Abstract

Parenting preschoolers can be a challenging endeavor. Yet anecdotal observations indicate that parents who are more mindful may have greater ease in contending with the emotional demands of parenting than parents who are less mindful. Therefore, we hypothesized that parenting effort, defined as the energy involved in deciding on the most effective way to respond to a preschooler, would be negatively associated with mothers’ mindfulness. In this study, a new parenting effort scale and an established mindfulness scale were distributed to 50 mothers of preschoolers. Using exploratory factor analysis, the factor structure of the new parenting effort scale was examined and the scale was refined. Bivariate correlations were then conducted on this new Parenting Effort—Preschool scale and the established mindfulness scale. Results confirmed the hypothesis that a negative correlation exists between these two variables. Implications are that mindfulness practices may have the potential to alleviate some of the challenges of parenting preschoolers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents of preschoolers have the challenging task of creating a safe and secure environment for their child, while at the same time providing ample breadth for the developmentally appropriate tasks of exploration, investigation, and experimentation. The preschool child is expected to learn the rudimentary skills of socialization, which usually include not having her desires fulfilled at will. This often leads to frustration on the child’s part and calls for steadiness and consistency in discipline on the part of the parent. As the parent is inevitably emotionally linked to the child’s emotional state, remaining consistent in discipline can be an enormous challenge for her. In addition, parents and their children often develop an automaticity in their interactions, or habitual patterns of behavior with each other (Dumas 2005). Interrupting these habitual and often maladaptive behavior patterns and then engaging in the mental deliberations necessary to decide on the most effective way to respond to the child can require an appreciable amount of emotional effort and be tremendously stressful. One path to decreasing this stress and alleviating this parental dilemma calls for an attuned awareness of one’s thoughts, emotional state, and interactions in the moment that they are occurring.

Mindfulness is a mental state in which one actively engages in “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgementally” (Kabat-Zinn 1994, p. 4). Through mindfulness practice, one becomes increasingly aware of one’s thought and emotional processes as they unfold, in this case, as they occur in response to a child’s actions. The ability to “pause” before providing a habitual reaction becomes an available option, and responding to the child occurs only after taking ample time to consider the array of possible ways to react. Singh and colleagues (2010) speculated that mindful parenting would reduce the amount of effort required in parenting. They posited that “As caregivers increase their mindfulness, they may become more responsive to each moment of their interactions with the individuals in their care. Developing calm acceptance of whatever behaviors are exhibited, without attempting to impose their will on the situation, minimizes the amount of energy used and the build-up of any resistance” (Singh et al. 2010, p. 173). Bluth and Wahler (2011) confirmed this by finding a negative linear relationship between effort expended by parents of adolescents and parent mindfulness. This study hypothesizes that the same negative correlation exists between parenting effort of parents of preschoolers and parent mindfulness levels, and in so doing seeks to further validate the evidence found in the previous study. In order to investigate this hypothesis, we first developed a parenting effort scale specific to parents of preschoolers, and we then explored the association between mothers’ perceptions of their parenting effort and mothers’ perceptions of their level of mindfulness.

Method

Participants

Fifty mothers of preschoolers volunteered to participate in this study following approval from the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board. A majority of the mothers were married and well educated; race/ethnicity was as follows: 82% White, 14% Asian, 2% Black, and 2% Hispanic. Ages of parents ranged from 20 to 60, and the mean number of children in the household was 1.8. Household income ranged significantly, from under $50,000 to $200,000 annually; the mean was between $75,000 and $125,000. The gender of preschoolers was 50% female, 48% male, with one participant (2%) not providing data.

Measures

Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (Brown and Ryan 2003)

This scale addresses “attention to and awareness of what is occurring in the present” (Brown and Ryan 2003 p. 824). The 15 items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. This scale has been reported to yield alpha coefficients for everyday mindfulness for college students and adults to be .80 and .87, respectively (Brown and Ryan 2003). The alpha coefficient for our sample of preschool mothers is .92.

Parenting Effort Scale—Preschool (PES-PS)

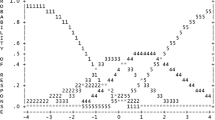

The original 15-item scale developed by Bluth, Williams, and Wahler (2010) was distributed to participants in this study. These original items were initially created from mothers’ descriptions of situations in daily interactions with their children that demanded high and low amounts of parenting effort; the items were then translated into items for the scale. Examples of items are “I am often indecisive when my child opposes my instructions” and “I find it hard to think when my child is upset.” A 5-point Likert-type scale was used which ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” To investigate the factor structure of the scale, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2004). Six items were dismissed either because they did not load with values of 0.40 or higher or because they loaded equally on more than one factor. The remaining nine items loaded on one factor. This factor describes the kind of parenting effort that taxes parents emotionally; it reflects the struggles parents have of staying centered in the midst of handling the various types of challenging parenting situations frequently found in interactions between parents and their preschool children. Parents have claimed that they would like to discipline in a manner more in line with their values rather than reacting emotionally in the moment (Duncan et al. 2009); the type of parenting effort assessed by this scale (Appendix A) taps the difficulty demonstrated in this dimension of parenting. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .68.

Results

Descriptive Data

Results of the descriptive analysis for the mindfulness measure for mothers of preschoolers in our sample are relatively high at M = 4.17, SD = .92. This is slightly less than that reported by Brown and Ryan (2003) of Zen practitioners (M = 4.29, SD = 0.66) and greater than that reported in the same study with a sample of adults (M = 3.97, SD = .64).

Based on the newly developed measure for the kind of parenting effort specific to mothers of preschoolers (PES-PS), results indicated that mothers’ perceptions ranged widely from 9 to 29; M = 18.52, SD = 4.51.

Bivariate Correlations

Bivariate correlation analysis was conducted; Pearson product–moment correlations between parenting effort and parent mindfulness resulted in r = −0.512. This negative correlation indicates that when mothers’ perceptions of their mindfulness increased, the amount of parenting effort they felt was required in parenting their preschoolers decreased.

Discussion

The parenting effort scale introduced here has been constructed to operationalize the aspect of parenting that encompasses the emotional challenges of interacting with and relating to one’s child while maintaining a sense of perspective and objectivity. The challenge inherent here is in its obvious contradiction; parents are by definition inescapably emotionally entwined with their child, yet in order to discipline consistently and effectively, parents must maintain a certain level of objectivity and emotional detachment. The parenting effort construct provided here attempts to capture the essence of this dilemma. For example, one of the nine items in the scale reads, “I am often indecisive when my child opposes my instructions.” One can imagine a situation where a parent has issued a request to her preschool child, and the child is not complying. The parent now struggles with the dilemma: Do I put my foot down and issue a consequence, as the behaviorists might suggest, and risk escalating the negativity of the situation, possibly resulting in a full-blown tantrum? Is the request really worth the energy investment it will take with no guarantee of a positive outcome? One can imagine the parent weighing the pros and cons of various responses, mentally debating the potential effect of her response. The parenting effort scale created here measures the stress encountered in these kinds of dilemmas and the effort expended in contending with them.

In this study, parenting effort has been shown to negatively correlate with mindfulness, further confirming the prediction of Singh and colleagues (2010) and the results of an earlier study which explored these same variables with parents of adolescents (Bluth and Wahler 2011). Keeping in mind that the aspect of mindfulness that this scale addresses is that of attentiveness in the moment, a possible interpretation of these results is that as a mother’s attention and awareness to her habitual interactions with her child increases, the effort expended in understanding, determining, and responding to the needs of the child decreases, possibly because the level of effort necessary at that moment is no longer essential. Parents who are more mindful therefore expend less energy in their attempts to meet the needs of the child. It is important to note here that a decrease in parenting effort does not imply either parental neglect or permissiveness; mindfulness, as defined by this scale, encompasses awareness and attentiveness in the present moment. A mindful parent, therefore, would necessarily be one who was well aware of her child’s emotional states and needs.

However, this is not the only possible interpretation of these results. It is possible that mothers who are more mindful are also not as bothered or concerned about their child’s behavior, particularly in relation to how it may be perceived by others, possibly because they see the child’s “acting out” as part of her developmental process and not as a reflection of their mothering. For this reason, these more mindful mothers perceive the effort that they expend in parenting as less than that of mothers who are less mindful, who may be more disturbed by their preschooler’s problematic behavior. However, at this point it is important to take a step back to fully recall the essence of the concept of mindfulness; it is not about being emotionally detached from a situation or interaction; rather, it is centered on the idea of being fully present to a given situation, including traversing the emotions, sensations, and interactions taking place in the moment, and doing so with clear objectivity and equanimity. Given this definition then, mindful mothers would be acutely attuned to the emotional needs of their preschoolers, and would not be dismissive in the instance that their needs were not being met. Therefore, although mindful mothers might be less reactive to problematic child behavior, it is unlikely that they would attribute all problematic child behavior to a developmental stage.

Recognizing that the relationship between parent mindfulness and parenting effort is not a causal one, we cannot ascribe or assume a direction to the manner in which the two variables interact. Therefore, we can offer an alternative explanation in which the level of parenting effort influences the level of mindfulness of the parent. For example, it is conceivable that high parenting effort impacts mindfulness in such a way that parents who expend greater emotional energy when engaged in parenting dilemmas have greater difficulty being mindful, possibly because they are distracted by their concerns about being a “good” parent. However, this relationship is unlikely since it is possible to be mindful in the midst of a chaotic or emotionally charged situation. Therefore, bringing mindfulness to a chaotic event would most likely interrupt and de-escalate the emotionally charged situation.

Having considered alternative explanations for the correlation between our two variables, we find ourselves returning to our original explanation. As parents become more mindful, they develop greater awareness of the habitual patterns of interaction between themselves and their preschoolers. The automaticity (Dumas 2005) of engagement is broken, and parents have the opportunity to alter these patterns of behavior. Once a less reactive, more nuanced, and emotionally neutral response is chosen, the amount of effort needed to parent is lessened. Hence, it is possible that an increase in parental mindfulness may lead to a decrease in parenting effort.

These results imply that parents of preschoolers may potentially be able to lessen the demands on their role as parents and decrease their parenting effort by becoming more mindful. Parental mindfulness can be developed through engaging in various stand-alone mindfulness programs such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn 1990) or parenting programs that encompass mindfulness techniques (Coatsworth et al. 2009).

There are several limitations to this study. First, in order to assert a causal relationship between parent mindfulness and parenting effort, it is essential to assess these variables at different time points to establish the temporal order of the variables. Until temporal order is determined, we can state only that there is a negative association between the variables. Second, further studies should be conducted with larger samples to confirm these results.

In conclusion, these findings show a clear negative correlation between parenting effort and parent mindfulness. If causality can be established in future studies, there is a promise for the ability of mindfulness interventions to decrease the effort required in parenting preschoolers.

References

Bluth, K., & Wahler, R. (2011). Does effort matter in mindful parenting? Mindfulness, 2, 175–178, doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0056-3.

Bluth, K., Williams, K. L., & Wahler, R. (2010). Parenting effort scale. Unpublished scale. Psychology. University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Knoxville.

Brown, K., & Ryan, R. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Greenberg, M. T., & Nix, R. L. (2009). Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their youth: Results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 203–217. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8.

Dumas, J. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. New York: Random House.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2004). MPlus user’s guide (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Author.

Singh, N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., Singh, A. N., Adkins, A. D., et al. (2010). Training in mindful caregiving transfers to parent–child interactions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 167–174. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9267-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Parenting Effort Scale—Preschool (PES-PS)

-

1.

I find it hard to think when my child is upset.

-

2.

Listening to my child’s view of a problem comes easy for me.

-

3.

When I see the look on my child’s face, I can usually figure out what it means.

-

4.

I am often indecisive when my child opposes my instructions.

-

5.

When my child comes home from school, it takes time for me to reconnect to her/him.

-

6.

Parenting my child takes up more time than it should.

-

7.

When my child starts talking to me, I immediately know what’s on her/his mind.

-

8.

I keep wondering what my child thinks about me.

-

9.

When my child and I have an argument it’s hard for me to get back on track as a parent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bluth, K., Wahler, R.G. Parenting Preschoolers: Can Mindfulness Help?. Mindfulness 2, 282–285 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0071-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0071-4