Abstract

The body plethysmography (BPG) is a useful tool for analyzing pulmonary function in small animals because it simultaneously measures airway resistance (R aw) and functional residual capacity (FRC). We previously described a BPG with the enclosed environment maintained at body temperature and water vapor-saturated. We found dose-dependent increases in R aw in response to inhaled methacholine (Mch) with no apparent increase in FRC in intratracheally intubated rats without paralysis. To resolve this apparent inconsistency in clinical observations, we repeated the study using a newly developed BPG that allowed us to shorten the interval between Mch-inhalation and measurements by about two-thirds. Using Mch concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 mg/ml each for 2 min, both parameters increased in a dose-dependent fashion with FRC (mean ± SE) values of 3.77 ± 0.16, 4.43 ± 0.26, 4.75 ± 0.34, 5.02 ± 0.49 and 5.34 ± 0.38 ml and R aw values of 18.6 ± 3.9, 21.6 ± 4.9, 35.0 ± 6.9, 49.0 ± 8.8 and 65.7 ± 8.8 ml/s/Pa, respectively. Immediate measurement after Mch-inhalation demonstrated profound bronchoconstriction associated with dose-dependent increases in FRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, animal studies on obstructive pulmonary diseases have been largely concerned with morphologic or molecular changes in the lung and airways. However, the role of pulmonary function in these diseases is now being reappraised. For example, pulmonary overinflation is thought to be an important causative factor of dyspnea. It also plays a crucial role in the restriction of diaphragmatic motion in COPD and bronchial asthma [1–5]. However, pulmonary function, particularly lung volume, in the animal model of obstructive pulmonary diseases remains to be further elucidated.

We recently reported the applicability of the body plethysmograph (BPG) for estimation of obstructive changes in small animals [6], permitting the simultaneous measurement of airway resistance (R aw) and lung volume [6, 7]. Transiently maintaining gases in the BPG at BTPS (body temperature, atmospheric pressure and water vapor saturated), we measured R aw in rats without requiring any special maneuver or assumptions [6]. In that study, we observed dose-related increases in R aw during methacholine (Mch) inhalation with no significant change in FRC [6], contrary to clinical studies, in which lung volume is reported to be increased during acute bronchoconstriction [1, 8]. Since, with our apparatus, it took 8 to 10 minutes before reaching a BTPS steady state, the bronchoconstrictive effect of Mch might have partially dissipated in this interval. We reasoned that more profound bronchoconstriction measured earlier might have been associated with a significant increase in FRC. To test this hypothesis, in this study, we developed a new BPG that shortened the interval between Mch exposure and the measurements.

Animals and methods

The basic design of the BPG was the same as that reported previously (Fig. 1) [6]. The enclosed environment of the BPG was transiently kept at BTPS. The capacity of the BPG was 1,170 ml, and the volume of water circulating around the BPG was 800 ml. Both were much smaller than those of the previous system, i.e., 1,950 ml and 1,800 ml, respectively. Power of the electronic elements controlling the temperature of the circulating water was also increased from 240 to 800 W. Temperature and humidity in the BPG were continuously measured to determine whether the environment in the BPG reached BTPS condition. FRC was measured by the standard method [9]. R aw was measured in the absence of panting respiration.

Basic mechanism of the present BPG. BPG was made of two layers. Water around the rectal temperature was circulated in the space between the two layers. An ultrasonic humidifier kept humidity in the BPG >80%. Temperature (°C) and humidity (%) and pressure (P box) in the BPG were continuously measured. Rat’s rectal temperature was also continuously measured

Subjects were nine 8-week-old male Wistar rats (body weight 230–260 g). They were anesthetized with i.p. pentobarbital (0.05 mg/g) and were tracheally cannulated with a 14-gauge plastic needle. The rats were placed in supine position in the BPG, and their rectal temperature and respiratory flow (a screen-type pneumotachometer, TV-241T, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) were continuously monitored. When the BPG environment reached BTPS, the airway shutter was closed at FRC. Respiratory flow (flow), tracheal pressure (P aw) and intra-box pressure (P box; TP-602T, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) were continuously measured and stored in a PowerLab system (AD Instrument, Australia) with 2-kHz sampling rate. FRC was calculated from P aw and P box at airway closure, and the mean of three trials was regarded as a representative value. R aw was calculated from flow and P box.

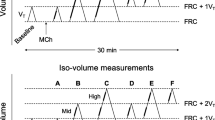

FRC and R aw were measured immediately after exposure to saline or Mch mists (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 mg/ml) for 2 min. Saline or Mch exposures were performed by placing the rats in a sealed box, and mist was generated within it by an ultrasonic humidifier (Soniclizer, Atom, Japan). Immediately after the inhalation (<5 s), the rat was moved to the BPG. Within 2.5 min after placing the rats exposed to saline or Mch in BPG, the environment in the BPG reached BTPS.

To confirm that the bronchoconstrictive effect produced by inhaled Mch is short, an additional experiment was done in another three anesthetized and tracheostomized rats. As shown in the inset picture in Fig. 4, the rats were placed in an air-tight box of 650 ml capacity. The tracheal cannula penetrated through the wall of the box and was connected to a flowmeter (TV-241T, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). Negative pressure of 15 cmH2O for 0.02 s was intermittently applied to the gas in the box, and thus this system worked as a body-surface ventilator. Immediately after Mch inhalation (8.0 mg/ml for 2 min), rat’s respiratory flow driven by mechanical ventilation was continuously measured.

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Tokai University.

Statistical analyses were done with a paired t-test using a Stat-View software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). When the p-value was less than 0.5, the difference was considered to be significant.

Results

Figure 2 shows FRC at each concentration of inhaled Mch. Exact values of FRC (mean ± SE) were as follows: 3.77 ± 0.16 ml (saline), 4.43 ± 0.26 ml (0.5 mg/ml), 4.75 ± 0.34 ml (1.0 mg/ml), 5.02 ± 0.49 ml (2.0 mg/ml) and 5.34 ± 0.38 ml (4.0 mg/ml). FRC was increased in proportion to Mch concentration. In comparison with FRC following saline inhalation, those at 1.0 mg/ml and 4.0 mg/ml were significantly larger. Although those at 0.5 mg/ml and 2.0 mg/ml were not significantly different, their p-values were 0.0739 and 0.0579, respectively.

Figure 3 shows R aw at each concentration of inhaled Mch. Exact values of R aw were as follows: 18.6 ± 3.94 ml/s/Pa (saline), 21.6 ± 4.9 ml/s/Pa (0.5 mg/ml), 35.0 ± 6.9 ml/s/Pa (1.0 mg/ml), 49.0 ± 8.8 ml/s/Pa (2.0 mg/ml) and 65.7 ± 8.8 ml/s/Pa (4.0 mg/ml). R aw increased with Mch concentration. In comparison with R aw following saline inhalation, all except that at 0.5 mg/ml were significantly increased.

Figure 4 shows an example showing changes in respiratory flow after Mch inhalation. In all three rats, there was no apparent suppression of the respiratory flow by inhaled Mch at less than 2.0 mg/ml concentration. As shown in Fig. 4, in response to 8.0 mg/ml Mch inhalation, respiratory flow slowly recovered from the suppression, but it reached a plateau level at 6, 16 and 16 min after inhalation, respectively.

Discussion

Precision of the system

Our previous BPG [6, 7] was a sealed box with a capacity of 1,950 ml. Approximately 1,800 ml of water circulated around the box, and the water was warmed or cooled by electronic elements with 240 W power. Since the BPG measures the respiratory fluctuations of P box, the large capacity of the BPG may have lowered the sensitivity of the P box changes. In contrast to the previous apparatus, the capacity of the newly designed BPG was only 1,170 ml. Since gas volume in the BPG is calculated as “box capacity − rat body weight (almost equal to volume),” if the rat body volume was assumed to be 250 ml, gas volume in the new BPG was decreased from 1,700 ml (i.e., 1,950 ml − 250 ml) to 920 ml (i.e., 1,170 ml − 250 ml). This reduction of BPG gas volume doubled the accuracy of measurement compared with the previous apparatus and also contributed to shortening the time for humidification.

In the new BPG, circulating water volume was decreased by 44%, while thermo-elements power was increased by 330%. As a result, thermo-control capability of the new system increased by eight fold compared with the previous BPG. CO2 production during quiet breathing in a rat is reported to be 1.0 ml/100 g/min [10]. If it takes 8 min to reach BTPS, CO2 concentration then would be ~2.0%. Hyperventilation caused by this hypercapnia should have changed the FRC level [11].

FRC and R aw

Using the new BPG system, we obtained a more profound bronchoconstrictive response and dose-dependent increases in FRC after Mch inhalation. Although the increases in FRC at 0.5 mg/ml and 2.0 mg/ml did not reach statistical significance, the p-values for them were small, suggesting that statistical significance could have been obtained if more animals had been examined. Shortening the interval between Mch inhalation and measurement, as well as improved accuracy of the system, may have contributed to these results. Owing to the reduction of box capacity and to improvement of thermo-control function, the time between Mch inhalation and R aw measurement was shortened by approximately two-thirds or more compared with the previous study. The duration of the bronchoconstrictive effect produced by aerosolized Mch in human subjects is reported to be ~20 min and that produced in rats by intravenous Mch is also <20 min [12], and ~10 min in sheep [13]. We confirmed that duration of the bronchoconstrictive effect produced by inhaled Mch in the rat is less than 15 min (Fig. 4). Therefore, profound bronchoconstriction can be demonstrated if BPG analysis is done immediately after Mch inhalation.

We found dose-dependent increases in FRC after Mch inhalation using the new BPG. FRC in response to the maximum concentration (4.0 mg/ml) increased by 1.6 ml, equivalent to 41% over that prior to Mch inhalation. This increase coincided with clinical observations [1, 8]. Increases of lung volume during Mch inhalation in paralyzed rats was also reported by Stengel et al. [14]. They measured excised lung volume after rats were killed. Thus, the condition of their rats was quite different from ours, but their report reinforces our result. The mechanism of the FRC increase during bronchoconstriction has not been fully established. One possible mechanism is continuous activation of inspiratory muscles [15]; another is air trapping, i.e., a check valve mechanism [16]. The disadvantages of pulmonary hyperinflation on respiratory mechanics have been previously described as reflected by significant improvement in pulmonary function after volume reduction surgery in patients with COPD [17]. Recent studies have shown that pulmonary hyperinflation plays important roles in restriction of diaphragmatic motion and in development of dyspnea in obstructive lung diseases [3, 4].

The maximum R aw associated with the highest Mch concentration (4.0 mg/ml) represented a three-fold increase over that prior to Mch inhalation, and this value was approximately double that in the previous study. The response to Mch in our study was more profound than that measured with the forced oscillation method, which is widely used for measuring R aw in small animals [18]. Using forced oscillation, the increase in R aw after 4 mg/ml Mch inhalation was reported to be ~150% of that prior to Mch inhalation [19]. However, in the forced oscillation study rats were open chest, paralyzed and artificially ventilated [19, 20]. This condition is associated with periodic pulmonary hyperinflation that suppresses the airway response to bronchoconstrictive agents [20]. Therefore, another advantage of the BPG in addition to concurrent measurement of FRC and R aw is that the study can be performed in more physiological conditions with spontaneous breathing and without muscular paralysis.

In conclusion, when the bronchoconstrictive response to inhaled Mch is profound, dose-dependent increases in FRC can be observed.

References

Lougheed MD, Fisher T, O’Donnell DE (2006) Dynamic hyperinflation during bronchoconstriction in asthma. Chest 130:1072–1081. doi:10.1378/chest.130.4.1072

Sorkness RL, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Chung KF, Curran-Everett D, Erzurum SC, Gaston BM, Israel E, Jarjiour NN, Moore WC, Peters SP, Teague WG, Wenzel SE (2008) Lung function in adults with stable but severe asthma: air trapping and incomplete reversal of obstruction with bronchodilation. J Appl Physiol 104:394–403. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00329.2007

Peters MM, Webb KA, O’Donnell (2006) Combined physiological effects of bronchodilators and hyperoxia on exertional dyspnea in normoxic COPD. Thorax 61:559–567. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.053470

Ofir D, Lavenziana P, Webb KA, Lam Y-M, O’Donnel DE (2008) Mechanism of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177:622–629. doi:10.1164/rccm.200707-1064OC

Ottenheijm CAC, Heunks LMA, Dekhuijzen PNR (2007) Diaphragmatic muscle fiber dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:1233–1240. doi:10.1164/rccm.200701-020PP

Tajiri S, Kondo T, Yamabayashi H (2006) Functional residual capacity and airway resistance of the rat measured with a heat- and temperature-adjusted body plethysmograph. J Physiol Sci 56:449–454. doi:10.2170/physiolsci.RP004506

Tazaki G, Kondo T, Tajiri S, Tsuji C, Shioya S, Tanigaki T (2006) Functional residual capacity and airway resistance in rats of COPD model induced by systemic hyaluronidase. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 31:115–117

Gibson GJ (1996) Pulmonary hyperinflation a clinical overview. Eur Respir J 9:2640–2649. doi:10.1183/09031936.96.09122640

West JB (1998) Pulmonary pathophysiology—the essentials, 5th edn. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Cragg PA (1983) Interaction of hypoxia and hypercapnia on ventilation, tidal volume and respiratory frequency in the anesthetized rat. J Physiol 341:477–493

Cha EJ, Sedlock D, Yamashiro SM (1987) Changes in lung volume and breathing pattern during exercise and CO2 inhalation in humans. J Appl Physiol 62:1544–1550. doi:10.1063/1.339626

Alonen RO, Mattila MJ (1981) Dose-related bronchoconstriction with methacholine in rats as modified terbutaline alone and combination with theophylline. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol 48:193–198

Wagner EM, Jacoby DB (1999) Methacholine causes reflex bronchoconstriction. J Appl Physiol 86:294–297

Stengel PS, Yiamouyiannis CA, Obenchain RL, Cockerham SL, Silbauch SA (1995) Methacholine-induced pulmonary gas trapping in guinea pigs, hamsters, mice and rats. J Appl Physiol 79:2148–2153

Martin JG, Powell E, Shore S (1980) The role of respiratory muscles in the hyperinflation of bronchial asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 121:441–447

Pellegrino R, Violante B, Nava S, Rampulla C, Brusasco V, Rodarte JR (1993) Expiratory flow limitation and hyperinflation during methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction. J Appl Physiol 75:1720–1727

Marchand E, Gayan-Ranirez G, De Leyn P, Decramer M (1999) Physiological basis of improvement after lung volume reduction surgery for severe emphysema: what are we? Eur Respir J 13:686–696. doi:10.1183/09031936.99.13368699

Bates JHT, Irvin CG (2003) Measuring lung function in mice: the phenotyping uncertainty principle. J Appl Physiol 94:1297–1306

Petak F, Hantos Z, Adamicza A, Asztalos T, Sly PD (1997) Methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in rats: effects of intravenous vs. aerosol delivery. J Appl Physiol 82:1479–1487. doi:10.1063/1.365927

Hirai T, Bates JHT (2001) Effects of deep inspiration on bronchoconstriction in the rat. Respir Physiol 127:201–215. doi:10.1016/S0034-5687(01)00243-2

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education and Sciences in Japan. We appreciate Miss Y. Takahari and Miss K. Iwao (Support Center of Medical Studies, Tokai University) for their excellent technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Kondo, T., Tanigaki, T., Tsuji, C. et al. Aerosolized methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction and pulmonary hyperinflation in rats. J Physiol Sci 59, 341–345 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-009-0040-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-009-0040-z