Abstract

The medical community’s efforts to address intimate partner violence (IPV) have often neglected members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) population. Heterosexual women are primarily targeted for IPV screening and intervention despite the similar prevalence of IPV in LGBT individuals and its detrimental health effects. Here, we highlight the burden of IPV in LGBT relationships, discuss how LGBT and heterosexual IPV differ, and outline steps clinicians can take to address IPV in their LGBT patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The medical community has responded to the public health problem of intimate partner violence (IPV)1 with a range of efforts, from screening reminders in the electronic medical records of female patients to hospital-based IPV programs. While such efforts are necessary and important, they are notable for whom they exclude. Indeed, male victims of IPV have received little attention in the health care field2. Beyond men as a whole, however, the medical community’s efforts have largely neglected members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) population, compounding the health disparities already faced by these groups3. This commentary seeks to highlight the prevalence and characteristics of IPV within LGBT relationships and share perspectives on how clinicians can respond to this important and often hidden problem.

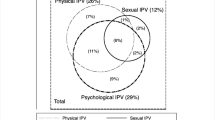

Although the LGBT population is heterogeneous, encompassing a wide range of behaviors and identities, many groups within this population experience IPV at least as frequently as heterosexual women, the focus of most organized screening and intervention efforts. The National Violence Against Women (NVAW) survey found that 21.5% of men and 35.4% of women reporting a history of cohabitation with a same-sex partner had experienced physical abuse in their lifetimes; the corresponding rates for men and women with a history of only opposite-sex cohabitation were 7.1% and 20.4%, respectively4. Although this study did not directly assess sexual orientation, other research explicitly doing so has uncovered similarly high rates of IPV. One survey of 3,000 gay men found 5-year rates of physical and sexual abuse of 22.0% and 5.1%, respectively5. While cross-study comparisons are problematic, these 5-year rates are similar to the lifetime rates of 20.4% for physical assault and 4.4% for sexual assault for opposite-sex cohabitating women in the NVAW survey4. Other groups, particularly transgender individuals—those whose gender identity is not concordant with their birth sex or who defy conventional gender classification6—may suffer from an even greater burden of IPV. Transgender respondents reported lifetime physical abuse rates by a partner of 34.6%, versus 14.0% for gay or lesbian individuals, in a survey of 1,600 people in Massachusetts7. The finding of high rates of IPV among transgender individuals, as well as men and women in same-sex relationships, defies the conventional notion that such violence solely afflicts heterosexual women.

Many aspects of domestic violence in LGBT groups, such as the role of power dynamics, the cyclical nature of abuse, and the escalation of abuse over time, are similar between LGBT and heterosexual relationships8,9. However, there are some aspects of IPV that are unique to the LGBT experience. In particular, outing may constitute both a tool of abuse and a barrier to seeking help. LGBT individuals often hide outward expression of their sexual orientation or gender identity for fear of stigma and discrimination; abusive partners may exploit this fear through the threat of forced outing9. Even if batterers do not employ outing as an abuse tactic, victims’ reluctance to out themselves may hinder them from turning to family, friends, or the police for support, further isolating them in abusive relationships9. Although not entirely unique to the LGBT experience, another salient aspect of domestic abuse in the LGBT community is the background of stigma and discrimination upon which it occurs. Many LGBT individuals have experienced prior psychological or physical trauma, whether in the form of rejection by their families of origin, hate speech or hate crimes in their communities, or bullying at school10–12; these experiences are particularly common among transgender individuals11,13,14. The recent suicides of four teenagers, all of whom were reportedly bullied because of their sexual orientation, serve as a chilling reminder of the impact such trauma can have15. Prior experiences of violence and discrimination, coupled with the failure of the community to adequately respond, may make LGBT victims less likely to seek help when they experience IPV.

When LGBT individuals do attempt to access IPV services, however, their options are often severely limited. LGBT shelter services are rare to non-existent in many regions16. Men may not be admitted to shelters regardless of their status as victims, and transgender women—individuals born male but identifying as female—may not gain access to women’s shelters16,17. Curt Rogers, founder and director of an IPV program for gay men in Massachusetts, adds that “although attitudes are slowly shifting, the overwhelming majority of domestic violence programs view domestic violence as a male-perpetrated, heterosexual experience. As such, when services are provided to LGBT victims, the lack of cultural competency and informed support can re-traumatize the victim, leading the individual to return to their partner or stop seeking support.”

Perhaps because of the multiple barriers that confront LGBT abuse victims and the invisibility of the problem in the context of IPV services, the role of the victim’s health care provider as caretaker and advocate is all the more critical. Clinicians can take multiple steps, from the examination room to the classroom, to help address this problem (Table 1).

First, as with any patient affected by IPV, the initial step is to recognize the problem, offer empathic support, and help ensure safety. Although the universal screening of asymptomatic individuals, including women, is controversial, providers must be alert to the possibility of IPV as a cause of distress and illness among their LGBT patients. There are few data on particular clinical features that herald IPV in LGBT individuals, but a lower threshold for screening transgender patients may be warranted, as they appear to experience higher rates of violence than other members of the LGBT community. Assessing for abuse in LGBT patients is rendered problematic, however, by the rarity with which providers inquire—and patients reveal—sexual orientation and gender identity18,19. Disclosing IPV in an LGBT relationship entails discussing one’s identity, which some patients may find difficult without prior assurance of providers’ non-judgmental attitudes.

Thus, first inquiring about sexual orientation and gender identity in a sensitive and open manner, rather than simply screening for IPV without such a discussion beforehand, may be critical to increasing the identification of abuse among LGBT patients. Clinicians can signal their willingness to discuss non-heterosexual relationships by using inclusive language both in the examination room and on intake forms and signs in the waiting area; such language has been associated with increased disclosure of sexual orientation18. For instance, instead of asking patients about their wives or husbands, providers should inquire about spouses or partners. During the sexual history, the question “Do you have sex with men, women, or both men and women?” likewise indicates a non-judgmental attitude20. In some cases, such behaviorally based questions may be preferable to those focused on a patient’s identity as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. This may be particularly important for adolescent patients still exploring their sexuality as well as for non-white men who have sex with men, who are much less likely than their white counterparts to self-identify as gay19,21,22. More important than the specific terminology used, however, is that providers convey an attitude of empathy, curiosity, and respect23. In addition to facilitating discussions of IPV, candidly discussing sexual behavior and gender identity allows providers to address other health issues pertinent to LGBT patients.

Second, by asking LGBT individuals about IPV and identifying it as such when it occurs, providers can fulfill an important educational role for their LGBT patients. Abuse in the LGBT population has not only been invisible in the health care field; the subject has historically been unacknowledged in the LGBT community, too, perhaps because of fear of increasing the stigma of LGBT relationships8,9. Such silence has contributed to a dearth of information about IPV among victims, with detrimental effects. Half of battered gay men in one study cited a lack of knowledge about domestic violence as a major reason for remaining in abusive relationships24. By correcting the myth that battering does not occur in LGBT partnerships, providers may help empower affected patients to seek safety and assistance.

Third, providers must be informed about, and be prepared to address, the health risks associated with IPV in LGBT patients. Gay and bisexual men who experience domestic violence are more likely to abuse alcohol and other substances and engage in unsafe sexual behaviors, such as unprotected anal intercourse25. A disclosure of abuse from men in same-sex relationships may thus necessitate a sensitive evaluation for substance abuse, HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections. In addition, as for all victims of IPV, clinicians must assess for injuries due to abuse, documenting their findings in the medical record as clearly and objectively as possible. Although some states exclude LGBT individuals from domestic violence laws16, clear and complete documentation of injuries in the medical record may be helpful to those patients who are able to pursue legal action against their batterers.

Fourth, in order to provide well-informed referrals, clinicians should familiarize themselves with the resources available at their institutions and within their communities for LGBT victims of IPV. While many emergency departments, hospitals, and clinics have IPV advocacy programs, such programs have historically failed to respond adequately to abuse in LGBT groups26. Providers should routinely inquire about the availability of resources, such as information, counseling, and shelter services, that are sensitive to LGBT individuals. If resources are found to be lacking, providers can act as advocates for improved services. Such efforts can range from revising domestic violence posters and pamphlets to feature more inclusive language, to updating screening reminders in the electronic medical record, to advocating for shelter space for LGBT abuse victims.

Fifth, those providers involved in developing clinical resources and practice guidelines surrounding IPV should revise their materials to reflect the burden of violence in the LGBT community. Currently, IPV among LGBT individuals receives little attention in the resources to which clinicians frequently turn for information. For instance, the article on IPV in UpToDate, a popular online reference for providers, contains only one sentence on abuse in LGBT relationships27. Likewise, multiple professional bodies, including the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recommend screening women for IPV or considering it as a cause of illness in various settings28; however, none specifically mention gay, bisexual, or transgender individuals. In addition to revising clinical resources and guidelines to be more inclusive, those involved in medical education on domestic violence should ensure that their curricula acknowledge this important problem. We have found testimony by a trained survivor of same-sex IPV to be a powerful educational and advocacy tool, and incorporating such a presentation into a domestic violence curriculum may provide an eye-opening experience for medical trainees. Finally, for those involved in research on IPV, explicit inclusion of LGBT individuals in studies on abuse can help rectify the critical need for more research on this topic.

The 2000 United States census identified nearly 600,000 households headed by same-sex couples, spread across 99 percent of the nation’s counties29. These data underestimate the size of the LGBT population, as they were voluntarily collected and did not include single gay or lesbian and transgender individuals; nevertheless, they demonstrate that the LGBT population is widespread. Since IPV is at least as common in LGBT groups as in the general population, any medical provider may be called upon to address IPV in LGBT patients, regardless of where he or she practices. Office practices, clinical resources, practice guidelines, medical curricula, and research agendas should be amended to reflect this. Highlighting IPV in the LGBT community is not intended to distract from the pressing public health problem of violence against heterosexual women. Rather, by focusing on violence in LGBT groups in addition to that experienced by heterosexual individuals, clinicians can promote equity in health care and help ensure that all their patients lead safe and healthy lives.

References

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO Multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9.

Kimberg LS. Addressing intimate partner violence with male patients: a review and introduction of pilot guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2071–8.

Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Healthy People 2010 Companion Document for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Health. San Francisco, CA: Gay and Lesbian Medical Association; 2001. Available at: http://www.glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/HealthyCompanionDoc3.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2011.

Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2000. P. 29–31. Report No.: NCJ 181867.

Greenwood GL, Relf MV, Huang B, Pollack LM, Canchola JA, Catania JA. Battering victimization among a probability-based sample of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1964–9.

Goldberg J, Matte N, MacMillan M, Hudspith M. Community survey: transition/crossdressing services in BC. Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, 2003. Available at http://transhealth.vch.ca/resources/library/thpdocs/0301surveyreport.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2011.

Landers S, Gilsanz P. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Massachusetts. Massachusetts Department of Public Health; 2009. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/Eeohhs2/docs/dph/commissioner/lgbt_health_report.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2011.

McClennen J. Domestic violence between same-gender partners: recent findings and future research. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20:149–54.

Kulkin HS, Williams J, Borne HF, de la Bretonne D, Laurendine J. A review of research on violence in same-gender couples: a resource for clinicians. J Homosex. 2007;53:71–87.

Robin L, Brener ND, Donahue SF, Hack T, Hale K, Goodenow C. Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex sexual partners in representative samples of Vermont and Massachusetts high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:349–55.

Clermont KJ. Lesbians and same-sex relationships. In: Liebschutz JM, Frayne SM, Saxe GN, eds. Violence against women: A physician’s guide to identification and management. Philadelphia: ACP; 2003:237–50.

Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:477–87.

Kenagy GP. Transgender health: findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health Soc Work. 2005;30:19–26.

Factor RJ, Rothblum ED. A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3:11–30.

McKinley J. Suicides put light on pressures of gay teenagers. New York Times. 2010 Oct 3. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/04/us/04suicide.html?ref=tylerclementi. Accessed March 6, 2011.

Pattavina A, Hirschel D, Buzawa E, Faggiani D, Bentley H. A comparison of the police-response to heterosexual versus same-sex intimate partner violence. Violence against Women. 2007;13:374–94.

Hines DA, Douglas EM. The reported availability of U.S. domestic violence services to victims who vary by age, sexual orientation, and gender. Partner Abuse. 2011;2:3–30.

Eliason MJ, Schope R. Does “don’t ask don’t tell” apply to health care? Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people’s disclosure to health care providers. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 2001;5:125–34.

Bernstein KT, Liu K, Begier EM, Koblin B, Karpati A, Murrill C. Same-sex attraction disclosure to health care providers among New York City men who have sex with men. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1458–64.

Mravcak SA. Primary care for lesbians and bisexual women. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:279–86.

Coker TR, Austin SB, Schuster MA. The health and health care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:457–77.

Flores SA, Mansergh G, Marks G, Guzman R, Colfax G. Gay identity-related factors and sexual risk among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;12:91–103.

Carrillo JE, Green AR, Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural primary care: a patient-based approach. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:829–34.

Merrill GS, Wolfe VA. Battered gay men: an exploration of abuse, help-seeking, and why they stay. J Homosex. 2000;39:1–30.

Houston E, McKirnan DJ. Intimate partner abuse among gay and bisexual men: risk correlates and health outcomes. J Urban Health. 2007;84:681–90.

Brown MJ, Groscup J. Perceptions of same-sex domestic violence among crisis center staff. J Fam Violence. 2009;24:87–93.

Sillman J. Diagnosis, screening, and counseling for domestic violence. UpToDate; 2010. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com. Accessed March 6, 2011.

Moracco KE, Cole TB. Preventing intimate partner violence: screening is not enough. JAMA. 2009;302:568–70.

Simmons T, O’Connell M. Married-couple and unmarried-partner households: 2000. Census 2000 Special Reports (CENSR-5). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2003. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/censr-5.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2011.

Acknowledgements

Contributors: The authors would like to acknowledge Curt Rogers and Iain Gill for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funders

None.

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ard, K.L., Makadon, H.J. Addressing Intimate Partner Violence in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 930–933 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1697-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1697-6