Abstract

The present study aimed to: (a) investigate the relationship between attitudes toward same-sex parenting and sexism both in heterosexuals and sexual minorities; (b) verify whether sexism predicted negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting via the mediating role of sexual stigma (sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and internalized sexual stigma [ISS] in lesbians and gay men [LG]). An Italian sample of 477 participants (65.6% heterosexual people and 34.4% LG people) was used to verify three hypotheses: (a) heterosexual men showed higher levels of sexism than heterosexual women and LG people; (b) heterosexual men reported more negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting than those of heterosexual women and LG people; and (c) sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and ISS in LG people mediated the relationship between sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Overall, men and heterosexual people showed stronger sexist tendencies and more negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Moreover, sexism affected attitudes toward same-sex parenting via sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and ISS in LG people. These results suggest that negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting reflect sociocultural inequalities based on the traditional gender belief system and points to the necessity of social policies to reduce prejudice toward sexual minority groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sexism is a system of inequality based on gender, which involves beliefs and discriminatory treatment about the superiority and privileges of men (Brown 2010; Eagly & Wood 1999). Glick and Fiske (1996, 2001) presented a theory of sexism based on ambivalence toward women and validated a corresponding measure, the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI). According to the authors, sexism is a multidimensional construct that encompasses two types of attitudes: “Hostile sexism” is an antipathy toward women who are viewed as usurping men’s power, while “benevolent sexism” is a subjectively favorable, chivalrous ideology that offers protection and affection to women who embrace conventional roles.

Despite the greater social acceptability of benevolent sexism, several authors (Glick & Fiske 2001; Sibley & Wilson 2004) have suggested that it serves as a crucial complement to hostile sexism given that it helps to pacify women’s resistance to societal gender inequality. Glick and Fiske (2001) found that benevolent sexism represents a barrier to gender equality (Becker & Wagner 2009; Sibley, Overall, & Duckitt 2007). For example, women who expected benevolent sexism in the workplace had worse performance and results (Dardenne, Dumont, & Bollier 2007); moreover, those who supported benevolent sexism were more likely to accept a sexist male partner who was apparently protective despite a potential negative impact on their career aspirations (Hammond & Overall 2013; Moya, Glick, Expósito, de Lemus, & Hart 2007). The validation studies of the ASI (Glick & Fiske 1996; Glick et al. 2000) have demonstrated that men reported higher levels of hostile sexism than women do; in particular, they showed negative attitudes toward career women and positive attitudes toward housewives because career women deviated from the notion of the ideal of wife and mother (Oliveira Laux, Ksenofontov, & Becker 2015; Rudman 2005). It also emerged that benevolent sexism is more common than hostile sexism, and even if women reject hostile sexism, they tend to accept its benevolent form in line with the system-justification theory (Jost, Burgess, & Mosso 2001; Pacilli, Taurino, Jost, & Van Der Toorn 2011). In this sense, women seem to adhere to the sociocultural system that implicitly establishes their inferiority. Barreto and Ellemers (2005) even have shown that benevolent sexism is not perceived as a form of prejudice by men or women but is viewed positively.

Furthermore, several authors supported the idea that sexual orientation is an important variable to take into account to predict sexist attitudes (Basow & Johnson 2000; Davies 2004). In particular, empirical studies found that heterosexual men showed higher levels of sexism than those of women and sexual minorities (Nagoshi et al. 2008; Warriner, Nagoshi, & Nagoshi 2013). Likewise, gay men, due to the greater threat to their dominant social role, reported a greater degree of sexism than that of lesbian women. One explanation is that the mechanism of sexism does not change in men, regardless of their sexual orientation (Warriner et al. 2013). Interestingly, in those nations where men had high scores of sexism, women seemed to embrace the sexism. In addition, sexism was significantly related to lower levels of education and standards of living, precarious works for women, poor power roles, and minor career ambitions (Glick et al. 2000).

Sexism and Sexual Stigma: Sexual Prejudice and Internalized Sexual Stigma

Sexism is also frequently associated with sexual stigma, which is defined as a cultural belief system through which homosexuality is discredited or disregarded (Aosved & Long 2006; Davies 2004; Sakalli 2002; Whitley 2001). Sexual stigma is defined in this context as the “negative regard, inferior status, and relative powerlessness that society collectively accords anyone associated with nonheterosexual behaviors, identity, relationships, or communities” (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan 2009, p. 33). This phenomenon has also been labeled homophobia, homonegativity, and heterosexism, and like other forms of stigma, it pervades societal customs, institutions, and individuals.

Given the different facets of the term sexual stigma, a conceptual clarification is needed. In this context, when referring to sexual stigma that heterosexual people internalize about sexual minorities, we used the term sexual prejudice, while we used the term internalized sexual stigma (ISS) when referring to homosexual people who internalize society’s negative ideology about sexual minorities. Sexual prejudice involves individual hostility, dislike, and negative attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men, whereby it is congruent with the stigmatizing responses of society (Herek 2007; Lingiardi, Baiocco & Nardelli 2012). As argued by several authors (Herek & McLemore 2011; Mange & Lepastourel 2013; Nagoshi et al. 2008), higher levels of sexism were related to greater levels of sexual prejudice expressed against sexual minority people. In fact, research has shown that people with strong traditional beliefs in gender roles are more likely to endorse sexist views (Glick & Fiske 1996) and homophobic attitudes (Capezza 2007; Costa, Peroni, Bandeira, & Nardi 2013). Similarly, researchers (Herek et al. 2009; Herek 2007; Lingiardi 2012; Meyer & Dean 1998) found that ISS includes a set of negative attitudes and hostile feelings both toward homosexuality in other persons and toward themselves as nonheterosexual people. Societal institutions—including economic, educational, family, and religious institutions—incorporate, legitimate, and perpetuate sexual stigma and the differentials in status and power that it creates. Moreover, these society-level ideologies and patterns of institutionalized oppression of sexual minority people promote heterosexual assumptions (i.e., all people are presumed to be heterosexual), and when people with a nonheterosexual orientation become visible, sexual stigma problematizes them (Herek 2007). Heterosexual people are considered to be the prototypical members of the category of people, and only their behaviors or different-sex relationships are presumed to be normal and natural (Hegarty & Pratto 2001). Even children internalize sexual stigma and grow up with the social expectation to become heterosexual, recognizing homosexuality as socially devalued (Altemeyer 2002).

A theoretical framework that has been used to understand the impact of stigma on lesbian, gay, and bisexual people is the minority stress model (MSM), in which the stigma, prejudice, and experiences of discrimination constitute unique, chronic, psychosocial stressors: “Minority stress arises not only from negative events but from the totality of the minority person’s experience in dominant society” (Meyer, 1995, p. 39). More precisely, minority stress processes are caused by external objective conditions, such as discrimination and violence, expectations of rejection and discrimination, and a more subjective status, such as ISS (Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirratt 2009; Meyer 1995 2003). The most insidious effect of the minority stress processes upon the lesbian, gay, and bisexual people is ISS (Meyer 2003). Several studies have shown that minority stress is correlated with negative effects on physical (Diamant & Wold 2003; Sandfort, Bakker, Schellevis, & Vanwesenbeeck 2006) and psychological health (Cochran & Mays 2006; D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington 1998; Herek & Garnets 2007; Meyer 1995).

In empirical literature about sexual minorities, only a few studies investigated the association between ISS and sexism. Piggott (2004) found a significant positive correlation in a group of 803 lesbian women who resided in Australia, the USA, Canada, Finland, and the United Kingdom. In this research, lesbian women who reported higher levels of sexism also showed greater ISS, depression, and lower self-esteem. Warriner et al. (2013) found a similar result in a sample of 30 lesbian women and 30 gay men undergraduate students. Specifically, the authors revealed that benevolent sexism was positively related to higher levels of ISS for lesbian women and not for gay men. No significant positive correlation between hostile sexism and ISS in lesbian women nor between sexism (hostile and benevolent) and ISS in gay men could be explained by the small sample size of the lesbian women and gay men. Surprisingly, to our knowledge, no other previous study has investigated the association between ISS and sexism in a sample of sexual minorities.

Attitudes Toward Lesbian and Gay Parenting: Gender and Sexual Orientation

A relevant proportion of heterosexual people is against same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting and shows a strong sexual prejudice because same-sex parenting violates their gender expectations (Capezza 2007; Stephan & Stephan 2000). High levels of sexual prejudice are mostly evident in heterosexual men (D’Augelli & Rose 1990; Lingiardi et al. 2016; Massey 2008) who tend to reject homosexuality (McVeigh & Maria-Elena 2009). D’Amore, Green, Scali, Liberati, and Haxhe (2014) examined the correlates of the attitudes toward same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting in a group of 3663 heterosexual Belgian people. They hypothesized that being women, low religiosity, liberal political ideology, and a higher degree of education and socioeconomic status were associated with more positive attitudes. Their findings were substantially consistent with the hypotheses showing that women had a significantly more favorable view of same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting than that of men (Costa & Davies 2012; Cullen, Wright, & Alessandri 2002). Overall, convergent research has indicated that heterosexual people who have a lower education and socioeconomic status as well as higher levels of political conservatism, religious involvement, poor interpersonal contact with lesbian women and gay men, and traditional beliefs about gender roles and family were the most likely to hold negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting and same-sex marriage (Costa, Pereira, & Leal 2015; Crawford, McLeod, Zamboni, & Jordan 1999; D’Amore et al. 2014; Frias-Navarro, Monterde-i-Bort, Pascual-Soler, & Badenes-Ribera 2015; Lingiardi et al. 2016; Schwartz 2010).

Studies have shown that even lesbians and gay men, like heterosexuals, may have negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage (Baiocco, Argalia, & Laghi 2012; Doyle, Rees, & Titus 2015; Egan & Sherrill 2005; Tamagawa 2016), same-sex parenting, and the development of children who grow up in same-sex families (Patterson & Riskind 2010; Petruccelli, Baiocco, Ioverno, Pistella, & D'Urso 2015; Riskind & Patterson 2010; Trub, Quinlan, Starks, & Rosenthal 2016). The majority of studies showed that greater ISS was associated with more negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting in sexual minorities (Baiocco et al. 2012; Pacilli et al. 2011; Trub et al. 2016). In an Italian sample of 197 lesbian women and 176 gay men, Baiocco et al. (2012) found that about half of the participants with a high level of ISS expressed a negative attitude toward same-sex marriage. In an Italian sample of lesbian women and gay men, Pacilli et al. (2011) demonstrated that high levels of ISS and political conservatism led to a more negative attitude toward same-sex parenting. Other studies (Frost 2011; Trub et al. 2016) have confirmed that a high degree of ISS, low self-disclosure to family, political conservatism, and low education are positively correlated with a negative attitude toward same-sex family legalization in lesbian women and gay men. Another variable that could influence negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting is sexism since they are correlated to discriminatory and heterosexist tendencies based on the conformity to traditional gender belief systems (Lingiardi et al. 2012; Whitley 2001). Homosexuality represents a threat to these beliefs about the rigid distinction between genders and between male and female role norms as well as the traditional institution of the family. Hostile attitudes of lesbians and gay men toward same-sex parenting can be encouraged and justified by these sexist values and norms and promote the internalization of ISS in lesbians and gay men as well as social marginalization and disparities in civil rights (Baiocco et al. 2012). Despite the relevance of these topics, little research has investigated the relationship between sexism and negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting.

The Current Study

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2011) found that attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men were different between EU member states. In that research, Italy was among the countries with the highest percentage of people who thought that gay and lesbian parenting harms children (Baiocco & Laghi 2013). Only 44% of Italian respondents were favorable to the legalization of same-sex parenting, and 19% of them supported the possibility of lesbian women or gay men adopting children. A similar result was found by Takács, Szalma, and Bartus (2016): Italy was a country that was opposing the idea of same-sex adoption. In Italy, this trend of negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting could be explained by the fact that there is not a law that regulates unions between persons of the same sex, and it is not permitted for same-sex couples to have children. Despite this legal gap, same-sex parenting is a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly visible in the Italian context (Baiamonte & Bastanioni 2015; Petruccelli et al. 2015). It is therefore essential to investigate potential predictors of negative attitudes.

Currently, little attention has been paid by Italian researchers to the relationship between attitudes toward lesbian and gay parenting and sexism. A few studies (McCutcheon & Morrison 2015; Rye & Meaney 2010) have examined how sexism may influence negative attitudes toward lesbian and gay parenting. In a sample of 447 Canadian undergraduate students (172 men; 275 women), Rye and Meaney (2010) examined the level of sexism and the attitude toward adoption through of scenarios that differed only in regard to the couple’s gender composition (couple of gay men, couple of lesbian women, or couple of heterosexuals). The authors found that heterosexual men had higher levels of sexism (both hostile and benevolent) and were more negative toward adoption by same-sex couples than women, while no differences were found in negative attitudes toward adoption by heterosexual couples. This result was replicated by McCutcheon and Morrison (2015) who asked 506 Canadian university students to evaluate vignettes describing adoptive couples. Also these authors indicated that gay and lesbian couples were rated less favorably than heterosexual couples when asked about outcomes for the adopted child. In particular, these findings were similar to those of participants with a higher level of sexism and traditional gender-related beliefs.

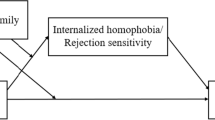

Despite the little research in this field, investigating the effects of sexism on attitudes toward same-sex parenting could be useful to better understand the underlying mechanisms by which these effects operate. In particular, it seems important to study the role of sexual stigma in this context, given that sexual prejudice in heterosexuals as well as ISS in sexual minorities are deeply rooted in sexism and may indirectly promote or increase negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Thus, to complement previous empirical investigations in this area, the current study aimed to examine the relationship between the sexism, sexual stigma (in terms of sexual prejudice and ISS), and the attitudes of heterosexuals and sexual minorities toward lesbian and gay parenting. More in detail, in line with the empirical research mentioned above, our study intended to explore the following hypotheses: heterosexual men will show higher levels of sexism (hostile and benevolent) than those of heterosexual women and sexual minorities (hypothesis 1); heterosexual men will show more negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting than those of heterosexual women and sexual minorities (hypothesis 2); and the relationship between sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting will be mediated by sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and ISS in lesbian women and gay men (hypothesis 3).

Method

Procedures

Participants were recruited through paper questionnaires, advertisements posted on websites, social networks, emailing, and handing out an online link directing them to the survey (hosted by SurveyMonkey). They were from universities, community recreational centers, work places, and sport clubs in Rome, Italy. Since the sexual minority participants were near to 6% of the total sample, other advertisements posted on websites and social networks were directed toward the recruitment of lesbians and gay men. There were no significant differences between groups of lesbian and gay participants with respect to age [t(162) = −.341, p = .576].

We explained to participants that the purpose of this research was to examine the relationship between personality traits and general attitudes in Italian people. It is important to note that the participants did not know the study’s objectives. Inclusion criteria were (a) Italian nationality; (b) self-identified as lesbian, gay, or heterosexual; and (c) age over 18 years. According to these criteria, 15 participants were excluded because their sexual orientation was not gay, lesbian, or heterosexual (twelve bisexuals, three pansexual). Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and participants were encouraged to answer the questions as truthfully as possible. Respondents answered individually to the same questionnaire packet, which included only a different measure of sexual stigma for heterosexuals (sexual prejudice) and sexual minorities (ISS). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. They took about 20 to 25 min to complete the questionnaires. A total of 96% of distributed questionnaires were completely filled in. Before the data collection started, the protocol was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology of the Sapienza University of Rome.

Participants

The participant sample consisted of 477 Italian participants, 294 of whom were women (61.6%), and 183 men (38.4%). They self-identified as lesbian women (17.8%), gay men (16.6%), heterosexual women (43.8%), or heterosexual men (21.8%). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 63 (lesbian women: M = 27.48, SD = 5.67; gay men: M = 28.61, SD = 8.89; heterosexual women: M = 27.68, SD = 8.02; and heterosexual men: M = 27.81, SD = 7.79). Participants had about 15 years of education (lesbian women: M = 14.78, SD = 3.19; gay men: M = 15.47, SD = 3.35; heterosexual women: M = 15.97, SD = 3.37; and heterosexual men: M = 15.12, SD = 2.96). Thus, the general level of education was high, with 42.4% of lesbian women, 40.5% of gay men, 64.1% heterosexual women, and 39.4% of heterosexual men having at least a university degree; while 43.5% of lesbian women, 50.6% of gay men, 28.2% of heterosexual women, and 52.9% of heterosexual men had completed secondary school.

Measures

A background information questionnaire (BIQ) was completed by all the participants to collect data about demographic characteristics such as age and education. Participants were asked to report their sexual orientation by answering an item with four alternative responses (1 = lesbian, 2 = gay, 3 = heterosexual, 4 = other). In the case of the “other” alternative, participants were allowed to specify their sexual orientation.

The D’Amore and Green Same-Sex Parenting Scale (D’Amore et al. 2014; Petruccelli et al. 2015) is a 14-item questionnaire that measures positive attitudes toward same-sex parenting. On a scale of 1 (always wrong) to 5 (never wrong), attitudes toward different forms of the parenting of lesbians and gay men are assessed: adoption by single lesbian women or single gay men, adoption by lesbian or gay couples, alternative or artificial insemination in lesbian women, and in vitro and ovocyte donation to gay men. We used the total scores of the scale for all of the analyses, where a higher score indicated greater positive attitudes toward same-sex parenting. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values was 0.94 (attitudes toward same-sex parenting).

The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick & Fiske, 1996) is a 22-item measure designed to assess sexist attitudes toward women. The two scales of sexism, hostile (e.g., “women seek to gain power by getting control over men”) and benevolent (e.g., “many women have a quality of purity that few men possess”) are assessed separately. A total score for each of the two scales derived from the 6-point Likert-type scale ranged from 0 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly), whereby a higher score indicated greater sexism. A total ASI score was derived from the average of all items. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.72 (hostile sexism [HS]), 0.76 (benevolent sexism [BS]), and 0.81 (total ASI).

The Measure of the Internalized Sexual Stigma for Lesbians and Gay Men (MISS-LG; Lingiardi et al. 2012) is a 17-item questionnaire (e.g., “I would prefer to be heterosexual” or “At university and/or at work, I pretend to be heterosexual”) designed to assess negative attitudes that lesbians and gay men have toward homosexuality in general and toward such aspects of themselves. A total score derived from the 5-point Likert-type scale ranged from 1 (I agree) to 5 (I disagree), whereby a higher score indicated greater ISS. We used the total scores of the scale for all of the analyses. Preliminary studies using the total score indicated good internal consistency. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.85. Descriptive statistics of the measures (MISS-LG) are shown in Table 1.

The Modern Homophobia Scale-R (MHS; Lingiardi et al. 2016) is comprised of 46 items which enable the assessment of attitudes of heterosexual people toward lesbian women (MHS-L, 24 item) and gay men (MHS-G, 22 item). The two forms of the MHS (MHS-L and MHS-G) were highly correlated at r = 0.92. Several studies revealed that the MHS could be used as a measure of attitudes toward both lesbian women and gay men (Burkard, Medler & Boticki 2001; Klotzbaugh & Spencer 2014; Lannutti & Lachlan 2007; McGeorge, Carlson, & Toomey 2015). Thus, we used the total score of the scale for all analyses. A total score derived from the 5-point Likert-type scale ranged from 1 (I disagree) to 5 (I agree), where a higher score indicated greater sexual prejudice toward lesbian women and gay men. The scale includes items such as “seeing a couple of men who are holding hands bothers me” or “gay men could become heterosexual if they wanted.” The MHS-LG has been found to possess excellent scale score reliability. In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.96. Descriptive statistics of the measures (MHS-LG) are shown in Table 1.

Data Analysis

To conduct bivariate and multivariate analyses, we used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0). Group differences (in terms of gender and sexual orientation) on the levels of sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting were analyzed using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r, two-tailed) were performed to examine the associations among sexism, attitudes toward same-sex parenting, and ISS in sexual minorities as well as sexual prejudice in heterosexual people. Moreover, we examined different mediation models to test specific mechanisms that underlie the relationship between sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Mediation occurs when an independent variable has an effect on a dependent variable via a third (mediating) variable (Hayes 2009; MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood 2007). In our analyses, we intended to assess the impact of sexism on attitudes toward same-sex parenting via sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and ISS in lesbians and gay men. We also examined moderated mediation models to verify the effect of gender. We evaluated the direct and mediating effects for statistical significance and applied bootstrapping procedures in accordance with current recommendations and practices in mediation analyses (Hayes 2009). Using the PROCESS SPSS macro (Hayes 2013), regressions were conducted to evaluate all mediation and moderated mediation analyses with bias-corrected bootstrapping using 5000 samples with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Gender and Sexual Orientation Differences in Hostile and Benevolent Sexism

We conducted a 2 (gender: man vs. woman) × 2 (participants’ sexual orientation: heterosexual vs. gay and lesbian) MANOVA on hostile sexism (HS) and benevolent sexism (BS) scores (hypothesis 1). The analysis revealed a significant effect for gender, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.97; F(2,472) = 6.51; p < 0.01, η p 2 = 0.03, and sexual orientation, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.96; F(2,472) = 10.90; p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.04, and no significant effect on gender x sexual orientation, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.99; F(2,472) = 0.48; p = 0.62, η p 2 = 0.002. There was a more significant difference between the scores of men than those of women and between heterosexual and sexual minority participants. In general, men showed higher levels of HS, F(1,473) = 12.49; p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.03, but not BS, F(1,473) = 1.06; p = 0.30, η p 2 = 0.002, than those of women. Conversely, heterosexual people showed higher levels of HS, F(1,473) = 21.19; p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.05, and BS, F(1,473) = 8.47; p < 0.01, η p 2 = 0.02, than sexual minority people. Mean and standard deviations are shown in Table 2. These results showed significant main effects but no significant interaction effect. Thus, men, regardless of sexual orientation, reported higher levels of hostile sexism than those of women; likewise, heterosexual people, regardless of the gender, reported higher levels of sexism (hostile and benevolent) than sexual minorities.

Gender and Sexual Orientation Differences in Same-Sex Parenting

We conducted a 2 (gender: man vs. woman) × 2 (participants’ sexual orientation: heterosexual vs. gay and lesbian) ANOVA on attitudes toward same-sex parenting (hypothesis 2). The analysis produced the expected two-way interaction between gender and sexual orientation, F(1,473) = 4.28; p = 0.04, η p 2 = 0.01 (Table 3).

A simple effect analysis showed that heterosexual men had more negative attitudes about same-sex parenting than those of heterosexual women, and the mean difference was significant, F(1,473) = 15.49, p < 0.001; η p 2 = 0.03; while the mean difference between gay men and lesbian women was not significant, F(1,473) = 0.17, p = 0.68; η p 2 < 0.001. Furthermore, heterosexual men had more negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting than those of gay men, and the mean difference was significant, F(1,473) = 19.95, p < 0.001; η p 2 = 0.04. Interestingly, the mean difference between the heterosexual women and lesbian women was significant, F(1,473) = 4.05; p = 0.04, η p 2 = 0.01. The findings are shown in Fig. 1.

Attitudes Toward Same-Sex Parenting: a Mediation Analysis

To examine the relationship between sexism, attitudes toward same-sex parenting, and sexual prejudice in heterosexual people as well as ISS in lesbian women and gay men, we performed bivariate correlations (Table 4). The results showed that positive attitudes toward same-sex parenting were negatively related to sexism (hostile and benevolent) and sexual prejudice in the heterosexual sample. Likewise, we found that positive attitudes toward same-sex parenting were negatively related to sexism (hostile and benevolent) and ISS in the sexual minority sample.

To investigate whether the relationship between sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting was mediated by sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and ISS in sexual minorities (hypothesis 3), we tested various mediation models. First, we performed mediation analyses taking into account the two subscales of sexism (HS and BS) that correlated moderately. Since these analyses did not yield a different pattern of results, we used the total score of sexism (ASI total score) in mediation models.

In the heterosexual sample, the results showed that sexism (ASI total score) and sexual prejudice (MHS-LG) accounted for a significant amount of variance in attitudes toward same-sex parenting, F(2, 310) = 94.72, p ≤ 0.001, R 2 = 0.38 (see Fig. 2). When examining the relationship of sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting, we found a significant direct effect (B = −0.38, standard error (SE) = 0.07, p ≤ 0.001). When examining this relationship via sexual prejudice, the direct effect was no longer significant, while there was a significant indirect effect (bootstrapping estimate = −0.27, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = −0.37, −0.19). The individual paths revealed that sexism was positively related to sexual prejudice (B = 0.46, SE = 0.07, p ≤ 0.001) and that sexual prejudice was negatively related to positive attitudes toward same-sex parenting (B = −0.59, SE = 0.05, p ≤ 0.001). In regard to the effect of gender, there were no significant findings.

In the sexual minority group, the results showed that sexism and ISS accounted for a significant amount of variance in attitudes toward same-sex parenting, F(2, 161) = 16.69, p ≤ 0.001, R 2 = 0.17 (see Fig. 3). When examining the relationship of sexism on attitudes toward same-sex parenting, we found a significant direct effect (B = −0.13, SE = 0.04, p ≤ 0.001). When examining this relationship via ISS, the direct effect was no longer significant, while there was a significant indirect effect (bootstrapping estimate = −0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = −0.10, −0.04). The individual paths revealed that sexism was positively related to ISS (B = 0.23, SE = 0.05, p ≤ 0.001), and ISS was negatively related to positive attitudes toward same-sex parenting (B = −0.25, SE = 0.06, p ≤ 0.001). In regard to the effect of gender, there were no significant findings.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate attitudes toward same-sex parenting in heterosexuals and sexual minorities while examining the impact of sexism and sexual stigma. This research intended to fill a gap in the literature and extend knowledge about attitudes toward same-sex parenting while also taking into account the perspective of lesbian and gay people, who have rarely been investigated in this topic’s literature. Interestingly, recent contributions have indeed demonstrated that even people belonging to sexual minorities have negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage and parenting (Baiocco et al. 2012; Herek et al. 2009; Patterson & Riskind 2010; Szymanski, Chung, & Balsam 2001).

The first aim of the research was to verify if heterosexual men showed higher levels of sexism than those of heterosexual women and sexual minorities. The findings partially confirmed our hypothesis, while the interaction effects between gender and sexual orientation on both hostile and benevolent sexism were not significant; the main effects of these variables were significant and meaningfully consistent with the scientific international literature. In detail, as often reported in the previous studies (Davies 2004; Glick & Fiske 1996; Glick et al. 2000), we found only a significant effect of gender (men reported a higher level of sexism than that of women) and sexual orientation (heterosexual people showed a higher level of sexism than that of sexual minorities). These differences could reflect sociocultural inequalities and discriminatory behaviors based on the traditional gender belief system and the ideology embodied in institutional practices that work to the disadvantage of sexual minority groups (Herek et al. 2009).

Another aim of this study was to examine if heterosexual men showed more negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting than those of heterosexual women and sexual minorities. The findings completely confirmed our hypothesis: heterosexual men’s attitudes toward same-sex parenting were more negative than those of heterosexual women and sexual minorities, and heterosexual women’s attitudes toward same-sex parenting were more negative than those of lesbian women, thereby suggesting the strong influence of heteronormative assumptions related to stereotypes of the traditional family (Whitley & Kite 2009, pp. 479–489) and stronger prejudice due to parents’ sexual orientation (Barrientos, Cárdenas, Gómez, & Frías-Navarro 2013).

Moreover, this study examined whether negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting were significantly associated with sexism (HS and BS) and sexual stigma. Results were in line with previous research (Baiocco, Nardelli, Pezzuti, & Lingiardi 2013; Brumbaugh, Sanchez, Nock, & Wright 2008; Capezza 2007; Herek 2002; Herek et al. 2009; Hollekim, Slaatten, & Anderssen 2012; Lingiardi et al. 2012; Stephan & Stephan 2000). Negative attitudes about same-sex parenting were associated with sexism and were strongly connected to both sexual prejudice in heterosexuals (Capezza 2007; Stephan & Stephan 2000) and ISS in lesbian women and gay men (Baiocco et al. 2012; Lingiardi et al. 2012; Pacilli et al. 2011). These results suggest that discrimination and prejudice arouse negative attitudes, regardless of gender or sexual orientation (Baiocco et al. 2015; Barrientos et al. 2013; Davies 2004; Petruccelli et al. 2015; Pistella, Salvati, Ioverno, Laghi, & Baiocco 2016; Salvati, Ioverno, Giacomantonio, & Baiocco 2016).

Looking in more detail at the mediation models that we tested to verify the last hypothesis of the study, it is important to note that the relationship between sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting was mediated both by sexual prejudice in heterosexual people and ISS in lesbian and gay people. These findings have remarkable implications in understanding the underlying mechanisms of negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Moreover, the indirect effect of sexism on negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting via sexual prejudice in the heterosexual sample was larger than the indirect effect of sexism on negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting via ISS in the sexual minority sample. However, these results support the possibility that sexual stigma, more than sexism, was able to legitimate and perpetuate ideological systems that promote greater negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting (Capezza 2007; Lingiardi et al. 2016).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study had some limitations. First, it was based on a convenience sample that may limit the generalizability of the results (Schumm 2015). Indeed, the use of a convenience sample can never truly access a representative sample of individuals. A second limitation regards the use of self-report instruments that may be influenced by social desirability or other ideological biases. Moreover, the study was conducted in Italy, and these findings may not apply to sexual minorities and heterosexual people living in other countries. Future research could include measures designed to evaluate individuals’ implicit beliefs such as the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji 2003) or the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Stewart, & Boles 2010). In the end, this study did not consider other variables that could have an influence on negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting, such as interpersonal contact (Costa et al. 2015) or an individual’s political ideology or religious involvement (Baiocco et al. 2012; Crawford et al. 1999; D’Amore et al. 2014). Future research could examine these important variables.

Conclusion

This study was conducted given that only a few empirical studies on attitudes toward same-sex parenting have investigated the crucial role of sexism and sexual stigma in perpetuating prejudice, hostility, and discrimination toward lesbian women and gay men. It would be important to promote initiatives and projects (such as antidiscrimination policies, social issues advertising, educational projects, and granting civil rights to all citizens, including same-sex marriage and parenting) aimed at reducing social disparities and fostering cultural changes, especially in countries such as Italy that are characterized by high levels of sexism and stigma around homosexuality (Lingiardi et al. 2016; Salvati et al. 2016). Findings of the present study suggest that it is necessary to examine not only heterosexual people as potential actors of negative attitudes but also to take into account the negative attitudes of sexual minorities toward their same minority group.

References

Altemeyer, B. (2002). Changes in attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 63–75.

Aosved, A. C., & Long, P. J. (2006). Co-occurrence of rape myth acceptance, sexism, racism, homophobia, ageism, classism, and religious intolerance. Sex Roles, 55, 481–492.

Baiamonte, C., & Bastanioni, P. (2015). Le famiglie omogenitoriali in Italia. Bergamo: Edizioni Junior.

Baiocco, R., & Laghi, F. (2013). Sexual orientation and the desires and intentions to become parents. Journal of Family Studies, 19, 90–98.

Baiocco, R., Argalia, M., & Laghi, F. (2012). The desire to marry and attitudes toward same-sex family legalization in a sample of Italian lesbians and gay men. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 181–200.

Baiocco, R., Nardelli, N., Pezzuti, L., & Lingiardi, V. (2013). Attitudes of Italian heterosexual older adults towards lesbian and gay parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10, 285–292.

Baiocco, R., Santamaria, F., Ioverno, S., Fontanesi, L., Baumgartner, E., Laghi, F., & Lingiardi, V. (2015). Lesbian mother families and gay father families in Italy: Family functioning, dyadic satisfaction, and child well-being. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12, 202–212.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Stewart, I., & Boles, S. (2010). A sketch of the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) and the relational elaboration and coherence (REC) model. The Psychological Record, 60, 527–542.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 633–642.

Barrientos, J., Cárdenas, M., Gómez, F., & Frías-Navarro, D. (2013). Assessing the dimensionality of beliefs about children’s adjustment in same-sex families scale (BCASSFS) in Chile. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10, 43–51.

Basow, S. A., & Johnson, K. (2000). Predictors of homophobia in female college students. Sex Roles, 42, 391–404.

Becker, J. C., & Wagner, U. (2009). Doing gender differently—The interplay of strength of gender identification and content of gender identity in predicting women’s endorsement of sexist beliefs. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 487–508.

Brown, R. (2010). Prejudice: Its social psychology (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Brumbaugh, S. M., Sanchez, L. A., Nock, S. L., & Wright, J. D. (2008). Attitudes toward gay marriage in states undergoing marriage law transformation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 345–359.

Burkard, A. W., Medler, B. R., & Boticki, M. A. (2001). Prejudice and racism: Challenges and progress in measurement. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 457–481). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Capezza, N. M. (2007). Homophobia and sexism: The pros and cons to an integrative approach. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 41, 248–253.

Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2006). Estimating prevalence of mental and substance-using disorders among lesbians and gay men from existing national health data. In A. M. Omoto & H. S. Kurtzman (Eds.), Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people (pp. 143–165). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Costa, P. A., & Davies, M. (2012). Portuguese adolescents’ attitudes toward sexual minorities: Transphobia, homophobia, and gender role beliefs. Journal of Homosexuality, 59, 1424–1442.

Costa, A. B., Peroni, R. O., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2013). Homophobia or sexism? A systematic review of prejudice against nonheterosexual orientation in Brazil. International Journal of Psychology, 48, 900–909.

Costa, P. A., Pereira, H., & Leal, I. (2015). “The contact hypothesis” and attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12, 125–136.

Crawford, I., McLeod, A., Zamboni, B. D., & Jordan, M. B. (1999). Psychologists’ attitudes toward gay and lesbian parenting. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30, 394–401.

Cullen, J. M., Wright, L. W., & Alessandri, M. (2002). The personality variable openness to experience as it relates to homophobia. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 119–134.

D’Amore, S., Green, R. J., Scali, T., Liberati, G., & Haxhe, S. (2014). Belgian heterosexual attitudes toward homosexual couples and families. In J. E. Sokolec & M. P. Dentato (Eds.), The effect of marginalization on the healthy aging of LGBTQ older adults (pp. 18–24). Chicago: Loyola University Chicago: Social Justice Retrevied from http://ecommons.luc.edu/social_justice/51.

D’Augelli, A. R., & Rose, M. L. (1990). Homophobia in a university community: Attitudes and experiences of heterosexual freshmen. Journal of College Stududent Development, 31, 484–491.

D’Augelli, A. R., Hershberger, S. L., & Pilkington, N. W. (1998). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 361–371.

Dardenne, B., Dumont, M., & Bollier, T. (2007). Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 764–779.

Davies, M. (2004). Correlates of negative attitudes toward gay men: Sexism, male role norms, and male sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 259–266.

Diamant, A. L., & Wold, C. (2003). Sexual orientation and variation in physical and mental health status among women. J Women’s Health, 12, 41–49.

Doyle, C. M., Rees, A. M., & Titus, T. L. (2015). Perceptions of same-sex relationships and marriage as gender role violations: An examination of gendered expectations (sexism). Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 1576–1598.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior. American Psychologist, 54, 408–423.

Egan, P. J., & Sherrill, K. (2005). Marriage and the shifting priorities of a new generation of lesbians and gays. Political Science and Politics, 38, 229–232.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2011). European Union Agency for fundamental rights | helping to make fundamental rights a reality for everyone in the European Union. Retrieved from http://fra.europa.eu/en.

Frias-Navarro, D., Monterde-i-Bort, H., Pascual-Soler, M., & Badenes-Ribera, L. (2015). Etiology of homosexuality and attitudes toward same-sex parenting: A randomized study. The Journal of Sex Research, 52, 151–161.

Frost, D. M. (2011). Similarities and differences in the pursuit of intimacy among sexual minority and heterosexual individuals: A personal projects analysis. Journal of Social Issues, 67, 282–301.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., … López, W. L. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 197–216.

Hammond, M. D., & Overall, N. C. (2013). When relationships do not live up to benevolent ideals: Women’s benevolent sexism and sensitivity to relationship problems. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 212–223.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford.

Hegarty, P., & Pratto, F. (2001). Sexual orientation beliefs: Their relationship to anti-gay attitudes and biological determinist arguments. Journal of Homosexuality, 41, 121–135.

Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66, 40–66.

Herek, G. M. (2007). Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: Theory and practice. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 905–925.

Herek, G. M., & Garnets, L. D. (2007). Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 353–375.

Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. A. (2011). Sexual Prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333.

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 32–43.

Hollekim, R., Slaatten, H., & Anderssen, N. (2012). A nationwide study of Norwegian beliefs about same-sex marriage and lesbian and gay parenthood. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 9, 15–30.

Jost, J. T., Burgess, D., & Mosso, C. O. (2001). Conflicts of legitimation among self, group, and system: The integrative potential of system justification theory. In J. Jost & B. Major (Eds.), The psychology of legitimacy (pp. 363–390). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kertzner, R. M., Meyer, I. H., Frost, D. M., & Stirratt, M. J. (2009). Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: The effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 500–510.

Klotzbaugh, R., & Spencer, G. (2014). Magnet nurse administrator attitudes and opportunities: Toward improving lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender–specific healthcare. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44, 481–486.

Lannutti, P. J., & Lachlan, K. A. (2007). Assessing attitude toward same-sex marriage: Scale development and validation. Journal of Homosexuality, 53, 113–133.

Lingiardi, V. (2012). Citizen gay. Affetti e diritti [gay citizen: Affections and rights]. Milano: Saggiatore.

Lingiardi, V., Baiocco, R., & Nardelli, N. (2012). Measure of internalized sexual stigma for lesbians and gay men: A new scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 59, 1191–1210.

Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Ioverno, S., Falanga, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Tanzilli, A., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Homonegativity in Italy: Cultural issues, personality characteristics, and demographic correlates with negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13, 95–108.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C. M. (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 384–389.

Mange, J., & Lepastourel, N. (2013). Gender effect and prejudice: When a salient female norm moderates male negative attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 1035–1053.

Massey, S. G. (2008). Sexism, heterosexism, and attributions about undesirable behavior in children of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual parents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 3, 457–483.

McCutcheon, J., & Morrison, M. A. (2015). The effect of parental gender roles on students’ attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive couples. Adoption Quarterly, 18, 138–167.

McGeorge, C. R., Carlson, T. S., & Toomey, R. B. (2015). An exploration of family therapists’ beliefs about the ethics of conversion therapy: The influence of negative beliefs and clinical competence with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41, 42–56.

McVeigh, R., & Maria-Elena, D. D. (2009). Voting to ban same-sex marriage: Interests, values, and communities. American Sociological Review, 74, 891–915.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697.

Meyer, I. H., & Dean, L. (1998). Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 160–186). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Moya, M., Glick, P., Expósito, F., de Lemus, S., & Hart, J. (2007). It’s for your own good: Benevolent sexism and women’s reactions to protectively justified restrictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1421–1434.

Nagoshi, J. L., Adams, K. A., Terrell, H. K., Hill, E. D., Brzuzy, S., & Nagoshi, C. T. (2008). Gender differences in correlates of homophobia and transphobia. Sex Roles, 59, 521–531.

Oliveira Laux, S. H., Ksenofontov, I., & Becker, J. C. (2015). Explicit but not implicit sexist beliefs predict benevolent and hostile sexist behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 702–715.

Pacilli, M. G., Taurino, A., Jost, J. T., & van der Toorn, J. (2011). System justification, right-wing conservatism, and internalized homophobia: Gay and lesbian attitudes toward same-sex parenting in Italy. Sex Roles, 65, 580–595.

Patterson, C. J., & Riskind, R. G. (2010). To be a parent: Issues in family formation among gay and lesbian adults. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6, 326–340.

Petruccelli, I., Baiocco, R., Ioverno, S., Pistella, J., & D'Urso, G. (2015). Famiglie possibili: uno studio sugli atteggiamenti verso la genitorialità di persone gay e lesbiche. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 42, 805–828.

Piggott, M. (2004). Double jeopardy: Lesbians and the legacy of multiple stigmatized identities. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Swinburne University of Technology: Hawthorn.

Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., Laghi, F., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Coming-out to family members and internalized sexual stigma in bisexual, lesbian and gay people. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 3694–3701.

Riskind, R. G., & Patterson, C. J. (2010). Parenting intentions and desires among childless lesbian, gay, and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 78–81.

Rudman, L. A. (2005). Benevolent barriers to gender equity. In C. S. Crandall & M. Schaller (Eds.), Social psychology of prejudice: Historical & contemporary issues (pp. 35–54). Lawrence: Lewinian.

Rye, B. J., & Meaney, G. (2010). Self-defense, sexism, and etiological beliefs: Predictors of attitudes toward gay and lesbian adoption. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6, 1–24.

Sakalli, N. (2002). The relationship between sexism and attitudes toward homosexuality in a sample of Turkish college students. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 53–64.

Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., Giacomantonio, M., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Attitude toward gay men in an Italian sample: Masculinity and sexual orientation make a difference. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13, 109–118.

Sandfort, T. G. M., Bakker, F., Schellevis, F. G., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2006). Sexual orientation and mental and physical health status: Findings from a Dutch population survey. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1119–1125.

Schumm, W. R. (2015). Navigating treacherous waters—One Researcher’s 40 years of experience with controversial scientific research. Comprehensive Psychology, 4, 1–40.

Schwartz, J. (2010). Investigating differences in public support for gay rights issues. Journal of Homosexuality, 57, 748–759.

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696.

Sibley, C. G., Overall, N. C., & Duckitt, J. (2007). When women become more hostilely sexist toward their gender: The system-justifying effect of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, 57, 743–754.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2000). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 23–45). Mahawah: Psychology Press.

Szymanski, D. M., Chung, Y. B., & Balsam, K. F. (2001). Psychosocial correlates of internalized homophobia in lesbians. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34, 27–38.

Takács, J., Szalma, I., & Bartus, T. (2016). Social attitudes toward adoption by same-sex couples in Europe. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 12, 46–67.

Tamagawa, M. (2016). Same-sex marriage in Japan. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12, 160–187.

Trub, L., Quinlan, E., Starks, T. J., & Rosenthal, L. (2016). Discrimination, internalized homonegativity, and attitudes toward children of same-sex parents: Can secure attachment buffer against stigma internalization? Family Process . doi:10.1111/famp.12255.1–15

Warriner, K., Nagoshi, C. T., & Nagoshi, J. L. (2013). Correlates of homophobia, transphobia, and internalized homophobia in gay or lesbian and heterosexual samples. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 1297–1314.

Whitley, B. E. (2001). Gender-role variables and attitudes toward homosexuality. Sex Roles, 45, 691–721.

Whitley, B., & Kite, M. (2009). The psychology of prejudice and discrimination. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the sexual minorities and heterosexuals who participated in this study. All authors who contributed significantly to the work have been identified.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was not funded by any grant.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pistella, J., Tanzilli, A., Ioverno, S. et al. Sexism and Attitudes Toward Same-Sex Parenting in a Sample of Heterosexuals and Sexual Minorities: the Mediation Effect of Sexual Stigma. Sex Res Soc Policy 15, 139–150 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0284-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0284-y