Abstract

Mindfulness is defined as moment-by-moment social awareness derived from a non-judgmental, friendly, and receptive attitude. Previous research suggested that mindfulness has a positive effect on parenting. The present study examined the association between mindfulness, parent–child relationship, and child social behavior in a Chinese sample. Two-hundred and sixteen mothers with children of preschool age completed a set of questionnaires on their mindfulness, parent–child relationships, and their children’s social behavior. A path analysis of their responses indicated that mindfulness had a significant and positive effect on the mother-child relationship in terms of attachment, involvement, and parental confidence and a negative effect on discipline practice and relational frustration. Mindfulness also had a significantly negative indirect effect on children’s emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems and a significant and positive indirect effect on children’s prosocial behavior. These results supported previous findings that mindful parents were more involved in their children’s lives and have a tendency to be more aware of their children’s needs. Implications of these results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mindfulness involves focusing one’s attention on the present moment in a non-judgmental and accepting way (Kabat-Zinn 1994, 2003). In recent years, the internal process of mindfulness has been extended to inter-personal interaction such as in the parent–child relationship (e.g., Altmaier and Maloney 2007; Bögels and Restifo 2014). Mindful parenting was defined as paying attention to the present moment and expressing acceptance, kindness, and compassion during the parenting process (Kabat-Zinn and Kabat-Zinn 1997). Fostering mindfulness in parenting is one avenue for improving the effectiveness of parenting interventions (Dumas 2005). Research has shown the promising effects of mindfulness on parent–child relationships, reduction of child problem behavior, and decreased parental stress in cases of children with development problems (e.g., van der Oord et al. 2012; Parent et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2009). Despite the evidence indicating that parental mindfulness can enhance children’s positive social behavior and decrease their aggressive behavior (e.g., Singh et al. 2007, 2009), research on the mechanism underlying the effects of parental mindfulness is limited.

Researchers have proposed a mindfulness model with two components: (1) self-regulation of attention, which refers to non-judgmental awareness of sensations, thoughts, and feelings in the present moment in the “beginner’s mind,” and (2) adoption of attitudes, which is characterized by curiosity, openness, and acceptance toward one’s experience (Bishop et al. 2004). To the social context of parent–child relationship, Duncan et al. (2009) specially developed a five-dimensional model including listening to children with full attention, emotional awareness of self and child, self-regulation and less reactive in parenting, non-judgmental acceptance of self and child, and compassion for self and child. These models can be used to elaborate the influences of parents’ mindfulness on different aspects of the parent–child relationship such as attachment, relational frustration, discipline practice, involvement, and parenting self-efficacy.

Regulating attention is the core aspect of mindfulness which helps parents focus on the present moment, paying more attention to children’s activities and needs. It can promote secure attachment relationships and affect child’s social interactions with others (Hertz et al. 2014). Because an individual interacts with others according to his or her own “internal working model,” which is developed with a primary caregiver, more attention and sensitivity of parents are important to build a positive internal representation of to a child (Bowlby 1982; Ainsworth 1989). What is more, mindfulness helps parents distance themselves from their own dysfunctional attachment styles and negative emotions. The awareness of own attachment system helps parents to build a health attachment relationship with their children and avoid transferring their own dysfunctional attachment styles to the next generation. This awareness is what defines mindfulness, and it can help individuals recognize the here-and-now experience of being together with others (Kabat-Zinn 2003).

Parents inevitably encounter challenges in the course of parenting. Parents who experience frustration with their parent–child relationship are more likely to report child emotional symptoms, hyperactivity, and peer problems (Rudd et al. 1998). Research has found that mindfulness was positively associated with parental satisfaction and negatively associated with parental frustration (e.g., Dawe and Harnett 2007; Singh et al. 2009). Mindful parenting was also associated with reductions in parenting stress, depression, and anxiety (Geurtzen et al. 2015). Mindful individuals can adopt a here-and-now attitude and are less likely to ruminate on negative experiences. Dumas (2005) found that mindful parents can distance themselves from negative parenting experiences and can observe and describe negative parenting experiences as individual cases without personalizing them or blaming themselves (Baer and Krietemeyer 2006). They pause before reacting to negative affection, disengage from an automatic thought, and focus on the present moment (Bishop et al. 2004). This distance allows parents to effectively control and regulate their own emotions and then select a rational parenting practice (Duncan et al. 2009). Moreover, with high level of mindfulness, parents can not only regulate their emotion more effectively but they can also teach their children how to be aware of and regulate emotion, which in turn can promote children’s social adjustment and skills (Duncan et al. 2009).

Another important aspect of mindful parenting is the attitude of acceptance and compassion. Self-compassion can cultivate parents’ kindness toward themselves, and then, the compassion is extended to their children, resulting in greater relationship satisfaction (Bögels et al. 2010). Compassion helps parents develop a sense of common humanity which promotes parents’ understanding and love toward children (Neff 2003). Compassion for children allows parents to choose less harsh and discipline practice; instead, more acceptance and forgiving are given toward the children. Parental discipline was associated with children’s problem behavior and emotional problems (Larzelere 2000). Shapiro and White (2014) proposed the integration of Buddhist philosophy into child discipline. Disagreeing with both authoritarian and permissive parenting styles, they recommended a dialectical “authoritative” parenting style in which parents demonstrate unconditional love for their children, support child autonomy and competence development, and maintain appropriate authority in the face of a child’s misbehavior. Mindful parents may provide a safe and affective environment while simultaneously maintain appropriate boundaries and authority. In addition, Lloyd and Hastings (2008) suggested that mindful parents are less likely to exhibit avoidant coping behavior in response to any child negativities related to developmental difficulties. In such instances, mindful parents tend to use less harsh discipline to their children.

As parents have a higher level of acceptance for their children and themselves, they are more likely to participate in common activities with their children. Mindfulness has been found to be positively associated with parental involvement in cases where children have developmental disabilities or learning difficulties (Singh et al. 2007, 2009). In addition, mindfulness helps parents to listen and speak to their children with their full attention. They are more sensitive to cues such as a child’s tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language. All these help parents recognize a child’s needs and be effectively involved with their children (Duncan et al. 2009). Furthermore, many previous studies supported that mindfulness is related to different forms of self-efficacy, such as the self-efficacy of coping, regulating emotion, and maternal parenting (Luberto et al. 2013; Byrne et al. 2014). A mother’s self-efficacy is also thought to be negatively associated with psychological and physical stress and is crucial to child development (Talge et al. 2007).

In a word, the present study examined the associations between mindfulness, parent–child interaction, and child behavior in a Chinese sample. Specifically, it examined the connections between the mother-child relationship, maternal mindfulness, and child social adjustments. The following hypotheses were tested: (i) the quality of maternal mindfulness was positively associated with mother-child relationships, (ii) both the maternal mindfulness and the quality of mother-child relationships positively predicted child social adjustments, and (iii) the mother-child relationship mediated the effect of maternal mindfulness on child social adjustments.

Method

Participants

Two-hundred and sixteen mothers participated in this study. The majority (72 %) were between 31 and 40 years old, 14 % were 30 or under, and a further 14 % were 41 or over. Most of the mothers worked full time (45 %), while 23 % worked part-time and 32 % were housewives. Approximately 72 % of the study population had completed secondary school, 13 % had completed post-secondary education, and 15 % had a university education. Most (98 %) of the recruited mothers were married; 35 % had one child, 57 % had two children, and 8 % had three children. Each mother had at least one child of preschool age, i.e., between 3 and 6 years old. In the families with two or more children, most of the children were either in nursery school or in the early grades of elementary school.

Procedure

Mothers were recruited from six kindergartens using a convenience sampling technique. The questionnaire was distributed to the mothers via the kindergartens. Mothers completed the questionnaire on a voluntary basis. The questionnaire took approximately 15 min to complete. All of the completed questionnaires were returned to the researcher via the kindergartens.

Measures

Parent–Child Relationship

Parent–child relationship was evaluated using the attachment and relational frustration subscales of the Parenting Relationship Questionnaire (PRQ; Kamphaus and Reynolds 2006). The PRQ, which uses a four-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, and 3 = almost always), is a measure designed to evaluate a parent’s perspective on the parent–child relationship. There are five subscales in the preschool version of the PRQ, attachment, discipline practice, involvement, parenting confidence, and relational frustration. The “attachment” subscale measures a parent’s awareness of his or her child’s emotions and thoughts and his or her ability to comfort to the child during times of distress. The “discipline practice” subscale measures the tendency of a parent to consistently apply consequences or punishment in response to a child’s misbehavior. The “involvement” subscale assesses the extent to which the parent and child participate together in a variety of common activities. The “parenting confidence” subscale measures the comfort and control of a parent when he or she is actively involved in parenting and when making parenting decisions. Finally, the “relational frustration” subscale measures the parental stress and frustration related to controlling child affect and behavior. For each subscale, the reliability was found to be relatively high, ranging from .82 to .87 (Rubinic and Schwickrath 2010).

The PRQ was translated into Chinese by a panel of three individuals fluent in both English and Chinese. The translated items were then translated back into English by another translator who had not been involved in the previous process. This version was compared to the original items in the PRQ to check for original meaning and intent, and the translated version was then finalized. Each step involved editing and revising the wording and sentence structure of the items (Geisinger 1994). The internal consistency of the items in the five subscales ranged from .71 to .86 in this sample.

Mindfulness

Trait mindfulness was evaluated using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown and Ryan 2003), which comprises 15 items, each of which is an affirmation expressed as a declarative sentence. This scale focuses on the presence or absence of attention on and awareness of what is occurring in the present moment. The respondents are asked to rate their level of agreement with each statement on a six-point scale (1 = almost always and 6 = almost never). Higher scores indicate greater mindfulness. The Chinese version of the MAAS has been shown to be a reliable and valid tool for assessing mindfulness in a Chinese population (e.g., Deng et al. 2012). The internal consistency of the items in this scale was .86 in this sample.

Child Social Behavior

Child social behavior was assessed using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 1997). The SDQ, a 25-item behavioral screening questionnaire with five subscales, is designed to assess psychological adjustment in children and adolescents across a broad area. The subscales assess four difficulties (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems) and one strength (prosocial behavior). Each behavioral item is rated on a three-point Likert scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, and 2 = certainly true). The SDQ has been widely used in different cultures, and the Chinese version has been verified in previous studies (e.g., Du et al. 2008; Lai et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2013). The internal consistency of the subscales ranged from .70 to .86 in this sample.

Data Analyses

The mean values and standard deviations for each subscale in parent–child relationship (attachment, discipline practice, involvement, parenting confidence, and relational frustration), mindfulness, and child social behavior (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior) were conducted, followed by the calculation of the inter-correlations. Relationships between all these studied variables were then evaluated by path analysis (a type of regression analysis) using a maximum likelihood estimator. The analysis was done with the use of the LISREL 8.51 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 2001).

Results

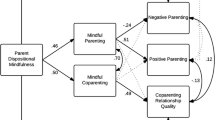

The mean values and standard deviations for each subscale in each of the three measures are shown in Table 1. The inter-correlations between the variables are listed in Table 2. Mindfulness was positively correlated with attachment, involvement, and parenting confidence. Conversely, mindfulness was negatively correlated with relational frustration, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems. The sizes of the correlations were consistent with the hypotheses. Subsequent path analyses used a regression approach to study the effect of each variable. The results of the path analyses are shown in Fig. 1.

The results of the path analysis demonstrated the antecedents and outcome relationships between the independent variable (IV) and the dependent variables (DVs). The only IV (mindfulness) exhibited a significant and positive effect on attachment (γ = .86, p < .001), discipline practice (γ = −.36, p < .001), involvement (γ = .68, p < .001), and parenting confidence (γ = .90, p < .001) and a significant and negative effect on relational frustration (γ = −.28, p < .001).

The path analysis also showed that attachment had a significant and negative effect on hyperactivity but no significant effect on emotional symptoms, conduct problems, peer problems, or prosocial behavior. Discipline practice had a significant and negative effect on peer problems but no significant effect on emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, or prosocial behavior. Involvement had a significant and positive effect on prosocial behavior and a significant and negative effect on emotional symptoms and peer problems. Conversely, involvement had no significant effect on conduct problem or hyperactivity. Parenting confidence had no significant effect on emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, or prosocial behavior. Relational frustration had a significant and positive effect on conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems but no significant effect on emotional symptoms or prosocial behavior. The direct effects of mediators on dependent variables are shown in Table 2.

Results of the path analysis suggested that mindfulness had a significant and negative indirect effect on emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems and a significant and positive indirect effect on prosocial behavior. As shown in Fig. 1, mindfulness had significant indirect effects on emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior via attachment, discipline practice, involvement, and relational frustration. The significant indirect effects of mindfulness (the only IV) on the explanatory DVs demonstrated that attachment, discipline practice, involvement, and relational frustration served as mediators between mindfulness and the other explanatory variables.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to test the pathways in a model which proposes associations between parental mindfulness, parent–child relationship, and child social behavior. As expected, the results indicated that maternal mindfulness had a direct positive effect on positive child social behavior and a negative effect on negative child social behavior. Mindfulness also made a significant and positive contribution to parent–child attachment, parental involvement, and parental parenting confidence and had a negative effect on parental frustration and discipline practice. In addition, the parent–children relationship served as the mediator between parental mindfulness and child social behavior.

First, our results suggested that attachment could mediate the effect of parental mindfulness on children’s social behavior. Previous research has found that securely attached adolescents are more resistant to ADHD symptoms. Consequently, securely attached adolescents exhibit more functional social adjustment (Scharf et al. 2014). Based on our results, our model could be extended to preschool children, as secure attachment is likely to have a significant and negative effect on child hyperactivity. During intimate relationships, individuals with higher mindfulness may have an open and receptive attitude toward the other and thus will respond more constructively to relationship difficulties (Ryan et al. 2007). Parents with high levels of mindfulness may serve as adaptive attachment figures for their children and nurture functional parent–child attachment patterns. The secure parent–child attachment can then be internalized by the child. Such securely attached children are likely to be less prone to hyperactivity and thus exhibit less hyperactive behavior. Moreover, findings of the current study replicate researches, showing that mindful parents are more involved with their children (Singh et al. 2007, 2009). Mindful parents have been shown to be aware of their children’s needs and are more able to provide timely support and care according to the children’s requirements. When communicating with children, mindful parents listen to and observe their children with their full attention (Duncan et al. 2009). They can effectively perceive their children’s feelings and needs and are more emotionally involved with their children; for example, they share their emotions with their children. Involvement is important to the social development of children. Our results showed that maternal mindfulness was positively related to involvement and that the involvement of mothers can in turn have a positive influence on children’s social behavior.

Our results also demonstrated that mindfulness was negatively related to children’s peer problems through the reduction of discipline practice. Previous studies have found an association between harsh discipline and child problem behavior and negative emotions (Chang et al. 2003). As mindfulness emphasizes non-judgment, acceptance, and compassion, mindful parents will set more effective limits on their children; compassion and love reduce parents’ harsh discipline and its negative influence on child behavior (Bögels and Restifo 2014; Duncan et al. 2009). Children of inductive mothers with less assertive discipline were more popular with their peers (Hart et al. 1992). Thus, parental mindfulness can indirectly influence children’s peer problems through discipline practice. Our results further suggested that maternal mindfulness had indirect effects on children’s conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems through a reduction in rational frustration. Mindfulness can improve an individual’s ability to self-regulate his or her emotions (Luberto et al. 2013). Mindful parents are less prone to ruminating on their children’s negativities and are more resistant to relational frustration (Kingston et al. 2007). Additionally, stressed parents who are frustrated with their parent–child relationships tend to overestimate the severity of their children’s maladaptive behavior (De Bruyne et al. 2009). Parents may perceive an association between their children’s negativities and their relational frustration (Snyder 1992; Snyder and Klein 2005). Mindfulness helps parents be more accustomed to a here-and-now attitude and help reduce their stress and parenting frustration. At last, our result showed that mindfulness of mother was positively related to parenting confidence, but our result did not support the mediating effect of parenting confidence. The possible explanation is that the dimension of parenting confidence refers more to parents’ self-evaluation and well-being but not directly contributes to children’s social behavior when compared with other dimensions of parent–child relationship.

In general, this study contributes to understanding how the parent–child relationship mediates the effect of maternal mindfulness on child social behavior. Although Duncan et al. (2009) have proposed the model linking mindful parenting and children’s behavior through the parent–child relationship, to our knowledge, the present study is the first empirical one to examine the relations between parental mindfulness, parent–child relationship, and child social behavior. Our results also provided empirical evidence to future practice as mindfulness intervention could be considered as one approach to improve parent–child relationship and child social behavior.

Several limitations should be taken into account when evaluating the study. First, the sample size was relatively small. Hence, generalization to other samples may be limited. Further, the data were collected on a self-report basis, so objective behavior may not be accurately reflected. The study used a cross-sectional survey design, so causal relationships between the variables could not be really established. Further longitudinal studies could identify the causal relationships.

Our results also have some implications for future studies. Future research can take fathers into consideration. The participants in most previous studies of parenting mindfulness have been primarily mothers (e.g., Geurtzen et al. 2015; Parent et al. 2011). However, mothers and fathers have many different roles in the parenting process and in parent–child relationships (Rothbaum and Weisz 1994; McBride and Mills 1993). Additionally, children’s gender may also affect these relationships (Fabes 1994). Future research should consider the effects of gender differences in the parenting process. Finally, our study only measured the awareness and attention aspects of mindfulness. If mindfulness is measured in a multi-faceted construct, different findings may emerge. In all, mindfulness of parents is a construct deserving further attention from various perspectives.

References

Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44, 709–716.

Altmaier, E., & Maloney, R. (2007). An initial evaluation of a mindful parenting program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 1231–1238.

Baer, R. A., & Krietemeyer, J. (2006). Overview of mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatment approaches. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications (pp. 3–27). London: Elsevier.

Bishop, S., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Bögels, S., & Restifo, K. (2014). Mindful parenting: a guide for mental health practitioners. New York: Springer.

Bögels, S. M., Lehtonen, A., & Restifo, K. (2010). Mindful parenting in mental health care. Mindfulness, 1, 107–120.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52, 664–678.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Byrne, J., Hauck, Y., Fisher, C., Bayes, S., & Schutze, R. (2014). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based childbirth education pilot study on maternal self-efficacy and fear of childbirth. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 59, 192–197.

Chang, L., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598–606.

Dawe, S., & Harnett, P. (2007). Reducing potential for child abuse among methadone-maintained parents: results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32, 381–390.

De Bruyne, E., Van Hoecke, E., Van Gompel, K., Verbeken, S., Baeyens, D., Hoebeke, P., & Walle, J. V. (2009). Problem behavior, parental stress and enuresis. The Journal of Urology, 182, 2015–2021.

Deng, Y. Q., Li, S., Tang, Y. Y., Zhu, L. H., Ryan, R., & Brown, K. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Chinese translation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Mindfulness, 3, 10–14.

Du, Y., Kou, J., & Coghill, D. (2008). The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in China. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2, 1–15.

Dumas, J. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 779–791.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 255–270.

Fabes, R. A. (1994). Physiological, emotional, and behavioral correlates of gender segregation. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1994, 19–34.

Geisinger, K. F. (1994). Cross-cultural normative assessment: translation and adaptation issues influencing the normative interpretation of assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment, 6, 304–312.

Geurtzen, N., Scholte, R. H., Engels, R. C., Tak, Y. R., & van Zundert, R. M. (2015). Association between mindful parenting and adolescents’ internalizing problems: non-judgmental acceptance of parenting as core element. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1117–1128.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Hart, C. H., DeWolf, D. M., Wozniak, P., & Burts, D. C. (1992). Maternal and paternal disciplinary styles: relations with preschoolers’ playground behavioral orientations and peer status. Child Development, 63, 879–892.

Hertz, R. M., Laurent, H. K., & Laurent, S. M. (2014). Attachment mediates effects of trait mindfulness on stress responses to conflict. Mindfulness, 6, 483–489.

Jöreskog, K., & Sörbom, D. (2001). LISREL 8.51: user’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Kabat-Zinn J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156.

Kabat-Zinn, M., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (1997). Everyday blessings: the inner work of mindful parenting. New York: Hyperion.

Kamphaus, R. W., & Reynolds, C. R. (2006). Parenting Relationship Questionnaire. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson SAGE Publications, Inc.

Kingston, T., Dooley, B., Bates, A., Lawlor, E., & Malone, K. (2007). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 80, 193–203.

Lai, K., Luk, E., Leung, P., Wong, A., Law, L., & Ho, K. (2010). Validation of the Chinese version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in Hong Kong. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 1179–1186.

Larzelere, R. E. (2000). Child outcomes of non-abusive and customary physical punishment by parents: an updated literature review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology, 3, 199–221.

Liu, S. K., Chien, Y. L., Shang, C. Y., Lin, C. H., Liu, Y. C., & Gau, S. S. F. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54, 720–730.

Lloyd, T., & Hastings, R. P. (2008). Psychological variables as correlates of adjustment in mothers of children with intellectual disabilities: cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52, 37–48.

Luberto, C. M., Cotton, S., McLeish, A. C., Mingione, C. J., & O’Bryan, E. M. (2013). Mindfulness skills and emotion regulation: the mediating role of coping self-efficacy. Mindfulness, 5, 373–380.

McBride, B. A., & Mills, G. (1993). A comparison of mother and father involvement with their preschool age children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8, 457–477.

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–101.

Parent, J., Garai, E., Forehand, R., Roland, E., Potts, J., & Haker, K. (2011). Parent mindfulness and child outcome: the roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness, 1, 254–264.

Rothbaum, F., & Weisz, J. R. (1994). Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 55–74.

Rubinic, D., & Schwickrath, H. (2010). Test review: parenting relationship questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28, 270–275.

Rudd, J. E., Vogl-Bauer, S., Dobos, J. A., Beatty, M. J., & Valencic, K. M. (1998). Interactive effects of parents’ trait verbal aggressiveness and situational frustration on parents’ self-reported anger. Communication Quarterly, 46, 1–11.

Ryan, R. M., Brown, K. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). How integrative is attachment theory? Unpacking the meaning and significance of felt security. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 177–182.

Scharf, M., Eshkol, V., Oshri, A., & Pilowsky, T. (2014). Adolescents’ ADHD symptoms and adjustment: the role of attachment and rejection sensitivity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 209–217.

Shapiro, S. L., & White, C. (2014). Mindful discipline: a loving approach to setting limits and raising an emotionally intelligent child. CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., Curtis, W. J., & Wahler, R. G. (2007). Mindful parenting decreases aggression and increases social behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification, 31, 749–771.

Singh, N. N., Singh, A. N., Lancioni, G. E., Singh, J., Winton, A. S. W., & Adkins, A. D. (2009). Mindfulness training for parents and their children with ADHD increases the children’s compliance. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 157–166.

Snyder, M. (1992). Motivational foundations of behavioral confirmation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 67–114). San Iliego, CA: Academic Press.

Snyder, M., & Klein, O. (2005). Construing and constructing others: on the reality and the generality of the behavioral confirmation scenario. Interaction Studies, 6, 53–67.

Talge, N. M., Neal, C., & Glover, V. (2007). Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 245–261.

van der Oord, S., Bogels, S. M., & Peijnenburg, D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child Family Study, 21, 139–147.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siu, A.F.Y., Ma, Y. & Chui, F.W.Y. Maternal Mindfulness and Child Social Behavior: the Mediating Role of the Mother-Child Relationship. Mindfulness 7, 577–583 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0491-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0491-2