Abstract

This study aimed to examine the mediating role of rumination on the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety–depression among a sample of 405 elderly adults from China. The participants completed a questionnaire packet containing neuroticism, ruminative response, and depression and anxiety scales. Path analysis was adopted to test the mediating effects, and bootstrap methods were applied to assess the magnitude of indirect effects. Results showed that anxiety and depression were positively correlated with neuroticism and rumination. Neuroticism positively influenced the symptoms of anxiety and depression, and this relationship was partially mediated by rumination. This study expounded the mediating role of rumination underlying the positive association between neuroticism and anxiety–depression in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health problems are a key factor that largely influences older adults’ health and quality of life (Hirani et al. 2014). Their mental health can be indicated by anxiety and depression that function as negative indicators (Painter et al. 2012). Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in the older population. An even larger proportion of older adults suffer from numerous anxiety and depressive symptoms that impair functioning and quality of life but do not satisfy the criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis (Djernes 2006; George 2011; Vink et al. 2008). The incidence of anxiety–depression symptoms among older adults range from 10% to 23% (Hull et al. 2013; Vink et al. 2008; Yohannes et al. 2000). Anxiety and depression are frequently comorbid in older adults when interactions between advancing age and comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions are considered. Studies have shown that anxiety and depressive disorders are common among older-aged individuals, although they are less common among young adults (George 2011; Vink et al. 2008; Wolitzky-Taylor et al. 2010).

With the largest population in the world, China faces problems related to an aging society population. According to China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs, the population of people aged over 60 years by the end of 2015 reached 222,000,000, which accounts for about 15.5% of China’s total population and nearly one-quarter of the world’s elderly population (Zhang and Zhang 2015). Mental health problems are critical for Chinese older adults. Jiang et al. (2004) enrolled several elderly people in Beijing as participants in a study and determined that 13.7% of them manifest depressive symptoms. Ma et al. (2008) reported that 16.9% of elderly people in China’s urban areas suffer from depressive symptoms. The vulnerability factors of anxiety–depression among the elderly include social cognitive bias, personality, and frustration, which can aggravate older adults’ negative emotions (Jo et al. 2007).

Neuroticism and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

Personality factors predispose older adults to depression or anxiety. Neuroticism is a relatively stable psychological structure that has been considered as a personality factor relevant to psychopathology, particularly anxiety and depression. Neuroticism is a persistent personality trait that places an individual in the state of experiencing negative emotions, such as anger, depression, anxiety, and guilt (Griffith et al. 2010). Individuals with high neuroticism pay considerable attention to negative life events, which invoke negative emotional experiences. Several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have found good support for the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety–depression symptoms (Hansell et al. 2012). A 10-year longitudinal study has shown that high neuroticism is directly related to the development of clinical depression, and this relationship can predict the first occurrence of depression (K. S. Kendler et al. 2006). Santor and Rosenbluth (2005) reported that neuroticism can significantly predict depression. Individuals with high grades of neuroticism dimension likely overestimate stressful events and tend to experience considerable anxiety toward pressure sources in daily life.

Although studies have shown that neuroticism is an important influencing factor of anxiety–depression, studies have presented different views on processes by which neuroticism is expressed. Cognitive theory stresses the negative processing on the state of mind, which explains why individuals with high neuroticism can easily suffer from anxiety–depression. Individuals with high neuroticism often emphasize negative information related to themselves, and this cognitive processing can play a mediating role between neuroticism and anxiety–depression (Kardum and Krapić 2001). Constant self-focused attention, such as rumination, is an expressive form of these processing approaches (Mor and Winquist 2002).

Mediating Role of Rumination between Neuroticism and Anxiety–Depression Symptoms

Rumination is the compulsively focused attention on the symptoms of one’s distress and its possible causes and consequences as opposed to its solutions (Nolen-Hoeksema 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema and Jackson 2001). Ruminative individuals continuously think about the reasons and results of negative events and the feelings that these events elicit, but they do not care about solving their problems. Therefore, this concept is a negative approach of thinking and cognitive style (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). Several studies have examined the relationship between neuroticism and rumination. For example, Muris et al. found that neuroticism and rumination are positively correlated (Muris et al. 2005). Roelofs et al. determined that neuroticism in clinical patients with depression can significantly affect rumination (Roelofs et al. 2008).

Some researchers argued that ruminative response styles may be considered a cognitive manifestation of neuroticism. Individuals with high neuroticism are likely nervous, excited, sentimental, sensitive, and easily frustrated. Moreover, they focus on themselves, tend to experience confusion and decision-making difficulties, and wallow in negative events (Griffith et al. 2010). This condition emphasizes that neuroticism may be positively correlated with rumination. Neuroticism is a type of personality trait, whereas rumination is a type of cognitive style. Personality is universally stable and can influence an individual’s way of thinking and cognitive style (Steger et al. 2008).

Rumination is a sensitive factor of mental health, and it maintains an individual’s negative effect and increases the possibility of an individual’s anxiety and depression symptoms. For example, Nolen-Hoeksema and Jackson (2001) determined that rumination is highly correlated with depression (r = 0.62) in adults. Papadakis et al. (2006) also found a positive correlation between rumination and depression in children. Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (1994) documented in a longitudinal study that rumination can significantly predict depression after an individual experiences traumatic events. Rumination is also relevant to anxiety. Harrington and Blankenship (2002) suggested that the rumination content is involved in the self, and self-focus is highly correlated with anxiety. Therefore, rumination is likely related to anxiety. The correlation coefficient between rumination and depression is 0.33, whereas the correlation coefficient between rumination and anxiety is 0.32. If anxiety is controlled, then the partial correlation between rumination and depression is 0.20, whereas the partial correlation between rumination and anxiety is 0.17 (Harrington and Blankenship 2002). Unlike less anxious individuals, individual with high anxiety tend to apply rumination in social scenarios but hardly utilize other strategies (2005), and this condition is one of the reasons that cause maladaptation among these individuals. Kocovski et al. (2005) invited clinical patients with anxiety disorder to participate in a cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and determined that all of the participants displayed high rumination after they experienced performance contexts, such as delivering a speech before the public, and social interaction scenarios, such as one-on-one conversations.

Purpose of the Current Study

A meditational model in which neuroticism is associated with rumination, which in turn is related to symptoms of depression and anxiety. This meditational model is supported by evidence related to undergraduates and adolescents at risk for depression (Kuyken et al. 2006). However, no existing research discusses the relationship among neuroticism, rumination, and anxiety–depression in older adults. The current study sought to investigate the meditational effects of a ruminative response style on the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety–depression symptoms in older adults, who are sensitive to their living conditions because of the changes in their physical functions and living conditions. They retire at home and spend considerable time for reflection and memory. Hence, the current study enrolled older adults as participants and investigated the relationship among these variables. This study presents the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 - Neuroticism is positively associated with rumination in older adults.

Hypothesis 2 - Neuroticism is positively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety in older adults.

Hypothesis 3 - Rumination is positively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety in older adults.

Hypothesis 4 - The link between neuroticism and symptoms of anxiety–depression is reduced when the mediating variables of rumination are controlled.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

A total of 405 participants aged 61 years and above (179 men, 44.20%; 226 women, 55.80%; Table 1) were recruited through public announcements, and the participants could respond if they were interested in six large communities in Shanghai. The participants who suffered from poor health conditions, experienced difficulty in conversing, and lived in nursing homes were excluded. The age of the participants ranged from 61 years to 72 years with a mean of 65.14 years (SD = 2.35). All of the participants were married and retired. Of the participants, 368 (90.86%) reported that they live with their spouses, children, or other relatives and 37 (9.14%) indicated that they live alone. All of the participants completed the questionnaires in their respective communities. All of the 405 questionnaires that were distributed and collected were valid. The participants were informed of the purpose and the voluntary nature of the study and were ensured anonymity for all responses given. Willing participants signed a consent form and returned the completed survey to the researcher. They also received a box of eggs as compensation. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Experimentation of Shanghai Normal University.

Instruments

Neuroticism Scale

Neuroticism scale is a sub-scale of Big-5 personality measures (Costa and McCrae 1992), and it includes 12 items. Items are rated from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 5 (very strongly agree). The examples of items from this form consist “I worry about things,” “I am much more anxious than most people,” and “I get upset easily.” The scores on this scale range from 12 to 60. High scores more likely interpret ordinary situations as threatening and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. The neuroticism scale, translated into Chinese by Cheung and Leung, exhibits good validity and reliability in Chinese populations (Cheung and Leung 1998). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the neuroticism scale was 0.79.

Ruminative Response Scale

The ruminative response scale (RRS) is designed to assess ruminative coping responses to depressed mood (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). This scale contains 22 items, and responses to each item are scored from 1 (“almost never”) to 4 (“almost always”). Some examples of items included “Think about how alone you feel” and “Go away by yourself and think about why you feel this way.” The scores on all of the items are added to obtain the total score, which ranges from 22 to 88; higher scores indicate higher levels of ruminative coping responses. The RRS has been translated into Chinese and has shown good internal consistency and validity (Chia and Graves 2016; Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the RRS was 0.91.

Self-Rating Depression and Anxiety Scale

The self-rating depression and anxiety scale, developed by Zung, is a self-report measure consisting of 40 items, which include two dimensions that measure depression and anxiety (Zung & Green, 1974). For each item, participants are asked to indicate how often they experienced the particular symptom over the last week. Each response ranges from 1 (“rarely or none of the time”) to 4 (“most or all of the time”). Examples of the items included “I feel down-hearted and blue,” “Morning is when I feel the best,” “I feel afraid for no reason at all,” “I can feel my heart beating fast.” This scale has been translated in Chinese and shows good validity and reliability (He et al. 2014; Kong et al. 2014). The scores on the depression and anxiety scales range from 20 to 80. High scores indicate high levels of depressive and anxious symptoms. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of depression and anxiety scales were 0.90 and 0.88 respectively.

Data Analysis

The descriptive statistics, correlations, and regression analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 17.0. This study adopted the bootstrapping method (1200 resamples) to provide bias-corrected and bias-accelerated confidence intervals as a test of statistical significance in AMOS 17.0. The criteria outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) provide a conceptual framework to facilitate examination of mediation; however, these do not include a test of statistical significance for the indirect effect of the mediator. Baron and Kenny suggested the Sobel test as appropriate: it tests the null hypothesis that the indirect effect is zero (Baron and Kenny 1986). However, the Sobel test assumes that the distribution of indirect effect is normal, which is seldom the case (Hayes 2009). Bootstrapping, or the nonparametric resampling of the data set to make repeated estimates, makes no such assumption (Black and Reynolds 2013; Preacher and Hayes 2008; Yu et al. 2016). Thus, after treating demographic variables, such as gender and living status, as control variables, regression statistics and results of the Sobel test are presented in this study.

Results

General Findings

Table 2 shows the means, descriptive statistics, and inter-correlations of the variables used. When Table 2 was examined, significant correlations between neuroticism, rumination, and anxiety–depression are observed. Neuroticism related positively to rumination (r = 0.38, p < 0.01), depression (r = 0.35, p < 0.01), and anxiety (r = 0.37, p < 0.01). On the other hand, rumination was found to be positively related to depression (r = 0.29, p < 0.01) and anxiety (r = 0.38, p < 0.01).

Table 3 showed the variable differences between male and female participants, and between participants living alone and with others. No significant gender difference in neuroticism (F = 0.07, p = 0.79), depression (F = 0.97, p = 0.32), and anxiety (F = 1.20, p = 0.27) is observed; however, female participants were found to be more ruminative than male participants (F = 11.32, p < 0.01). Further, significant differences are found between participants who live alone and with others in rumination (F = 3.94, p < 0.05), depression (F = 19.20, p < 0.01), and anxiety (F = 21.30, p < 0.01); this finding indicated that living status should be considered as a control variable in the path analysis. A marginally significant difference in neuroticism is also observed (F = 3.21, p = 0.07).

Mediating Effects of Rumination in the Link between Neuroticism and Symptoms of Depression–Anxiety

Following the mediation test rules introduced by Baron and Kenny, we tested the mediating role of rumination between neuroticism and anxiety–depression. Gender and living status were treated as control variables in all the regression models. Firstly, rumination was regarded as dependent, and neuroticism was regarded independent. The regression model was significant (Table 4). Depression was regarded as dependent, and neuroticism and rumination were introduced successively. Table 4 shows that from model 2, the standardized regression coefficient of neuroticism to depression was 0.33. However, when rumination was introduced, the regression coefficient decreased to 0.27. Sobel test result revealed a significant mediation effect (Sobel = 3.35, p < 0.05), which indicated that rumination mediated the impact of neuroticism on depression. Anxiety was also regarded as a dependent variable, and neuroticism and rumination were introduced successively. As shown in models 4 and 5, the standardized regression coefficient of neuroticism to anxiety was decreased from 0.35 to 0.25; Sobel test result also revealed a significant mediation effect (Sobel = 5.03, p < 0.05).

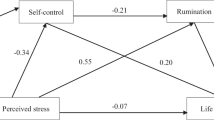

On the basis of our results, we conducted a path analysis on the whole model (Fig. 1). The mediating effects of rumination between neuroticism and anxiety–depression were further tested to determine their significance through bootstrap estimation. The results of bootstrap test revealed that the 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effects of neuroticism–rumination–depression (0.03–0.12) and neuroticism–rumination–anxiety (0.05–0.17) did not overlap with zero. Therefore, the mediating effects were significant.

Discussion

This research attempts to examine the relationships among neuroticism, rumination, and symptoms of anxiety–depression in older adults. Neuroticism positively predicted symptoms of anxiety–depression, and the relationships between neuroticism and symptoms of anxiety–depression were partially mediated by rumination as expected. In particular, symptoms of anxiety and depression increase as neuroticism increases in this model, and rumination plays a mediating role in that relation. This finding indicates that rumination is an important factor in the relationship between neuroticism and symptoms of anxiety–depression. In other words, elderly adults with higher neuroticism levels are more likely to be ruminative, inclined to be entangled with negative life events, and end up with higher levels of anxiety and depression. As described above, depression–anxiety symptoms may be detrimental to individuals and families of older adults. China has the largest population of older adults in the world, and many of these older adults suffer from depression–anxiety. More importantly, disparities in mental health care access in comparison with that to West, along with the influence of Confucius culture in emotional restraint, may prevent Chinese older adults from seeking timely psychological professional help. Notwithstanding the scope and severity of the issue, this study may have implications for preventing depression–anxiety for Chinese older adults.

Neuroticism is positively associated with rumination in older adults as expected. Neuroticism is a personal trait that is closely related to an individual’s emotional reaction tendency and emotional regulation capability. The main reflection of neuroticism is emotional instability and in-adaptation. Specifically, individuals who are neurotic tend to be over joyous or sad and indulge themselves in negative affect (Ormel et al. 2013). Rumination is a way of thinking by which people pay repetitive attention to negative moods and corresponding events. A personal trait can theoretically affect an individual’s cognitive style (Peng et al. 2014). Individuals with high neuroticism tend to be anxious and emotionally unstable. Therefore, they will be more likely to focus on negative information related to themselves, continuously be concerned about such information, rethink such information, and pick up the thinking habit of rumination (Muris et al. 2005; Yu et al. 2016). The results from this study show that older adults with high neuroticism can more easily fall into rumination in this manner. An alternative interpretation for this result might simply be the conceptual overlap with ruminative style and neuroticism in older adults (Leach et al. 2008).

Similar to the conclusions of a previous research, the present research also determined that both neuroticism and rumination are positively correlated with anxiety and depression in older adults (Griffith et al. 2010). Individuals with high neuroticism have a relatively stable tendency to experience a more negative affect in response to pressure; they are also likely to experience anger, nervousness, depression, and anxiety. These individuals can be impulsive, emotional, and highly dependent or unwilling to face reality (Servaas et al. 2013). More importantly, older adults with high neuroticism in their actual lives face a strong possibility of social deficit and low perception of support from their family or companions. Those older adults feel frustrated during their interaction with their family members or friends, which can lead to unfavorable interpersonal relationships (Merema et al. 2013). Older adults who have high levels of neuroticism may experience symptoms of anxiety and depression when interpersonal relationships dysfunction (Boyle et al. 2010). Empirical studies also confirmed that high scores on neuroticism are strongly related to depression and anxiety in later life (Denburg et al. 2009a, 2009b; Fiske et al. 2009). A large part of the relationship between neuroticism and depression–anxiety in older adults has been found to be a function of shared genetic vulnerability, suggesting that neuroticism can be viewed as an index of genetic risk for depression–anxiety (Kenneth S. Kendler et al. 2007; K. S. Kendler et al. 2006). Rumination is also associated with depression–anxiety across lifespan. Rumination can deteriorate or prolong depression and anxiety because it can force individuals to focus on themselves, especially on their negative feelings (Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2010; Pasyugina et al. 2015). These feelings can cause individuals to isolate themselves and indulge in rethinking all their annoying problems instead of attempting any possible resolution and taking action; furthermore, these feelings cause individuals to ponder over the consequence or cause of depression or anxiety symptoms rather than perform any constructive actions to alleviate such symptoms (Lyubomirsky et al. 2015). In older adults, ruminative coping styles has been associated with depression–anxiety (Garnefski and Kraaij 2006; Peng et al. 2013). Older adults with the cognitive habit of rumination will trap themselves into fighting against themselves or in any negative event in their lives (McLaughlin et al. 2014). These older adults will repetitively experience negative moods instead of solving problems, thereby aggravating their anxiety–depression symptoms.

This study focuses on the validation of the intermediary role of rumination in the effect of neuroticism on symptoms of depression and anxiety in elderly adults. Path analysis and Bootstrap methods confirmed the hypothesis of the current study, which provided an overall view on the relationships among neuroticism, rumination, and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Mohlman et al. 2012; Painter et al. 2012). In fact, older adults with high neuroticism are likely to be excessively sensitive and emotional, and they may strongly respond to any stimulus (Boyle et al. 2010; Denburg et al. 2009a, 2009b; Mohlman et al. 2012). Given their strong self-concern, these elderly adults will frequently re-think their negative living experiences, conduct continuous self-reflection, and repetitively experience negative affect (Hirani et al. 2014; Hull et al. 2013). Over time, they can acquire rumination, which is a type of cognitive style and thinking habit. Rumination prompts individuals to focus on the negative psychological symptoms, causes, and influences related to such symptoms (Chia and Graves 2016; Coyle and Dugan 2012; Denburg et al. 2009a, 2009b). Moreover, it forces older adults to negatively evaluate their conditions and distance themselves from their own standards, thereby aggravating negative affect, such as anxiety and depression (Barg et al. 2006; Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2010). As adults transition into later life cycles, they encounter many significant changes in their lives, taking retirement or reduced economic resources, physical health problems, and the loss of a spouse or other intimacy. Unsurprisingly, older adults suffer more symptoms of anxiety than younger adults. In addition, age-specific fears have been confirmed in older adults, such as worry of being a burden on others (Sorrell 2013). Older adults’ depression and anxiety worsen if they are oversensitive to life, have unstable moods, re-think their past mistakes, and even indulge in repetitively experiencing negative moods (Gou et al. 2013; Lou and Ng 2012; Painter et al. 2012).

The finding of this study might contribute to adjustment strategies of counseling and interventions of anxiety and depression for older adults, as researchers debate whether rumination may be considered a maladaptive or adaptive coping strategy. Older adults with high levels of neuroticism may benefit from modifying their cognitive style and giving up their thinking habit of rumination; as we found in this study, rumination accounts for a substantial and significant portion of the variance in symptoms of anxiety and depression. Attention-training or mindfulness-based CBT can be adopted to obtain cues to activate themselves that have been found to a long-term reduction on habit of rumination cognition, which particularly coincide with theory of CBT, and achieve protection of older adults from symptoms of anxiety and depression (Papageorgiou and Wells 2000). Mental health professionals may need to actively devote to changing the rumination of the elderly by adopting positive psychological intervention or therapies, such as CBT.

Certain limitations and unsolved concerns have been determined in this study, apart from some meaningful discoveries. First, proving the causal relationship among neuroticism, rumination, anxiety, and depression is infeasible as our study utilizes a questionnaire rather than an experiment. Furthermore, participants in this study are relatively young who may be with good health condition relatively; the Zung Scale may increase the apparent rates of depressive symptoms. Thus, the findings of the current study should be interpreted with caution. Second, we determined that whether older adults live by themselves significantly affects all psychological health indicators. Previous studies confirmed that loneliness is the core factor in older adults’ anxiety and depression (Barg et al. 2006). The companionship of family members or friends can largely improve the psychological health levels and living quality of elderly adults, thereby alleviating the influence of neuroticism and rumination on anxiety and depression. These moderating variables must be considered, and alternative pathways by which neuroticism may lead to symptoms of anxiety and depression should be identified in future studies. Different views exist on whether rumination is adaptive or maladaptive. Treynor et al. (2003) presented a two-factor model of rumination, namely, reflective pondering and brooding. The former is adaptive with its tendency to resolve problems related to cognition and can alleviate an individual’s depression symptoms, whereas the latter focuses on negative stimulus and indulges in negative emotion, which is a maladjusted response set. Future studies should explore the different effects of rumination dimensions on mental health and evaluate the relative contribution of different aspects of rumination in meditational analysis in older adults.

References

Barg, F. K., Huss-Ashmore, R., Wittink, M. N., Murray, G. F., Bogner, H. R., & Gallo, J. J. (2006). A mixed-methods approach to understanding loneliness and depression in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(6), S329–S339.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Black, J., & Reynolds, W. M. (2013). Examining the relationship of perfectionism, depression, and optimism: Testing for mediation and moderation. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 426–431.

Boyle, L. L., Lyness, J. M., Duberstein, P. R., Karuza, J., King, D. A., Messing, S., & Tu, X. (2010). Trait neuroticism, depression, and cognitive function in older primary care patients. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(4), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c2941b.

Cheung, F. M., & Leung, K. (1998). Indigenous personality measures Chinese examples. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(1), 233–248.

Chia, A.-L., & Graves, R. (2016). Examining anxiety and depression comorbidity among Chinese and European Canadian University students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115618025.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5.

Coyle, C. E., & Dugan, E. (2012). Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(8), 1346–1363.

Denburg, N., Weller, J., Yamada, T., Shivapour, D., Kaup, A., LaLoggia, A., et al. (2009a). Poor decision making among older adults is related to elevated levels of neuroticism. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37(2), 164–172.

Denburg, N. L., Weller, J. A., Yamada, T. H., Shivapour, D. M., Kaup, A. R., LaLoggia, A., et al. (2009b). Poor decision making among older adults is related to elevated levels of neuroticism. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9094-7.

Djernes, J. K. (2006). Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: A review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(5), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x.

Fiske, A., Wetherell, J. L., & Gatz, M. (2009). Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 363–389. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621.

Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(8), 1659–1669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009.

George, L. K. (2011). Social factors, depression, and aging. Handbook of aging and the. Social Sciences, 7, 149–162.

Gou, Y., Jiang, Y., Rui, L., Miao, D., & Peng, J. (2013). The nonfungibility of mental accounting: a revision. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(4), 625–633.

Griffith, J. W., Zinbarg, R. E., Craske, M. G., Mineka, S., Rose, R. D., Waters, A. M., & Sutton, J. M. (2010). Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychological Medicine, 40(07), 1125–1136.

Hansell, N., Wright, M., Medland, S., Davenport, T., Wray, N., Martin, N., & Hickie, I. (2012). Genetic co-morbidity between neuroticism, anxiety/depression and somatic distress in a population sample of adolescent and young adult twins. Psychological Medicine, 42(06), 1249–1260.

Harrington, J. A., & Blankenship, V. (2002). Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and Anxiety1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(3), 465–485.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420.

He, F., Guan, H., Kong, Y., Cao, R., & Peng, J. (2014). Some individual differences influencing the propensity to happiness: Insights from behavioral economics. Social Indicators Research, 119, 897–908.

Hirani, S. P., Beynon, M., Cartwright, M., Rixon, L., Doll, H., Henderson, C.,. .. Rogers, A. (2014). The effect of telecare on the quality of life and psychological well-being of elderly recipients of social care over a 12-month period: The whole systems demonstrator cluster randomised trial. Age and Ageing, 43(3), 334–341.

Hull, S. L., Kneebone, I. I., & Farquharson, L. (2013). Anxiety, depression, and fall-related psychological concerns in community-dwelling older people. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(12), 1287–1291.

Ingersoll-Dayton, B., Torges, C., & Krause, N. (2010). Unforgiveness, rumination, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 14(4), 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903483136.

Jiang, J., Tang, Z., Futatsuka, M., & Zhang, K. (2004). Exploring the influence of depressive symptoms on physical disability: A cohort study of elderly in Beijing, China. Quality of Life Research, 13(7), 1337–1346.

Jo, S. A., Park, M. H., Jo, I., Ryu, S. H., & Han, C. (2007). Usefulness of Beck depression inventory (BDI) in the Korean elderly population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(3), 218–223.

Kardum, I., & Krapić, N. (2001). Personality traits, stressful life events, and coping styles in early adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(3), 503–515.

Kendler, K. S., Gatz, M., Gardner, C. O., & Pedersen, N. L. (2006). Personality and major depression: A swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(10), 1113–1120. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1113.

Kendler, K. S., Gardner, C. O., Gatz, M., & Pedersen, N. L. (2007). The sources of co-morbidity between major depression and generalized anxiety disorder in a Swedish national twin sample. Psychological Medicine, 37(3), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291706009135.

Kocovski, N. L., Endler, N. S., Rector, N. A., & Flett, G. L. (2005). Ruminative coping and post-event processing in social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(8), 971–984.

Kong, T., He, Y., Auerbach, R. P., McWhinnie, C. M., & Xiao, J. (2014). Rumination and depression in Chinese university students: The mediating role of overgeneral autobiographical memory. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 221–224.

Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., & Cook, W. (2006). Rumination in adolescents at risk for depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 96(1), 39–47.

Leach, L. S., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A. J., Windsor, T. D., & Butterworth, P. (2008). Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: The role of psychosocial mediators. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 983–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0388-z.

Lou, V. W., & Ng, J. W. (2012). Chinese older adults’ resilience to the loneliness of living alone: A qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 16(8), 1039–1046.

Lyubomirsky, S., Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Nelson, S. K. (2015). Thinking about rumination: The scholarly contributions and intellectual legacy of Susan Nolen-Hoeksema. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 1–22.

Ma, X., Xiang, Y.-T., Li, S.-R., Xiang, Y.-Q., Guo, H.-L., Hou, Y.-Z.,. .. Tao, Y.-F. (2008). Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of depression in an elderly population living with family members in Beijing, China. Psychological Medicine, 38(12), 1723–1730.

McLaughlin, K. A., Aldao, A., Wisco, B. E., & Hilt, L. M. (2014). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor underlying transitions between internalizing symptoms and aggressive behavior in early adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 13–23.

Merema, M. R., Speelman, C. P., Foster, J. K., & Kaczmarek, E. A. (2013). Neuroticism (not depressive symptoms) predicts memory complaints in some community-dwelling older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(8), 729–736.

Mohlman, J., Bryant, C., Lenze, E. J., Stanley, M. A., Gum, A., Flint, A.,. .. Craske, M. G. (2012). Improving recognition of late life anxiety disorders in diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition: Observations and recommendations of the advisory committee to the lifespan disorders work group. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(6), 549–556. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2752.

Mor, N., & Winquist, J. (2002). Self-focused attention and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 638–662.

Muris, P., Roelofs, J., Rassin, E., Franken, I., & Mayer, B. (2005). Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(6), 1105–1111.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.100.4.569.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Jackson, B. (2001). Mediators of the gender difference in rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 37–47.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 92–104.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424.

Ormel, J., Jeronimus, B. F., Kotov, R., Riese, H., Bos, E. H., Hankin, B.,. .. Oldehinkel, A. J. (2013). Neuroticism and common mental disorders: Meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(5), 686–697.

Painter, J. A., Allison, L., Dhingra, P., Daughtery, J., Cogdill, K., & Trujillo, L. G. (2012). Fear of falling and its relationship with anxiety, depression, and activity engagement among community-dwelling older adults. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(2), 169–176.

Papadakis, A. A., Prince, R. P., Jones, N. P., & Strauman, T. J. (2006). Self-regulation, rumination, and vulnerability to depression in adolescent girls. Development and Psychopathology, 18(03), 815–829.

Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2000). Treatment of recurrent major depression with attention training. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 7(4), 407–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(00)80051-6.

Pasyugina, I., Koval, P., De Leersnyder, J., Mesquita, B., & Kuppens, P. (2015). Distinguishing between level and impact of rumination as predictors of depressive symptoms: An experience sampling study. Cognition and Emotion, 29(4), 736–746.

Peng, J., Jiang, Y., Miao, D., Li, R., & Xiao, W. (2013). Framing effects in medical situations: Distinctions of attribute, goal and risky choice frames. Journal of International Medical Research, 41(3), 771–776.

Peng, J., Xiao, W., Yang, Y., Wu, S., & Miao, D. (2014). The impact of trait anxiety on self-frame and decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27(1), 11–19.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Roelofs, J., Huibers, M., Peeters, F., Arntz, A., & van Os, J. (2008). Rumination and worrying as possible mediators in the relation between neuroticism and symptoms of depression and anxiety in clinically depressed individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(12), 1283–1289.

Santor, D.A., & Rosenbluth, M. (2005). Evaluating the contribution of personality factors to depressed mood in adolescents: conceptual and clinical issues. Depression and personality: Conceptual and clinical challenges, 22(1), 229–266.

Servaas, M. N., van der Velde, J., Costafreda, S. G., Horton, P., Ormel, J., Riese, H., & Aleman, A. (2013). Neuroticism and the brain: A quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies investigating emotion processing. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1518–1529.

Sorrell, J. M. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-5: Implications for older adults and their families. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 51(3), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20130207-01.

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), 199–228.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3), 247–259.

Vink, D., Aartsen, M. J., & Schoevers, R. A. (2008). Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: A review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 106(1), 29–44.

Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Castriotta, N., Lenze, E. J., Stanley, M. A., & Craske, M. G. (2010). Anxiety disorders in older adults: A comprehensive review. Depression and Anxiety, 27(2), 190–211.

Yohannes, A. M., Baldwin, R. C., & Connolly, M. J. (2000). Depression and anxiety in elderly outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Prevalence, and validation of the BASDEC screening questionnaire. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(12), 1090–1096.

Yu, X., Zhou, Z., Fan, G., Yu, Y., & Peng, J. (2016). Collective and individual self-esteem mediate the effect of self-Construals on subjective well-being of undergraduate students in China. s, 11, 209–219.

Zhang, Z., & Zhang, J. (2015). Belief in a just world mediates the relationship between institutional trust and life satisfaction among the elderly in China. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 164–169.

Zung, W. W., & Green, R. L. (1974). Seasonal variation of suicide and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 30(1), 89–91.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31160201), the National Social Science Foundation Education Program (Grant No. CEA130144), and National Social Science Fund (11BGL047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Xiaohui Chen declares that she has no conflict of interest. Jun Pu declares that he has no conflict of interest. Wendian Shi declares that he has no conflict of interest. Yangen Zhou declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Pu, J., Shi, W. et al. The Impact of Neuroticism on Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Elderly Adults: the Mediating Role of Rumination. Curr Psychol 39, 42–50 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9740-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9740-3