Abstract

Although CO is present in methanogenic environments, an understanding of CO metabolism by methanogens has lagged behind other methanogenic substrates and investigations of CO metabolism in non-methanogenic species. This review features studies on the metabolism of CO by methanogens from 1931 to the present. The pathways for CO metabolism of freshwater versus marine species are contrasted and the ecological implications discussed. The biochemistry and role of CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase in the pathway for conversion of acetate to methane and biosynthesis of cell carbon is presented. Finally, a proposal for the role of CO and primitive forms of the CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase in the origin and early evolution of life is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

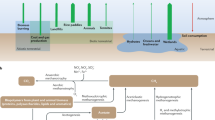

The decomposition of complex organic matter in diverse anaerobic environments is an essential link in the global carbon cycle (Fig. 1) producing approximately 1 billion metric tons of methane each year. In the cycle, CO2 is fixed into complex organic matter by photosynthesis that is decomposed primarily by O2-requiring aerobic microorganisms in oxygenated habitats with release of CO2 back into the atmosphere. However, a portion of the organic matter is also deposited in diverse O2-free habitats where anaerobic microbial food chains decompose the organic matter to CH4 and CO2 in a process called biomethanation. A portion of the CH4 is converted back to CO2 by anaerobic methylotrophs and the remainder escapes into aerobic zones where it is oxidized to CO2 by O2-requiring methylotrophs, thereby completing the global carbon cycle.

The global carbon cycle. a Fixation of CO2 into organic matter, b aerobic decomposition of organic matter to CO2, c anaerobic decomposition of organic matter to fermentative end products, d anaerobic conversion of fermentative end products to CH4, e anaerobic oxidation of CH4 to CO2, f aerobic oxidation of CH4 to CO2

The biomethanation of organic matter occurs in diverse habitats such as freshwater sediments, rice paddies, sewage digesters, the rumen, the lower intestinal tract of monogastric animals, landfills, hydrothermal vents, coastal marine sediments, and the subsurface (Liu and Whitman 2008). A minimum of three interacting metabolic groups of anaerobes comprise a consortium converting complex organic matter to CO2 and CH4 (Fig. 2). The fermentative group I anaerobes decompose complex organic matter to acetate, higher volatile fatty acids, H2, and CO2. The H2-producing acetogenic group II anaerobes decompose the higher volatile fatty acids to acetate, H2, and CO2. The group III and IV methanogens convert the metabolic products of the first two groups to CH4 by two major pathways. At least two-thirds of the CH4 produced in nature derives from the conversion of the methyl group of acetate by the Group III methanogens. The Group IV methanogens produce approximately one-third by reducing CO2 with electrons supplied from the oxidation of H2 or formate. Thus, methanogens are dependent on the first two groups to supply substrates for their growth. The production of H2 by Groups I and II is thermodynamically unfavorable, requiring the CO2-reducing methanogenic Group IV to maintain low concentrations of H2. A variety of other simple compounds serve as minor substrates for methanogenesis. Ethanol and secondary alcohols are used as electron donors for the reduction of CO2 to CH4. The methyl groups of methanol, methylamines, and methylated sulfides are also dismutated to CO2 and CH4. Although CO is present in methanogenic environments (Conrad and Seiler 1980), an understanding of CO metabolism by methanogens has lagged behind other substrates. This review chronicles studies on the metabolism of CO by methanogens from 1931 to the present. For a more comprehensive general understanding of methanogens, the reader is referred to several recent review articles describing the ecology, physiology, and biochemistry of methanogenesis (Ferry 2008; Ferry and Lessner 2008; Liu and Whitman 2008; Oelgeschlager and Rother 2008; Spanheimer and Muller 2008; Thauer et al. 2008).

A freshwater anaerobic microbial food chain. By permission (Ferry 2008)

CO as an energy source

The first recorded report portending the ability of methanogens to metabolize CO appeared in 1931 when it was demonstrated that sewage sludge converts CO to CO2 and CH4 (Fischer et al. 1931). However, the direct conversion of CO by methanogens (Eq. 1) could not be concluded since both H2 and acetate appeared and disappeared (Fischer et al. 1932) consistent with non-methanogens as the primary anaerobes metabolizing CO to methanogenic substrates (Eqs. 2 and 3).

In 1933, it was reported (Stephenson and Stickland 1933) that a pure culture was able to convert CO to CH4 by first converting CO to H2 (Eq. 2ab) that, 14 years later in 1947, was confirmed with resting cell suspensions of a pure culture (Kluyver and Schnellen 1947). Another gap in time had passed before studies on CO metabolism by methanogens resumed in 1977 and 1984 when it was shown that several species remove CO from the gas phase when growing with CO2 plus H2 and, for the first time, that two freshwater methanogens are able to grow with CO as the sole energy source, albeit under conditions unable to sustain proliferation in the native environment (Daniels et al. 1977). Only recently, a marine species was shown to grow with CO under conditions suitable for proliferation in the native environment via a novel pathway for methanogenesis consistent with CO-dependent growth in the native environment (Lessner et al. 2006).

Freshwater environments

Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus (formerly, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum strain ΔH) was shown to grow with CO as the sole energy source disproportionating CO according to Eq. 1, although the growth rate was only 1% of that with H2/CO2 (Daniels et al. 1977). Cell-free extracts showed CO dehydrogenase activity with coenzyme F420 as the electron acceptor. The activity was reversibly inactivated by cyanide and O2 consistent with an active-site metal center; however, the enzyme was not purified and studied in greater detail.

Methanosarcina barkeri strain MS isolated in 1966 (Bryant and Boone 1987) can be adapted to grow in an atmosphere of 50% CO as the only carbon and energy source (O'Brien et al. 1984). Net H2 formation is observed when the headspace CO is greater than 20%. Below this concentration of CO, H2 is consumed and the rate of CH4 production increases substantially with an increased growth rate approaching a doubling time of 65 h. Methanosarcina barkeri strain MS also produces CH4 and CO2 with the growth substrates methanol plus a headspace of 50% CO (O'Brien et al. 1984). However, it was reported that H2 accumulated and methanol was not metabolized until the CO decreased to below 30% in the headspace, at which point H2 and methanol was rapidly consumed proportional to an increase in the rate of CH4 formation and growth. Based on these characteristics, it was concluded that methanogenesis in the freshwater species M. barkeri strain MS is inhibited by concentrations of CO greater than approximately 50% in the headspace, consistent with results obtained with M. thermoautotrophicum (Daniels et al. 1977). The authors speculate that CO is metabolized according to Eqs. 2a and b, and the inhibition results from inhibition of hydrogenase catalyzing the oxidation of H2 (O'Brien et al. 1984). Although the pathway for reduction of CO2 to CH4 with H2 was not investigated, it is presumed to follow the well-studied pathway determined for freshwater methanogens, as shown in Fig. 3 for Methanosarcina species, with one possible exception. With H2 as the electron donor, the EchA-F (Escherichia coli-type hydrogenase) complex oxidizes H2 and reduces ferredoxin in reaction 1 (Fig. 3) that supplies electrons for reaction 2. The EchA-F complex is necessary, since the reduction of CO2 with H2 (reactions 1 plus 2) is thermodynamically unfavorable under standard conditions of one atmosphere H2 (ΔG°′ = +16 kJ/mole) and considerably more so with the much lower concentrations of H2 in the environment. This thermodynamic barrier is overcome by reverse electron transport to ferredoxin driven by the electrochemical proton gradient and catalyzed by the EchA-F hydrogenase complex. However, when cultured with CO, it is presumed that ferredoxin is the electron acceptor of the CO dehydrogenase and the oxidation of CO coupled to reduction of CO2 (reaction 2) becomes thermodynamically favorable (ΔG°′ = −4 kJ/mole) (Ferry and House 2006) obviating the requirement for EchA-F hydrogenase (Stojanowic and Hedderich 2004).

Marine environments

Recent investigations of Methanosarcina acetivorans demonstrate that this marine isolate displays robust growth with CO as the sole carbon and energy source (Lessner et al. 2006; Rother et al. 2007). The generation time (∼20 h) is less than that reported for other methanogens, and growth occurs with CO concentrations greater than 1 atmosphere. Although a few methanogens have been shown to utilize CO for growth, the experiments have routinely utilized concentrations above 50% in the atmosphere which is several-fold greater than is likely encountered in the environment. The lowest concentrations that support growth have not been reported for any methanogen, nor has a measurement of CO concentrations in the native habitats. Thus, a role for CO as the sole carbon and energy source in the native habitats of methanogens is still in question. Nonetheless, M. acetivorans was isolated from sediments rich in decaying kelp appended with flotation bladders containing up to 10% CO as a potential source of CO for growth of this marine isolate (Abbott and Hollenberg 1976; Sowers et al. 1984).

A biochemical and quantitative proteomic analysis of methanol- and acetate-grown versus CO-grown M. acetivorans (Lessner et al. 2006) has provided, for the first time, evidence of a pathway for CO-dependent methanogenesis supporting growth (Fig. 4) that has been confirmed in part by a qualitative proteomic analysis (Rother et al. 2007). In the pathway, 3 CO are oxidized to 3 CO2 that provides electrons for the subsequent reduction of 1 CO2 to form a methyl group attached to the cofactor tetrahydrosarcinapterin (THSPt) (reactions 1–6) similar to the pathway of freshwater methanogens (Fig. 3) except the electron donor. The methyl group of methyl-THSPt is transferred to coenzyme M (HS-CoM), although the route may be different from freshwater strains. The methyltransferase that transfers the methyl group from methyl-THSPt to HS-CoM (MtrA-H) in all known methanogenic pathways is down-regulated in CO-grown M. acetivorans versus methanol- and acetate-grown cells (Lessner et al. 2006) suggesting a reduced involvement of MtrA-H in the pathway (reaction 8, Fig. 4). The MtrA-H complex is membrane-bound and couples the methyl transfer reaction to translocation of sodium from the cytoplasm across the membrane to the periplasm, forming a gradient (Gottschalk and Thauer 2001). Indeed, the sodium requirement for methanogenesis is thought to originate from this enzyme, and the sodium gradient is postulated to drive energy-requiring reactions (Gottschalk and Thauer 2001). Three homologs annotated as putative corrinoid-containing proteins are up-regulated in CO-grown versus methanol- and acetate-grown M. acetivorans consistent with a role during growth with CO (Rother et al. 2007). Corrinoid cofactors bind the methyl group in a variety of methyltransferases from methanogens including the MtrA-H complex (Gottschalk and Thauer 2001); thus, it has been postulated (Lessner et al. 2006) that the up-regulated corrinoid proteins participate in transfer of the methyl group from methyl-THSPt to HS-CoM via a soluble sodium-independent pathway (reaction 7, Fig. 4) distinct from MtrA-H. In fact, one of the homologs overproduced in Escherichia coli (MA4384) catalyzes transfer of the methyl group from methyl-THSPt to HS-CoM (unpublished) supporting the proposal. The proposal does not rule out that both pathways may function simultaneously. Indeed, it is conceivable that both sodium-dependent MtrA-H and the postulated soluble sodium-independent pathway are required to accommodate variations in the energy available to pump sodium. Thus, at low environmental CO concentrations, the available energy is low and the transfer from methyl-THSPt to HS-CoM would necessarily shift more towards the sodium-independent pathway. With increased CO levels and greater available energy, methyl transfer would shift to the sodium-pumping MtrA-H complex to optimize the thermodynamic efficiency. Under laboratory conditions where cells are routinely cultured with greater than 0.5 atmosphere of CO, the postulated soluble sodium-independent route may be dispensable. The mechanism for providing electrons for reductive demethylation of CH3-S-CoM to CH4 is a prominent characteristic of the proposed pathway for conversion of CO to CH4 in M. acetivorans that further distinguishes it from the well-characterized CO2 reduction pathway of freshwater methanogens. In freshwater species of Methanosarcina, HS-CoB donates electrons for the reductive demethylation of CH3-S-CoM to CH4 catalyzed by methylreductase (reaction 10, Fig. 3). The heterodisulfide CoM-S-S-CoB is also a product of reaction 10 that is reduced to the active sulfhydryl forms of the cofactors catalyzed by the VhoACG/HdrDE complex (reaction 11, Fig. 3). H2 is oxidized by the VhoACG hydrogenase with transfer of electrons to the heterodisulfide reductase HdrDE that is coupled to formation of an electrochemical potential that drives ATP synthesis (reaction 12, Fig. 3). On the other hand, the proteomic and biochemical evidence indicates that HdrDE and the FpoA-O complex (F420H2 dehydrogenase) participate in the transfer of electrons to the heterodisulfide in M. acetivorans (reaction 10, Fig. 4). HdrDE and the FpoA-O complex also function in the pathway of methanol conversion to methane in Methanosarcina species (Ferry and Kastead 2007), including M. acetivorans (Li et al. 2007), wherein methanophenazine mediates electron transfer between FpoA-O and HdrDE. Methanophenazine is a quinone-like compound that translocates protons from the cytoplasm to the periplasm forming an electrochemical potential that drives ATP synthesis. Additionally, FpoA-O pumps protons contributing to the electrochemical potential in methanol-grown Methanosarcina species. Thus, it is postulated (Lessner et al. 2006) that the FpoA-O/HdrDE complex contributes to the electrochemical potential that drives ATP synthesis in CO-grown M. acetivorans (Fig. 4). The mechanism for the formation of formate is not known.

The products acetate and formate are yet another feature of the pathway in M. acetivorans that contrasts with M. barkeri (Rother and Metcalf 2004; Lessner et al. 2006; Oelgeschlager and Rother 2009). Quantitative proteomic analyses (Lessner et al. 2006) suggest a pathway in which CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase (CdhA-E) catalyzes synthesis of acetyl-CoA from the methyl group of methyl-THSPt, CO, and CoA-SH (reaction 11, Fig. 5). The acetyl-CoA is further converted to acetate catalyzed by phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase (reactions 12 and 13) with the synthesis of ATP. Thus, it appears that ATP is synthesized via both substrate level and chemiosmotic mechanisms. The CdhA-E complexes from freshwater Methanosarcina species have CO dehydrogenase activity with ferredoxin as the electron acceptor (Terlesky and Ferry 1988b), as does the M. acetivorans enzyme (unpublished results) consistent with the CdhA-E also functioning in steps 1a and 1b (Fig. 4). Quantitative RTPCR analysis indicates modest up-regulation of two genes annotated as encoding CooS in CO-grown versus acetate-grown cells (Lessner et al. 2006). CooS is a CO dehydrogenase first described in Rhodospirillum rubrum (32) that also reduces ferredoxin; thus, the putative CooS in M. acetivorans is also a candidate for catalyzing reactions 1a and 1b. Phenotypic analyses of mutant strains of M. acetivorans deleted of the cooS genes suggest they contribute to but are not required for CO-dependent growth (Rother et al. 2007). There are no known enzymes in M. acetivorans responsible for reactions leading from CO to coenzyme F420.

Pathway for the conversion of acetate to methane by Methanosarcina acetivorans. Ack Acetate kinase, Pta phosphotransacetylase, CoA-SH coenzyme A, THMPT tetrahydromethanopterin, Fd r reduced ferredoxin, Fd o oxidized ferredoxin, Cdh CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase, CoM-SH coenzyme M, Mtr methyl-THMPT:CoM-SH methyltransferase, CoB-SH coenzyme B, Cam carbonic anhydrase, Ma-Rnf M. acetivorans Rnf, MP methanophenazine, Hdr-DE heterodisulfide reductase, Mrp multiple resistance/pH regulation Na+/H+ antiporter, Atp H+-transporting ATP synthase. Carbon transfer reactions are catalyzed by the enzymes shown in blue. Electron transfer reactions are catalyzed by enzymes shown in green. By permission (Li et al. 2006)

Notably, H2 is not an intermediate in the pathway for CO conversion to CH4 in M. acetivorans (Lessner et al. 2006) in contrast to freshwater M. barkeri (Fig. 3). Indeed, M. acetivorans does not encode a functional EchA-F hydrogenase (Galagan et al. 2002). Thus, the observation that M. acetivorans is more tolerant of high concentrations of CO compared with M. barkeri is consistent with the postulated CO inhibition of hydrogenase in M. barkeri (O'Brien et al. 1984). The question then arises why M. acetivorans evolved a pathway for utilization of CO independent of H2. One possibility is that, in marine environments, sulfate-reducing microbes outcompete methanogens for H2 (Zinder 1993), presenting the possibility that if H2 were an intermediate it could be lost to sulfate reducers. Another possibility is that Methanosarcina species are at a disadvantage utilizing H2 in the marine environment where the concentrations are kept low by sulfate-reducers and, therefore, have not evolved hydrogenases. Indeed, it is noted that Methanosarcina species have considerably higher threshold concentrations for H2 than do obligate CO2-reducing species (Thauer et al. 2008).

The formation of methanethiol and dimethylsulfide during growth of M. acetivorans on CO was recently reported (Moran et al. 2008). The authors speculate that methyl-groups generated in the CO-dependent reduction of CO2 are transferred to sulfide present in the growth medium and the process could be coupled to energy conservation. However, the rate of dimethylsulfide formation from CO is only 1–2% of that of CH4 formation suggesting the process is not of major consequence in the energy yielding metabolism during growth on CO (Oelgeschlager and Rother 2009).

CO dehydrogenase/Acetyl-COA synthase

Conversion of acetate to CH4

The five-subunit CdhA-E complex is central to pathways for conversion of acetate to methane (Kohler and Zehnder 1984; Krzycki and Zeikus 1984; Nelson and Ferry 1984; Krzycki et al. 1985; Bott et al. 1986; Terlesky et al. 1986; Bott and Thauer 1987; Zinder and Anguish 1992; Gokhale et al. 1993; Kemner and Zeikus 1994) as illustrated in Fig. 5 for M. acetivorans (Li et al. 2006). The complex functions in the pathway to cleave the C-C and C-S bonds of acetyl-CoA yielding a carbonyl group that is oxidized to CO2 and a methyl group that is transferred to THSPt (Terlesky et al. 1987; Fischer and Thauer 1989; Abbanat and Ferry 1990; Raybuck et al. 1991; Grahame 1991, 1993; Grahame and Demoll 1995; Grahame et al. 1996; Bhaskar et al. 1998). In subsequent steps of the pathway, electrons derived from the oxidation of the carbonyl group are transferred to the methyl group producing CH4. The complex also catalyzes the synthesis of acetyl-CoA from a methyl donor, CO and CoA-SH (Abbanat and Ferry 1990; Raybuck et al. 1991). Although a two-subunit CO dehydrogenase has been purified and characterized from an acetate-utilizing species from the genus Methanosaeta (formerly Methanothrix) (Boone and Kamagata 1998) that catalyzes the exchange of CO with the carbonyl group of acetyl-CoA (Jetten et al. 1989, 1991a, b; Eggen et al. 1991), the majority of mechanistic investigations have been with the five-subunit CdhA-E complexes from the acetate-utilizing species Methanosarcina thermophila and M. barkeri described here.

The subunits of the CdhABCDE complex from Methanosarcina species are correspondingly designated αεβγδ and encoded in operons arranged in the order cdhABCDE (Maupin-Furlow and Ferry 1996a, b; Grahame et al. 2005). Use of a plasmid-mediated lacZ fusion reporter system has revealed that the operon encoding the complex of M. thermophila (Grahame et al. 2005) is 54-fold down-regulated in M. acetivorans grown on methanol compared to acetate, consistent with a role for the complex in the pathway for utilization of acetate (Apolinario et al. 2005). The results confirm an earlier report on the regulation of cdhA in M. thermophila examined by northern blotting (Sowers et al. 1993). Unlike the genome of M. thermophila that harbors only one operon encoding CdhA-E (Grahame et al. 2005), the genomes of M. acetivorans (Galagan et al. 2002) and Methanosarcina mazei (Deppenmeier et al. 2002) contain duplicate cdh operons with greater than 95% identity, raising the question as to whether both are transcribed during growth on acetate. A proteomic analysis of M. acetivorans indicates that one complex is expressed at least 16-fold over the other (Li et al. 2006, 2007), consistent with the predominance of a single Cdh complex purified from acetate-grown M. mazei strain Go1 (formerly Methanosarcina frisia) (Maestrojuan et al. 1992), although the organism encodes duplicate cdh operons with high identity (Eggen et al. 1996). However, in apparent contrast to this result, global transcriptional profiling of M. mazei Go1 suggests both cdh operons are transcribed at approximately equal levels (Hovey et al. 2005).

The complex from Methanosarcina species is resolvable into three components (Abbanat and Ferry 1991; Grahame and Demoll 1996; Kocsis et al. 1999). The CdhAE component contains the α and ε subunits, the CdhDE component contains the γ and δ subunits, and the CdhC component contains the β subunit. The CdhAE component has CO dehydrogenase activity with ferredoxin as the electron acceptor (Terlesky and Ferry 1988a, b; Fischer and Thauer 1990). The crystal structure (Gong et al. 2008) of the M. barkeri CdhAE (Fig. 6) shows a α2ε2 configuration with the α subunit harboring a Ni-Fe-S C cluster and four Fe4S4 clusters (B, D, E, and F in Fig. 6) consistent with earlier EPR spectroscopic investigations (Krzycki et al. 1989). The C, B, and D clusters are positioned similarly in the crystal structure of the homolog from Moorella thermoacetica (Ragsdale 2007), an acetate-producing species of the Bacteria domain. However, the E and F clusters are unique to CdhAE and proposed to function in electron transport from the active site C cluster to ferredoxin. The C cluster (Fig. 7) resembles the M. thermoacetica structure comprised of a pseudocubane NiFe3S4 cluster bridged to an exogeneous iron atom. Additional electron density provides support for coupling between CO bound to the nickel and H2O/OH- bound to the exogenous iron in the critical C = O bond-forming step leading to CO2 (Fig. 7). The structure also identifies a gas channel extending from the C cluster to the surface of the protein in a direction presumed to interact with the CdhC component. Structural and sequence alignments indicate that the ε-subunit is a member of the DHS-like NAD/FAD-binding domain clan. Indeed, the structure reveals a cavity able to accommodate an FAD or NAD cofactor located between the interface of the α- and ε-subunits and near the D Fe4-S4 cluster suggesting a potential role in electron transfer. The authors of the structure note that FAD is an electron acceptor for the α2ε2 component (Grahame and Stadtman 1987) suggesting a potential role for the ε-subunit in FAD-mediated CO oxidation during growth on CO.

The Methanosarcina barkeri α2ε2 CdhAE component.a Side view shown as ribbons with the α-subunits colored in cyan and green and the ε-subunits in tan and orange. Metal cluster atoms are shown as spheres, with iron atoms in purple, nickel atoms in blue, and the remaining atoms in CPK. b Side view of the metal clusters. By permission (Gong et al. 2008)

The CdhDE component transfers the methyl group of acetyl-CoA to THSPt and contains an iron-sulfur center and corrinoid cofactors that transfer the methyl group during catalysis (Grahame 1991, 1993; Jablonski et al. 1993; Maupin-Furlow and Ferry 1996a). Analyses of the CdhD and CdhE subunits overproduced independently in E. coli indicates that the iron-sulfur center is located in the CdhE subunit and that both subunits bind a corrinoid cofactor. Which of the two subunits interact with THSPt has not been determined. A structure has not been reported for either subunit; however, EPR analyses of the intact CdhDE component (Jablonski et al. 1993) indicate that the corrinoids are maintained in the base-off state with a E ′o of -486 mV for the Co2+/1+ couple that facilitates reduction of Co2+ by approximately 12 kcal/mol relative to base-on cobamides. Reduction to the Co1+ redox state is a requirement for methylation of corrinoid cofactors. The EPR analysis also identified a [4Fe-4S]2+/1+ cluster with an E 'o of -502 mV, approximately isopotential with the Co2+/1+ couple suggesting the cluster is likely involved in reducing Co2+.

The CdhC component contains an A cluster that is the proposed site of acetyl-CoA cleavage or synthesis (Grahame and Demoll 1996; Murakami and Ragsdale 2000; Gencic and Grahame 2003; Funk et al. 2004). Although a structure is not available, a variety of spectroscopic studies suggest the A cluster is comprised of an Fe4S4 center bridged to a binuclear Ni-Ni site (Gu et al. 2003; Funk et al. 2004) similar in structure (Fig. 8) to that proposed for the homolog from M. thermoacetica (Ragsdale 2007). In addition to CO oxidation, the CdhAE component is required for acetyl-CoA cleavage or synthesis (Murakami and Ragsdale 2000). The authors propose a mechanism for acetyl-CoA synthesis or cleavage involving an intramolecular electron transfer reaction between the C cluster in the CdhAE component and cluster A in the CdhC component for each catalytic cycle thereby maintaining Ni in cluster A in the catalytically active Ni(I) redox state. The redox dependence of acetyl-CoA synthesis by the CdhC component shows one-electron Nernst behavior and that two electrons are required for reductive activation of the active site Ni in the process of forming the enzyme-acetyl intermediate (Gencic and Grahame 2008).

Structure of the A cluster from Moorella thermoacetica. By permission (Ragsdale 2007)

Autotrophy

Many methanogens grow autotrophically with CO2 as sole source of carbon (Ferry and Kastead 2007). For example, M. thermoautotrophicum is able to grow with H2 and CO2 in a simple mineral salts medium (Zeikus and Wolfe 1972; Schonheit et al. 1980) synthesizing acetyl-CoA (Stupperich and Fuchs 1983; Stupperich et al. 1983; Ruhlemann et al. 1985), the starting point for synthesis of all cellular components (Fuchs and Stupperich 1980). Acetyl-CoA is synthesized via methyl-tetrahydromethanopterin (methyl-THMPt) providing the methyl group and CO the carboxyl group (Lange and Fuchs 1985, 1987). The CO is generated from CO2 and H2 in an energy-dependent reaction (Conrad and Thauer 1983; Eikmanns et al. 1985) and methyl-THMPt via steps in the pathway for CO2 reduction to methane (Lange and Fuchs 1987) similar to that shown in Fig. 3 (reactions 2–8). The THMPt in M. thermoautotrophicum is an analog of THSPt found in Methanosarcina species. Autotrophic methanogens such as M. thermoautotrophicum have CO dehydrogenase activity whereas heterotrophic methanogens lack CO dehydrogenase and require acetate as the carbon source that is converted to acetyl-CoA (Bott et al. 1985). Indeed, the genome of M. thermoautotrophicum contains a gene cluster encoding subunits with high identity to subunits of the CdhA-E complex of acetate-utilizing Methanosarcina species (The Comprehensive Microbial Resource. J. Craig Venter Institute, http://cmr.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi). Furthermore, a CO dehydrogenase was purified from the autotrophic methanogen Methanococcus vannielii that contains nickel and is composed of subunits with molecular weights similar to the CdhAE component (DeMoll et al. 1987). These results are consistent with synthesis of acetyl-CoA in autotrophic methanogens catalyzed by a CO dehydrogenase with properties similar to the CdhA-E complex of acetate-utilizing species.

Evolution

It is proposed that Earth’s atmosphere at the time of the origin of life contained significant amounts of CO (Holland 1984; Kasting 1990; Kharecha et al. 2005) and that the CdhA-E complex of methanogens and homologs in the Bacteria domain evolved early during the origin and evolution of primitive life forms (Lindahl and Chang 2001). In the chemoautotrophic origin of life (Russell et al. 1988; Wachtershauser 1988; Russell and Hall 1997), the primary pre-biotic initiation reaction for carbon fixation was the surface-catalyzed synthesis of an acetate thioester from CO and H2S driven by a geochemical energy source. A prominent feature of the chemoautotrophic theory is the evolution of biological CO2 fixation pathways of which one is a primitive form of the extant Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (Wachtershauser 1997; Pereto et al. 1999; Martin and Russell 2003; Russell and Martin 2004) in which 2CO2 molecules are reduced to acetyl-CoA implying early evolution of primitive forms of enzymes with catalytic capabilities of the CdhA-E complex of methanogens and homologs in the Bacteria domain. A role for a primitive form of CdhC has been proposed in a modification of the chemoautotrophic theory (Ferry and House 2006). In the modified theory, the primitive CdhC catalyzes C-S bond formation (reaction A in Fig. 9a) regenerating the CH3COSR thioester from acetate and HS-R that is the energy source in the first energy-yielding metabolic cycle. Reaction A in Fig. 9a is driven by the conversion of FeS and H2S to pyrite and H2 a previously proposed energy source in the chemoautotrophic theory (Wachtershauser 1988). The theory also proposes roles for primitive forms of phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase (reactions B and C, Fig. 9a). In contrast to biosynthetic pathways, the cycle is proposed to have been the major force that powered and directed the early evolution of life that included acetogens and methanogens (Ferry and House 2006). The next proposed step in evolution of extant CdhA-E and its homologs in the Bacteria domain (Ferry and House 2006) is evolution of CO dehydrogenase activity (reaction A, Fig. 9b) and C-C bond formation (reaction B, Fig. 9b) that allowed the synthesis of thioesters from CO and a methyl group derived from co-evolution of enzymes leading to the reduction of CO2 to the methyl level that is the extant Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (Fig. 9b). Thus, it is proposed that the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway first evolved as an energy-yielding pathway that was adapted for biosynthesis of cell carbon, and evolution of the first autotroph, once the pre-biotic organic soup was exhausted for incorporation into cell material (Ferry and House 2006). It is further proposed that the pathway shown in Fig. 9b was the foundation for evolution of methanogenic pathways.

The proposed cyclic energy-conserving pathway that functioned in the primitive (a) and chemoautotrophic cell independent of surface-catalyzed reactions (b) (Ferry and House 2006). The stippled areas represent the lipid membranes. Pi represents inorganic phosphate. a Solid lines indicate the cyclic pathway (steps A–C). The broken arrow indicates the priming reaction that is not part of the cyclic pathway. b THMPT Tetrahydromethanopterin. By permission (Ferry and House 2006)

Conclusions

Methanogens play an essential role in the global carbon cycle by serving as terminal organisms in anaerobic microbial food chains that convert complex organic matter to CH4 and CO2. They utilize simple molecules for growth that include acetate and several one-carbon compounds. Although first reported in 1931, comparatively little is known today of the ecology, physiology, and biochemistry of CO utilization by methanogens. Only a few species are reported to metabolize CO, and it is not yet known unequivocally if CO is a viable energy source for methanogens in diverse environments. However, recent investigations of M. acetivorans suggest this methanogen utilizes CO as a growth substrate in nature converting CO, abundant in the native habitat, to CH4 and acetate via an unusual pathway. CO is also an important intermediate during growth of methanogens on acetate and assimilation of CO2 for cell carbon. Clearly, more research is warranted to determine the extent of CO utilization by methanogens in native environments.

References

Abbanat DR, Ferry JG (1990) Synthesis of acetyl-CoA by the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase complex from acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol 172:7145–7150

Abbanat DR, Ferry JG (1991) Resolution of component proteins in an enzyme complex from Methanosarcina thermophila catalyzing the synthesis or cleavage of acetyl-CoA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:3272–3276

Abbott IA, Hollenberg GJ (1976) Marine algae of California. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Apolinario EE, Jackson KM, Sowers KR (2005) Development of a plasmid-mediated reporter system for in vivo monitoring of gene expression in the archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4914–4918

Bhaskar B, DeMoll E, Grahame DA (1998) Redox-dependent acetyl transfer partial reaction of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex: kinetics and mechanism. Biochemistry 37:14491–14499

Boone DR, Kamagata Y (1998) Rejection of the species Methanothrix soehngenii VP and the genus Methanothrix VP as nomina confusa, and transfer of Methanothrix thermophila VP to the genus Methanosaeta VP as Methanosaeta thermophila comb. nov. Request for an opinion. Int J Syst Bacteriol 48:1079–1080

Bott M, Thauer RK (1987) Proton-motive-force-driven formation of CO from CO2 and H2 in methanogenic bacteria. Eur J Biochem 168:407–412

Bott MH, Eikmanns B, Thauer RK (1985) Defective formation and/or utilization of carbon monoxide in H2/CO2 fermenting methanogens dependent on acetate as carbon source. Arch Microbiol 143:266–269

Bott M, Eikmanns B, Thauer RK (1986) Coupling of carbon monoxide oxidation to CO 2 and H 2 with the phosphorylation of ADP in acetate-grown Methanosarcina barkeri. Eur J Biochem 159:393–398

Bryant MP, Boone DR (1987) Emended description of strain MST (DSM 800 T), the type strain of Methanosarcina barkeri. Int J Syst Bacteriol 37:169–170

Conrad R, Seiler W (1980) Role of microorganisms in the consumption and production of atmospheric carbon monoxide by soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 40:437–445

Conrad R, Thauer RK (1983) Carbon monoxide production by Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. FEMS Microbiol Lett 20:229–232

Daniels L, Fuchs G, Thauer RK, Zeikus JG (1977) Carbon monoxide oxidation by methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 132:118–126

DeMoll E, Grahame DA, Harnly JM, Tsai L, Stadtman TC (1987) Purification and properties of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Methanococcus vannielii. J Bacteriol 169:3916–3920

Deppenmeier U, Johann A, Hartsch T, Merkl R, Schmitz RA, Martinez-Arias R et al (2002) The genome of Methanosarcina mazei: evidence for lateral gene transfer between Bacteria and Archaea. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 4:453–461

Eggen RIL, Geerling ACM, Jetten MSM, Devos WM (1991) Cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of the genes for carbon monoxide dehydrogenase of Methanothrix soehngenii. J Biol Chem 266:6883–6887

Eggen RIL, Vankranenburg R, Vriesema AJM, Geerling ACM, Verhagen MFJM, Hagen WR, Devos WM (1996) Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Methanosarcina frisia Go1. Characterization of the enzyme and the regulated expression of two operon-like cdh gene clusters. J Biol Chem 271:14256–14263

Eikmanns B, Fuchs G, Thauer RK (1985) Formation of carbon monoxide from CO2 and H2 by Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Eur J Biochem 146:149–154

Ferry JG (2008) Acetate-based methane production. In: Wall JD, Harwood CS, Demain A (eds) Bioenergy. ASM Press, Washington, D.C., pp 155–170

Ferry JG, House CH (2006) The stepwise evolution of early life driven by energy conservation. Mol Biol Evol 23:1286–1292

Ferry JG, Kastead KA (2007) Methanogenesis. In: Cavicchioli R (ed) Archaea: molecular cell biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C., pp 288–314

Ferry JG, Lessner DJ (2008). Methanogenesis in Marine Sediments. In: Wiegel J, Maier R, Adams MWW (eds) Incredible anaerobes: from physiology to genomics to fuels. Ann NY Acad Sci, pp 147–157

Fischer R, Thauer RK (1989) Methyltetrahydromethanopterin as an intermediate in methanogenesis from acetate in Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol 151:459–465

Fischer R, Thauer RK (1990) Ferredoxin-dependent methane formation from acetate in cell extracts of Methanosarcina barkeri (strain MS). FEBS Lett 269:368–372

Fischer F, Lieske R, Winzer K (1931) Biologische gasreaktionen. I. Mitteilung: die umsetzung des kohlenoxyds. Biochem Z 236:247–267

Fischer F, Lieske R, Winzer K (1932) Uber die bildung von essigsaure bei der biologischen umsetzung von kohlenoxyd und kohlensaure mit wasserstoff zu methan. Biochem Z 245:2–12

Fuchs G, Stupperich E (1980) Acetyl CoA, a central intermediate of autotrophic CO2 fixation in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Arch Microbiol 127:267–272

Funk T, Gu WW, Friedrich S, Wang HX, Gencic S, Grahame DA, Cramer SP (2004) Chemically distinct Ni sites in the A-cluster in subunit beta of the Acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex from Methanosarcina thermophila: Ni L-edge absorption and x-ray magnetic circular dichroism analyses. J Am Chem Soc 126:88–95

Galagan JE, Nusbaum C, Roy A, Endrizzi MG, Macdonald P, FitzHugh W et al (2002) The genome of M. acetivorans reveals extensive metabolic and physiological diversity. Genome Res 12:532–542

Gencic S, Grahame DA (2003) Nickel in subunit b of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase multienzyme complex in methanogens. J Biol Chem 278:6101–6110

Gencic S, Grahame DA (2008) Two separate one-electron steps in the reductive activation of the A cluster in subunit beta of the ACDS complex in Methanosarcina thermophila. Biochemistry 47:5544–5455

Gokhale JU, Aldrich HC, Bhatnagar L, Zeikus JG (1993) Localization of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase in acetate- adapted Methanosarcina barkeri. Can J Microbiol 39:223–226

Gong W, Hao B, Wei Z, Ferguson DJ Jr, Tallant T, Krzycki JA, Chan MK (2008) Structure of the a2e2 Ni-dependent CO dehydrogenase component of the Methanosarcina barkeri acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:9558–9563

Gottschalk G, Thauer RK (2001) The Na+ translocating methyltransferase complex from methanogenic archaea. Biochim Biophys Acta 1505:28–36

Grahame DA (1991) Catalysis of acetyl-CoA cleavage and tetrahydrosarcinapterin methylation by a carbon monoxide dehydrogenase-corrinoid enzyme complex. J Biol Chem 266:22227–22233

Grahame DA (1993) Substrate and cofactor reactivity of a carbon monoxide dehydrogenase corrinoid enzyme complex. Stepwise reduction of iron sulfur and corrinoid centers, the corrinoid Co2+/1+ redox midpoint potential, and overall synthesis of acetyl-CoA. Biochemistry 32:10786–10793

Grahame DA, Stadtman TC (1987) Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Methanosarcina barkeri. Disaggregation, purification, and physicochemical properties of the enzyme. J Biol Chem 262:3706–3712

Grahame DA, Demoll E (1995) Substrate and accessory protein requirements and thermodynamics of acetyl-CoA synthesis and cleavage in Methanosarcina barkeri. Biochemistry 34:4617–4624

Grahame DA, Demoll E (1996) Partial reactions catalyzed by protein components of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase synthase enzyme complex from Methanosarcina barkeri. J Biol Chem 271:8352–8358

Grahame DA, Khangulov S, Demoll E (1996) Reactivity of a paramagnetic enzyme-CO adduct in acetyl-CoA synthesis and cleavage. Biochemistry 35:593–600

Grahame DA, Gencic S, Demoll E (2005) A single operon-encoded form of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase multienzyme complex responsible for synthesis and cleavage of acetyl-CoA in Methanosarcina thermophila. Arch Microbiol 184:1–9

Gu WW, Gencic S, Cramer SP, Grahame DA (2003) The A-cluster in subunit beta of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex from Methanosarcina thermophila: Ni and Fe K-Edge XANES and EXAFS analyses. J Am Chem Soc 125:15343–15351

Holland HD (1984) Chemical evolution of the atmosphere and oceans. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, pp 29–59

Hovey R, Lentes S, Ehrenreich A, Salmon K, Saba K, Gottschalk G et al (2005) DNA microarray analysis of Methanosarcina mazei Go1 reveals adaptation to different methanogenic substrates. Mol Genet Genomics 273:225–239

Jablonski PE, Lu WP, Ragsdale SW, Ferry JG (1993) Characterization of the metal centers of the corrinoid/iron- sulfur component of the CO dehydrogenase enzyme complex from Methanosarcina thermophila by EPR spectroscopy and spectroelectrochemistry. J Biol Chem 268:325–329

Jetten MSM, Stams AJM, Zehnder AJB (1989) Purification and characterization of an oxygen-stable carbon monoxide dehydrogenase of Methanothrix soehngenii. FEBS Lett 181:437–441

Jetten MSM, Pierik AJ, Hagen WR (1991a) EPR characterization of a high-spin system in carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Methanothrix soehngenii. Eur J Biochem 202:1291–1297

Jetten MSM, Hagen WR, Pierik AJ, Stams AJM, Zehnder AJB (1991b) Paramagnetic centers and acetyl-coenzyme A/CO exchange activity of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Methanothrix soehngenii. Eur J Biochem 195:385–391

Kasting JF (1990) Bolide impacts and the oxidation state of carbon in the Earth's early atmosphere. Orig Life Evol Biosph 20:199–231

Kemner JM, Zeikus G (1994) Regulation and function of ferredoxin-linked versus cytochrome b-linked hydrogenase in electron transfer and energy metabolism of Methanosarcina barkeri MS. Arch Microbiol 162:26–32

Kharecha P, Kasting J, Siefert J (2005) A coupled atmosphere-ecosystem model of the early Archean Earth. Geobiology 3:53–76

Kluyver AJ, Schnellen CGTP (1947) On the fermentation of carbon monoxide by pure cultures of methane bacteria. Arch Biochem 14:57–70

Kocsis E, Kessel M, DeMoll E, Grahame DA (1999) Structure of the Ni/Fe-S protein subcomponent of the acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex from Methanosarcina thermophila at 26-A resolution. J Struct Biol 128:165–174

Kohler H-PE, Zehnder AJB (1984) Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase and acetate thiokinase in Methanothrix soehngenii. FEMS Microbiol Lett 21:287–292

Krzycki JA, Zeikus JG (1984) Characterization and purification of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Methanosarcina barkeri. J Bacteriol 158:231–237

Krzycki JA, Lehman LJ, Zeikus JG (1985) Acetate catabolism by Methanosarcina barkeri: evidence for involvement of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, methyl coenzyme M, and methylreductase. J Bacteriol 163:1000–1006

Krzycki JA, Mortenson LE, Prince RC (1989) Paramagnetic centers of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from aceticlastic Methanosarcina barkeri. J Biol Chem 264:7217–7221

Lange S, Fuchs G (1985) Tetrahydromethanopterin, a coenzyme involved in autotrophic acetyl coenzyme A synthesis from 2 CO2 in Methanobacterium. FEBS Lett 181:303–307

Lange S, Fuchs G (1987) Autotrophic synthesis of activated acetic acid from CO2 in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Synthesis from tetrahydromethanopterin-bound C1 units and carbon monoxide. Eur J Biochem 163:147–154

Lessner DJ, Li L, Li Q, Rejtar T, Andreev VP, Reichlen M et al (2006) An unconventional pathway for reduction of CO2 to methane in CO-grown Methanosarcina acetivorans revealed by proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:17921–17926

Li Q, Li L, Rejtar T, Lessner DJ, Karger BL, Ferry JG (2006) Electron transport in the pathway of acetate conversion to methane in the marine archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans. J Bacteriol 188:702–710

Li L, Li Q, Rohlin L, Kim U, Salmon K, Rejtar T et al (2007) Quantitative proteomic and microarray analysis of the archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans grown with acetate versus methanol. J Proteome Res 6:759–771

Lindahl PA, Chang B (2001) The evolution of acetyl-CoA synthase. Orig Life Evol Biosph 31:403–434

Liu Y, Whitman WB (2008) Metabolic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of the methanogenic archaea. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125:171–189

Maestrojuan GM, Boone JE, Mah RA, Menaia JAGF, Sachs MS, Boone DR (1992) Taxonomy and halotolerance of mesophilic methanosarcina strains, assignment of strains to species, and synonymy of Methanosarcina mazei and Methanosarcina frisia. Int J Syst Bacteriol 42:561–567

Martin W, Russell MJ (2003) On the origins of cells: a hypothesis for the evolutionary transitions from abiotic geochemistry to chemoautotrophic prokaryotes, and from prokaryotes to nucleated cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 358:59–85

Maupin-Furlow J, Ferry JG (1996a) Characterization of the cdhD and cdhE genes encoding subunits of the corrinoid iron-sulfur enzyme of the CO dehydrogenase complex from Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol 178:340–346

Maupin-Furlow JA, Ferry JG (1996b) Analysis of the CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-coenzyme A synthase operon of Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol 178:6849–6856

Moran JJ, House CH, Vrentas JM, Freeman KH (2008) Methyl sulfide production by a novel carbon monoxide metabolism in Methanosarcina acetivorans. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:540–542

Murakami E, Ragsdale SW (2000) Evidence for intersubunit communication during acetyl-CoA cleavage by the multienzyme CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase complex from Methanosarcina thermophila. Evidence that the beta subunit catalyzes C-C and C-S bond cleavage. J Biol Chem 275:4699–4707

Nelson MJK, Ferry JG (1984) Carbon monoxide-dependent methyl coenzyme M methylreductase in acetotrophic Methanosarcina spp. J Bacteriol 160:526–532

O'Brien JM, Wolkin RH, Moench TT, Morgan JB, Zeikus JG (1984) Association of hydrogen metabolism with unitrophic or mixotrophic growth of Methanosarcina barkeri on carbon monoxide. J Bacteriol 158:373–375

Oelgeschlager E, Rother M (2008) Carbon monoxide-dependent energy metabolism in anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Arch Microbiol 190:257–269

Oelgeschlager E, Rother M (2009) Influence of carbon monoxide on metabolite formation in Methanosarcina acetivorans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 292:254–260

Pereto JG, Velasco AM, Becerra A, Lazcano A (1999) Comparative biochemistry of CO2 fixation and the evolution of autotrophy. Int Microbiol 2:3–10

Ragsdale SW (2007) Nickel and the carbon cycle. J Inorg Biochem 101:1657–1666

Raybuck SA, Ramer SE, Abbanat DR, Peters JW, Orme-Johnson WH, Ferry JG, Walsh CT (1991) Demonstration of carbon-carbon bond cleavage of acetyl coenzyme A by using isotopic exchange catalyzed by the CO dehydrogenase complex from acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol 173:929–932

Rother M, Metcalf WW (2004) Anaerobic growth of Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A on carbon monoxide: An unusual way of life for a methanogenic archaeon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:16929–16934

Rother M, Oelgeschlager E, Metcalf WM (2007) Genetic and proteomic analyses of CO utilization by Methanosarcina acetivorans. Arch Microbiol 188:463–472

Ruhlemann M, Ziegler K, Stupperich E, Fuchs G (1985) Detection of acetyl coenzyme A as an early CO2 assimilation intermediate in Methanobacterium. Arch Microbiol 141:399–406

Russell MJ, Hall AJ (1997) The emergence of life from iron monosulphide bubbles at a submarine hydrothermal redox and pH front. J Geol Soc Lond 154:377–402

Russell MJ, Martin W (2004) The rocky roots of the acetyl-CoA pathway. Trends Biochem Sci 29:358–363

Russell MJ, Hall AJ, Cairns-Smith AG, Braterman PS (1988) Submarine hot springs and the origin of life. Nature 336:117

Schonheit P, Moll J, Thauer RK (1980) Growth parameters (K s, mmax, Y s) of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Arch Microbiol 127:59–65

Sowers KR, Baron SF, Ferry JG (1984) Methanosarcina acetivorans sp. nov., an acetotrophic methane-producing bacterium isolated from marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 47:971–978

Sowers KR, Thai TT, Gunsalus RP (1993) Transcriptional regulation of the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase gene (cdhA) in Methanosarcina thermophila. J Biol Chem 268:23172–23178

Spanheimer R, Muller V (2008) The molecular basis of salt adaptation in Methanosarcina mazei Go1. Arch Microbiol 189:431–439

Stephenson M, Stickland LH (1933) Hydrogenase. The bacterial formation of methane by the reduction of one-carbon compounds by molecular hydrogen. Biochem J 27:1517–1527

Stojanowic A, Hedderich R (2004) CO2 reduction to the level of formylmethanofuran in Methanosarcina barkeri is non-energy driven when CO is the electron donor. FEMS Microbiol Lett 235:163–167

Stupperich E, Fuchs G (1983) Autotrophic acetyl coenzyme A synthesis in vitro from two CO2 in Methanobacterium. FEBS Lett 156:345–348

Stupperich E, Hammel KE, Fuchs G, Thauer RK (1983) Carbon monoxide fixation into the carboxyl group of acetyl coenzyme A during autotrophic growth of Methanobacterium. FEBS Lett 152:21–23

Terlesky KC, Ferry JG (1988a) Ferredoxin requirement for electron transport from the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase complex to a membrane-bound hydrogenase in acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Biol Chem 263:4075–4079

Terlesky KC, Ferry JG (1988b) Purification and characterization of a ferredoxin from acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Biol Chem 263:4080–4082

Terlesky KC, Nelson MJK, Ferry JG (1986) Isolation of an enzyme complex with carbon monoxide dehydrogenase activity containing a corrinoid and nickel from acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol 168:1053–1058

Terlesky KC, Barber MJ, Aceti DJ, Ferry JG (1987) EPR properties of the Ni-Fe-C center in an enzyme complex with carbon monoxide dehydrogenase activity from acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. Evidence that acetyl-CoA is a physiological substrate. J Biol Chem 262:15392–15395

Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R (2008) Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:579–591

Wachtershauser G (1988) Pyrite formation, the first energy source for life: a hypothesis. Syst Appl Microbiol 10:207–210

Wachtershauser G (1997) The origin of life and its methodological challenge. J Theor Biol 187:483–494

Zeikus JG, Wolfe RS (1972) Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum sp. n., an anaerobic, autotrophic, extreme thermophile. J Bacteriol 109:707–713

Zinder S (1993) Physiological ecology of methanogens. In: Ferry JG (ed) Methanogenesis. Chapman and Hall, New York, NY, pp 128–206

Zinder SH, Anguish T (1992) Carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and formate metabolism during methanogenesis from acetate by thermophilic cultures of Methanosarcina and Methanothrix strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 58:3323–3329

Acknowledgements

Research in the laboratory of J.G.F has been supported by the NIH, DOE, NSF, and NASA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferry, J.G. CO in methanogenesis. Ann Microbiol 60, 1–12 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-009-0008-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-009-0008-5