Abstract

Objectives

There is burgeoning interest in studying the effectiveness of mindfulness-based and traditional contemplative practices, and brief yet suitably and comprehensive measures of mindfulness are needed to assess related changes. There is preliminary evidence that pilgrimage may share some aspects with contemplative practices. This study examined the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the 15-item Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ-15) in a large sample of pilgrims and explored the effects of pilgrimage on mindfulness.

Methods

The FFMQ-15 along with distress and wellbeing measures were administered via online to a large sample of participants undertaking a pilgrimage (i.e., the Way of Saint James) in Spain (baseline: n = 800; pre-post analyses: n = 314). Confirmatory factor analyses were computed to find the best-fitting model of the FFMQ-15; reliability and construct validity analyses were also performed.

Results

The four-facet bifactor structure (mindfulness plus four specific facets, excluding observing) was the best-fitting model for the FFMQ-15 (CFI = .956; TLI = .931; RMSEA = .058 [.048–.068]; SRMR = .046). Overall, we found satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s α ranged from .56 to .85) and small to moderate correlations with distress and wellbeing measures.

Conclusions

The FFMQ-15 showed a four-facet bifactor structure and an overall satisfactory internal consistency and construct validity despite its shortness. We observed that mindfulness can be cultivated by pilgrimage, but further studies including long-term assessments and control groups are warranted before firm conclusions can be drawn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

During the last three decades, there has been burgeoning interest in studying the effects of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and traditional contemplative practices for promoting health and wellbeing (Goldberg et al. 2018; Khoury et al. 2015, 2017). In this regard, changes in mindfulness-related variables have typically been observed following mindfulness practice (Quaglia et al. 2016). In order to conduct such research effectively, there is a need to design reliable and valid self-report measures of mindfulness that can evaluate the effects of contemplative practices which are intertwined with mindfulness across a range of outcome variables and population groups.

The FFMQ is one of the most commonly employed measures for assessing mindfulness (Sauer et al. 2013). It is a self-report measure devised as a multidimensional questionnaire for assessing the dispositional tendency to be mindful in daily life (Baer et al. 2006). Baer et al. (2006) conducted an exploratory factor analysis with a large student sample who completed five mindfulness measures to provide an empirical and operative integration of all available mindfulness items into a reduced set of factors. In its original form, the FFMQ includes 39 items aggregated in five facets: Observing (noticing internal and external experiences), Describing (expressing internal experiences using words), Acting with Awareness (focusing on one’s activities in the moment), Nonjudging of Inner Experience (taking a non-evaluative stance toward own thoughts and feelings), and Nonreacting to Inner Experience (allowing thoughts and feelings to come and go, without getting caught up in or carried away by them).

The 15-item version of the FFMQ included the three items per facet that had showed the highest factor loadings in the original study (Baer et al. 2006). Recently, psychometric properties of the FFMQ-15 have been evaluated by Gu et al. (2016), demonstrating adequate internal consistency, convergent validity, and sensitivity to change. Regarding its dimensionality, a four-factor hierarchical model excluding the Observing facet provided the best fit in participants before receiving a MBI and a five-factor hierarchical model best fitted the data at post-treatment. In this regard, a lack of association of Observing with the other FFMQ facets has been consistently reported in samples without meditative experience (Baer et al. 2008; Bohlmeijer et al. 2011; Cebolla et al. 2012; Curtiss and Klemanski 2014; de Bruin et al. 2012; Lilja et al. 2011, 2013). In fact, the Observing facet has been positively related to psychopathology in meditation-naïve samples, probably because a misinterpretation of its items means that it becomes a construct more related to anxiety and self-focus on anxiety somatic symptoms rather than mindfulness (Baer et al. 2008; Desrosiers et al. 2014). Thus, it is recommended to exclude the Observing facet when scoring mindfulness in non-meditative samples (Baer 2019; Gu et al. 2016). Regarding the Spanish version of the FFMQ-15, according to Ortet et al. (2020), Cronbach’s α values oscillated between .69 and .80 for the total score. Regarding the five facets, Observing ranged from .56 to .66; Describing from .80 and .88; Acting with Awareness from .66 to .78; Nonjudging from .70 to .83; and Nonreactivity from .57 to .74. The internal consistency values oscillated depending on the type of sample (university students, general population, or general population that had participated in 6-week mindfulness course). Beyond personality traits, the Nonjudging facet was a significant predictor of subjective wellbeing.

Pilgrimage has been defined as a journey made in search of a place or a state which is considered to embody a set of ideals (Morinis 1992). Both religious and secular pilgrimages seem to share certain characteristics such as the ritual nature of the experience, walking toward a site considered special, cultural and mythological basis of the journey, existence of social and spiritual phenomena, and the transforming and “curative” nature of the experience (Warfield et al. 2014; Winkelmann and Dubisch 2005). Pilgrimage also appears to promote mindfulness-related psychological constructs as improvements in introspection, self-discovery, awareness of one’s emotions, detachment of personal burdens, connection with the present moment, and clarity in personal values and meaning are usually reported by pilgrims (Schnell and Pali 2013). Furthermore, repetitive attentive activities—such as walking with contemplation for several days—appear to foster states of greater awareness, self-inquiry skills, and transcendence (Schnell and Pali 2013). In this regard, it is also known that mind-body activities involving movement promote mindfulness, such as regular and sustainable practice of physical exercise (Demarzo et al. 2014; Goldstein et al. 2018; Salmon et al. 2010), tai-chi practice (Caldwell et al., 2011), collective dancing (Pizarro et al. 2020), or mindful-walking which is a type of formal practice in MBIs (Kabat-Zinn 1994). Additionally, pilgrimage has common aspects with silent intensive meditation/mindfulness retreats such as the appreciation of solitude, freedom from everyday tasks and routine such that life can be appreciated in the moment, and cultivation of mindfulness (Cheer, Belhassen and Kujawa 2017; Khoury et al. 2017). Consequently, there appears to be a degree of overlap in terms of the contemplative and psychological processes operating during both pilgrimage and mindfulness/meditation practices.

The objective of the present study was two-fold: firstly, to examine the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the FFMQ-15. Unlike previous studies, the dimensionality, reliability, and construct validity (relationship with depression, worry, stress, and wellbeing measures) of the FFMQ-15 will be evaluated without its items being embedded in the original 39-item form, as it is recommended for validations of short forms of scales (Smith et al. 2000); and secondly, to explore the potentially beneficial effects of pilgrimage on mindfulness facets. Regarding the first objective, considering previous evidence on the dimensionality of the Spanish FFMQ-39 (Aguado et al. 2015) as well as the unsuitability of the Observing facet in non-meditators, we expected that a four-facet bifactor model (without Observing) would yield a better fit than the other competing models. We also anticipated satisfactory reliability for the FFMQ-15 facets along with adequate construct validity. Concerning our second objective, we expected significant increases in FFMQ-15 facet scores after pilgrimage. Prior to this analysis, we tested the goodness-of-fit of the best-fitting solution for the FFMQ-15 at post-pilgrimage.

Method

Participants

In the present study, we utilized the “Ultreya” dataset. The Ultreya study is an online longitudinal study aimed at evaluating the effects of the pilgrimage on the Way of Saint James (“the Way”) on mental health and wellbeing (www.estudiocamino.org). This pilgrimage involves hundreds of paths around Europe with a common termination at Santiago de Compostela (Spain), and it was one of the most important Christian pilgrimages during the Middle Ages. Currently, it is walked by thousands of people (> 300,000 per year). A link to the Ultreya website is posted and shared across pilgrim associations, hostels, specialized websites, and social media.

The initial study sample comprised 2013 individuals with 1002 (49.8%) having Spanish nationality. Of these, 998 were Spanish-native speakers and 800 completed all FFMQ-15 items at baseline evaluation. Among them, only 583 were aimed at doing the Way during the recruitment and assessment timeframes of the present study. The 63% of these participants (n = 366) answered the post-pilgrimage assessment at the moment of database generation (314 fulfilled the FFMQ-15). Only subjects with complete FFMQ-15 data were retained in the psychometric analyses (T1: n = 800; T2; n = 314). For transparency and analytical reproducibility purposes, SPSS data and STATA syntax can be accessed at OSF: https:// osf.io/c6ygh/. Table 1 shows socio-demographic and scores on outcome variables of the participants.

As shown in Table 1, 800 Spanish pilgrims completed the online survey and comprised the final sample. Most respondents were women (approx. 60%) and middle aged, most were married or were living with a partner (around 49%), the immense majority had secondary education or higher (> 90%), and most were employed (> 70%).

Measures

The following battery of study measures were administered through a web-based platform (www.surveymonkey.com):

Socio-demographic Questionnaire

It collected information about gender, date of birth, marital status, educational level, and employment status.

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, 15-Item Version (FFMQ-15)

Items for developing the Spanish FFMQ-15 were extracted from the Spanish FFMQ-39 (Cebolla et al. 2012). This questionnaire measures trait-like tendency to be mindful in daily life and comprises five different related facets with three items each (see Supplementary Table 1 for more details of its content). Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never or very rarely true”) to 5 (“very often or always true”), and subscale scores may range from 3 to 15.

Patient Health Questionnaire, Short Form (PHQ-2)

This is a 2-item measure assessing frequency of the two core depression symptoms (depressed mood and anhedonia) over the past 2 weeks (Kroenke et al. 2003; Cano-Vindel et al. 2018), using a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “nearly every day”; total score ranges from 0 to 6). The Guttman’s split-half reliability in our sample was .78.

General Anxiety Disorder Scale, Short Form (GAD-2)

This is a 2-item scale that serves as an initial screening tool for generalized anxiety (Kroenke et al. 2007; Cano-Vindel et al. 2018). The scale assesses the frequency of “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge” and “Not being able to stop or control worrying” during last 2 weeks, using a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “nearly every day”; total score ranges from 0 to 6). The Guttman’s split-half reliability in our sample was .84.

Perceived Stress Scale, Short Form (PSS-4)

This scale measures the degree to which respondents appraise situations as stressful in the last month with responses scored on a Likert scale between 0 = “never” and 4 = “very often,” with total scores ranging from 0 to 40 (Cohen et al. 1983; Vallejo, Vallejo-Slocker, Fernández-Abascal and Mañanes 2018). Adequate internal consistency of the PSS-4 was found in the present study sample (α = .74).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

This scale assesses global life satisfaction and is used worldwide as a tool for measuring wellbeing (Diener et al. 1985; Vázquez et al. 2013). It contains five items rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”)—total scores range from 5 to 35. Excellent internal consistency was observed in the present sample (α = .89).

Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS)

This is a measure of global subjective happiness and consists of four items with a 7-point Likert-type scale. Total score ranges from 1 to 7, with greater scores indicating higher levels of perceived happiness (Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal 2014; Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999). Adequate internal consistency was observed in the present sample (α = .85).

Data Analyses

Data analyses were computed using SPSS v23.0 and MPlus v7.4.

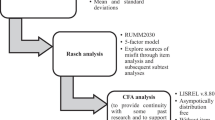

Dimensionality of the FFMQ-15

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) with maximum likelihood robust (MLR) as estimation method were computed using the whole study sample (n = 800). To replicate Gu et al. (2016), the following models were tested: (1) one-factor model with all items loading on one latent factor; (2) five-factor model including five correlated facets; (3) four-factor model (excluding Observing); (4) five-factor hierarchical model including an overarching factor with all of the 5 facets; (5) hierarchical 4-factor model including an overarching factor with all facets except Observing. Additionally, we also tested two bifactor models: one positing that all FFMQ-15 items loaded on a general latent factor of mindfulness and on five specific uncorrelated facets, and another model including all facets except Observing and one general latent factor of mindfulness. In bifactor models, item scores represent the joint functioning of both general (mindfulness) and specific (facet) factors. As an external validation of the best-fitting factor solution of the FFMQ-15, items from the FFMQ-15 were extracted from the original 39-item Spanish version and CFAs were conducted by using Aguado et al.’s (2015) sample. Finally, CFAs were also re-computed by using the Ultreya subsample with those participants who undertook the longitudinal assessment (n = 314), both pre- and at post-pilgrimage. Cut-offs for testing the fit of the evaluated models were used in accordance with Schermelleh-Engell et al. (2003) using conservative and liberal cutoffs (see al so Fan and Sivo 2007; Hu and Bentler 1999): CFI and TLI ≥ .95 or ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .06 or ≤ .08, and SRMR ≤ .05 or ≤ .10. Model comparisons were performed based on a practical improvement in model-fit approach (TLI difference of .01 or greater; Vandenberg & Lance 2000). For confirmatory purposes, all models were also re-run using data from the original Spanish validation (Aguado et al. 2015; n = 1191). The best-fitting model of the FFMQ-15 was retained for subsequent analyses.

Reliability Estimates

Cronbach’s α were calculated (values ≥ .60 are considered sufficient for exploratory research and ≥ .70 for confirmatory research (Hair et al. 1998). Omega (ω)—and omega hierarchical (ω-h)—coefficients (Brunner et al. 2012) were also computed by obtaining standardized estimates from the best-fitting CFA model. ω represents the reliability of a summed score formed with all of the factors comprising that score; and ω-h indicates the reliability of a summed score that consists of only one construct. In the case of FFMQ facets, low ω-h values would discourage the use of subscale scores. For comparative purposes, ω and ω-h were also calculated with Aguado et al.’s (2015) sample. Finally, as suggested by one anonymous reviewer, we also calculated coefficient H, which provides an estimate of the reliability of latent constructs when they are modeled with structural equation model techniques. Coefficient H is not affected by negative loading items, it can range from 0 to 1, and it is never smaller than the best indicator of the construct. High coefficient H values suggest a well-defined latent variable, being ≥ .60 the standard for tests used to measure group performance (Salvia and Ysseldyke 2001).

Construct Validity

We computed Pearson correlations between FFMQ-15 facets and the other study measures. For evaluating the strength of the correlation, Cohen’s (Cohen 1988) rule of thumb was used (i.e., ≥ .50: large; .30–.49: medium; .10–.29: small).

Changes in Mindfulness After Pilgrimage

Prior to analyzing pre-post changes in mindfulness facets by means of paired t tests, we computed the best-fitting model for FFMQ-15 at post-pilgrimage in order to reassure that this was a reasonable factor solution for our data once pilgrimage had finished.

Results

Dimensionality Analyses

The four-facet bifactor model showed the best fit as improvements respective to the second-best model (i.e., five-facet bifactor model) represented a practical improvement in model-fit approach (TLI difference ≥ .01). Fit indices of the four-facet bifactor model indicated good fit to the data according to conservative or liberal cut-off points. Fit indices of the tested FFMQ-15 models are presented in Table 2.

The best fitting model was again the four-facet bifactor model when all CFAs were performed with Aguado et al.’s (2015) sample. The fit indexes of this model were as follows: RMSEA = .036 [.028–.045]; CFI = .982; TLI = .972, showing a notably better fit than the second best-fitting model in that sample (i.e., the four-facet hierarchical model): RMSEA = .049 [.941–.056]; CFI = .962; TLI = .950. Means and SDs values for the FFMQ-15 items in the Ultreya sample were found to be similar to those found in Aguado et al. (2015) (see Table 3). The four-facet bifactor model was also the best-fitting solution in those participants who undertook the longitudinal assessment (n = 314), both at pre- and post-pilgrimage (see Supplementary Table 2 for more details).

The standardized factor loadings of the four-facet bifactor model ranged from small to large and varied considerably among items for the different facets. The items with the most problematic loadings on the general mindfulness factor were from the Nonreacting facet, with one item not reaching statistical significance (item 5; λ = .018), another item having a statistically significant negative factor loading (item 10; λ = − .294), and a third item showing a small factor loading (item 15; λ = .191). The other facets presented small-to-moderate factor loadings on general mindfulness factor (M = .381; range: .220 to .657). Regarding item loadings on specific mindfulness facets, values ranged from .276 to .861 (M = .437). In a similar way to Ultreya sample, when using an external validation sample (Aguado et al. 2015), poorer item loadings on the general mindfulness factor were observed for the Nonreacting facet with values ranging from .190 (item 10) to .364 (item 15). The item loadings of the other facets ranged from .351 to .633 (M = .368; general mindfulness factor) and from .424 to .737 (M = .480; specific factors). Regarding problematic items of the Nonreacting facet, a slightly better functioning was observed in Aguado et al.’s (2015) sample, but again items 5 and 10 were the most problematic ones (see Table 3 for more details).

Reliability

Cronbach’s α values ranged from .56 (Nonreacting) to .85 (Nonjudging) for FFMQ-15 facets; α = .74 was found for the total scale. The following coefficient H, ω, and ω-h values were obtained: .79/.79/.65 (Describing), .54/.78/.33 (Acting with awareness), .47/.86/.29 (Nonjudging), and .64.61/.61 (Nonreacting). The difference between ω and ω-h for the general factor (.85/.55) suggested that specific facets have considerable influence on the reliability of the FFMQ-15 total score. Similar findings were also found for Aguado et al.’s (2015) comparative sample. The coefficient H was .81 for the general factor (see Table 3).

Construct Validity

Correlations between FFMQ-15 total score and study variables were of mild-to-moderate magnitude, with negative associations with distress (rPSS-4 = − .53, rGAD-2 = − .44, rPHQ-2 = − .43; p < .001) and positive correlations with wellbeing scales (rSHS = .50, and rSWLS = .40; p < .001). Regarding the specific FFMQ-15 facets, Nonjudging presented significant (p < .001) correlations ranging from − .54 to − .49 for distress, and from .41 to .53 for wellbeing scales. On the other hand, the Nonreacting facet was least associated with the study variables, showing statistically significant associations (small effect sizes) with anxiety (r = − .08), perceived stress (r = − .11), and subjective happiness (r = .10) (see Table 4).

Longitudinal Measurement Invariance and Changes in Mindfulness After Pilgrimage

Goodness-of-fit results for the four-facet bifactor model at post-pilgrimage assessment are displayed in Table 2. As can be seen, this model was even slightly better than at pre-pilgrimage assessment. Significant increases in all subscales and total FFMQ-15 score were found after pilgrimage (all p < .001). Effect sizes were small and ranged from .17 (Nonreacting) to .37 for total score (see Table 5). Similarly, improvements (all p < .001) were also found in all outcome variables [PHQ-2: t = − 8.621; GAD-2: t = − 8.714; PSS-4: t = − 4.421; SWLS: t = 8.829; SHS: t = 10.206]. No differences (all p > .05) regarding sociodemographic, mindfulness, distress, and wellbeing variables were observed at baseline between Completers (n = 314) and Non-completers sample (n = 293) (see Supplementary Table 2 for more detail).

Discussion

Unlike previous psychometric analyses of the FFMQ-15 in which only one- and two-order factor structures were tested (Gu et al. 2016), bifactor models were also explored here as part of the dimensionality analyses. The four-facet bifactor model presented the best fit to our data. This result was in line with previous research excluding the Observing facet of the FFMQ in non-meditative samples (Baer et al. 2008; Bohlmeijer et al. 2011; Cebolla et al. 2012; Curtiss and Klemanski 2014; de Bruin et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2016; Lilja et al. 2011, 2013). Regarding functioning of the facets, it is noteworthy that items 5, 10, and 15 from the Non-reacting subscale presented poor (and, in case of item 10, even negative) loadings on the general factor of mindfulness. Interestingly, this poor functioning of Non-reacting items was also observed when using an external validation sample extracted from Aguado et al.’s (2015) study, suggesting that this finding was not exclusive of the Ultreya sample. However, slightly better psychometric properties for the FFMQ-15 were found in Aguado et al.’s (2015) sample. This difference may simply rely on the fact that data from their sample was obtained including the 15 items embedded in the FFMQ-39. Artificially superior psychometric properties (and higher factor loadings) are expected to be obtained when extracting items from the full-length instrument rather than measuring the short form in its own right (Smith et al. 2000).

Overall, acceptable reliability was found for Describing, Acting with Awareness, Nonjudging, and Nonreacting facets and the general mindfulness factor (all ω ≥ .60); we observed a poorer internal consistency than expected for the Nonreactivity subscale (α = .56), but this reliability coefficient has well-known limitations (McNeish 2018). It is noteworthy that this specific facet also showed lower reliability (α = .66) compared to the other subscales in the pioneer study by Gu et al. (2016). In the present study, the FFMQ-15 was administered without being embedded in the 39-item version (which was the case in Gu et al.’s study) and, consequently, the participants had less context to understand the meaning of the items. This could have had a role in lowering internal consistency for the facets (particularly so in the Nonreacting subscale) (Tran et al. 2013). Additionally, participants answered the FFMQ-15 without any support from research assistants who could ensure a proper understanding of the questionnaire, which could have also contributed to a worse internal reliability of the instrument compared to previous studies (Baer et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2016). It also important to also bear in mind that, because reducing the number of items of the scale also reduces its reliability, less stringent requirements for scales with small numbers of items are needed (Hair et al. 1998).

Our results regarding factor loadings and reliability are in congruence with previous studies (Veehof et al. 2011). A reformulation of the Nonreacting facet has been proposed previously to make the items more comprehensible (especially in people without meditative experience) and to improve the relationship with higher order factors of mindfulness and mental-health variables theoretically related to the construct (Tran et al. 2013). Unidentifiable problems in the translation of some specific items (especially item 10) and differences in the understanding of the items due to cultural context may be the cause of poorer functioning of the Nonreactivity facet in our sample. Similar problems in the Nonreacting subscale have also been recently reported recently in another short version of the Spanish FFMQ (Asensio-Martínez et al. 2019). Further studies in other cultures using the FFMQ-15 would shed more light into the functioning of the Nonreacting facet in the context of brief versions of the scale.

Mindfulness, as assessed using the FFMQ-15, was associated with distress and wellbeing variables. Nonjudging was the facet more strongly related to all outcome variables in line with the English validation study, in which this facet was found to present superior correlations with depressive symptomatology and negative rumination (Gu et al. 2016).

Significant increases were observed in the total and subscale FFMQ-15 scores, along with improvements in the psychopathological and wellbeing-related variables. Although effect sizes of changes in FFMQ-15 scores were found to be rather small, they were in line to those reported after mindfulness training (Quaglia et al. 2016). Notwithstanding, these positive findings should be interpreted with caution due to some methodological limitations, such as the observational nature of the data and the high number of dropouts (less than 50% of the participants completed the post-pilgrimage assessment). The inclusion of a control group of participants doing other activities (e.g., simply walking for being in a good fit) would have shed more light on the real healthy effects of pilgrimage. A more robust methodology is needed in other to ascertain whether the way of St. James is a healing trip for pilgrims that improves wellbeing at short and long-term.

Increases in mindfulness skills have also been reported following outdoor adventure therapy (Mutz & Müller, 2016), endurance sports (Salmon et al. 2010), tai-chi (Caldwell et al. 2011), and even using psychological interventions especially designed to not include MBI ingredients (e.g., Health Enhancement Program; Goldberg et al. 2016). This suggests that, beyond mindfulness/meditation training, there exist alternative ways to foster mindfulness cognitive skills which, in turn, are closely related to mental health and wellbeing (Xia et al. 2019). As stated by Goldberg et al. (2016), given that mindfulness may be considered “a set of cognitive, affective, and behavioural tendencies toward present moment awareness”, it is possible that without explicit instructions it can be cultivated “in more diverse ways than the literature on mindfulness interventions has assumed (p. 1013).”

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study has three main limitations that cannot be overlooked. Firstly, although online assessment has demonstrated to generate reliable data (Gwaltney et al. 2008), it has inherent limitations, such as self-selection bias and sample representativeness (Wright 2006). For instance, there are difficult-to-reach people characterized by digital illiteracy. Secondly, there are potentially reasonable explanations for the positive changes in mindfulness, distress, and wellbeing that might be not directly related to the experience of pilgrimage (e.g., it could just be the time away from stressors). As stated before, further studies including a control group (e.g., doing holydays or hiking routes) may allow a finer approach to evaluate causality between pilgrimage and psychological changes. We hypothesize that the positive impact on mindfulness, mental health, and wellbeing obtained with pilgrimage transcends those improvements that might be obtained with other leisure activities, but as stated above, this hypothesis remains to be tested by using an experimental design. Finally, we acknowledge that our study measures SHS and SWLS were both capturing an hedonic conception of wellbeing (Disabato et al. 2016), whereas it is reasonable to posit that mindfulness experiences and the pilgrimage in the Way of St. James might be more related to an eudaimonic conception of wellbeing (Delle Fave et al. 2011). A battery of short self-report sub-scales for assessing eudaimonic aspects of wellbeing (self-acceptance, personal relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, meaning in life, and personal growth) is described in detail elsewhere (Disabato et al. 2016). Future studies addressing the effects of pilgrimage on wellbeing might incorporate these sub-scales with the aim of capturing a holistic conception of this construct, being reasonable to hypothesize that pilgrimage might have a deeper impact on eudaimonic wellbeing than on hedonic wellbeing.

References

Aguado, J., Luciano, J. V., Cebolla, A., Serrano-Blanco, A., Soler, J., & García-Campayo, J. (2015). Bifactor analysis and construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ) in non-clinical Spanish samples. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00404.

Asensio-Martínez, Á., Masluk, B., Montero-Marin, J., Olivan-Blázquez, B., Navarro-Gil, M. T., García-Campayo, J., & Magallón-Botaya, R. (2019). Validation of Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire – Short form, in Spanish, general health care services patients sample: Prediction of depression through mindfulness scale. PLoS One, 14, e0214503. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214503.

Baer, R. (2019). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.10.015.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003.

Baer, R. A., Carmody, J., & Hunsinger, M. (2012). Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(7), 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21865.

Bohlmeijer, E., Klooster, P. M., Fledderus, M., Veehof, M., & Baer, R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18, 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111408231.

Brunner, M., Nagy, G., & Wilhelm, O. (2012). A tutorial on hierarchically structured constructs. Journal of Personality, 80, 796–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00749.x.

Caldwell, K., Emery, L., Harrison, M., & Greeson, J. (2011). Changes in mindfulness, well-being, and sleep quality in college students through taijiquan courses: a cohort control study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17, 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0645.

Cano-Vindel, A., Muñoz-Navarro, R., Medrano, L. A., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., González-Blanch, C., Gómez-Castillo, M. D., Capafons, A., Chacón, F., Santolaya, F., & PsicAP Research Group. (2018). A computerized version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 as an ultra-brief screening tool to detect emotional disorders in primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.01.030.

Cebolla, A., García-Palacios, A., Soler, J., Guillen, V., Baños, R., & Botella, C. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the five facets of mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). European Journal of Psychiatry, 26, 118–126. https://doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632012000200005.

Cheer, J. M., Belhassen, Y., & Kujawa, J. (2017). The search for spirituality in tourism: toward a conceptual framework for spiritual tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24, 252–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.07.018.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

Curtiss, J., & Klemanski, D. H. (2014). Factor analysis of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in a heterogeneous clinical sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36, 683–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9429-y.

de Bruin, E. I., Topper, M., Muskens, J. G. A. M., Bögels, S. M., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) in a meditating and a non-meditating sample. Assessment, 19, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112446654.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. P. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: qualitative and quantitative findings. Social Indicators Research, 100, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5.

Demarzo, M. M. P., Montero-Marin, J., Stein, P. K., Cebolla, A., Provinciale, J. G., & García-Campayo, J. (2014). Mindfulness may both moderate and mediate the effect of physical fitness on cardiovascular responses to stress: a speculative hypothesis. Frontiers in Physiology, 5, 105. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2014.00105.

Desrosiers, A., Vine, V., Curtiss, J., & Klemanski, D. H. (2014). Observing nonreactively: a conditional process model linking mindfulness facets, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and depression and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.024.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsem, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L., & Jarden, A. (2016). Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychological Assessment, 28, 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000209.

Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2014). The Subjective Happiness Scale: translation and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a Spanish version. Social Indicators Research, 119, 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0497-2.

Fan, X., & Sivo, S. A. (2007). Sensitivity of fit indices to model misspecification and model types. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701382864.

Goldberg, S. B., Wielgosz, J., Dahl, C., Schuyler, B., MacCoon, D. S., Rosenkranz, M., et al. (2016). Does the five facet mindfulness questionnaire measure what we think it does? Construct validity evidence from an active controlled randomized clinical trial. Psychological Assessment, 28, 1009–1014. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000233.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011.

Goldstein, E., Topitzes, J., Brown, R. L., & Barrett, B. (2018). Mediational pathways of meditation and exercise on mental health and perceived stress: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Health Psychology, 135910531877260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318772608.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Karl, A., Cavanagh, K., & Kuyken, W. (2016). Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based vcognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychological Assessment, 28, 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000263.

Gwaltney, C. J., Shields, A. L., & Shiffman, S. (2008). Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a meta-analytic review. Value in Health, 11, 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00231.x.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria vs. new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78, 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009.

Khoury, B., Knäuper, B., Schlosser, M., Carrière, K., & Chiesa, A. (2017). Effectiveness of traditional meditation retreats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 92, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.006.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41, 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004.

Lilja, J. L., Frodi-Lundgren, A., Hanse, J. J., Josefsson, T., Lundh, L. G., Sköld, C., Hansen, E., & Broberg, A. G. (2011). Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire-reliability and factor structure: a Swedish version. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40, 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2011.580367.

Lilja, J. L., Lundh, L. G., Josefsson, T., & Falkenström, F. (2013). Observing as an essential facet of mindfulness: a comparison of FFMQ patterns in meditating and non-meditating individuals. Mindfulness, 4, 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0111-8.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041.

McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23, 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144.

Morinis, A. (1992). Introduction: the territory of the anthropology of pilgrimage. In A. Morinis (Ed.), Sacred journeys: The anthropology of pilgrimage (pp. 1–28). London: Greenwood.

Mutz, M., & Müller, J. (2016). Mental health benefits of outdoor adventures: results from two pilot studies. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.009.

Ortet, G., Pinazo, D., Walker, D., Gallego, S., Mezquita, L., & Ibáñez, M. I. (2020). Personality and nonjudging make you happier: contribution of the Five-Factor Model, mindfulness facets and a mindfulness intervention to subjective well-being. PLoS One, 15(2), e0228655. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228655.

Pizarro, J. J., Basabe, N., Amutio, A., Telletxea, S., Harizmendi, M., & Van Gordon, W. (2020). The mediating role of shared flow and perceived emotional synchrony on compassion for others in a mindful-dancing program. Mindfulness, 11, 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01200-z.

Quaglia, J. T., Braun, S. E., Freeman, S. P., McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, K. W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28, 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000268.

Salmon, P., Hanneman, S., & Harwood, B. (2010). Associative/dissociative cognitive strategies in sustained physical activity: literature review and proposal for a mindfulness-based conceptual model. Sport Psychologist, 24, 127–156. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.2.127.

Salvia, J., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2001). Assessment (8th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sauer, S., Walach, H., Schmidt, S., Hinterberger, T., Lynch, S., Büssing, A., & Kohls, N. (2013). Assessment of mindfulness: review on state of the art. Mindfulness, 4, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0122-5.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8, 23–74.

Schnell, T., & Pali, S. (2013). Pilgrimage today: the meaning-making potential of ritual. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 16, 887–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2013.766449.

Smith, G. T., McCarthy, D. M., & Anderson, K. G. (2000). On the sins of short-form development. Psychological Assessment, 12, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.102.

Tran, U. S., Glück, T. M., & Nader, I. W. (2013). Investigating the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ): construction of a short form and evidence of a two-factor higher order structure of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 951–965. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21996.

Vallejo, M. A., Vallejo-Slocker, L., Fernández-Abascal, E. G., & Mañanes, G. (2018). Determining factors for stress perception assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and other European samples. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 37. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00037.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002.

Vazquez, C., Duque, A., & Hervas, G. (2013). Satisfaction with life scale in a representative sample of Spanish adults: validation and normative data. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.82.

Veehof, M. M., Ten Klooster, P. M., Taal, E., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Dutch Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) in patients with fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology, 30, 1045–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-011-1690-9.

Warfield, H. A., Baker, S. B., & Foxx, S. B. P. (2014). The therapeutic value of pilgrimage: a grounded theory study. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 17, 860–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2014.936845.

Winkelmann, A., & Dubisch, J. (2005). Introduction: the anthropology of pilgrimage. In J. Dubisch & M. Winkleman (Eds.), Pilgrimage and healing (pp. 10–36). Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

Wright, K. B. (2006). Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10, JCMC1034.

Xia, T., Hu, H., Seritan, A. L., & Eisendrath, S. (2019). The many roads to mindfulness: a review of nonmindfulness-based interventions that increase mindfulness. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25, 874–889. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2019.0137.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge the altruistic help of the pilgrims, “Xunta de Galicia,” “Agrupación de Asociaciones de Amigos del Camino del Norte,” and “Fundación Eroski”.

Funding

The corresponding author (JVL) has a Miguel Servet contract awarded by the Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCIII; CPII19/00003). JMM is supported by the WellcomeTrust Grant (104908/Z/14/Z/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AF-S: designed and executed the study, computed most data analyses, and wrote the first draft of the paper. AP-A: collaborated with the writing of the study. JVL: computed some data analyses and wrote part of the results. MD: collaborated with the design and writing of the study. MM: collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript. JS: collaborated with the design and writing of the study. WVG: collaborated with the writing of the study. JG-C: collaborated with the design and writing of the study. JM-M: assisted with the data analyses. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. AF-S and AP-A contributed equally to this manuscript and should be considered as co-first authors. JG-C and JMM share senior authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval was given by the Ethics Committee at the Sant Joan de Déu Foundation (PIC-141-19). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its following updates.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feliu-Soler, A., Pérez-Aranda, A., Luciano, J.V. et al. Psychometric Properties of the 15-Item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in a Large Sample of Spanish Pilgrims. Mindfulness 12, 852–862 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01549-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01549-6