Abstract

This paper attempts to provide additional light on the structure and dynamics of inequality of opportunity among Tunisian children during the period 2005–2010. The main steps involved in the analysis comprise: estimation of the Human Opportunity Index, assessment of the relative contributions of circumstances, and decomposition of variations in inequality of opportunity in factors driving them across time and space. The results reveal reasonable and declining levels of inequality in access to some basic services at the national level, but increasing inequalities between regions with inland area lagging the rest of the country. The number of siblings, parents’ education and wealth and location of residence are key factors causing such disparities. Without more inclusive and pro-poor policy actions, there are few chances for children belonging to the less advantaged circumstance groups to spring out of the poverty and inequality lived by their parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Tunisia has been considered for a long period as a model of growing economic performance in Africa and the Arab world, with notable economic growth and remarkable resilience to external shocks and crisis. Yet these achievements have been eclipsed by the slow response of poverty and inequality indicators. During the period 2000–2010, the 3.5% annual growth rate in GDP was accompanied by a decline in poverty rate of about 17 percentage pointsFootnote 1 (Bibi et al. 2011). Despite this remarkable decline, poverty in Tunisia remains considerably high compared with some countries from the two sides of the Mediterranean.

Inequality in Tunisia, as well in others developing countries, is no longer regarded as a key prerequisite for growth, but a twin blow to prospects for alleviation poverty, entailing less economic growth and less pro-poor growth (Ravallion 1997; Chambers and Krause 2010; UNDP 2013). The wellbeing cost of inequality is expected to be even higher associated with different inter-group disparities, which imply intergenerational transmission of inequities and self-perpetuation of poverty, generating social tensions and conflicts in a society (Stewart and Langer 2008; Kabeer 2010). In general, rural-urban disparities and inter-regional gaps may lead to social and political instability as happened recently in Tunisia in 2008 and 2011.

The lion’s share of the literature on equity and social justice is focused largely on inequality of outcomes, which is restricted to income or consumption inequality. Yet, inequality of outcomes is regarded as a mixture of inequality of effort and inequality of opportunity. Then strategies and policies for equating outcomes may be accompanied by discouragement of people to invest and innovate. The differentiation between inequality of opportunities (chances) and inequality of outcomes can be specifically useful for public policy. It’s well recognized that equality of opportunity is not only fundamental, but also a critical precondition for prosperous and stability of a society. Inequality of opportunity isoriginated from disparities in circumstances and broadly regarded unfair and lacks the attention of policy makers. As argued by Roemer (1998, 2014), Bourguignon et al. (2007) and Ferreira and Gignoux (2011), lack of access to basic services and resources deprives large parts of the society of their capabilities. Such inequality of opportunity may discourages people to take a greater effort to fill the gap and therefore induces wasted productive potentials.

As such, a number of studies that deal with inequality issues reveal that risks related to human and cognitive development are not homogeneously distributed over the life-cycle. They are typically higher in earlier stages of life (childhood), with considerable long-term and occasionally irreversible consequences. It is well established in the early childhood literature that access to basic services in the first years of life is crucial to wellbeing later in life periods. Inadequate access, for instance, to water and sanitation services hampers a child’s subsequent cognitive and physical development, leading to adverse productivity and wellbeing outcomes that mostly persist into adulthood. The first years of a child’s life are crucial for equality of opportunity as physical, cognitive, and psychological developmentoccurs early in child life and any developmental deficits that occur in early childhood may be permanent (UNESCO 2006). In other words, early years of child life are sensitive to the conditions in which a child lives and also represent a time when individuals have the least control over their circumstances (Assaad et al. 2012). Being born to a poor or illiterate parents, or living in an underprivileged region, is entirely outside of a child’s control, but it may affects negatively the child’s wellbeing and could determine his or her entire life course. As stated by Heckman (2006), children from disadvantaged backgrounds diverge generally from their more advantaged peers somewhat early in their development, and gaps may persist throughout life. It’s well recognized that inequality of opportunity observed during the childhood can be an important contributor to the observed inequality later in life.

In Tunisia, as elsewhere, many of the critical inputs for early childhood development, such as early education and access to safe water and sanitation are unevenly distributed among children from different regions. For instance, Tunisian children and youth who represent more than 25% of the population (UNPD 2013), face a lot of problems such as poverty and lack of access to healthcare and education particularly in unprivileged regions. The gap has been enlarged during the recent decades between regions. The uneven distribution of basic housing services and educational opportunities contributes consecutively to the inequality in desirable early childhood development outcomes, and, as such, plays a key role in inequality later in life (de Barros et al. 2009). Following this, further consideration should be accorded to the important role played by some circumstances for which a child should not be held responsible for the lack of access to certain services. Despite the importance of this topic few studies have focused, thus far, on inequality of opportunity among children in Tunisia, except the recent works of Jemmali and Amara (2015, 2017).

Giving the importance of equality of opportunity in poverty alleviation and inclusive development, the current study attempts to analyze the level and dynamics of inequality in access to certain basic services among Tunisian children during the period 2005–2010. For this purpose it uses the Human opportunity index’s (HOI) methodology and data from the two national surveys on Households’ Budget, Consumption and Standard of Living conducted by the National Statistical Institute of Tunisia in 2005 and 2010. In sum, the current study aims to answer to a set of questions: how far a region is from the objective of providing fair and universal access to a set of basic services to all children? And what’s the degree to which each child has an equal opportunity to benefit from those services regardless of his or her circumstances at birth, such as gender, place of birth, and family background? And finally is there any improvement in the equality of opportunities during the five years before the 2011’s uprising?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: The following section presents a brief literature review of major theoretical and empirical contributions to inequality analysis. Section 3 presents the data and empirical methodology used to the assessment and decomposition of the inequality of opportunities. Section 4 presents the main results and Sections 5 and 6 are devoted to discussions and limitations of the study. Conclusion and policy recommendationsare provided in last section.

2 Literature Review

It’s well recognized since Dworkin (1981), Arneson (1989), Cohen (1989), and, to some extent, Sen (1985) that inequality in the distribution of particular outcomes, such as income, is not the appropriate yardstick for measuring the fairness of a considered allocation or social system. Notwithstanding the main differences in nuance, all these influential authors argued that outcome differences attributable to differences in choices for which individuals can be held responsible, may be morally acceptable. In this view, the unacceptable inequalities reside in a logically prior space of resources, capabilities, and opportunities for which individuals haven’t a measure of control. Roemer (1998), for example, identifies those factors over which individuals have a measure of control, as “efforts” (e.g. educational attainment, or how hard one works), whereas those beyond their control are referred to as “circumstances” (e.g. age, gender, or parental socio-economic status). Given this dissimilarity, he characterizes “equality of opportunity” basically as a state in which main outcomes, which he calls “advantages”, are scattered independently of circumstances.

In the recent development economics literature, two modern leading theories of wellbeing and social justice, namely the Capability Approach (Sen 1985, 1999, abbreviated CA) and The Equality of Opportunity Approach (Roemer 1998, abbreviated EOp) risen to be currently deeply influential amongst development scholars and in political spheres. The two approaches are founded both on the philosophical origins in Rawls’ principles for social justice (Rawls 1971, 1999) which are: everyone is entitled to an adequate set of liberties, so long as they are compatible with the same liberties for others; and everyone is entitled to a fair equality of opportunities. Furthermore, the two approaches also coincide in acknowledging that one should goes beyond the simple outcome indicators and rather considers the underlying choice sets and circumstances. Notwithstanding theses similarities, one has to acknowledge that there are notable differences between the two approaches: for instance the CA’s strength relies in helping to understand better what individual wellbeing is, while the EOp contributes greatly to the ways for improving individual wellbeing with justice. In this regard, we should keep in mind that there is a powerful complementarities between the two approaches, as one excels where the other one might come short.

An extensive literature is devoted to the investigation of poverty and inequality in Tunisia (see for example Ayadi et al. (2001, 2003) and Bibi and Duclos (2005)). These studies show significant reduction in extreme poverty and inequality in Tunisia.They reveal, furthermore, that Western regions, especially rural areas, contribute substantially to the overall poverty. Worth to note that these studies are based on a monetary approach using income as the unique indicator of well-being. In this regard, Ayadi et al. (2008) attempted to consider the non monetary approach by using a composite asset index as a proxy of household wealth. They developed a welfare composite index, based on household living conditions and using data from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS)Footnote 2 in order to analyze the poverty trend. Using the decomposable poverty index (Foster, Greer, Thorbecke (FGT)), the authors decomposed poverty by area (urban-rural), by region and by sources (water, toilets, education, communication and housing). In addition, little attention was given to assessing inequality in a wider sense using new multidimensional measures others than the traditional economic inequality indicators such as Gini and Theil indexes.

The first authors who have focused on inequality of opportunities in Tunisia were Jemmali and Amara (2015, 2017). Their studies provided an application of the known Human Opportunity Index (HOI) aimed to assess the inequality in the distribution of basic services (education and housing services) at a regional scale in Tunisia. In their two studies, they found obviously large and significant disparities, particularly in access to safe water and sanitation between the Eastern (Littoral) and Western (Inland) areas. Thanks to the variance decomposition analysis used initially by Son (2013), area of location, socio-economic characteristics of the household head, are found to be the main circumstances driving regional inequality in Tunisia. For the Egyptian case, Ersado and Aran (2014) applied a newly decomposition method based on the concept of Shapely value in cooperative games. In the current study, the same decomposition procedure, developed by Shorrocks (2013), is applied to estimate the contribution of a set of factors.

In their studies, Jemmali and Amara (2015, 2017) used separately the 2005 and 2010 surveys for the estimation of the HOI level without analyzing the extent and the variation of inequality of opportunity between the two years. Following de Barros et al. (2009) who argue that one of the main properties of the HOI is that its changes are additively decomposable,Ersado and Aran (2014) attempted to assess the changes in inequality of opportunity in Egypt during the 2000s. After estimating the level of HOI for each service for 2000 and 2008, they decomposed the variation in the index values by scale and distribution effects and tried to determine the main drivers of the observed changes in equality of opportunities. They point out that any improvement in the value of the index can be caused either by an improvement in the coverage rate (scale effect) or a decrease in the index of dissimilarity (distributional effect).

In a previous study, Assaad et al. (2012) investigated the patterns of inequality of opportunity in child health outcomes in some Arab countries and Turkey using a number of DHS data. They used indicators for stunting or wasting standardized by height and weight of children as outcome variables. Their main results are: total inequality in Egypt is increasing over time and geography is the main widespread circumstance impacting height and weight of children, followed by demographic variables and parents’ education.

Inequality of opportunity in education among children has also attracted recently the attention of a number of researchers. Several cross-country studies that focus on developing countries (e.g. Egypt and Tunisia) such as those of Filmer and Pritchett (1999), Filmer (2005), Smits (2007), and Huisman and Smits (2009), found that socioeconomic status is the main factor affecting access to and achievements in education. Besides, Filmer (2005) pointed out that the prevalence of gender gaps in educational enrollment varies considerably by region across the world. Al-Qudsi (2003) found that household wealth is the important factor impacting school enrollment. Similarly, Zhao and Glewwe (2010) in China and Tansel (2002) in Turkey found same conclusions on the importance of household wealth/income and parents’ education status in affecting a child’s enrollment in school. In this regard, Salehi-Isfahani et al. (2014) focused on inequality of educational opportunities in Egypt, alongside a number of other Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries, using the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) data. They found that parental background variables are the main determinants of inequality in achievement, followed by community characteristics.

3 Data and Methodology

3.1 Data

This study derives its main data from the two national surveys on Households’ Budget, Consumption and Standard of Living conducted by the National Statistical Institute of Tunisia in 2005 and 2010.Footnote 3 The samples in the two surveys are nationally representative and include interviews with 13,392 households representing respectively 0.61% and 0.55% of total households in the country (i.e. 61 and 55 surveyed household are selected respectively in 2005 and 2010, for every 10,000 households). The representative samples are distributed across 1116 districts in both urban and rural areas, belonging to the 24 governorates and the seven economic regions of the country (namely Grand Tunis, North East, North West, Center East, Center West, South East, and South West).

The calculations will be made based on a set of key circumstances and outcome variables derived for all children aged under 18 years living in surveyed households. The considered variables include parents’ education and expenditures, geographic characteristics and access to core basic services. Analysis of educational enrollment (primary and secondary schoolFootnote 4) and attainment is also carried out for specific age groups. Specifically, the empirical analysis will include, on one hand, seven outcome variables: primary school attendance among children aged 6–11 years; lower secondary school attendance among children aged 12–14 years; higher secondary school attendance among children aged 15–18 years; probability of completing the 6th grade on time; probability of completing the 9th grade on time; access to electricity; regular access to safe water; and access to sanitation facilities. On the other hand, the empirical analysis involves seven key circumstances variables:

-

Region: Grand Tunis, North East, North West, Centre East, Centre West, South East, South West (7 categories).

-

Location: large cities, medium and small cities and rural area (3 categories).

-

Household head’s education: None formal education, Primary/Lower secondary, Secondary, Post secondary or equivalent, University, and Postgraduate (6 categories).

-

Spouse’s education: None formal education, Primary/Lower secondary, Secondary, Post secondary or equivalent, University, and Postgraduate (6 categories).

-

Age of Household head: In year (Continuous variable).

-

Gender of Household head: 0 if female and 1 if male (2 categories).

-

Number of siblings aged under 14 years (Discrete variable).

-

Gender of the child: female and male (2 categories).

-

Household consumption per capita (Continuous variable).

Furthermore, the study presents the disparity in access to aforementioned services between the least and most advantaged children and discusses the likelihood of exposure to a set of risk factors and how these circumstances out of the children’s control have an effect on the degree of such exposure.

3.2 Empirical Methodology

As mentioned above, the aim of the study is the estimation and decomposition of the HOI. The index has been first developed and mentioned in the report of the World Bank (2006). Initially applied to Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) by de Barros et al. (2009), the HOI is considered as a very useful measure of the extent to which individual circumstances (birthplace, wealth, gender,...) influence a child’s probability of accessing basic services (e.g. timely education, running water or connection to electricity). It’s notable that the developed index focuses mainly on coverage and inequality in access to core services among children for two main reasons. Firstly, unlike adults, children frequently haven’t the capacity to access to these services by themselves. Thus, access for children could be considered as an opportunity that depends strongly on the family’s circumstances and other factors. Secondly, interventions that aim to reduce inequality between subgroups early in life-cycle (children) are noticeably more cost effective and relevant than interventions done later in life. For all these reasons, an age constraint is included when estimating the HOI for each service.

The HOI combines assessments of both the absolute level of opportunities coverage and how fairly these opportunities are distributed in a society. The index could be defined then as an assessment of the coverage rate of an opportunity discounted by inequality in its distribution across various circumstances groups.Footnote 5 Following de Barros et al. (2009), Son (2013) and Jemmali and Amara (2015, 2017), and given the surveyed random samples of the population, a dichotomous variable zi is created taking a value of 1 if the ith child of the considered group has access to the specific opportunity (for instance safe water and sanitation) and takes a value of 0 if he lacks access to this opportunity. It can be simply proved that E(zi) = pi = P(zi), where pi is the probability that the ith child has access to the considered opportunity. It depends on a set of exogenous circumstances variables related to individual, household, and geographic characteristics behind the child’s control (e.g. gender, parental education and wealth, and geographic location). Before computing the final index, circumstances groups are created as a set of children sharing the same set of characteristics (e.g. male children living in rural areas in the North-Western region, with non-educated parents and five children in the household, or female children, with educated parents and living in rural areas in coastal zones).

Considering the set of predefined k circumstances variables xi1, xi2, …, xik, the probability pi of accessing one of the considered services for the ith child could be estimated by means of a logit model as follows:

The vector of parametersβjis estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The obtained maximum likelihood estimate, \( {\hat{p}}_i \), provides an accurate estimate of the probability of access to a considered opportunity depending on aforementioned circumstances variables. Then, any difference in estimated probability between circumstances groups will be interpreted as an assessment of the inequality of opportunities. After estimating such probabilities, a Dissimilarity index that gives a measure of the dissimilarity of access rates to a given service, is computed as follows (World Bank 2006):

Where \( \hat{D} \) is the estimated relative mean deviation, wi is the population weight which is equal to 1/n with n is the size of the selected sample. \( \overline{p}, \)called level of coverage, is the average prevalence of access to a service in the surveyed sample. It’s calculated using the following formula:

The D-index is used to assess the level of inequality of opportunity which depends on various circumstances. (E = 1 − D) is the measure of the equity of opportunity. As defined above, D takes values ranging between 0 and 1 (0 to 100 in percentage terms). D = 0 means that every child in the society benefits from the same opportunities, while D = 1 means that merely one child in the society benefits from all opportunities.

After estimating the two components: average access to opportunities (\( \overline{p} \)) and D-index (D), the HOI is computed easily as follows:

Since 0 ≤ D ≤ 1, HOI will be necessarily less than or equal to the level of coverage (\( \overline{p} \)), which implies that there will be essentially loss of average opportunities available to all children. The HOI index can be accordingly identified as an inequality-adjusted coverage rate and every policymaker should seek to maximize the HOI by improving total opportunity coverage and boosting equity of opportunity or both coverage and equity.

After computing the HOI level for each outcome variable for the two years 2005 and 2010, it is promising to decompose the variation of the index by scale and distribution effects in order to recognize the main sources of the estimated variations over time (de Barros et al. 2009). The first effect can be defined as a change in the overall coverage for the entire population without any changes in inequality while the second one is defined as a change in the equality of access to the opportunity between the circumstances groups. One of the main properties of the constructed HOI is that variations are additively decomposable. Then, any improvement (increase) in the index value can be attributed either to a rise in the coverage rate (scale effect) or a decrease in the index of dissimilarity, D (equalization effect). Accordingly, the dynamic of the index HOI between 2005 and 2010 can be decomposed into scale and distributional effects for each of the outcome variable as follows:

-

Variationin HOI value:

-

Scale effect:

-

Distributionaleffect:

Furthermore, we seek in the current study to measure the marginal contributions of different circumstances to inequality for the aforesaid bundle of opportunities using the Shapley decomposition procedureFootnote 6 proposed by Shorrocks (2013). It consists of estimating the marginal effect of the HOI, for the two years, after adding or removing each inequality contributor (circumstance) in a specified sequence of elimination (Betti and Lemmi 2008; Shorrocks 2013). The procedure entails computing the marginal impact of each circumstance as all these circumstances are eliminated in succession, and afterward averaging the obtained marginal effects over all the possible elimination sequences. The estimated contribution of all circumstances provides an accurate and additive decomposition between group inequalities (dissimilarity index).

As stated by de Barros et al. (2009), HOI index is dependent on the dissimilarity index (D) (see Eq. 4 above). The value of D index (and therefore HOI) depends on the considered set of circumstances. Note further that HOI and D increases and decreases respectively when more circumstances are taken into account. The impact of adding a circumstance Acan be estimated as follows:

Where N is the set of all the m circumstances; and S is the subset of N circumstances obtained after eliminating the circumstance A (i.e. S does not contain the considered circumstance A). D(S) is the dissimilarity index estimated with the set of circumstances S and D(S ∪ {A}) is the dissimilarity index estimated with set of circumstances S and the circumstance A. Then, using the Shapely procedure, the contribution of the omitted circumstance A to the dissimilarity index can be defined as follows:

Where∑i ∈ NMi = 1, whichmeans that the sum of the contributions of all circumstances to the dissimilarity index adds up to 100%. It’s worth to note in this regard that this property satisfied by the Shapley value decomposition is critical. To assess the marginal effect of each contributor among the seven circumstances on inequality of access to a considered opportunity, the aforesaid procedure is applied on the dissimilarity.

4 Empirical Results

Before delving into the investigation of inequality of opportunity at different scales, a descriptive analysis of how some aforementioned circumstances, beyond the children’s control, may affect the level of access to basic services. The results of this descriptive analysis, shown in Appendix Table 1, are presented at national scale for the two years 2005 and 2010 under each of the two main categories of outcomes: access to main housing services and access to basic education. To highlight the impact of certain circumstances, including the location of residence, on child development outcomes, a comparison of these outcomes is made below between the least and most advantaged children’s groups.Footnote 7

It’s well known in Tunisia that access to basic infrastructure services (i.e. improved drinkable water, sewage facilities and electricity) has considerably expanded in the 2000s, and this expansion has been pro-poor. Based on own calculations on data extracted from the 2005 and 2010 national surveys, the percentage of children aged less than 19 year old living in households benefiting from access to safe water, sanitation facilities and electricity has risen slightly from 41.94% in 2005 to 49.36% in 2010. Despite the overall pro-poor expansion of access to basic services among children, the rate of such expansion differs across regions. The highest expansion, nearly 13%, is observed in the North East, including the Grand Tunis, while the lowest level is observed in the North Western region. In the lagging region, only 33.75% of children (0–18 years), in 2010, benefit from access to basic housing services, compared to 29.89% in 2005.

The Centre Western region is found to experience the lowest percentage of access to basic housing services among children during the five years before the beginning of the 2011’s revolution that took place firstly in this region. Note that the percentage of children in this region with no access to improved water, sanitation facilities and electricity at home has risen from 20.78 to 28.37% during the same period. Despite this slight increase, access to basic services in the inland region remained at low level when compared to other regions. To focus on the origins of this remarkable regional disparity, we use afterward the Shapley decomposition method.

Turning to basic education, the overall likelihood of enrollment is found to be dropped slightly from 94.06 to 93.41% at primary level (ages 6–11), and increased from 59.21 to 66.59% at lower secondary level (ages 12–14), and from 45.65 to 46.53% at higher secondary level during the considered period. Educational attainment rates such as completing the 6th and 9th grades on time,Footnote 8 dropped respectively a little from 35.85 and 45.81% in 2005 to 32.56% and 45.37%in 2010.

To shed more light on the impact of some circumstances on the distribution of educational opportunities at national and regional levels, a comparison is done between the least and most advantaged circumstances groups for the two years 2005 and 2010. The results show that enrollment gap in primary school between the two extreme groups was slightly narrowed during the considered period, indicating a slight pro-poor expansion of enrollment in basic education. The enrollment gap in secondary school (lower and higher levels) was remained high for the two years without considerable improvement in the enrollment rates for the two groups. The highest gap between the two groups of children, observed at the higher secondary level, was dropped slightly from 65.89% in 2005 to 59.86% in 2010. Such large enrollment gap could be considered as an argument of the obvious impact of geographical and family characteristics on access to secondary education in the country. This leads to mention that access to no-primary education that presents for a large part of the population an escape from poverty and unemployment is still restricted to some groups of children depending on some geographical circumstances and family background.

Concerning the educational attainment opportunities, measured by the probabilities of completing the 6th and 9th grades on time, the figure is not different compared to enrollment opportunities at secondary level. The gap between the least and most advantaged groups in completing the primary cycle on time is narrowed slightly from 16.35% point in 2005 to 12.84 in 2010. Otherwise the gap in completing the basic education on time between the two groups was remained high and slightly dropped from 58.78% point to 49.72 during the considered period. Globally, the results reveal no substantial change during the last five years before the 2011’s revolution and high disparity between the two groups particularly in enrollment and attainment in secondary education.

After a preliminary analysis of access to basic services at the national level over the two years, we turn afterward to the assessment and the decomposition of inequality of opportunity in access to these services at both national and regional scales. Starting with the three basic housing services (water, electricity and sewage), a single summary indicator measuring the accessibility of children to these services is used to assess exposure of those children to multiple risk factors; it take 1 if the considered child could access regularly to drinkable water, sanitation facilities and electricity and 0 if not.

At the national scale, the results show high level of coverage and equality indexes, and accordingly higher level of HOI index for access to electricity in the two years. This high level of HOI, more than 90%, indicates that such service is provided more equitably to the majority of households regardless of their circumstances living. Otherwise, the HOIs for access to safe water and sanitation services show lower values at the national scale (around 60% for access to water and less than 40% for access to sanitation facilities); these values are associated with moderate coverage level and low dissimilarity index for access to water and lower coverage level and higher dissimilarity index for access to sanitation. Compared to its neighboring countries, it’s noteworthy to mention that Tunisia takes the lead in the provision of the aforementioned basic services. Over the recent decades, Tunisia has achieved considerable success in expanding access to electricity, water and sanitation services, but challenges remain.

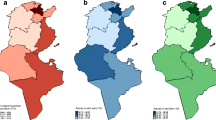

In fact, except for the slight improvement in the coverage (scale effect) and the equality (distributional effect) indexes of access to sanitation services, which had a positive impact on the HOI value, the decomposition of changes in inequality of opportunity for others housing services didn’t showed at the national scale substantial changes during the considered period. Accordingly, it’s easy to conclude that disparities in access to these housing services were persistent across circumstances groups (Fig. 1). The Shapley decomposition results for the two years, presented in the Fig. 2, show that regional variables such as location (urban or rural areas) and region of residence (seven different regions) explain together the lion’s share of the variations in access to housing services; they are found to explain more than 60% of the total variation in access to these services; the remaining part of the variation, about the third, is explained by the rest of explanatory factors (Fig. 2).

Giving the importance of regional circumstances in explaining the inequality in access to housing services, the Fig. 1 shows, in addition, the variation of different inequality indices across regions and time. The figure reveals a huge gap in the HOI values, during the considered period, between regions ranging from 18 to 66% in 2005 and from 11 to 83.61% in 2010. Centre and North Western and South Eastern are shown to be the lagging-regions with scores below 20%, the lowest HOI score, while Grand Tunis is found to be the only region above 50%. Overall, the Fig. 1 reveals that inequality of opportunity in access to safe water and sanitation in inland regions is broadly higher than in the littoral part of the country. The regional average in inland increased slightly from 18% in 2005 to 21% in 2010, while in the littoral region the average increased from 37% in 2005 to 48% in 2010. Concerning the electricity service, one of the main basic housing services, the majority of regions have practically attained universal access, while others, such as some rural areas in the Western part of the country (inland region), show both low coverage and high dissimilarity in the accessibility to this service.

The figure is not so different when we look on how the basic educational opportunities are distributed among children. Five main educational indicators are used in the current study to assess inequality of opportunity in access to different education levels (Primary, Lower secondary and Higher secondary) and basic quality education. The first three services are related to enrollment separately for different levels: (a) the probability of enrollment for children in the age group 6–11 years old in primary; (b) the probability of enrollment for children aged between 12 to 14 years old in preparatory level (lower secondary); and (c) the probability of enrollment for children aged between 15 to 18 years old in higher secondary school education. The fourth and fifth indicators are linked to educational attainment: (d) the probability of completing the 6th grade on time to move from the primary level to the preparatory one; and (e) the probability of completing the 9th grade on time to move from the basic education to the secondary one.

While the HOI for enrollment in compulsory education remained at the same high level, more than 92%, during the considered period, a slight increase of the HOI for enrollment in non-compulsory education (secondary education) is observed over the considered period, jumping from about 55% to over 62% between 2005 and 2010 (Fig. 3a). The improvement in the educational HOI index is due mainly to the proportional improvement in both the level of accessibility to the related educational opportunity and equality in benefiting from this opportunity (Fig. 3a). Unlike the basic education, the HOI for secondary education related to the older age group of (15–18 years old) dropped slightly from about 41.50% in 2005 to under 40% in 2010 (Fig. 3a). This decrease of the HOI is due mainly to a slight decrease of both the coverage (scale effect) and equality (distributional effect) indexes during the considered period. One of the main causes that may explains this decrease of the HOI values is the spread of unemployment among youth. In some regions mainly in the inland part of the country, large number of children who have achieved the basic school level education and living in poor households choose to dropout of schools and search early for a job.

The HOIs for attainment in completing the 6th and 9th grades both decreased over the period, indicating a decrease of about 3% point in the probability of completing the two grades on time. Using these two indicators as measures of the quality of education, the Fig. 3b shows a slight decrease in the quality of primary education due mainly to decrease of both the coverage and equality indexes (negative scale and distributional effects). Besides, a same decrease in the quality of preparatory education due to simultaneous decrease of both the coverage and equality indexes is illustrated in the same Figure.

Similarly to housing services, regional variables (location and region of residence) added to parental education (head’s and spouse’s educational levels) and welfare variable are found to be consistently the most important factors that explain a large part of the variation in enrollment and attainment indicators. For instance, the “region” circumstance explains alone about 40% of the variation in the enrollment rate in the primary school in 2010, while in 2005 the most important factor that explains the large part of variation of the HOI values is the location (urban or rural) with more than 37% of the total variation. Globally, the regional circumstances combined explain over 46% in 2005 and 48% in 2010 of the total variation of enrollment in primary education. While, the family background variables such as age of head of household, parent’s educational attainment, the consumption level of the household and the number of siblings in the family combined explain about half of the variation in enrollment rates, over 80% of the variation in the probability of completing the 6th grade on time and over 50% of the variation in the probability of completing the 9th grade on time. The results of the Shapley decomposition shown in Fig. 4 reveal that parent’s background assessed by educational and economic situation of parents have a considerable impact on their children’s education achievement during the considered period; it affects both the educational attainment and enrollment for different education levels. This means that years of schooling completed, and educational achievement more generally, vary broadly in the society by educational and economic family background.

Turning to regional scale and giving the significant contribution of regional variables in the distribution of educational opportunities shown in the above decomposition analysis, Fig. 3a and b reveal, in addition, the variation of enrollment and attainment HOI indexes across different regions. The figures show that HOI for enrollment in compulsory primary education remained over 90% in all regions during the considered period, indicating that the majority of children from different regions haven’t a problem with access to such education. While access to preparatory school shows significant disparities between littoral and inland regions and a slight improvement during the considered period,. Indeed, the HOI for enrollment in secondary school shows a less disparity between littoral and inland regions and a decrease of the HOI level across all regions (Fig. 3a).

The same figure reveals that the HOI values of the two attainment variables, the probabilities of completing the 6th and 9th grades on time, were decreased in all regions between the two years with a significant disparity between some inland and littoral regions. Indeed, the Center Western region, where the 2011’s revolution has begun, has the lowest level of all the educational HOI (enrollment and attainment) values due to both the less coverage and the high dissimilarity of access to education across children; this region like others in the Western part of the country is very far from universality of access to good quality of education at different levels. In contrast, children, living in the privileged region such as the Capital and their neighbors (Grand Tunis), have more opportunity to access to school and benefit from a good quality of education to get all the required grades on time without repeating years.

5 Discussions

The main findings of the study show that Tunisia experienced a considerable advancement with regards to the availability and access to basic services for children, in some cases with a pro-poor overall effect. Significant improvements have been made particularly in access to sanitation facilities and in lower secondary enrolment rate. The decline in inequality of opportunity in access to these services has been relatively high over the considered period due to both increased coverage (scale effect) and redistribution effects (distributional effect). Yet there are still some areas of persistent and emerging concerns that require urgent interventions related to educational enrollment and attainment opportunities. Indeed, Tunisia experienced during the considered period large disparities across different regions in school enrollment and in education achievement specially at the highest level.

At the regional scale, the results show that wide disparities in access to basic infrastructure persist between the two years, with inland region, particularly the Center Western region lagging the rest of the country. The geographical circumstances (i.e., the residence area) played the main role in these large disparities in housing services. We should keep in mind in this regard that since the French colonial times, the majority of inland region has been underdeveloped compared to the coastal area, called the “Sahel” region. The pre-independence government built main infrastructures in this privileged region, so access to basic services (water and sanitation) in littoral zone was more easier than access in the inland one. Even the Tunisia’s post-independence governments have continued the pattern.

Overall, in line with previous literature in particular with recent studies of Jemmali and Amara (2015, 2017), our results provide further evidence that the gap between the two regions has been enlarged last decades. They emphasized particularly on the key role played by regional factors and background family characteristics on accessing to these basic services. Furthermore, other aforesaid studies which used different measurement methods of wellbeing and inequalities confirmed such regional disparity in Tunisia (Bibi and Duclos 2005; Ayadi et al. 2008).

It’s gleaned from the results that many of the children who living in the inland regions, where the 2011’s revolution occurred, encountered some difficulties in achieving economic and social success which might be embedded to uncontrollable variables like gender, number of siblings, location of birth, and family background. This result is consistent with the finding of many previous studies (e.g. Filmer 2005; Huisman and Smits 2009; Ersado & Eran, 2014) which claimed that family background related variables and the socioeconomic status of parents are the main determinants of inequality and achievement of education in the Middle East and North Africa. Results also show that poor children who mainly living in rural inland areas have had limited access to secondary education due to the high opportunity costs of education at higher level, which left them trapped in a vicious circle of low education and low income. In order to avoid that inequality in educational opportunities may be a cause of poverty and unemployment in Tunisia, educational policies should be redirected to facilitate more access of poor children in unprivileged regions to good an effective education. This requires, as stated by de Barros et al. (2009), not only targeted subsidies to poor children but also measures that would enhance considerably the performance of these children.

6 Limitations of the Study

It is important to denote that the major drawbacks of the current study are linked with the data availability and the HOI method’s limitations. As mentioned previously,the study derives its main data from households surveys which provide relevant information in terms of access to basic services, but they ignore the quality of these services. For instance, different schooling levels might hide large variance in the service quality, while frequent blackouts, high salinity of water may hinder the benefits a children can draw from access to water network services. In line with previous studies, the current analysis is limited to quantitative indicators and exempting the qualitative measurement of access to particularly housing services.

As would be the case for any other measure of inequality, there are some caveats to the D-Index (and therefore the HOI as well), which should be considered primarily by researchers when interpreting the results. The first one is that, by construction, the D-Index is a function of a predetermined set of circumstances and may change if a different set of circumstances is considered. In that case the HOI will be sensitive not only to inequality between circumstance groups which is the key property of the index but also to the subjective selection of circumstances. The second caveat that deserves to be taken into account in future research is related to the sensitivity of the index to inequality. Indeed, the D-Index does not change with redistribution of opportunities among vulnerable (below the coverage rate) or no-vulnerable (above the coverage rate) groups. The other caveat mentioned recently in the literature is that the D indexand the HOI are not subgroup consistent which implies that they cannot be decomposed into similar measures for subgroups of the population. This leads to conclude that the changes in the D index and the HOI over time for the whole population may not be consistent with the variation of the indexes for subgroups of the same population (Dabalen et al. 2015).

7 Conclusions and Recommendations

Concepts like fairness, equity, and justice in the distribution of outcomes are no longer in the realm of philosophers and theorists; rather, they are recently in the forefront of policy design and economic reform. Ensuring children’s access to core basic services such as safe drinkable water, sanitation, electricity and basic education are a crucial step towards justice and fairness in a society. Expanding access to these core services to meet the growing needs of unprivileged population remains an important policy challenge in the economic development process and public policy discussions, including the Millennium Development Goals initiative. It should deserve, furthermore, more attention of academic research community and scholars to combat rising global inequality mainly inequality of opportunity and its negative effects on the society. Whether or not inequality has played a causal role in the 2011’s uprising is difficult to ascertain, but the demand for more equity and inclusion has brought the regional disparities issue to the front burner of the Tunisian governments. In this respect, the current study is concerned with analyzing the level and trends of inequality of opportunity in access to basic education and infrastructure services among Tunisian children during the last quinquennium before the recent revolution.

The analysis was carried out mainly using the HOI methodology, initially developed by the World Bank in 2006, to examine both the coverage and distribution of opportunity in access to basic services. Drawing on micro-data from the two national household surveys carried out by the NIS in 2005 and 2010, we estimate both the HOI values and the contribution of individual socioeconomic and demographic circumstances to inequality of opportunity in accessing the basic services among children aged less than 18 years. The used methodology can be employed as a practical diagnostic tool for policy analysis and an appropriate point of reference for gauging progress in the equality of opportunity thanks to its flexibility for application to various circumstances, opportunities, and population groups. From the perspective of policy makers and research, determining the extent to which circumstances may affect access to a set of basic opportunities related to education (attending the 6th and 9thgrades on time and school enrollment) and housing services (water, sanitation, and electricity) would be helpful in analyzing binding constraints to affording equitable opportunities to all children across regions. In this respect, it’s worth to note that some other key opportunities such as access to basic healthcare and nutrition not included in present study owing to data limitations could be added in other applications.

Globally, advances in basic opportunities in the country are encouraged, but these improvements in coverage and distributional considerations still differ across regions, particularly between inland and littoral zones. In some regions, expansion of access to services has entailed a significant decline in inequality of opportunity, whereas in others, inequality persisted at high levels. There are some practices, successful policies and experiences that permit the coverage be expanded, so more children would benefit, not at the cost of distributional considerations. Taking into account the main findings of the current study, it is notable that targeted interventions and appropriate investments in favor of the less advantaged circumstance groups may afford a significant potential for enhancing overall equity in housing conditions and schooling among children in Tunisia. In this regard a more inclusive approach and special efforts would be required for those children exposed to multiple risk factors. From a policy perspective, evidence indicates that appropriate actions and policies to equalize opportunity between different classes early in the lifecycle are considerably more cost effective and successful than any interventions later in life.

Notes

In 2000, the Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty line (% of population) in Tunisia was 32.4%, in 2010, it decreased to 15.5%.

Despite the high quality of information available at the DHS surveys, they do not contain specific information about household expenditures.

The 2005 and 2010 National Surveys on Households’ Budget, Consumption and Standard of Living can be downloaded from the National Institute of Statistics (www.ins.nat.tn) or from the Economic Research Forum (ERF) open access micro data (www.erfdataportal.com).

Primary education in Tunisia as in the majority of countries provides children with essential reading, writing, and mathematics skills along with an elementary comprehension of such subjects such as history, geography, natural science, social science, art, and music. While the Secondary education (lower and higher levels) completes the provision of basic education acquired at the primary level, and aiming to lay the foundations for lifelong learning and human development, by providing more subject- or skill-oriented instruction using more specialized and educated teachers.

The present section merely gives the basic conceptual method for calculating the Human Opportunities Index. For further details and discussion, refer de Barros et al. (2009) which has a more exhaustive explanation of the procedure for computing the second component of the HOI, the Dissimilarity index (D-index), for estimating inequality of opportunity in access to given services. The methodology used in this section hence follows analogous notations as far as possible in order to retain coherence and comparison.

this method is founded mainly on the concept of Shapley value in cooperative games.

Most and least advantaged groups of children are defined according to circumstances variables. These two groups make up both the two extremes of the set of groups constructed based on circumstances; they account for nearly 3% of the total number of children aged between 0 and 18. The least advantaged group contains children from rural areas, parents (Head and Spouse) with no formal education, in households with more than four children at home, and from families in the poorest quintile class. In contrast, the most advantaged group contains children who are from urban area, parents with higher education level, in households with four or less than four children, and from families in the richest quintile class.

In the current study, we use these indicators as proxies for the measure of the quality of education at primary and lower secondary levels.

References

Al-Qudsi, S. S. (2003). Family background, school enrollments and wastage: Evidence from Arab countries. Economics of Education Review, 22(6), 567–580.

Arneson, R. J. (1989). Equality and equal opportunity for welfare. Philosophical Studies, 56(1), 77–93.

Assaad, R., Krafft, C., Hassine, N. B., & Salehi-Isfahani, D. (2012). Inequality of opportunity in child health in the Arab world and Turkey. Middle East Development Journal, 4(2), 1250006.

Ayadi, M., Matoussi, M. S., & Victoria-Feser, M. P. (2001). Putting robust statistical methods into practice: Poverty analysis in Tunisia. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 3(14), 463–482.

Ayadi, M., Krishnakumar, J., & Matoussi, M. S. (2003). Pooling surveys in the estimation of income and price elasticities: An application to Tunisian households. Empirical Economics, 28(1), 181–201.

Ayadi, M., Ellehga, A., & Chtioui, N. (2008). Poverty in Tunisia: A non-monetary approach. PMMA working paper 2007–05, Poverty and Economic Policy Research Network.

Betti, G., & Lemmi, A. (Eds.). (2008). Advances on income inequality and concentration measures. London: Routledge.

Bibi, S., & Duclos, J. Y. (2005). Decomposing poverty changes into vertical and horizontal components. Bulletin of Economic Research, 57(2), 205–215.

Bibi, S., Castel, V., & Mejia, P. (2011). Poverty and inequality in Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania. Economic Brief 2011. Tunis: African Development Bank.

Bourguignon, F., Ferreira, F. H., & Menéndez, M. (2007). Inequality of opportunity in Brazil. Review of Income Wealth, 53(4), 585–618.

Chambers, D., & Krause, A. (2010). Is the relationship between inequality and growth affected by physical and human capital accumulation? Journal of Economic Inequality, 8(2), 153–172.

Cohen, G. A. (1989). On the currency of egalitarian justice. Ethics, 99(4), 906–944.

Dabalen, A., Narayan, A., Saavedra-Chanduvi, J., Suarez, A. H., Abras, A., & Tiwari, S. (2015). Do African children have an equal chance?: A human opportunity report for sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. World Bank.

de Barros, R. P., Ferreira, F. H. G., Molinas, J. R., & Saavedra, J. (2009). Measuring inequality of opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: World Bank–Palgrave Macmillan Publications. World Bank.

Dworkin, R. (1981). What is equality? part 2: equality of resources. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 10(4), 283–345.

Ersado, L., & Aran, M. A. (2014). Inequality of opportunity among Egyptian children. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (7026).

Ferreira, F. H., & Gignoux, J. (2011). The measurement of inequality of opportunity: Theory and an application to Latin America. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(4), 622–657.

Filmer, D. (2005). Gender and wealth disparities in schooling: Evidence from 44 countries. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(6), 351–369.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (1999). The effect of household wealth on educational attainment: Evidence from 35 countries. Population and Development Review, 25(1), 85–120.

Heckman, J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312, 1900–1902.

Huisman, J., & Smits, J. (2009). Keeping children in school: Household and district-level determinants of school dropout in 363 districts of 30 developing countries. Nijmegen Center for Economics (NiCE) Working Paper, (09-105).

Jemmali, H., & Amara, M. (2015). Assessing inequality of human opportunities: A new approach for public policy in Tunisia. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 10(2), 343–361.

Jemmali, H., & Amara, M. (2017). On measuring and decomposing inequality of opportunity among children: Evidence from Tunisia. Applied Research in Quality of Life. (In press).. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9511-1.

Kabeer, N. (2010). Can the MDGs provide a pathway to social justice? The challenges of intersecting inequalities. New York/Brighton: UN MDG Achievement Fund and Institute of Development Studies.

Ravallion, M. (1997). Can high-inequality developing countries escape absolute poverty? Economics Letters, 56(1), 51–57.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1999). The law of peoples–with the idea of public reason revisited. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. E. (1998). Equality of opportunity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. E. (2014). Economic development as opportunity equalization. The World Bank Economic Review, 28(2), 189–209.

Salehi-Isfahani, D., Hassine, N. B., & Assaad, R. (2014). Equality of opportunity in educational achievement in the Middle East and North Africa. Journal of Economic Inequality, 12(4), 489–515.

Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shorrocks, A. F. (2013). Decomposition procedures for distributional analysis: A unified framework based on the Shapley value. Journal of Economic Inequality, 11(1), 99–126.

Smits, J. (2007). Family background and context effects on educational participation in five Arab countries. Nijmegen Center for Economics (NiCE), working paper, 07-106.

Son, H. H. (2013). Inequality of human opportunities in developing Asia. Asian Development Review, 30(2), 328.

Stewart F., & Langer A. (2008). Horizontal inequalities: Explaining persistence and change. In F. Stewart (Ed.), Horizontal inequalities and conflict. Conflict, inequality and ethnicity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tansel, A. (2002). Determinants of school attainment of boys and girls in Turkey: Individual, household, and community factors. Economics of Education Review, 21(5), 455–470.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2013). Humanity divided: Confronting inequality in developing countries. New York: UNDP.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2006). Education for all global monitoring report, 2007, strong foundations: Early childhood care and education. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Population Division (UNPD). (2013). State of the World's children 2015 country statistical information [database]. United Nations Population Division.

World Bank. (2006). World development report 2006: Equity and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zhao, M., & Glewwe, P. (2010). What determines basic school attainment in developing countries? Evidence from rural China. Economics of Education Review, 29(3), 451–460.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jemmali, H. Inequality of Opportunities among Tunisian Children over Time and Space. Child Ind Res 12, 213–234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9538-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9538-3