Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the psychological well-being and social barriers among immigrant Chinese American breast cancer survivors. The aim of the present study was to explore the social needs and challenges of Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors.

Method

This study used the expressive writing approach to explore the experiences among 27 Chinese American breast cancer survivors. The participants were recruited through community-based organizations in Southern California, most of whom were diagnosed at stages I and II (33 and 48%, respectively). Participants, on average, had been living in the USA for 19 years. Participants were asked to write three 20-min essays related to their experience with breast cancer (in 3 weeks). Participants’ writings were coded with line-by-line analysis, and categories and themes were generated.

Results

Emotion suppression, self-stigma, and perceived stigma about being a breast cancer survivor were reflected in the writings. Interpersonally, participants indicated their reluctance to disclose cancer diagnosis to family and friends and concerns about fulfilling multiple roles. Some of them also mentioned barriers of communicating with their husbands. Related to life in the USA, participants felt unfamiliar with the healthcare system and encountered language barriers.

Conclusion

Counseling services addressing concerns about stigma and communication among family members may benefit patients’ adjustments. Tailor-made information in Chinese about diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer and health insurance in the USA may also help patients go through the course of recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in American women of all ethnic and racial groups, and its detection and treatment have improved in the last few decades [1]. Asian Americans are the most diverse and fastest growing ethnic group in the USA, yet the incidence rates of breast cancer in this population are increasing [2]. In addition, Asian American breast cancer survivors commonly reported fear, anger, and depression, which are directly associated with their quality of life [3, 4]. Compared to other ethnic groups, they showed the lowest scores in some of the indicators of emotional well-being after active treatments [5]. The reasons behind such low levels of emotional well-being remain unclear because only a few studies have examined the breast cancer survivorship experience of Asian Americans, compared to non-Hispanic white and African Americans [6].

Twenty-three percent of Asian Americans are Chinese, making Chinese Americans the largest subgroup [7]. Researchers however have not investigated the cancer experiences of Chinese Americans in much detail. Chinese American breast cancer survivors may share some of the same challenges as other Asian Americans survivors, e.g., lack of knowledge or language barriers [8]. Conversely, traditional Chinese cultural values, such as Confucian and collectivistic values, could give rise to some particular social barriers that influence their health and quality of life. Currently, there is a paucity of studies examining the breast cancer survivorship experience of Chinese American immigrants. Therefore, the present study aimed to address this gap by studying the social needs and challenges using an expressive writing approach.

Role of Culture

Many Chinese Americans are first-generation immigrants; traditional cultural beliefs play a significant role in how they perceive and respond to health changes. For instance, they value traditional Chinese medication [9], and their family members take major roles in the treatment decision-making process [10]. Chinese cultural beliefs regard “physicians as authority figures,” and it may lead to a lack of adequate communication and questioning with physicians [4, 11].

The concept of acculturation is important in the study of immigrants, and it quantifies the process of “cultural change and adaptation that occur when individuals from different cultures come into contact” [12]. Among Chinese American breast cancer survivors, the level of acculturation was shown to be positively associated with levels of social support and negatively associated with the level of life stress [13]. Some survivors believed that cancer meant death, and they had done something to deserve getting cancer [14]. Therefore, they found it difficult to disclose their illness to their parents and friends [14].

These studies demonstrate the potential role of Chinese culture on social challenges, such as insufficient social support and patient-physician communication. It is essential to further identify and address these social challenges of Chinese American breast cancer survivors because they may impact the quality of life among these populations [5].

Social Support and Challenges Can Affect Breast Cancer Survivors’ Well-Being

It is well known that social factors, such as social support, can influence breast cancer survivors’ health and coping experience. Several studies have reported the social barriers faced by Asian American breast cancer survivors, yet the particular social needs and challenges faced by Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors are relatively unknown [4, 6]. Among Asian American breast cancer survivors, social support was central to their quality of life, and the primary source of social support was their nuclear family members [8, 14]. Family social support was instrumental for adjustment among Chinese cancer survivors [15]. They perceived social support as helpful in buffering psychological distress and providing valuable information [8, 10]; however, they tend to have smaller social networks and less support than European Americans [16]. Similarly, many Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors reported that they had less social support than they would have if they were in their home country [10]. Furthermore, Asian American breast cancer survivors do not utilize social support resources. They expressed greater difficulties in seeking emotional help from their families because they did not want to become burdens on their families [5]. They also had lower levels of utilization of social support outside of family and professional assistance than European Americans [16, 17]. Some Chinese American cancer survivors even expressed that they felt embarrassed to ask for help [10].

Asian American breast cancer survivors endure and confront many social barriers. Regarding Chinese American breast cancer survivors, they may or may not share the same barriers, and therefore, it is necessary to further investigate the social needs and challenges in this population specifically. By becoming aware of these needs and challenges, future researchers and policymakers can put into place certain strategies and interventions.

The Present Study

The primary goal of this paper was to identify the social needs and challenges expressed by Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors. This paper also identified the potential psychological and behavioral consequences associated with these challenges. By exploring these needs and challenges as well as the associated consequences, our findings would shed some light on the key issues that need to be considered when designing interventions and policies for this group of breast cancer survivors.

The majority of qualitative data regarding Asian American breast cancer survivorship experience comes from in-depth interviews [4, 10, 18], and very few of them specifically target Chinese American breast cancer survivors [6]. Chinese American breast cancer survivors may hesitate to share their feelings and thoughts via interviews because of culturally specific obstacles, such as cancer-related stigmas and a norm of suppressing emotions [14, 19]. Yet, expressive writing is a private and guided writing exercise that provides a way for these participants to overcome those obstacles and disclose their emotions and thoughts. This approach has been previously used to reveal Chinese American breast cancer survivors’ beliefs about breast cancer and its treatments [20]. Therefore, this study was extended to explore the social needs and challenges of Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors using the same expressive writing paradigm.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection

Twenty-seven Chinese breast cancer survivors living in Southern California were recruited for the expressive writing study. Participants were recruited through community-based cancer organizations in Southern California. Inclusion criteria of participants were (1) self-identified to be comfortable writing and speaking in Chinese (i.e., Mandarin and Cantonese), (2) being less than 5 years since their cancer diagnosis, and (3) having breast cancer diagnosis of stages I–III. The majority of them were born in mainland China or Taiwan (89%) and were married (70%). All the participants had been living in the USA for at least 5 years (on average 19 years). They had (some) college education (74%) and did not have full-time employment (67%). About half (41%) had an annual income of less than $15,000. Most of them were diagnosed at either stage I (33%) or stage II (48%) breast cancer. Table 1 details the participants’ characteristics.

In the expressive writing study [21, 22], participants were asked to write continuously for 20–30 min each week in Chinese at home over the course of 3 weeks. They wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings regarding cancer diagnosis and treatment (week 1), the most stressful experience regarding cancer and treatment (week 2), and positive experiences regarding breast cancer (week 3). This writing task aimed to facilitate emotional disclosure, effective coping, and benefit-finding, which would work together to bring stressors and personal goals into awareness and regulate thoughts and emotions relevant to the cancer experience [21, 22]. Participants were compensated $15 for completing the three writing essays and $70 gift certificate for completing the study (including the essays). Women wrote a minimum of one page and a maximum of three pages. The essays produced from this previous study [21, 22] were analyzed in the present study.

Data Analysis

The essays were analyzed in three phases. First, a phenomenological research method [23] was employed. All essays were read to understand the overall experience. Meaningful units were identified and translated into psychological language and synthesized to create themes and subthemes. Second, line-by-line content analyses were conducted to categorize relevant sentences into themes and subthemes. Two bilingual researchers independently coded each essay. Third, cultural meanings were extracted to link different subthemes and form a comprehensive story explaining phenomena identified during the first phase. Any disagreement was discussed among the authors until a consensus was reached. As re-readings and discussions progressed, new subthemes and themes emerged and some of the pre-identified ones were deleted. Subthemes were regrouped into major themes until no new themes emerged. The three phases were repeated and reiterated, until all investigators agreed that a comprehensive story was formed to describe and explain the needs among participants.

Results

The social needs and challenges identified in the participants’ writings about their experiences were in two domains. Culturally unique issues and the difficulties they faced as immigrants were described in their essays. Participants believed that both were major sources of stress in their lives. They also thought that the negative psychological responses of these social issues and barriers were associated with several consequences. These themes were interrelated and detailed with translated quotes from participants’ essays below.

There was no discernable pattern or differences found between cancer stages or time since diagnosis. These themes were described by women who had stage I, II, and III as well as women who had been diagnosed less than a month to 5 years ago. The identified themes were shared experiences across Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors. The major themes were present during diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.

Culturally Unique Issues

Cancer-Related Stigma

Participants experienced stigma associated with cancer (including self-stigma and perceived stigma). They labeled themselves as “tainted,” “less desirable,” or “handicapped” [self-stigma; 24] and felt that they were being avoided or rejected by others [25] because of their disease. In Chinese society, there is a personal responsibility attached to cancer along with widespread cancer-related social stigma [14]. Often, cancer is thought to be due to some immoral behavior conducted by the individual or an ancestor and, therefore, is the result of karma or bad luck.

Participants were sensitive to any avoidance behaviors by other people and attributed them to their cancer. One participant believed that her friends would think that cancer was contagious and would treat her differently.

ID07: Some people knew that I got cancer; they and my friends seemed to stay away from me intentionally. They were afraid of catching the disease from me…I remembered my hair started falling off ten days after the chemo … They just said hello and went away when they see me.

Another felt that people were avoiding her like “a pandemic.”

ID017: When I ran into friends I haven’t seen for a while, and told them about my illness, they asked me how I discovered it right away.... And truly, some people try to avoid me like hiding from a plague.

A participant described that she felt ashamed about having breast cancer when she could no longer conceal it after losing her hair. She was embarrassed by the changes in her body after the treatments.

ID07: “I felt ashamed to see others after I became bald, even with my cap on.”

Goal for Harmony

Cancer diagnosis and treatment elicited a variety of strong negative emotions [26, 27], many of which the participants articulated in their writings. Chinese culture values emotion suppression as a way not to disturb the harmonious equilibrium of interpersonal transactions [28]. That is, if the expression of emotion will harm group harmony, their true feelings are not revealed. In order not to disturb or burden their family and friends, survivors chose to keep emotions to themselves and hide their feelings.

ID19: I didn’t want my husband to know how frightened I was. I forced myself not to cry in front of people and tried to suppress my emotion. I didn’t want my son to know (about the cancer) either, so I chose to stay at the office every night to avoid seeing my husband and son.

Although Chinese people regard family as the primary source of support [14], some of the participants wrote about their reluctance to disclose their cancer diagnosis to their family and/or friends. Some women did not disclose their condition because they did not want to burden their family.

ID19: I was afraid to tell my aged mom and my two sisters who were already leading a hectic life making a living. I was afraid that my aged mom could not bear the horrible news. And I didn’t want my two busy sisters to worry about me, so I didn’t dare to tell them all along.

ID07: I didn’t even tell my husband and daughter. I was afraid they would be distressed. So I was the only one who knew this (breast cancer diagnosis).

ID02: When I knew the tumor was malignant, I was in the USA and I didn’t know if I should tell my parents, my husband and kids in my home country. I didn’t tell my relatives in my home country until the entire course of treatment was over, so that they would not feel too worried. It was a big challenge when I decided to bear it alone.

Such a concern may reflect the prominence of family harmony in traditional Chinese values, which is a very common value among Chinese women [29, 30].

Barriers to Expressing Emotions

Chinese people may not be comfortable to openly disclose emotions; thus, these breast cancer survivors tended to actively suppress emotions (especially negative emotions) [10]. They wrote about barriers to effectively communicate with their husbands about their emotional needs, changes in family roles, and preference of treatments. Among those who did inform their husbands about their breast cancer diagnosis, many acknowledged receiving support from their husbands during treatment and recovery. However, this support was not always considered to be sufficient. Moreover, they had difficulty expressing the need for this support due to role changes and challenges faced as a breast cancer survivor which often led to insufficient support from others.

ID03: I had a feeling that my husband didn’t look after me attentively. When men are sick, we always take good care of them. Things become so different when we get sick. They even found minor things to quarrel sometimes.

ID21: Sometimes I felt like I can’t share my inner thoughts with my husband; sometimes I didn’t want to because I think it was useless even if I shared these thoughts with him… What I needed was only a few comforting words like “it won’t be a problem” or just a hug, but I could not even get that.

ID19: Even when I was confused and distressed, (my husband) insisted his way selfishly. My husband put me in even greater pressure and distress, and I could hardly breathe. During the whole treatment, whether it was during chemo or radiation, I could never do things according to my own will. Whenever I needed to make a choice, my husband always forced me to do things according to his will; things are the same even now.

The participants who disclosed their diagnosis discussed the inadequacy of their husbands’ support which resulted in greater distress and less willingness to open up and seek further support from them. Thus, husbands, although the primary source, may not always be the appropriate source of support during breast cancer treatment and recovery.

Women’s Role as the Major Caregiver

Being brought up in a patriarchal society, Chinese women are expected to be the nurturers and caregivers in the family structure [4]. This cultural role becomes an essential part of their identity and a priority in their lives [29, 30]. Therefore, the feeling of burdening the family and incapability of fulfilling family responsibilities were sources of distress among the women. Participants wrote about being more concerned about their family than about themselves when thinking about the consequences of their disease. For, example, concerns about dying and their families having to live without them were revealed

ID05: Whatever amount of emotional stress I experienced was mostly due to concerns over my husband and children. Occasionally the thought of them living life without me would grieve my heart.

ID18: I felt painful in my heart because I did not want to put my mom in distress…

ID20: I was worried about my two young daughters because I couldn’t imagine how they would live in the days without their mom. Furthermore, I was afraid that my husband couldn’t take care of them.

Three participants specifically expressed their difficulties in fulfilling their responsibilities as daughters, mothers, and wives during treatment and recovery with their weakened body.

ID01: The surgery and chemo afterwards made my body suffer a lot, but as a mom, daughter, and wife, I had a lot to do and care about. Sometimes I felt the spirit was willing but the flesh was weak.

ID17: I myself was a patient, and I had to take care of my 90-year-old mom. I felt myself languish a lot.

Challenges Experienced as Immigrants

Participants expressed experiencing multiple sources of stress related to their different identities from being (a) an immigrant and (b) a breast cancer survivor. All the participants had been living in the USA for several years; however, problems arose when they not only had to live in a non-native country but also had to live with cancer. The difficulties experienced related to language barriers, access to care, finances, and the availability of social support.

Language Barriers

One of the major struggles for Chinese immigrants is the language. Our participants revealed that communications with health professionals, service providers, and insurance companies were challenging due to issues surrounding speaking and understanding in a non-native language. One participant (ID02) mentioned: “The biggest problem I faced was language. My English was not good, and I felt helpless and in pain.” This inability to communicate effectively due to language barriers became one of the greatest challenges to fully understanding the comprehensive and vital information about breast cancer treatments. Thus, as understanding was hindered, there was a heavy reliance on the physicians and decisions concerning treatment were very much physician led.

Lack of Insurance and Unfamiliarity with Healthcare System

Other challenges described by participants were a lack of health insurance and an unfamiliarity with the healthcare system in the USA. One participant in particular was entirely unaware that she was eligible for health insurance.

ID07: It was then I decided to tell my friends that I can live no longer than a year. My friend told me that I shouldn’t be afraid of medical cost in the USA even though I was poor and said, “let me help you apply for medical insurance so that you won’t need to spend your own money to see the doctor.” I was so surprised that I could enjoy such benefits in the US.

Other participants also referred to difficulties in obtaining information about the medical and insurance system, such as who to approach or contact to find out more about the process of reimbursement for medical expenses.

ID02: I didn’t know which agencies I should communicate with to solve the medical expense problems. The medical system in the USA is different from that in China. Because of lack of knowledge, I went through many winding roads, spent a lot of money that shouldn’t be spent, and felt very stressful.

Navigating the healthcare and medical system was a challenge faced by many of our participants. This challenge may have knock-on effects such as distress, financial burden, and potential health consequences. For example, participants wrote about how insurance issues, or the lack of knowledge, delayed their treatment and consequently influenced their health.

ID25: It was because of the insurance, I had to wait (several months) to have the surgery. The tumor has grown a lot during that time. After the surgery, (the cancer) was already in its second stage; (as a result) the whole left breast was cut off.

ID07: I had known that I had a tumor on my left breast since long time ago…I didn’t know about the cost to see a doctor in the USA. I didn’t know how to apply for medical insurance either and I didn’t dare tell others about my disease. Year after year I became frightened; the disease can be fatal after a long time.

Particularly, any delay caused in undergoing treatments can potentially have serious and harmful health effects.

Lack of Available Social Support in a Foreign Country

Some participants lived in the USA alone, with other family members still living in their home countries. Therefore, they lacked access to social support. One participant (ID02) wrote about feeling lonely and helpless when she was diagnosed, because she had no relatives in the country to approach for support. She described herself as being “soaked in tears every day.” The absence of family members in the USA seemed to have negative effects on how the participants coped with their diagnosis and treatment.

Discussion

The current study analyzed the participant essays produced during a previous expressive writing study [21, 22]. Expressive writing allowed participants to disclose private thoughts and feelings, especially when they encountered cultural and linguistic barriers to inhibit them from doing so. By using this method, researchers could gain insights into the lived experiences and needs of the Chinese American breast cancer survivors, which may not have been shared or discussed openly otherwise [19]. This study revealed the social needs and challenges of Chinese American breast cancer survivors in two major domains: culturally unique issues and the difficulties related to being an immigrant. In the culture domain, survivors experienced role conflict, stigma, and difficulties in disclosure in particular to significant others. As immigrants, they encountered language barriers, received inadequate social support, and perceived a lack of knowledge of the health insurance and medical system in the USA.

In essence, the culturally unique issues were associated with identity. As Chinese women, their distress was strongly linked to cultural expectations and norms, while their identities remained strongly rooted in this culture. Their concerns were centered on role fulfillment, emotional expression, stigma, and reluctance to disclose cancer diagnosis and negative emotions. These concerns reflect the emphasis of relational goals over individual goals and the emphasis of harmony over intimacy in Chinese culture [4, 31]. Being brought up in a patriarchal society, Chinese women assumed their cultural role as a major caregiver in the family [29, 30]. However, feelings of burdening the family and incapability of fulfilling family responsibilities are sources of distress among the women and hindered disclosure of diagnosis and support seeking. These cultural issues were present from their diagnosis, throughout treatment, and remained after therapy had ended. These concerns are shared with other groups of Asian American breast cancer survivors [8, 16].

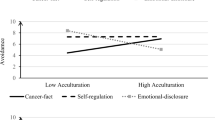

Tensions regarding emotional expression in Chinese women were further illustrated in the parent study [22]. It was found that breast cancer survivors benefited more so, in terms of increased well-being and quality of life, from writing instructions that prompted the cognitive reappraisal of stressful events (i.e., self-regulation and cancer-fact writing) than they did from those prompting emotional processing (i.e., emotional disclosure writing). Culturally, Chinese Americans tend not to willingly talk openly about cancer survivorship experience. Thus, their emotions and thoughts related to cancer might have been suppressed and undisclosed. Lu and colleagues proposed that the expressive writing may therefore have been a therapeutic experience [22]. Asian cancer survivors may need further training and support to (a) effectively cope with negative emotions and (b) address barriers encountered in relation to expressing emotions.

Not seeking familial support seemed to be due to the feeling of burdening others, whereas, for non-family or community members, stigma seemed to be the reason to not utilize social support resources. This study showed that in addition to negative appearance, beliefs that “cancer is contagious” contribute to perceived stigma in Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Stigma reduces social support seeking and increases social avoidance [32, 33]. Stigma is also associated with fear of social rejection and lowered psychological well-being [34,35,36]. Chinese, or Asian, survivors may not seek support because they are afraid of inviting others’ criticism or negative feedback (e.g., stigma) or they do not want to bring their problems to others [37]. Addressing cancer-related stigma among Chinese people would potentially facilitate adaptation and rehabilitation among Chinese cancer survivors. Future research should examine methods (e.g., education) to reduce cancer-related stigma in Chinese American communities.

The challenges that they faced as immigrants may stem from a lack of knowledge and support. Living in a foreign country sets additional barriers for patients’ healthcare seeking. Even though all participants had lived in the USA for many years, they still perceived language barriers and unfamiliarity with the healthcare and insurance system. These barriers made receiving (informational and social) resources and support difficult before, during, and after treatment. Limited proficiency in English hinders Chinese breast cancer survivors to actively seek useful medical information about cancer diagnosis, treatment options, and rehabilitation after treatments. A lack of knowledge about the healthcare and insurance system, which is partly attributed to English proficiency, also poses difficulties for these breast cancer survivors to obtain access to medical services for which they are eligible to utilize with lower costs [4]. Chinese women who did not actively navigate the American healthcare system did not practice effective breast examinations, regardless of how many years of formal education they received [38]. Living in a country with a substantially different medical system, Chinese breast cancer survivors need extra informational support in their seeking of medical service in the USA.

This study contributed to the literature because of its unique sample and methodology. First, previous studies primarily used face-to-face interviews or focus groups to understand the needs and challenges among Asian cancer survivors. However, some participants might not feel comfortable to freely express their concerns to their interviewers and peers. For example, participants described that their negative experiences with others made them feel stigmatized, embarrassed, ashamed, and lacking in support from loved ones. Since Chinese culture discourages expression of emotion that may harm the groups’ harmony [28], these negative experiences and feelings may not have been shared outside of the anonymous writing context. In the prior study, participants were asked whether they had shared what they wrote with others. Sixty-nine percent of them reported that they did not tell other people [21]. These results suggested that expressive writing allows participants to reveal their emotions and private thoughts that they had kept to themselves. The current study provides a sensitive method to capture survivors’ concerns by utilizing this expressive writing approach. Expressive writing at a home setting is more private than traditional qualitative methods, and participants can express their deepest feelings. Participants were also asked to write in their native language, which removes language barriers for expression of feelings and experiences. The success is indicated by participants’ revelation of true feelings and thoughts during the writing sessions.

Second, qualitative analyses in three iterated phases were used to capture cultural meanings of participants’ writings conducted in Chinese. Implicit linguistic expressions like analogies, metaphors, and Chinese idioms were common in written essays. Phrases used in the writings would have lost their meaning without considering culture and its use of analogies and metaphors. For example, one participant discusses her “many winding roads” to describe their difficulties when navigating the healthcare system, and another participant talks about the scars on her body as “centipedes crawling.” Differences between Chinese and English linguistic structures would make the use of currently available analytical packages less useful for qualitative analysis. Instead of translating essays into English and using software package, trained Chinese-English bilingual and bicultural coders conducted line-by-line analysis to capture themes with cultural significance that might be lost in initial translation. Bilingual and bicultural coders also assisted with difficult translations which were not directly translatable or had lost their meaning, but the meanings could be described in similar or equivalent words or idioms by the coders.

Third, this study highlighted the interrelationships among different needs of Chinese American breast cancer survivors as well as tracing the needs to their culture. Cultural beliefs and norms from their home country are still deeply rooted in immigrants, and thus, culture guides their behavior. For example, cultural norms and gender roles can influence patients’ interpersonal dynamics with their spouses, family, and friends. The lack of knowledge affects their medical decision making and behavioral changes during recovery. Furthermore, being an immigrant also adds additional barriers to the utilization of health services and rehabilitation. With less support available from extended family, Chinese immigrant breast cancer survivors experience dual sources of stress in adjusting to cancer.

This study has some limitations that must be noted. First, although the expressive writing approach allows for in-depth disclosure of feelings and thoughts, it lacks the systematic investigation and further probing commonly done in structured interviews and focus groups. Second, this study used convenience sampling instead of purposive sampling due to secondary data analysis. Therefore, the lived experiences of the participants may be specific to these women and not representative of all Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors. Future studies with a more representative sample and systematic expressive writing approach are warranted to investigate the relationships found in this study.

Future Directions and Implications

Our findings have direct implications for future interventions and services for Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors. To fulfill the information needs of this population, services are recommended to provide more effective patient education in their native language. Education brochures printed in Chinese can be delivered to medical offices and communities to provide easily accessible information about health insurance in the USA as well as some facts and myths about breast cancer (e.g., screening, diagnosis, potential causes and treatment for breast cancer). These brochures can be tailor-made by incorporating cultural beliefs and addressing myths about cancer so that health-promoting behavior, such as screening, can be increased and stigma can be reduced.

The study suggests a number of concerns among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Professional counseling sessions can add components to target these concerns about stigma and communication among family members. For families of Chinese breast cancer survivors, future family-centered interventions may include sessions that facilitate discussion about the potential needs of patients; this may help family members be more psychologically prepared for the patient’s life changes while adapting to cancer and to encourage help-seeking from different resources when necessary. As few medical and mental health professionals are bilingual and bicultural, education and psychosocial intervention programs that target Chinese American breast cancer survivors to address the needs discussed above may be best delivered by Chinese community agencies that have strong ties with, and are trusted by, immigrants.

Moreover, findings from this study point to the following future research directions. First, little is known about how stigmatization about cancer influences adjustment among Asian cancer survivors. A previous study found that education and peer mentor support helped Chinese American breast cancer survivors, possibly through the reduction of stigma [39]. Future interventions focusing on stigma reduction may be particularly fruitful. Second, Chinese breast cancer survivors’ relational concerns for their family suggest that future studies should focus on both patients’ and their family’s adjustments to the disease (e.g., exploring the needs and challenges of caregivers, and communication between caregivers and patients, mutual adjustment between Chinese couples). The lack of health insurance and unfamiliarity with healthcare system suggest that future work should improve information and relevant services for Chinese breast cancer survivors.

In conclusion, this study revealed multiple aspects of social issues and needs among Chinese immigrant breast cancer survivors through an expressive writing approach. Participants indicated their reluctance to disclose diagnosis, stigma, lack of social support, and concerns for fulfillment of multiple roles. Related to life in the USA, participants encountered language barriers and felt unfamiliar with the local healthcare system. These findings shed light on the potential research and practical implications for a better course of recovery among the underserved Chinese breast cancer survivors living in the USA.

References

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi:10.3322/caac.21208.

Liu L, Zhang J, Wu AH, Pike MC, Deapen D. Invasive breast cancer incidence trends by detailed race/ethnicity and age. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(2):395–404. doi:10.1002/ijc.26004.

Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. The psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study of the shared and unique needs of younger versus older survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(3):177–89. doi:10.1002/pon.710.

Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12:38–58.

Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW. Predicting physical quality of life among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):789–802. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9642-4.

Wen KY, Fang CY, Ma GX. Breast cancer experience and survivorship among Asian Americans: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(1):94–107. doi:10.1007/s11764-013-0320-8.

Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Hasan S, United States Bureau of the Census. The Asian population: 2010. Suitland: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2012. Available at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/dec/c2010br-11.html.

Ashing KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(1):38–58. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030.

Chen YC. Chinese values, health and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(2):270–3. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01968.x.

Lee S, Chen L, Ma GX, Fang CY, Oh Y, Scully L. Challenges and needs of Chinese and Korean American breast cancer survivors: in-depth interviews. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;6(1):1–8. doi:10.7156/najms.2013.0601001.

Lim J-W, Gonzalez P, Wang-Letzkus MF, Ashing-Giwa KT. Understanding the cultural health belief model influencing health behaviors and health-related quality of life between Latina and Asian-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(9):1137–47. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0547-5.

Gibson MA. Immigrant adaptation and patterns of acculturation. Hum Dev. 2001;44(1):19–23. doi:10.1159/000057037.

Tsai TI, Morisky DE, Kagawa-Singer M, Ashing-Giwa KT. Acculturation in the adaptation of Chinese-American women to breast cancer: a mixed-method approach. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(23–24):3383–93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03872.x.

Wong-Kim E, Sun A, Merighi JR, Chow EA. Understanding quality-of-life issues in Chinese women with breast cancer: a qualitative investigation. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 2):6–12.

You J, Lu Q. Sources of social support and adjustment among Chinese cancer survivors: gender and age differences. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(3):697–704. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2024-z.

Wellisch DK, Kagawa-Singer M, Reid SL, Lin YJ, Nishikawa-Lee S, Wellisch M. An exploratory study of social support: a cross-cultural comparison of Chinese-, Japanese-, and Anglo-American breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8(3):207–19.

Kagawa-Singer M, Wellisch DK, Durvasula R. Impact of breast cancer on Asian American and Anglo American women. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1997;21(4):449–80. doi:10.1023/A:1005314602587.

Quach T, Nuru-Jeter A, Morris P, Allen L, Shema SJ, Winters JK, et al. Experiences and perceptions of medical discrimination among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients in the Greater San Francisco Bay Area, California. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):1027–34. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300554.

Sue DW, Sue D. Counseling the culturally diverse: theory and practice. Hoboken: Wiley; 2012.

Lu Q, Yeung NC, You J, Dai J. Using expressive writing to explore thoughts and beliefs about cancer and treatment among Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2015; doi:10.1002/pon.3991.

Lu Q, Zheng D, Young L, Kagawa-Singer M, Loh A. A pilot study of expressive writing intervention among Chinese speaking breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):548–51. doi:10.1037/a0026834.

Lu Q, Wong CCY, Gallagher MW, Tou RYW, Young L, Loh A. Expressive writing among chinese american breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2017;36(4):370–379. doi:10.1037/hea0000449.

Giorgi A. The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. J Phenomenol Psychol. 1997;28(2):235–60. doi:10.1163/156916297X00103.

Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books; 1963.

Else-Quest NM, LoConte NK, Schiller JH, Hyde JS. Perceived stigma, self-blame, and adjustment among lung, breast and prostate cancer patients. Psychol Health. 2009;24:949–64.

Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, Glaser R, Emery CF, Crespin TR, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: a clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3570–80.

Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, Oppedisano G, Gerhardt C, Primo K, et al. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: processes of emotional distress. Health Psychol. 1999;18:315–26.

Bond MH. Emotions and their expression in Chinese culture. J Nonverbal Behav. 1993;17(4):245–62. doi:10.1007/BF00987240.

Gabrenya WKJ, Hwang KK. Chinese social interaction: harmony and hierarchy on the good earth. In: Bond MH, editor. The Handbook of Chinese Psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 309–21.

Ho DYF. Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In: Bond MH, editor. The Handbook of Chinese Psychology Hong Kong. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 155–65.

Kagawa-Singer M, Wellisch DK. Breast cancer patients’ perceptions of their husbands’ support in a cross-cultural context. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(1):24–37. doi:10.1002/pon.619.

Peters-Golden H. Breast cancer: varied perceptions of social support in the illness experience. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:483–91. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(82)90057-0.

Fredette SL. Breast cancer survivors: concerns and coping. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18:35–46.

Crandall CS, Moriarty D. Physical illness stigma and social rejection. Br J Soc Psychol. 1995;34(8):67–83. doi:10.1080/08870440802074664.

Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. Br Med J. 2004;328:1470–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C.

Lam WWT, Fielding R. The evolving experience of illness for Chinese women with breast cancer: a qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(2):127–40. doi:10.1002/pon.621.

Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Culture and social support. Am Psychol. 2008;63(6):518–26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.

Chen WT. Predictors of breast examination practices of Chinese immigrants. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(1):64–72. doi:10.1097/01.NCC.0000343366.21495.c1.

Lu Q, You J, Man J, Loh A, Young L. Evaluating a culturally tailored peer mentoring and education pilot intervention among Chinese breast cancer survivors using a mixed methods approach. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(6):629–37.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the American Cancer Society MRSGT-10-011-01-CPPB (PI: Qian Lu).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee, and the authors’ institutional ethics committee approved the study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the expressive writing parent study.

Funding

This study was supported by the American Cancer Society MRSGT-10-011-01-CPPB (PI: Qian Lu).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warmoth, K., Cheung, B., You, J. et al. Exploring the Social Needs and Challenges of Chinese American Immigrant Breast Cancer Survivors: a Qualitative Study Using an Expressive Writing Approach. Int.J. Behav. Med. 24, 827–835 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9661-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9661-4