Abstract

Objectives

Social approach and avoidance goals—which refer to individual differences in the desire to pursue rewards versus avoid negative experiences in social relationships—have numerous implications for the health and quality of social relationships. Although endorsement of these goals largely arises from people’s pre-dispositions towards approach and avoidance, in this research, we proposed that meditation training has the potential to beneficially influence the extent to which people adopt approach and avoidance goals. Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals who were randomly assigned to receive training in mindfulness or loving-kindness meditation would report differences in social approach and avoidance goals, as compared with those in a wait-list control condition, and that these effects would be mediated by differences in positive and negative emotions.

Methods

To examine these hypotheses, we drew upon a community-based, randomized intervention study of 138 midlife adults, who were assigned to receive mindfulness training, loving-kindness training, or no training in meditation.

Results

As compared with the control condition, results demonstrated that loving-kindness training was directly associated with lower social avoidance goals, and indirectly associated with greater social approach goals, via enhanced positive emotion.

Conclusions

These results suggest loving-kindness meditation is a means by which people can beneficially influence their approach and avoidance tendencies, which likely plays an important role in enhancing their social relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

When it comes to social relationships, motivation matters. Social approach and avoidance goals refer individual differences in the extent to which people tend to pursue rewards versus avoid threats in their close social relationships (Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012). These goals have important implications for relational outcomes, with approach social goals predicting a host of beneficial outcomes, and avoidance goals generally predicting maladaptive outcomes (Bernecker et al. 2019; Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012; Impett et al. 2010; Kuster et al. 2017). Given the centrality of healthy social relationships to mental and physical well-being (e.g., Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010; Santini et al. 2015), a key question is the following: is it possible for people to actively shift their social approach and avoidance tendencies? Although approach and avoidance social goals arise from biological and life-course pre-dispositions (Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012), an emerging body of research suggests that the extent to which people endorse approach versus avoidance goals can shift depending on contextual factors (Abeyta et al. 2015; Martiny and Nikitin 2019; Trew and Alden 2015). Despite this, no previous research has examined whether people can actively engage in behaviors that influence their approach and avoidance tendencies. In this study, we drew on research and theory from meditation and affective science (Creswell and Lindsay 2014; Fredrickson 2001; Fredrickson et al. 2008) to propose that mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation have the potential to beneficially influence the extent to which people endorse social approach and avoidance goals. That is, we suspected regular engagement in mindfulness or loving-kindness meditation would, relative to a control condition, promote greater identification with social approach goals and lower identification with social avoidance goals, and that these effects would be meditated by differences in positive and negative emotions. To examine these hypotheses, we drew on archival data from a community-based, randomized intervention study of 138 midlife adults who received training in either mindfulness meditation, loving-kindness meditation, or were assigned to a control condition.

Social approach and avoidance motivation refer to individual differences in the desire to create and seek out positive experiences versus prevent and distance from negative experiences in the social domain (Elliot et al. 2006; Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012). People who are high in social approach motivation are especially oriented towards creating positive moments, interactions, and experiences in their relationships, whereas people high in avoidance motivation tend to be wary of conflict, difficulty, and all types of negative experiences in their relationships. One of the ways in which social approach and avoidance tendencies manifest in everyday life is in the form of goals (Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012). According to approach-avoidance motivational theorists, people retain chronically accessible, dispositional tendencies towards approach or avoidance, and these dispositional tendencies for approach and avoidance arise and tend to influence proximal situational outcomes in the form of goals (Elliot and Church 1997; Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012). Social approach and avoidance goals are assessed as distinct from each other, meaning someone can highly identify with social approach and social avoidance goals, identify with neither social approach nor social avoidance goals, or highly identify with one and not the other.

Extensive research documents that approach and avoidance social goals have important implications for a wide variety of relational outcomes in all types of relationships, including romantic relationships and friendships. For instance, when individuals report greater social approach goals, it tends to be linked to enhanced friendships (Elliot et al. 2006), increased relationship satisfaction in intimate relationships for the individual and their partner (Impett et al. 2010), and beneficial intimate relationship behaviors, as rated by objective coders (Bernecker et al. 2019). Social avoidance goals, on the other hand, are linked to lower relationship satisfaction (Impett et al. 2010), greater fears of rejection (Elliot et al. 2006), and an increased frequency of relationship problems (Kuster et al. 2017). While it is not always the case that approach is good and avoidance is bad (see Scholer et al. 2019 for a discussion of this point), generally speaking, approach social goals tend to predict beneficial relational outcomes, whereas avoidance social goals tend to predict maladaptive outcomes.

Given that social relationships have an enormous impact on human health and well-being (e.g., Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010), and in light of the research reviewed above demonstrating the influence of approach and avoidance goals on social relationship outcomes, an important question arises: is there anything that people can do to beneficially shift their approach-avoidance tendencies? Approach and avoidance social goals are thought to arise (at least in part) from biological pre-dispositions and accumulated life-course experiences (Gable and Impett 2012), meaning it may be challenging for individuals to change these tendencies. Using avoidance social goals as an example, someone who is deeply afraid of negative social experiences (and therefore identifies with social goals aimed at avoiding conflict, embarrassment, and rejection) may find it difficult to change these goals, because their fear of rejection is based on relatively intractable factors, like their accumulated life-course history of challenging social experiences (Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012). Importantly, however, although it is true that social approach and avoidance goals do arise from long-standing motivational pre-dispositions, we note that it is not impossible for them to shift. Indeed, a growing list of studies have documented contextual factors that influence the extent to which people identify with social approach and avoidance goals (Abeyta et al. 2015; Martiny and Nikitin 2019; Trew and Alden 2015). What previous research has yet to document, however, is whether people may take active agency in the process of influencing their social approach and avoidance tendencies.

Mindfulness meditation typically involves training individuals to focus their attention on present-moment stimuli, while also becoming accepting of and open to whatever experiences arise in the present moment (Creswell 2017; Kabat-Zinn 2003; Shapiro et al. 2006). In addition to its beneficial influence on individual outcomes (e.g., enhanced coping with stress; Creswell and Lindsay 2014), an accumulating body of research demonstrates that mindfulness practice and dispositional mindfulness have benefits for social relationships, including in reducing the maladaptive impact of social threats (Brown et al. 2012), decreasing loneliness (Lindsay et al. 2019), and enhancing relationship satisfaction (Don 2020; Don and Algoe 2020). Given that numerous studies have documented how mindfulness promotes these broadly beneficial relational outcomes, it is possible that mindfulness training may influence social approach and avoidance goals. Crucially, however, no studies have examined if mindfulness training is linked to social approach or avoidance motivation.

The goal of loving-kindness meditation is for people to cultivate their capacity for kindness and compassion towards themselves, other people, and all beings (Salzberg 2002). To do so, in loving-kindness meditation, people are trained to cultivate warm and compassionate feelings, and repeat kind-hearted phrases towards a series of individuals, including oneself, loved ones, strangers, people with whom they struggle, and eventually, towards all beings (Fredrickson et al. 2008; Salzberg 2002). Empirical research has documented that when people receive loving-kindness training, it is associated with numerous benefits, including enhanced positive emotions, increased feelings of social connectedness, and beneficial psychophysiological changes (e.g., Fredrickson et al. 2017; Hutcherson et al. 2008; Le Nguyen et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2015). Given that (a) prior research has documented loving-kindness practice has benefits for feelings of social connectedness, and (b) loving-kindness practice has an explicit focus on fostering warmth and compassion towards other people, there is good reason to suspect loving-kindness meditation may enhance social approach motivation and reduce social avoidance motivation. Yet, as with mindfulness meditation, no studies have examined whether receiving training in loving-kindness meditation influences social approach or avoidance goals.

What is the exact mechanism by which mindfulness and loving-kindness practice may influence social approach and avoidance tendencies? There are many theoretical reasons to suspect both mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation practice may influence whether people endorse social approach and avoidance goals, but in this research, we draw on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson 2001, 2013), as well as theories of mindfulness and emotional regulation (Creswell and Lindsay 2014; Garland et al. 2015), to examine the possibility that mindfulness and loving-kindness practice influence social approach and avoidance goals by altering affective experiences (i.e., the experience of positive and negative emotions).

Positive and negative emotions are at the heart of approach and avoidance social motivation and goals (Elliot et al. 2006; Gable 2006; Impett et al. 2010; Kuster et al. 2017). For instance, feelings of hope for affiliation, enjoyment in relationships, and greater positive emotions in general are central to the endorsement of social approach goals (Don et al. 2020; Elliot et al. 2006; Gable 2006; Impett et al. 2010). Feelings like fear of rejection, relational anxiety, and worries about being hurt or embarrassed in relationships are central to the endorsement of social avoidance goals (Elliot et al. 2006; Gable 2006). Given the centrality of these positive and negative emotional experiences to social approach and avoidance goals, any factors that transform or help regulate positive and negative emotional experiences should likewise have consequences for social approach and avoidance goals, and extensive research demonstrates both mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation practice have the possibility to influence positive and negative affective experiences.

With respect to positive emotions, extensive research suggests that training in both mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation have the potential to promote positive emotions (we note here that the archival data we draw upon in this research was previously reported as one of two studies—in Fredrickson et al. 2017, Study 1—that documented the benefits of both mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation for positive emotions). For instance, in randomized controlled trials, individuals who receive training in mindfulness meditation experience greater positive emotions than people assigned to a control condition (Lindsay et al. 2019). Similarly, given that cultivation of warm, compassionate feelings is an explicit focus of the practice, one of the most consistent outcomes of loving-kindness meditation is that it promotes positive emotions (see Zeng et al. 2015 for a meta-analytic review). These increases in positive emotions associated with mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation likely have implications for social approach and approach goals. We base this proposition on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson 2001, 2013), which suggests that positive emotions expand the scope of an individual’s thoughts, actions, and perceptions, which allows them to build resources that are crucial to survival. According to this theory, one of the characteristic benefits of the “broaden” effect associated with positive emotions is it encourages the forging of social opportunities (Fredrickson 2013; Isen 1987). Indeed, extensive evidence supports these ideas, as people with greater positive emotions do tend to forge greater social connections, greater intimacy, and be more trusting of relationship partners (e.g., Dunn and Schweitzer 2005; Fredrickson et al. 2008; Waugh and Fredrickson 2006).

Based on these ideas, we believe positive emotions that arise from meditation practice may increase the extent to which people identify with social goals that emphasize opportunities for growth, connection, and enjoyment. For example, based on theory and existing evidence (Fredrickson 2013; Dunn and Schweitzer 2005; Fredrickson and Branigan 2005), an individual who experiences few positive emotions is likely to experience a narrower range of thoughts and action potentials, and therefore less likely to endorse social goals oriented towards enjoyment, growth, and connection (i.e., approach social goals). By contrast, someone who experiences a greater degree of positive emotion is likely to experience a wider range of thought-action potentials, including ones that forge new social connections. As such, for someone who is pre-disposed towards a low level of approach motivation, regular mediation practice could potentially enhance their approach tendencies, by promoting their experience of positive emotions.

Extensive research also suggests that receiving training mindfulness meditation is associated with beneficial changes in how people regulate negative emotions (Chiesa and Serretti 2009; Fogarty et al. 2015; Schumer et al. 2018). One of the key theorized benefits of mindfulness is that it allows people to openly acknowledge difficult or stressful experiences and accept them with an open and nonjudgment awareness (Brown et al. 2007; Creswell and Lindsay 2014; Lindsay and Creswell 2017). This may be especially helpful with respect to difficult social experiences: someone trained in mindfulness meditation may view potential conflict, rejection, or embarrassment as less threatening, because of their ability to regulate challenging emotions of all types. In this way, we suspected mindfulness training would predict lower avoidance motivation, via its influence on reduced negative emotions.

Although research suggests that loving-kindness meditation primarily has an influence on positive (but not negative) emotions (e.g., Fredrickson et al. 2008, 2017), we also thought it was possible that loving-kindness meditation would decrease social avoidance goals. In particular, because practitioners of loving-kindness meditation are encouraged to explicitly focus on cultivating warm-hearted attitudes and feelings towards other people (including people with whom the practitioner experiences difficulty), this practice may encourage people to be less wary of challenging interactions. A broaden-and-build perspective (Fredrickson 2013) suggests overt cultivation of positive emotions towards other people may ultimately result in a widened scope of thoughts and actions by which the individual may overcome fears of rejection, social anxieties, and worries in the social domain. This may ultimately translate into individuals high in positive emotions identifying with fewer social avoidance goals.

Based on the literature reviewed above, we tested 8 hypotheses which explored the possibility that training in mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation training would influence social approach and avoidance goals via the mechanisms of positive and negative emotions. We hypothesized that mindfulness meditation (Hypothesis 1A) and loving-kindness (Hypothesis 2A) meditation would predict greater identification with social approach goals as compared with a control group, and that these effects would be mediated by greater positive emotions (Hypothesis 1B and Hypothesis 2B). We also hypothesized mindfulness meditation would predict lower social avoidance goals (Hypothesis 3A), and that this effect would be mediated by decreases in negative emotion (Hypothesis 3B. Finally, we hypothesized that loving-kindness meditation would be related to lower identification with social avoidance goals (Hypothesis 4A), via the mechanism of greater positive emotions (Hypothesis 4B).

Methods

Participants

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01NR012899, supported by the NIH Common Fund, which is managed by the NIH Office of the Director/Office of Strategic Coordination. The underlying data supporting this manuscript have been used in prior publications with distinct aims (Fredrickson et al. 2015; Fredrickson, 2017, Study 1; Isgett et al. 2016; Le Nguyen et al. 2019). Participants for this study were midlife adults who were recruited from the community surrounding a major university in the Southeast of the USA. Participants were recruited via an informational e-mail on a university listserv, flyers posted in the community, and a Craigslist posting for the area surrounding the university. Participants ranged from 35 to 67 years old, and eligibility requirements included little to no meditation experience, internet access from their house, and no chronic illnesses or disabilities. A CONSORT diagram (based on the one originally presented in Isgett et al. 2016) provides an overview of recruitment and randomization for this study in Fig. 1. Additionally, all study materials and data analytic syntax are posted on the corresponding Open Science Framework page for this study, which can be viewed here: https://osf.io/tne8p/?view_only=1da11751d4c4450f9c9c0f304c9d99da.

Participants included in analyses for this study were on average 48.20 years old (SD = 8.74). One hundred and four participants identified as women (75.4%), while 34 (24.6%) identified as men. With respect to race, 80.4% of participants identified as White, 11.6% identified as Black or African-American, 7.2% identified as Asian, and 0.7% identified as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander. With respect to ethnicity, 4.3% of the sample identified as Hispanic.

Power analyses for the larger study from which these data are derived were calculated a priori based on other hypotheses. We utilized effect sizes from previous research examining mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation as they relate to affective and social processes as an approximation of the effect sizes they would likely obtain in this study, and estimated the number of participants needed in this randomized controlled trail. Information about these a priori power analyses can be found in (Le Nguyen et al. 2019).

Procedures

The procedures for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Upon recruitment to this study, participants first came to a laboratory for an intake session, where they provided demographic information and a number of assessments that are not relevant to the current investigation. Starting the Monday following the initial laboratory session, participants were then emailed daily surveys, which included daily reports of positive and negative emotions, and participants continued these reports throughout the duration of the intervention. One week after the initial intake, participants were randomly assigned (and notified about their random-assignment via e-mail) to one of three conditions: mindfulness meditation, loving-kindness meditation, and wait-list control (which involved no meditation training). During the intervention period, participants attended meditation classes, during which they received training in principles of loving-kindness or mindfulness meditation. The classes occurred once per week, and had a maximum enrollment of 16 people. Additionally, during the 3rd week of the intervention, participants completed a survey that included the measure of social approach and avoidance goals. We examined participants’ aggregated daily reports of positive and negative emotions during week 2 of the intervention as a mediator between the effect of the intervention and social approach and avoidance goals during week 3 of the intervention.

Across the course of the mindfulness intervention, participants were trained to focus their attention on the present moment with open and non-judgmental awareness, and were directed to progressively direct this attention to a series of different objects, including their breath, their body, and their thoughts. The ultimate goal of the intervention was to “re-perceive” the stream of present-moment experiences, so as to become less reactive and more open to all types of experiences (for further details of this intervention, see Fredrickson et al. 2017). The goal of the loving-kindness intervention was for people to develop their capacity for kindness and compassion towards themselves, other people, and all beings. To do so, participants who received loving-kindness training were instructed to generate warm and kind-hearted feelings, and then instructed to direct those feelings and a number of compassionate phrases (e.g., “May you be happy”) towards a series of different people, including oneself, loved ones, acquaintances, strangers, people with whom they have difficulties, and all beings.

Measures

Participants’ positive and negative emotions were assessed using daily versions of the modified Differential Emotions Scale (see Fredrickson 2013 for further details on the mDES). Participants reported the extent to which they experienced 10 sets of positive (“Glad, Happy, Joyful,” “Grateful, Appreciative, Thankful”) and negative (“Ashamed, Humiliated, Disgraced,” “Scared, Fearful, Afraid”) emotions over the past 24 hours on a scale from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely. A mean score was created for each subscale, and both subscales demonstrated good reliability (positive emotions α = .93, negative emotions α = .83).

Participants’ social approach and avoidance goals were assessed during week 3 of the intervention using a measure originally developed by Elliot et al. (2006). We note that the measure of social approach and avoidance goals—which is the primary outcome of interest in this research—was added to the larger study from which these data are derived initially as one of several secondary outcome measures. Participants completed 8 items, 4 of which assessed approach goals in social relationships (e.g., “In general, I am trying to share many fun and meaningful experiences with my friends.”; “In general, I am trying to enhance the bonding and intimacy in my close relationships.”), and four of which assessed avoidance goals in social relationships (e.g., “In general, I am trying to make sure that nothing bad happens to my close relationships.”). This measure is intended to assess social goals in friends, and across many types of relationships, and answers were provided on a scale of 1 = Not at all true of me to 7 = Very true of me. A mean score was created for each subscale, and both subscales demonstrated adequate reliability (approach α = .81, avoidance α = .77).

Data Analyses

We conducted data analysis in two steps. First, to examine the direct effect of the meditation intervention on social approach and avoidance goals (Hypotheses 1A, 2A, 3A, and 4A), we conducted two dummy-coded multiple regression analyses (one for approach goals and one for avoidance goals) to examine whether mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation could directly predict differences in social approach and avoidance motivation during week 3 of the intervention, as compared with the control condition. Next, to examine the indirect effects of the meditation interventions on approach and avoidance social goals (Hypotheses 1B, 2B, 3B, and 4B), we specified a structural path model in MPlus, which allowed us to simultaneously test whether there were indirect effects of mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation via positive and negative emotions on social approach and avoidance goals. We note that even in the case in which meditation conditions do not have a direct effect on social approach or avoidance motivation, as Kenny and Judd (2014) point out, it is often the case that tests of indirect effects are better able to detect the influence of an experimental manipulation on an outcome of interest. As such, even if mindfulness or loving-kindness meditation did not directly enhance social approach motivation or reduce social avoidance motivation, we thought it was possible we would identify an indirect effect via affective experiences. Additionally, if participants did not complete the key outcome measure of interest (the assessment of approach-avoidance social goals at week 3), they were not included in substantive analyses. As shown in the CONSORT diagram in Fig. 1, this resulted in 35 people being removed from substantive analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for major study variables are presented in Table 1. At the bivariate level, positive emotions during week 2 were associated with greater approach motivation during week 3 r = .23, p = .007, whereas counter to expectations, negative emotions during week 2 were not associated with either approach or avoidance motivation.

We first tested Hypotheses 1A, 2A, 3A, and 4A, which examine whether mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation have a direct influence on social approach and avoidance motivation. Results of separate multiple regression analyses predicting social approach or social avoidance motivation during week 3 of the meditation intervention are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2. We did not find support for Hypotheses 1A or 1B, as randomization to either mindfulness or loving-kindness meditation had no significant direct effect on social approach motivation (both p’s > .05). In support of Hypothesis 3B, participants randomized to the loving-kindness meditation condition reported significantly lower social avoidance motivation during week 3 of the intervention, as compared with participants in the control condition. We did not find support for Hypotheses 3A, as randomization to mindfulness meditation did not have a direct effect on social avoidance motivation. Thus, loving-kindness meditation specifically appears to have a direct influence in predicting lower social avoidance motivation.

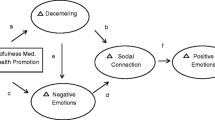

Next, we examined Hypotheses 1B, 2B, 3B, and 4B, which examine whether mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation are indirectly associated with social approach and avoidance motivation, via their influence on affect experience. To do so, we tested a structural path model in MPlus (Version 8; Muthén and Muthén 2017), which examined whether randomization to either mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation influenced social approach or social avoidance goals via affective experiences during week 2 of the intervention (i.e., the week immediately preceding the assessment of social approach and avoidance motivation). The path model was specified as presented in Fig. 3. All indirect effects were bootstrapped with 10,000 replications, and confidence intervals were bias-corrected, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Reflecting our hypotheses, as shown in Fig. 3, we specified paths in the model from the mindfulness meditation condition to both positive and negative emotions at week 2, and a path from loving-kindness meditation to positive emotions at week 2. Likewise, we specified paths from positive emotions to both social goals variables at week 3, yet only the single path from week 2 negative emotions to week 3 social avoidance goals. Finally, because loving-kindness meditation had a direct influence on social avoidance motivation in our test of Hypothesis 4B, in addition to the indirect path, we included a direct path to loving-kindness meditation to social avoidance goals.

Results of a structural path model examining indirect effects from meditation intervention condition to approach and avoidance social goals. Note. The control condition was set as the reference group. All coefficients are unstandardized. +p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01. The indirect effect of loving-kindness meditation on social approach goals was statistically significant, such that people in the loving-kindness meditation condition were indirectly more likely to report increased social approach goals, via the mechanism of increased positive emotions during week 2 of the intervention, estimate = .09, 95% CI [.003, .25]. All other indirect effects were not significant

Unstandardized coefficients are presented in Fig. 3. All model fit statistics suggested the model fit the data well (χ2 (4) = 3.83, p = .43, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = < .001, 95% CI [.0001, .11]). The bootstrapped tests of indirect effects of mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation on social approach and avoidance motivation via positive and negative emotions were the primary test of interests. We did not find support for Hypotheses 1B or 3B, as the indirect effects of randomization to the mindfulness meditation condition on social approach motivation (via positive emotions; estimate = − .008, 95% CI [−.10, .08]) and social avoidance motivation (via negative emotions; estimate = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, .01]) were both not significant. We did, however, find support for Hypothesis 2B: there was a significant indirect effect of randomization to the loving-kindness meditation condition on greater endorsement of social approach motivation, via greater positive emotions (estimate = .09, 95% CI [.003, .25]). We did not find support for Hypothesis 4B: although a significant direct effect emerged of loving-kindness meditation on lower avoidance social motivation (B = − 0.54, p = .005), no indirect effect emerged via positive emotions at Week 2 (estimate = − .001, 95% CI [− .07, .02]).

Additionally, because we tested all mediation hypotheses simultaneously, we wanted to ensure that the non-significant meditation paths were not due to the inclusion of all other variables in the path model. For instance, perhaps the non-significant indirect effect of mindfulness meditation ➔ negative emotions ➔ approach motivation was due to controlling for the other paths in the model. As such, we conducted ancillary analyses to ensure the non-significant paths in the structural path model were not merely a byproduct of testing the path model in this manner. When conducting these ancillary analyses, results confirmed the conclusions of original path model, suggesting the non-significant indirect effects, were not merely a facet of controlling for other variables in the model.

Discussion

Social approach and avoidance goals predict a multitude of important outcomes for close social relationships. Although these goals arise from dispositional tendencies for a need for affiliation and a fear of negative relational experiences, respectively, our objective in the current research was to test a hypothesis that mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation were a means by which people could actively influence their identification with these goals. Drawing upon archival data from a 6-week, randomized intervention study of midlife adults, results partially supported our hypotheses. Specifically, as compared with the wait-list control condition, loving-kindness meditation was (a) directly linked to lower endorsement of social avoidance goals, and was (b) indirectly related to endorsement of social approach goals, via its influence on positive emotions. The implications of these results are discussed below.

Meditation as a Means to Alter Social Motivation

One of the primary findings of this research was that when it came to social approach and avoidance motivation, the influence of mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation were not equivalent. That is, despite theory and prior research suggesting that both mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation could play a role in shifting social motivation, we found that only loving-kindness and not mindfulness meditation predicted social avoidance goals (directly) and social approach goals (indirectly) during the third week of the intervention. Why was this the case? Although there are many possible answers to this question, we feel two possibilities are especially worth mentioning here. First, it is possible that loving-kindness meditation has a particular influence on social approach and avoidance goals because it includes an explicit social focus within the meditation itself. The goal of loving-kindness meditation is to cultivate the practitioner’s capacity for kindness and compassion. To do so, practitioners envision and explicitly cultivate warm and tender feelings, and repeat kind-hearted phrases towards themselves and other people. Practitioners of loving-kindness suggest that it is this explicit social focus that is at the heart of why loving-kindness meditation confers unique benefits (e.g., Salzberg 2002). As such, this explicit rewarding social focus may have particular relevance for the endorsement of social approach and avoidance goals, which may explain why loving-kindness but not mindfulness meditation was linked to alterations in these outcomes.

Another possibility is that we only found an influence for loving-kindness and not mindfulness meditation because, contrary to prior research and theory (e.g., Creswell and Lindsay 2014; Fredrickson et al. 2017; Garland et al. 2015; Lindsay et al. 2019), mindfulness meditation was not associated with greater positive emotions or fewer negative emotions in this research. We note that this is in contrast to the previous report using this data (Fredrickson et al. 2017), which used all 6 weeks of the daily emotion reports, and found (in combination with another 6-week intervention study) that mindfulness did predict increases in positive emotions across the course of the intervention. In this research, because social approach and avoidance goals were assessed 3 weeks into the intervention, it is not possible to use these later reports of emotion. As such, one possible reason for the null associations between mindfulness meditation and the outcomes of interest in this research is because our assessments of emotions and social goals occurred early in the intervention period, during weeks 2 and 3 respectively. Had these assessments occurred later the intervention, the beneficial influence of mindfulness meditation on positive and negative emotions may have emerged, with potential consequences for social approach and avoidance motivations. Indeed, it is possible that meditation practice (for both mindfulness and loving-kindness) across longer periods time (e.g., later in our study, or across the course of years) may have a stronger influence on social approach and avoidance motives. Future research should therefore seek to examine how mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation may alter social approach and avoidance motivation across longer durations of practice.

Our results have theoretical implications for the literature examining social approach and avoidance motivation. Social approach and avoidance goals are theorized, in part, to arise from dispositional desires for affiliation (in the case of approach) and fears of rejection (in the case of avoidance; Gable 2006; Gable and Impett 2012). By demonstrating that endorsement of approach and avoidance goals differ depending on random-assignment to meditation training, our results provide evidence people may play an active role in shifting dispositional tendencies towards approach and avoidance, via meditation practice. More broadly, in accordance with an emerging literature providing evidence that approach and avoidance goals may change depending on contextual factors (e.g., Abeyta et al. 2015; Martiny and Nikitin 2019; Trew and Alden 2015), the results of this research suggest that while people’s social approach and avoidance goals are strongly influenced by their history of social experiences, it is not impossible for them to shift in a beneficial direction. This research, therefore, provides suggestive evidence for future research to continue to examine the factors that may beneficially impact social approach and avoidance tendencies, as it is possible that other behavioral modifications may promote beneficial changes.

Our results also have implications for the literature examining how meditation influences social relationship outcomes. An accumulating body of research demonstrates that loving-kindness meditation tends to promote broad feelings of social connectedness (e.g., Fredrickson et al. 2008; Hutcherson et al. 2008), but the specific pathways by which this happens are not well articulated. Given that social approach and avoidance goals have robust implications for behavior and outcomes in social relationships (Gable and Impett 2012; Impett et al. 2010), and that our study has now documented loving-kindness predicts shifts on social approach and avoidance goals, this research suggests that one reason why loving-kindness tends to promote broad social connectedness outcomes is by influencing the endorsement of social approach-avoidance goals.

Positive and Negative Emotions as Mediators

We posited that affect would play a central role in mediating the association between meditation interventions and social approach and avoidance goals, and in support of our broaden-and-build interpretation (Fredrickson 2013), we provided evidence of an indirect effect of loving-kindness meditation on social approach goals, via greater positive emotions. We note that although loving-kindness meditation was only marginally associated with greater positive emotions during week 2 of the intervention, as compared with the control condition, the indirect effect of loving-kindness meditation on greater endorsement of social approach goals via greater positive emotions was statistically significant. While we are generally hesitant to interpret marginally significant findings, in this case we make an exception for two key reasons: (a) a large body of research demonstrates that loving-kindness meditation has a robust influence on positive emotions (see Zeng et al. 2015 for a meta-analytic review), and (b) our primary hypothesis concerned the indirect effect of loving-kindness meditation on the social approach goals, via positive emotions. Given that this indirect effect was statistically significant, we felt the marginally significant association between loving-kindness meditation and positive emotions was less important than the statistically significant indirect effect. Results of the indirect effect suggest that, because loving-kindness meditation tends to promote positive emotions, one of the beneficial downstream consequences of loving-kindness practice is an indirect association with greater social approach goals. In this way, from a broaden-and-build perspective, the positive emotions that tend to emerge from loving-kindness training serve the function of building a social resource that is central to the promotion of healthy social relationships: social approach motivation.

Contrary to our predictions, despite the fact that loving-kindness practice had a direct influence on social avoidance goals, neither positive nor negative emotions explained this effect. There are a number of possible explanations for these findings, but we feel two are particularly plausible. First, it is possible that loving-kindness tends to impact social avoidance goals via mechanisms other than affect. For instance, one process through which loving-kindness meditation may influence social avoidance goals is through cognitive reappraisal. By repeatedly practicing goodwill towards others, individuals who are trained in loving-kindness meditation may learn to cognitively reappraise their difficult relationships. Second, we note that while previous research demonstrates a robust relationship between avoidance motivation and responses to negative events and experiences specifically in the social domain (e.g., Gable 2006; Kuster et al. 2017), the literature does not always clearly demonstrate an association between social avoidance goals and assessments of the individual’s general experience of positive and negative emotions outside of their relationships. Thus, had we assessed emotions specific to relationships, our mediation analyses may have been more sensitive in identifying these emotions as a plausible mechanism by which loving-kindness influences social avoidance goals. In light of these competing possibilities, future research is needed both to replicate our results and to explore the mechanisms by which loving-kindness may influence social avoidance goals.

Finally, it was surprising that participants’ negative emotions (a) were not influenced by either form of meditation, and (b) did not predict social approach and avoidance motives. These findings are contrary to prior research, which suggests that meditation interventions have a robust influence on negative affectivity (e.g., Schumer et al. 2018), and that negative emotions play a central role in social motives, particularly in social avoidance motivations (e.g., Gable 2006). Although there are numerous reasons for the lack of findings with respect to negative emotions, one possibility is the fact that participants reported few negative emotions during week 2 of the intervention. On a scale from 0 to 4, participants’ average ratings of negative emotions in the meditation conditions were 0.48, 0.46, and 0.52 for the mindfulness, loving-kindness, and control conditions respectively. The fact that participants experienced very few negative emotions during the intervention period may partially explain (a) why the meditation interventions seemed to have little influence on negative emotions early in the intervention, and (b) why negative emotions were not associated with approach and avoidance social goals.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our study is limited in several ways. First, because our outcome variable was a one-time assessment of social approach and avoidance motivation, we were unable to take full advantage of the daily nature of our assessments of positive and negative emotions. Specifically, we are unaware of quantitative methods that allow for predicting an outcome variable assessed at a single time point (approach or avoidance social goals) from a nested variable assessed across many time points (daily emotions; see (Krull and MacKinnon 2001 for a discussion of this point). Because of this, we used an average assessment of positive and negative daily emotions during week 2 of the intervention to predict approach and avoidance motivation during week 3 of the intervention in our mediation analyses. Second, because our study did not replicate prior research with respect to mindfulness meditation in promoting positive (Lindsay et al. 2019) and reducing negative emotions (Chiesa and Serretti 2009; Fogarty et al. 2015), it is possible that our lack of findings with respect to mindfulness meditation and social approach and avoidance motivations are study specific and reflective of the timing of our measures. Third, we are limited by our use of a one-time, self-report measure of social approach and avoidance goals. This is a limitation because it is possible that demand characteristics played a role in the results of this study. For instance, because people in the loving-kindness condition were frequently thinking about positive aspects of social relationships, it is possible they endorsed positive items related to social relationships on a self-report measure without actually changing their behavior. Fortunately, the assessments of social approach and avoidance goals we used in this study are well-validated, and consistently predict actual behavior in relationships (e.g., Bernecker et al. 2019; Impett et al. 2010). Regardless, future research should replicate these results with other types of assessments of approach and avoidance motives, such as daily experience and behavioral methods. Finally, we note demographic limitations of our sample. While we drew upon a relatively large, community-based sample, our participants were mostly White, and consisted solely of midlife adults. Noting that social relationship processes and interactions tend to be distinct across different life stages (e.g., Nikitin et al. 2014), adopting a meditation practice may have different influences on the social approach and avoidance motives of younger or older adults.

References

Abeyta, A. A., Routledge, C., & Juhl, J. (2015). Looking back to move forward: nostalgia as a psychological resource for promoting relationship goals and overcoming relationship challenges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 1029. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000036.

Bernecker, K., Ghassemi, M., & Brandstätter, V. (2019). Approach and avoidance relationship goals and couples’ nonverbal communication during conflict. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2379.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298.

Brown, K. W., Weinstein, N., & Creswell, J. D. (2012). Trait mindfulness modulates neuroendocrine and affective responses to social evaluative threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37, 2037–2041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.003.

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15, 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0495.

Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139.

Creswell, J. D., & Lindsay, E. K. (2014). How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 401–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414547415.

Don, B. P. (2020). Mindfulness predicts growth belief and positive outcomes in social relationships. Self and Identity, 19, 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2019.1571526.

Don, B. P., & Algoe, S. B. (2020). Impermanence in relationships: trait mindfulness attenuates the negative personal consequences of everyday dips in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37, 2419–2437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520921463.

Don, B. P., Fredrickson, B. L., & Algoe, S. A. (2020). Enjoying the sweet moments: does approach motivation upwardly enhance reactivity to positive interpersonal processes? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. (in press).

Dunn, J. R., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2005). Feeling and believing: the influence of emotion on trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 736–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.736.

Elliot, A. J., & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 218–232.

Elliot, A. J., Gable, S. L., & Mapes, R. R. (2006). Approach and avoidance motivation in the social domain. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 378–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205282153.

Fogarty, F. A., Lu, L. M., Sollers, J. J., Krivoschekov, S. G., Booth, R. J., & Consedine, N. S. (2015). Why it pays to be mindful: trait mindfulness predicts physiological recovery from emotional stress and greater differentiation among negative emotions. Mindfulness, 6, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0242-6.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 1–53). Burlington, VT: Academic Press.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19, 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000238.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262.

Fredrickson, B. L., Grewen, K. M., Algoe, S. B., Firestine, A. M., Arevalo, J. M., Ma, J., & Cole, S. W. (2015). Psychological well-being and the human conserved transcriptional response to adversity. PLoS One, 10, e0121839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121839.

Fredrickson, B. L., Boulton, A. J., Firestine, A. M., Van Cappellen, P., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M. M., Loundon, K., Brantley, J., & Salzberg, S. (2017). Positive emotion correlates of meditation practice: a comparison of mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation. Mindfulness, 8, 1623–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0735-9.

Gable, S. L. (2006). Approach and avoidance social motives and goals. Journal of Personality, 71, 175–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00373.x.

Gable, S. L., & Impett, E. A. (2012). Approach and avoidance motives and close relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00405.x.

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: a process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7, e1000316.

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8, 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013237.

Impett, E. A., Gordon, A., Kogan, A., Oveis, C., Gable, S. L., & Keltner, D. (2010). Moving toward more perfect unions: daily and long-term consequences of approach and avoidance goals in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 948–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020271.

Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 203–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60415-3.

Isgett, S. F., Algoe, S. B., Boulton, A. J., Way, B. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2016). Common variant in OXTR predicts growth in positive emotions from loving-kindness training. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 73, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.08.010.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016.

Kenny, D. A., & Judd, C. M. (2014). Power anomalies in testing mediation. Psychological Science, 25, 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613502676.

Krull, J. L., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2001). Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36, 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06.

Kuster, M., Backes, S., Brandstätter, V., Nussbeck, F. W., Bradbury, T. N., Sutter-Stickel, D., & Bodenmann, G. (2017). Approach-avoidance goals and relationship problems, communication of stress, and dyadic coping in couples. Motivation and Emotion, 41, 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9629-3.

Le Nguyen, K. D., Lin, J., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M. M., Kim, S. L., Brantley, J., Salzberg, S., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2019). Loving-kindness meditation slows biological aging in novices: evidence from a 12-week randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 108, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.020.

Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: monitor and acceptance theory (MAT). Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011.

Lindsay, E. K., Young, S., Brown, K. W., Smyth, J. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 3488–3493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813588116.

Martiny, S. E., & Nikitin, J. (2019). Social identity threat in interpersonal relationships: activating negative stereotypes decreases social approach motivation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 25, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000198.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus users guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nikitin, J., Schoch, S., & Freund, A. M. (2014). The role of age and motivation for the experience of social acceptance and rejection. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1943. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036979.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Salzberg, S. (2002). Lovingkindness: The revolutionary art of happiness. Shambhala Publications.

Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., & Haro, J. M. (2015). The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049.

Scholer, A. A., Cornwell, J. F., & Higgins, E. T. (2019). Should we approach approach and avoid avoidance? An inquiry from different levels. Psychological Inquiry, 30, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2019.1643667.

Schumer, M. C., Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Brief mindfulness training for negative affectivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86, 569. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000324.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237.

Trew, J. L., & Alden, L. E. (2015). Kindness reduces avoidance goals in socially anxious individuals. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 892–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9499-5.

Waugh, C. E., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). Nice to know you: positive emotions, self–other overlap, and complex understanding in the formation of a new relationship. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510569.

Zeng, X., Chiu, C. P., Wang, R., Oei, T. P., & Leung, F. Y. (2015). The effect of loving-kindness meditation on positive emotions: a metanalytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01693.

Funding

This research was financially supported by a research grant awarded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01NR012899) to Barbara L. Fredrickson, an award supported by the NIH Common Fund, which is managed by the NIH Office of the Director/Office of Strategic Coordination.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BPD: conducted data analyses and wrote the manuscript. SBA: provided collaborated in writing the manuscript, and consulted on the design of the study. BLF: designed the study, managed the collection of the data, and collaborated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Institution Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent prior to completing this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Don, B.P., Algoe, S.B. & Fredrickson, B.L. Does Meditation Training Influence Social Approach and Avoidance Goals? Evidence from a Randomized Intervention Study of Midlife Adults. Mindfulness 12, 582–593 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01517-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01517-0