Abstract

The present study is the first meta-analytic study about the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) in self-identified lesbians in same-sex couples. It summarizes the scientific evidence from studies published from 1990 to 2013. First, 1,184 studies were identified, then 59 studies were pre-selected, and finally 14 studies were chosen that met the criteria for inclusion and methodological quality. The studies were conducted in the USA, using non-probabilistic sampling methods, and they were characterized by their high level of heterogeneity. The mean prevalence of victimization in IPV over the lifespan is 48 % (95 % CI, 44–52 %) and 15 % (95 % CI, 5–30 %) in the current/most recent relationship, with the difference being statistically significant between over the lifespan and current/most recent relationship IPV. The mean prevalence of victimization in physical violence over the lifespan is 18 % (95 % CI, 0–48 %), in sexual violence 14 % (95 % CI, 0–37 %), and in psychological/emotional violence 43 % (95 % CI, 14–73 %). The high prevalence suggests the need to implement IPV prevention programs among lesbians, as well as homophobia prevention programs. Moreover, the methodological quality of prevalence studies should be improved. The limited number of studies considered in each thematic block and the high heterogeneity of their results should be taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The study of violence in same-sex couples began at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. At that time, the first books appeared about intimate partner violence in lesbian women (Lobel 1986) and gay men couples (Island and Letellier 1991). The first studies were also published on this topic (Brand and Kidd 1986; Kalichman and Rompa 1995; Renzetti 1988). Since then, there has been a gradual increase in the number of studies that have analyzed violence in same-sex couples. Specifically, research has been carried out in countries like the USA (e.g., Hardesty et al. 2011), Canada (e.g., Barrett and St. Pierre 2013), Australia (Frankland and Brown 2013), Puerto Rico (e.g., Reyes-Mena et al. 2005), Venezuela (e.g., Burke et al. 2002), China (e.g., Chong et al. 2013), and Japan (e.g., DiStefano 2009), among others. However, there is much less information about violence in same-sex couples, and specifically in female couples, than there is about intimate partner violence in heterosexual relationships. This difference is partly due to sampling and methodological problems encountered in studying IPV in female same-sex couples (Lewis et al. 2012).

Studies on victimization surveys with probabilistic samples have generally taken the heterosexuality of the participants for granted, without evaluating their sexual orientation (West 2012), although there have been exceptions (e. g., Goldberg and Meyer 2013; Roberts et al. 2010; Walters et al. 2013). However, in these latter cases, it was assumed that sexual orientation is fixed throughout life, so that the sex of the perpetrator of the intimate partner violence was not evaluated. In other words, there was no evaluation of whether the violence took place in a same-sex couple. Sexual orientation has a certain degree of fluidity over a lifetime (Moradi et al. 2009; Murray and Mobley 2009), so that a subject who self-identifies as a lesbian or gay man may have been involved in a relationship with a partner of the opposite sex (Baker et al. 2013). Therefore, as Murray and Mobley (2009) point out, in studies where it has been assumed that the sex of the partner is the same as that of the self-identified lesbian woman, the reported ratios of violence might be inflated by including violence perpetrated by partners of the opposite sex (e.g., Walters et al. 2013). Thus, it is important to evaluate the sex of the perpetrator, or whether the violence occurred in a relationship between people of the same sex.

In addition, the stigmatized nature of homosexuality and, consequently, same-sex couple relationships makes it difficult to carry out studies with representative samples. Therefore, the majority of the studies on same-sex partner violence have been conducted with small convenience samples. Generally, the participants were recruited through their attendance at musical events and gay pride day events or networks. However, some of these studies did not evaluate the sexual orientation of the participants, taking their homosexuality for granted due to their attendance at these social events (e.g., Lockhart et al. 1994).

In the research on intimate partner violence in same-sex couples, sexual orientation and same-sex relationships are often confused when these questions are asked. Baker et al. (2013) point out that “being involved in same-sex relationships is a behavior, while identifying as a lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender person is an identity” (p. 184). Furthermore, studies suggest that a sexual identity is more strongly associated with victimization and mental health than sexual attraction and sexual behavior are (Roberts et al. 2010). Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate between studies that ask the participants about their sexual orientation (identity) and those that ask about their partner’s sex (sexual behavior) because “not everyone who is involved in a same-sex relationship identifies him/herself as a member of the LGBT community” (Baker et al. 2013, p. 184).

In addition, the experience of intimate partner violence may not be the same for lesbian and bisexual women. Studies suggest that there can be differences in the rates of perpetration and victimization between lesbian and bisexual women (Balsam and Szymanski 2005; Lewis et al. 2012; Gumienny 2010). For example, Messinger (2011) found that lesbians, compared to bisexual women with partners of the same sex, reported higher rates of victimization in the past year involving control behaviors (55.56 vs 6.82 %), verbal aggression (44 vs 13.04 %), physical aggression (25 vs 6.12 %), and sexual abuse (3.57 vs 0 %). However, Goldberg and Meyer (2013) found that bisexual women presented higher rates of intimate partner violence victimization in the past year (27.48 %) and over the lifespan (51.99 %) than lesbians (10.23 and 31.87 %, respectively). Similarly, Roberts et al. (2010) observed a higher prevalence of intimate partner violence victimization in bisexual women (20.17 %) than in lesbians (16.10 %). Moreover, Walters et al. (2013) found that bisexual women had a greater prevalence of all types of partner violence (psychological aggression, physical violence, and sexual violence) than lesbian women and heterosexual women. Thus, 61.1 % of bisexual women had been victims of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime compared to 43.8 % of lesbian women. Consequently, intimate partner violence should be studied separately in lesbians and bisexual women.

Furthermore, the operationalization of the definition of IPV varies across studies (e.g., only one item, lists of different types of violent behaviors, standardized measures). However, asking whether someone has experienced partner abuse is not the same as asking how many times he/she has experienced a certain abusive act (Lewis et al. 2012). Moreover, in the lists of behaviors, sometimes the same conduct can be categorized as different types of violence depending on the study analyzed (e.g., stalking can be psychological violence or physical violence).

In addition, the studies used different time frames (e.g., lifetime, the past year, the past 5 years, current relationship, most recent relationship, etc.), giving rise to great variability in the data. For example, the estimation of the ratios of partner violence experienced over the lifetime will probably be greater than the violence experienced in the past year or in the relationship with the most recent partner.

Finally, the majority of the standardized measures used to evaluate partner violence have been developed and validated in heterosexual samples (e.g., Conflict Tactics Scale, Abusive Behavior Inventory, or Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory), with the exception of psychological aggression on the CTS-2, which has been validated for same-sex couples (Matte and Lafontaine 2011). These IPV measures do not evaluate specific forms of psychological violence in same-sex couples, such as “homophobic control.” The same thing is true of the national surveys with representative samples designed to evaluate partner violence from the viewpoint of heterosexual partner violence (e.g., Walters et al. 2013). “Homophobic control” can be manifested as a behavior of threatening to reveal the partner’s sexual orientation to family, friends, co-workers, employer, and others (Bunker 2006; Renzetti 1992; West 2002) or as behaviors that reinforce internalized homophobia, that is, interiorizing negative attitudes and assumptions about homosexuality (e.g., telling the partner she deserves what she gets because she is a lesbian/gay/bisexual woman). Few researchers have added supplementary items to the standardized measures to reflect these specific forms of psychological aggression that can be found in same-sex couples (e.g., Balsam and Szymanski 2005; Eaton et al. 2008; Scherzer 1998; Turell 2000).

In sum, in spite of the great variability in the ratios of IPV among female same-sex couples, it has been recognized that this problem is urgent and that there can be differences in the ratios of IPV between the different subgroups of women who have sex with women. However, little is known about the antecedents and factors that contribute to maintaining partner violence among women (Lewis et al. 2012). The studies on IPV among female same-sex couples have associated the violence with a power imbalance in the relationship, the partner’s dependence, jealousy, fusion, a history of violence in the family background, consumption and abuse of substances (McClennen 2005; Murray et al. 2007; Peterman and Dixon 2003; West 2002, 2012), and sexual minority stress, specifically with internalized homophobia (Balsam and Szymanski 2005; Carvalho et al. 2011; Gumienny 2010; West 2012).

Therefore, given the disparity in the prevalence rates of violence in lesbian couples, the purpose of our study is to elaborate a systematic and meta-analytic quantitative review of the prevalence of IPV experienced by self-identified lesbians in same-sex relationships in order to use statistical methods to quantitatively integrate the results of the scientific evidence and provide a mean rate of prevalence, taking into account the studies’ sample size and methodological quality.

Method

A systematic and meta-analytic literature review was carried out (Lipsey and Wilson 2001; Monterde-i-Bort et al. 2006).

Inclusion Criteria

The studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) they had to have been published between January 1990 and December 2013, (2) in a peer-reviewed journal; (3) they had to consist of original research; (4) they had to be quantitative studies; (5) they had to have used a sample made up, at least partly, of participants who self-identified as lesbians and/or gay women; (6) the participants who self-identified as lesbians and/or gay women had to be analyzed separately as a group within the study; (7) the participants who self-identified as lesbians and/or gay women had to have formed part of the general population; (8) the studies had to have measured, in some way, intimate partner violence (IPV) between people of the same sex; (9) they had to have reported on the prevalence of intimate partner violence; (10) the sample size had to be equal to or greater than 30; and (11) the participants who self-identified as lesbians and/or gay women had to be 16 years old or more.

Search Strategy

The information search was carried out during the months from August 2013 to January 2014 in the databases of PubMed and PsycInfo using the following terms: intimate partner violence and lesbian, lesbian domestic violence, lesbian violence, lesbian battering, and abusive lesbian relationship. A total of 1,091 studies were identified, of which 487 were from PsycInfo and 604 were from Medline.

Moreover, a manual search was conducted, identifying a total of 92 studies in the publications Journal of Homosexuality; Journal of Lesbian Studies; Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Service; Journal of GLBT Family Studies; Journal of LGBT Health Research; Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling; Journal of interpersonal violence; Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse; and Journal of Family Violence, Psychology of Women Quarterly, Violence Against Women, and Women & Therapy.

Furthermore, a manual review was performed of lists of references from the studies included in this review, from relevant studies on intimate partner violence in lesbian women, and from reviews of the previous literature, locating only one study. Finally, researchers and/or experts on intimate partner violence in same-sex people were contacted.

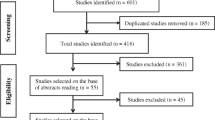

In all, 1,184 studies were identified. Duplicated studies were eliminated (n = 497). Therefore, the total number of studies to be reviewed was 687.

Selection Procedure

The study selection process took place in two phases (pre-selection and selection), both carried out independently by two researchers. To calculate the inter-rater agreement, Cohen’s Kappa was used. In the pre-selection phase, the titles and abstracts of the 687 studies were scanned, and the relevant studies were pre-selected based on the inclusion criteria. The degree of consensus between the reviewers was 90 %. The total number of pre-selected studies was 59.

In the selection phase, the complete text of each of the 59 pre-selected studies was reviewed. The degree of inter-reviewer agreement was 80 %. Given the degree of agreement and to guarantee greater reliability in the study selection, a consensus process was undertaken on those studies where there was disagreement. Forty-four studies were excluded, 2 due to not having the complete text and 42 for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Therefore, 15 primary studies were selected.

Rating the Methodological Quality of the Primary Studies

The 15 studies selected were submitted to a rating of their methodological quality based on the standardized criteria of the “Methodological quality rating guide of descriptive studies on same-sex intimate partner violence” developed by Murray and Mobley (2009). This rating guide is an adaptation of the evaluation criteria for methodological quality used by Heneghan et al. (1996), Murray and Graybeal (2007), and Burke and Follingstad (1999). The evaluation was performed independently by two researchers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the reviewers.

The rating guide consists of 15 criteria with a dichotomous response scale (present or absent). The presence criterion received 1 point, and absence was awarded 0 points. The total score is 15 points. Table 1 shows the consensual scores for the studies on the methodological quality criteria and their total score.

To classify the studies according to their total score on methodological quality, a stratification system was used, similar to the one used by Heneghan et al. (1996), Murray and Graybeal (2007), and Murray and Mobley (2009). Thus, the studies were classified according to their degree of methodological quality on: (1) acceptable studies: studies that receive at least 11 points (70 % of the total score), (2) adequate studies: studies with a score between 6 and 10 points (between 40 and 69 % of the total score), and (3) unacceptable studies: studies that obtained a score between 0 and 5 points (less than 40 % of the total score). This systematic review included the studies rated as “acceptable studies” or “adequate studies.”

None of the studies reviewed were cataloged as acceptable. Only the study by Carvalho et al. (2011) was considered unacceptable, with a score below 40 % of the total, so that it was excluded from the systematic review presented here. The rest of the studies were considered adequate, obtaining a score of between 40 and 69 % of the total, so that they were included in this systematic review.

Data Extraction

The data were extracted from the studies by two reviewers independently. The disagreements were resolved by consensus between the reviewers. Data were extracted on the characteristics of the study (authors and year, study design, location, definition of violence, measurement instrument), the characteristics of the sample (age, educational level, income level), the prevalence of partner violence victimization based on the period recalled and form of violence, and the prevalence of partner violence perpetration based on the period recalled and form of violence.

Data Analysis

To statistically combine the results from the studies, a random effects model was chosen, where there is no a priori assumption of homogeneity in the magnitudes of the prevalence rates, attributing the variability to sampling error and to the variability among the studies. That is, each study is considered to estimate its own population effect size (Hedges 1994; Hedges and Olkin 1985). Moreover, this model is recommended when the number of studies is small (Brockwell and Gordon 2011). To estimate the heterogeneity, the Q statistic was used, completed with the I 2 statistic. The two statistics indicate the proportion of variability observed in the effects due to the heterogeneity among the studies and not to chance. If the Q statistic has a value of p < .05, the effect sizes are heterogeneous. It is usually considered that if I 2 = 25, there is little heterogeneity; if I 2 = 50 %, there is moderate heterogeneity; and when I 2 = 75 %, the heterogeneity is high. One of the advantages of the I 2 statistic is that it is not affected by the number of studies (Higgins and Thompson 2002; Huedo-Medina et al. 2006). Therefore, when the random effects model did not fit adequately (p > .05), we also estimated the mean effect size with the fixed effects model, and the differences between the two models were always minimal. When there were only two articles available to study a given construct, the mean effect size was calculated to improve the score estimation and offer the confidence interval, taking into account that its precision would be quite low. When two studies have been used, the forest plots have not been represented.

The analyses were grouped by thematic blocks of violence, and it was considered that they represent a random sample of effect sizes, with the objective being the calculation of the mean prevalence and its confidence interval. In this sense, the 14 studies were divided into two groups according to the period of recall reported (over the lifespan vs current or more recent relationship, which includes the violence experienced in the past year). Later, the studies were divided into two subgroups according to the measurement instrument used to evaluate the intimate partner violence (standardized instrument vs author’s instrument, e. g., “if you are currently in a lesbian relationship, is it abusive?” or “have you ever been abused by a female lover/partner?”).

The mean prevalence and its confidence interval were calculated for total intimate partner violence victimization and for the different forms of violence (physical, sexual, and psychological/emotional) based on the period of recall (over the lifespan or current or most recent relationship) and the measurement instrument used (standardized or author’s). The mean prevalence and its confidence level for intimate partner violence perpetration were also calculated based on the period of recall (over the lifespan or current or most recent relationship) and the measurement instrument used (standardized or author’s).

To compute the mean prevalence, the MetaXL program was used, which includes the possibility of executing a model by weighting the quality of the estimated effects of the primary studies, which is recommended when heterogeneity is detected in the individual effect sizes (Barendregt et al. 2013; Doi and Thalib 2008).

In the present study, the calculation of the mean prevalence took the methodological quality of the study into account. The total quality score was transformed into a rating scale from 0–1 (relative methodological quality), as this range of scores is permitted by the MetaLX program. To do so, the total quality score obtained by each study was divided by the total scale score (quality of the study/total quality of the scale).

It should be pointed out that not all of the studies included in this systematic meta-analytic review reported on the prevalence of intimate partner violence or one of its forms. Therefore, each analysis in the meta-analysis included a different number of studies, which ranged from four studies to two studies. Given the low number of studies analyzed in each meta-analysis, the results of our study represent the first approach to the phenomenon of intimate partner violence between self-identified lesbians. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out more research on these types of relationships.

Results

The process of selecting the studies is presented in Fig. 1. After the literature search in databases (PubMed and PsycInfo), specialized peer-reviewed journals, lists of references, and contact with experts, 1,184 primary studies were identified. Then, 59 studies were pre-selected, and of them, 15 studies were selected. Finally, after rating the methodological quality of the studies, the sample consisted of 14 primary studies that met the inclusion and methodological quality criteria.

Description of the Studies

The main characteristics of the 14 studies are shown in Table 2. All of them used a cross-sectional design and non-probabilistic sampling methods, and they were carried out in the USA.

Meta-Analysis on the Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence

The forest plots from 1 to 5 show the prevalence of victimization for each primary study, together with its confidence interval and the weighting based on the methodological quality of the prevalence data.

Intimate Partner Violence Victimization

Forest plots 1 and 2 show intimate partner violence victimization evaluated by an original instrument. The results reveal a mean prevalence of 0.48 (95 % CI, 0.44–0.52) of intimate partner violence victimization over the lifespan, based on a meta-analysis of four studies (see Fig. 2), and a mean prevalence of 0.15 (95 % CI, 0.05–0.30) in the current/most recent relationship, based on a meta-analysis of three studies (see Fig. 3). The studies present low heterogeneity in the meta-analysis on intimate partner violence over the lifespan (Q = 4.37, p = 0.22, I 2 = 31 %). The heterogeneity of the studies is high in the meta-analysis on intimate partner violence in the current/most recent relationship (Q = 4.37, p = 0.22, I 2 = 31 %; Q = 33.30, p < 0.001, I 2 = 94 %, respectively).

It can be observed that the mean prevalence is higher for victimization over the lifespan (48 %) than for victimization in the current relationship (15 %). There is no overlap between the confidence intervals; therefore, the difference between the prevalence rates is statistically significant.

Victimization in Different Forms of Intimate Partner Violence

Forest plots 3, 4, and 5 show the mean prevalence for victimization in different forms of violence (physical, sexual, and psychological/emotional violence) over the lifespan (Figs. 4, 5, and 6). Moreover, the prevalence was evaluated with the author’s own instrument. The results show a mean prevalence in physical violence of 0.18 (95 % CI, 0.0–0.48), in sexual violence of 0.14 (95 % CI, 0.0–0.37), and in psychological/emotional violence of 0.43 (95 % CI, 0.14–0.73).

In the three meta-analytic studies, the heterogeneity of the primary studies is high (Q = 482.70, p < 0.001, I 2 = 100 %; Q = 492.41, p < 0.001, I 2 = 99 %; Q = 446.82, p < 0.001, I 2 = 100 %, respectively).

It can be observed that the mean prevalence is higher for psychological/emotional violence (43 %) than for physical (18 %) and sexual (14 %) violence. Moreover, the mean prevalence of physical violence (18 %) is greater than the mean prevalence of sexual violence (14 %).

The mean prevalence of victimization in the different forms of intimate partner violence in the current or most recent relationship was calculated through meta-analyses based on two studies each. The mean prevalence of physical violence measured with a standardized instrument is 0.16 (95 % CI, 0.13–0.19), and 0.10 (95 % CI, 0.07–0.14) when the physical violence is measured with an original instrument. In these two meta-analytic studies, the studies do not present heterogeneity (Q = 0.98, p = 0.32, I 2 = 0 % and Q = 0.86, p = 0.35, I 2 = 0 %, respectively). The mean prevalence of sexual violence evaluated with an original instrument is 0.04 (95 % CI, 0.00–0,13), and for psychological violence, 0.11 (95 % CI, 0.03–0.21). In these two meta-analytic studies, the studies do not present heterogeneity (Q = 8.34, p < 0.001, I 2 = 88 % and Q = 7.12, p = 0.01, I 2 = 86 %, respectively).

Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration

On intimate partner violence perpetration over the lifespan, evaluated by the author’s own instrument, the results of the meta-analysis based on two studies show a mean prevalence of 0.43 (95 % CI, 0.15–0.74), with high heterogeneity between the studies (Q = 8.26, p < 0.001, I 2 = 99 %).

Perpetration of Different Forms of Intimate Partner Violence

Regarding the perpetration over the lifespan of different forms of intimate partner violence, evaluated through an original instrument, the results, based on different meta-analyses of two studies each, show a mean prevalence of physical violence perpetration in the couple of 0.12 (95 % CI, 0.00–0.36), of sexual violence of 0.07 (95 % CI, 0.0–0.30), and of psychological/emotional violence of 0. 27 (95 % CI, 0.02–0.63). In the three meta-analyses, the heterogeneity of the studies is high (Q = 0.88, p < 0,001, I 2 = 99 %; Q = 153.56, p < 0,001, I 2 = 99 %; and Q = 146.35, p < 0.001, I 2 = 99 %, respectively).

Discussion

This study represents the first systematic meta-analytic quantitative review carried out on the prevalence of intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbian couples. The results show a mean prevalence of intimate partner violence victimization over the lifespan of 48 % (95 % CI, 44–52 %) and perpetration of 43 % (95 % CI, 15–74 %), and a mean prevalence of victimization in the current relationship of 15 % (95 % CI, 5–30 %). In this sense, the findings show that the rates of victimization in intimate partner violence over the lifespan are greater than in the current or most recent relationship, as occurs in heterosexual intimate partner relationships, as would be expected (García-Moreno et al. 2005).

Psychological/emotional violence is the most prevalent form of abuse in self-identified lesbian women. It includes behaviors such as name-calling; criticizing; humiliation; sulking/ignoring; threatening to leave the relationship; yelling; false accusations (Lie et al. 1991); treating the partner like a servant; making important decisions without discussing them; using age/race/class/religion/sexual orientation against the partner; blaming the partner for problems with alcohol/drugs, abusive childhood, suicidal/self-abusive behavior, and the problems in the relationship; and controlling what the partner does, who she sees, or who she talks to (Turell 2000). In another study, the participants have to define for themselves what psychological/emotional abuse means (Lie and Gentlewarrier 1991).

Throughout life, psychological/emotional violence is experienced by 43 % (95 % CI, 14–73 %) of self-identified lesbian women and perpetrated by 27 % (95 % CI, 2–63 %), and in the current or most recent relationship, psychological/emotional violence is experienced by 11 % of self-identified lesbian women. These data are in line with previous studies on intimate partner violence between lesbian women and women with a prior history of same-sex partners. These studies point out that psychological/emotional violence is the most prevalent form of abuse in sexual-affective relationships between women (Lewis et al. 2012; Matte and Lafontaine 2011; McClennen et al. 2002; Messinger 2011; Renzetti 1988).

In general terms, the high rates of intimate partner violence suggest the need to develop and implement programs for violence prevention in same-sex couples. The scientific literature shows that battering in heterosexual couples and in same-sex couples shares forms of intimate partner violence and different correlates, such as substance abuse and violence in the family background (McClennen 2005; Murray et al. 2007; Peterman and Dixon 2003; West 2002). However, the abuse in same-sex couples has some peculiarities that require differential treatment (Brown 2008). Some examples that can be highlighted are homophobic control (or psychological tactics used to exert control and power over the partner) as a specific form of violence in same-sex couples, and as specific correlates of it, the stress of belonging to a sexual minority and the fusion in the case of female couples. All of this is a manifestation of the homophobic social context in which same-sex partner violence occurs (Bunker 2006; Burke and Owen 2006; Elliott 1996; Gumienny 2010; Hammond 1989; McClennen 2005; Peterman and Dixon 2003; Renzetti 1992; Ristock 1991; Tigert 2001; West 2002). Examples of homophobic control behaviors, evaluated in four of the 14 studies analyzed, are threatening the partner with revealing his/her sexual orientation to family, friends, employers, and other significant people (Balsam and Szymanski 2005; Eaton et al. 2008; Scherzer 1998; Turell 2000); reinforcing internalized homophobia by telling the partner that he/she deserves the abuse due to being a lesbian; questioning whether the partner is a “real” lesbian; and forcing the partner to show physical and sexual affection in public (Balsam and Szymanski 2005).

Therefore, intimate partner violence prevention programs must take into account the specific characteristics of abuse in lesbian and gay men couples (Brown 2008). As Pharr (1988) points out, there is a huge difference between a battered lesbian and a battered non-lesbian: the experience of lesbian violence develops within a misogynous and homophobic world, while the experience of the abused non-lesbian develops in a misogynous world.

This contextual difference is fundamental in the genesis of intimate partner violence between lesbian couples and gay men couples (Balsam 2001; Tigert 2001). Therefore, it is necessary to develop and implement homophobia prevention programs, both to combat intimate partner violence and to combat other forms of violence (e.g., hate crimes) and the discrimination that is rooted in homophobic beliefs (Herek 2004, 2009; Pelullo et al. 2013; Stotzer 2010). Moreover, this homophobic context also plays an important role in maintaining partner violence in same-sex couples. On the one hand, the fear of rejection and discrimination associated with the sexual orientation makes it difficult for victims of same-sex partner violence to seek help from service providers (Ard and Makadon 2011; Brown 2008). The study by St. Pierre and Senn (2010) with a sample of gays and lesbians analyzed the external barriers to seeking help (availability of services for same-sex couples, the sensitivity of these services, past experiences of discrimination due to sexual orientation, and outness). The results showed that only the degree of outing predicted help-seeking. On the other hand, the LGBT community itself, due to the fear of suffering greater stigma, can maintain the invisibility of the situations of partner violence that occur in the community.

Therefore, there is a need for education and training programs in same-sex couple partner violence for service providers not specifically serving LGBT people (e.g., health care, social services, criminal justice professionals, etc.), in order to guarantee that LGBT people who are victims of partner violence are well received by them, thus avoiding any possible secondary victimization (e.g., denying the violence based on the myth that same-sex relationships are egalitarian), ensure that a good screening and assessment of the situation of partner violence is performed, and, finally, make sure the victim’s needs are met (Ard and Makadon 2011; Brown 2008; Hart and Klein 2013; Hassouneh and Glass 2008; NCAVP 2013; St. Pierre and Senn 2010). There is also a need for education and training programs and campaigns directed toward the community in general and the LGBT community itself, in order to increase the knowledge about same-sex couple abuse. This would make it possible to break down stereotypes associated with partner violence (e.g., the man as the abuser and the woman as the victim of the abuse) that keep maltreated lesbian women from being recognized as abuse victims, identify cases of partner violence, and empathize with abuse victims (Hassouneh and Glass 2008). Furthermore, these information campaigns would also allow abused lesbian women to have information about the available service providers in situations of partner abuse, which would facilitate help-seeking in these situations.

These prevention and treatment programs require changes in public and social policies. For example, public institutions would have to dedicate public funds to underwriting the costs stemming from the development and implementation of education and training programs and campaigns on same-sex partner violence, methodologically high-quality research designed to study partner violence in the LGBT population and discover its prevalence and the social and personal correlates associated with it (e.g., with representative samples of the LGBT population), increase the availability of specific social services for same-sex partner violence, or create accessible services.

Another important change in the policies for the prevention of partner violence in same-sex couples would require the legislature to modify the laws on partner violence to include partner violence in same-sex couples, so that the abused person can access the necessary social resources (e.g., safe houses, economic help if the victim depends economically on the aggressor), protective measures, etc.. Furthermore, public authorities should prohibit all acts of discrimination due to sexual orientation by service providers (NCAVP 2013). Moreover, it is necessary to revise and update interventions with perpetrators of same-sex partner violence to make them more specific and effective (Hart and Klein 2013).

Limitations of the Present Systematic Review

One of the main limitations of our study is related to the small number of studies that have been included in the different meta-analytic studies. The low number of studies could affect the precision of the estimation of variance between the studies. Especially important is the careful interpretation of the mean prevalence rates when computed with two studies, given the limited precision of the estimations. However, it should be taken into account that the studies selected met the inclusion criteria and had an adequate level of methodological quality. The rigorous selection of the primary studies was intended to assure the quality of the evidence they provided. Therefore, it was considered more important to summarize the evidence using studies with high methodological quality than to review a larger number of studies with poor-quality research designs. One conclusion derived from this situation is that there are few studies with sufficient methodological quality published on intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbian couples.

Moreover, meta-analytic reviews are often carried out with a small number of primary studies (Higgins et al. 2002; Cochran 1954; Sterne and Egger 2001). A study elaborated by the Cochrane Collaboration with 509 meta-analytic studies points out that approximately a quarter of the meta-analyses have an I 2 value of around 50 % (Higgins et al. 2002). The heterogeneity in the mean prevalence values detected in our study indicates the presence of differences in the prevalence results of the primary studies. Given the small sample size of the studies analyzed, it was not possible to perform analyses by moderator variables to study any possible theoretical explanations for the presence of the heterogeneity in greater detail. However, the heterogeneous nature of this type of studies should be kept in mind and, therefore, the need to summarize the mean prevalence of lesbian intimate partner violence in a quantitative and weighted manner.

Our study represents the first systematic meta-analytic review on the prevalence of intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbian women. In this sense, this study allows a more accurate view of the prevalence of this phenomenon, with the limitations mentioned above. Furthermore, our study shows the limited number of research studies on intimate partner violence in lesbian couples that meet the inclusion and methodological quality criteria established in the protocol for this systematic meta-analytic quantitative review. It also shows that all of the studies included in this systematic review were carried out in the USA. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the prevalence of intimate partner violence in lesbian couples and same-sex couples in other societies and cultures, using research designs with adequate methodological quality (e.g., In Spain, only one reference was found for same-sex intimate partner violence in the theoretical study by Cantera (2004)). The use of convenience samples or volunteers is also a question that should be addressed in the planning stage of studies in order to apply techniques of random sampling. However, the application of these random sampling techniques is quite difficult, as the identification of the population of LGBT people is required.

Recommendations

Future studies on the prevalence of violence in lesbian couples should evaluate the sexual orientation of the participants and the sex of the perpetrator of the violence, or whether the violence occurred in an intimate relationship between people of the same sex (Burke and Follingstad 1999; Murray and Mobley 2009). Furthermore, it would be advisable to analyze the rates of violence in bisexual women couples and lesbian women couples in separate groups (Gumienny 2010).

In addition, research on the prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence should use the same definitions of partner violence and forms of violence, such as, for example, the definitions proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999) or the World Health Organization (2010, 2012), and they should report on the same periods recalled (e.g., over the lifespan, the past year). This would help to integrate the results in later meta-analytic studies and elaborate more homogeneous studies. Thus, the studies within each category could be more homogeneous, increasing the validity of the results of meta-analytic reviews.

Finally, as suggested in previous literature reviews on the topic of same-sex intimate partner violence (Burke and Follingstad 1999; Murray and Mobley 2009), future studies on intimate partner violence in lesbian women should use standardized measurement instruments with good psychometric properties; make sure that members of the same intimate relationship are not both included in the sample or, if they are, match them in the data analysis to control any possible overlap between their data; and use standardized participant conditions for all participants.

References

An asterisk has been placed next to those references that are included in the systematic review.

Ard, K. L., & Makadon, H. J. (2011). Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 930–933. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1697-6.

Baker, N. L., Buik, J. D., Kim, S. E., Moniz, S., & Nava, K. L. (2013). Lessons from examining same-sex intimate partner violence. Sex Roles, 69, 182–192. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0218-3.

Balsam, K. F. (2001). Nowhere to hide: lesbian battering, homophobia and minority stress. Women & Therapy, 23, 25–37.

*Balsam, K. F., Rothblum, E. D., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2005). Victimization over the life, span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 477–487.

*Balsam, K. F., & Szymanski, D. M. (2005). Relationship quality and domestic violence in women′s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 258–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00220.x.

Barendregt, J. J., Doi, S. A., Lee, Y. Y., Norman, R. E., & Vos, T. (2013). Meta-analysis of prevalence. Epidemiology Community and Health, 67, 974–978. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203104.

Barrett, B. J., & St. Pierre, M. (2013). Intimate partner violence reported by lesbian-, gay-, and bisexual-identified individuals living in Canada: An exploration of within-group variations. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 25, 1–23. doi:10.1080/10538720.2013.751887.

Brand, P. A., & Kidd, A. H. (1986). Frequency of physical aggression in heterosexual and female homosexual dyads. Psychological Reports, 59, 1307–1313.

Brockwell, S. E., & Gordon, I. R. (2011). A comparison of statistical methods for meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 20, 825–840.

Brown, C. (2008). Gender-role implications on same-sex intimate partner abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 457–462. doi:10.1007/s10896-008-9172-9.

Bunker, J. (2006). Domestic violence in same-gender relationships. Family Court Review, 44, 287–299.

Burke, T. W., Jordan, M. L., & Owen, S. S. (2002). A cross-national comparison of gay and lesbian domestic violence. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 18, 231–257. doi:10.1177/1043986202018003003.

Burke, L. K., & Follingstad, D. R. (1999). Violence in lesbian and gay relationships: theory, prevalence, and correlational factors. Clinical Pshycjhology Review, 19, 487–512. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00054-3.

Burke, T. W., & Owen, S. S. (2006). Same-sex domestic violence: is anyone listening? The Gay & Lesbian Review, 8(1), 6–7.

Cantera, L. (2004). Cuestiones en busca de paradigma. En L. Cantera. Más allá del género. Nuevos enfoques de nuevas dimensiones de la violencia en la pareja. [Questions in search of a paradigm. In L. Cantera. Beyond gender. New approaches on new dimensions of intimate partner violence.] Tesis Doctoral. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Carvalho, A. M., Lewis, R. J., Derlega, V. J., Winstead, B. A., & Viggiano, C. (2011). Internalized sexual minority stressors and same-sex intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 26, 501–509. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9384-2.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/ipv_surveillance/Intimate%20Partner%20Violence.pdf.

Chong, E. S. K., Mak, W. W. S., & Kwong, M. M. F. (2013). Risk and protective factors of same-sex intimate partner violence in Hong Kong. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 1476–1497. doi:10.1177/0886260512468229.

Cochran, W. G. (1954). The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics, 10, 101–129.

DiStefano, A. S. (2009). Intimate partner violence among sexual minorities in Japan: exploring perceptions and experiences. Journal of Homosexuality, 56, 121–146. doi:10.1080/00918360802623123.

Doi, S. A., & Thalib, L. (2008). A quality-effects model for meta-analysis. Epidemiology, 19, 94–100.

*Eaton, L., Kaufman, M., Fuhrel, A., Cain, D., Cherry, C., Pope, H., & Kalichman, S. C. (2008). Examining factors co-existing with interpersonal violence in lesbian relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 697–705. doi 10.1007/s10896-008-9194-3.

Elliott, P. (1996). Shattering illusions: same-sex domestic violence. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 4, 1–8.

Frankland, A., & Brown, J. (2014). Coercive control in same-sex intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 15–22. doi:10.1007/s10896-013-9558-1.

García-Moreno C., Jansen H.A.F.M., Ellsberg M., Heise L., & Watts C. (2005) Multi-country study from the WHO on women′s health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health-related events and women′s responses to this violence. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/en/.

Goldberg, N., & Meyer, I. (2013). Sexual orientation disparities in history of intimate partner violence: results from the California health interview survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 1109–1118. doi:10.1177/0886260512459384.

Gumienny, L. A. (2010). Predictors of intimate partner violence in women′s sexual minority relationship. Proquest Dissertations and Theses: PsycInfo.

Hammond, N. (1989). Lesbian victims of relationship violence. Women & Therapy, 8, 89–105.

Hardesty, J. L., Oswald, R. F., Khaw, L., & Fonseca, C. (2011). Lesbian/bisexual mothers and intimate partner violence: help seeking in the context of social and legal vulnerability. Violence Against Women, 17, 28–46. doi:10.1177/1077801209347636.

Hart, B. J., & Klein, A. R. (2013). Practical implications of current intimate partner violence research for victim advocates and service providers. NCJRS Library collection: US Department of Justice: available online at https://ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=266429.

Hassouneh, D., & Glass, N. (2008). The influence of gender role stereotyping on women′s experiences of female same-sex intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 14, 310–325. doi:10.1177/1077801207313734.

Hedges, L. V. (1994). Fixed effects models. In H. Cooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 285–299). New York: Sage.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press.

Heneghan, A. M., Horwitz, S. M., & Leventhal, J. M. (1996). Evaluating intensive family preservation programs: a methodological review. Pediatrics, 97, 535–542.

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 1, 6–24. doi:10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6.

Herek, G. M. (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 54–74. doi:10.1177/0886260508316477.

Higgins, J. P. T., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21, 1539–1558.

Higgins, J., Thompson, S., Deeks, J., & Altman, D. (2002). Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. Journal Health Service Research Policy, 7, 51–61.

Huedo-Medina, T. B., Sanchez-Meca, J., Marin-Martinez, F., & Botella, J. (2006). Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychological Methods, 11, 193–206.

Island, D., & Letellier, P. (1991). Men who beat the men who love them: battered gay men and domestic violence. Binghamton: Haworth Press.

Kalichman, S., & Rompa, D. (1995). Sexually coerced and noncoerced gay and bisexual men: factors relevant to risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Journal of Sex Research, 32, 45–50.

Lewis, R. J., Milletich, R. J., Kelley, M. L., & Woody, A. (2012). Minority stress, substance use, and intimate partner violence among sexual minority women. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 247–256. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.004.

*Lie, G., & Gentlewarrier, S. (1991) Intimate violence in lesbian relationships: discussion of survey findings and practice implications. Journal of Social Services Research, 15, 41–59. doi:10.1300/J079v15n01_03.

*Lie, G., Schilit, R., Bush, J., Montagne, M., & Reyes, L. (1991) Lesbians in currently aggressive relationships: How frequently do they report aggressive past relationships? Violence and Victims, 6, 121–135.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lobel, K. (Ed.). (1986). Naming the violence: speaking out about lesbian battering. Seattle: Seal Press.

Lockhart, L. L., White, B. W., Causby, V., & Isaac, A. (1994). Letting out the secret: violence in lesbian relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9, 469–492. doi:10.1177/088626094009004003.

Matte, M., & Lafontaine, M. (2011). Validation of a measure of psychological aggression in same-sex couples: descriptive data on perpetration and victimization and their association with physical violence. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7, 226–244. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2011.56494.

McClennen, J. C. (2005). Domestic violence between same-gender partners: recent findings and future research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 149–154.

McClennen, J. C., Summers, A. B., & Daley, J. G. (2002). The lesbian partner abuse scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 12, 277–292. doi:10.1177/0886260504268762.

Messinger, A. M. (2011). Invisible victims: same-sex IPV in the National Violence Against Women Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 2228–2243. doi:10.1177/0886260510383023.

*Miller, D. H., Greene, K., Causby, V., White, B. W., & Lockhart, L. L. (2001) Domestic violence in lesbian relationships. Women & Therapy, 3, 107–127. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003.

Monterde-i-Bort, H., Pascual-Llobell, J., & Frias-Navarro, D. (2006). Errores de interpretación de los métodos estadísticos (Interpretation mistakes in statistical methods: their importance and some recommendations). Psicothema, 18, 848–856.

Moradi, B., Mohr, J. J., Worthington, R. L., & Fassinger, R. E. (2009). Counseling psychology research on sexual (orientation) minority issues: conceptual and methodological challenges and opportunities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 5–22. doi:10.1037/a0014572.

Murray, C. E., & Graybeal, J. D. (2007). Methodological review of intimate partner violence prevention research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 1250–1269.

Murray, C. E., & Mobley, K. A. (2009). Empirical research about same-sex intimate partner violence: a methodological review. Journal of Homosexuality, 56, 361–368. doi:10.1080/00918360902728848.

Murray, C. E., Mobley, A. K., Buford, A. P., & Seaman-DeJohn, M. M. (2007). Same-sex intimate partner violence: dynamics, social context, and counseling implications. The Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 1(4), 7–30.

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (2013). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and HIV-affected intimate partner violence 2012. New York, NY: New York City Anti-Violence Project, 2011, available online at http://www.avp.org/documents/IPVReportfull-web_000.pdf.

Pelullo, C. P., Di Giuseppe, G., & Angelillo, I. F. (2013). Frequency of discrimination, harassment, and violence in lesbian, gay men, and bisexual in Italy. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e74446. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074446.

Peterman, L. M., & Dixon, C. G. (2003). Domestic violence between same-sex partners: implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81, 40–47.

Pharr, S. (1988). Homophobia: A weapon of sexism. Little Rock: Chardon Press.

Renzetti, C. M. (1988). Violence in lesbian relationship: a preliminary analysis of causal factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 3, 381–399.

Renzetti, M. C. (1992). Violent betrayal: partner abuse in lesbian relationship. Newbury Park: Sage.

Reyes-Mena, F., Rodríguez, J. R., & Malavé, S. (2005). Manifestaciones de la Violencia Doméstica en una Muestra de Hombres Homosexuales y Mujeres Lesbianas Puertorriqueñas. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 39, 449–456.

Ristock, J. L. (1991). Beyond ideologies: understanding violence in lesbian relationships. Canadian Woman Studies, 12, 74–79.

Roberts, A., Austin, B., Corliss, H., Vandermorris, A., & Koenen, K. (2010). Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 2433–2441.

*Rose, S. M. (2003) Community interventions concerning homophobic violence and partner violence against lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7, 125–139. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_08.

*Scherzer, T. (1998) Domestic violence in lesbian relationships: findings of the lesbian relationships research project. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 2, 29–47. doi: 10.1300/J155v02n01_03.

*Schilit, R., Lie, G., & Montagne, M. (1990) Substance use as a correlate of violence in intimate lesbian relationships. Journal of Homosexuality, 19, 51–65, doi: 10.1300/J082v19n03_03.

*Schilit, R., Lie, G., Bush., J., Montagne, M., & Reyes, L. (1991). Intergenerational transmission of violence in lesbian relationships. Affilia, 6, 172–182. doi: 10.1177/088610999100600105.

Sterne, J. A. C., & Egger, M. (2001). Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, 1046–1055.

St. Pierre, M., & Senn, C. Y. (2010). External barriers to help-seeking encountered by Canadian gay and lesbian victims of intimate partner abuse: an application of the Barriers model. Violence and Victims, 25, 536–552. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.536.

Stotzer, R. L. (2010). Sexual orientation-based hate crimes on campus: the impact of policy on reporting rates. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 7, 147–154. doi:10.1007/s13178-010-0014-1.

*Telesco, G. A. (2003). Sex role identity and jealously as correlates of abusive behavior in lesbian relationships. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 8, 153–169. doi: 10.1300/J137v08n02_10.

Tigert, L. M. (2001). The power of shame: lesbian battering as manifestation of homophobia. Women & Therapy, 23, 73–85.

*Turell, S. C. (2000). A descriptive analysis of same-sex relationship violence for a diverse sample. Journal of Family Violence, 15, 281–293.

*Waldner-Haugrud, L. K., Vaden, L., & Magruder, B. (1997). Victimization and perpetration rates of violence in gay and lesbian relationships: gender issues explored. Violence and Victims, 12, 173–184.

*Waldner-Haugrud, L. K., & Vaden, L. (1997). Sexual coercion in gay/lesbian relationships: descriptives and gender differences. Violence and Victims, 12, 87–98.

Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Breiding, M. J. (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf

West, C. M. (2012). Partner abuse in ethnic minority and gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender populations. Partner Abuse, 3, 336–357.

West, C. M. (2002). Lesbian intimate partner violence: prevalence and dynamics. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 6, 121–127. doi:10.1300/J155v06n01_11.

World Health Organization (2010). Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564007_eng.pdf.

World Health Organization (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf.

Acknowledgments

This study was possible due to the economic support of the VALi+d program for pre-doctoral Training of Research Personnel (ACIF/2013/167), Conselleria d′Educació, Cultura i Sport, Generalitat Valenciana (Spain).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Badenes-Ribera, L., Frias-Navarro, D., Bonilla-Campos, A. et al. Intimate Partner Violence in Self-identified Lesbians: a Meta-analysis of its Prevalence. Sex Res Soc Policy 12, 47–59 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-014-0164-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-014-0164-7