Abstract

Objectives

Self-compassion-promoting components are increasingly included in parenting interventions. The strength of the evidence for the effectiveness of these components on self-compassion and both parent and child outcomes is unknown.

Methods

A systematic review of parenting intervention studies published between January 1st 2003 and February 8th 2019, that included self-compassion components and measured self-compassion quantitatively was undertaken. The outcomes of interest were the effect of these interventions on self-compassion and the effect of these interventions on both parent and child outcomes. Quantitative meta-analyses were conducted where appropriate.

Results

Thirteen trials met inclusion criteria. Results suggest that parenting interventions that include self-compassion components significantly increased parental self-compassion (pre-post: g = 0.372; between groups: g = 0.690). Pre-post analyses suggest that these interventions decreased parental depression (g = − 0.425), parental anxiety (g = − 0.377) and parental stress (g = − 0.363) and increased parental mindfulness (g = 0.529). Between-group and follow-up results for parent outcomes ranged from no effect to significant improvements. Five of the studies assessed the effects on child outcomes, with mixed results. Included studies were of low methodological quality, lacked control groups and generally failed to report study-level predictors and moderators of treatment effectiveness. There was also evidence of publication bias. Thus, the generalisability of findings may be limited.

Conclusions

Parenting interventions that include self-compassion components appear to improve parental self-compassion, depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness. Further research is needed to clarify these gains and to identify the mechanisms by which this benefit occurs, both for parents and their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parents are perhaps the single greatest influence in shaping the mental health and well-being of their children (Kessler et al. 2010; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). However, the numerous challenges experienced during parenting can have detrimental effects on the quality of parenting and can threaten the mental health and well-being of both parents and their children (e.g. McCue Horwitz et al. 2007; Sawyer et al. 2001). To date, many of the best-evidenced parenting programs are based on behavioural, cognitive and social-learning theory principles and target childhood conduct problems (e.g. Fossum et al. 2008; Furlong et al. 2013). More recently, researchers have begun to consider whether including components that target so called ‘third-wave’ cognitive behavioural therapy concepts (Hayes 2004) in parenting programs may be beneficial in improving parent and child well-being and mental health (e.g. Bögels et al. 2014; Coatsworth et al. 2014).

A large portion of this research has focused on the concept of mindfulness, which can be defined as ‘the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment’ (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p.145). Research suggests that parenting interventions that target parental mindfulness are effective at improving parental depression, anxiety, stress and general health (see Alexander 2018; Taylor et al. 2016 for reviews) and reducing preschool children’s externalizing symptoms (Townshend et al. 2016). Evidence has begun to emerge, however, which suggests that another closely related concept, that of self-compassion, may be an equally or more effective target of intervention in improving parent and child well-being and mental health (e.g. Beer et al. 2013; Gouveia et al. 2016).

Having self-compassion has been defined as ‘being open to and moved by one’s own suffering, experiencing feelings of caring and kindness toward oneself, taking an understanding, nonjudgmental attitude toward one’s inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one’s own experience is part of the common human experience’ (Neff 2003a, p. 87). Self-compassion is predominantly measured with the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003b), or the shortened version, the Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al. 2011). These scales measure an overall construct of self-compassion and six subscales, which reflect the conceptually distinct but related positively loaded elements of self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness and negatively loaded elements of self-judgement, isolation and overidentification (Neff 2003b; Neff et al. 2018). Self-compassion is also conceptualized as a set of skills that can be cultivated and strengthened through practical exercises (Salzberg 2009; Neff 2011). Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to improve participants’ scores on total self-compassion and all six subscales (Birnie et al. 2010). Neff and Germer (2013) suggested that mindfulness in self-compassion is more narrow than general mindfulness and refers to awareness of negative thoughts and feelings in relation to experiences of personal suffering only rather than all experiences. Self-compassion can be improved through other intervention components including self-compassion meditations and through practising self-compassionate reappraisals (e.g. Neff and Germer 2013; Smeets et al. 2014).

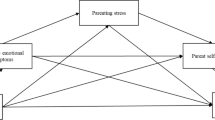

Cross-sectional research has identified that parental self-compassion correlates significantly and negatively with a range of factors related to parenting quality, such as parental depression (e.g. Felder et al. 2016; Fonseca and Canavarro 2018), parental anxiety (Beer et al. 2013; Felder et al. 2016), parental stress (Beer et al. 2013; Gouveia et al. 2016), child-directed criticism (Psychogiou et al. 2016), authoritarian and permissive parenting (Gouveia et al. 2016) and child behaviour problems (Beer et al. 2013). Two studies found that self-compassion-mediated relationships between factors related to parenting quality, such as maternal attachment–related anxiety and avoidance toward their own mothers on quality of life scores for their children (Moreira et al. 2015) and attachment anxiety and mindful parenting (Moreira et al. 2016). Many of these studies recommend that increasing parental self-compassion may be an effective target of interventions aimed at improving parenting quality (e.g. Felder et al. 2016; Psychogiou et al. 2016).

When designing interventions, it is essential that researchers target points of change and include intervention components that are as efficacious as possible. However, the strength of evidence for the effectiveness of parenting interventions that include self-compassion-promoting components is unknown. Thus, the aims of this paper are to assess the effectiveness of parenting interventions that include self-compassion-promoting components on parental self-compassion and to assess the effectiveness of these interventions on both parent outcomes and child outcomes. Our intentions are to use these findings to develop recommendations for future research.

Method

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2009; Shamseer et al. 2015). The review protocol was developed to follow the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews procedural outlines (Higgins and Green 2011). The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018078345). No ethics approval was required as no direct human data was collected.

Participants

Eligible studies were those that investigated samples of biological, adoptive or foster parents of an infant, child or adolescent aged between 0 and 18 years or expectant women. Studies were excluded if they were comprised of parents of adults or if they had less than 20 participants at the beginning of the intervention.

Interventions

Eligible studies included interventions that targeted parents and aimed to improve parent or child outcomes. The interventions were also required to include a self-compassion-promoting component, i.e. a component that would be reasonably expected to improve any of the positively loaded elements of self-compassion (i.e., self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness) or decrease any of the negatively loaded elements of self-compassion (i.e., self-judgement, isolation and overidentification).

Comparisons

Studies were included regardless of whether they utilized a comparison group or not.

Outcomes

Studies were required to include a measure of self-compassion as an outcome variable.

Study Designs

Studies were included if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal, in the English language, from the 1st of January 2003 up until the 8th of February 2019. Studies were included if they were a randomized control or comparison trial or a within-group, repeated-measures design. The commencement date was chosen because this corresponds with the year that the first known measure of self-compassion was developed and published. Case studies, case series and studies that did not include a quantitative analysis were excluded due to the limited generalisability of their findings.

Search Strategy

A search of the electronic databases PsychINFO (EBSCO), Scopus (Elsevier), Medline (Ovid), PubMed (NCIB) and CINAHL was conducted. The database search was run using a multi-field search format, with Boolean logic.

Study Selection

The retrieved studies collected were first screened to remove duplicates and then by title and abstract. Following this, the primary author (FJ) assessed the remaining articles based on a full-text analysis to determine eligibility, and a second reviewer (SS) assessed 50% of these studies selected at random. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion, and studies meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were retained for analysis.

Data Extraction and Management

Data extraction was undertaken by the primary author (FJ), and 50% of the data were checked by a second reviewer (SS). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data were extracted into a data extraction form designed for this review and piloted on two papers that met eligibility criteria prior to the data extraction phase. Data extracted consisted of study details, study sample size, population demographics, intervention details, definitions and measures of self-compassion used, details of the self-compassion-promoting components, measurement time points, outcome measures and information required to assess the studies methodological quality and risk of bias. Authors of eight papers were contacted to request the relevant statistics to enable their studies to be included in the associated meta-analyses.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias of randomized control studies were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins and Green 2011). Nonrandomized, within-subject, repeated-measures studies were assessed using the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS; Kim et al. 2013). The primary author (FJ) conducted the assessment of methodological quality, and a second reviewer (either SS or JM) independently assessed the methodological quality of 50% randomly selected studies. Disagreement between reviewers about bias were resolved through discussion that was informed by reference to existing research utilizing the RoBANS tool and Hartling et al. (2012).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA) version 3.0 (Borenstein et al. 2005). Hedges’ g effect sizes were calculated to quantitatively assess the effect of the interventions on self-compassion and parent and child outcomes. In order to maintain validity of the conclusions and robustness of the analysis, analyses were conducted when a minimum of four studies measured the same construct and provided the data required. Similar methods have been utilized in other studies (e.g. Bora et al. 2017). Hedges’ g is equivalent to Cohen’s d corrected for biases due to small sample sizes (Hedges and Olkin 1985). When interpreting effect sizes, Cohen (1988) suggested that 0.2 be considered a small effect size, 0.5 a medium effect size and 0.8 a large effect size. Post-intervention was defined as up to and including 1 month post completion of the intervention.

Pooled mean effect sizes were calculated using a random-effects model as considerable heterogeneity was expected (Borenstein et al. 2010). The Q-statistic was used to assess statistical heterogeneity between studies. A statistically significant Q rejects the null hypothesis of homogeneity. An I2 statistic was calculated to indicate the percentages of total variation across studies caused by heterogeneity. Higher values of I2 indicate greater heterogeneity, with 0% indicating no heterogeneity, 50% indicating moderate heterogeneity and 75% indicating high heterogeneity (Higgins et al. 2003).

Funnel plots of individual study effect sizes and, if asymmetric, Duval and Tweedie trim and fill method were used (Duval and Tweedie 2000). On a funnel plot, deviations from the expected pattern, of an upside-down funnel, indicate potential biases. The Duval and Tweedie trim and fill method (Duval and Tweedie 2000) tests for the presence of publication bias and where present, imputes removed studies and calculates a pooled effect-size estimate as if these were included.

Results

Study Selection

Our search strategy identified k = 541 records, no additional records were identified from our search of grey literature or reference lists of eligible studies. Of the identified records, k = 125 were identified as duplicates and removed and title and abstract screening removed a further k = 359 records. This left k = 57 studies for full-text review by two independent raters with disagreements about eligibility resolved through discussion. Consistent with our criteria, k = 14 studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the review and were selected for data extraction. Follow-up/secondary studies k = 1 were not included as additional studies but were encompassed with their relevant primary study. Thus, k = 13 studies were included in the final review. A PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process is represented in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies.

Study Characteristics

Population and Sample Demographics

Thirteen studies with a total of n = 809 participants were included. Sample sizes ranged from n = 21 to n = 178 participants. Eight studies included exclusively female populations and, while the remaining k = 5 studies targeted parents generally, they reported an overrepresentation of female participants ranging from 58 to 95%. It was not possible to report the mean age of children included across studies as child age was not reported in all studies. Thus, mean child age was not included in the data extracted to develop Table 1.

Six studies recruited participants from the community through advertisements and/or university research participation schemes; six studies recruited participants from clinical populations through health-care service referrals, self-referrals and/or flyers posted within health care facilities; k = 1 study recruited participants from staff at a workplace via an email flyer. Studies were conducted across five different countries: Australia (k = 3), Spain (k = 1), the Netherlands (k = 3), the UK (k = 3) and the USA (k = 3).

There was a high degree of variability in the parenting populations included across the studies. Six studies included women in the peri- or postnatal periods, including breastfeeding mothers (k = 2), pregnant women with mental health concerns (k = 2), mothers of infants who were experiencing mental health problems (k = 1), mothers of toddlers (k = 1) and mothers of infants in intensive care (k = 1). Two studies targeted parents of children with autism or a related disability; k = 2 targeted parents of children up to 12 years; k = 1 each targeted mothers of children aged 0–18 years, who were also healthcare workers, and mothers and fathers of young children with a history of depression. Five of the n = 13 studies targeted parents with clinically significant difficulties, and k = 3 studies targeted parents of children with clinical difficulties.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Of the k = 5 studies that targeted parents with clinical difficulties: k = 1 included participants based on self-report measures of elevated anxiety symptoms as assessed by the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al. 1990), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Item Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006); k = 1 administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; Gorman et al. 2004) and included participants if they reported 3 or more previous episodes of major depression and were in full or partial remission with no current substance dependence or bipolar disorder; k = 1 included participants if they were deemed at risk for perinatal depression or anxiety through an unstructured interview with a mental health clinician; and k = 2 studies included participants who had been referred by a mental health service as a result of experiencing maternal mental health problems or stress related to motherhood. One of the studies that assessed parents of children with autism or a related disability included participants based on results of a semi-structured interview, the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales—2nd Edition (VABS II; Sparrow et al. 1984), and k = 1 utilized the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-G/ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2000).

Study Design

Five studies used a randomized control trial (RCT) design with a waitlist/control group, and k = 8 studies used a repeated-measures design, without a control or comparison group. Seven of the studies compared measures at baseline and a single post-intervention time point, and the remainder included at least one other follow-up time-point.

Intervention Characteristics

There was a high degree of variability in the types of interventions used and the self-compassion-promoting components that were included across these studies. Three were compassion-based interventions, k = 9 were mindfulness-based interventions and Luthar et al.’s (2017) intervention was based on the Relational Psychotherapy Mothers’ Groups program (RPMG; Luthar and Suchman 2000; Luthar et al. 2007).

Three compassion-based interventions included brief components: a 15-min, guided Loving-Kindness meditation (Kirby and Baldwin 2018), a brief, online, self-compassion intervention (Mitchell et al. 2018) and a brief self-compassion writing induction exercise (Sirois et al. 2018). The mindfulness-based interventions were either based on mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn 1990) or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MCBT; Segal et al. 2002, 2013). Seven were 8-week courses, and k = 2 were 9-week courses, each with weekly sessions. Five of these studies stated that sessions were 2 h in length (Goodman et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2018; Perez-Blasco et al. 2013; Potharst et al. 2017). Ridderinkhof et al. (2018) reported 1.5-h long sessions, while Mann et al. (2016) and Townshend et al. (2018) did not report the length of their sessions. In Potharst et al.’s (2017) intervention, mothers brought their babies along to every session and in Potharst et al.’s (2018) intervention, mothers included their toddlers from session 4 onwards. Mendelson et al.’s (2018) intervention included only one initial session and then 2 weeks for participants to practice at home before completing post-intervention assessments. Luthar et al.’s (2017) RPMG-based intervention ran for 12 weeks, as weekly 1-h group sessions.

Mitchell et al.’s (2018) intervention was the only intervention that focused entirely on developing self-compassion skills. Kirby and Baldwin’s (2018) study included mindfulness and instructed participants to direct compassion toward themselves. Sirois et al. (2018) included a brief self-compassion writing induction. The mindfulness-based interventions targeted improving the ‘mindfulness’ element of self-compassion, and k = 4 studies also included other types of self-compassion-promoting components. These were as a session focus topic (Perez-Blasco et al. 2013; Townshend et al. 2018), through self-compassion meditations (Goodman et al. 2014) or through explicit instructions to participants to be kind to themselves (Jones et al. 2018). Luthar et al.’s (2017) intervention included a range of components that may target different elements of self-compassion including a large focus on building social connection and explicitly exploring self-compassion as part of session 10.

Definition and Measurement of Self-Compassion

Mitchell et al. (2018) and Sirois et al. (2018) were the only two studies that explicitly provided a definition of self-compassion, both taken from Neff (2003b). All but one of the studies measured parental self-compassion outcomes with a version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003a), a self-report measure that gathers continuous data. Seven studies used the original measure, k = 2 used the Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al. 2011) and k = 3 studies used a 3-item unpublished version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-3; Raes and Neff, unpublished manuscript). Mendelson et al. (2018) used 4 items adapted from the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003b) and Sirois et al. (2018) used a 5-item ‘State Self-Compassion’ measure adapted from Breines and Chen (2012). All studies administered the measure at all measurement time-points, except Kirby and Baldwin (2018) who omitted it at baseline and Sirois et al. (2018) who administered the Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al. 2011) at baseline and utilized the ‘State Self-Compassion’ measure adapted from Breines and Chen (2012) at post-intervention. All studies reported results for the total self-compassion score, and only Perez-Blasco et al. (2013) reported subscale results.

Quality Assessment

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the critical appraisal ratings for included studies. Table 2 presents a summary of methodological quality of RCT studies derived from the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs (Higgins and Green 2011). Kirby and Baldwin (2018) and Sirois et al. (2018) demonstrated the least overall bias, each being assessed as demonstrating additional bias only in the form of limitations in reporting on sample population. Luthar et al. (2017) was assessed as demonstrating bias in the areas of performance and potential conflict of interest. Mann et al. (2016) and Perez-Blasco et al. (2013) were both assessed as demonstrating bias in the areas of performance and potential conflict of interest, together with attrition and sample population. Many studies did not report on these issues, and risk, deemed ‘unclear’, was assessed as being present across studies.

Table 3 presents a summary of methodological quality of pre-post intervention studies, derived from the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS; Kim et al. 2013). Bias was identified in all pre-post studies included in our review. Goodman et al. (2014), Luberto et al. (2017), Potharst et al. (2017) and Potharst et al. (2018) were all assessed as demonstrating high risk in selection bias and high sample risk. Jones et al. (2018) and Mitchell et al. (2018) were both assessed as having bias related to attrition; additional bias was assessed in Mitchell et al. (2018) with respect to selection. Ridderinkhof et al. (2018) was assessed as demonstrating bias with respect to medication in in performance, and Townshend et al. (2018) and Mendelson et al. (2018) were free of bias with the exception of potential sample bias.

Effect of Parenting Interventions that Include Self-Compassion-Promoting Components on Self-Compassion

Quantitative analysis was used to assess the effects of the interventions on self-compassion at post-intervention. Follow-up effects were assessed using narrative synthesis due to the small number of studies that conducted follow-up assessments and the considerable heterogeneity in follow-up length across the studies.

Of the thirteen studies, k = 9 studies provided the required data and were included in a quantitative analysis of the post-intervention within-group effects on parental self-compassion. All effect sizes were positive and ranged from small to large (0.192 to 0.772), except for Mendelson et al. (2018) who provided a small negative effect size (− .146). The overall within-group Hedges’ g for self-compassion at post-treatment was small-moderate, at 0.372 (p = < 0.0001, 95% CI = 0.203 to 0.540) and heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 59.325, Q = 19.668, p = 0.012). Inspection of the funnel plot suggested the presence of publication bias, in favour of studies with positive outcomes. Figure 2 presents the associated forest plot, and Fig. 3 presents the associated funnel plot. As a result, k = 3 studies were imputed, and using the Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill method, the overall Hedges’ g reduced to a small effect of 0.224 (CI = 0.140 to 0.307) and heterogeneity increased (Q = 35.457).

Publication bias detected by funnel plot for within-group effect of interventions on self-compassion. Unfilled circles represent included studies. Black circles represent imputed studies. Unfilled diamond represents observed summary estimate. Black diamond represents the summary estimate if all imputed studies were included

The five RCTs were included in the final between group analysis of effects on self-compassion. Between-group treatment effect sizes for self-compassion ranged from small to large (0.294 to 0.940). The overall between-group Hedges’ g for self-compassion was moderate, at 0.690 (p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.445 to 0.935). Heterogeneity was not indicated (Q = 4.46, p = 0.346, I2 = 10.476). Inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate evidence of publication bias. Figure 4 presents the associated forest plot, and Fig. 5 presents the associated funnel plot.

Four studies reported medium or large effects on self-compassion at follow-up. Two studies found that the post-intervention effects were maintained over time, and one RCT (Luthar et al. 2017) and one repeated-measures study (Potharst et al. 2017) found that they increased significantly further over time.

Effect of Parenting Interventions that Include Self-Compassion Components on Parent Outcomes

A variety of parent outcome measures were assessed across the interventions. The most common were parental depression, parental anxiety, parental stress and parental mindfulness and were thus included in further analyses. Quantitative analyses were conducted for the within-group, post-intervention effects of the interventions on parental depression, parental anxiety, parental stress and parental mindfulness. Between group and follow-up effects were assessed using narrative synthesis due to the small number of studies that measured the same parent outcomes.

Effect on Parental Depression

Of the n = 7 studies that included outcome measures of depression, n = 5 supplied the data required and were included in the quantitative analysis of the post-intervention within-group effects on parental depression. Within-group treatment effect sizes for depression ranged from small to large (− 0.763 to − 0.159). The overall within-group Hedge’s g for depression was small-moderate, at − 0.425 (p < 0.001, 95% CI = − 0.589 to − 0.260). Inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate evidence of publication bias. Heterogeneity was low (Q = 4.458, p = 0.348, I2 = 10.271). Figure 6 presents the associated forest plot, and Fig. 7 presents the associated funnel plot.

For between-groups comparisons at post-intervention, n = 1 RCT (Luthar et al. 2017) found that the intervention group reported significantly lower depression scores of moderate effect and two reported no difference (Mann et al. 2016; Perez-Blasco et al. 2013). One repeated-measures study (Luberto et al. 2017) and n = 2 RCT’s (Luthar et al. 2017; Mann et al. 2016) looked at follow-up effects and found that depression symptoms had decreased significantly from those demonstrated at post-intervention.

Effect on Parental Anxiety

Of the n = 6 studies that included outcome measures of anxiety, n = 4 supplied the data required and were included in the quantitative analysis of the post-intervention within-group effects on parental anxiety. Within-group treatment effect sizes for anxiety ranged from small to large (− 0.772 to − 0.234). The overall within-group Hedge’s g for anxiety was small-moderate, at − 0.377 (p < 0.005, 95% CI = − 0.597 to − 0.156). Inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate evidence of publication bias. Heterogeneity was low (Q = 4.483, p = 0.214, I2 = 33.087). Figure 8 presents the associated forest plot, and Fig. 9 presents the associated funnel plot.

For between-groups comparisons at post-intervention, one RCT (Perez-Blasco et al. 2013) reported a significant and large decrease favouring the intervention group at post-intervention. One study (Luberto et al. 2017) found that the large reductions observed at post-intervention were maintained at follow-up.

Effect on Parental Stress

Of the n = 7 studies that included outcome measures of stress, n = 5 supplied the data required and were included in the quantitative analysis of the post-intervention within-group effects on parental stress. Within-group treatment effect sizes for stress ranged from small to moderate (− 0.527 to − 0.221). The overall within-group Hedge’s g for stress was small-moderate, at − 0.363 (p < 0.001, 95% CI = − 0.498 to − 0.228). Inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate evidence of publication bias. Heterogeneity was not indicated (Q = 2.078, p = 0.721, I2 = 0). Figure 10 presents the associated forest plot, and Fig. 11 presents the associated funnel plot.

For between-groups comparisons, Luthar et al. (2017) did not find a significant difference in stress for the intervention group compared with the control at post intervention; however, an effect of medium-large effect size was observed at follow-up. For follow-up results, three repeated-measures studies (Luberto et al. 2017; Potharst et al. 2018; Ridderinkhof et al. 2018) found that reductions observed at post-intervention increased or were maintained at at-least one follow-up time point.

Effect on Parental Mindfulness

Of the n = 10 studies that included outcome measures of mindfulness, n = 5 supplied the data required and were included in the quantitative analysis. Within-group treatment effect sizes for mindfulness ranged from 0.343 to 0.714. The overall within-group Hedge’s g for mindfulness was moderate, at 0.483 (p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.334 to 0.632). Inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate evidence of publication bias. Heterogeneity was not indicated (Q = 2.835, p = 0.586, I2 = 0). Figure 12 presents the associated forest plot, and Fig. 13 presents the associated funnel plot.

Mann et al. (2016) found no significant difference between groups in an RCT at post-intervention. Perez-Blasco et al. (2013) reported subscale measures of the FFMQ and found between-group effects ranging from no effect to large effects across the different subscales. Two within-group studies also reported subscale measures of the FFMQ only and found no effect to large effects across the different subscales (Mendelson et al. 2018; Potharst et al. 2018). At follow-up, two repeated-measures studies (Luberto et al. 2017; Ridderinkhof et al. 2018) found that the significant effects observed at post-intervention were maintained at follow-up, while two studies (Potharst et al. 2017; Potharst et al. 2018) and an RCT (Mann et al. 2016) found that follow-up effects improved over post-intervention effects.

Effect of Parenting Interventions that Include Self-Compassion Components on Child Outcomes

Four studies assessed the effects of the interventions on child outcome measures. Three studies measured child behaviour, and one measured infant behaviour; however, it was decided that, as they targeted developmentally distinct populations, they were too discrepant to justify inclusion in a meta-analysis. Jones et al. (2018) found no changes in child prosocial behaviour and behavioural difficulties at post-intervention. Potharst et al. (2017) found significant and moderate increases in infant positive affectivity immediately post-intervention (p < .05; β = .48) and that these were maintained at 8 weeks post-intervention. They also found a small to moderate increase in infant orienting and regulatory capacity post-intervention (p < .01; β = .35); however, this was no longer statistically significant at follow-up. No significant effects were reported for measures of infant negative emotionality. Potharst et al. (2018) found a moderate decrease in parent reported child psychopathology (p < .05, d = .65) at post-intervention, which was maintained at both 2-month (p < .05, d = .74) and 8-month follow-up (p < .05, d = .54). Potharst et al. (2018) also found a borderline significant improvement in child dysregulation of small effect size, which increased and remained significant at 2-month and 8-month follow-up. Ridderinkhof et al. (2018) assessed a range of child outcome measures and found significant and small to moderate reductions on social communication problems (p < .01, d = .32), internalizing symptoms (p < .01, d = .35), externalizing symptoms (p < .05, d = .21), attention problems (p < .01, d = .32) and children’s rumination (p < .05, d = .44).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis explored the effect of parenting interventions that include self-compassion components on parental self-compassion and parent and child outcomes. Thirteen studies were identified including five RCTs and eight repeated-measures studies. There was a high degree of variability in the parenting populations included across the studies and the types of interventions and self-compassion-promoting components that were utilized. Almost three-quarters of the studies were mindfulness-based interventions, and only three were specific compassion-based interventions. All but two of the studies measured parental self-compassion outcomes with a version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003b) and five utilized an unpublished brief measure of self-compassion.

Results indicated that parenting interventions that included self-compassion components significantly increased parental self-compassion of small to moderate effect from pre- to post-intervention and of moderate effect between groups. Findings also indicated that these effects were maintained or increased further over time. There was evidence of publication bias in the pre-post analysis in favour of studies with positive outcomes. Accounting for this reduced the moderate pooled effect size (g = 0.372) to a small effect (g = 0.224). One exception was Mendelson et al. (2018) who returned a small negative effect size. This result is interesting as no particular characteristics about this study were identified in our review that markedly differentiate it from population, methodological or intervention characteristics of other studies.

Results related to our secondary aims indicated that parenting interventions that included self-compassion components were effective at improving parental outcomes with small to moderate effects from pre-post intervention, including depression symptoms (g = − 0.425), anxiety symptoms (g = − 0.377), stress symptoms (g = − 0.363) and mindfulness scores (g = 0.483). There were mixed results for between-group and follow-up effects on parent outcomes of no to large effects.

Four studies (Jones et al. 2018; Potharst et al. 2017; Potharst et al. 2018; Ridderinkhof et al. 2018) assessed the effects of the intervention on a range of child behaviour outcomes. Three of these found evidence of improvements in child outcomes at post-intervention on at least one child-outcome variable, and most of these effects were maintained or increased at follow-up.

Effect on Self-Compassion

The pooled effect size for pre-post analyses was smaller than found in previous studies, which indicated large increases in self-compassion from participating in self-compassion interventions (Neff and Germer 2013; Smeets et al. 2014). This may be explained by the fact that the majority of interventions included were mostly comprised of mindfulness components and few other types of self-compassion-promoting components. The finding that there was only publication bias evident for the pre-post analysis for self-compassion suggests that publication bias may be a greater issue for the other variables than was detected. This is because self-compassion was frequently one of many outcome measures included in these studies, so it would be unusual for publication bias to affect only this variable, and our quantitative analyses had limited power to detect publication bias due to the smaller number of studies included (Macaskill et al. 2001).

Effect on Parent Outcomes

The findings that the interventions decreased parental depression and anxiety are consistent with findings from previous research that self-compassion interventions are effective at reducing depression, anxiety and stress scores in the general population (Neff and Germer 2013). Mindfulness-based parenting interventions have also been shown to reduce parental depression, anxiety and stress (Alexander 2018), so the degree to which the different self-compassion-promoting components contribute to the observed effects is unclear. The effect sizes observed are also similar to those found for the effect of more traditional parenting interventions on depression and anxiety (Benzies et al. 2013). The findings that the post-intervention effects for parental outcomes were maintained over time is consistent with previous meta-analytic research that found that the effects of mindfulness interventions were maintained at 12-month follow-ups (Hofmann et al. 2010). The findings that these effects frequently increased significantly over time may be explained by the fact that these interventions target parent-child relationships, which are reciprocal and cumulative in nature (Edwards 2002; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007).

Effect on Child Outcomes

The results that the interventions had some benefit on child outcomes is consistent with previous research showing that mindfulness-based parenting programs improve child outcomes (Neece 2014; Singh et al. 2006; Singh et al. 2007).

Limitations and Future Research

A major limitation of our findings is the relatively small number of studies that met inclusion criteria for our review. This, in combination with limited assessment of study level predictors and moderators of treatment effectiveness across studies, suggests that our findings might best be taken as preliminary evidence for the effects of parenting interventions that include self-compassion-promoting components. We recognize additional limitations in our search strategy such as limiting our search to studies published in the English language. This, together with our unsuccessful attempts to identify grey literature, suggests that we may have failed to identify studies that met our eligibility criteria and, in particular, were from non-western or developing countries. As studies were predominantly from first-world countries (e.g. Australia, the UK and the Netherlands), findings may not be representative of global populations. It is likely that parenting interventions will continue to include self-compassion-promoting components in the future. Thus, in order to further clarify the benefit of including such components, we encourage future studies to include quantitative measures of self-compassion, common parenting outcome measures and measures of child social, emotional and behavioural functioning. Future studies should also aim to increase the quality and explanatory power of research in this area by including larger sample sizes, comparison groups, undertaking assessment of study level predictors and moderators of treatment effectiveness and improving methodological issues that may contribute bias. Importantly, in the current context, it remains unclear to what extent specific treatment components contributed to the observed effects and further research is indicated to further elucidate the comparative effectiveness of the distinct self-compassion-promoting components on parental and child outcomes.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting stress index/short form. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting Stress Index (3rd ed.). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, Burlington, VT, www.aseba.org.

Alexander, K. (2018). Integrative review of the relationship between mindfulness-based parenting interventions and depression symptoms in parents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 47(2), 184–190.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publishers.

Arnold, D. S., O’Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S., & Acker, M. M. (1993). The Parenting Scale: a measure of dysfunctional parenting indiscipline situations. Psychological Assessment, 5, 137–144.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342.

Bardacke, N. (2012). Mindful birthing: training the mind, body, and heart for childbirth and beyond. Harper Collins.

Beck, A. T., & Beck, R. W. (1972). Screening depressed patients in family practice: A rapid technique. Postgraduate Medicine, 52(6), 81–85

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Manual for the Beck anxiety inventory. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). Beck depression inventory (BDI). Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571.

Beer, M., Ward, L., & Moar, K. (2013). The relationship between mindful parenting and distress in parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Mindfulness, 4(2), 102–112.

Benzies, K. M., Magill-Evans, J. E., Hayden, K. A., & Ballantyne, M. (2013). Key components of early intervention programs for preterm infants and their parents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(S1), S10.

Birnie, K., Speca, M., & Carlson, L. E. (2010). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health, 26(5), 359–371.

Bögels, S. M., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S., Römer, M., & van der Meulen, R. (2014). Mindful parenting in mental health care: effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness, 5(5), 536–551.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., et al. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42, 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007.

Bora, E., Akdede, B. B., & Alptekin, K. (2017). The relationship between cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 1030–1040.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. R. (2005). Comprehensive meta-analysis version 3. Englewood: Biostat.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 97–111.

Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(9), 1133–1143.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Berrena, E., Bamberger, K. T., Loeschinger, D., Greenberg, M. T., & Nix, R. L. (2014). The Mindfulness-enhanced Strengthening Families Program: integrating brief mindfulness activities and parent training within an evidence-based prevention program. New Directions for Youth Development, 142, 45–58.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786.

De Bruin, E. I., Sieh, D. S., Zijlstra, B. J., & Meijer, A. M. (2018). Chronic childhood stress: Psychometric properties of the Chronic Stress Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (CSQ-CA) in three independent samples. Child Indicators Research, 11, 1389–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9478-3.

de Bruin, E. I., Topper, M., Muskens, J. G., Bögels, S. M., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) in a meditating and a non-meditating sample. Assessment, 19(2), 187–197.

de Bruin, E. I., Zijlstra, B. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). The meaning of mindfulness in children and adolescents: further validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) in two independent samples from the Netherlands. Mindfulness, 5(4), 422–430.

Derogatis, L. R. (1992). Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring and procedures manual (3rd ed.). Minneapolis: National Computer Systems.

Dienen, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of personality assessment, 49(1), 71-75.

Duncan, L. G. (2007). Assessment of mindful parenting among parents of early adolescents: Development and validation of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting scale. PhD Dissertation, Pennsylvania State University.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95(449), 89–98.

Edwards, M. E. (2002). Attachment, mastery, and interdependence: a model of parenting processes. Family Process, 41(3), 389–404.

Farkas-Klein, C. (2008). Parental Evaluation Scale (EEP): Development, psychometric properties and applications. Universitas Psychologica, 7, 457–467.

Felder, J. N., Lemon, E., Shea, K., Kripke, K., & Dimidjian, S. (2016). Role of self-compassion in psychological well-being among perinatal women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(4), 687–690.

Fonseca, A., & Canavarro, M. C. (2018). Exploring the paths between dysfunctional attitudes towards motherhood and postpartum depressive symptoms: the moderating role of self-compassion. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(1), e96–e106.

Fossum, S., Handegård, B. H., Martinussen, M., & Mørch, W. T. (2008). Psychosocial interventions for disruptive and aggressive behaviour in children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17(7), 438–451.

Friedrich, W. N., Greenberg, M. T., & Crnic, K. (1983). A short-form of the Questionnaire on Resources and Stress. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 88(1), 41–48.

Furlong, M., McGilloway, S., Bywater, T., Hutchings, J., Smith, S. M., & Donnelly, M. (2013). Cochrane review: behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(2), 318–692.

Germer, C. K. (2009a). The mindful path to self-compassion: Freeing yourself from destructive thoughts and emotions. New York: Guilford Press.

Germer, C. K. (2009b). The mindful path to self-compassion: Freeing yourself from destructive thoughts and emotions. The Guilford Press.

Germer, C. K. (2012). Cultivating compassion in psychotherapy. In C. Germer & R. Siegel (Eds.), Wisdom and compassion in psychotherapy: Deepening mindfulness in clinical practice (pp. 93–110). New York: Guilford.

Gilbert, P. (2000). Social mentalities: Internal ‘social’ conflicts and the role of inner warmth and compassion in cognitive therapy. In P. Gilbert & Bailey K.G (eds.), Genes on the Couch: Explorations in evolutionary psychotherapy (p. 118-150). Hove: Psychology Press.

Gilbert, P. (2010a). Compassion focused therapy: The CBT distinctive features series. London: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2010b). Compassion focused therapy: The CBT distinctive features series. London: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2010c). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life's challenges. New Harbinger Publications.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41.

Gilbert, P. (2015). Affiliative and prosocial motives and emotions in mental health. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 381–389.

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N. V., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504772812959.

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self‐report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 239–255.

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586.

Goodman, J. H., Guarino, A., Chenausky, K., Klein, L., Prager, J., Petersen, R., Forget, A., & Freeman, M. (2014). CALM Pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 17(5), 373–387.

Gorman, L. L., O'Hara, M. W., Figueiredo, B., Hayes, S., Jacquemain, F., Kammerer, M. H., Klier, C. M., Rosi, S., Seneviratne, G., & Sutter-Dallay, A. L. (2004). Adaptation of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV disorders for assessing depression in women during pregnancy and post-partum across countries and cultures. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(46), 17–23.

Goss, K., Gilbert, P., & Allan, S. (1994). An exploration of shame measures - I: The Other as Shamer Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 17(5), 713–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X.

Gouveia, M. J., Carona, C., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2016). Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: the mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 7(3), 700–712.

Hájos, N., Karlócai, M. R., Németh, B., Ulbert, I., Monyer, H., Szabó, G., et al. (2013). Input-output features of anatomically identified CA3 neurons during hippocampal sharp wave/ripple oscillation in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(28), 11677–11691.

Hartling, L., Hamm, M., Milne, A., Vandermeer, B., Santaguida, P. L., Ansari, M., Tsertsvadze, A., Hempel, S., Shekelle, P., & Dryden, D. M. (2012). Validity and inter-rater reliability testing of quality assessment instruments. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10021-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC039-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665.

Hayes-Skelton, S. A., Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2013). A randomized clinical trial comparing an acceptance-based behavior therapy to applied relaxation for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032871.

Hedges, L., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical models for meta-analysis. New York: Academic Press.

Higgins, J. & Green, S., (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 31 May 2019.

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557.

Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169.

Jones, L., Hastings, R. P., Totsika, V., Keane, L., & Ruhle, N. (2014). Child behavior problems and parental well-being in families of children with Autism: the mediating role of mindfulness and acceptance. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 119(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-119.2.171.

Jones, L., Gold, E., Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Jones, M., Griffiths, A., & Silverton, S. (2018). A mindfulness parent well-being course: evaluation of outcomes for parents of children with autism and related disabilities recruited through special schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(1), 16–30.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: the program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York: Dell Publishing.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alhamzawi, A. O., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., & Benjet, C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385.

Kim, S. Y., Park, J. E., Lee, Y. J., Seo, H. J., Sheen, S. S., Hahn, S., Jang, B. H., & Son, H. J. (2013). Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66(4), 408–414.

Kirby, J. N., & Baldwin, S. (2018). A randomized micro-trial of a loving-kindness meditation to help parents respond to difficult child behavior vignettes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(5), 1614–1628.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Leff, E. W., Jefferis, S. C., & Gagne, M. P. (1994). The development of the maternal breastfeeding evaluation scale. Journal of Human Lactation, 10(2), 105–111.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., Pickles, A., & Rutter, M. (2000). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, (ADOS-2), Part 1:Modules 1–4 (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Löwe, B., Wahl, I., Rose, M., Spitzer, C., Glaesmer, H., Wingenfeld, K., et al. (2010). A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(1-2), 86–95.

Luberto, C. M., Park, E. R., & Goodman, J. H. (2017). Postpartum outcomes and formal mindfulness practice in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal women. Mindfulness, 9(3), 850–859.

Luthar, S. S., & Suchman, N. E. (2000). Relational Psychotherapy Mothers' Group: a developmentally informed intervention for at-risk mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 12(2), 235–253.

Luthar, S. S., Suchman, N. E., & Altomare, M. (2007). Relational Psychotherapy Mothers' Group: a randomized clinical trial for substance abusing mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 19(1), 243–261.

Luthar, S. S., Curlee, A., Tye, S. J., Engelman, J. C., & Stonnington, C. M. (2017). Fostering resilience among mothers under stress: “Authentic Connections Groups” for medical professionals. Women’s Health Issues, 27(3), 382–390.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155.

Macaskill, P., Walter, S. D., & Irwig, L. (2001). A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 20(4), 641–654.

MacDonald, E. E., Hastings, R. P., & Fitzsimons, E. (2010). Psychological acceptance mediates the impact of the behaviour problems of children with intellectual disability on fathers' psychological adjustment. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00546.x.

Majdandžić, M., de Vente, W., & Bögels, S. M. (2016). Challenging parenting behavior from infancy to toddlerhood: Etiology, measurement and differences between fathers and mothers. Infancy, 21(4), 423–452.

Mann, J., Kuyken, W., O’Mahen, H., Ukoumunne, O. C., Evans, A., & Ford, T. (2016). Manual development and pilot randomised controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus usual care for parents with a history of depression. Mindfulness, 7(5), 1024–1033.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., Leiter, M. P., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schwab, R. L. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

McCue Horwitz, S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Storfer-Isser, A., & Carter, A. S. (2007). Prevalence, correlates, and persistence of maternal depression. Journal of Women's Health, 16(5), 678–691.

Mendelson, T., McAfee, C., Damian, A. J., Brar, A., Donohue, P., & Sibinga, E. (2018). A mindfulness intervention to reduce maternal distress in neonatal intensive care: a mixed methods pilot study. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 21(6), 791–799.

Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guildford Press.

Mitchell, A. E., Whittingham, K., Steindl, S., & Kirby, J. (2018). Feasibility and acceptability of a brief online self-compassion intervention for mothers of infants. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(5), 553–561.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The, P. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269.

Moreira, H., Gouveia, M. J., Carona, C., Silva, N., & Canavarro, M. C. (2015). Maternal attachment and children’s quality of life: the mediating role of self-compassion and parenting stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2332–2344.

Moreira, H., Carona, C., Silva, N., Nunes, J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2016). Exploring the link between maternal attachment-related anxiety and avoidance and mindful parenting: The mediating role of self-compassion. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 89(4), 369–384.

Neece, C. L. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 174–186.

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102.

Neff, K. (2003a). Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion: stop beating yourself up and leave insecurity behind. New York: HarperCollins.

Neff, K. D. (2012). The science of self-compassion. In C. Germer & R. Siegel (Eds.), Compassion and wisdom in psychotherapy (pp. 79–92). New York: Guilford Press.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44.

Neff, K. D., Long, P., Knox, M. C., Davidson, O., Kuchar, A., Costigan, A., Williamson, Z., Rohleder, N., Tóth-Király, I., & Breines, J. G. (2018). The forest and the trees: examining the association of self-compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self and Identity, 17(6), 627–645.

Noens, I., De la Marche, W., & Scholte, E. (2012). SRS-A. Screeningslijst voor autismespectrumstoornissen bij volwassenen. Handleiding. Amsterdam: Hogrefe Uitgevers.

Orsillo, S. M., & Roemer, L. (2011). The mindful way through anxiety: Break free from chronic worry and reclaim your life. Guilford Press.

Perez-Blasco, J., Viguer, P., & Rodrigo, M. F. (2013). Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on psychological distress, well-being, and maternal self-efficacy in breast-feeding mothers: results of a pilot study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(3), 227–236.

Pit-ten Cate, I. (2003). Positive gain in mothers of children with physical disabilities. Doctoral thesis: University of Southhampton, England, UK.

Pommier, E. A. (2011). The Compassion Scale. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 72(4-A), 1174.

Potharst, E. S., Aktar, E., Rexwinkel, M., Rigterink, M., & Bögels, S. M. (2017). Mindful with your baby: feasibility, acceptability, and effects of a mindful parenting group training for mothers and their babies in a mental health context. Mindfulness, 8(5), 1236–1250.

Potharst, E. S., Zeegers, M., & Bögels, S. M. (2018). Mindful with your toddler group training: feasibility, acceptability, and effects on subjective and objective measures. Mindfulness, 1–15.

Psychogiou, L., Legge, K., Parry, E., Mann, J., Nath, S., Ford, T., & Kuyken, W. (2016). Self-compassion and parenting in mothers and fathers with depression. Mindfulness, 7(4), 896–908.

Putnam, S. P., Helbig, A. L., Gartstein, M. A., Rothbart, M. K., & Leerkes, E. (2014). Development and assessment of short and very short forms of the infant behavior questionnaire– revised. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96, 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.841171.

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255.

Raes, F., Hermans, D., de Decker, A., Eelen, P., & Williams, J. M. G. (2003). Autobiographical memory specificity and affect regulation: an experimental approach. Emotion, 3(2), 201–206.

Ridderinkhof, A., de Bruin, E. I., Blom, R., & Bögels, S. M. (2018). Mindfulness-based program for children with autism spectrum disorder and their parents: direct and long-term improvements. Mindfulness, 9(3), 773–791.

Roemer, L., Orsillo, S. M., & Salters-Pedneault, K. (2008). Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 1083–1089.

Roeyers, H., Thys, M., Druart, C., De Schryver, M., & Schittekatte, M. S. R. S. (2011). SRS Screeningslijst voor autismespectrumstoornissen. Amsterdam: Hogrefe.

Salzberg, S. (2009). Foreword. In C. K. Germer (Ed.), The mindful path to self-compassion. Guilford: New York.

Sawyer, M. G., Arney, F. M., Baghurst, P. A., Clark, J. J., Graetz, B. W., Kosky, R. J., Nurcombe, B., Patton, G. C., Prior, M. R., Raphael, B., & Rey, J. M. (2001). The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35(6), 806–814.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. a new approach to preventing relapse. Nueva York: Guilford.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M., & Teasdale, J. D. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P): elaboration and explanation. British Medical Journal, 349, 7647.

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, H., et al. (1997). The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry, 5, 232–241.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S., Fisher, B. C., Wahler, R. G., Mcaleavey, K., Singh, J., & Sabaawi, M. (2006). Mindful parenting decreases aggression, noncompliance, and self-injury in children with autism. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14(3), 169–177.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S., Singh, J., Curtis, W. J., Wahler, R. G., & McAleavey, K. M. (2007). Mindful parenting decreases aggression and increases social behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification, 31(6), 749–771.

Sirois, F. M., Bögels, S., & Emerson, L. (2018). Self-compassion improves parental well-being in response to challenging parenting events. The Journal of Psychology, 153(3), 327–341.

Smeets, E., Neff, K., Alberts, H., & Peters, M. (2014). Meeting suffering with kindness: effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for female college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(9), 794–807.

Somerville, S., Dedman, K., Hagan, R., Oxnam, E., Wettinger, M., Byrne, S., et al. (2014). The perinatal anxiety screening scale: development and preliminary validation. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 17(5), 443–454.

Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D. A., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1984). Vineland: adaptive behavior scales: Interview edition, expanded form. American Guidance Service.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

Taylor, B. L., Cavanagh, K., & Strauss, C. (2016). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in the perinatal period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11(5).

Townshend, K., Jordan, Z., Stephenson, M., & Tsey, K. (2016). The effectiveness of mindful parenting programs in promoting parents’ and children's wellbeing: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 14(3), 139–180.

Townshend, K., Caltabiano, N. J., Powrie, R., & O’Grady, H. (2018). A preliminary study investigating the effectiveness of the Caring for Body and Mind in Pregnancy (CBMP) in reducing perinatal depression, anxiety and stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(5), 1556–1566.

Treanor, M., Erisman, S. M., Salters‐Pedneault, K., Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2011). Acceptance‐based behavioral therapy for GAD: Effects on outcomes from three theoretical models. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 127–136.

Ussher, M., Patten, C. A., Bronars, C., Vickers Douglas, K., Levine, J., Tye, S. J., et al. (2017). Supervised, vigorous intensity exercise intervention for depressed female smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(1), 77–86.

Veerman, J. W., Janssen, J., Kroes, G., De Meyer, R., Nguyen, L., & Vermulst, A. (2012). Vragenlijst Gezinsfunctioneren volgens Ouders (VGFO). Nijmegen: Praktikon.

Verhulst, F. C., & Van der Ende, J. (2013a). Handleiding ASEBA-Vragenlijsten voor leeftijden 6 t/m 18 jaar: CBCL/6-18. Rotterdam: YSR en TRF, ASEBA.

Verhulst, F. C., & Van der Ende, J. (2013b). Handleiding ASEBA-Vragenlijsten voor leeftijden 6 t/m 18 jaar: CBCL/6-18. YSR en TRF, ASEBA, Rotterdam.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/00223514.54.6.1063.

Weiss, D. S. (2007). The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In J. P. Wilson & C. S.-K. Tang (Eds.), International and cultural psychology. Crosscultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 219–238). Springer.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FJ: designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses and wrote the paper. AS: collaborated with the study design. JM: collaborated with the design of the study, assisted with the data analyses and editing the final manuscript and responded to reviewer’s comments as corresponding author. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Each of the studies included in the review received appropriate ethical approvals.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jefferson, F.A., Shires, A. & McAloon, J. Parenting Self-compassion: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness 11, 2067–2088 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01401-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01401-x