Abstract

Childhood trauma has been described as a public health crisis, thus calling for solutions at multiple levels and across child-serving contexts. Consistent with ecological systems theory, individual experiences of trauma are nested within wider contexts of influence that can result in collective and systemic experiences of trauma. Given that schools are an important child-serving context, there is need to attend to the ways that schools can contribute to both problems and solutions. In this chapter, we offer a wide focus lens to interventions for students exposed to trauma through a definition of trauma as within and across individual, collective, and systemic levels. We describe how much of the extant literature on school-based trauma intervention has targeted the individual student level, with increased expansion that integrates an ecological perspective to trauma intervention. Trauma-informed schools hold promise as a mechanism for promoting systemic resilience and disrupting systemic trauma. School mental health research and practice must enable trauma-informed schools that are culturally responsive and healing-centered across child, school, and community contexts.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

In this chapter, we offer a wide focus lens to interventions for students exposed to trauma through a definition of trauma as within and across individual, collective, and systemic levels. We describe how much of the extant literature on school-based trauma intervention has targeted the individual student level, with increased expansion that integrates an ecological perspective to trauma intervention.

Nature and Impact of the Problem

Childhood trauma has been described as a public health crisis (e.g., Blaustein, 2013; Magruder et al., 2017), necessitating attention to addressing trauma at the individual level as well as the contributing systems. Campaigns to raise awareness that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can lead to serious negative consequences for children have propelled terms such as toxic stress to everyday language in child-serving settings such as schools. Important distinctions, however, should be noted in that ACEs are inclusive of childhood adversities but do not represent all possible adversities that might be experienced, particularly exposures that occur at collective or systemic levels. For example, the original ACEs study (Felitti et al., 1998) contained items focused on individual exposure in areas such as physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. Expansion to community-level adversities did not appear in the literature until over a decade later, in work such as the Philadelphia ACEs (e.g., Chronholm et al., 2015).

Related, exposure to adversities in childhood does not mean trauma will be experienced. Rather, childhood trauma can be an outcome of exposure to different forms of adversities. In 2014, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provided the seminal definition of trauma, as follows:

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. (p. 7)

To highlight the defining features of trauma, McGlynn-Wright and Briner (2021) expand on the three critical elements of this definition: the event, the experience, and the effects (SAMHSA, 2014). First, the event can vary a great deal to include an acute, singular event (e.g., severe car accident), a series of exposures to the same type of event (e.g., chronic child abuse) or to different events over time (e.g., cumulative exposure), and/or complex exposure to multiple and severe adverse events (Overstreet & Mathews, 2011). Second, the experience of the event involves the harmful interruption of safety (i.e., sense of physical, psychological, emotional security), agency (i.e., sense of independence and control over actions and consequences), dignity (i.e., sense of one’s place and power), and belonging (i.e., sense of connection and group membership). Third, the long-lasting effects of the event occur when coping is overwhelmed and/or the experience of the event cannot be integrated with one’s sense of self or beliefs about the world. Additional factors determine whether exposure to adversities will result in trauma, including individual interpretations of and reactions to the event. As described by Chafouleas et al. (2019), individual interpretations and reactions are influenced by conditions including the history of trauma exposure, personal factors (e.g., coping style, maturity, psychological history), and environmental factors (e.g., support resources, social connections). The individual interpretations and reactions intersect with features of the adverse exposure such as predictability, duration, intensity, and consequences, which together both influence and inform directions for intervention. Taken together, the complexities of the definition of trauma make clear the importance of understanding that trauma intervention is not one size fits all.

Related, it is important to understand why exposure to ACEs as potentially traumatic events is problematic. Two central reasons include the magnitude of exposure and resulting consequences from adverse childhood experiences. Exposure to trauma is common for children around the globe, with a substantial proportion experiencing adversities such as natural disaster, armed conflict, and other humanitarian emergencies (Magruder et al., 2017). In a recently released report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019) noted that at least one in six adults in the United States experienced four or more adverse childhood experiences, with estimates that five of the top ten causes of death can be linked to adverse childhood experiences. The report goes further to note that preventing adverse child experiences could have an impact on population health, such as large reductions in the number of health conditions as well as reductions in health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking) and socioeconomic challenges (e.g., school dropout, unemployment).

The ever-mounting evidence regarding substantial and life course outcomes associated with exposure to childhood adversities points to the need for proactive and prevention-focused efforts that begin in childhood. And in fact, exponential growth in policy, practice, and research agendas has been witnessed over the past decade (Chafouleas et al., 2021). As we elaborate in the next section, however, the overall body of work as applied within education settings may best be described as emerging and heavily focused on trauma-specific intervention, meaning supports delivered at the individual level to remediate maladaptive symptoms. Although individual approaches can lead to improved outcomes, the positive impacts of trauma-based approaches are expanded when the intended beneficiary extends beyond the individual student to include the systems in which adversities are experienced. In this way, the problem-solving lens becomes ecologically focused, with intervention decisions informed by understanding which components of an intervention may be most relevant and effective in producing durable outcomes. Some situations may call for trauma-specific intervention delivered to individuals with a focus on teaching strategies that promote adaptive interpretation and reaction. Other situations may require system-level efforts to remove, minimize, or neutralize trauma exposure, and another approach might focus on skill-building of others (e.g., adults) in the environment to reduce actions that could re-traumatize individuals (Chafouleas et al., 2019).

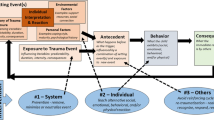

McGlynn-Wright and Briner (2021) referenced these levels, or targets for trauma intervention as individual, collective, and systemic (see Fig. 6.1). Consistent with ecological systems theory, individual experiences of trauma are nested within wider contexts of influence that can result in collective and systemic experiences of trauma. Collective trauma, also referred to as communal trauma, refers to a traumatic experience that is shared with a community or group of people, which can range from a family or whole society (Weems & Overstreet, 2008). The community microsystem may be defined by features such as geography, kinship, and/or shared identity. Collective trauma within one microsystem can disrupt connections with others, and thus also have an impact on mesosystems (Weems & Overstreet, 2008). Collective trauma can include current or past situations and experiences such as natural disasters and the genocide of specific groups of people based on racial or ethnic characteristics (e.g., slavery, genocide of Native Americans, September 11 terrorist attacks, COVID-19). When collective trauma occurs based on one’s social identity, community members may experience compounding effects of discrimination, racism, and oppression (Brave Heart et al., 2011). Communities impacted by collective trauma are often overwhelmed by their inability to address their own needs, which creates uncertainty and distress (Hobfoll et al., 2007).

An ecological lens to trauma: different levels and across time. (Note: Adapted from McGlynn-Wright & Briner, 2021)

Individual and collective trauma can be fueled by systemic trauma, which occurs through formal and informal social structures and policies (exosystem) and cultural ideologies (macrosystem). The nature of systemic trauma can change over time (chronosystem). An example of current systemic trauma is the disproportionate COVID-19 mortality rates for Black and Latinx populations due to societal inequities in health care and socioeconomic resources, which are linked to systemic racism; examples of historical systemic trauma include slavery and the holocaust.

In summary, the application of an ecological lens to view trauma offers directions for broader impact of trauma interventions. Re-framing trauma as something that occurs not only at the individual child level but also with attention to communal experiences of trauma and to the societal structures that perpetuate trauma extends the focus of intervention. With regard to school settings, interventions for students exposed to trauma mean a focus on not only the student but also student populations, educators, and school policies. This wide focus lens affords dual benefit as it not only can strengthen intervention match (i.e., components of intervention strategy are selected and targeted based on need), but also can result in synergistic effects that reduce risk across individual, collective, and systemic levels. Next, we offer expanded discussion on this multi-level focus for trauma intervention.

Focus of Trauma Intervention

In the previous section, we presented that trauma occurs, has impact on, and should be addressed at multiple levels. Thus, it is important to align possible foci for intervention across each of these levels. In this section, we provide background on and propose targets for treatment at three levels as applied to education settings: (a) individual trauma, (b) collective trauma, and (c) systemic trauma focused on school personnel and the larger school microsystem.

Before diving into application of multi-level targets of trauma intervention within schools, however, two points are foundational. First, the tenets of trauma-informed schools are necessary for school personnel to begin to identify and respond to students’ trauma experiences and symptoms (Chafouleas et al., 2016). Professional learning is needed to facilitate trauma-informed knowledge and attitudes as well as the opportunity to build skills through positive practice and feedback in applying trauma-informed practices. Second, as school professionals move to address the needs of students exposed to trauma, they must understand that individual trauma experiences are not randomly distributed or acontextual—they are nested within collective and systemic trauma experiences driven by structural inequities and systemic racism within society and within our schools (Saleem et al., in press). In fact, Goldsmith et al. (2014) propose that a “systemic [trauma] paradigm is necessary to accurately reflect the complex cultural, cognitive, behavioral, and institutional systems in which trauma occurs (p. 125).” In other words, it is important to consider conditions that contribute to or impede incidence of adverse childhood experiences and trauma. There is a need, for example, to intentionally acknowledge and address how racism and other forms of social oppression are systemically ingrained within institutions such as schools, which can influence youth’s experiences with and healing from trauma. This acknowledgment includes recognition that youth from historically marginalized backgrounds can experience trauma based on aspects of their identity (e.g., race, sex, class, gender) at individual, collective, and systemic levels (e.g., Alessi & Martin, 2017), with race being particularly salient in schools (e.g., Jernigan & Daniel, 2011; Saleem et al., 2019). With these two points in mind, we review the foci for trauma intervention broadly and at individual, collective, and systemic levels. See Table 6.1 for a summary. Note that our review is not meant to provide an exhaustive list, but instead offers primary targets based on evidence-based trauma practices and supporting literatures on forms of social oppression in the experience of trauma.

As has been reviewed, many trauma treatments take an individual approach with a focus on symptom reduction. These interventions provide individuals with skills to regulate emotions as well as evaluate and increase helpful thoughts, helpful behaviors, and adaptive coping skills (e.g., Cohen et al., 2009; Kar, 2011). These skills allow for increased control and autonomy in managing consequences of trauma, which are important given that traumatic experiences are often outside of one’s control and can lead to debilitating consequences (e.g., feeling helpless, hopeless, anxious). A core principle of treating trauma through an individualized lens is that those who have experienced trauma can learn better ways of coping, which can both relieve their symptoms and improve day-to-day functioning in their lives (SAHMSA, 2014). Thus, major components for addressing trauma at the individual level generally include reducing individual psychological symptoms, regulating emotions, and altering negative cognitions. Other essential components include promoting safety, healthy relationships, and building trust (e.g., Cohen et al., 2009; Kar, 2011).

As previously noted, collective trauma is often the result of cumulative and devastating losses and is linked with negative psychological consequences (Luszczynska et al., 2009; Somasundaram, 2014). Targets to address collective trauma can vary based on the scale (e.g., society, community, family; Ainslie, 2013; Somasundaram, 2014). For example, a large-scale collective trauma intervention may be focused on re-constructing communities, re-establishing social norms, and/or providing economic support. These strategies are often implemented from entities such as government departments or international nongovernmental organizations (Somasundaram, 2014). Collective trauma can also be addressed at a community level, with primary components that include restoring connectedness, social support, and sense of collective efficacy (Hobfoll et al., 2007). Points of intervention also might include empowerment, reducing stigma and isolation, addressing historical and unresolved grief, building local resources and capacities, and increasing support systems (Brave Heart et al., 2011; Somasundaram, 2014). Collective trauma examples that can impact students could include school shootings (e.g., Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida), natural disasters (e.g., Hurricane Katrina), or race-based killings that lead to communal mourning or loss of morale (e.g., 2020 heightened racial unrest after the Killing of George Floyd).

Addressing trauma at the systemic level requires attention to institutions, practices, policies, and contextual factors that perpetuate, maintain, invalidate, or produce trauma (Goldsmith et al., 2014). For example, in some settings youth’s trauma triggers or traumatic stress reactions may be mislabeled and misunderstood leading to penalization or stigmatization (Saleem et al., 2019). Although less frequently studied, there are several targets for systemic intervention. First, it is essential to identify, acknowledge, and alter bias policies and practices that are insensitive to youth’s mental health needs and are discriminatory or convey devaluation based on aspects of one’s identity (e.g., race, sex, class, gender). Next, providing comprehensive training to individuals in power within systems to improve knowledge and change bias attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors is important—in particular, trainings that focus on self-reflection, increasing staffs’ awareness and skills to analyze systems of inequality, and making space to discuss how to create change within these systems (Almeida et al., 2007). Additionally, adults who work with youth would benefit by learning about the multiple ways that trauma can impact students and themselves (Borntrager et al., 2012). Next, we explore possible approaches to trauma intervention at different levels as applied in education settings.

Approaches to Trauma Intervention in Schools

Trauma intervention must include focus not only on remediation of trauma symptoms but also on strengths-based approaches that bolster resilience. Just like exposure to trauma, the resilience of individuals is nested within collective and systemic resilience. Intervention approaches must therefore attend to the individual and the collective of the school population, as well as the school personnel, policies, and practices that are part of the systems that define the school. As previously described, however, approaches used by schools to date have been focused on individual students exposed to trauma, with a systematic review reporting that only 7% of the literature on trauma-informed care in schools provided evidence of a multi-tiered approach (Berger, 2019). Others have noted a lack of attention to the school’s role in perpetuating systems of oppression and exposure to trauma as well as a lack of attention to student and community strengths to collectively heal the effects of trauma and challenge the systemic inequities that perpetuate trauma (Avery et al., 2020; Gherardi et al., 2020; Saleem et al., in press). Thus, our goal in this section is to offer suggestions for the integration of trauma-informed approaches with other established or emerging strengths-based approaches that promote healing and foster well-being across individual, collective, and systemic levels. A summary is provided in Table 6.2, which includes broad approaches by level (individual, collective, systemic) along with specific examples of potential developing and adapting school mental health interventions. In addition, example measures are included in Table 6.2 that could be used to assess outcomes, which are roughly organized into proximal and medial/distal indicators. We purposefully draw attention to outcome measures given that establishing desired outcomes should be the first step in the intervention selection process.

Approaches to Individual Trauma

As discussed throughout, the earliest and primary efforts to address the needs of students exposed to trauma focused on the development of school-based trauma-focused treatments. These treatments target students whose trauma reactions align with specific mental health disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. When delivered in schools, these treatments have demonstrated medium to large effects in the reduction of traumatic stress reactions (Chafouleas et al., 2016). Although individualized and group-based targeted interventions can be effective for reducing student distress, an exclusive focus on treating symptoms can perpetuate a deficit-focused approach. Treating clinical symptoms is important; however, there is also a need for approaches designed to focus more broadly on overall health and well-being within a whole child lens (Chafouleas & Iovino, 2021).

Contemplative practice is an example of a strength-based approach to working with students exposed to trauma that focuses on asset-building rather than deficit reduction. Contemplative practices, including meditation and mindfulness, move beyond traditional interventions to equip students with the skills to increase awareness, insight, and emotional regulation (Waters et al., 2015) to bring forth “…their own genuine way of connecting their heart and mind” (Grossenbacher & Parkin, 2006, p. 1). Empowering students with the autonomy to make meaning of their experiences and set their own goals for healing and growth can contribute to overall well-being and a sense of purpose in life (Ginswright, 2018). In their systematic review, Waters et al. (2015) found that contemplative practices demonstrated positive effects on self-awareness, self-regulation, and social competence, the building blocks for a healthy sense of self and success in school and in life (Jones & Kahn, 2017).

School Mental Interventions to Address Individual Trauma

As noted in Table 6.2, we include two primary categories of interventions to address the individual trauma level: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) strategies and contemplative practices.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Strategies

Cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) strategies are among the most robust evidence base for intervening in individual and small groups of students experiencing a maladaptive response to trauma exposure (Dorsey et al., 2017). CBT-based approaches for trauma with substantial evidence supporting their effectiveness include Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT; Cohen et al., 2006) and Cognitive Behavioral Interventions for Trauma in Schools (CBITS; Jaycox et al., 2012). These core CBT intervention packages have also been extended to expand both the student populations receiving intervention and providers able to deliver the interventions. One example is Bounce Back (Langley et al., 2015), which incorporates elements of TF-CBT and CBITS and is designed for young students aged 5–11 years. In addition, Jaycox et al. (2009) adapted CBITS into Supports for Students Experiencing Trauma (SSET), which can be delivered by school staff without clinical training. For a more detailed description of these cognitive-behavioral intervention approaches and relationships to student outcomes, see the 2019 review provided by Chafouleas and colleagues.

Contemplative Practices

Contemplative practices, which may include mindfulness approaches and meditation practices, can both decrease trauma symptomatology and improve emotional regulation (Waters et al., 2015). Although used interchangeably, contemplative practice often focuses on meditation and associated techniques such as visualization and transcendental approaches whereas mindfulness may combine meditation with other strategies such as breathing exercises, body scans, and yoga (Waters et al., 2015). The review by Waters and colleagues (2015) includes a summary of contemplative practices including loving kindness meditation, mindfulness, transcendental meditation, breathing instruction, and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). In addition, some contemplative and mindfulness practices may be movement-based such as progressive muscle relaxation, yoga, and Tai Chi (Ortiz & Sibinga, 2017; Sibinga et al., 2015; Waters et al., 2015).

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reviewed the effects of mindfulness and contemplative approaches (Klingbeil et al., 2017; Ortiz & Sibinga, 2017; Zenner et al., 2014; Zoogman et al., 2015). Although results are promising, some limitations are noted in informing working with students with trauma exposure. First, the reviews differed in how they defined contemplative and mindfulness approaches. For example, Zenner et al. (2014) excluded mindfulness approaches that included relaxation techniques (such as progressive muscle relaxation and visualization) whereas these approaches were included in other reviews (Waters et al., 2015). In addition, only one study included evaluation of methodological rigor or used it as inclusion criteria (Klingbeil et al., 2017). Perhaps most relevant, it is important to note that only one of these reviews focused on studies that delivered intervention to students with trauma exposure. Ortiz and Sibinga (2017) focused specifically on MBSR as an intervention to reduce adverse impacts of trauma, finding that these strategies were associated with decreased impairment and improved resilience and positive outcomes across several studies.

Approaches to Collective Trauma

Collective trauma is likely to be experienced in geographic or kinship communities oppressed by structural inequality and discrimination based on characteristics such as race, sex, gender identity, or religion. The shared impact of these experiences on the community, even when not directly experienced by each individual who identifies with that community, represents collective trauma. Experiences of collective trauma, such as COVID-19 (especially in communities of color), police killings of unarmed people of color, or violence against members of the LGBTQ community, can result in a collective sense of endangerment, community disorder, and profound fracture in the trust of societal institutions for members of the affected communities (Keynan, 2018). When communities are deprived of opportunities for healing from a collective trauma, the impacts of that trauma can be long-lasting (historical) and transmitted across generations (intergenerational) (Brave Heart et al., 2011; NCTSN, 2017).

Collective trauma calls for collective healing, which can occur when individuals with a shared identity have opportunities to support one another and draw on their solidarity to promote healing and growth (Drury et al., 2019). Social and emotional learning (SEL) curricula can provide those opportunities in schools. Effective use of social and emotional learning curricula can create safe, supportive school environments that are conducive to learning and to the development of positive relationships with peers and adults (Jones & Kahn, 2017). Healing-centered approaches take those opportunities to the next level by centering culture within social and emotional learning and empowering students to be agents in fostering well-being (Ginwright, 2018). Healing-centered approaches to SEL integrate culturally responsive practices to help students build an awareness of justice and inequality and generate strategies to resist social oppression (Jagers et al., 2019), which can contribute to overall well-being, hopefulness, and optimism (Blitz et al., 2016; Potts, 2003; Prilleltensky, 2003).

School Mental Health Interventions to Address Collective Trauma

As presented in Table 6.2, we include two primary categories of interventions to address collective trauma: transformative social-emotional learning and cultural adaptations to evidence-based intervention.

Transformative Social Emotional Learning

Emerging as an opportunity to integrate trauma-informed approaches and social-emotional learning, transformative social-emotional learning offers potential to promote equity and collective growth. Developed by Jagers et al. (2019), transformative social-emotional learning positions student social-emotional development as occurring through expansion of typical programming to account for life experiences and emerging identities that shape self-understanding and connections with others (Chafouleas et al., 2021). Jagers et al. (2019) focused on issues of race and ethnicity in development, yet it has potential to address a range of inequities through anchoring in justice-oriented citizenship.

Using the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning’s (CASEL’s) framework of core social and emotional competencies (i.e., self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, responsible decision-making), Jagers et al. (2019) extend learning each competency from typical focus on personal responsibility to participatory and transformative concepts. For example, personal self-management may include components such as emotion-focused coping and agency (resilience, social efficacy) whereas transformative self-management may include problem-focused coping and cultural humility (agency, resistance, moral, civic efficacy, collective efficacy). The approach taken to each concept varies. For example, personal responsibility focuses on individual development and participatory may include class community-building, multicultural education, and/or service learning. In contrast, a transformative approach may include culturally relevant education, project-based learning, and/or youth participatory action research. As noted, the transformative pieces have alignment with trauma-informed principles, and have potential to extend to addressing collective trauma.

Faculty at CASEL (n.d.) are working to refine social and emotional learning into transformative social and emotional learning as a lever for equity and social justice, defining it as:

a process whereby young people and adults build strong, respectful, and lasting, relationships that facilitate co-learning to critically examine root causes of inequity, and to develop collaborative solutions that lead to personal, community, and societal well-being. This form of SEL is aimed at redistributing power to promote social justice through increased engagement in school and civic life. It emphasizes the development of identity, agency, belonging, curiosity, and collaborative problem solving within the CASEL framework.

Cultural Development and Adaptations to Evidence-Based Intervention

In acknowledgment that the vast majority of evidence-based interventions have been developed and evaluated without attention to application across different contexts, some researchers have advocated for and found evidence to support racial–ethnic and cultural development and adaptations (Marsiglia & Booth, 2015; Nierkens et al., 2013). Goodkind et al. (2010), for example, adapted CBITS for use with adolescents identifying as American Indian, with focus on feasibility and appropriateness in addition to typical indicators of symptomology. The authors share their process for participatory engagement in co-determining adaptations to materials, presenting a summary table of modifications to each session. Participatory engagement involved co-determining changes as well as numerous community-based presentations with many different stakeholders. As one example, the authors noted making a range of modifications “… such as removing inadvertently offensive, Eurocentric examples of cognitive restructuring, as well as deep structure changes such as utilizing stories and examples based upon participants’ cultural teachings, collective experiences, and addressing differing cultural beliefs about how long it is acceptable to talk about someone after they have died” (Goodkind et al., 2010, p. 5).

Although burgeoning, there are some promising approaches that can be utilized and extended to address collective trauma. Key to cultural development and adaptation success is engaging participatory methods that facilitate co-determination of choices. Participatory methods include engaging communities in acknowledging, addressing, and healing from factors contributing to the collective trauma(s). With regard to adaptations, modifications can be surface (e.g., modify delivery mode or materials) and/or deep structure (e.g., incorporating cultural beliefs about how trauma affects health). It is important to evaluate whether the collective trauma (i.e., the event, experience, effects) warrants an adapted approach compared to a newly developed and tailored treatment.

Approaches to Systemic Trauma

Systemic trauma is perpetuated by policies and practices implemented by institutions that result in trauma (Goldsmith et al., 2014). Schools must acknowledge their responsibility as a source of trauma for some students and families—ranging from Native American boarding schools to school segregation to contemporary discipline policies characterized by zero-tolerance, exclusionary, and shaming discipline practices (NCTSN, 2017). Schools have the potential to transform themselves from a source of systemic trauma to a source of systemic resilience by adopting practices and policies that promote healing and dismantle systems of privilege, discrimination, and oppression that result in inequities for students of color and other marginalized groups (Saleem et al., in press).

A first step in shifting policies and practices to promote systemic resilience is increasing staff awareness of the structural inequities and systemic racism within society and within our schools that contribute to experiences of trauma for students of color (Temkin et al., 2020). Although most approaches for trauma-informed schools focus on increasing staff knowledge about trauma and trauma-informed approaches (Avery et al., 2020; Temkin et al., 2020), few contextualize that knowledge within the legacy of historical and intergenerational trauma or ongoing race and class bias (Blitz et al., 2016). As Gherardi et al. (2020, p. 492) noted, trauma-informed schools “…need to reattribute responsibility for the outcomes associated with social marginalization from the victims to the systems” to become a source of systemic resilience for students. Conceptualizing trauma from a socio-ecological perspective lays the groundwork for changes in school practices that support healing and promote equity. Change in classroom practices is unlikely to be a successful change agent in the absence of an infrastructure to reinforce and encourage new practices (Temkin et al., 2020).

School policies must support educational equity that promotes healing and avoids the re-traumatization of students. As noted by Avery et al. (2020), policy changes related to discipline are often seen as a key feature of systemic approaches to addressing trauma. In their review, discipline changes focused on moving away from punitive, reactive discipline and moving toward strength-based and skill-building discipline strategies that focus on maintaining relational connection, developing self-regulation skills, and supporting time in class. When schools enact these types of discipline changes to address the disproportionate impact of harsh and exclusionary discipline on students of color, success in achieving that goal must be documented by disaggregating disciplinary data to ensure the intended effect (Gherardi et al., 2020).

Systemic resilience also requires adoption of practices and policies that support the well-being of school personnel given their central role as agents of change across various models of trauma-informed schools. For example, when a teacher’s well-being is threatened due to work-related stressors, they may lack sensitivity to student needs, be more likely to disengage and withdraw from their students, have difficulty making effective changes to classroom management practices to address emerging student needs, and be more likely to employ exclusionary discipline practices (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Specific consideration of secondary traumatic stress (STS) is important because the highly interpersonal nature of the work of school personnel paired with their efforts to form meaningful relationships with individual students and families mean there are ample opportunities to learn about student traumatic experiences through their daily interactions. Learning about the traumatic experiences of the students they work closely with can lead school personnel to experience secondary traumatic stress symptoms—thus serving to contribute to collective trauma in the whole school population. These mirror the classic symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder that can develop when trauma is directly experienced, such as intrusive thoughts, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal (Hydon et al., 2015). Thus, there is a need to attend to the psychological needs of school personnel who have frequent interactions with students and are impacted by students’ trauma. Given the documented psychological consequences of secondary traumatic stress for school personnel, it is essential for staff to learn about the multiple ways that trauma can impact both students and themselves (Borntrager et al., 2012). Further, staff need support for managing secondary traumatic stress that is embedded within the school context to promote resilience and coping (Caringi et al., 2015). Primary tools for reducing secondary traumatic stress include providing open and supportive opportunities to discuss secondary traumatic stress, integrating stress-reduction activities throughout the school day (e.g., access to mindfulness tools), and increasing resources to help staff manage secondary traumatic stress (e.g., peer groups, connect with community-based support) (Hydon et al., 2015).

School-Based Interventions to Address Systemic Trauma

We include two primary categories of interventions to address systemic trauma: examining policies and promising alternatives to exclusionary discipline, and interventions to prevent and respond to secondary traumatic stress. See Table 6.2. We acknowledge that the categories are not mutually exclusive and likely result in greatest impact through co-occurrence. For example, altering exclusionary policies that contribute to racial disparities and utilizing school-wide restorative justice practices (Teasley, 2014) can be combined with workforce development strategies that allocate funding to training aimed to address trauma and foster equitable and justice-centered schools (Blitz et al., 2016; Dutil, 2020).

Promising Alternatives to Exclusionary Discipline

Given the serious negative outcomes that result from exclusionary discipline, recent reviews have sought to identify promising alternatives to current school discipline practices (see Chafouleas et al., 2020). Many individual alternatives have been identified across reviews, which can be grouped into four broad categories: (1) data-based inquiry for equity and to inform policy change, (2) positive behavior interventions and supports, (3) inclusive approaches for problem-solving behavior concerns, and (4) supportive and culturally relevant practices. Using school discipline data to inform school improvement and positive behavior interventions and supports is consistent with the application of prevention science in schools, commonly referred to as multi-tiered systems of support. Embedding inclusive approaches for problem-solving behavior such as restorative practices, reintegration of students after conflict or absence, and conflict resolution within these alternatives has shown increased use in schools. Given generally higher familiarity with the first three alternatives and how they might be used in combination, we focus here on additional description of supportive and culturally relevant practices.

Effectively addressing trauma and the systems level involves becoming aware of not only “trauma” specifically but also how systemic inequality in our society and schools perpetuates and exacerbates trauma exposure (Saleem et al., in press). For example, this may involve providing explicit instruction to staff on implicit/unconscious bias. Although there is a wealth of research related to unconscious bias, there is little research on applying unconscious bias training to schools (Dee & Gershenson, 2017). Preliminary evidence, however, suggests that training related to empathetic discipline and unconscious bias is associated with decreases in measures of implicit bias (Whitford & Emerson, 2019) and decreases in exclusionary discipline (Okonfua et al., 2016). Another promising approach, which requires training for school staff on classroom practices that seek to minimize discriminatory discipline in schools, is Culturally Responsive Classroom Management (CRCM; Weinstein et al., 2003). This approach, which is aligned with culturally responsive pedagogy, provides school staff with tangible and concrete practices to improve their classroom environment, including activities that help them recognize their own cultural biases, techniques to develop awareness of broader social, economic, and political contexts impacting students, and ideas for building relationships with students based in trust.

In addition to training on addressing systemic inequities in our schools and addressing unconscious bias, school leaders can also provide explicit training to promote trauma awareness and the use of trauma-informed practices. As noted in a recent review, this work typically focuses on improving staff trauma knowledge, attitude, behavior, and practice (KAPB: Lowenthal, 2020). This review also noted that these initiatives to improve “Trauma-Informed Care” fall on a continuum of their scope and intensity—from “limited change” initiatives (typically involving a one-time training for staff) to “comprehensive” change initiatives involving staff training with ongoing support and coaching and long-term plans for systems-level changes to practices, policy, and climate. Results of this review indicated that training initiatives involving a “one off” training session for staff were unlikely to lead to sustained changes over time or actual changes in practice (Lowenthal, 2020). Although there is some preliminary evidence connecting one-time trauma-informed training with changes in attitude to trauma-informed care that are sustained over time (Parker et al., 2020), there is limited evidence that these changes in attitudes are associated with changes in practice (and thus changes in student outcomes) without additional support and coaching.

These findings indicate school leaders seeking to develop trauma-informed systems likely need comprehensive approaches to improve staff KAPB related to trauma-informed care (Dorado et al., 2016). For example, in their evaluation of implementation of multi-tiered trauma-informed systems, von der Embse et al. (2019) conducted an initial whole staff professional development training on trauma-informed practices, and then followed this training with intensive coaching for a small set of teachers to support implementation of target strategies. In addition, this initial training was associated with changes in trauma-based assessment and intervention delivery across the district, reinforcing the practices and concepts introduced during the training.

Interventions to Prevent and Respond to Secondary Traumatic Stress

Another important component of trauma intervention targeting the systems level is preventing and responding to secondary traumatic stress (STS). Much like trauma-informed work, STS has received increased attention. A recent review (Sprang et al., 2019) found that the STS literature is stymied by differing definitions and conceptualizations. Although additional empirical study is needed, these authors identified promising strategies as including psychoeducation, mindfulness, emotional regulation strategies, and cognitive-behavioral strategies (e.g., redirecting automatic thoughts, cognitive restructuring). One strategy with specific evidence relevant to schools is mindfulness, with a recent meta-analysis (Klingbeil & Renshaw, 2018) indicating medium effect for outcomes related to psychological well-being, psychological distress, and physiological indicators, as well as small effects on classroom climate and instructional practices. It is important to note, however, that their review focused on general mindfulness intervention and was not specifically directed to examining impact of mindfulness on STS.

In addition, it should be noted that much of the STS work has focused on improving staff individual well-being and self-care practices (Sprang et al., 2019). Although this is important, this focus tends to minimize organizational factors contributing to STS (Sprang et al., 2019). Therefore, a systems-level conceptualization of responding to STS is essential; one such approach with initial promising evidence is the Secondary Traumatic Stress Informed Organizational Assessment (STSI-OA; Sprang et al., 2014) and Toolkit (Sprang et al., 2018). This intervention is based on best practices related to STS and implementation science to identify organizational supports that will create and sustain system-wide change. This approach involves initially completing the STSI-OA based on the organization’s current approach to prevention and intervention of STS to identify priority domains of intervention (resilience, safety, policies, leader practices, organizational practices). Based on the results of the STSI-OA, the accompanying toolkit can be used to identify activities and procedures that correspond with the targeted domains for intervention. Aligned with best practices in implementation science, this intervention also identifies “implementation drivers” for competency, organizational factors, and leadership within each domain to support sustained change over time.

Summary and Future Directions in Trauma Intervention

As emphasized throughout this chapter, the past decade has brought tremendous steps forward in acknowledging and recognizing impacts of adverse childhood experiences. Substantial efforts have been undertaken to build an evidence base for trauma-informed intervention that targets trauma at the individual level. Directions forward must connect related literatures and expand focus to be inclusive of collective and systemic levels of intervention. As related to school mental health research and practice, a key emphasis must be on fostering education settings that engage a trauma-informed lens that is culturally responsive and healing-centered for the whole child, school, and community (Chafouleas et al., 2021). By definition, trauma-informed schools are a mechanism to promote systemic resilience and to disrupt the systemic trauma that is often perpetuated by schools. Yet gaps in how to fully engage this mechanism are evident, such as defining and measuring expected impacts with clear ties to educational outcomes, establishing capable school personnel who are supported in doing the work, and integrating knowledge on racial and cultural stress into frameworks. Agendas forward must move to define, enable, and sustain the “whole package” of a trauma-informed approach in schools.

References

Ainslie, R. C. (2013). Intervention strategies for addressing collective trauma: Healing communities ravaged by racial strife. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 18(2), 140–152.

Alessi, E. J., & Martin, J. I. (2017). Intersection of trauma and identity. In Trauma, resilience, and health promotion in LGBT patients (pp. 3–14). Springer.

Almeida, R., Vecchio, D. D., & Parker, L. (2007). Foundation concepts for social justice-based therapy: Critical consciousness, accountability, and empowerment. In E. Aldarondo (Ed.), Advancing social justice through clinical practice (pp. 175–206). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Avery, J. C., Morris, H., Galvin, E., Misso, M., Savaglio, M., & Skouteris, H. (2020). Systematic review of school-wide trauma-informed approaches. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1–17.

Baker, C. N., Brown, S. M., Wilcox, P. D., Overstreet, S., & Arora, P. (2016). Development and psychometric evaluation of the attitudes related to trauma-informed care (ARTIC) scale. School Mental Health, 8(1), 61–76.

Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: A systematic review. School Mental Health, 11, 650–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09325-0

Blaustein, M. E. (2013). Childhood trauma and a framework for intervention. In E. Rossen & R. Hull (Eds.), Supporting and educating traumatized students: A guide for school-based professionals (pp. 3–21). Oxford University Press.

Blitz, L. V., Anderson, E. M., & Saastamoinen, M. (2016). Assessing perceptions of culture and trauma in an elementary school: Informing a model for culturally responsive trauma-informed schools. The Urban Review, 48(4), 520–542.

Borntrager, C., Caringi, J. C., van den Pol, R., Crosby, L., O'Connell, K., Trautman, A., & McDonald, M. (2012). Secondary traumatic stress in school personnel. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5(1), 38–50.

Brave Heart, M. Y. H., Chase, J., Elkins, J., & Altschul, D. B. (2011). Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282–290.

Caringi, J. C., Stanick, C., Trautman, A., Crosby, L., Devlin, M., & Adams, S. (2015). Secondary traumatic stress inpublic school teachers: Contributing and mitigating factors. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 8(4), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2015.10801_23

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, November). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Preventing early trauma to improve adult health. CDC Vital Signs. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/ACEs/

Chafouleas, S. M., & Iovino, E. A. (2021). Engaging a whole child, school, and community lens in positive education to advance equity in schools. Frontiers in Psychology.

Chafouleas, S. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., & Christ, T. J. (2009). Direct behavior rating (DBR): An emerging method for assessing social behavior within a tiered intervention system. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34, 195–200.

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health, 8, 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Chafouleas, S. M., Koriakin, T. A., Roundfield, K. D., & Overstreet, S. (2019). Addressing childhood trauma in school settings: A framework for evidence-based practice. School Mental Health, 11(1), 40–53.

Chafouleas, S. M., Briesch, A. M., Dineen, J. N., & Marcy, H. M. (2020). Mapping promising alternative approaches to exclusionary practices in U.S. schools. UConn Collaboratory on School and Child Health. Available from http://csch.uconn.edu/

Chafouleas, S. M., Pickens, I., & Gherardi, S. A. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Translation into action in K12 education settings. School Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09427-9

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children. Guilford Press.

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Deblinger, E., & Berliner, L. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents. Guilford Press.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (n.d.). Transformative SEL as a lever for equity & social justice. Retrieved March 23, 2021, from https://casel.org/research/transformative-sel/

Cronholm, P. F., Forke, C. M., Wade, R., Bair-Merritt, M. H., Davis, M., Harkins-Schwarz, M., et al. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 354–361.

Dee, T., & Gershenson, S. (2017). Unconscious bias in the classroom: Evidence and opportunities. Google’s Computer Science Education Research.

Dorado, J. S., Martinez, M., McArthur, L. E., et al. (2016). Healthy environments and response to trauma in schools (HEARTS): A whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. School Mental Health, 8, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0

Dorsey, S., Mclaughlin, K. A., Kerns, S. E. U., Harrison, J. P., Lambert, H. K., Briggs, E. C., et al. (2017). Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46, 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220309

Drury, J., Carter, H., Cocking, C., Ntontis, E., Tekin Guven, S., & Amlôt, R. (2019). Facilitating collective resilience in the public in emergencies: Twelve recommendations based on the social identity approach. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 141.

Dutil, S. (2020). Dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline: A trauma-informed, critical race perspective on school discipline. Children & Schools, 42(3), 171–178.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., & Edwards, V. J., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

Gherardi, S. A., Flinn, R. E., & Jaure, V. B. (2020). Trauma-sensitive schools and social justice: A critical analysis. The Urban Review, 52, 482–504.

Ginwright, S. (2018). The future of healing: Shifting from trauma-informed care to healing centered engagement. https://medium.com/@ginwright/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c

Goldsmith, R. E., Martin, C. G., & Smith, C. P. (2014). Systemic trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 117–132.

Goodkind, J. R., Lanoue, M. D., & Milford, J. (2010). Adaptation and implementation of cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools with American Indian youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 858–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2010.517166

Grossenbacher, P. G., & Parkin, S. S. (2006). Joining hearts and minds: A contemplative approach to holisticeducation in psychology. Journal of College and Character, 7(6), 1–13.

Hales, T., Kusmaul, N., Sundborg, S., & Nochajski, T. (2019). The Trauma-Informed Climate Scale-10 (TICS-10): A reduced measure of staff perceptions of the service environment. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 43(5), 443–453.

Hobfoll, S. E., Watson, P., Bell, C. C., Bryant, R. A., Brymer, M. J., Friedman, M. J., et al. (2007). Five essential elements of immediate and mid–term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 70(4), 283–315.

Hydon, S., Wong, M., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., & Kataoka, S. H. (2015). Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(2), 319–333.

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): Toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162–184.

Jaycox, L. H., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., Wong, M., Sharma, P., Scott, M., & Schonlau, M. (2009). Support for students exposed to trauma: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 1, 49–60.

Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S. H., Stein, B. D., Langley, A. K., & Wong, M. (2012). Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 28, 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799f19

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525.

Jernigan, M. M., & Daniel, J. H. (2011). Racial trauma in the lives of Black children and adolescents: Challenges and clinical implications. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4(2), 123–141.

Jones, S. M., & Kahn, J. (2017). The evidence base for how we learn: Supporting students’ social, emotional, and academic development. National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, The Aspen Institute.

Kar, N. (2011). Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 7, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S10389

Keynan, I. (2018). The memory of the holocaust and Israel’s attitude toward war trauma, 1948–1973: The collective vs. the individual. Israel Studies, 23, 95–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.2979/israelstudies.23.2.05

Klingbeil, D. A., & Renshaw, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for teachers: A meta-analysis of the emerging evidence base. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(4), 501–511.

Klingbeil, D. A., Fischer, A. J., Renshaw, T. L., Bloomfield, B. S., Polakoff, B., Willenbrink, J. B., et al. (2017). Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on disruptive behavior: A meta-analysis of single-case research. Psychology in the Schools, 54(1), 70–87.

Langley, A. K., Gonzalez, A., Sugar, C. A., Solis, D., & Jaycox, L. (2015). Bounce back: Effectiveness of an elementary school-based intervention for multicultural children exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 853–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000051

Lowenthal, A. (2020). Trauma-informed care implementation in the child-and youth-serving sectors: A scoping review. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Resilience, 7(1), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.7202/1072597ar

Luszczynska, A., Benight, C. C., & Cieslak, R. (2009). Self-efficacy and health-related outcomes of collective trauma: A systematic review. European Psychologist, 14(1), 51–62.

Magruder, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., & Elmore Borbon, D. L. (2017). Trauma is a public health issue. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1375338. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1375338

Marsiglia, F. F., & Booth, J. M. (2015). Cultural adaptation of interventions in real practice settings. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514535989

McGlynn-Wright, T., & Briner, L. (2021, March 30). Integrative trauma and healing framework. Retrieved from https://intheworksllc.squarespace.com/inflections/2021/3/30/integrative-trauma-and-healing-framework.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Schools Committee. (2017). Creating, supporting, and sustaining trauma-informed schools: A system framework. National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Nierkens, V., Hartman, M. A., Nicolaou, M., Vissenberg, C., Beune, E., Hoster, K., van Valkengoed, I. G., & Stronks, K. (2013). Effectiveness of cultural adaptations of interventions aimed at smoking cessation, diet, and/or physical activity in ethnic minorities. A systematic review. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073373

Okonofua, J. A., Paunesku, D., & Walton, G. M. (2016). Brief intervention to encourage empathic discipline cuts suspension rates in half among adolescents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(19), 5221–5226. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523698113

Ortiz, R., & Sibinga, E. M. (2017). The role of mindfulness in reducing the adverse effects of childhood stress and trauma. Children, 4(3), 16.

Overstreet, S., & Mathews, T. (2011). Challenges associated with exposure to chronic trauma: Using a public health framework to foster resilient outcomes among youth. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 738–754.

Parker, J., Olson, S., & Bunde, J. (2020). The impact of trauma-based training on educators. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 13(2), 217–227.

Potts, R. (2003). Emancipatory education versus school-based prevention in African American communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1/2), 173–183.

Prilleltensky, I. (2003). Understanding, resisting, and overcoming oppression: Toward psychopolitical validity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1/2), 195.

Saleem, F. T., Anderson, R. E., & Williams, M. (2019). Addressing the myth of racial trauma: Developmental and ecological considerations for youth of color. Journal of Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00304-1

Saleem, F. T., Howard, T., & Langley, A. (in press). Understanding and addressing racial stress and trauma in schools: A pathway toward healing and resilience. Psychology in the Schools.

Sibinga, E., Webb, L., Ghazarian, S. R., & Ellen, J. M. (2015). School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT. Pediatrics, 137(1), 1–8.

Somasundaram, D. (2014). Addressing collective trauma: Conceptualizations and interventions. Intervention, 12(1), 43–60.

Sprang, G., Ross, L., Blackshear, K., Miller, B., Vrabel, C., Ham, J., Henry, J., & Caringi, J. (2014). The secondary traumatic stress informed organization assessment (STSI-OA) tool. University of Kentucky Center on Trauma and Children, #14-STS001, Lexington, Kentucky.

Sprang, G., Ross, L., Miller, B. C., Blackshear, K., & Ascienzo, S. (2017). Psychometric properties of the secondary traumatic stress–informed organizational assessment. Traumatology, 23(2), 165–183.

Sprang, G., Ross, L. A., & Miller, B. (2018). A data-driven, implementation-focused, organizational change approach to addressing secondary traumatic stress. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare, 6(1), 62–68.

Sprang, G., Ford, J., Kerig, P., & Bride, B. (2019). Defining secondary traumatic stress and developing targeted assessments and interventions: Lessons learned from research and leading experts. Traumatology, 25(2), 72.

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual (2nd ed.). ProQOL. Retrieved from ProQOL.org

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. 14-4884). Retrieved from http://store.samhs a.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884/SMA14-4884.pdf

Teasley, M. L. (2014). Shifting from zero tolerance to restorative justice in schools. Children & Schools, 36(3), 131–133.

Temkin, D., Harper, K., Stratford, B., Sacks, V., Rodriguez, Y., & Bartlett, J. D. (2020). Moving policy toward a whole school, whole community, whole child approach to support children who have experienced trauma. Journal of School Health, 90(12), 940–947.

von der Embse, N., Rutherford, L., Mankin, A., & Jenkins, A. (2019). Demonstration of a trauma-informed assessment to intervention model in a large urban school district. School Mental Health, 11(2), 276–289.

Waters, L., Barksy, A., Ridd, A., & Allen, K. (2015). Contemplative education: A systematic, evidence-based review of the effect of meditation interventions in schools. Educational Psychology Review, 27, 103–134.

Weems, C., & Overstreet, S. (2008). Child and adolescent mental health research in the context of Hurricane Katrina: An ecological-needs-based perspective and introduction to the special section. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 487–494.

Weinstein, C., Curran, M., & Tomlinson-Clarke, S. (2003). Culturally responsive classroom management: Awareness into action. Theory Into Practice, 42(4), 269–276.

Whitford, D. K., & Emerson, A. M. (2019). Empathy intervention to reduce implicit bias in pre-service teachers. Psychological Reports, 122(2), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118767435

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 603.

Zoogman, S., Goldberg, S. B., Hoyt, W. T., & Miller, L. (2015). Mindfulness interventions with youth: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(2), 290–302.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chafouleas, S.M., Saleem, F., Overstreet, S., Thorne, T. (2023). Interventions for Students Exposed to Trauma. In: Evans, S.W., Owens, J.S., Bradshaw, C.P., Weist, M.D. (eds) Handbook of School Mental Health. Issues in Clinical Child Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20006-9_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20006-9_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-20005-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-20006-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)