Abstract

Inequality of opportunity (IOp) in any society is defined as that part of overall inequality which arises from factors beyond the control of an individual (circumstances) such as parental education, caste, gender, religion etc. and is thus considered unfair and is against the meritocratic values of a society. Hence, it needs to be controlled and compensated. We estimate the IOp in economic outcomes among Indian women by using the nationally representative India Human Development Survey 2011–2012. We include parental education, caste, religion and region of birth as circumstances. The overall IOp in income ranges from 18–25% and 16–21% (of total income inequality) in urban and rural areas, respectively. The corresponding figures for consumption expenditure are 16–22% and 20–23% in urban and rural areas, respectively. We also estimate the partial contributions of the circumstances to the overall IOp. We find that the parental education is the most significant contributor to IOp in urban areas, whereas, region of birth is the most significant contributor to IOp in rural areas. Fortunately, findings imply that socially and culturally imbedded factors like caste and religion which are more persistent do contribute to the IOp, but, the largest contribution is due to factors like parental education and region which can be relatively easily tackled and addressed with policy interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

“Leveling the playing field”, rather than equalizing the final results, is the objective of a “just society” (Checchi et al. 2010).

Inequality in all forms, whether economic, social or political has been a matter of serious debate and discussion both in national and international contexts. That said, a large number of studies have illustrated a clear trend of increasing inequality in the last three decades for most of the countries across the world (Morelli and Rohner 2015; OECD 2015). Such an advancing economic inequality across the globe has attracted serious intentness from the researchers as well as policymakers, thus, resulting in extensive studies been carried out in the recent decades to capture and analyse the economic inequalities mostly in the form of income or consumption expenditure inequality.

India and China have been among the fastest growing developing economies of the world and have often considered as the growth engines of the world (Callen 2007; Peterskovsky and Schüller 2010). However, the growing economic inequality in these countries has resulted in attracting significant attention from the academicians and policymakers (Jayaraj and Subramanian 2013, 2015; Lefranc et al. 2008; Luo and Zhu 2008; Milanovic 2002; Motiram and Singh 2012; Motiram and Vakulabharanam 2012; Subramanian and Jayaraj 2016; Vakulabharanam 2010; Xie and Zhou 2014).

India in the last three decades, despite showing impressive economic growth has not achieved desirable improvements in the economic and social welfare of the masses. This has given rise to widening economic inequalities (Drèze and Sen 2013). India has enormous variation in terms of caste, religion, region, sector, gender and economic classes with different groups being at differing levels of demographic and socioeconomic welfare. The varying levels of economic outcomes between different socioeconomic groups has resulted in substantial inequalities, which are rising rapidly with time (Deshpande 2011; Drèze and Sen 2013; Gang et al. 2008; Government of India 2006; Motiram and Vakulabharanam 2012; Oppenheimer 1974; Ravallion 2001; Singh et al. 2013).

Besides, the scholarship on the association between economic inequality in India and growth of Indian economy has raised concerns about the adverse effects of widening inequality for the Indian economic growth process (for example, see Weisskopf 2011). Also, in the recent times, the debate about the effect of economic inequalities on economic growth is settling towards a negative relationship between the two (for example, Berg et al. 2012; Dabla-Norris et al. 2015; Easterly 2007; Marrero and Rodríguez 2011; Ostry and Berg 2011; Ostry et al. 2014). Precisely, Berg et al. (2012) found that a 10-percentile decrease in inequality increases the length of a growth spell by 50%. Considering the large amount of economic cost which countries have to pay because of the existence of economic inequalities it has become an important issue which needs to be investigated in detail in a developing country, such as, India. Further, addressing inequality is one of the seventeen goals of the United Nations to achieve sustainable growth to transform the world into a better equitable and just society (2015).

Given the above context, it is important to note that the income inequality cannot be adequately controlled if the underlying inequality of opportunities is not addressed effectively (Sharma 2015; UN 2015). Having mentioned that, it is important to define inequality of opportunity at this juncture. Inequality of opportunity (IOp) in any society is defined as that part of overall inequality which arises from factors such as parental education, caste, gender, religion etc. (also referred as circumstances) which are beyond the control of an individual (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert 2009; Fleurbaey and Peragine 2013; Roemer 1993, 1998, 2006). Thus defined, the overall inequality in any outcome can be considered to be comprised of two components, the first being the IOp and the second being the inequality due to differential efforts or luck. Once conceptualized and defined in such a way, there is a general agreement in the existing literature that since inequality of opportunities is due to factors beyond the control of individuals, they are unfair and therefore, need to be controlled, and the individuals who are at the receiving end of inequality of opportunities need to be compensated by the society (Barros et al. 2009; Bourguignon et al. 2007; Checchi and Peragine 2010; Checchi et al. 2010; Choudhary and Singh 2017, 2018; Ferreira and Gignoux 2008; Roemer 1993, 1998, 2006).

But before one can talk about controlling IOp in any society, it is crucial to estimate it. Though the scholarship on inequality of opportunity is gaining momentum across the world, the literature on inequality of opportunity in India is rather limited. We could find only one study which has examined inequality of opportunity in economic outcomes in the Indian context. Singh (2012a) uses India Human Development Survey 2004–2005 and estimates IOp in income as well as consumption expenditure among the Indian adult males segregated by age groups and by rural urban areas. It includes father’s education, father’s occupation, caste, religion and geographic region in the list of circumstance variables.Footnote 1

It will be important to take a pause here and discuss the evolution of the notion of IOp in the literature briefly. The discussion about the role of predetermined circumstances came to the forefront in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the debate about whether one’s circumstances, such as race/ethnicity, parental education etc. (which are beyond her/his control) should affect one’s achievement, started shaping up. Thereafter a multitude of studies showed that for the same level of efforts different individuals with different circumstances attained different results (Bowles 1972; Hanoch 1967; Weiss 1970). This scholarship started a new discourse where academicians and policymakers began to investigate the contribution of circumstances in the overall accomplishment of an individual, be it related to income or cognitive abilities (see Singh 2012a for greater details). The narrative continued over time and took a formal shape in the beginning of 1990s with the studies by Roemer (1993, 1998) which conceptualized and provided an analytical framework for understanding and examining unequal opportunities. Thus, asserting that the factors determining desirable outcomes (such as income) for an individual are a result of combination of its circumstances and efforts.Footnote 2

Once the concept of IOp was formalized, empirical work on IOp started across the globe and a few early studies which shaped these estimations and brought forward the methods for estimation include (but not limited to) Bourguignon et al. (2007), Ferreira and Gignoux (2008), Barros et al. (2009), Fleurbaey and Schokkaert (2009), Checchi and Peragine (2010), Checchi et al. (2010), Suárez-Álvarez and López-Menéndez (2018a, b, c). Barros et al. (2009) and Fleurbaey and Schokkaert (2009) all the above mentioned studies have estimated IOp in economic outcomes.

The Indian socioeconomic structure is influenced by multiple caste groups, religions, regions etc. with different socioeconomic groups at different levels of socioeconomic development. Besides, with some socioeconomic groups having experienced stark discrimination and exclusion (both social and physical) or isolation (Singh et al. 2013), India is likely to suffer from substantial IOp in social as well as economic outcomes. Indeed, Singh (2012a) finds substantial inequality of opportunities in income (up to one-fourth of total income inequality) for Indian males.

Unfortunately, the above study was limited to males and we could not find (to the best of our ability) any other study which has estimated IOp in economic outcomes for Indian females. The reason for such an observation could be the following: the scholarship on IOp (across the globe; Bourguignon et al. 2007; Checchi and Peragine 2010; Checchi et al. 2010; Ferreira and Gignoux 2008 and the references therein) has singled out “parental education” as the most significant circumstance variable affecting inequality of opportunity, but the nationally representative Indian Household Surveys (for example, National Sample Surveys [NSS], India Human Development Survey [IHDS] 2004–2005, National Family Health Surveys [NFHS] etc.) do not have information on parental education for most of the adult women (Singh 2012a). The main reason for the unavailability of information on parental education (or parental occupation) for most of the women in the above surveys is the fact that the majority of the adult women (given the early marriage age in India) are either wives or daughter-in-law of the household heads for which set, the data on parental education is not collected in the above mentioned surveys (see Singh 2012a for a detailed discussion).

However, the study of IOp among women is important as various studies have argued that IOp has significant consequences for both the wellbeing of the females and the overall economic development of a society (Hoddinott and Haddad 1995; IMF 2015; Quisumbing and Maluccio 2000; Thomas 1990, 1993). The India Human Development Survey 2011–2012 is the first nationally representative survey to capture the necessary information to investigate the effect of various predetermined factors that are beyond the control of the women, on their incomes. In this paper, beyond testing the effect of the predetermined factors on the incomes of females, and calculating the overall inequality attributable to these factors, we also calculate their marginal contribution to the IOp.

Given the above, the next section describes the theoretical underpinning and empirical strategy, whereas, Sect. 3 describe the data set used in the analysis. The Sect. 4 reports our main findings, whereas, Sect. 5 discusses our main results along with listing the main conclusions and policy recommendations of this paper.

2 Theoretical Framework and Empirical Strategy

The framework and the empirical strategy has been adopted from Ferreira and Gignoux (2008, p. 6) which has been widely accepted in the inequality of opportunity literature across the globeFootnote 3 (Brunori 2016). Firstly, all the factors affecting the advantage variable [z] (which we associate with income or consumption expenditure [consumption in short]) is categorized into “circumstance” and “effort” variables [as per Roemer (1993)]. Then z is expressed as a function of circumstance variables [vector C], effort variables [vector E] and pure luck or other random factors [ε]; where effort may itself be expressed as a function of circumstances, [C], as well as other unobserved determinants [η] {that is, z = f(C, E(C, η), ε)}.

Now, let us consider a counterfactual distribution of the advantage variable \([\tilde{z}]\) (income or consumption), corresponding to F(z|C) as the distribution that arises from substituting zi with \(\tilde{z}_{i} = f[\bar{C},E(\bar{C},\eta _{i} ),\varepsilon _{i} ]\) where \(\bar{C}\) is the vector of sample mean circumstances. For generating this counterfactual distribution a specific model of z = f(C, E(C, η), ε) needs to be estimated. This counterfactual distribution keeps the within-group variation after controlling for between-group variation.

In line with Bourguignon et al. (2007) and Ferreira and Gignoux (2008), the following log-linear specification of income (or consumption) has been used:

The reduced form of the above model (1)–(2) is:

Since we are we are not interested in the causal link between circumstances and outcome, but simply in identifying inequality of opportunity we can express the above equation in its reduced form as:

Following Ferreira and Gignoux (2008, p. 11) model (3) is then estimated by OLS. The counterfactual distribution can then be expressed as:

The \(\bar{C}_{j} \hat{\varphi }_{j}\) value for the jth circumstance variable in (4) is straightforward to calculate when the variable is continuous. When the circumstance variable is categorical, then \(\bar{C}_{j} \hat{\varphi }_{j}\) is calculated as \(\sum\nolimits_{{l\varepsilon L}} {\hat{\varphi }_{j} x_{{jl}} }\), where \(\hat{\varphi }_{jl}\) in the estimated OLS coefficient of the lth level of the jth circumstance variable, xjl is the fraction of induviduals with the value of the jth circumstance variable as l, and L is the set containing all the levels of the jth circumstance variable.

The total opportunity share of income (or consumption) disparity can thus be expressed as:

In Eq. (5) the difference between the inequality in the actual distribution of outcome (total inequality) and the inequality in the counterfactual distribution of outcome (within-group inequality) gives the between-group inequality, which is expressed as a share of total inequality of income (or consumption) expressed in percentage terms.

The estimation of the individual contribution of the circumstance factors, controlling for the others can be estimated by developing alternative counterfactual distributions as below:

In Eq. (6), instead of holding all circumstance variables to be constant, as in (4), only one circumstance variable (J) is equalized across individuals, while all others are allowed to take their actual values. Hence the circumstance -specific IOp share can be obtained as:

An alternate method to the parametric method used here is a non-parametric method in which the observations are partitioned into different types based on the levels of the various circumstance variables. The inequality could then be measured using the mean outcome values of the different types. However, this is only suitable when then number of types are relatively small (Ferreira and Gignoux 2008). In our case, just by considering variables like urban, age (cohorts), caste, religion and region, there should be a total of 432 types out of which only 386 have at least one observation in the data. Moreover, the median size of the types is 42, with one-fourth of the types having no greater than 12 observations. If the parental education is also considered the number of types would increase geometrically. Thus, the parametric approach is more suitable in our case.

The method expressed in Eqs. (1)–(7) allows us to measure the ex ante IOp, which is the inequality between groups of people who face different circumstances. This is in contrast to an ex post measure which measures the inequality among people who have exerted the same degree of effort regardless of circumstances. Unlike an ex post measure, the ex ante measure does not need to use effort variable for its calculation, as it considers effort as a function of circumstances. Thus, adopting an ex ante measure allows us to account for the indirect effect of the circumstance variables (Ferreira and Gignoux 2008; Brunori 2016; Ramos and Van de Gaer 2016).

Before describing the data, we would like to mention that (to capture how inequality of opportunity may vary across age based groups) we have partitioned the sample into different age based groups (cohorts): 15–28 years, 29–36 years, 37–44 years and 45 years and above (age quartiles), respectively. There have been similar studies which have used age as a cohort and our results can be easily compared with the results of those studies such as Singh (2012a) for inequality of opportunity for Indian males. For each cohort, the examination has been conducted separately for urban and rural areas. The separate analysis for rural and urban areas is informed by the fact the sources of income and expenditure, labor market conditions, as well as job environment are very different in these areas (Singh 2012a). For both types of areas, examinations based on income and consumption expenditure have been performed. The above mentioned set of examinations have been performed because such an exercise will give a complete picture (encompassing two important indicators of welfare) on one hand and coherence in estimates of shares of opportunity in income and consumption inequality will signal about the robustness of the estimation on the other.

We have chosen Mean-log deviation (MLD) as the measure of inequality in the present paper. This choice is motivated by the fact that, it is the only inequality measure which has been consistent with the six properties of (1) anonymity or symmetry; (2) population replication or replication invariance; (3) mean independence or scale invariance; (4) Pigou-Dalton principle of transfers; (5) additive subgroup decomposability; and (6) path independence.Footnote 4

We now present the details of data and the circumstance as well as effort variables.

3 Data and Variables Description

The data for the present study is taken from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) 2011–2012. The IHDS is a nationally representative survey of 42,152 households across India. The survey covers all states and union territories of India (except the Andaman/Nicobar and Lakshadweep islands). The IHDS was conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), New Delhi in collaboration with the University of Maryland (Desai et al. 2015). It included modules on health, education, employment, economic status, marriage, fertility, gender relations, and social capital (Desai et al. 2015). The survey questionnaires were translated into thirteen Indian languages and local interviewers were used to conduct the survey.

One ever-married woman aged 15 years and above from every household (totally 42,152 households), was specially interviewed to understand the economic, social and demographic welfare (including health, education, family planning, marriage, gender relations etc.) of women in India. Detailed background information (including parental education) was collected for this set of women, and these women form the sample for the analysis conducted in this paper. Appropriate sampling weights as provided in the survey have been used to derive the estimates at national and regional levels (Desai et al. 2015).

For analyzing IOp, the variables of advantage (term used by Roemer (1998) for economic outcomes) used in the estimation are the logarithm of income (annual household per capita) and consumption (expenditures) (monthly household per capita). To capture circumstances, we include parental education (father’s or mother’s education whichever is higher) in terms of years of schooling, caste, religion and geographical region of birth. Due to the lack of direct information on region of birth, we have taken region of residence as a proxy for region of birth.Footnote 5

Given the general agreement among demographers about the importance of parental education as a suitable variable for capturing family influence (Davis-Kean 2005; Eccles and Davis-Kean 2005). Besides, earlier studies (Bourguignon et al. 2007; Checchi and Peragine 2010; Ferreira and Gignoux 2008; Singh 2012a) narrow down on parental education as the most influential circumstance variable as far as IOp is concerned; we have chosen parental education as one of the circumstance variables. Talking about parental education, we found a high degree of correlation between father’s and mother’s education, so we constructed parental education as a maximum of the father’s or mother’s education (that is, father’s or mother’s education whichever is higher) in terms of years of schooling.

Caste as a circumstance variable has been divided into three categories; “Other Castes (OC)” [also “General” or “Upper Castes”, “Other Backward Castes” (OBC) and “Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes” (SC/ST) with “OC” being taken as the reference category (in the regressions).Footnote 6 Individuals belonging to SC/ST community have experienced substantial exclusion (physical and social) and discrimination since ancient times and lag behind the non-Scheduled groups in various indicators of demographic, economic and social welfare (Deshpande 2011; Singh et al. 2013). Similarly, religion has also been grouped into three categories; “Hindu” (majority in India), “Muslim” and “Others” with “Hindu” as the reference category. Muslims in India lag their Hindu counterparts to a large extent in various outcomes including education, income and employment (Government of India 2006).

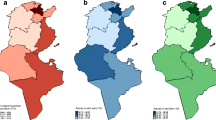

The different regions of India are at various thresholds of demographic, economic and social development; most of the states in the central and eastern regions of India are lagging the other states as far as demographic, economic and social indicators are concerned (Bhat and Zavier 1999; Pathak and Singh 2009; Singh 2011). To capture the influence of geographical region of birth (proxied by geographical region of residence) on the income and consumption, our estimation also includes geographical region of birth (proxied by geographical region of residence) as one of the circumstance variables.Footnote 7

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and Results of Regressions

Tables 1 and 2 present the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis. It can be seen from the Table 1 that the mean income, as well as mean consumption (expenditure) are much higher for the urban areas (mean income 39,302.31; mean consumption 33,409.19) than that of the rural areas (mean income 22,247.33; mean consumption 21,888.26). The mean parental education is also reasonably lower for the rural areas (2.82 years) compared to that of the urban areas (5.07 years). This impresses upon the great rural–urban divide in India as far as demographic, economic and social outcomes are concerned. The mean income, as well as consumption, seems to increase with age. This probably reflects the effect of experience on earnings. Also, parental education shows a decrease as we move from the younger to older generations, 3.7–1.6 years for rural areas and 5.8–3.9 years in urban areas. This trend is observed in all areas and is in line with the fact that levels of education have gradually improved in India since the Indian independence in 1947. However, the sharp rural urban divide certainly impresses upon the need for dedicated policies by government to improve the access to school and quality of education in rural areas to weaken this gap between rural and urban areas as far as education is concerned.

From Table 1, we also find that the mean income, as well as consumption of SC/STs (Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes), is substantially lower than that of the OCs (the upper/general castes). This observation is in line with the socioeconomic landscape of India. In fact, the trend is that the income, as well as consumption of OCs (mean income 31,018.76; mean consumption 27,693.54) is higher than the OBCs (mean income 20,671.78; mean consumption 22,051.76) and the income, as well as consumption of OBCs is higher than that of SC/STs (mean income 17,439.23; mean consumption 17,268.48) in all the cohorts in rural areas. Whereas, in urban areas the income as well as consumption of OCs (mean income 49,637.77; mean consumption 39,311.25) is substantially higher than both the OBCs (mean income 33,129.26; mean consumption 30,962.58) as well as SC/STs(mean income 33,327.23; mean consumption 27,985.93) but there is no clear cut trend between the OBCs and SC/STs. Similarly, the mean income as well as consumption of Muslims is substantially lower than that of Hindus, as well as the populace practicing other religions in both rural and urban areas. Moreover, the mean income and consumption in central and eastern regions which comprise of the socioeconomically more impoverished states of India is substantially lower than that of the other regions. This observation is true for all the age cohorts and both rural as well as urban areas.

Table 2 presents the share of total women within each category of each circumstance and also share of women within each category of circumstances with an income/consumption below the overall median for each cohort. Trends of median are very similar to that of means for income as well as consumption expenditure, median (both income and consumption expenditure) increases with age cohorts and is significantly more in urban areas than that of rural areas. Another interesting thing to note from Table 2 is for Other’s and OBC’s caste category share of women below median (both income and consumption) is slightly higher in urban areas as that of rural areas. However, the case is opposite for the SC/STs women. That indicates caste based discrimination especially for SC/STs is much higher in rural areas than urban areas. On the other hand, among Muslim women, their proportion below median income is higher (70%) in urban areas than that of rural (57%) areas. That said, government here should intervene and take some measures to empower women specifically Muslim women in urban areas to eventually increase their proportion in mainstream jobs. Also, likewise the trends observed from Table 1 proportion of females below median (earnings and Consumption) is significantly high in central and eastern region for both rural as well as urban areas.

Tables 3 (rural) and 4 (urban) present OLS estimates of Eq. (3) (for measuring the overall opportunity’s share of income and consumption). Furthermore, Tables 3 and 4 show that the parental education plays a positive and highly significant role in determining the income as well as consumption expenditure of the Indian women (all cohorts; both rural and urban areas). Also, as expected, the income, as well as consumption expenditure of women belonging to OBCs and SC/STs is significantly lower than that of the women belonging to OCs in all the cohorts in both rural as well as urban areas. Similarly, Muslim women have a substantially lower income (and consumption expenditure) across all age cohorts both in rural as well as urban areas. Again, in line with the expectations, women belonging to the regions of central and east which include the most (economically, demographically and socially) poor states (Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal) of India have considerably lower income (as well as consumption expenditure) across all cohorts both in rural and urban areas compared to that of women belonging to the advanced regions of North, South and West.

4.2 Estimates of Inequality of Opportunities (IOp)

Using the estimates of the coefficients presented in Tables 3 and 4, counterfactual distributions corresponding to Eq. (4) have been generated for rural and urban areas, respectively. Table 5 reports the Mean Log Deviation (MLD) coefficients for factual and counterfactual income (and consumption) distributions for all the age-groups in urban and rural areas. It also reports the corresponding estimates of overall IOp. In rural areas (Table 5A), the overall opportunity’s share in total income inequality [obtained using Eq. (5)] varies from 21 to 16% across the age groups, the simple average across age groups being 19%. The corresponding estimates for consumption expenditure inequality are 21–24% (22% being the simple average).

In urban areas (Table 5B), the overall opportunity’s share in total income inequality varies from 25 to 18% across different age groups, the simple average across age groups or cohorts being 20%. The opportunity’s share is highest for the 29–36 years. age cohort. The respective estimates for consumption expenditure inequality stand at 22–22% with a simple average across cohorts being 19%. One important point worth noting is that in rural areas the IOp in consumption expenditure is slightly higher than the IOp in income whereas, it is the other way round in urban areas.

Table 6 reports the MLD estimates for actual income (and consumption expenditure) and counterfactual income (and consumption expenditure), arrived at by equalizing each individual circumstance variable in turn, while controlling for all others [Eq. (6)]. Each circumstance specific opportunity’s share of overall inequality [obtained using Eq. (7)] has also been presented. In rural areas (Table 6A), it is the region of birth which seems to have the highest opportunity’s share in income inequality (Panel 1, column 8). The opportunity’s share in overall income inequality due to the region of birth ranges from 8 to 13% across the cohorts. The second highest opportunity share in income inequality results from parental education (column 10) (about 4–7%) followed by caste (column 4) and is about 3–5%. The case of consumption expenditure is slightly different where it is the caste which contributes slightly more than the parental education to the overall inequality (Panel 2).

In urban areas (Table 6B), the estimates of opportunity’s share of overall observed income and consumption expenditure inequality due to parental education is the most dominating one. If the case of income inequality (Panel 1) is observed then the opportunity share due to parental education varies from 11 to 17% across the age cohorts, the highest being in the age group 29–36 years. After, parental education there is no clear cut pattern with different factors contributing differently to different cohorts. In the case of consumption expenditure, the opportunity share due to parental education varies from 8 to 14% across the age groups, the highest again being in the age group 29–36 years. Also, caste and region of birth make almost similar but substantial contribution to the overall inequality.

5 Conclusions and Discussion

Our study presents the estimates of overall inequality of opportunity in earnings as well as consumption expenditure for both rural as well as urban women in India. The study also gives insights on how several circumstances such as parental education, caste, religion and region of birth affect desirable outcomes, such as income and consumption expenditure of an Indian woman. In view of the fact that this study addresses an important concern which has so far not been addressed for Indian women, it is interesting to compare it with the case of Indian men (Singh 2012a) and with that of studies from different countries across the globe.

Comparisons based on studies using similar approach suggests that the total IOp in income as well as consumption expenditure for Indian women is lower as compared to the Latin American countries such as Colombia, Peru, Panama, Ecuador, Guatemala and Brazil (Ferreira and Gignoux 2008, 2011). Whereas, total IOp in income as well as consumption expenditure found from current study is higher than that of all of the European countries covered in Checchi et al. (2010).Footnote 8 Also, the inequality of opportunity estimates for women from our analysis are similar to that of the men in India presented in Singh (2012a). Further, the trends presented in this paper, like parental education being the highest contributor to the overall IOp in urban areas whereas region of the birth is the highest contributor to the overall IOp in rural areas is also in line with Singh (2012a).

We found that the parental education is not the highest contributor to Inequality of opportunities in rural areas which might be due to the fact that the lack of infrastructure in rural areas curtails the options available to parents related to schooling decisions about their children. For example, if parents decide about the nature of schooling which may later affect their children’s income and in turn consumption, then due to lack of options in availability of schools, even highly educated parents will have no choice but to send their children to the same (and only) school (probably in the same village) where parents with relatively lower education are sending their children. Hence, higher parental education might not result into better education for their children which in turn will not convert into superior income (a point also noted in Singh 2012a).

Our findings related to caste and religion being important factors contributing to the difference between incomes of Indian women is in line with the existing scholarship on the subject (Deshpande 2011; Government of India 2006; Gang et al. 2008). The above literature has concluded that a major part of the disparity in outcomes (educational or income) can be substantiated by the disparity in caste and religious backgrounds of the populace. Therefore, our results become important if observed through the lens of affirmative action in favor of the individuals belonging to lower caste categories or the Muslim community.

We would also like to mention here that the overall estimates of IOp presented in this paper are lower bound estimates due to the fact that it is not possible to neglect the existence of other unobserved circumstance variables. Including additional circumstance variables (in the estimated equations) which are independent (or orthogonal) to the circumstance variables included in the present analysis will reduce the variance of the random or luck factors but will increase the variance of the circumstance variables thus taking the IOp share of total inequality upwards (Barros et al. 2009, p. 127).

Although the use of a standard and well accepted framework as well as similarity in the IOp estimates in income and consumption expenditure can be seen as suggesting that the estimates presented in this paper are quite robust, some caution still need to be exercised while interpreting our findings. For example, the variation of inequality of opportunity estimates for various age based cohorts should not be construed as variations over time. This is due to the fact that they are estimated at the same time point, and it is impossible to separate the period/age and cohort effects (Bourguignon et al. 2007, p. 613). So the results are for the specific cohorts during 2011–2012. That said, this is a limitation of any study (such as, Bourguignon et al. 2007; Singh 2012a etc.) which examines inequality of opportunity in income (or consumption) among individuals belonging to different age based cohorts at a given point of time.

One positive outcome from our findings worth noting is that the variation in circumstantial factors like parental education and region which are the most significant factors contributing to the overall inequality of opportunities are the factors which can be relatively easily tackled and addressed with policy interventions than the socially and culturally embedded and rigid factors like caste and religion which are more persistent and would have been harder to address since Indian independence. However, policymakers also need to take some measures to encourage Muslim women to participate in mainstream jobs. The agenda for a government aiming to reduce the inequality of opportunities in India should be to direct more attention towards removing educational and regional disparities, while still focusing on promoting caste and religion based equality.

Last but not the least, policymakers need to ensure equal opportunities and reduce disparities in economic as well as social outcomes if the focus is on eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices. In this regard, lessons can be drawn from some recent statistics which have shown that it is wholly possible. For example, it has been found that from 2007 to 2012, the growth in mean income of the poorest families in more than fifty countries, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean as well as Asia was higher than the growth in national averages, reducing the earnings disparity in those countries (2015).

Notes

See Singh (2012a) for a more elaborate literature review on the evolution of the concept of IOp.

Since, the geographical regions of residence are large regions consisting of multiple states, the migration between regions is substantially low. In the urban as well as rural areas less than 10% of the total individuals have migrated from another state. Though, it is difficult to say anything about between-region migration, it can always be argued that between-region migration will be lower than the above estimate because every region consists of multiple states and therefore a lot of between-state migration cases will fall into within-region migration category. We could not include parental occupational status; because the information on parental occupation is not available for the women covered in the analysis.

‘Others’ caste is referred to ‘general’ class or the uplifted castes in the Indian system. SC/STs are the historically socially and economically disadvantaged caste groups, who have suffered from severe discrimination as well as social and physical exclusion on the hands of ‘Others’. The condition of OBCs have been better than the SC/STs but worse than the ‘Others’.

Region is categorized into six categories, namely, North (Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, Uttaranchal, Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan), Central (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh), East (Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal and Orissa), North-east (Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura, Nagaland and Sikkim), West (Maharashtra, Goa and Gujarat), and South (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry). Northern region has been taken as the reference category in the estimation. Kindly see Singh (2012a) for a detailed discussion on the categorization of states into regions.

Checchi et al. (2010) have estimated IOp in earnings for 25 European countries including Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom. Here the comparison has been made in terms of the absolute values (level) of IOp and not in terms of IOp as a share of overall inequality.

References

Asadullah, M. N., & Yalonetzky, G. (2012). Inequality of educational opportunity in India: Changes over time and across states. World Development, 40(6), 1151–1163.

Barros, R. P., Ferreira, F. H. G., Vega, J. R. M., & Chanduvi, J. S. (2009). Measuring inequality of opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: Palgrave Macmillan and The World Bank.

Berg, A., Ostry, J. D., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2012). What makes growth sustained? Journal of Development Economics, 98(2), 149–166.

Bhat, P. M., & Zavier, F. (1999). Findings of national family health survey: Regional analysis. Economic and Political Weekly, 3008–3032.

Bourguignon, F., Ferreira Francisco, H. G., & Menéndez, M. (2007). Inequality of opportunity in Brazil. Review of Income and Wealth, 53(4), 585–618.

Bowles, S. (1972). Schooling and inequality from generation to generation. Journal of Political Economy, 80(3), S219–S251.

Brunori, P (2016). How to measure inequality of opportunity: A hands-on guide? Life Course Centre working paper series no 2016-04. Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland.

Callen, T. (2007). PPP versus the market: Which weight matters? Finance and Development, 44(1), 50.

Checchi, D., & Peragine, V. (2010). Inequality of opportunity in Italy. Journal of Economic Inequality, 8(4), 429–450.

Checchi, D., V. Peragine, & Serlenga, L. (2010). Fair and unfair income inequalities in Europe. ECINEQ working paper 174, Society for Study of Economic Inequality.

Choudhary, A., & Singh, A. (2017). Are daughters like mothers: Evidence on intergenerational educational mobility among young females in India. Social Indicators Research, 133(2), 601–621.

Choudhary, A., & Singh, A. (2018). Examination of intergenerational occupational mobility among Indian women. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(7), 1071–1091.

Dabla-Norris, M. E., Kochhar, M. K., Suphaphiphat, M. N., Ricka, M. F., & Tsounta, E. (2015). Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294–304.

Desai, S., Dubey, A. &Vanneman, R. (2015). India human development survey-II (IHDS-II), 2011–12. ICPSR36151-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Deshpande, A. (2011). The grammar of caste. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Drèze, J., & Sen, A. (2013). An uncertain glory: India and its contradictions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Easterly, W. (2007). Inequality does cause underdevelopment: Insights from a new instrument. Journal of Development Economics, 84(2), 755–776.

Eccles, J. S., & Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). Influences of parents' education on their children's educational attainments: The role of parent and child perceptions. London review of education, 3(3), 191–204.

Ferreira, F., & Gignoux, J. (2008). The measurement of inequality of opportunity: Theory and an application to Latin America. World Bank Policy research working paper no. 4659. New York: World Bank.

Ferreira, F., & Gignoux, J. (2011). The measurement of inequality of opportunity: Theory and an application to Latin America. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(4), 622–657.

Fleurbaey, M., & Peragine, V. (2013). Ex ante versus ex post equality of opportunity. Economica, 80, 118–130.

Fleurbaey, M., & Schokkaert, E. (2009). Unfair inequalities in health and health care. Journal of Health Economics, 28(1), 73–90.

Foster, J. E., & Shneyerov, A. A. (1999). A general class of additively decomposable inequality measures. Economic Theory, 14(1), 89–111.

Foster, J. E., & Shneyerov, A. A. (2000). Path independent inequality measures. Journal of Economic Theory, 91(2), 199–222.

Gang, I. N., Sen, K., & Yun, M. S. (2008). Poverty in rural India: Caste and tribe. Review of Income and Wealth, 54(1), 50–70.

Government of India. (2006). Social economic and educational status of muslim community in India. New Delhi: Government of India.

Hanoch, G. (1967). An economic analysis of earnings and schooling. Journal of human Resources, 2(3), 310–329.

Hoddinott, J., & Haddad, L. (1995). Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57(1), 77–96.

Jayaraj, D., & Subramanian, S. (2013). On the inter-group inclusiveness of India’s consumption expenditure growth. Economic and Political Weekly, 48(10), 65–70.

Jayaraj, D., & Subramanian, S. (2015). Growth and inequality in the distribution of India’s consumption expenditure 1983 to 2009–2010. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(32), 39–47.

Lefranc, A., Pistolesi, N., & Trannoy, A. (2008). Inequality of opportunities versus inequality of outcomes: Are Western societies all alike? Review of Income and Wealth, 54(4), 513–546.

Luo, X., & Zhu, N. (2008). Rising income inequality in China: A race to the top. Policy Research working paper no. 4700. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Marrero, G., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2011). Inequality of opportunity in the United States: Trends and decomposition. In J. Bishop (Ed.), Inequality of opportunity: Theory and measurement (research on economic inequality) (Vol. 19, pp. 217–246). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Milanovic, B. (2002). True world income distribution, 1988 and 1993: First calculation based on household surveys alone. The Economic Journal, 112(476), 51–92.

Morelli, M., & Rohner, D. (2015). Resource concentration and civil wars. Journal of Development Economics, 117(3), 32–47.

Motiram, S., & Singh, A. (2012). How close does the apple fall to the tree? Some estimates on intergenerational occupational mobility for India. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(40), 56–65.

Motiram, S., & Vakulabharanam, V. (2012). Indian inequality: patterns and changes, 1993 – 2010. India development report. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

OECD. (2015). OECD education at a glance. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/edu/education-at-a-glance-2015.htm.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1974). The life-cycle squeeze: The interaction of men’s occupational and family life cycles. Demography, 11(2), 227–245.

Ostry, J. D., & Berg, A. (2011). Inequality and unsustainable growth; two sides of the same coin? (No. 11/08). Washington DC: International Monetary Fund.

Ostry, M. J. D., Berg, M. A., & Tsangarides, M. C. G. (2014). Redistribution, inequality, and growth. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund.

Pathak, P. K., & Singh, A. (2009). Geographical variation in poverty and child malnutrition in India. In Population, poverty and health: Analytical approaches (pp. 183–206). New Delhi: Hindustan Publishing Corporation.

Peterskovsky, L., & Schüller, M. (2010). China and India—The new growth engines of the global economy? GIGA focus international edition English, (04). Chennai: GIDA Institute of Asian Studies.

Quisumbing, A. R., & Maluccio, J. A. (2000). Intrahousehold allocation and gender relations: New empirical evidence from four developing countries. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Ramos, X., & Van de Gaer, D. (2016). Approaches to inequality of opportunity: Principles, measures and evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys, 30, 855–883.

Ravallion, M. (2001). Growth, inequality and poverty: Looking beyond averages. World Development, 29(11), 1803–1815.

Roemer, J. E. (1993). A pragmatic theory of responsibility for the egalitarian planner. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 22(2), 146–166.

Roemer, J. E. (1998). Equality of opportunity (No. 331.2/R62e). Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. E. (2006). Economic development as opportunity equalization. Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper, No 1583, Yale University.

Sharma, S. (2015). Caste-based crimes and economic status: Evidence from India. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(1), 204–226.

Shorrocks, A. F. (1980). The class of additively decomposable inequality measures. Econometrica, 48(3), 613.

Shorrocks, A. F., & Wan, G. (2005). Spatial decomposition of inequality. Journal of Economic Geography, 5(1), 59–81.

Singh, A. (2011). Inequality of opportunity in Indian children: The case of immunization and nutrition. Population Research and Policy Review, 30(6), 861–883.

Singh, A. (2012a). Inequality of opportunity in earnings and consumption expenditure: The case of Indian men. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(1), 79–106.

Singh, A. (2012b). Inequality of opportunity in access to primary education among Indian children. Population Review, 51(1), 50–68.

Singh, A., Das, U., & Agrawal, T. (2013). How inclusive has regular employment been in India? A dynamic view. The European Journal of Development Research, 25(3), 486–494.

Singh, A., Singh, A., Pallikadavath, S., & Ram, F. (2014). Gender differentials in inequality of educational opportunities: New evidence from an Indian youth study. The European Journal of Development Research, 26(5), 707–724.

Suárez Álvarez, A., & López Menéndez, A. J. (2018a). Assessing changes over time in inequality of opportunity: The case of Spain. Social Indicators Research, 139(3), 989–1014.

Suárez Álvarez, A., & López Menéndez, A. J. (2018b). Income inequality and inequality of opportunity in Europe. Are they on the rise. In J. Bishop, & J. Gabriel (Eds.), Inequality, taxation and intergenerational transmission, Vol: 26 (Research on Economic Inequality Series).

Suárez Álvarez, A., & López Menéndez, A. J. (2018c). Inequality of opportunity in developing countries: Does the income aggregate matter? LIS WP 2018-739. Available in http://www.lisdatacenter.org/.

Subramanian, S., & Jayaraj, D. (2016). The quintile income statistic, money-metric poverty, and disequalising growth in India: 1983 to 2011–12. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(5), 73–79.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 635–664.

Thomas, D. (1993). The distribution of income and expenditure within the household. Annalesd’ Economie et de Statistique, 29(1), 109–135.

United Nations. (2015). 17 goals to transform our world: Sustainable development goals. Retrieve at http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

Vakulabharanam, V. (2010). Does class matter? Class structure and worsening inequality in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 45(29), 67–76.

Weiss, R. D. (1970). The effect of education on the earnings of blacks and whites. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 150–159.

Weisskopf, T. E. (2011). Why worry about inequality in the booming Indian economy? Economic and Political Weekly, 46(47), 41–51.

Xie, Y., & Zhou, X. (2014). Income inequality in today’s China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(19), 6928–6933.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ashish Dangi and Ram Kumar for providing suggestions and comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choudhary, A., Muthukkumaran, G.T. & Singh, A. Inequality of Opportunity in Indian Women. Soc Indic Res 145, 389–413 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02097-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02097-w