Abstract

Self-compassion promotes well-being and positive outcomes when encountering negative life events. The current study investigates the relation between self-compassion and romantic jealousy in adults’ romantic relationships, and the possible mediation effects of anger rumination and willingness to forgive on this relation. Romantic jealousy was conceptualized as reactive, which is a more emotional type, and as anxious, which is a more cognitive type. We hypothesized a negative association between self-compassion and romantic jealousy. In the present study 185 German adults (64 men, 121 women) participated, aged between 18 and 56 years (M = 32.28, SD = 12.14) who were in a romantic relationship. The participants completed the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS, Neff in Self and Identity, 2, 223–250, 2003a), a reactive and anxious jealousy scale (Buunk in Personality and Individual Differences, 23(6), 997–1006, 1997), a willingness to forgive scale (TRIM, McCullough et al. 2000) and the Anger Rumination Scale (ARS, Sukhodolsky et al. in Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 689–700, 2001). Supporting our hypotheses, hierarchical regression analyses showed that self-compassion predicts reactive and anxious jealousy when controlling for age and gender, suggesting that high self-compassionate people are less prone to experience romantic jealousy. Multiple parallel mediation analyses revealed that the effects on reactive jealousy were partially mediated by willingness to forgive, while no significant mediation was found for the effects on anxious jealousy. Additionally, we report the results of exploratory analyses testing the associations of the self-compassion subscales with romantic jealousy. We discuss theoretical conclusions for jealousy and self-compassion research and practical implications for couple’s therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Jealousy has been rated as one of the most frequent problems facing couples in romantic relationships (e.g., Miller et al. 2014; Zusman and Knox 1998), and some of its possible consequences, such as separation or divorce, have for a long time been judged among the most stressful life events (e.g., Holmes & Rahe, 1967). From an evolutionary perspective, romantic jealousy evolved to alert individuals to possible relationship threats and prompt them to take action to prevent a partner from abandoning the relationship (e.g., Buss 1994). Romantic jealousy therefore increases individuals’ and their offspring’s chances of survival (e.g., Fisher 2000). Individuals’ interpretation and appraisal of a relationship threat have also been considered (e.g., Social-Cognitive Theory of Jealousy; Harris 2003), and it has been found that the likelihood of experiencing romantic jealousy increases when relationship rewards are perceived as threatened and when some aspects of the individual’s self-concept are perceived as being challenged by a rival. By positing these individual appraisal processes, the social.cognitive framework also accounts for individual differences in jealousy. Self-compassion is an emotional regulation strategy (Neff 2003a) that can help people to turn negative self-affect into positive self-affect and should therefore have a strong influence on the appraisal of a possible betrayal in the relationship. In this respect, self-compassion has already proven to be associated with healthier outcomes in romantic relationships (e.g., relationship satisfaction; Neff and Beretvas 2012). However, self-compassion’s role in predicting jealousy reactions has not yet been considered. In an effort to narrow this gap in the literature, we studied self-compassion’s effect on reactive and anxious jealousy and examined possible pathways explaining this association by including willingness to forgive and anger rumination as mediators.

Romantic Jealousy

Romantic jealousy is defined as a response to a loss of or an experienced threat to a significant, mostly sexual, relationship due to an imagined or actual emotional or sexual involvement of the partner with someone else (Bringle and Buunk 1985). Consistent with the different aspects of this definition, research has distinguished between different types of romantic jealousy (Buunk 1997; Mathes 1991; Pfeiffer and Wong 1989). One of the most prominent approaches in recent research is the multidimensional concept of Buunk (1997) who proposed three qualitatively different types of jealousy: reactive, preventive, and anxious. Reactive jealousy (emotional component) refers to the degree that people experience strong negative emotions when their partner engages in unfaithful behaviors, for example, kissing or flirting with a third person. Preventive jealousy (behavioral component) describes the effort people invest to prevent their partner from getting involved with people who are potential rivals. Finally, anxious jealousy (cognitive component) refers to a process in which the individual worry about and cognitively generates images about a partner’s cheating behavior, which is connected with experiencing feelings of worry and suspicion.

Important to Buunk’s typology is that jealousy is not only activated by an actual relationship threat (reactive type) but also when a potential rival is absent (preventive and anxious type; Buunk and Dijkstra 2006). Moreover, these different jealousy types constitute a continuum ranging from healthy and rational behaviors related to reactive jealousy at one end and unhealthy and problematic behaviors related to preventive and anxious jealousy at the other end. Preventive jealousy is also described as a consequence or weakened form of anxious jealousy. A two-factor model of jealousy consisting of the reactive and anxious types has been suggested in recent research (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007; see also Buunk 1997; Buunk and Dijkstra 2004). Therefore, we focused only on reactive (emotional) and anxious jealousy (cognitive) in the present study to obtain distinct measurements for emotional reactions to a situational threat and measurements of processes relying more on personal dispositions and cognitions such as insecurity and anxious rumination. These two jealousy types are especially important when assessing effects on relationship outcomes. Reactive jealousy has consistently shown adaptive effects on relationship adjustment, satisfaction, and quality, whereas anxious jealousy has been associated with strong negative relationship outcomes (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007). Effects of preventive jealousy have been inconsistent, and significant effects have had small effect sizes (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007).

The evoking of jealousy has been described within the Social-Cognitive Theory of Jealousy (Harris 2003). In line with most theories of emotions, here, cognitive appraisals are a core component in eliciting emotional reactions. They guide the interpretation and appraisal of a variety of threats. That is, the actual experience of romantic jealousy results from a person’s perception that another person or a rival (who may even be imaginary) threatens the existence or quality of a rewarding relationship and/or challenges some aspects of the person’s self-representation and self-concept. Harris (2003) incorporated Lazarus’ cognitive theory of emotions (Lazarus 1991) as a feasible model to describe associations between appraisal processes and jealous reactions: She suggests that the primary appraisal (an assessment that an event has positive, negative or no impact on one’s goals or the self) may result from a positive interaction between one’s partner and a potential rival, which can trigger the perception of a threat. Consequently, further appraisals determine the importance of that interaction for one’s relationship and the self and finally result in jealous reactions. Appraisals can vary across individuals because different aspects of the self can be threatened by infidelity. The social cognitive theory can therefore also account for individual differences in experiencing jealousy.

Self-Compassion

When people are confronted with uncontrollable life events, personal inadequacies, or failures, they differ in their responses to these circumstances. Some people tend to react to difficult circumstances in a self-critical way, whereas others tend to treat themselves with warmth and comprehension (Neff 2003b). The latter, emotionally positive, self-attitude was conceptualized by Neff (2003a) as self-compassion. According to Neff (2003a, b, 2009), self-compassion consists of three bipolar components (constituting its six subscales): self-kindness versus self-judgement, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification. (a) Self-kindness enables people to handle difficult circumstances in life by being caring and kind towards themselves rather than being self-critical (self-judgment). (b) Common humanity refers to an understanding that suffering, failure, and inadequacies are part of human life rather than personal misery. On the other hand, experiencing suffering as purely personal might lead to feelings of isolation and separation (isolation). (c) Mindfulness refers to the ability to observe one’s feelings about difficult situations in life with an understanding, non-judgemental attitude rather than exaggerating or suppressing them (over-identification). This empowers people to hold their feelings in balanced awareness (Neff 2003b, 2009). The three bipolar components of self-compassion have been shown to be highly intercorrelated. Thus, they can be conceived of as a single overarching factor named self-compassion (Neff 2003a, 2009).

Neff (2003a) argued that self-compassion can be viewed as an emotion regulation strategy transforming negative self-affect (i.e., feeling bad about failure) into positive self-affect (i.e., feeling kindness towards oneself), and therefore should be related to numerous psychological benefits. An abundance of research has demonstrated adaptive effects on individual outcomes. When confronted with stressors, such as academic failure or serious illness, self-compassion buffers people against the emotional impact and fosters better adjustment (Brion et al. 2014; Neff et al. 2005). Self-compassion also affects personal dispositions and cognitions. For example, it is positively associated with optimism and happiness (Neff et al. 2007b), with life satisfaction (Neff 2011) and negatively related to depression and anxiety (Neff 2003b; Neff et al. 2007b).

Within the context of interpersonal relationships, self-compassion is predominately associated with adaptive outcomes. For example, Yarnell and Neff (2012) found that for various types of relationships self-compassion is positively related to a tendency to resolve interpersonal conflict through compromise, and to higher levels of relational well-being. For particular types of relationships, such as romantic relationships, research has also found that self-compassion is connected with healthier relationship behaviors such as being more caring and less detached with partners (Neff and Beretvas 2012). Romantic relationship partners of self-compassionate people have also reported higher relationship satisfaction (Neff and Beretvas 2012). To better understand the role of self-compassion in the context of romantic relationships, research on its impact on particular relational conflict situations such as romantic jealousy might be helpful.

Furthermore, studying the associations of the self-compassion subscales with interpersonal outcomes might be helpful in gaining more fine-grained information about the role of self-compassion in these outcomes. Neff (2016) states that “each pair of opposing components focus on a different dimension of self-to-self relating…” (p. 791); the self-kindness vs. self-judgment bipolar component refers to individuals’ emotional responses, the common humanity vs. isolation bipolar component refers to the cognitive understanding of people, and the mindfulness vs. over-identification bipolar component refers to the amount of attention individuals pay to their suffering. Recent studies on predicting anger rumination (Fresnics and Borders 2017) have already demonstrated a particular pattern of associations with the self-compassion subscales. Here, the subscale over-identification was the driving force, while the remaining subscales had no unique predictive power. Hence, we included the subscale analysis in an exploratory analysis to determine in more detail which specific subscales are responsible for any associations of self-compassion with romantic jealousy.

The Self-Compassion – Romantic Jealousy Link and Possible Mediators

There are good reasons to hypothesize a negative association between self-compassion (as measured by the total score) and reactive jealousy. Individuals high in self-compassion have been found to experience less emotional turmoil when resolving conflicts with their romantic partner (Kelly et al. 2009; Yarnell and Neff 2012). Reactive jealousy involves a strong emotional reaction to a conflict in the relationship (a perceived betrayal), so it should also be reduced in individuals with greater self-compassion. We also hypothesize that the opposing subscales mindfulness and over-identification are most important for this association, as they both measure the way in which people handle emotions in stressful situations (Neff 2016). However, this hypothesis is somewhat more exploratory, as there is to our knowledge no existing research on the role of the self-compassion subscales in romantic relationships. Previous research suggests that there will also be a negative relationship between self-compassion (total score) and anxious jealousy. Anxiety, along with related traits such as self-criticism and depression, has already been found to be negatively related to self-compassion (Neff 2003b, 2009). We hypothesize that among the self-compassion subscales the opposing components self-kindness vs. self-judgment and common humanity vs. isolation are the most important for this association, since these components shape emotional, cognitive, and judgmental reactions to critical events that may contribute to insecurity and rumination (Neff 2016). Again, our hypotheses concerning the subscales are necessarily exploratory.

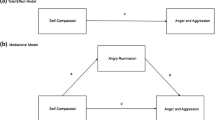

Little research attention has investigated the mechanisms by which self-compassion affects interpersonal outcomes. Understanding these mechanisms might not only extend our understanding of self-compassion but could also contribute to the development of jealousy interventions. In the current study, we propose that willingness to forgive and anger rumination might be relevant mediators of self-compassion effects (total score) on anxious and reactive jealousy. (Fig. 1 displays our Parallel Mediational Models.) Jealousy intervention studies (e.g., DiBlasio 2000) and studies on interpersonal relationships (e.g., Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007, Murphy et al. 2015) have already suggested that these processes seem to be relevant in shaping the experience of romantic jealousy. Further, rumination and willingness to forgive have been shown to be robustly negatively correlated with each other in a variety of different situations involving interpersonal transgressions. This correlation persists over time in cross-lagged study designs, and even after controlling for state and trait levels of positive and negative affect (e.g., McCullough et al. 2007). We therefore hypothesize that both these processes are relevant in the case of the particular interpersonal transgression that we focus on here: an imagined betrayal.

Willingness to forgive is part of the process by which people become less negatively and more positively disposed towards a transgressor (McCullough et al. 2000). It can facilitate cognitive, emotional, and behavioral changes in victims that lead to a decrease in negative feelings of hate and revenge and an increase in more positive feelings such as understanding and compassion (Enright and Coyle 1998). We expected that willingness to forgive has a mediating function for the following reasons: First, we assume a positive connection between self-compassion and willingness to forgive. Self-compassionate people are described as being kind to themselves, which seems to facilitate self-forgiving in the face of failure. When faced with personal adversity, they should be more likely to forgive their own faults and engage in self-talk that can be characterized as positive and forgiving as they aim to maintain a loving and patient approach towards themselves (Allen and Leary 2010). Neff and Pommier (2013) detected that this effect of self-compassion is also applicable to interpersonal situations. Hence, self-compassion should also foster a forgiving approach when problems occur in interpersonal situations such as an actual or potential betrayal. Indeed, recent research is in line with this idea. A robust negative association has been found between undergraduates’ lack of forgiveness and their self-compassion (Chung 2016). Second, we assume a negative relationship between willingness to forgive and both jealousy types. Recent research (Murphy et al. 2015) on adolescents already demonstrated a robust negative association between friendship jealousy and trait forgiveness, and both constructs seemed to be similarly explained by negative emotionality, though reverse coded for forgiveness. Willingness to forgive helps to transform the values of emotions and cognitions against a transgressor from negative to more positive. Thus, in the particular situation of a potential betrayer, willingness to forgive could be associated with experiencing less negative emotions when a partner engages in unfaithful behaviors (reactive jealousy) and with lower suspiciousness and rumination about a potential threat (anxious jealousy).

Anger rumination is defined as a tendency to focus attention on angry moods, spontaneously relive moments of anger, and repetitively think over the causes and consequences of anger episodes (Sukhodolsky et al. 2001). The following arguments outline the expected mediation: First, we assume a negative relationship between self-compassion and anger rumination. Self-compassion decreases negative emotions such as anger in reaction to conflict, because its mindfulness aspect prevents people from catastrophizing and being carried away by their negative emotions (Neff et al. 2007a), and it helps to reduce rumination (Yarnell and Neff 2012). Recent research in a sample of young adults (Fresnics and Borders 2017) provided empirical support for this hypothesis. Here, self-compassion was negatively related to anger rumination. Second, we assume positive associations between anger rumination and both jealousy types. Numerous theorists have consistently seen anger as a prominent component of jealousy (e.g., Buunk 1995; Sabini and Green 2004). Therefore, anger should particularly shape emotional reactions (reactive jealousy) to a relationship threat. Further, cognitive jealousy has been shown to be positively related to individuals’ worrying about their romantic relationship and their partners’ actions (Elphinston et al. 2013). So we expect that the ruminating aspect of anger rumination repeatedly focuses attention on angry moods and ostensible relationship threats.

The Present Study

The aim of the present study was to examine whether a unique negative association between self-compassion (total score) and different types of romantic jealousy exists. In particular, we included reactive jealousy to assess more rational reactions to an imagined relationship threat and anxious jealousy as a measure for more problematic and unhealthy jealousy reactions that can also occur in the absence of a potential relationship threat and can have destructive effects on relationship outcomes. We also performed exploratory analyses of the relationships of the self-compassion subscales with romantic jealousy. Additionally, we looked at willingness to forgive and anger rumination as possible mediators explaining the associations that we hypothesized for the self-compassion total score. We tested all of our hypotheses on adults in a romantic relationship.

We formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Self-compassion (total score) predicts lower levels of reactive jealousy (H1a) and anxious jealousy (H1b).

Hypothesis 2: Willingness to forgive and anger rumination mediate the links between self-compassion and reactive jealousy (H2a) and anxious jealousy (H2b).

Taking an exploratory approach, we studied the effects of the self-compassion subscales on romantic jealousy. We suspect the mindfulness (vs. over-identification) component to be negatively (vs. positively) predictive for reactive jealousy, while the self-kindness (vs. self-judgment) and common humanity (vs. isolation) components should be negatively (vs. positively) predictive for anxious jealousy.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 185 German-speaking adults (65.4% female, 34.6% male) who were in a romantic relationship. Their age ranged from 18 to 56 years (M = 32.28, SD = 12.14). About half of them were working (47.6%), 3.2% reported being unemployed, 44.3% were university students enrolled in different courses at the University of Halle, and 4.9% did not report their status. All participants were self-reported heterosexuals involved in romantic relationships. 27.0% were married, 66.5% were engaged in a serious relationship, and 6.5% were in a more casual relationship.

Measures were assessed via self-reports and questionnaires. Participants first provided demographic information (e.g., age, gender, work status, relationship experience), and then they completed a self-compassion measure. To introduce participants to jealousy-related topics, they were asked to think of their romantic relationship and imagine their partners had just started behaving in a withdrawn and suspicious way (Buss et al. 1992; Tagler 2010). Afterwards, participants completed the romantic jealousy and mediator measures. Data were collected in an online survey using SoSci Survey (Leiner 2014) whereby participants were recruited via undergraduate university students who were asked to distribute the survey among their friends and family members in order to receive credit towards their studies. Collecting data in online-studies has been often criticized for several reasons (e.g., for selecting an unrepresentative sample). Nevertheless, research has demonstrated that data collected online are comparable to those collected in conventional ways (Gosling et al. 2004). We designed and conducted our study according to the code of good practice in internet-delivered testing (Coyne and Bartram 2006).

Measures

Self-Compassion

Self-compassion was assessed by using a German version (Hupfeld and Ruffieux 2011) of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003a). The scale consists of 26 items to which participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale. An index of self-compassion was created by averaging all items. The SCS had high internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). Similar coefficients have been reported for the German version before, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 (Hupfeld and Ruffieux 2011). The internal consistencies and items of the six subscales comprising self-compassion were as follows: self-kindness (0.80; 5 items, e.g., “I’m kind to myself when I’m experiencing suffering.”), self-judgment (0.71; 5 items, e.g., “I’m disapproving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies.”), common humanity (0.69; 4 items, e.g., “When I feel inadequate in some way, I try to remind myself that feelings of inadequacy are shared by most people.”), isolation (0.79; 4 items, e.g., “When I fail at something that’s important to me, I tend to feel alone in my failure.”), mindfulness (0.69; 4 items, e.g., “When something upsets me I try to keep my emotions in balance.”), and over-identification (0.72; 4 items, e.g., “When I’m feeling down I tend to obsess and fixate on everything that’s wrong.”).

Romantic Jealousy

Reactive and anxious types of jealousy were assessed by using a single scale for each type, developed by Buunk (1997). Reactive jealousy (emotional) is indicated by the severity of distress people would experience if their partners were intimately engaged with another person (e.g., “How upset would you be if your partner would kiss someone else.”). Anxious jealousy (cognitive) assesses the extent that participants worry about their partner being unfaithful (e.g., “I am afraid that my partner is sexually interested in someone else.”). Each scale consists of five items on 5-point Likert scales. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients in the present study were 0.82 for reactive and 0.90 for anxious jealousy. The correlation between reactive and anxious jealousy was r = 0.41, p < 0.001.

Willingness to Forgive

We measured the tendency to forgive another person with the Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Inventory (McCullough et al. 2000) using the German version by Werner and Appel (2014). This scale consists of 12 reverse-coded items (e.g., “I’ll make him/her pay.”). Responses were given on a 5-point scale. Werner and Appel (2014) reported reliabilities for the scale between 0.83 and 0.86. In our study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Anger Rumination

The tendency to focus attention on angry moods, to spontaneously relive moments of anger, and to think over the causes and consequences of anger episodes was measured with the Anger Rumination Scale (ARS; Sukhodolsky et al. 2001). The scale consists of 19 items (e.g., “I re-enact the anger episode in my mind after it has happened.”). Responses were given on a 4-point scale. Sukhodolsky et al. reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.93. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.90.

Analytic Strategy

We used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences v. 20 (SPSS 20) to compute all analyses. In addition, we ran mediational analyses using the PROCESS (model 4) script by Hayes (2013), which enabled us to estimate total, direct, and indirect effects in simple and multiple parallel mediator models. Bootstrap confidence intervals were also implemented to test the statistical significance of the indirect effects. Bootstrapping is a resampling method generating an estimation of the sampling distribution of a statistic from the observed dataset. We used 10,000 bootstrap samples to calculate bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Point estimates of the indirect effects were considered significant when zero was not included in the 95% confidence intervals. Our sample size met the guidelines for detecting mediation effects by using bootstrapping (see Fritz and MacKinnon 2007). Consistent with openness and transparency in science, we have reported all information concerning determination of our sample size, data exclusion, and measurements (Simmons et al. 2012).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among the tested variables are displayed in Table 1. The self-compassion total score was inversely related to both types of jealousy. Correspondingly, results of the self-compassion subscales (except common humanity) revealed significant relationships to all types of jealousy, and all correlations were in the expected directions. The negative subscales (self-judgment, isolation, over identification) were positively related, and the positive subscales (self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness) were negatively related to jealousy, but the negative subscales were more strongly related than the positive subscales.

Both mediator variables, willingness to forgive and anger rumination, were significantly related to self-compassion total score and to both jealousy types in the expected directions. The negative correlation between the mediators was significant and in line with previous results (e.g., McCullough et al. 2007).

Women had on average higher reactive and anxious jealousy scores than men, which confirms previous results (e.g., Buunk 1997; Dijkstra and Barelds 2008). Age was negatively related to both types of jealousy, indicating that older people experience less jealousy. Further, the self-compassion scales (the total and the subscales) showed weak correlations with age and gender (r ranging from −.26 to .27) supporting former results that higher self-compassion levels can be found in males and older people (Neff 2003a; Souza and Hutz 2016; Yarnell et al. 2015). Therefore, we controlled for gender and age in all of the analyses when predicting romantic jealousy from the self-compassion scales.

Testing the Association between Self-compassion scales (total and subscales) and Romantic Jealousy

Hierarchical regression analyses were performed with reactive and anxious jealousy as criterion variables (Table 2). For each analysis, age and gender were entered in step 1 and the self-compassion scales (total or subscales) in step 2. Results for the self-compassion total score revealed that self-compassion was negatively related to both types of romantic jealousy (βs ranging from −.27 to −.39, all ps < .001) after having entered the control variables. The unique effect of self-compassion confirmed hypotheses 1a and 1b. In sum, reactive jealousy (emotional jealousy component) is higher in low self-compassionate people and in women, while anxious jealousy (cognitive jealousy component) is higher in low self-compassionate people and in younger people.

To shed light on the associations of the self-compassion subscales with romantic jealousy, we again conducted hierarchical regression analyses controlling for gender and age in step 1 and entered the subscales in step 2 (see Table 2). In the reactive jealousy model, mindfulness was the only significant predictor, while in the anxious jealousy model self-kindness, common humanity, isolation, and mindfulness were predictive. Compared with the anxious jealousy model (R2 = 0.30), the predictive model with reactive jealousy as dependent variable was weaker overall (R2 = 0.14). The fact that more self-compassion subscales were predictive of anxious jealousy perhaps indicates that this form of jealousy is influenced by a wider variety of forces. This is partly consistent with previous results on well-being that suggest that self-compassion consists of more than just mindfulness (Bear et al. 2012).

Testing Mediation Models of the contribution of Willingness to Forgive and Anger Rumination to the Association between Self-compassion (total score) and Romantic Jealousy

Because our two mediators were significantly correlated with each other (r = −.29, p < .001), we calculated the mediation analyses with two parallel mediators. These analyses tested whether the effects of self-compassion (total score) on romantic jealousy occur via willingness to forgive and/or anger rumination. All analyses included our covariates (gender and age). Table 3 shows the indirect effect of self-compassion on reactive jealousy via willingness to forgive (Model 1, Table 3) with the 95% bootstrap interval (BootCI) not including zero (p < .05). Thus, willingness to forgive significantly mediated the relationship between self-compassion (total score) and reactive jealousy. Contrary, no mediating effect was found for anger rumination.

However, there was no effect or combination of effects that could completely mediate the effect of self-compassion on reactive jealousy (the c’ path remained significant). The significant mediation effect that we found for willingness to forgive was very weak, and the direct path from self-compassion to reactive jealousy remained significant. Therefore, our hypothesis 2a was only partially supported.

Neither willingness to forgive nor anger rumination significantly mediated the association between self-compassion and anxious jealousy. Therefore, our hypothesis 2b was not supported.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are that high self-compassionate individuals experience lower levels of reactive jealousy (emotional) in a jealousy-provoking scenario, that is, when imagining their partner romantically involved with another person. They also experience lower levels of anxious jealousy (cognitive) in the absence of a rational relationship threat. Moreover, the effects of self-compassion on reactive jealousy were partially mediated by willingness to forgive, while among our set of parallel mediations (willingness to forgive, anger rumination) no significant mediator was found for the association between self-compassion and anxious jealousy. Willingness to forgive was more superordinate in shaping reactive jealousy than was anger rumination.

The negative association of self-compassion with reactive jealousy, the emotional jealousy component, replicates and extends the finding that self-compassion is related to lower levels of emotional intensity and turmoil when reacting to conflicts in romantic relationships. This effect has been previously reported for a more general range of romantic conflict situations (e.g., Kelly et al. 2009; Yarnell and Neff 2012). We detected this effect for a particular conflict situation, experiencing romantic jealousy, which is recognized as a frequently occurring romantic conflict (Zusman and Knox 1998) often highly charged with emotions. Physiological studies offer an explanation for the reduced experience of emotional reactions in high self-compassionate people. For example, individuals trained in self-compassion have been found to have reduced levels of the stress hormone cortisol (Rockcliff et al. 2008). The results of our mediation analyses shed more light on why this reduced emotional reaction of high self-compassionate people should be related in particular to experiencing lower levels of reactive jealousy in a hypothetical scenario of cheating behavior. Willingness to forgive seems to be important in mediating this effect. Arguably, because willingness to forgive helps to transform negative feelings towards a transgressor into positive feelings, it accompanies decreased negative feelings, which in turn should lower reactive jealousy, that is, the intensity and turmoil of emotional reactions when imagining being confronted with a relationship threat. This reasoning is also in line with clinical intervention studies that support the assumption that reactive jealousy can be best helped by decision-based forgiveness and less by using cognitive-behavioral techniques aimed at changing cognitions. While the forgiveness approach should enable people to act, the latter is less likely to be helpful in coping with the overwhelming emotions (DiBlasio 2000).

Our results also revealed a negative relationship between self-compassion and the cognitive jealousy component, anxious jealousy. Being kind and understanding towards oneself appears to be associated with lower levels of suspicion about a partner’s possible infidelity. This result confirms our assumption that people high in self-criticism and negative thinking (low self-compassion) who perceive a potential betrayal as an impending negative life event, tend to engage in rumination. Moreover, a potential betrayal can be one reason to act verbally aggressively and critically towards a partner, which is related to lower levels of self-compassion. Our results suggest that self-compassion is associated with less worrying about being deceived by one’s partner, which means less anxious jealousy. This interpretation is also consistent with jealousy intervention studies suggesting that cognitive-behavioral techniques work best in anxious jealousy, by changing irrational beliefs and distrust (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007).

What does reduced romantic jealousy entail for relationship satisfaction? Greater anxious jealousy has been consistently associated with lower relationship satisfaction (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007; Carson and Cupach 2000), but Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra (2007) found the opposite pattern for reactive jealousy; greater reactive jealousy was associated with higher relationship satisfaction. It may be the case that partners interpret reactive jealousy as a sign of caring, and reactive jealousy may even be intentionally induced in order to enhance the relationship. This finding has important implications for the interpretation of our results; if self-compassion reduces reactive jealousy, it ought also to lead to less relationship satisfaction for the partners of self-compassionate people. However, this does not seem to be the case. The partners of high self-compassionate people rate their partners as more caring, accepting and autonomy granting, and less controlling and verbally aggressive (Neff and Beretvas 2012). Do self-compassionate people therefore use alternative strategies to enhance their relationships? Perhaps self-compassionate people are helped by their cooperative conflict resolution style (Yarnell and Neff 2012), since it has been found that cooperative people are more attractive as partners (Farrelly et al. 2007). Future research should assess the strategies self-compassionate people use to increase relationship satisfaction, for example by testing whether their more cooperative conflict resolution style is associated with greater attractiveness as partners.

Notwithstanding the uncertainty concerning its consequences for relationship satisfaction, we found a significant direct effect of self-compassion on both types of romantic jealousy even after accounting for mediation. The self-compassion subscale analysis provides some additional insight for this result. The self-compassion component that was most strongly related to reactive jealousy was mindfulness. Maintaining a more balanced perspective (mindfulness) when imagining being deceived by a partner might be helpful in reducing the emotional level in reactive jealousy. This partly fits our speculations that the self-compassion components related to dealing with the amount of paying attention to one’s suffering (mindfulness and over-identification) are predominantly predictive for emotional jealousy. However, over-identification (the opposite of mindfulness) did not contribute to feelings of reactive jealousy. The cognitive jealousy type, anxious jealousy, was strongly predicted by isolation and self-kindness. Feeling less isolated and disconnected from others (isolation) and soothing and comforting oneself (self-kindness) when ruminating about the possibility of being deceived by one’s partner might be helpful in reducing the anxious and suspicious cognitions related to jealous thoughts. Additionally, mindfulness and common humanity (the opposite of isolation) appear to be applicable in explaining cognitive jealousy. However, we did not observe a consistent pattern in the subscale scores explaining jealousy reactions over both jealousy responses. This is not surprising, given that we examined different types of jealousy, one being an emotion that accompanies a rational reaction, the other being more cognitive and involving only suspicions. Given the lack of research investigating the impact of self-compassion subscales on any other interpersonal outcome, we cannot compare or integrate our results with previous findings. However, our results are contrary to self-compassion subscale studies of the predictors of angry reactions; only over-identification was predictive of anger (Fresnics and Borders 2017). Therefore, a follow-up study should test our speculations about the distinct predictive powers of the self-compassion subscales (cognitive, emotional, amount of attention).

Considered in the light of the socio-cognitive theory of jealousy (Harris 2003), perhaps self-compassion reduces jealousy because it enables people to feel more comfortable with norm violations, and because self-compassionate individuals see romantic rivals as less threatening to their self-image. Harris (2003) argued that what is perceived as threat to the self will be largely shaped by one’s cultural values. Hence, a self-compassionate person might feel less uncomfortable if the partner ignores these cultural values. Coherently, a buffering effect of self-compassion on the subjective well-being of people who do not match societal expectations has been found (Keng and Liew 2017). Therefore, for follow-up studies we suggest to explore the interplay between self-compassion and sociocultural expectations in predicting emotion regulation when faced with a relationship threat.

Limitations

Our study revealed some promising results for the link between self-compassion and romantic jealousy. Nonetheless, it has some limitations. First, we did not control for more fundamental features, such as attachment style, which could possibly explain the connection between self-compassion and jealousy, given that attachment style is central to relationship behaviors. However, Neff and Beretvas (2012) reported that attachment style failed to predict numerous relationship outcomes after controlling for self-compassion. Furthermore, assessing the effects of less global characteristics, such as self-compassion, is more practical and perhaps more promising, because they are easier to alter compared to more fundamental characteristics.

Second, our cross-sectional design, though well-suited to studying mediation effects, does not allow conclusions about the direction of causation. Future research should also use longitudinal designs to establish the direction of causation. Longitudinal designs are also better suited for testing interventions.

Another limitation, which is more of a general problem for research on romantic jealousy, is that the assessment of reactive jealousy is based on participants imagining their partner’s cheating behavior. This method might not represent how self-compassion shapes jealous responses to real-life cheating behaviors. Future research could build on the work of Sbarra et al. (2012), who already demonstrated significant adaptive effects of self-compassion for real-life relationship threats (e.g., marital separation). Self-compassion was positively associated with short- and long-term psychological adjustment in divorced adults, such as less emotional intrusions and somatic hyperarousal, when confronted with their divorces.

In our study, the participants are aged between 18 and 56 years and have a wide and various spectrum of relationship experience. Thus, future studies should also include contextual factors, such as age of partners, length of relationship, relationship type, and whether the couple is raising children.

Follow-up studies should also study self-compassion and jealousy in couples, by examining both partners’ reports to assess the effect of actor’s and partner’s self-compassion on experiencing romantic jealousy (Actor-Partner-Interdependence Model; Kenny 1996). Research has already shown that partners’ jealousy responses affect the responses of their mates (Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra 2007).

Implications

Adding interventions that enhance self-compassion (e.g., Mindful Self-Compassion Program; Neff and Germer 2013) to established treatments in couple’s therapy offers promising practical solutions. As our results suggest, self-compassion is adaptively related to forgiveness and anger rumination. Thus, an enhancement of self-compassion might augment forgiveness and decrease anger rumination, which in turn could foster other psychological and physiological benefits (e.g., well-being, cardiac symptoms; Patton 2013; Rockcliff et al. 2008). Additionally, as suggested by Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra (2007) and partly supported by our mediation analysis, different jealousy types can be best helped with different techniques. To overcome the intensity of reactive jealousy, one promising approach is to work on willingness to forgive directly by helping people in decision-based forgiveness of the partner’s infidelity at the beginning of treatment. This approach could empower people to work on their relationship problems (DiBlasio 2000). The intensity of anxious jealousy is best lowered by working on rumination directly, with cognitive-behavioral techniques to address irrational beliefs and distrust.

References

Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x

Barelds, D. H. P., & Barelds-Dijkstra, P. (2007). Relations between different types of jealousy and self and partner perceptions of relationship quality. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 14(3), 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.532

Bear, R. A., Lykins, E. L. B., & Peters, J. R. (2012). Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of psychological wellbeing in long-term meditators and matched nonmeditators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.674548

Bringle, R. G., & Buunk, B. (1985). Jealousy and social behavior: A review of person, relationship, and situational determinants. In P. Shaver (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology (pp. 241–264). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Brion, J. M., Leary, M. R., & Drabkin, A. S. (2014). Self-compassion and reactions to serious illness: The case of HIV. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(2), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312467391

Buss, D. M. (1994). The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating. New York: Basic Books.

Buss, D. M., Larsen, R. J., Westen, D., & Semmelroth, J. (1992). Sex differences in jealousy: Evolution, physiology, and psychology. Psychological Science, 3, 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00038.x

Buunk, B. P. (1995). Sex, self-esteem, dependency and extradyadic sexual experience as related to jealousy responses. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(1), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595121011

Buunk, B. P. (1997). Personality, birth order and attachment styles as related to various types of jealousy. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(6), 997–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00136-0

Buunk, B. P., & Dijkstra, P. (2004). Jealousy as a function of rival characteristics and type of infidelity. Personal Relationships, 11(4), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00089.x

Buunk, B. P., & Dijkstra, P. (2006). Temptations and threat: Extradyadic relationships and jealousy. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 533–556). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carson, C. L., & Cupach, W. R. (2000). Fueling the flames of the green-eyed monster: The role of ruminative thought in reaction to romantic jealousy. Western Journal of Communication, 64(3), 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570310009374678

Chung, M. S. (2016). Relation between lack of forgiveness and depression: The moderating effect of self-compassion. Psychological Reports, 119(3), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116663520

Coyne, I., & Bartram, D. (2006). Design and development of the ITC guidelines on computer-based and internet-delivered testing. International Journal of Testing, 6(2), 133–142.

DiBlasio, F. A. (2000). Decision-based forgiveness treatment in cases of marital infidelity. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 37(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087834

Dijkstra, P., & Barelds, D. P. (2008). Self and partner personality and responses to relationship threats. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1500–1511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.06.008

Elphinston, R., Feeney, J., Noller, P., Fitzgerald, J., & Connor, J. P. (2013). Romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction: The costs of rumination. Western Journal of Communication, 77, 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2013.770161

Enright, R. D., & Coyle, C. T. (1998). Researching the process model of forgiveness within psychological interventions. In E. L. Worthington (Ed.), Dimensions of forgiveness: Psychological research and theological perspectives (pp. 139–161). Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press.

Farrelly, D., Lazarus, J., & Roberts, G. (2007). Altruists attract. Evolutionary Psychology, 5, 313–329.

Fisher, H. (2000). Lust, attraction, attachment: Biology and evolution of the three primary emotion systems for mating, reproduction, and parenting. Journal of Sex Education & Therapy, 25(1), 96–104.

Fresnics, A., & Borders, A. (2017). Angry rumination mediates the unique associations between self-compassion and anger and aggression. Mindfulness, 8(3), 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0629-2

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2843527/.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93

Harris, C. R. (2003). A review of sex differences in sexual jealousy, including self-report data, psychophysiological responses, interpersonal violence, and morbid jealousy. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(2), 102–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0702_102-128

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4

Hupfeld, J., & Ruffieux, N. (2011). Validation of a German version of the self-compassion scale (SCS-D). Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 40, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000088

Kelly, A. C., Zuroff, D. C., & Shapira, L. B. (2009). Soothing oneself and resisting self-attacks: The treatment of two intrapersonal deficits in depression vulnerability. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-008-9202-1

Keng, S. L., & Liew, K. W. L. (2017). Trait mindfulness and self-compassion as moderators of the association between gender nonconformity and psychological health. Mindfulness, 8(3), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0639-0

Kenny, D. A. (1996). Models of nonindependence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13, 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132007

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leiner, D. J. (2014). SoSci Survey (Version 2.4.00-i) [computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.sosciurvey.de.

Mathes, E. W. (1991). A cognitive theory of jealousy. In P. Solvey (Ed.), The psychology of jealousy and envy (pp. 52–79). New York: Guilford.

McCullough, M. E., Pargament, K. I., & Thoresen, C. E. (2000). The psychology of forgiveness: History, conceptual issues, and overview. In M. E. McCullough, K. I. Pargament, & C. E. Thoresen (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 1–14). New York: Guilford. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2012.741897

McCullough, M. E., Bono, G., & Root, L. M. (2007). Rumination, emotion, and forgiveness: Three longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 490–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.490

Miller, R. B., Nunes, N. A., Bean, R. A., Day, R. D., Falceto, O. G., Hollist, C. S., & Fernandes, C. L. (2014). Marital problems and marital satisfaction among Brazilian couples. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 42(2), 153–166.

Murphy, T. P., Laible, D. J., Augustine, M., & Robeson, L. (2015). Attachment's links with adolescents' social emotions: The roles of negative emotionality and emotion regulation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 176(5), 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2015.1072082

Neff, K. D. (2003a). Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D. (2003b). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K. D. (2009). Self-compassion. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 561–573). New York: Guilford Press.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Neff, K. D. (2016). Does self-compassion entail reduced self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification? A response to Muris, Otgaar, and Petrocchi (2016). Mindfulness, 7(3), 791–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0531-y

Neff, K. D., & Beretvas, S. N. (2012). The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self and Identity, 12, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.639548

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923

Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2013). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and Identity, 12, 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.649546

Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y. P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity, 4(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000317

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K., & Rude, S. S. (2007a). Self-compassion and its link to adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2007b). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 908–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.08.002

Patton, B. (2013). The role of forgiveness in mediating feelings of betrayal within older adult romantic relationships. GRASP: Graduate Research and Scholarly Projects, 9, 16–17.

Pfeiffer, S. M., & Wong, P. T. P. (1989). Multidimensional jealousy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6, 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/026540758900600203

Rockcliff, H., Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Lightman, S., & Glover, D. (2008). A pilot exploration of heart rate variability and salivary cortisol response to compassion-focused imagery. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 5, 132–139.

Sabini, J., & Green, M. C. (2004). Emotional responses to sexual and emotional infidelity: Constants and differences across genders, samples, and methods. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(11), 1375–1388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264012

Sbarra, D. A., Smith, H. L., & Mehl, M. R. (2012). When leaving your ex, love yourself observational ratings of self-compassion predict the course of emotional recovery following marital separation. Psychological Science, 23, 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429466

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2012, October 14). A 21 Word Solution. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2160588.

Souza, L. K. D., & Hutz, C. S. (2016). Self-compassion in relation to self-esteem, self-efficacy and demographical aspects. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 26(64), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272664201604

Sukhodolsky, D. G., Golub, A., & Cromwell, E. N. (2001). Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00171-9

Tagler, M. J. (2010). Sex differences in jealousy: Comparing the influence of previous infidelity among college students and adults. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610374367

Werner, R., & Appel, C. (2014). Deutscher Vergebungsfragebogen [German Forgiveness scale]. In D. Danner & A. Glöckner-Rist (Eds.), Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen [Collection items and scales for social science]. https://doi.org/10.6102/zis56.

Yarnell, L., & Neff, K. D. (2012). Self-compassion, interpersonal conflict resolutions, and well-being. Self and Identity, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.649545

Yarnell, L. M., Stafford, R. E., Neff, K. D., Reilly, E. D., Knox, M. C., & Mullarkey, M. (2015). Meta-analysis of gender differences in self-compassion. Self and Identity, 14(5), 499–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1029966

Zusman, M. E., & Knox, D. (1998). Relationship problems of casual and involved university students. College Student Journal, 32, 606–609.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tandler, N., Petersen, LE. Are self-compassionate partners less jealous? Exploring the mediation effects of anger rumination and willingness to forgive on the association between self-compassion and romantic jealousy. Curr Psychol 39, 750–760 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9797-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9797-7