Abstract

This paper illustrates a new project developed by a cross-country team of researchers, with the aim of studying the hedonic and eudaimonic components of happiness through a mixed method approach combining both qualitative and quantitative analyses. Data were collected from 666 participants in Australia, Croatia, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and South Africa. A major aim of the study was to examine definitions and experiences of happiness using open-ended questions. Among the components of well-being traditionally associated with the eudaimonic approach, meaning in particular was explored in terms of constituents, relevance, and subjective experience. The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) was also administered to quantitatively assess the hedonic dimension of happiness. Results showed that happiness was primarily defined as a condition of psychological balance and harmony. Among the different life domains, family and social relations were prominently associated with happiness and meaningfulness. The quantitative analyses highlighted the relationship between happiness, meaningfulness, and satisfaction with life, as well as the different and complementary contributions of each component to well-being. At the theoretical and methodological levels, findings suggest the importance of jointly investigating happiness and its relationship with other dimensions of well-being, in order to detect differences and synergies among them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Researchers in various disciplines have been increasingly involved in the investigation of one of the most complex and universally debated issues: the pursuit and achievement of the good life. Positive psychology was recently established as a new perspective specifically addressing the study of well-being, quality of life, strengths and resources (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Within this framework new theories, constructs and interventions have been developed. As a relatively recent framework, however, positive psychology still has much to gain from new ideas, approaches and assessment instruments (Richardson and Guignon 2008).

As noted by Waterman (1993) and Ryan and Deci (2001), researchers in positive psychology have investigated happiness primarily from two seemingly disparate conceptualizations: subjective well-being (hedonia) and psychological well-being (eudaimonia). The hedonic conceptualization of happiness focuses on the study of positive emotions and life satisfaction (Diener et al. 1985; Diener 2000; Pavot and Diener 2008) and includes an articulated framework such as Fredrickson’s (2001) Broaden-and-Build model of positive emotions. Other studies stem from Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia primarily considered in its subjective and psychological dimensions, rather than in its objective aspects, which are nevertheless part of the term’s original definition. These studies refer to a definition of happiness that comprises meaning, self-actualization and personal growth—at the individual level (Ryff 1989)—and commitment to socially shared goals and values—at the social level (Massimini and Delle Fave 2000). The contents of goals and meanings can differ across societies and cultures (Christopher 1999; Oishi 2000; Grouzet et al. 2005). Nevertheless, the pursuit of goals and the search for meaning in life events, interpersonal relationships and daily activities characterize human beings, as cultural animals (Baumeister 2005). These human features are components of theories and constructs such as psychological well-being (Ryff 1989), personal expressiveness (Waterman et al. 2008), sense of coherence (Antonovsky 1987), self determination (Ryan and Deci 2000, 2001), and psychological selection (Csikszentmihalyi and Massimini 1985). In particular, the increasing literature on meaning and the instruments developed to assess it have investigated the relationship of meaning with happiness, purpose in life, goal pursuit and achievement, and development of personal potentials (Chamberlain and Zika 1988; Linley et al. 2009; Morgan and Farsides 2009; Steger et al. 2006; Waterman et al. 2010).

However, more recently, this unilateral approach of examining either subjective or psychological well-being is increasingly being debated (e.g. Kashdan et al. 2008; Waterman 2008). This has resulted in the development of more integrated frameworks. For example, Seligman and others (Seligman 2002; Peterson and Seligman 2004) developed the orientations to happiness framework, which proposes that there are three different pathways to happiness; pleasure, engagement and meaning. Empirical evidence elucidates that a life filled with all three orientations leads to the greatest life satisfaction in comparison to a life with low levels of all three orientations, but that engagement and meaning are the most significant contributors to happiness relative to pleasure (Peterson et al. 2005; Vella-Brodrick et al. 2009). Keyes (2002, 2005, 2007) has also attempted to unify the eudaimonic and hedonic perspectives by introducing the concept of flourishing and developing a corresponding measure: the Mental Health Continuum, which assesses emotional, social and psychological elements.

In sum, the dichotomization of well-being into hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives has raised a fruitful debate within positive psychology, thus allowing scholars to bring some clarity into a domain which is still evolving and integrating previous works whilst also adding new insights. However, happiness and well-being are often used as synonyms, and this can generate ambiguities in the effort of defining these terms. Therefore, in this paper we will attempt to make a distinction between “happiness” as a construct empirically evaluated through qualitative and quantitative assessments, and “well-being” as a broader umbrella construct, that may have different meanings in different theoretical perspectives and that includes happiness. As suggested by the title of this paper, we assume as our point of departure that happiness may include more than hedonic components, and that eudaimonic aspects such as life meaning, growth and fulfillment may also be important constituents.

1.1 The Investigation of Happiness: Terminology, Constructs and Methodology

Positive psychology scholars still face a basic challenge: to find agreement on terminology. As previously stated, well-being and happiness are often used interchangeably. For example, from the hedonic perspective happiness is often considered synonymous with life satisfaction. Despite significant advancements in understanding happiness at both the theoretical and methodological levels, one crucial topic has been neglected: what do lay people refer to, when they speak about happiness? There are at least three issues that should be carefully addressed within this general question.

First, the definitions of happiness that are currently used stem from philosophical traditions, but their consistency with people’s understanding and expectations has not been directly verified with participants yet. Few studies have adopted a qualitative and exploratory perspective with diverse samples. Most studies have employed samples of college students making it difficult to generalize results. For example, Lu (2001) asked college students in China and Taiwan to describe what happiness was for them. Pflug (2009) did the same with German and South African students. In their analysis and interpretation of results, both researchers referred to the collectivist versus individualist perspectives. In one study, 61 Korean adults were asked what made them happy, but the sample was too small to include a broad range of possible answers (Kim et al. 2007). Furnham and Cheng (2000) also emphasized the importance of studying lay theories of happiness but they used a questionnaire with 38 items derived either from the literature or from interviews with lay people without providing sufficient detail on item selection.

Second, happiness itself is an ambiguous term, in that it conveys multiple meanings: it can be understood as a transient emotion (synonymous with joy), as an experience of fulfillment and accomplishment (thus prominently characterized by a cognitive evaluation), as a long-term process of meaning making and identity development through actualization of potentials and pursuit of subjectively relevant goals. In particular, throughout history, philosophers and thinkers from various cultures and traditions have often stated that happiness cannot be directly achieved: “to get happiness, forget about it” (Martin 2008, p. 171). Happiness usually arises as a by-product of cultivating activities that individuals consider as important and meaningful. Therefore, in order to understand happiness there is also a need to investigate meaning as the means available to individuals for pursuing well-being. The deeper understanding of these topics is not merely an academic exercise. For individuals and communities to flourish, it is essential that people develop their own capacities and resources (Keyes 2006; Sen 1992). Therefore, we need to better disentangle the contribution of hedonic and eudaimonic features and their interplay in promoting well-being of individuals and groups.

Finally, most instruments investigating happiness and well-being are built as scales: they do not allow for participants’ comments and descriptions. This can be considered a limitation, especially within a new perspective. It entails the risk of taking for granted that all over the world people build their idea of happiness on the opinion of Western psychologists and philosophers (Christopher and Hickinbottom 2008). The only exception to this trend is a study conducted by Lu and Gilmour (2006), who built a scale assessing various aspects of well-being on the basis of previous qualitative investigations with participants showing different cultural backgrounds. Grounding their analysis in the cultural conceptions of well-being, they found that Euro-American and East-Asian conceptions of subjective well-being systematically differ in that the former is more individual-oriented and the latter is more socially oriented.

1.2 The Eudaimonic and Hedonic Happiness Investigation: A Mixed Method Approach

Moving from these premises, adopting a pragmatist epistemology and a mixed method approach (Creswell 2008), we developed the Eudaimonic and Hedonic Happiness Investigation (EHHI) project, which attempts to explore qualitative aspects of happiness, described as an emotion—consistent with the hedonic perspective—and as a long-term process of growth and self-actualization related to meaning making—consistent with the eudaimonic perspective, as well as a quantitative evaluation of the degree of happiness and meaningfulness experienced in various life domains.

The EHHI aims to explore some specific features of happiness, and to relate them to other well-being components, in an attempt to obtain a clearer definition and operationalization of this controversial construct. First of all, how do people describe happiness? This topic is addressed by asking participants to define happiness in their own words. From the eudaimonic perspective, the EHHI explores the main meaningful things in people’s life through open-ended questions, taking into account two aspects of them, pointed out by Deci and Ryan (2000): their contents (the “what”) and their role in participants’ life trajectory (the “why”). The level of happiness and the level of meaningfulness ascribed by participants to 11 different life domains are also explored, by means of two rating scales.

The long-term aim of our project is to explore the role and relevance people attribute to various components of well-being in their definitions of happiness, and the relationship of happiness with life satisfaction and meaning. Due to the complexity and broadness of the attempt, in this first paper we will only focus on some of these aspects. We will introduce the EHHI and show findings related to (a) participants’ definition of happiness; (b) participants’ description of meaningful things; (c) the perceived levels of happiness and meaningfulness in the main life domains; and (d) the relationships between levels of happiness, meaningfulness and life satisfaction, the latter being assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985). In particular, the joint assessment with the SWLS and EHHI measures can highlight similarities and discrepancies between different conceptualizations of happiness. Moreover, it allows for the direct comparison between the levels of happiness and meaningfulness reported by participants in their life and their perceived life satisfaction. This integrated analysis can provide new insights for a better comprehension of the components of well-being.

In addition, by virtue of jointly using qualitative and quantitative data, this investigation may provide unique information on happiness and meaningfulness not gained through previous research which has tended to use only quantitative or single method approaches. The mixed-method nature of the current study will potentially enable new findings and theoretical interpretations of well-being to be drawn on the basis of the qualitative data, and the formulation of hypotheses based on the quantitative data. Firstly, based on qualitative data we will examine how people conceptualize happiness and its relationships with most meaningful things. We are interested in investigating whether the life domains in which people retrieve meaningfulness and happiness overlap or differ from each other. This information would help understand the role of these different components in promoting well-being, as well as their harmonization versus their conflict in daily life. Secondly, we predict that there will be discrepancies in the ratings of happiness and meaningfulness across the different life domains. We also expect to detect different correlation levels between happiness and meaningfulness ratings—on the one side—and the SWLS—on the other side. This hypothesis is grounded on the concept of flourishing (Keyes 2005), which highlights the complementary role of eudaimonic and hedonic aspects of well-being in promoting the good life. Finally, we will synthetically explore cross-country differences and similarities in both the qualitative and quantitative data. Since this is the first study presenting findings from the EHHI project, we will aggregate data across countries and mostly focus on descriptive analyses, with the view that more in-depth investigation of data from a cross-national perspective will shortly follow. Results can offer suggestions for conceptual advancements in the interpretation of happiness from an integrated perspective.

1.3 Aims of the Study

In this paper we aimed to introduce the EHHI and show some of the first findings, with a focus on definitions of happiness, meaningful things, and the relationships between levels of happiness, meaningfulness and life satisfaction, combining data across countries. Although significant differences among countries exist in some regards (Delle Fave et al. 2008), they are not the focus of the current paper. We will emphasize instead the potential of using a mixed method approach in the investigation of happiness and meaning, and its implications for the theoretical clarification of well-being, its connotative constructs and denotative phenomena.

Specifically, through qualitative analyses we investigated (1) how people define happiness, and (2) what things people consider most meaningful. The goals of quantitative analyses were (3) to compare the perceived levels of happiness and meaningfulness across life domains, and (4) to explore the relationships among levels of happiness, meaningfulness and life satisfaction. We expected to get new insights on the lay persons’ definition of happiness from the qualitative findings. We also assumed that the results of both qualitative and quantitative approaches would highlight the importance of the same constituents and sources of happiness. Finally, we looked for a deeper insight into the relationship between levels of happiness, meaningfulness and life satisfaction, in order to better clarify the contribution of hedonic and eudaimonic aspects to the definition of happiness and their interplay in promoting well-being.

2 Method

2.1 A Mixed Method Approach: Its Rationale and Aims

As previously reported, our data collection comprised two types of information—qualitative information derived from open-ended questions, and scaled ratings. Following Denzin (1978), this way of gathering data allows for methodological triangulation, defined as the use of multiple methods to study a single problem, which is in our case the ambiguity of the construct ‘happiness’ and its relationship to meaning. Our epistemological background to interpret qualitative findings is primarily phenomenology: we will attempt to investigate and understand what is the structure and essence of happiness and meaningfulness, according to the participants; however, we also rely upon a pragmatist perspective, with the aim of observing matters of interest in order to find out what is happening in human settings (Patton 1990). As described in detail in the next Procedure section, we also used the investigator triangulation within and across countries—the use of different researchers (Denzin 1978), who jointly worked at the data gathering and at the coding and categorization of the answers to the open-ended questions.

The decision of adopting a mixed method approach derived from the need to explore conceptualizations of well-being both from a lay person’s perspective and from the researchers’ perspective (as happens with quantitative methods). In our opinion, there is still much to learn on this topic in the well-being research domain. The use of qualitative assessment methods, such as open-ended questions, provides information about the participants’ perceptions, views and beliefs in their own terms, in contrast to using outside researchers’ definitions and categories, which is typical of quantitative inquiries (Denzin and Lincoln 2000). Qualitative data show an additional crucial feature: it is possible to convert them into quantitative scales for purposes of statistical analyses (Patton 1990). Therefore, qualitative information represents a basis for the development of more time-sparing and synthetic procedures that can be more easily administered and analyzed to bigger samples of participants. Finally, qualitative information can help develop and expand theoretical frameworks, by taking the researcher into the real world, so that the results are grounded in the empirical perspective (grounded theory approach, Glaser and Strauss 1967).

Our choice to use a mixed method approach was related to the attempt to get a view on happiness from the lay people’s perspective, through qualitative data, at the same time exploring (a) the perceived relevance of happiness in different life domains, (b) its relationship with meaning in these domains, as well as communalities and discrepancies of happiness and meaning when analyzed from the participants’ and researchers’ perspectives (through qualitative and quantitative data, respectively). We expected that this combined approach would help to illuminate some of the ambiguities about the construct of happiness, and to shed light on the relationship between happiness and meaning.

2.2 Participants

This study involved participants from seven different countries: Australia, Croatia, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain and South Africa, corresponding to the countries of the researchers involved in this international research project. We were interested in adult men and women in their productive life stage, with a high school diploma or higher education level. Because it is difficult to conduct qualitative research on a big sample, we decided to constrain the age range. We wanted to include mature people who are passing or have passed through some of the major life stages, like conclusion of the formal education, settlement in a job position, marriage and child bearing, thus expanding the repertoire of experiences on which participants can rely in their evaluation of happiness and meaningfulness.

The final sample comprised 666 participants from seven different countries: Australia (N = 99), Croatia (N = 104), Germany (N = 85), Italy (N = 104), Portugal (N = 78), Spain (N = 92) and South Africa (N = 104) who were aged between 30 and 51 years (51.7% below 41). All participants were living in urban areas. Participants were approximately equally distributed by gender (52.6% were female) and education level (48.3% had a high school diploma; the others had a university degree). As for occupation, 91.2% of the participants had a job. The most represented job categories were white collar workers such as academics, accountants and managers (29.4%), teachers (12.2%) and blue collar workers which included sales assistants, and factory workers (10.7%). The majority of participants were married or cohabited with a stable partner (59.2 and 12.2%, respectively), 19.9% were single and 7.1% were divorced. Most participants (65%) had children. As for religion, 74.5% were Christians (53.7% Catholic) and 21.4% atheist.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Eudaimonic and Hedonic Happiness Investigation (EHHI)

A questionnaire with a set of eight questions was submitted to the participants. Six of them were open ended questions, eliciting descriptions of happiness, goals and meaningfulness. For purposes of this paper the focus is on questions with regard to happiness and meaningfulness. Firstly participants were invited to define happiness in their own words. The question was “What is happiness for you? Take your time and provide your definition”. They were also asked “Please list the three things that you consider most meaningful in your present life”, followed by “For each of them, please specify why it is meaningful”. Two 1–7 point rating scales investigated the participants’ level of happiness and the level of meaningfulness associated with 11 different life domains: Work, Family, Standard of living, Interpersonal Relationships, Health, Personal Growth, Spirituality/Religion, Society issues, Community issues, Leisure, and Life in general. These domains were primarily identified on the basis of previous works aimed at investigating perceived quality of life, in particular the instruments and studies developed by the WHOQOL Group (1998, 2004, 2006). They included both objective (such as Work, Standard of living, Health conditions) and subjective indicators of well-being (such as Personal Growth and Spirituality/religion).

2.3.2 Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985)

Data were also gathered through the SWLS, which represents a well established and commonly used measure of the cognitive component of subjective well-being in the hedonic perspective. It is a 5-item scale that gives an indication of a person’s self reported general satisfaction with life according to his or her own criteria, measured on a cognitive-judgmental level. Participants rate their satisfaction with life on 1–7 point scales. Diener et al. (1985) reported a 2 month test–retest reliability index of .82, and a Cronbach Alpha-reliability index of .87. Pavot and Diener (1993, 2008) also attested to the good psychometric characteristics of this scale.

2.3.3 Socio-Demographic Questionnaire

A short socio-demographic questionnaire provided information on participants’ gender, age, level of education, work, standard of living, marital status, number of children, religion, and hobbies. Participants answered to each item using defined categories (gender, marital status, and standard of living) or open answer (age, level of education, work, number of children, and religion).

2.4 Procedure

2.4.1 Development of a Coding System

A pilot study on a sample of 80 participants from Croatia, Italy, and Portugal was initiated to develop a coding system. The three researchers involved in this first phase collected the data and subsequently discussed problems related to the item formulation and to the administration of the instrument. During several meetings, they jointly developed a coding system for the open-ended questions, based on coding strategies previously adopted for classifying similar typologies of answers (Delle Fave and Massimini 2004, 2005; WHOQOL 2006). In most cases, the answers to the open-ended questions could be categorized within the life domains for which the two rating scales assessed the levels of happiness and meaningfulness. However, some additional categories needed to be created for responses to the question about defining happiness. In these answers, participants often referred to specific life domains (describing happiness as job stability, positive development of children, respect for others, being healthy, enacting religious precepts in daily relationships, and living in a just society). However, they often provided purely psychological definitions of happiness as well, which were not contextualized within any specific life domain. Therefore, a set of categories was developed, referring to different psychological components of happiness, without any reference to specific daily contexts. The categories reflected the main constructs developed in the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives, such as “harmony” (e.g. being tuned with the world, inner peace), “emotions/feelings” (e.g. euphoria, positive feelings, moments of pleasure), “satisfaction” (with life; with oneself), “achievement” (of goals, dreams, wishes). This group of psychological categories replaced the domain originally defined as “Personal growth”, which was instead evaluated by the participants in the two rating scales, and which represented one of the coding categories for the open-ended questions referring to meaningful things. As participants often provided complex and multifaceted definitions of happiness—comprising 2.8 components on average—, it was decided to code up to six components for each participant.

In the final coding system, answers were transformed into codes distributed across 25 categories for the definitions of happiness, and across 12 categories for the answers to the meaningful things. In particular, 239 codes were obtained for definitions of happiness, and 276 codes for meaningful things. Through this preliminary sampling and coding it was possible to verify that all the answers to open-ended questions could be categorized adequately and that their classification could usefully refer to the same life domains used for the rating scales, except for the psychological definitions of happiness—as explained above.

2.4.2 Data Gathering

In the second sampling phase, researchers from four additional countries—Australia, Germany, Spain, and South Africa—joined the study. Data were therefore collected from seven countries with each researcher responsible for recruiting participants from the country in which they resided. In Croatia, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain the translation and back translation of the originally English instrument into local languages was performed, with the support of qualified professionals. Participants were recruited using a variety of methods including poster advertisements in public locations and word of mouth about the study. Prospective participants were provided with general explanations about the research project and if they consented they then completed the forms at a time and place convenient to them, and returned their responses to the researchers in person, via mail, fax, or email. All researchers were instructed to contact the designated coordinator for this research project (the researcher with significant expertise in qualitative research) with any questions regarding the process of translation, data collection or data input.

2.4.3 Coding Procedure

The researchers received detailed instructions for the coding procedure and data entry. In each country three researchers coded the answers to open-ended questions, with at least two researchers coding the same questions and answers. Any question, doubt or incongruence regarding the process of coding was discussed across countries and with the final decision of the designated coordinator.

3 Results

3.1 Qualitative Analyses

3.1.1 Definition of Happiness

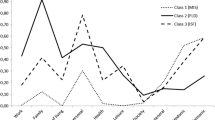

The majority of participants provided articulated answers to this question, except for seven, who stated that happiness is something unattainable and impossible to describe. Most definitions included more than one aspect of happiness. As reported in Figs. 1 and 2, the definitions referred in similar percentages to specific life domains (931 answers, 49.6%) and to psychological dimensions (916 answers, 51.4%). As Fig. 1 clearly shows, in over half of the answers referring to life domains, happiness was associated with relationships (Family 29%; Interpersonal Relations 26.9%).

Health and Daily Life followed with much lower percentages (12.1 and 10.6% of the answers, respectively). The latter category comprised unspecific and often fortuitous situations such as “no negative events”, “a good day”, “little things”, “to be in the right place at the right moment”.

As for psychological definitions of happiness (Fig. 2), the prominent category was Harmony/Balance (25.4%). It comprised items such as “harmony”, “balance”, “inner peace”, “positive relationship with oneself”, “contentment”, and “serenity”. Emotions/Feelings followed with the 16.6% of the answers; this category comprised items such as “positive emotion”, “joy”, “temporary happiness”, “cheerfulness, being merry”, “euphoria”, “feeling of comfort”, and “moments of pleasure”. Well-Being was the third category in rank (11.8%), comprising general answers such as “well-being” and “psychological/mental well-being”). Several other psychological dimensions were reported by the participants, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Key constructs in positive psychology, such as optimism, autonomy, achievements, purpose, engagement, and meaning were quoted. Satisfaction accounted for 7.2% of the answers.

3.1.2 Meaningful Things

Things people consider meaningful in their present life are presented in Fig. 3. Participants provided on average 2.9 answers referring to meaningful things. The prominence of Family as a meaningful component of life clearly emerged (39.9%), followed by Work (15.3%). Interpersonal Relations were ranked on the third place (10.5%). Health and Personal Growth were reported as meaningful life domains in 8.9% and 6.8% of the answers, respectively. Standard of living and Leisure activities were seldom quoted as meaningful aspects of life (with 5.1 and 4% of the answers, respectively). Society and Community issues, Spirituality/Religion, and Education got the lowest positions, each of them being quoted in less that 2% of the answers.

3.2 Quantitative Analyses

3.2.1 Levels of Happiness and Meaningfulness

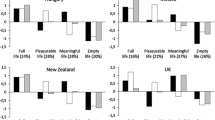

Table 1 shows the mean levels of happiness and meaningfulness reported by the participants across life domains on 1–7 point scales. Mean levels of meaningfulness were generally higher than mean levels of happiness. For some domains, like Family and Health, the values were close to maximum, thus showing a ceiling effect for these judgments. Meaningfulness for Family and Health domains deviated from normality (values for skew are about 2 and for kurtosis are above 2Footnote 1).

Looking at the specific domains, the highest level of happiness was reported for Family, followed by Health, Interpersonal Relations and then Personal Growth. The same four domains, in the same rank order, were rated as the most meaningful ones. In contrast, Spirituality, Community and Society issues were associated with the lowest levels of happiness and meaningfulness.

Domain-specific ratings of happiness and meaningfulness can provide information about the way people construct their global judgments. However, they can also provide information about participants’ evaluation of the relevance and role of each specific domain in providing happiness and meaningfulness. The rating scales comprised the evaluation of happiness and meaningfulness not only for the 10 specific domains, but also for Life in General. This allowed for exploring the extent to which these general and specific ratings were overlapping. Two regression analyses were computed to examine the degree to which each domain contributes to the explanation of the global happiness and meaningfulness ratings (Table 2). Domain intercorrelations for happiness and meaningfulness ratings are presented in the Appendix (Table 5).

In regard to happiness, the 10 domain-specific ratings explained 48% of happiness and 31% of Meaningfulness for Life in general. These results show that participants did not rate their overall life happiness and meaningfulness by merely summing up the level of these two dimensions in the specific life domains. Instead, they provided more detailed information about the specific aspects of their life.

3.2.2 Relationships Among Happiness, Meaningfulness and Satisfaction with Life

Table 3 shows the correlations of happiness and meaningfulness ratings in each life domain with the level of Satisfaction with Life. Correlations between happiness ratings across life domains and overall life satisfaction ranged from .20 to .47; the common variance between life satisfaction and these variables did not exceed 22%. The overall levels of happiness (assessed through the item “Life in General”) and life satisfaction shared only 30% of common variance. The correlations of life satisfaction with levels of meaningfulness in the different life domains were even lower, the highest correlation being detected for meaningfulness of Family (r = .25). Lower correlations between life satisfaction and meaningfulness (compared to happiness) may partly be explained by ceiling effects for some domains (Health and Family). Life satisfaction accounted for 6.25% of variance at most (Family), and for only 2.85% of the overall meaningfulness (Life in General).

The Satisfaction With Life Scale measures hedonic happiness. We wanted to find out the extent to which domain specific happiness and meaningfulness could explain life satisfaction. Specifically, we wanted to examine how much does meaning add to the prediction of life satisfaction above what can be predicted by happiness. A hierarchical regression analysis explaining life satisfaction was performed, with domain specific happiness levels entered in the first step, and domain specific meaningfulness entered in the second step (Table 4). It showed that the variance in life satisfaction was largely contributed by happiness rather than by meaningfulness. Happiness ratings across life domains explained 35% of the variance in satisfaction with life. Meaningfulness added only 3% to the explained life satisfaction variance. The small percentage of variance added by meaningfulness can partly be explained by ceiling effects for some meaningfulness judgments. In conclusion, happiness and meaningfulness assessments explained only 38% of life satisfaction variance, suggesting that 62% of life satisfaction was explained by some other factors.

We were also interested in investigating how much life satisfaction variance was accounted for by happiness once meaningfulness had been entered in the regression. In this situation meaningfulness explained 11.08% of life satisfaction variance (F 10, 515 = 6.42, p < .01), and happiness added 26.50% to the explained life satisfaction variance (F 10, 505 = 21.43, p < .01).

Finally, the mean levels of general happiness and meaningfulness were higher than the mean level of satisfaction with life, assessed with SWLS. As reported in Fig. 4, this pattern was true of all countries in this sample, although some differences in the mean scores were detected.

4 Discussion

The results of this study confirmed previous findings reported in the literature on happiness and well-being, and added some new insights to the understanding of the basic constructs and concepts investigated by researchers in this field. Firstly, the EHHI study provided qualitative information, mostly disregarded in currently used instruments, and secondly, it provided information on the relationships among various constructs and components of well-being that were jointly evaluated.

4.1 The Contexts and Content of Happiness

The definition of happiness can be analyzed from two different perspectives: the context (the life domains associated with happiness) and the content (the psychological structure and characterization of happiness). Participants in this sample provided both kinds of information, equally distributed in percentage across the two sub-categories.

As for contextual features of happiness, the relational aspect was prominent. Family and social relations accounted for over the half of the answers. Health followed as the third ranked domain. Considering these findings, happiness seems to stem predominantly from interpersonal bonds, mainly intimate relationships (with partner and children in particular) and interactions with friends and significant others outside the family. This conclusion applies for data combined across countries, but also for each of the individual countries involved in the study. As for the content of happiness at the psychological level, answers referred to both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects, but eudaimonic ones were prominent. The most frequently reported category, alone comprising over 25% of the answers, was Harmony/Balance. It is important to specify that in our categorization this dimension does not convey the interpersonal nuance often associated with it (Early 1997; Ferriss 2002; Ho and Chan 2009; Morling and Fiske 1999; Muñoz Sastre 1998). It does not necessarily refer to having good relationships with family or community members, although this may be part of it. The term reflects more specifically the perception of harmony at the inner level, as inner peace, self-acceptance, serenity, a feeling of balance and evenness that was best formalized by philosophical traditions in Asian cultures. As stated by Leung, Tremain Koch, and Lu (2002), considering harmony as the equivalent of conflict avoidance at the social level takes into account only one dimension of the concept of harmony. In the Chinese language, the term used for harmony includes such meanings as “gentle”, “mild”, “peace”, “quiet in mind and peaceful in disposition”. Chenyang (2008) points to another meaning of the Chinese term for harmony, quoted by the scholar Yan Ying (4th century BC): it refers to mixing different things and balancing opposite elements into a whole. Yan Ying uses cooking and making music as exemplary activities providing harmony through the balancing of different elements. In this perspective, harmony is a process rather than a state; it is the dynamic harmonization of various aspects and components of a whole. Such a conceptualization of harmony, as noted by Chenyang (2008), is deeply rooted in the Greek tradition as well, although framed within a different cultural and philosophical background. Examples of the Greek conceptualization of harmony are Pythagoras’s philosophy of numbers, the Stoics’ ideal of evenness of judgment and detachment, Plato’s definition of the just man—which relies on the balance between reason, spirit and appetites—and Epicurus’s concept of ataraxia (freedom from worries or anxiety). In particular, despite several misunderstandings throughout history, the idea of happiness proposed by Epicurus does not rely upon pleasure in hedonic terms. Rather it refers to the ability of the individual to maintain balance and serenity in both enjoyable and challenging times (Giannantoni 1976).

Other clearly eudaimonic dimensions, namely Engagement, Fulfillment, Meaning, Awareness, Autonomy, Achievement and Optimism, accounted all together for another 38.9% of the definitions of happiness. Hedonic aspects, such as positive Feelings/Emotions and Satisfaction were cited in 23.8% of the answers. Finally, a general feeling of well-being without specific connotations (including answers such as “feeling good/great”, “a feeling of well-being”, “well-being”) ranked third in frequency among the categories.

The twofold classification of happiness definition in contexts and contents emphasizes the complexity of the concept and the variety of interpretations it can convey. The answers provided by the participants are triggered by an open-ended question, which by definition does not presuppose salient dimensions or aspects. As highlighted by Patton (1990), the truly open-ended question “allows the person being interviewed to select from among that person’s full repertoire of possible responses…. One of the things the evaluator is trying to determine is what dimensions, themes, and image/words people use among themselves to describe their feelings, thoughts, and experiences” (p. 296). This approach allows for free expression of opinions and beliefs, while guaranteeing uniformity of formulation and reducing the influence of different interviewers.

The challenge of this kind of inquiry is the classification of answers in meaningful and heuristically useful categories. However, the categorization we adopted for our data found support in previous studies, at the same time expanding the conceptualization of happiness endorsed by these models, at both the levels of happiness contexts and content. The impressive prominence of relationships among the contexts of happiness—as well as among the most meaningful things—is not a surprise, in that previous models and theoretical frameworks underlined the positive impact of the social dimension on individual development and well-being. According to self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan 1985), living well involves those motives, goals, and behaviors that are satisfying of the basic psychological needs, one of them being relatedness. In Ryff’s model of psychological well-being (Ryff and Singer 2008), positive relations have their own specific role in promoting the good life. The other daily contexts are not specifically highlighted in these approaches, nor did they specifically emerge in our participants’ answers.

Regarding the content of happiness, both self-determination theory and the PWB model include psychological dimensions related to well-being that also emerged in our study, from the definitions of happiness classified as “psychological” ones. Autonomy, self-acceptance, purpose in life, competence and mastery are included in the categories we developed to group the definitions of happiness provided by the participants in our study. Autonomy coincides with one of our categories, self acceptance is included in “harmony”, mastery and competence are comprised in “achievement”, and purpose in life can be related with answers in the categories “meaning” and “engagement”.

Participants provided definitions that allowed for distinguishing internal dimensions of happiness (the content) and situational ones (the contexts). It can be argued that contextual definitions may comprise psychological aspects. For example, definitions of happiness referring to family included items such as “positive development of children”, “good relationship with partner”, “sharing within the family”, and “trust in partner”. Nevertheless, through them participants related the occurrence and meaning of such psychological definitions to a specific life domain. The two broad categorizations of context and content therefore do not substantially overlap. The psychological dimensions refer to general feelings and experiences lacking the relational and situational features which are instead prominent in the contextual definitions. Therefore, both aspects should be jointly evaluated when attempting to establish a definition of happiness. The use of contextual versus psychological definitions of happiness can also depend on the educational level of the participants, and on their more or less frequent use of abstract thinking and expressions. In our case, the homogeneity of the sample partially rules this problem out. However, further research is needed on this topic, which should also include possible cultural influences as part of contextual factors.

4.2 Constituents and Sources of Well-Being

The distribution of contextual definitions of happiness and meaningful things across life domains shed new light on the conceptualization of well-being, and provided insight to the questions we formulated in the introductory section of this paper. In particular, results showed that Family was the main domain attracting most of the participants’ resources and meaning making efforts. These findings, combined with the prominence of Family among the contextual definitions of happiness, highlight a global coherence in the domains associated with well-being in its different components, as well as its substantially relational core. This is true as found in the combination of data across countries, but also applies for each of the individual countries. Conversely, the low frequency of answers related to Society and Community issues (1.9%) contrasts with the prominence of Family, showing a clear demarcation line between public and private spheres of commitment. The minimal frequency of Spirituality/Religion is apparently in contradiction with the high percentage of participants who define themselves as followers of a religion.

The analyses performed on quantitative findings provided additional information, firstly highlighting the global consistency between qualitative and quantitative evaluations of happiness and meaningfulness. In particular the qualitative findings were confirmed and supported, showing the prominent association of Family with the highest levels of both happiness and meaningfulness. This consistency was also detected for the other domains. Namely, Interpersonal Relations and Health, following Family in rank among the definitions of happiness, and as meaningful life components, showed the same rank collocation in quantitative ratings. Analogously, Spirituality, Society and Community issues ranked last in the rating scales (except for South Africa), as well as in the categorization of happiness-related domains. This finding was further supported by their irrelevant presence among meaningful things for six of the countries. Only participants from South Africa reported high ranking of Spirituality/Religion in both happiness and meaningfulness ratings. This can be explained by the fact that data collection was primarily in an area of a previously Christian university. These results suggest that apart from possible cross-country and cross-cultural variables, the role of various socio-demographic factors should also be considered in future research on this topic.

The correlation and regression analyses highlighted some discrepancies between ratings of happiness, meaningfulness, and the widely explored construct of satisfaction with life. In particular, happiness and meaningfulness assessments explained only 38% of life satisfaction variance, suggesting that 62% of life satisfaction was explained by some other factors. One possible explanation of this finding concerns the relationship between domain-specific judgments and global ones. Global judgment is not equal to the sum of domain specific judgments: when people form their global judgments they rely on multiple sources, and these sources are weighted differently. According to another interpretation (which does not exclude the first one), happiness and meaning may have been interpreted by participants to include more psychological qualities aligned with the eudaimonic perspective, while the outcome variable of satisfaction with life is considered to be aligned with hedonic perspective. The two perspectives show a positive relationship, but they are also distinct and independent constructs.

These findings confirm previous evidence that well-being is a multifaceted concept, comprising different components that provide different and complementary contributions to its structure. These results also warn against the widespread tendency to use life satisfaction synonymously with happiness. Moreover, these findings highlight the need for further investigations of the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of happiness and well-being, in contrast with approaches which propose a unified model disregarding differences between eudaimonic and hedonic aspects, in favor of the latter components (Kashdan et al. 2008).

In particular, results showed that finding meaningfulness and experiencing happiness are not the same thing: they do not refer to the same life domains, and their perceived levels differ quantitatively in general and across domains. From this perspective, some discrepancies were detected concerning the relevance of hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions of well-being in specific domains. Exemplary is the case of the Work domain, which ranked second among the meaningful things cited by the participants, but only sixth among the happiness-related domains, and which was often qualitatively described as a means to other ends. This finding supports the hypothesis that meaning can be perceived and pursued in domains which do not provide hedonic happiness. This evidence contrasts the position of Waterman (2008), who maintains that eudaimonic well-being cannot exist in the absence of hedonic well-being. Other works confirm the plausibility of a condition in which high levels of eudaimonic well-being are combined with low levels of hedonic well-being (Keyes 2007). The opposite also emerged from the present findings in relation to the domain of Leisure: it is possible to perceive hedonic happiness independent of meaningfulness.

Finally, participants rated very differently their average levels of happiness, meaningfulness and satisfaction. In particular, they perceived their lives as predominantly meaningful, but satisfying to a lower extent. This pattern was found for all countries involved. Again, this result emphasizes the need for jointly evaluating different aspects of well-being, and for giving proper relevance to the eudaimonic dimensions in designing interventions.

5 Strengths, limitations and Future Directions

One of the main strengths of this study is the diversity of the cross-country sample. Firstly, the inclusion of samples from seven different countries and three continents provides a more diverse group of participants from which to evaluate the notion of happiness than is typically employed in well-being research, which tends to rely heavily on US participants. Secondly, researchers from each country were instructed to recruit respondents who fit specific demographic categories relating to age, education and gender, thus providing data which is balanced on these criteria. Moreover, it is likely that well-being is influenced by specific circumstances and needs associated with particular life stages, such as raising a family and paid employment. Hence, containing the study to participants aged 30–51 can provide more specific and pure information relating to this relatively homogenous group. However, the circumscribed distribution of participants as concerns age (limited the 30–51 range), education level (high school or college) and residence (urban areas) can also represent a limitation. The results cannot be generalized to other groups who do not fit the inclusion criteria. Hence, the study findings would need to be examined with more diverse samples in the future to ascertain if the results generalize across various life stages and socio-demographic factors. Future studies should include participants from non-Western countries, from other socio-demographic categories and other developmental phases.

Another strength of the current study concerns the use of both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. It allowed for the combined analysis of the experience of lay people and of researchers on the content and contexts of happiness. Although the inclusion of qualitative methods can be onerous to code and analyze, the richness of the data that it can produce is invaluable, particularly when exploring people’s interpretations of terms like happiness and meaning. The use of qualitative data in basic and applied research work is increasingly stressed in the most various domains. Just to draw on an example from an area traditionally endorsing the quantitative approach to research, such as medicine, NIH (2001) strongly recommends the use of qualitative information to shed light on the psychological and cultural dimensions influencing health, and several studies have recently adopted this approach (Luborsky and Sankar 2006). Psychological research concerned with well-being—which includes health among its crucial components—should pay more attention to this spreading trend.

A further step which could provide more insight into people’s interpretation of questions relating to happiness and meaning, is to investigate the cognitive appraisal processes employed by participants when responding to the questions. This will provide information about how consistently respondents are interpreting the question, which is important for standardization and comparison and whether the question is being interpreted by respondents in the way the researchers intended. For example, are respondents able to distinguish between “happiness” and “meaningfulness” when responding to questions asking them to rate various life domains in terms of these dimensions? Are respondents interpreting specific life domains such as “Interpersonal Relations” consistently?

The use of the current study’s approach for collecting data is a relatively unique in that it is not a standardized scale with accompanying psychometric properties that generates scale scores. Rather it is a combination of open and closed ended questions which seeks to explore respondents’ views from a broader framework. The use of such an approach may raise questions about its utility and validity for use in scientific and rigorous research. We argue that our approach is a strength in that it enables respondents to express their views on happiness and meanings with fewer constraints and predetermined ideologies and allows for more in-depth and variable responses than is typically gained from using quantified response options. This type of information is particularly useful in the initial stages of a research field, where the emphasis is on understanding and operationalizing the concept under investigation, from both practical and theoretical perspectives. Researchers in the field of happiness could benefit from this added insight as considerable discussion, speculation and debate remain about the constituents of happiness. It should be noted, however, that the current study included single-item measures of meaning and happiness. Future research should employ standardized measures of these constructs in addition to open-ended questions so as to balance the importance of exploratory research with that of rigorous and more controlled research.

6 Conclusion

Considering the exploratory nature of this study, results helped to operationalize the still evolving construct of happiness, and provided information on the content and contexts of eudaimonic and hedonic happiness, as shown in data combined across countries.

At the theoretical and methodological levels, findings clearly highlight the importance of jointly investigating the different aspects of happiness and their relationship with other dimensions of well-being, such as meaning and life satisfaction, in order to detect differences and synergies among them. The EHHI project is the first study which allows for this analysis.

The qualitative evaluation of the definition of happiness allowed us to detect a previously overlooked dimension, namely harmony/balance. This dimension refers to an even and peaceful attitude in dealing with life events, be they pleasant or unpleasant, and in achieving a balance between different needs, commitments and aspirations. It finds its roots in both the Asian and the Western traditions. Recently, Sirgy and Wu (2009) have focused on this topic in a theoretical paper which expands the threefold orientation to happiness model proposed by Seligman (2002), by adding to it the contribution of balance to well-being. Sirgy and Wu focus their analysis on the role of balance in promoting life satisfaction, the hedonic aspect of well-being, Further studies are needed to better disentangle this dimension and to investigate its role in enhancing well-being in its different components and facets.

At the interpretative level, results shed light on a trend which is apparently uniformly spreading in Western societies: well-being is prominently pursued and found in meaning and feelings confined to the home environment or to a close circle of friends. Community and Social issues are less valued as targets of resource investment. Data from non-Western countries are necessary to better frame the phenomenon, but in relation to the present sample, the pattern has been shown to be stable across the seven countries examined. This result contradicts Aristotle’s definition of eudaimonia as the fulfillment of one’s deepest nature in harmony with the collective welfare. Researchers and professionals will need to address this challenging issue, particularly when developing interventions targeting youth, education systems and policy makers.

Notes

Values in the range +2 to −2 are set by rule of thumb. The values of kurtosis are outside of the 95% confidence interval.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health - How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Baumeister, R. F. (2005). The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning, and social life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chamberlain, K., & Zika, S. (1988). Measuring meaning in life: An examination of three scales. Personality and Individual Differences, 9, 589–596.

Chenyang, L. (2008). The ideal of harmony in ancient Chinese and Greek philosophy. Dao, 7, 81–98.

Christopher, J. C. (1999). Situating psychological well-being: Exploring the cultural roots of its theory and research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 141–152.

Christopher, J. C., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory and Psychology, 18(5), 563–589.

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Massimini, F. (1985). On the psychological selection of bio-cultural information. New Ideas in Psychology, 3, 115–138.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Engeser, S., Vella-Brodrick, D., Wissing, M., et al. (2008). Eudaimonic happiness and the eudaimonic happiness inventory (EHI): A cross-cultural investigation. In Roundtable discussant and presenter at the 4th European conference of posiitive psychology, book of abstracts (pp. 99–100). Opatija, Croatia (July 1–4).

Delle Fave, A., & Massimini, F. (2004). Bringing subjectivity into focus: Optimal experiences, life themes and person-centred rehabilitation. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 581–597). London: Wiley.

Delle Fave, A., & Massimini, F. (2005). The relevance of subjective well-being to social policies: Optimal experience and tailored intervention. In F. Huppert, B. Keverne, & N. Baylis (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp. 379–404). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Early, P. C. (1997). Face, harmony and social structure: An analysis of organizational behaviour across cultures. NY: Oxford University Press.

Ferriss, A. L. (2002). Does material well-being affect non-material well-being? Social Indicators Research, 60, 275–280.

Fredrickson, B. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

Furnham, A., & Cheng, C. (2000). Lay theories of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 227–246.

Giannantoni, G. (1976). Profilo di storia della filosofia. Vol.1: La Filosofia Antica. [History of philosophy. Vol.1: Ancient philosophy]. Torino: Loescher.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Grouzet, F. M. E., Kasser, T., Ahuvia, A., Dols, J. M. F., et al. (2005). The structure of goal content across 15 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 800–816.

Ho, S. S. M., & Chan, R. S. Y. (2009). Social harmony in Hong Kong: Level, determinants and policy implications. Social Indicators Research, 91, 37–58.

Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 219–233.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Research, 43, 207–222.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2006). Subjective well-being in mental health and human development research worldwide: An introduction. Social Indicators Research, 77, 1–10.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108.

Kim, M. S., Kim, H. W., Cha, K. H., & Lim, J. (2007). What makes Koreans happy? Exploration on the structure of happy life among Korean adults. Social Indicators Research, 82(2), 265–286.

Leung, K., Tremain Koch, P., & Lu, L. (2002). A dualistic model of harmony and its implications for conflict management in Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 19, 201–220.

Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Osborne, G., & Hurling, R. (2009). Measuring happiness: The higher order factor structure of subjective and psychological well-being measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 878–884.

Lu, L. (2001). Understanding happiness: A look into the Chinese folk psychology. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 407–432.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2006). Individual-oriented and socially oriented cultural conceptions of subjective well-being: Conceptual analysis and scale development. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 36–49.

Luborsky, M., & Sankar, A. (2006). Beyond Nuts and Bolts: Epistemological and cultural issues in the acceptance of advanced qualitative and mixed methods research. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

Martin, M. W. (2008). Paradoxes of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 171–184.

Massimini, F., & Delle Fave, D. A. (2000). Individual development in a bio-cultural perspective. American Psychologist, 55(1), 24–33.

Morgan, J., & Farsides, T. (2009). Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 197–214.

Morling, B., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). Defining and measuring harmony control. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 379–414.

Muñoz Sastre, M. T. (1998). Lay conceptions of well-being and rules used in well-being judgements among young, middle-aged, and elderly adults. Social Indicators Research, 47, 203–231.

National Institutes of Health—NIH. (2001). Towards higher levels of analyses: Progress and promise in research on social and cultural dimensions of health. Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, NIH.

Oishi, S. (2000). Goals as cornerstones of subjective well-being: Linking individuals and cultures. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 87–112). Cambridge, MA: Bradford.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. CA: Newbury Park.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association/New York: Oxford University Press.

Pflug, J. (2009). Folk theories of happiness: A cross-cultural comparison of conceptions of happiness in Germany and South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 92(3), 551–563.

Richardson, F. C., & Guignon, C. B. (2008). Positive psychology and philosophy of social science. Theory and Psychology, 18(5), 605–627.

Ryan, M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13–39.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sirgy, M. J., & Wu, J. (2009). The pleasant life, the engaged life, and the meaningful life: What about the balanced life? Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 183–196.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning of life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93.

Vella-Brodrick, D. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Three ways to be happy: Pleasure, engagement, and meaning: Findings from Australian and US samples. Social Indicators Research, 90, 165–179.

Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678–691.

Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. The Journal Positive Psychology, 3(4), 234–252.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., & Conti, R. (2008). The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 41–79.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Bede Agocha, V., et al. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41–61.

WHOQOL Group. (1998). The WHOQL assessment instrument: Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine, 46, 1585–1596.

WHOQOL Group. (2004). Can we identify the poorest quality of life? Assessing the importance of quality of life using the WHOQOL-100. Quality of Life Research, 13, 23–34.

WHOQOL Group. (2006). A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 1486–1497.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to José Luis Zaccagnini (University of Malaga, Spain) and Stefan Engeser (Technische Institut, Munich, Germany), for their essential contribution in data collection and for their active participation in the coding phase of this study. We thank Marta Bassi (University of Milano, Italy) for her precious collaboration in different phases of the research work. We also thank our collaborators who helped in the coding process: Petra Anic, David Brodrick, Heleen Coetzee, Rocco Coppa, Carla Fonte, Isabel Lima and Michael Temane.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T. et al. The Eudaimonic and Hedonic Components of Happiness: Qualitative and Quantitative Findings. Soc Indic Res 100, 185–207 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5