Abstract

Between 2000 and 2011, over 170 second-year medical students participated in a Determinants of Community Health (DOCH 2) project at Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH). Students undertook community-based research projects at the hospital or with PMH community partners involving activities such as producing a literature review, writing a research proposal, obtaining ethics approval, carrying out data collection and analysis, presenting their data to classmates and supervisors, and production of a final report. An electronic survey consisting of both quantitative and qualitative questions was developed to evaluate the PMH-DOCH 2 program and was distributed to 144 past students with known email addresses. Fifty-eight students responded, a response rate of 40.3 %. Data analysis indicates that an increase in oncology knowledge, awareness of the impact of determinants of health on patients, and knowledge of research procedures increased participants’ satisfaction and ability to conduct research following DOCH 2. Furthermore, the PMH-DOCH 2 program enhanced the development of CanMEDS competencies through career exploration and patient interaction as well as through shadowing physicians and other allied health professionals. In addition, some students felt their PMH-DOCH 2 projects played a beneficial role during their residency matching process. The PMH-DOCH 2 research program appeared to provide a positive experience for most participants and opportunities for medical students’ professional growth and development outside the confines of traditional lecture-based courses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Canadian medical education is guided by the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework [1]. Although the medical expert role is strongly emphasized, medical school curricula increasingly promote the scholar, health advocate, communicator, collaborator, professional, and manager roles. Of particular importance is the role of research and evidence-based medicine in patient care [2, 3]; physicians must understand the evidence behind clinical decisions and interpret as well as participate in studies and resource creation to address patients’ needs [4]. Without research skills, delayed or stagnant problem solving may occur. Ideally, early research exposure leads to a greater knowledge of conducting and using research in future practice [5]. Ultimately, research skills training enables medical students to continually assess needs, evaluate interventions, and develop programs addressing patient care issues [6].

Determinants of Community Health

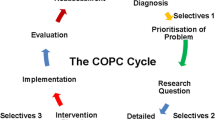

The University of Toronto’s second-year Determinants of Community Health (DOCH 2) course addresses community health-care needs by enhancing medical student’s awareness of factors and resources that promote health and enhance clinical practice [7]. Preclinical students learn research practices and interact with patients via community-based research projects in which they participate in project design, ethics approval, data analysis and synthesis, formal project presentation, and write-up. Students may self-initiate their own research projects with a supervisor or choose from the course catalogue.

Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (Princess Margaret Hospital)

The Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH) in Toronto, Ontario, is a world leader in cancer care, research, and education. The patient education program provides comprehensive individualized education to patients and loved ones, while promoting collaborative interdisciplinary patient and staff education [8, 9]. A strong research program ensures evidence-based best practice [10].

DOCH 2 at PMH

Between 2000 and 2011, over 170 DOCH 2 students completed patient education research at PMH, including needs assessment [11–14], resource development [15], resource evaluation [16–18], and program evaluation [19, 20] projects. In the process, students were exposed to clinical, research, and academic activities in oncology as well as patient contact and mentorship by diverse allied health professionals [21]. This study (1) evaluated the program impact and value on knowledge acquisition, (2) determined factors enhancing student satisfaction and learning, and (3) provided recommendations for program improvement.

Methodology

Ethics approval was received from both PMH/University Health Network and the University of Toronto. From 2000 to 2010, over 170 students completed a PMH-DOCH 2 project. A request to participate in an on-line questionnaire (www.surveymonkey.com) was emailed to each student. Two reminders were sent during a 5-week data collection period. Implied consent was obtained from all participants.

Survey Development

Survey questions were developed following a literature review and using Kirkpatrick’s educational outcome model [22]. Survey drafts were reviewed by course directors, clinicians, educators, and PMH research staff. The survey was validated with a small sample of DOCH 2 students not placed at PMH. The final semi-structured survey questions investigated demographics, project outcomes, research capacity and learning, and project impact on residency, career choice, and oncology awareness and interest.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS 19 [23]. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and independent t tests were used as appropriate. Post hoc Bonferroni tests were run following significant ANOVA and regression analysis on selecting variables to determine if correlations existed (p < 0.05, significance). Two investigators independently analyzed qualitative data using descriptive thematic analysis of trends in student perceptions, attitudes, and experiences. Patterns were then jointly identified. Jointly coded data underwent increasingly finer categorization until all trends and variations were accounted for and cross-referenced.

Results

Of 154 known email addresses of 170 graduates, ten were invalid, yielding 144 contacts. The 58 respondents (40.2 % response rate) included third- and fourth-year medical students, residents, and licensed physicians with more numerous responses from recent graduates (Table 1). The majority (85 %) selected course provided rather than self-initiated projects (10 %). Most respondents completed needs/barrier assessments (39 %), followed by program and resource evaluation (24 and 21 %), and resource development (16 %) projects, a typical course project distribution. Nearly all had previous research experience (54 versus 4), especially in basic sciences (28 versus 17 in clinical/epidemiological research; 9 in qualitative research).

No significant satisfaction difference existed between males (3.52 ± 0.75) and females (3.61 ± 1.29, p = 0.75) or between those producing academic outcomes (e.g., presentation, publication, abstract) (3.67 ± 1.16) and none (3.33 ± 0.976, p = 0.29). A significant difference existed between those with self-initiated projects (4.67 ± 0.512) and those choosing course list projects (3.42 ± 1.10, p = 0.001). One student recommended, “Self-initiate to set yourself up in a worthwhile project. These are a lot of work and you get much more out of it if you have a good project that is publishable” (ID 45). Another advised, “Undertake self-initiated project tailored to specialty of interest if you are hoping to use it as part of your CaRMS [Canadian Resident Matching Service] application” (ID 31).

A positive relationship existed between supervisory guidance and satisfaction. “[My supervisor was] always accessible and very amenable to answering questions, providing feedback, etc.” (ID 25). “It was difficult to get in touch with my supervisor, and it felt overwhelming at certain times when trying to attain deadlines. [The hospital program lead], however, was extremely helpful and I was able to complete everything without a problem” (ID 40). Students who met less with their supervisor (2.70 ± 1.42) were significantly less satisfied than those meeting more frequently (3.77 ± 0.96, p = 0.05). They explained, “Supervisor was often absent. Wouldn’t respond to questions or emails. Left me out of the loop quite a bit” (ID 44). “It was difficult to get a hold of the [supervisor] and she would often cancel” (ID 23). Moderate correlations existed between satisfaction and shadowing allied health professionals (r = 0.478, p = 0.001), patient interactions (r = 0.532, p = 0.001), research mentorship and guidance (r = 0.672, p = 0.001), and attending project-related events (r = 0.500, p = 0.002).

Students became more aware of the intradisciplinary nature of oncology patient care:

Great experience overall. Great opportunity to work with other disciplines, and be involved in a more holistic approach to health (rather than just treatment specific)…. Attending some of the programs available for cancer patients was a great experience to meet and speak with patients first hand (ID 40).

I don’t think it matters [for CaRMS] whether anything was publicized, but it was good to show that I worked with members of an interdisciplinary team and that I could appreciate other aspects of medicine other than just diagnosis and treatments (ID 40).

Opinions varied regarding increased research capacity. On the positive side, “It is always good to have some research experience on your CV. The DOCH 2 project offers an opportunity to gain that experience if you haven’t already been able to elsewhere during your training” (ID 8). Others stated, “DOCH 2 was not useful. I already had a research background” (ID 21). “I didn’t feel that the project was of much value or advanced my research knowledge. It was simply a requirement of the course” (ID 60).

Completing the ethics approval process “from start to finish” was beneficial (ID 1) and “a new and useful experience” (ID 20). “Learning the particulars of the process—applications, plans, budgets, research ethics board approval etc.—were all helpful in teaching me about the manner in which research is conducted” (ID 51). However, short project timelines were challenging: “The timeline for the DOCH 2 project meant that there was little actual time to gather data. I felt that the project was more about writing a research proposal and getting through ethics than actually collecting and evaluating data” (ID 28). Another student “found it difficult to incorporate the [course] requirements for the DOCH 2 project with the research question my supervisor wanted to answer” (ID 57). “First time” exposure to qualitative research methods was valuable: “[I learned] how to conduct qualitative research. I had only had experience with quantitative research prior to DOCH 2. I have since used these skills toward my resident PGY2 project” (ID 15). “Doing a qualitative study was an interesting and useful experience and it increased my appreciation of quality research projects” (ID 28). An academic presentation or publication (2.20 ± 0.94) significantly increased perceived research capacity improvement versus no academic output (3.90 ± 1.11, p = 0.03).

Personal Development, Career Exploration, and Choice

Prior interest in oncology often led to project choices at PMH and, therefore, little change in respondent interest in oncology-related fields. However, PMH-DOCH 2 placements provided opportunities for career exploration and had utility during residency interviews (Table 2). The program strength was patient contact, which resulted in an increased understanding of their experiences, more empathy and compassion, and improved ability to support patients (Table 3).

Discussion

The survey response rate was 40.8 % across different training levels (medical student, resident, licensed physician). Interestingly, 93 % of respondents had prior research experience, mostly in the basic sciences. Few had prior exposure to qualitative research. The majority produced a publication or presentation, demonstrating the academic benefits of the program for both students and supervisors.

Opinions varied regarding whether research capacity was enhanced. As expected, participating in a self-directed project, rather than one from the course catalogue, generated higher satisfaction and projects more tailored to students’ own goals and interests. Students are now encouraged to self-initiate projects to maximize satisfaction and personal relevance. More varied catalogue projects are now presented to reduce satisfaction disparities between the two groups (4.67 ± 0.51 versus 3.42 ± 1.10, p = 0.001).

Although many students had prior research experience, the program allowed several to explore new qualitative research methods as well as all stages of the research process, including study design, ethics approval, data collection, and synthesis. Graduates often felt overwhelmed by the heavy course time commitment and recommended more protected research time, strongly emphasizing the importance of course deadlines, commencing DOCH 2 projects in first year and decreasing course requirements. DOCH 2 projects are now being introduced in first year, and the project match occurs earlier in year 2, resulting in more time for familiarization with the placement and project development.

The degree and quality of supervision (i.e., supervisor availability, contact time, and setting clear expectations) impacted satisfaction and research outcomes. Students receiving significant supervisor guidance tended to have more positive experiences. The PMH program coordinator provided additional assistance to students lacking sufficient support. Suggestions for improvement included clearly outlining expectations to both students and project supervisors regarding communication and time commitment, increasing hospital-based support staff and scheduling mandatory meeting times. Prior academic publications or abstracts (i.e., research experience) did not significantly impact enhanced research capacity among these respondents, perhaps due to a general lack of student’s exposure to qualitative research prior to DOCH 2. It may be beneficial in the future to analyze the impact of previous qualitative research experience on satisfaction and research skills development. Unsurprisingly, students who produced an academic publication, abstract, or presentation had higher self-rated research capacity, likely due to the additional mentorship, work, and learning required to create such outputs. PMH-DOCH 2 projects appeared to enhance interest and knowledge of oncology. Some participants were drawn to the program due to prior interest; others were drawn to oncology as a result of their PMH-DOCH 2 experiences (Table 2). Preclinical training does not emphasize oncology patient interaction, and graduates greatly appreciated this element. Arguably, medical students are more likely to pursue careers and specialties that they have been exposed to. This program allows students to explore clinical oncology and interact with patients, while developing diverse skills for future practice. Developing an understanding of the psychosocial impact and multidisciplinary approach necessary for cancer care is difficult to generate outside clinical settings. The PMH-DOCH 2 project also provided some students with evidence for their motivation for particular residencies during interviews and applications. The authors hope that such exposures will ultimately result in more educated oncology referrals and deeper oncology understanding by these future physicians, regardless of their specialty.

Medical knowledge is blossoming, and greater appreciation exists for the value of skills and knowledge beyond the traditional medical expert role. The PMH-DOCH 2 program allowed students to develop nonmedical expert CanMEDS roles through a specialized research project. They often enhanced research and scholarly skills through ethics and research participation and improved interdisciplinary collaborative skills through interactions with team members practicing in education, health care, and research.

The interdisciplinary team training key to effective patient care can be difficult to implement within traditional medical education. PMH-DOCH 2 projects promote participation and understanding of the roles and dynamics of interdisciplinary oncology teams. Students cited growth in nonmedical expert skills as a program outcome; they obtained a greater understanding of community supports and resources and the patient’s perspective, enhancing health advocate abilities. Most notably, many were able to interact with patients, hone communication skills, and build experiences that shaped their future careers.

Both qualitative and quantitative survey data were used to assess factors contributing to student’s satisfaction and success in the PMH-DOCH 2 program. Result trustworthiness is supported by a strong survey response (40.2 %) from former students often many years post-graduation. Especially disgruntled or satisfied students may have responded, but good opinion diversity existed. Due to survey anonymity, we do not know why certain individuals did not respond, possibly biasing study results. Approximately 25 % of DOCH 2 course projects annually are self-initiated and, therefore, more personally tailored to individual students’ educational goals and objectives; 90 % of respondents had catalogue projects and may arguably be less satisfied with projects less tailored to future careers. Recall bias may limit the study; some graduates were reflecting on experiences from 6 to 10 years ago. Respondents’ perceptions of their skills may have changed, rather than the skills themselves. However, these graduates bring a valuable long-term view of program impact. Finally, self-reports on variables, such as increased ability to conduct research, could be more objectively measured using other means in the future.

PMH-DOCH 2 program strengths include multidisciplinary project teams, patient interaction, and opportunities for students to develop research projects as well as to present or publish findings. Student’s concerns included excessive time commitment and lack of supervisor training, which are being addressed in the course by reducing numbers of mandatory tutorials and lectures, increasing support for research question development by students, and enhancing faculty development and supervisor support. Many students seemed to benefit more from self-initiated projects than those from the course catalogue. The PMH-DOCH 2 program enhanced the development of CanMEDS competencies, facilitated career exploration, and provided opportunities for patient interaction, shadowing physicians and working with allied health professionals. Given the overall PMH-DOCH 2 program success, a second hospital course partnership was established in 2006 with Toronto East General Hospital, a local community hospital. A longer-term goal will be to evaluate the DOCH program’s impact on the development of research capacity and outputs among health-care faculty and staff.

References

Frank JR (Ed) (2005) The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, p 37. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/resources/publications/framework_full_e.pdf

Eaton DG, Thong YH (1985) The Bachelor of Medical Science research degree as a start for clinician-scientists. J Med Educ 19(6):445–451

Frishman WH (2001) Student research projects and theses: should they be a requirement for medical school graduation? Heart Dis 3(3):140–144

Reinders JJ, Kropmans TJ, Cohen-Schotanus J (2005) Extracurricular research experience of medical students and their scientific output after graduation. J Med Educ 39(2):237

Solomon SS, Tom SC, Pichert J, Wasserman D, Powers AC (2003) Impact of medical student research in the development of physician-scientists. J Investig Med 51(3):149–156

Richardson WM, Wilson MC, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Nishikawa J (1999) Users guide to medical literature. JAMA 281:1214–1219

University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine (2011). Program. In Undergraduate medical education, University of Toronto. November 2011. http://www.md.utoronto.ca/program.htm. Accessed 7 Oct 2013

Jones J, Nyhof-Young J, Friedman A, Catton P (2001) More than just a pamphlet: development of an innovative computer-based education program for cancer patients. J Patient Educ Couns 44(3):271–281

Princess Margert Hospital (2011). Survivorship program. http://www.survivorship.ca/. Accessed November 18, 2013

ELLISCR (2011). Health wellness and cancer survivorship. http://www.ellicsr.ca Accessed November 18, 2013

Toubassi D, Himel D, Winton S, Nyhof-Young J (2006) The informational needs of newly diagnosed cervical cancer patients who will be receiving combined chemoradiation treatment. J Cancer Educ 21(4):263–268

MacCulloch R, Donaldson S, Nicholas D, Nyhof-Young J, Hetherington R, Lupea D, Wright J (2009) Towards an understanding of the information and support needs of surgical adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients: a qualitative analysis. Scoliosis 4:12–21

Wong J, Mendelsohn D, Nyhof-Young J, Bernstein M (2011) A qualitative assessment of the supportive care and resource needs of patients undergoing craniotomy for benign brain tumours. Support Care Cancer 19(11):1841–1848

Tullio-Pow S, Schaefer K, Zhu R, Kolenchenko O, Nyhof-Young J. Sweet dreams: needs assessment and prototype design of post-mastectomy sleepwear. Peer Reviewed Proceedings of Include 2011: The Role of Inclusive Design in Making Social Innovation Happen. http://include11.kinetixevents.co.uk/4dcgi/prog?operation=detail&paper_id=378

Sterling L, Nyhof-Young J, Blanchette VS, Breakey VR (2011) Exploring Internet needs and use among adolescents with haemophilia: current practices and insights into website desirability features. Haemophilia 18(2):216–221. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02613.x

Brame D, Kolin D, Chung P, Nyhof-Young J (2011) Don’t forget to check your comics! Developing ‘novel’ resources to educate young men about testicular cancer. Intern J Comic Art 13:441–457

Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Frasca E, Nyhof-Young J, Secord S, Walton T, Catton P (2010) The role of a clinician-led reflective interview on improving self-efficacy in breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. J Cancer Educ 25(3):457–463

Taggart L, Ozolins L, Hardie H, Nyhof-Young J (2009) Look good feel better workshops: a ‘big lift’ for women with cancer. J Cancer Educ 24(2):94–99

Chung AD, Ng D, Wang L, Garraway C, Bezjak A, Nyhof-Young J, Wong RKS (2009) Informational stories: a complementary strategy for patients and caregivers with brain metastases. Curr Oncol 16(3):174–179

Kitamura C, Garraway C, Ng D, Chung A, Damaraju D, Bezjak A, Millar B-A, Levin W, Mclean M, Dinniwell R, Nyhof-Young J, Wong R (2011) Messages in a story: evaluation of a combined story and fact based educational booklet for patients with brain metastases and their caregivers. J Palliat Med 25(6):642–649

Sze J, Marisette S, Williams D, Nyhof-Young J, Crooks D, Husain A, Bezjak A, Wong R (2006) Decision making in palliative radiation therapy: reframing hope in caregivers and patients with brain metastases. Support Care Cancer 14(10):1055–1063

Kirkpatrick D (1967) Evaluation of Training. In: Craig R, Bittel L (eds) Training and development handbook. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 131–167

IBM Corp. Released (2010) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. IBM Corp, Armonk

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fernando, E., Jusko-Friedman, A., Catton, P. et al. Celebrating 10 Years of Undergraduate Medical Education: A Student-Centered Evaluation of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre—Determinants of Community Health Year 2 Program. J Canc Educ 30, 225–230 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0674-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0674-2