluated in multiple randomized, placebo-controlled trials. These studies uniformly demonstrate that ropinirole is an effective treatment for RLS, improving RLS symptoms, sleep, and quality of life [80–84]. Improvement with ropinirole occurred approximately 1 week after the initiation of therapy. A placebo-controlled, polysomnographic study of the effects of ropinirole on sleep in RLS showed significant reduction in PLMS compared with placebo [83]. The most frequent side effects from ropinirole include nausea, fatigue, dizziness, and headache [80]. Based on a meta-analyses of the available controlled studies, ropinirole is recommended as standard treatment in which the “[b]enefits clearly outweigh harm” [71] and is supported by class 1 evidence [69]. The initial starting dose of ropinirole is 0.25 mg, and a dose range from 1.0 to 5.0 mg is the usual effective dose.

The consequences of sustained treatment with ropinirole for RLS were evaluated for up to 66 weeks [85]. In this study, the first 26-week period included 404 patients and was placebo-controlled. The second period included 269 patients who had completed the first period and was a 40-week, open-label extension using a dose range of ropinirole of 0.25–4.0 mg per day. Loss of benefit occurred in 13 % of patients during the first period and 16 % during the open-label period. Augmentation occurred in up to 4 % of patients over the entire study and was clinically meaningful in most [85].

Pramipexole is a non-ergoline compound approved for use in RLS by the FDA in 2006. Pramipexole has a high affinity, particularly for D3 receptors, and also has activity at D2 and D4 receptors with a low affinity for D1. In contrast to ropinirole, the metabolism of pramipexole is primarily through the kidney. Patients with significant renal impairment should be treated with lower doses [75]. Similar to ropinirole, pramipexole has both an IR and ER formulation. Only the IR has been evaluated for the treatment of RLS in published controlled trials. There are numerous, class 1 controlled studies of pramipexole. Based on these studies, pramipexole IR is recommended as standard therapy for RLS [71]. Most controlled studies are of limited duration. One longer, placebo-controlled study found that pramipexole continued to be effective throughout the 26-week study period. This study found that 9.2 % of pramipexole-treated patients developed augmentation compared with 6 % in the placebo arm [86]. Retrospective observations in pramipexole-treated RLS patients over longer time periods describe augmentation in 42 % at a median daily dose of 1 mg following a mean of 8 years of treatment. The augmentation symptoms were mild, and only 1 patient discontinued treatment for that reason. Additional findings from this study indicate that 56 % developed daytime sleepiness and 10 % developed impulse control disorders. There was a reduction in the number of patients who felt the drug was completely effective and approximately a quarter of the patients required an additional medication to control symptoms [87].

Rotigotine is a direct dopamine agonist with activity predominantly at the D2 receptor, but also at D1 and D3 receptors. It has B2 adrenergic receptor antagonist activity and 5-HT1a agonist activity. Rotigotine is available as a transdermal patch, providing steady-state plasma levels over 24 h. With removal of the patch, the terminal half-life is 5–7 h. Rotigotine is metabolized in the liver, but requires no dose adjustment unless there is severely impaired liver function [75]. The rotigotine transdermal patch has been evaluated in 16 randomized, placebo-controlled studies and found to be effective for RLS symptoms [72]. Based on Class 1 evidence, rotigotine has been found to be effective for the treatment of RLS [69] at doses between 1 and 3 mg. An open-label study evaluated the effect the rotigotine patch over 5 years. In this open-label extension of a placebo-controlled study, 43 % of 295 patients continued on the patch for 5 years at a mean dose of 3 mg per day, and 57 % discontinued treatment, mostly owing to adverse effects or lack of efficacy. The most frequent adverse event was an application site reaction that occurred within the first year of treatment. Over the 5-year period, 13 % of patients experienced clinically significant augmentation, resulting in discontinuation from the medication in 4 % [88]. A subsequent retrospective study confirmed the occurrence of augmentation with rotigotine [89].

Although the dopamine agonists differ pharmacologically, there are no studies that suggest that one agent is superior to another. The limiting feature of this class of drugs is the occurrence of side effects, in particular augmentation. During chronic administration of dopaminergic agents, a substantial number of patients develop augmentation. Augmentation is most common with the shorter-acting levodopa preparations, especially at higher doses treated for longer durations [68]. However, recent studies have shown that with longer duration treatment, augmentation occurs in up to 40 % of RLS patients treated with direct dopamine agonists [87]. Risk factors for augmentation include duration of dopaminergic therapy, more severe RLS symptoms, higher doses of dopaminergic drugs, older age, and reduced ferritin levels [90–92]. Treatment of augmentation can be challenging, with the best approach being prevention by keeping dopaminergic agents at low doses, and evaluating for reduced iron stores.

In addition to augmentation, other side effects associated with dopaminergic agents include excessive daytime sleepiness that is sometimes associated with falling asleep while driving, and impulse control disorders, including gambling, hypersexuality, and other behaviors atypical for a particular individual [93]. It is necessary to specifically interview patients regarding impulse control disorders and somnolence, and it is helpful if there are additional observers, such as a spouse or house partner, to further confirm the presence or absence of these adverse effects. If severe, reducing the dose or discontinuing the dopamine agonist is often required to reverse these adverse effects.

Alpha-2-delta Ligands for RLS

A second class of drugs that has demonstrated efficacy for RLS and PLMS is the alpha-2-delta ligands (Table 4), including gabapentin, gabapentin enacarbil, and pregabalin [69]. Only gabapentin enacarbil is FDA-approved for use in RLS. Gabapentin is a structural analog of gamma-aminobutyric acid that interacts with the α2δ-1 subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channels. Gabapentin enacarbil is a pro-drug of gabapentin that is absorbed by active transport in the gut and converted to gabapentin. Gabapentin enacarbil is more reliably absorbed than gabapentin, and the absorption is enhanced by the presence of food. Gabapentin is excreted largely unchanged through the kidney and requires dose adjustment for patients with significant renal insufficiency [75]. Gabapentin is usually started a dose of 300 mg in the evening. The time of dosing may be dependent on the time at which the RLS symptoms begin. The dose can be slowly escalated, usually on a weekly basis, until symptoms improve or side effects occur. Gabapentin enacarbil has been evaluated for use in RLS in both randomized, controlled studies and open-label observations for treatment durations from 2 weeks to 64 weeks. These studies have shown benefit for both RLS symptoms and PLMS [94–98]. In the longer-term studies, augmentation was not spontaneously reported, and the most frequent side effects from both compounds were somnolence and dizziness. A blinded, randomized study compared gabapentin (300 mg) to ropinirole (0.5 mg) on subjective measures of RLS and on sleep assessed using polysomnography. This study included 80 patients and found that gabapentin was superior to ropinirole in reducing sleep latency and efficiency, and increasing slow wave sleep, but both drugs had equally beneficial effects on PLMS [99].

Pregabalin binds to the α2δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels. It is actively transported across the gut and excreted unchanged in the urine. Pregabalin has not been approved by the FDA for use in RLS, although it has multiple approved indications for pain syndromes and epilepsy. There are 2 short-term studies providing class I evidence for efficacy for treating RLS. One study was a 6-arm, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study that evaluated 5 doses of pregabalin over a treatment duration of 6 weeks, and found that at a mean dose of 123.9 mg, there was 90 % efficacy. At higher doses of pregabalin (300 mg and 450 mg) there was improvement on some measures of severity, but adverse events were also more frequent [100]. Another short-term study of 12 weeks’ duration demonstrated that pregabalin at an approximate dose of 300 mg improved RLS symptoms and also improved sleep architecture. In addition, there was improvement in slow wave sleep and reduced wake time after sleep onset [101]. The most frequent side effects in both studies were sleepiness and unsteadiness or dizziness. Although no augmentation was observed in either study, longer duration studies are needed. In contrast to the typical doses used for pain syndromes, the dosing for RLS is lower, with the usual starting dose being 50 mg, and a slow titration to the optimal dose, often in the range of 150–300 mg per day. In RLS, pregabalin is given in the evening rather than divided doses throughout the day as it is for seizures or pain.

Other Pharmacologic Treatments for RLS

Early studies suggested that opioid compounds improved RLS symptoms [102, 103]. Long-term follow-up in 113 RLS patients treated with opioids showed that benefit could be sustained, and may improve symptoms in those failing dopaminergic therapies. However, the possibility of addiction to opioids and exacerbation of sleep apnea have limited the use of this class of drugs as a first-line therapy [104]. In those patients who are refractory to dopaminergic agents, methadone at a mean dose of 15 mg per day was beneficial [105]. A 10-year retrospective study found that 50 % of RLS patients treated with dopamine agonists discontinued these agents, but only 15 % of patients treated with methadone discontinued therapy. This study is limited by its retrospective design and the possible bias introduced by including patients who failed dopamine agonists in the methadone group [106]. A recent 12-week, placebo-controlled study evaluated a fixed dose combination drug, oxycodone–naloxone, administered twice a day in RLS patients who had failed previous treatments owing to lack of benefit or side effects. Patients were withdrawn from any current treatment for RLS prior to study entry. Two hundred and seventy-six patients were randomized to either placebo or oxycodone 5 mg–naloxone 2.5 mg twice a day and titrated up to either benefit or a maximal dose of oxycodone 40 mg–naloxone 20 mg twice a day. All patients then entered a 40-week open-label extension. This study demonstrated that in previously treatment-resistant RLS, oxycodone–naloxone was superior to placebo, and in the extension period, provided continued benefit for a median of 281 days at a mean dose of oxycodone 18.1 mg and naloxone 9.1 mg. Side effects from active treatment included fatigue, constipation, nausea, somnolence, and headache. Augmentation did not occur [107].

A variety of other medications has been used for the treatment of RLS. Clonazepam, although improving subjective sleep in some patients, did not reduce PLMS during the night [108] and has not been rigorously evaluated. Other medications likely efficacious but lacking sufficient evidence include carbamazepine, valproic acid, and clonidine [69, 74]. Additional treatments that have insufficient evidence include zolpidem, amantadine, botulinum toxin, buproprion, magnesium, vitamin E, folate, and vitamin B12 [74]. At this time, there is little evidence to support the use of these agents as a primary treatment for RLS.

Conclusion

RLS is a chronic disorder that can seriously impair quality of life. Several agents have sufficient evidence to be considered as effective for the treatment of RLS, including those approved by the FDA for RLS: ropinirole, pramipexole, rotigotine, and gabapentin enacarbil. However, the potential benefit of any drug used to treat RLS must be weighed against the acute and chronic adverse effects of the drug and the long-term consequences of therapy [7, 109].

References

Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med 2003;4:101–119.

Hening WA, Allen RP, Washburn M, Lesage SR, Earley CJ. The four diagnostic criteria for restless legs syndrome are unable to exclude confounding conditions ("mimics"). Sleep Med 2009;10:976–981.

Allen RP, Bharmal M, Calloway M. Prevalence and disease burden of primary restless legs syndrome: results of a general population survey in the United States. Mov Disord 2011;26:114–120.

Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, Hening W, Myers A, Bell TJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1286–1292.

Ohayon MM, O'Hara R, Vitiello MV. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: a synthesis of the literature. Sleep Med Rev 2012;16:283–295.

Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, John U, Kessler C. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:196–202.

Earley CJ, Silber MH. Restless legs syndrome: understanding its consequences and the need for better treatment. Sleep Med 2010;11:807–815.

Ferri R. The time structure of leg movement activity during sleep: the theory behind the practice. Sleep Med 2012;13:433–441.

Winkelman JW, Shahar E, Sharief I, Gottlieb DJ. Association of restless legs syndrome and cardiovascular disease in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Neurology 2008;70:35–42.

Li Y, Walters AS, Chiuve SE, Rimm EB, Winkelman JW, Gao X. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and coronary heart disease among women. Circulation 2012;126:1689–1694.

Winkelman JW, Redline S, Baldwin CM, Resnick HE, Newman AB, Gottlieb DJ. Polysomnographic and health-related quality of life correlates of restless legs syndrome in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep 2009;32:772–778.

Szentkiralyi A, Winter AC, Shurks M, Volzke H, Hoffmann W, Bruring JE, et al. Restless legs sndrome and all-cause mortality in four prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2012;2.

Freeman AA, Rye DB. The molecular basis of restless legs syndrome. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2013;23:895–900.

Winkelmann J, Polo O, Provini F, Nevsimalova S, Kemlink D, Sonka K, et al. Genetics of restless legs syndrome (RLS): State-of-the-art and future directions. Mov Disord 2007;22(Suppl. 18):S449-S458.

Yang Q, Li L, Chen Q, Foldvary-Schaefer N, Ondo WG, Wang QK. Association studies of variants in MEIS1, BTBD9, and MAP2K5/SKOR1 with restless legs syndrome in a US population. Sleep Med 2011;12:800–804.

Schormair B, Plag J, Kaffe M, Gross N, Czamara D, Samtleben W, et al. MEIS1 and BTBD9: genetic association with restless leg syndrome in end stage renal disease. J Med Genet 2011;48:462–466.

Winkelmann J, Czamara D, Schormair B, Knauf F, Schulte EC, Trenkwalder C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel restless legs syndrome susceptibility loci on 2p14 and 16q12.1. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1002171.

Allen RP, Barker PB, Wehrl F, Song HK, Earley CJ. MRI measurement of brain iron in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology 2001;56:263–265.

Eisensehr I, Wetter TC, Linke R, Noachtar S, von Lindeiner H, Gildehaus FJ, et al. Normal IPT and IBZM SPECT in drug-naive and levodopa-treated idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neurology 2001;57:1307–1309.

Michaud M, Soucy JP, Chabli A, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. SPECT imaging of striatal pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic status in restless legs syndrome with periodic leg movements in sleep. J Neurol 2002;249:164–170.

Ondo WG, Zhao HR, Le WD. Animal models of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2007;8:344–348.

Earley CJ, Allen RP, Connor JR, Ferrucci L, Troncoso J. The dopaminergic neurons of the A11 system in RLS autopsy brains appear normal. Sleep Med 2009;10:1155–1157.

Rizzo V, Arico I, Mastroeni C, Morgante F, Liotta G, Girlanda P, et al. Dopamine agonists restore cortical plasticity in patients with idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2009;24:710–715.

Scalise A, Pittaro-Cadore I, Janes F, Marinig R, Gigli GL. Changes of cortical excitability after dopaminergic treatment in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2010;11:75–81.

Godau J, Spinnler N, Wevers AK, Trenkwalder C, Berg D. Poor effect of guideline based treatment of restless legs syndrome in clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:1390–1395.

Rye DB, Trotti LM. Restless legs syndrome and periodic leg movements of sleep. Neurol Clin 2012;30:1137–1166.

Trenkwalder C, Paulus W. Restless legs syndrome: pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:337–346.

Salas RE, Gamaldo CE, Allen RP. Update in restless legs syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol 2010;23:401–406.

Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, Earley CJ, Allen RP. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep 1998;21:371–377.

Cho YW, Allen RP, Earley CJ. Lower molecular weight intravenous iron dextran for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2013;14:274–277.

Earley CJ. The importance of oral iron therapy in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2009;10:945–946.

Wang J, O'Reilly B, Venkataraman R, Mysliwiec V, Mysliwiec A. Efficacy of oral iron in patients with restless legs syndrome and a low-normal ferritin: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sleep Med 2009;10:973–975.

Trotti LM, Bhadriraju S, Becker LA. Iron for restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:CD007834.

Oertel WH, Trenkwalder C, Zucconi M, Benes H, Borreguero DG, Bassetti C, et al. State of the art in restless legs syndrome therapy: practice recommendations for treating restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2007;22(Suppl. 18):S466-475.

Ondo WG. Intravenous iron dextran for severe refractory restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2010;11:494–496.

Allen RP, Adler CH, Du W, Butcher A, Bregman DB, Earley CJ. Clinical efficacy and safety of IV ferric carboxymaltose (FCM) treatment of RLS: a multi-centred, placebo-controlled preliminary clinical trial. Sleep Med 2011;12:906–913.

Earley CJ, Horska A, Mohamed MA, Barker PB, Beard JL, Allen RP. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous iron sucrose in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2009;10:206–211.

Morcos Z. Restless legs syndrome, iron deficiency and colon cancer. J Clin Sleep Med 2005;1:433.

Brocklehurst J. Restless legs syndrome as a presenting symptom in malignant disease. Age Ageing 2003;32:234.

Gigli GL, Adorati M, Dolso P, Piani A, Valente M, Brotini S, et al. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease. Sleep Med 2004;5:309–315.

Kavanagh D, Siddiqui S, Geddes CC. Restless legs syndrome in patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;43:763–771.

Siddiqui S, Kavanagh D, Traynor J, Mak M, Deighan C, Geddes C. Risk factors for restless legs syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract 2005;101:c155-160.

de Oliveira MM, Conti CF, Valbuza JS, de Carvalho LB, do Prado GF. The pharmacological treatment for uremic restless legs syndrome: evidence-based review. Mov Disord 2010;25:1335–1342.

Rottach KG, Schaner BM, Kirch MH, Zivotofsky AZ, Teufel LM, Gallwitz T, et al. Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants. J Psychiatr Res 2008;43:70–75.

Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:510–514.

Brown LK, Dedrick DL, Doggett JW, Guido PS. Antidepressant medication use and restless legs syndrome in patients presenting with insomnia. Sleep Med 2005;6:443–450.

Hornyak M, Voderholzer U, Riemann D. Treatment of depression in patients with restless legs syndrome: what is evidence-based? Sleep Med 2006;7:301–302.

Hoque R, Chesson AL, Jr. Pharmacologically induced/exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and REM behavior disorder/REM sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6:79–83.

Frauscher B, Comella C. Sleep related movement disorders. In: Poewe W, Jankovic J (eds) Movement disorders in neurologic and systemic disease. Cambridge University Press, New York, (in press).

Fulda S, Wetter TC. Where dopamine meets opioids: a meta-analysis of the placebo effect in restless legs syndrome treatment studies. Brain 2008;131:902–917.

de la Fuente-Fernandez R. The powerful pre-treatment effect: placebo responses in restless legs syndrome trials. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:1305–1310.

Diederich NJ, Goetz CG. The placebo treatments in neurosciences: New insights from clinical and neuroimaging studies. Neurology 2008;71:677–684.

Aukerman MM, Aukerman D, Bayard M, Tudiver F, Thorp L, Bailey B. Exercise and restless legs syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med 2006;19:487–493.

Lettieri CJ, Eliasson AH. Pneumatic compression devices are an effective therapy for restless legs syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled trial. Chest 2009;135:74–80.

Eliasson AH, Lettieri CJ. Sequential compression devices for treatment of restless legs syndrome. Medicine 2007;86:317–323.

Innes K, Selfe T, Agarawal P, Williams K, Flack K. Efficacy of an eight-week yoga intervention on symptoms of restless legs syndrome (RLS): a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 2013;19:527–535.

Akpinar S. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with levodopa plus benserazide. Arch Neurol 1982;39:739.

Conti CF, de Oliveira MM, Andriolo RB, Saconato H, Atallah AN, Valbuza JS, et al. Levodopa for idiopathic restless legs syndrome: evidence-based review. Mov Disord 2007;22:1943–1951.

von Scheele C, Kempi V. Long-term effect of dopaminergic drugs in restless legs. A 2-year follow-up. Arch Neurol 1990;47:1223–1224.

Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Moller JC, Trenkwalder C, Oertel WH. Validation of the "L-DOPA test" for diagnosis of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2006;21:1333–1339.

Becker PM, Jamieson AO, Brown WD. Dopaminergic agents in restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements of sleep: response and complications of extended treatment in 49 cases. Sleep 1993;16:713–716.

Collado-Seidel V, Kazenwadel J, Wetter TC, Kohnen R, Winkelmann J, Selzer R, et al. A controlled study of additional sr-L-dopa in L-dopa-responsive restless legs syndrome with late-night symptoms. Neurology 1999;52:285–290.

Allen RP, Earley CJ. Augmentation of the restless legs syndrome with carbidopa/levodopa. Sleep 1996;19:205–213.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Williams AM. Dopaminergic augmentation of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:339–346.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Allen RP, Kohnen R, Hogl B, Trenkwalder C, Oertel W, et al. Diagnostic standards for dopaminergic augmentation of restless legs syndrome: report from a World Association of Sleep Medicine-International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group consensus conference at the Max Planck Institute. Sleep Med 2007;8:520–530.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Hogl B, Ferini-Strambi L, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Hornyak M, et al. Validation of the Augmentation Severity Rating Scale (ASRS): a multicentric, prospective study with levodopa on restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2007;8:455–463.

Trenkwalder C, Collado Seidel V, Kazenwadel J, Wetter TC, Oertel W, Selzer R, et al. One-year treatment with standard and sustained-release levodopa: appropriate long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome? Mov Disord 2003;18:1184–1189.

Hogl B, Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Ferini-Strambi L, Hadjigeorgiou G, Hornyak M, et al. Progressive development of augmentation during long-term treatment with levodopa in restless legs syndrome: results of a prospective multi-center study. J Neurol 2010;257:230–237.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Ferini-Strambi L, Kohnen R, O'Keeffe S, Trenkwalder C, Hogl B, et al. European guidelines on management of restless legs syndrome: report of a joint task force by the European Federation of Neurological Societies, the European Neurological Society and the European Sleep Research Society. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:1385–1396.

Hornyak M, Scholz H, Kohnen R, Bengel J, Kassubek J, Trenkwalder C. What treatment works best for restless legs syndrome? Meta-analyses of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic medications. Sleep Med Rev 2013 Jun 6 [Epub ahead of print].

Aurora R, Kristo D, Bista S, Rowley J, Zak R, Casey K, et al. The treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults-an update for 2012: practice parameters with an evidence-based systemic review and meta-analyses. Sleep 2012;35:1039–1062.

Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Ouellette J, Khawaja IS, Rutks I, Butler M, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for primary restless legs syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Int Med 2013;173:496–505.

Hornyak M, Trenkwalder C, Kohnen R, Scholz H. Efficacy and safety of dopamine agonists in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2012;13:228–236.

Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Montagna P, Oertel WH, Allen RP, Walters AS, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice. Mov Disord 2008;23:2267–2302.

de Biase S, Merlino G, Lorenzut S, Valente M, Gigli GL. ADMET considerations for restless leg syndrome drug treatments. Exp Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2012;8:1247–1261.

Manconi M, Ferri R, Zucconi M, Oldani A, Giarolli L, Bottasini V, et al. Pramipexole versus ropinirole: polysomnographic acute effects in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2011;26:892–895.

Walters A, Hening W, Kavey N, Chokroverty S, Gidro-Frank S. A double-blind randomized crossover trial of bromocriptine and placebo in restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol 1988;24:455–458.

Staedt J, Wassmuth F, Ziemann U, Hajak G, Ruther E, Stoppe G. Pergolide: treatment of choice in restless legs syndrome (RLS) and nocturnal myoclonus syndrome (NMS). A double-blind randomized crossover trial of pergolide versus L-dopa. J Neural Transm 1997;104:461–468.

Stiasny-Kolster K, Benes H, Peglau I, Hornyak M, Holinka B, Wessel K, et al. Effective cabergoline treatment in diopathic restless legs sydnrome. Neurology 2004;63:2272–2279.

Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, Lainey E, de Weerd AW, Tidswell P, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:92–97.

Walters AS, Ondo WG, Dreykluft T, Grunstein R, Lee D, Sethi K, et al. Ropinirole is effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. TREAT RLS 2: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord 2004;19:1414–1423.

Adler CH, Hauser RA, Sethi K, Caviness JN, Marlor L, Anderson WM, et al. Ropinirole for restless legs syndrome: a placebo-controlled crossover trial. Neurology 2004;62:1405–1407.

Allen R, Becker PM, Bogan R, Schmidt M, Kushida CA, Fry JM, et al. Ropinirole decreases periodic leg movements and improves sleep parameters in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep 2004;27:907–914.

Bogan RK, Fry JM, Schmidt MH, Carson SW, Ritchie SY, Group TRUS. Ropinirole in the treatment of patients with restless legs syndrome: a US-based randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:17–27.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Hogl B, Ferini-Strambi L, Winkelman J, Hill-Zabala C, Asgharian A, et al. Systematic evaluation of augmentation during treatment with ropinirole in restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom disease): results from a prospective, multicenter study over 66 weeks. Mov Disord 2012;27:277–283.

Hogl B, Garcia-Borreguero D, Trenkwalder C, Ferini-Strambi L, Hening W, Poewe W, et al. Efficacy and augmentation during 6 months of double-blind pramipexole for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2011;12:351–360.

Lipford MC, Silber MH. Long-term use of pramipexole in management of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2012;13:1280–1285.

Oertel W, Trenkwalder C, Benes H, Ferini-Strambi L, Hogl B, Poewe W, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of rotigotine transdermal patch for moderate-to-severe idiopathic restless legs syndrome: a 5-year open-label extension study. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:710–720.

Benes H, Garcia-Borreguero D, Ferini-Strambi L, Schollmayer E, Fichtner A, Kohnen R. Augmentation in the treatment of restless legs syndrome with transdermal rotigotine. Sleep Med 2012;13:589–597.

Allen RP, Ondo WG, Ball E, Calloway MO, Manjunath R, Higbie RL, et al. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) augmentation associated with dopamine agonist and levodopa usage in a community sample. Sleep Med 2011;12:431–439.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, Williams AM, Albares J, Pascual M, Palacios JC, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with pregabalin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology 2010;74:1897–1904.

Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, El-Demerdash E, Kaneider M, Rucker L, et al. The severity range of restless legs syndrome (RLS) and augmentation in a prospective patient cohort: association with ferritin levels. Sleep Med 2009;10:611–615.

Voon V, Schoerling A, Wenzel S, Ekanayake V, Reiff J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Frequency of impulse control behaviours associated with dopaminergic therapy in restless legs syndrome. BMC Neurol 2011;11:117.

Winkelman JW, Bogan RK, Schmidt MH, Hudson JD, DeRossett SE, Hill-Zabala CE. Randomized polysomnography study of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2011;26:2065–2072.

Lee DO, Ziman RB, Perkins AT, Poceta JS, Walters AS, Barrett RW, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with restless legs syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7:282–292.

Kushida CA, Becker PM, Ellenbogen AL, Canafax DM, Barrett RW, Group XPS. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of XP13512/GSK1838262 in patients with RLS. Neurology 2009;72:439–446.

Ellenbogen AL, Thein SG, Winslow DH, Becker PM, Tolson JM, Lassauzet ML, et al. A 52-week study of gabapentin enacarbil in restless legs syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol 2011;34:8–16.

Bogan RK, Bornemann MA, Kushida CA, Tran PV, Barrett RW, Group XPS. Long-term maintenance treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin enacarbil: a randomized controlled study. Mayo Clinic Proc 2010;85:512–521.

Saletu M, Anderer P, Saletu-Zyhlarz GM, Parapatics S, Gruber G, Nia S, et al. Comparative placebo-controlled polysomnographic and psychometric studies on the acute effects of gabapentin versus ropinirole in restless legs syndrome. J Neural Transm 2010;117:463–473.

Allen R, Chen C, Soaita A, Wohlberg C, Knapp L, Peterson BT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, 6-week, dose-ranging study of pregabalin in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2010;11:512–519.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Silber MH, Winkelman JW, Earley CJ, Hogl B, et al. The long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease: evidence-based guidelines and clinical consensus best practice guidance: a report from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med 2013;14:675–684.

Walters A, Wagner M, Hening W, Grasing K, Mills R, Chokroverty S, et al. Successful treatment of the idiopathic restless legs syndrome in a randomized double-blind trial of oxycodone versus placebo. Sleep 1993;16:327–332.

Hening W, Walters A, Kavey N, Gidro-Frank S, Cote L, Fahn S. Dyskinesias while awake and periodic movements in sleep in restless legs syndrome: treatment with opioids. Neurology 1986;36:1363.

Walters AS, Winkelmann J, Trenkwalder C, Fry JM, Kataria V, Wagner M, et al. Long-term follow-up on restless legs syndrome patients treated with opioids. Mov Disord 2001;16:1105–1119.

Ondo WG. Methadone for refractory restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2005;20:345–348.

Silver N, Allen RP, Senerth J, Earley CJ. A 10-year, longitudinal assessment of dopamine agonists and methadone in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2011;12:440–444.

Trenkwalder C, Benes H, Grote L, Garcia-Borreguero D, Hogl B, Hopp M, et al. Prolonged release oxycodone-naloxone for treatment of severe restless legs syndrome after failure of previous treatment: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:1141–1150.

Saletu M, Anderer P, Saletu-Zyhlarz G, Prause W, Semler B, Zoghlami A, et al. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD): acute placebo-controlled sleep laboratory studies with clonazepam. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001;11:153–161.

Chokroverty S. Long-term management issues in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2011;26:1378–1385.

Aurora RN, Kristo DA, Bista SR, Rowley JA, Zak RS, Casey KR, et al. The treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults-an update for 2012: practice parameters with an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analyses: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Sleep 2012;35:1039–1062.

Trenkwalder C, Paulus W, Walters AS. The restless legs syndrome. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:465–475.

Ferini-Strambi L, Manconi M. Treatment of restless legs syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2009;15(Suppl. 4):S65-S70.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 1.19 MB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Comella, C.L. Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome. Neurotherapeutics 11, 177–187 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-013-0247-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-013-0247-9