Abstract

Various studies have verified the detrimental effects of rumination as a maintenance factor for depressive symptoms (Spasojević et al. in: Papageorgiou, Wells (eds) Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment. Wiley, Hoboken, 2004). Much less is known about the dynamics of rumination as an outcome of powerful stressors that trigger negative thoughts and affect (Lyubomirsky et al. in Ann Rev Clin Psychol 11:1–22, 2015). The study contributes to the literature by investigating rumination among non-clinical, adult participants, using data from a convenience sample of white-collar employees from the US and Turkey (N = 383). We tested the mediational role of rumination in the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being, controlling for the potential moderational effect from self-efficacy. In support of our hypotheses, the results reveal that people who are less satisfied with their job tend to ruminate more and, therefore, they feel less satisfied and less happy. The expected moderation effect of self-efficacy could not be supported by the data in our study. Our findings suggest that employees may find it difficult to offset rumination resulting from having low job satisfaction, even when they possess high self-efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Philosophers and scientists have strived, for centuries, to comprehend the elements of a happy, satisfied life, a central question which has gained revived popularity in academic and policy circles in recent decades (Helliwell and Barrington‐Leigh 2010). Following the appearance of the article by Diener (1984), over one thousand studies have been published under the heading of subjective well-being (SWB for short) (Busseri and Sadava 2011). In modern psychology and medicine, research on SWB primarily focuses on potential outcomes of positive mental states on psychological and physical health. Past studies showed that differences in cognitive responses to life events are largely responsible for differences in levels of individual well-being (Lyubomirsky 2001). Unhappy people are more likely to make unhealthy social comparisons with others’ successes or failures, more likely to perceive, frame, and recall life circumstances in negative ways, and more likely to have a pessimistic view of future possibilities. Rumination is another aspect of these psychologically detrimental cognitive responses and it has captured the attention of researchers (Papageorgiou and Wells 2004). The ruminative response style is conceived as a pattern of thoughts that focus the individual’s attention to his or her distress, suppress any actions that might distract the individual from his or her psychological state, and inhibit problem solving (Lakdawalla et al. 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema 1991).

Since Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) originally proposed the concept of rumination, various studies have been conducted, especially among adolescents (see Abela and Hankin 2007; Lakdawalla et al. 2007, for reviews). Past studies indicated that rumination is related to critical components of psychological health such as depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and pessimism (Ciesla and Roberts 2007; Hankin 2008; Moberly and Watkins 2008; Spasojević et al. 2004). The relationship between rumination and well-being is such that it operates almost as a vicious cycle. People who daily ruminate feel less happy (Newman and Nezlek 2017), and happier people are less vulnerable to rumination after a stressful event (Zanon et al. 2016). Another issue that concerns researchers regarding rumination is its different constituents. Usually, a distinction is made between reflection and brooding. It was revealed, among adolescents, that brooding might be more critical for psychological health than reflection or a broad measurement of rumination (Arnarson et al. 2016; Burwell and Shirk 2007). In a longitudinal study with Finnish employees in health services, it was revealed that emotionally laden repetitive thoughts present during non-work time led to sleep disorders and posed a risk factor for poor health over time (Kinnunen et al. 2017). Problem-solving rumination, on the other hand, are shown to have positive effects via recovery and increased work engagement (Hamesch et al. 2014).

In this study, we focus on the relationship between job satisfaction and well-being, utilizing subjective happiness and life satisfaction measures simultaneously, and tackle the mediational role of rumination in this relationship. We should point out that rumination has rarely been investigated outside cases of depression or trauma and that our study is among a few studies that use a nonclinical sample. We also investigate the potential moderational effect of self-efficacy, a major psychological variable of personal control that has been shown to relate to various positive outcomes for individuals (Bandura 1977). In the following paragraphs, we outline the interrelationships among the study variables, present the hypotheses, and describe our model.

1 Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being refers to how one experiences and evaluates the quality of his or her life (Diener 1984, 2000). It relates to stronger interpersonal relations, mental health, and more self-enhancing cognitive styles (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005). It is a multi-faceted construct with two main components: the affective component encompasses emotions associated with reactions to life events and experiences (subjective happiness), and the cognitive component refers to judgments and evaluations of one’s satisfaction with life (life satisfaction). Affective and cognitive components are moderately correlated in most societies (Diener 2000), but they are still distinct from each other at the individual level. That is to say, a person’s cognitive assessment of his or her life satisfaction does not have to be directly related to the frequency of positive emotions the person experiences. For example, a person with low income may lack positive feelings but may still express relatively higher contentment and satisfaction, thanks to thinking styles fostered by some cultural teachings or comparisons with others under worse conditions. Or in cases such as giving birth to a child when people feel better in emotional terms, they may still evaluate their lives as worse than before because they have less quality time to themselves or with their spouses (see Luhmann et al. 2012, for a general review of the effects of life events).

At the individual level, SWB is determined by three major factors: a set point for happiness deriving from genetically-determined personality characteristics, circumstantial factors, and happiness-relevant activities and practices (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005). Among various personality characteristics, neuroticism is the strongest predictor of (diminished) life satisfaction and happiness (DeNeve and Cooper 1998). Critical events in life (such as divorce and unemployment) have negative impact on both affective and cognitive well-being, showing relatively more detrimental outcomes for the cognitive component (Luhmann et al. 2012). It should be acknowledged that personality is difficult to change, and circumstances sometimes occur beyond our control. Persons can, however, choose from different activities and practices to alter their thoughts and to reverse negative effects on SWB. It was shown, for example, that males engaged in leisure activities such as physical training whereas females maintained and developed positive social relationships to overcome negative effects from life events (Tkach and Lyubomirsky 2006). Persons can also develop ways to increase their overall SWB by showing gratitude or by reframing situations in a more positive light (Emmons and McCullough 2003) and by striving for important future goals (Sheldon and Houser-Marko 2001).

2 SWB and Job Satisfaction

Work conditions have a powerful influence on subjective well-being (Stansfeld et al. 2013).The present study focuses on one of the most important psycho-social characteristics of work, job satisfaction which is defined as a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experience (Luthans 2005). It is basically how happy an employee is with a job (Hackman and Oldham 1980). Job satisfaction is one of the most studied organizational factors because it impacts key work outcomes such as performance, burnout, turnover, and absenteeism (Badran and Kafafy 2008). It is also considered a barometer of employee perceptions of organizational fairness (Brooke et al. 1988).

We argue that individuals who are satisfied with their job tend to be happy and satisfied with their lives. Thus, individuals’ SWB is not merely a function of dispositions; it is determined to a significant extent by the level of their job satisfaction. Past research consistently showed that job satisfaction is related to life satisfaction (Judge and Watanabe 1993; Van de Vliert and Janssen 2002). In a meta-analytic review, Tait et al. (1989) have found this average correlation to be .44. One explanation is that job satisfaction influences other aspects of an individual’s life. For example, a person experiencing job satisfaction is happier, and the happiness manifests itself in other aspects of life, thereby leading to life satisfaction (Wright et al. 1999).

Job dissatisfaction, on the other hand, is a stressor that reduces both subjective happiness and life satisfaction, the two main components of SWB. Our theoretical framework for this argument comes from stress research. Sometimes stress components (stressors and strains) are not stable, but instead change slowly in time. According to the stressor-strain trend model (Frese and Zapf 1988; Garst et al. 2000), the trends of stressors and strain are related, and there are various ways in which long-term exposure to stressors may lead to psychological and psychosomatic dysfunction in the course of time (Garst et al. 2000). Nesselroade (1991) called this an “incubation time” when stressors show effect gradually. For example, gradual increases in job demand, time pressure, financial limitations etc. at work lead employees to enter an “incubation time” during which job satisfaction gradually reduces. After this incubation time, employees who suffer from lack of job satisfaction finally break the threshold point, and start showing or experiencing rather long-term effects such as chronic unhappiness (Frese and Okonek 1984). Accordingly, we hypothesized that job satisfaction is positively linked to subjective happiness (H1a), and to life satisfaction (H1b) (See Fig. 1).

3 Rumination as a Mediator

Rumination is defined as preservative self-focus that is recursive and persistent (Spasojević et al. 2004). It has been investigated as a component of a general negative cognitive style or treated as a vulnerability factor. Past research showed that rumination was associated with poor well-being, depression, hopelessness, pessimism, negative affect, self-criticism, low mastery, dependency, and neuroticism (Ciesla and Roberts 2007; Moberly and Watkins 2008; Spasojević et al. 2004). Newman and Nezlek (2017) found that daily rumination was negatively associated with daily well-being. People who ruminate tend to engage more in negative thoughts and memories (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008) and, therefore, they become more susceptible to poor well-being.

The negative relationship between rumination and well-being was explained by the discrepancy between how people think they should feel and how they actually feel. According to McGuirk et al. (2017), there are constant reinforcements and social expectations that remind the value of happiness. When negative events or outcomes happen, feelings of happiness are interrupted. This interruption leads to a discrepancy between the social pressure to feel happy and one’s lack of happiness (McGuirk et al. 2017). Rumination may result in facing such discrepancies that lead to negative self-reflection, and to focusing repetitively on the possible causes and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008).

Although rarely, rumination has also been investigated as an outcome of powerful stressors which trigger negative thoughts and affect (Lyubomirsky et al. 2015). It was shown that students who ruminated more after an earthquake showed increased levels of depression in a follow-up, controlling for their habitual rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991). Later, Robinson and Alloy (2003) employed several measures to differentiate trait-like rumination from rumination-as-response to life stress. It was shown that stress-reactive rumination was a powerful predictor of the onset and duration of depressive episodes, after controlling for inclination towards ruminative thinking among participants. In a similar vein, Michl et al. (2013) revealed in their longitudinal study that level of rumination increased following stressful events, which also was found to mediate the relationship between stress and anxiety in a 7-month follow-up. In conclusion, available evidence, although limited in numbers yet, is satisfactory to justify further examinations into rumination-as-response to life events and stress.

In this study, we look at the consequences of rumination for subjective well-being, as a response to stress associated with low job satisfaction. Following Spasojević et al. (2004), stress associated with low job satisfaction can be conceptualized as the discrepancy between one’s current and desired state at work (or in professional life in general). Employees may sometimes develop successful strategies to cope with this kind of anxiety, by revising their goals and creating alternative opportunities, or by distracting themselves with different activities. However, finding a resolution may be difficult for most. Furthermore, employees may find it difficult to disengage attention from the perceived problem. When there is no satisfactory resolution to a felt discrepancy, employees who are not satisfied at work are likely to start ruminating. Excessive dwelling is associated with outcomes such as undesirable cognitive interference, mainly because chronic self-examination consumes valuable cognitive resources and harms concentration (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). Furthermore, failure at finding a resolution may increase feelings of helplessness, creating a vicious circle that augments rumination.

We predict that rumination leads to subjective unhappiness and diminished satisfaction with life due to several mechanisms. It has been verified that rumination leads to negative, biased interpretation of events and that persons high on rumination tend to alienate themselves from their interpersonal environment and reduce willingness to engage in pleasant activities (Ciesla and Roberts 2007). Conversely, stressors’ impact is minimal for employees who are satisfied with their jobs. Consequently, they are more apprehensive about the positive aspects of their job, less prone to ruminate, and conserve their cognitive capacity constructively (Haar et al. 2014; Rothbard 2001). Thus, job satisfaction’s impact on SWB is mainly due to employees’ ability to focus on positive and constructive thoughts instead of ruminating. Accordingly, we hypothesized that the relationship between job satisfaction and SWB will be mediated by rumination such that employees who are satisfied with their job ruminate less, and thereby, exhibit more positive subjective happiness (H2a), and more life satisfaction (H2b) (See Fig. 1).

4 The Moderational Mediation: The Role of Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1995) stated that exercising control over events that affect one’s life increases the person’s chances of adaptability and development. By regulating their own thoughts, motivation, and feelings, persons may develop better coping capabilities and better respond to stress and depression they experience under difficult situations. Self-efficacy, which is defined as a person’s estimate of one’s fundamental ability to cope, perform, and be successful (Bandura 1977, 1997), is one of the core elements of this inner psychological mechanism. Individual differences in this system of beliefs are associated with differences in feelings of preparedness as well as control and thus influence various psychological outcomes. It has been shown that self-efficacy correlates with belief in free will (Crescioni et al. 2016) and future planning (Azizli et al. 2015) which, in turn, determine outcomes such as life satisfaction.

Self-esteem, locus of control, neuroticism, and self-efficacy may be markers of the same higher order concept (Judge et al. 2002). This line of argument suggests that self-efficacy is determined by an intricate interplay between stable characteristics, personal experiences, and changes in cognitive states. As proof of the link between stable factors and self-evaluations, it was shown that the negative effect of neuroticism on subjective happiness was mediated by self-efficacy (Strobel et al. 2011).

In our conceptual model, self-efficacy was expected to moderate the mediation of rumination. Low self-efficacy is associated with feelings of anxiety and helplessness, and leads to rumination and negative anticipatory thoughts about the future (Bandura 1997). Employees with low self-efficacy are doubly jeopardized due to the way they perceive their work environment and construe work outcomes. Low perceptions of self-efficacy are associated with negative appraisal of individual worthiness (Jaensch et al. 2015), negative anticipatory thoughts about the future, and rumination (Bandura 1997). On the other hand, individuals with high self-efficacy have higher expectations that they will succeed, therefore they are more persistent in tasks despite setbacks (Judge and Bono 2001). They tend to possess more optimistic judgments regarding their jobs and are less adversely affected by job dissatisfaction. They also show more personal initiative (Speier and Frese 1997) and take charge more often (Morrison and Phelps 1999). Therefore, when faced with work problems and challenges, they exhibit resilience, and take action, rather than ruminate (Luthans et al. 2007). Consequently, the mediational role of rumination should be weakened, and differences in SWB will be less consequential in the case of high self-efficacy. This leads us to our final hypothesis that self-efficacy moderates the mediational role of rumination on subjective happiness and life satisfaction, such that each one of these mediated relationships is weaker for employees who have high self-efficacy (H3).

5 Method

5.1 Participants

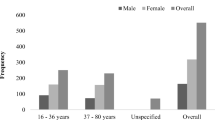

A total of 627 participants started the online questionnaire, but only 383 participants completed it (134 from USA, 249 from Turkey) (completion rate of 61%). Females comprised 71% of the US sample and nearly 68% of the Turkish sample. Mean age was 37.27 (SD = 9.33) for the Turkish sample and 38.03 (SD = 11.06) for the US sample. Participants are white-collar professionals in paid or self-employed work.

5.2 Procedure

Data were collected using the online version of the survey in March 2015. Authors distributed, via email, an announcement to their networks explaining the goals of the project and the web link to the survey. Survey questions were delivered in English in the US, and in Turkish in Turkey. All potential respondents were informed that participation was voluntary, the responses would remain confidential, and no gifts or rewards would be given.

6 Materials

The measures are derived from the literature. Rumination was measured using the 22-item Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) that was developed by Treynor et al. (2003). The measure has an internal reliability of .85. In its current application, the 12 depression-related items in RRS are sometimes discarded from use. The remaining items, which compose the short version of RRS, measure two aspects of rumination, reflection and brooding. Reliabilities of the long and short versions in Turkish were found to range between .72 and .86 (Erdur-Baker and Bugay 2010, 2012). Since reflection is a healthy response to problems among nonclinical adults (Whitmer and Gotlib 2011), only scores for the brooding subscale were used in the analyses. The reliability of the brooding subscale in Turkish is .75 (Erdur-Baker and Bugay 2012). A sample question for brooding is “Why do I have problems other people don’t have?”

Subjective happiness was measured using a 4-item measure of global subjective happiness developed by Lyubomirsky and Lepper (1999). It was tested with American and Russian college students and older adults, and showed high internal consistency between .79 and .94 for different subsamples. Reliability statistics for the Turkish sample ranges from .65 to .70 (Dogan and Totan 2013). A sample question is “Some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you?”

Life satisfaction was measured using the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al. 1985). This scale measures global life satisfaction, an individual’s evaluation of his or her life in general. A sample question is “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.” A meta-analysis has revealed that the mean Cronbach’s alpha for SWLS across samples was .78 (Vassar 2008). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the scale were confirmed recently in a study by Durak et al. (2010) in which reliability of SWLS was found to be .81.

Job satisfaction was measured using the 5-item version of the Brayfield and Rothe (1951) Index of Job Satisfaction, which measures overall job satisfaction. A sample question is “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work.” The reliability of the measure is .88 (Judge et al. 1998). Internal reliability of the Turkish version of the scale ranges between .78 and .83 (Buyukgoze-Kavas et al. 2013). Note that two of the five items of job satisfaction had to be reversed, so that all items had higher numbers indicating higher values.

General self-efficacy was measured using English and Turkish versions of the 10-item scale that was developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995). German version developed in 1979 by the authors were later revised and adapted to other languages by various co-authors (General Self-Efficacy Scale 2012). In samples from 23 nations, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .76 to .90, with the majority in the high .80 s. A sample question is “I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort.”

7 Data Analytic Approach

The analyses involved five steps. First, the items for each of the five scales (job satisfaction, self-efficacy, rumination, life satisfaction, and subjective happiness) were averaged into a dimensionless composite score. Second, those composite scores were screened for normality and univariate and multivariate outliers, with appropriate transformations performed to make the data more suitable for analyses. Third, to aid interpretability, the dimensionless variables were further transformed into t scores (M = 50, SD = 10). Fourth, cross-sectional analyses were conducted to determine differences in responses between the US and Turkey. Finally, a structural model was developed with SPSS AMOS 23 to test hypotheses 1–3. Significance of the total, direct, and indirect effects was conducted with bootstrap approximation obtained by constructing two-sided bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals.

8 Results

Prior to analyses, all variables were screened for normality and outliers, following the recommendations of Tabachnick and Fidell (2013). There was one univariate outlier for self-efficacy (z = − 5.14, p < .001). That score was substituted with the next lowest score (z = − 3.06, p > .001). No other univariate outliers or multivariate outliers were found. All variables had skewness that was statistically different from zero (z > 3.29, p < .001). Thus, job satisfaction, self-efficacy, subjective happiness, and life satisfaction were reversed and log transformed, and rumination was log transformed. To aid interpretability, the log transformed variables were further transformed into t scores, with higher numbers indicating higher values. An interaction term was created with the centered product of the t scores of job satisfaction and self-efficacy.

Mean composite scores for job satisfaction, self-efficacy, rumination, life satisfaction, and subjective happiness are reported in Table 1. Also shown in Table 1 are skewness and kurtosis for the five composite scores, and their correlations. Note that descriptive statistics are for the untransformed variables, whereas all analyses were conducted with the transformed variables.

The correlations between job satisfaction and subjective happiness and between job satisfaction and life satisfaction were .40 and .40, respectively, both statistically significant at p < .001. Thus, there was support for hypotheses H1a and H1b.

If rumination mediates the relationship between job satisfaction and SWB, the indirect effect of job satisfaction on SWB through rumination (a1b in Fig. 1) should be different from zero. That was, in fact, what was found (a1b = .12, 95% CI = .68 to 0.17, p = .001), lending general support for H2. Both the indirect effect of job satisfaction on life satisfaction through rumination and SWB (a1be = .38, 95% CI = .27–.48, p = .001) and the indirect effect of job satisfaction on subjective happiness through rumination and SWB (a1bd = .41, 95% CI = .32–.50, p = .001) were statistically significant, lending specific support for H2a and H2b, respectively.

For H3 to be supported, and thus have self-efficacy moderate the indirect effect of job satisfaction on SWB through rumination, the indirect effect a3b shown in Fig. 1 would have to be different from zero (Hayes 2015). This was not what was found (a3b = − .07, 95% CI = − .40–.17, p = .548). Thus, H3 was not supported by the data.

Since the participants are from two different countries, we additionally checked for potential differences between the two samples. The differences between Turkey and the US are shown in Table 2. Turkish participants engaged in more rumination (t = − 5.20, p = .000, Cohen’s d = .57) and reported lower life satisfaction (t = 3.04, p = .003, Cohen’s d = .32) and lower self-efficacy (t = 2.43, p = .013, Cohen’s d = .27) than American participants. No differences between American and Turkish participants were found in job satisfaction (t = 1.74, p = .084) and subjective happiness (t = 1.32, p = .189).

9 Conclusion and Discussion

Job satisfaction has a profound effect on subjective evaluations of well-being. Our results showed that people who are satisfied with their job report stronger subjective happiness and life satisfaction. More importantly, as expected, we found that those with low job satisfaction tend to ruminate more and, thus, show less subjective happiness and life satisfaction. Organizations are responsible for safeguarding person-job fit and providing the right work environment for their employees. When these conditions are not provided, unit managers and employees should be aware and concerned about detrimental effects of rumination. It has been shown in lab experiments that rumination may affect stress reactivity whether or not the person is currently depressed (Woody et al. 2015).

Rumination is detrimental to the individual not only because it depletes psychological resources but also because it may exhaust physical vitality. Studies have shown that rumination is a strong predictor of acute and chronic work-related fatigue (Querstret and Cropley 2012) and self-defeating behaviors such as heavy alcohol use (Frone 2015). Rumination may have some other direct and indirect consequences for an organization’s work processes. Madrid et al. (2015) have shown that employees high in rumination have a greater tendency to withhold information and ideas at work, as they consume psychological resources needed for participating in social interaction with others at work. Since idea generation is an important precursor to creativity and innovation (Heslin 2009), rumination at work may hinder an organization’s learning capabilities.

It has been shown earlier that core self-evaluations, including self-efficacy, are important factors in the job-life satisfaction relationship (Heller et al. 2002). The expected moderation effect of self-efficacy, however, could not be supported by the data in our study. One explanation for this outcome is that employees may find it difficult to offset rumination resulting from having low job satisfaction, even when they possess high self-efficacy. When physical and psychological distractions are present in a work environment, impact of self-efficacy may diminish as a consequence of intensification of stress among employees. Contextual influences and performance outcomes that hinder self-efficacy are likely to influence the job-life satisfaction relationship since this is also determined both by dispositional and environmental factors. Hence, it may not be adequate only to look at individuals’ self-efficacy. Factors such as conflict with co-workers, which have been shown to increase depressive symptoms (Frone 2000), may be tackled in future studies to better grasp the role of factors outside the person’s immediate control.

9.1 Practical Implications

Papageorgiou and Wells (2004) have reviewed results from a series of psychological and cognitive treatments for depressive rumination. They observe that people wrongly hold a positive view of rumination on the account of the belief that rumination is helpful for solving problems, for gaining insight, and preventing future mistakes. Findings reveal also that the opposite alternative, that is suppression of depression-related thoughts, appears to be somewhat successful in the short term but these efforts may be highly detrimental when negative thoughts rebound later. These findings imply that there is no palpable way out of the negative effects of rumination. Nevertheless, we suggest that employees who tend to ruminate may be approached with specific methods to help them overcome ruminative thinking stemming from low satisfaction with work.

A study by Thomsen et al. (2011) suggest that highly ruminating individuals dwell longer on negative events and memories and that they perceive the likelihood of future positive events to be weaker compared to potential negative ones. In our opinion, employees who show low levels of job satisfaction, unless they can find better jobs, may benefit from keeping a diary of positive events and emotions at work, to redirect attention from negative thoughts or, at least, to attenuate effects from them. In addition, consultants, colleagues or even friends may ask employees with negative experiences at work to visualize having a good, satisfying job in the near future, by helping them focus on their strengths and capabilities. It is also important that employees engage in activities that they like in their leisure time after work to distract ruminative thoughts and to increase personal sense of control (Cropley and Millward Purvis 2003). In more critical cases of depressive rumination, it is recommended that the person is asked to monitor his or her activities on an hourly basis and to rate the degree of mastery and pleasure for each of the activities (Purdon 2004). This is intended to facilitate discussion of thoughts, such as ‘‘I never do anything,’’ and ‘‘everything is a chore.’’

It has been suggested that individuals can facilitate adaptive self-reflection by self-distancing (Kross and Ayduk 2011). Self-distancing is a mechanism whereby the person adapts an outsiders’ perspective instead of recounting the past events in a self-immersed manner. It is hypothesized that such self-distancing allows people to focus on the broader context in order to reconstrue the negative experiences from a new perspective and helps them attenuate the undesirable effects from self-focused reflection. In their study with Russians and Americans, Grossmann and Kross (2010) have discussed rumination in the context of individualism-collectivism and argued that individuals from collectivistic societies may find it easier to self-distance. However, such evidence for differences in adaptive self-reflection is embryonic. It is also not clear how self-distancing works for complex outcomes such as job dissatisfaction.

In addition to evident symptoms of rumination, such as dwelling on negative aspects of events and exaggerating the probability of negative outcomes, we argue that rumination may get disguised under certain biases and errors in thinking (Papageorgiou and Wells 2004). One critical bias, for example, is dichotomous thinking, which is thinking in all-or-nothing terms. The problem with dichotomous thinking is that it inflates the emotions of the person and, thus, may lead to rumination due to anxiety, helplessness or feelings of disappointment. We may even argue that, when this kind of thinking becomes pervasive in a company, it will have an indirect effect on the employees and augment their likelihood of rumination, by polarizing groups or teams involved in coordinated tasks. Another bias that needs attention is the negativity effect, a common bias resulting from asymmetry in the way humans interpret positive versus negative information. Negative events require more attention, elicit more causal attribution than positive events and are perceived as more complex (Rozin and Royzman 2001). Generally, information with negative nature (e.g. unpleasant social interactions, lowered job satisfaction) have a greater effect on one’s psychological state and processes than do neutral or positive ones. We believe that managers and employees need to be aware of these likely systematic biases and errors in their and others’ thinking to stop rumination from aggravating. Asking the HR department of the company to develop cases for study, employees can then be requested to complete short training programs, preferably with the help of experts. Such rudimentary programs must be designed to help employees avoid attributional errors in their personal and work lives and to help them develop better decision-making skills. It has been shown that attending a 1-day workshop based on cognitive behavior therapy helped employees have less chronic fatigue and less affective rumination at follow-up in six-months, compared to individuals who did not attend the workshop (Querstret et al. 2016).

We, of course, do not want to deemphasize the fact that legal and ethical responsibility lies with the employers to ensure that working conditions are right for all employees, before a need arises to correct problems associated with low satisfaction and rumination. We believe, however, that people in work life should be aware of threats from poor working conditions and thus be able to develop better coping strategies in face of hardship, until their situation improves or new, better job opportunities arise.

9.2 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

In this study, we investigated the relationship between job satisfaction and two components of SWB (subjective happiness and life satisfaction) using data from Turkey and the US. Although the hypotheses were verified, except for self-efficacy, the study could have benefited from a more detailed, multidimensional measurement of job satisfaction to cover factors such as autonomy, job demands, and work-life balance. Another limitation is the likely common method bias resulting from use of self-report measures. Future studies may benefit from supplementing measures of rumination and self-efficacy with observer ratings. It is also important to note that mediational analyses do not provide the best evidence for causal relationships because they are unduly influenced by the relationships between the mediator variable and the dependent variable to the exogenous variable (Lindenberger and Potter 1998). The model presented in this paper, therefore, should be interpreted with caution.

Although we did not detect a strong moderator effect for self-efficacy, we believe that there is merit to retesting this hypothesis in future studies. As individuals move up the income distribution scale, the association between job and life satisfaction becomes stronger (Georgellis and Lange 2012). Our findings regarding self-efficacy may have been limited since our sample is composed of white-collar jobholders in relatively high-paying positions. Extensive analyses of data from over twenty countries verify that self-efficacy is a universal construct (Scholz et al. 2002; Vieluf et al. 2013). There is, however, evidence that individuals in highly collectivistic, especially Asian, societies tend to report lower self-efficacy (Scholz et al. 2002). Furthermore, the meta-analysis by Avey et al. (2011) has revealed that positive effects of psychological capital variables, including self-efficacy, on desirable work attitudes and behaviors were stronger in US sample versus non-US samples. The expected effects from self-efficacy are likely to emerge in studies that employ more than two samples and a larger variety of cultural differences.

A related but different factor that needs to be considered in the work setting is collective self-efficacy, which can be defined as the extent to which people believe that they can self-regulate collectively to achieve work goals (Maddux and Volkmann 2010). Since no worker can achieve complex work goals individually, collective self-efficacy may be investigated for its effects on job satisfaction and rumination. Finally, future studies may take into consideration testing of alternative models that include intolerance for uncertainty, a factor which has been shown to be associated with depression (de Jong-Meyer et al. 2009; Sexton and Dugas 2009; Yook et al. 2010).

Dispositional traits such as neuroticism, which we did not intend to measure in this study, are potent determinants of the variables in the model, especially job satisfaction (see Judge et al. 2002), and, indirectly, the results from these variables. There is, however, evidence that positive work experiences have the potential to modify basic personality dispositions such as negative emotionality (Roberts et al. 2003). This suggest that determinism associated with personality traits may be approached with some caution, despite obvious merits with this perspective. We also believe that suggestions for interventions to contest rumination, which is our main concern in this study, are likely to be the same, whether the problem stems from dispositions or experiences (or from poor selection versus poor management from an organizational point of view). One key concept here is mindfulness, which promotes positive receptivity and involves being non-evaluative and non-defensive in processing information about one’s experiences (Brown et al. 2007). Since negative emotional reactivity associated with neuroticism is partially due to low levels of mindfulness (Wenzel et al. 2015), increasing mindfulness among employees may operate as a buffer against cognitive weaknesses from dispositions. Mindfulness is also likely to help employees with poor work experiences. It was shown in an internet-based intervention, for example, that mindfulness training promoted occupational health and lowered rumination (Querstret et al. 2017).

It has been argued that rumination may be a more complex process than originally suggested, consisting of both adaptive and maladaptive components (Vassilopoulos and Watkins 2009). Differences between these components may be related to cultural variation in implicit theories about life (e.g., “life is good” versus “good and bad things happen in life”) which largely determine retrospective judgments of well-being (Oishi 2002). Retrospective judgments are thought to be as important as actual emotional experiences, and these orientations comprise certain implications for rumination. A common strategy for well-being in most Western cultures is distancing oneself psychologically from negative experiences. In contrast, in some non-Western cultural traditions, well-being is defined as a dialectical interaction of positive and negative experiences, and people may prefer working through negative experiences through positive reappraisal. Tsai et al. (2011) has compared European American and Asian American students and revealed that presence of elevated levels of rumination and depressive symptoms in Asian Americans were not associated with lower levels of happiness in their lives. Grossman et al. (2014), on the other hand, have revealed that a group of Japanese participants reported significantly higher trait-level brooding but also that they viewed these experiences more favorably than their American counterparts. These potential differences imply that there may be significant cultural differences in terms of vigilance against outcomes from rumination associated with negative experiences. These findings partly confirm earlier studies which revealed that negative emotions had more negative impact on life satisfaction in individualistic nations, in comparison to collectivistic nations (Kuppens et al. 2008). Future studies should be developed to better understand these potential cross-cultural differences and the role of nonjudgmental self-focus in subjective well-being.

Finally, another question for exploration is co-rumination, which has been found to have a differential effect on male versus female workers’ stress levels (Haggard et al. 2011). Findings reveal that, when male workers are experiencing low levels of stress, co-rumination is likely to make them distressed about problems that typically would not upset them. In opposition, it is found that co-rumination is detrimental for women when their job stress levels are high. On the other hand, for males, it is found that co-rumination is related to satisfaction with their friend with whom they co-ruminate. However, since this relationship benefit might reinforce a co-ruminative style, co-rumination tends to be extremely maladaptive for male workers with low job stress. Further studies are needed to explore these gender differences and the interactive dynamics of rumination in the workplace.

References

Abela, J. R., & Hankin, B. L. (2007). Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents. In J. R. Z. Abela & B. L. Hankin (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents (pp. 35–78). New York: Guilford Press.

Arnarson, E. Ö., Matos, A. P., Salvador, C., Ribeiro, C., de Sousa, B., & Craighead, W. E. (2016). Longitudinal study of life events, well-being, emotional regulation and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,38(2), 159–171.

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly,22(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20070.

Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., & Giammarco, E. A. (2015). Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences,82, 58–60.

Badran, M., & Kafafy, J. (2008). The effect of job redesign on job satisfaction, resilience, commitment and flexibility: The case of an Egyptian public sector bank. International Journal of Business Research, 8(3), 1–18.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/rev/84/2/191/.

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of self-control. Gordonsville, VA: WH Freeman & Co.

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology,35(5), 307–311.

Brooke, P. P., Russell, D. W., & Price, J. L. (1988). Discriminant validation of measures of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology,73(2), 139–145.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry,18(4), 211–237.

Burwell, R. A., & Shirk, S. R. (2007). Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: Associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology,36(1), 56–65.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review,15(3), 290–314.

Buyukgoze-Kavas, A., Duffy, R. D., Güneri, O. Y., & Autin, K. L. (2013). Job satisfaction among Turkish teachers: Exploring differences by school level. Journal of Career Assessment,22(2), 261–273.

Ciesla, J. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2007). Rumination, negative cognition, and their interactive effects on depressed mood. Emotion,7(3), 555–565.

Crescioni, A. W., Baumeister, R. F., Ainsworth, S. E., Ent, M., & Lambert, N. M. (2016). Subjective correlates and consequences of belief in free will. Philosophical Psychology,29(1), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2014.996285.

Cropley, M., & Millward Purvis, L. (2003). Job strain and rumination about work issues during leisure time: A diary study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,12(3), 195–207.

de Jong-Meyer, R., Beck, B., & Riede, K. (2009). Relationships between rumination, worry, intolerance of uncertainty and metacognitive beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences,46(4), 547–551.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin,124(2), 197–229.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin,95(3), 542–575.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist,55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.34.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment,49(1), 71–75.

Dogan, T., & Totan, T. (2013). Psychometric properties of Turkish version of the subjective happiness scale. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being,1(1), 21–28.

Durak, M., Senol-Durak, E., & Gencoz, T. (2010). Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale among Turkish university students, correctional officers, and elderly adults. Social Indicators Research,99(3), 413–429.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,84(2), 377–389.

Erdur-Baker, O., & Bugay, A. (2010). The short version of the Ruminative Response Scale: Reliability, validity and its relation to psychological symptoms. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,5, 2178–2181.

Erdur-Baker, O., & Bugay, A. (2012). The Turkish version of the Ruminative Response Scale: An examination of its reliability and validity. The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment,10(2), 1–16.

Frese, M., & Okonek, K. (1984). Reasons to leave shiftwork and psychological and psychosomatic complaints of former shiftworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology,69(3), 509–514.

Frese, M., & Zapf, D. (1988). Methodological issues in the study of work stress: Objective vs. subjective measurement of work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In C. L. Cooper & R. Payne (Eds.), Causes, coping and consequences of stress at work (pp. 375–411). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Frone, M. R. (2000). Interpersonal conflict at work and psychological outcomes: Testing a model among young workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,5(2), 246–255.

Frone, M. R. (2015). Relations of negative and positive work experiences to employee alcohol use: Testing the intervening role of negative and positive work rumination. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,20(2), 148–160.

Garst, H., Frese, M., & Molenaar, P. (2000). The temporal factor of change in stressor-strain relationships: A growth curve model on a longitudinal study in East Germany. Journal of Applied Psychology,85(3), 417–438. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.85.3.417.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (2012). Retrieved January 21, 2015 from http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/selfscal.htm.

Georgellis, Y., & Lange, T. (2012). Traditional versus secular values and the job–life satisfaction relationship across Europe. British Journal of Management,23(4), 437–454.

Grossmann, I., Karasawa, M., Kan, C., & Kitayama, S. (2014). A cultural perspective on emotional experiences across the life span. Emotion,14(4), 679–692.

Grossmann, I., & Kross, E. (2010). The impact of culture on adaptive versus maladaptive self-reflection. Psychological Science,21(8), 1150–1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376655.

Haar, J. M., Russo, M., Suñe, A., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2014). Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior,85(3), 361–373.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work Redesign. Reading, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley.

Haggard, D. L., Robert, C., & Rose, A. J. (2011). Co-rumination in the workplace: Adjustment trade-offs for men and women who engage in excessive discussions of workplace problems. Journal of Business and Psychology,26(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9169-2.

Hamesch, U., Cropley, M., & Lang, J. (2014). Emotional versus cognitive rumination: Are they differentially affecting long-term psychological health? The impact of stressors and personality in dental students. Stress and Health,30(3), 222–231.

Hankin, B. L. (2008). Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: A short-term prospective multiwave study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,117(2), 324–333.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research,50(1), 1–22.

Heller, D., Judge, T. A., & Watson, D. (2002). The confounding role of personality and trait affectivity in the relationship between job and life satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior,23(7), 815–835.

Helliwell, J. F., & Barrington-Leigh, C. P. (2010). Viewpoint: Measuring and understanding subjective well-being. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique,43(3), 729–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5982.2010.01592.x.

Heslin, P. A. (2009). Better than brainstorming? Potential contextual boundary conditions to brainwriting for idea generation in organizations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,82(1), 129–145.

Jaensch, V. K., Hirschi, A., & Freund, P. A. (2015). Persistent career indecision over time: Links with personality, barriers, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior,91, 122–133.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,86(1), 80–92.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002a). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,83(3), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.693.

Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002b). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,87(3), 530–541.

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology,83(1), 17–34.

Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1993). Another look at the job satisfaction–life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology,78(6), 939–948.

Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., Sianoja, M., de Bloom, J., Korpela, K., & Geurts, S. (2017). Identifying long-term patterns of work-related rumination: Associations with job demands and well-being outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,26(4), 514–526.

Kross, E., & Ayduk, O. (2011). Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science,20(3), 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411408883.

Kuppens, P., Realo, A., & Diener, E. (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,95(1), 66–75.

Lakdawalla, Z., Hankin, B. L., & Mermelstein, R. (2007). Cognitive theories of depression in children and adolescents: A conceptual and quantitative review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review,10(1), 1–24.

Lindenberger, U., & Potter, U. (1998). The complex nature of unique and shared effects in hierarchical linear regression: Implications for developmental psychology. Psychological Methods,3, 218–230.

Luhmann, M., Hofmann, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,102(3), 592–615.

Luthans, F. (2005). Organizational behavior (10th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology,60(3), 541–572.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist,56(3), 239–249.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005a). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin,131(6), 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Lyubomirsky, S., Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Nelson, S. K. (2015). Thinking about rumination: The scholarly contributions and intellectual legacy of Susan Nolen-Hoeksema. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology,11, 1–22.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research,46(2), 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005b). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology,9(2), 111–131.

Maddux, J. E., & Volkmann, J. (2010). Self-Efficacy. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of Personality and Self-Regulation (pp. 316–331). Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken.

Madrid, H. P., Patterson, M. G., & Leiva, P. I. (2015). Negative core affect and employee silence: How differences in activation, cognitive rumination, and problem-solving demands matter. Journal of Applied Psychology,100(6), 1887–1898.

McGuirk, L., Kuppens, P., Kingston, R., & Bastian, B. (2017). Does a culture of happiness increase rumination over failure? Emotion. http://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000322.

Michl, L. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Shepherd, K., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,122(2), 339.

Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Ruminative self-focus and negative affect: An experience sampling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,117(2), 314–323.

Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: Extra-role efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal,42(4), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.2307/257011.

Nesselroade, J. R. (1991). Interindividual differences in intraindividual change. In L. M. Collins & J. L. Horn (Eds.), Best methods for the analysis change: Recent advances, unanswered questions, future directions (pp. 92–105). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Newman, D. B., & Nezlek, J. B. (2017). Private self-consciousness in daily life: Relationships between rumination and reflection and well-being, and meaning in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.039.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,100(4), 569–582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,61(1), 115–121.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science,3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.

Oishi, S. (2002). The experiencing and remembering of well-being: A cross-cultural analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,28(10), 1398–1406.

Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2004). Nature, functions, and beliefs about depressive rumination. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 3–20). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Purdon, C. (2004). Psychological treatment of rumination. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 217–240). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Querstret, D., & Cropley, M. (2012). Exploring the relationship between work-related rumination, sleep quality, and work-related fatigue. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(3), 341–353. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/ocp/17/3/341/.

Querstret, D., Cropley, M., & Fife-Schaw, C. (2017). Internet-based instructor-led mindfulness for work-related rumination, fatigue, and sleep: Assessing facets of mindfulness as mechanisms of change. A randomised waitlist control trial. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,22(2), 153–169.

Querstret, D., Cropley, M., Kruger, P., & Heron, R. (2016). Assessing the effect of a Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)-based workshop on work-related rumination, fatigue, and sleep. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,25(1), 50–67.

Roberts, B. W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2003). Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,84(3), 582–593.

Robinson, M. S., & Alloy, L. B. (2003). Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research,27(3), 275–291.

Rothbard, N. P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly,46(4), 655–684. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094827.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review,5(4), 296–320.

Scholz, U., Doña, B. G., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 242–251. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/jpa/18/3/242/.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio (pp. 35–37). Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson.

Sexton, K. A., & Dugas, M. J. (2009). Defining distinct negative beliefs about uncertainty: Validating the factor structure of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Psychological Assessment,21(2), 176–186.

Sheldon, K. M., & Houser-Marko, L. (2001). Self-concordance, goal attainment, and the pursuit of happiness: Can there be an upward spiral? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 152–165. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/80/1/152/.

Spasojević, J., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Maccoon, D., & Robinson, M. S. (2004). Reactive rumination: Outcomes, mechanisms, and developmental antecedents. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 43–58). England: Wiley.

Speier, C., & Frese, M. (1997). Generalized self-efficacy as a mediator and moderator between control and complexity at work and personal initiative: A longitudinal field study in East Germany. Human Performance,10(2), 171–192.

Stansfeld, S. A., Shipley, M. J., Head, J., Fuhrer, R., & Kivimaki, M. (2013). Work characteristics and personal social support as determinants of subjective well-being. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081115.

Strobel, M., Tumasjan, A., & Spörrle, M. (2011). Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: Self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology,52(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00826.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Tait, M., Padgett, M. Y., & Baldwin, T. T. (1989). Job and life satisfaction: A reevaluation of the strength of the relationship and gender effects as a function of the date of the study. Journal of Applied Psychology,74(3), 502–507.

Thomsen, D. K., Schnieber, A., & Olesen, M. H. (2011). Rumination is associated with the phenomenal characteristics of autobiographical memories and future scenarios. Memory,19(6), 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.591533.

Tkach, C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How do people pursue happiness? Relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies,7(2), 183–225.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research,27(3), 247–259.

Tsai, W., Chang, E. C., Sanna, L. J., & Herringshaw, A. J. (2011). An examination of happiness as a buffer of the rumination–adjustment link: Ethnic differences between European and Asian American students. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 2(3), 168–180. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/aap/2/3/168/.

Van de Vliert, E., & Janssen, O. (2002). “Better than” performance motives as roots of satisfaction across more and less developed countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,33(4), 380–397.

Vassar, M. (2008). A note on the score reliability for the satisfaction with life scale: An RG study. Social Indicators Research,86(1), 47–57.

Vassilopoulos, S. P., & Watkins, E. R. (2009). Adaptive and maladaptive self-focus: A pilot extension study with individuals high and low in fear of negative evaluation. Behavior Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.05.003.

Vieluf, S., Kunter, M., & Van de Vijver, F. J. (2013). Teacher self-efficacy in cross-national perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 92–103. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0742051X13000954.

Wenzel, M., von Versen, C., Hirschmüller, S., & Kubiak, T. (2015). Curb your neuroticism—mindfulness mediates the link between neuroticism and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences,80, 68–75.

Whitmer, A., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Brooding and reflection reconsidered: A factor analytic examination of rumination in currently depressed, formerly depressed, and never depressed individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research,35(2), 99–107.

Woody, M. L., Burkhouse, K. L., Birk, S. L., & Gibb, B. E. (2015). Brooding rumination and cardiovascular reactivity to a laboratory-based interpersonal stressor. Psychophysiology. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12397.

Wright, T. A., Bennett, K. K., & Dun, T. (1999). Life and job satisfaction. Psychological Reports,3(84), 1025–1028.

Yook, K., Kim, K. H., Suh, S. Y., & Lee, K. S. (2010). Intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and rumination in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders,24(6), 623–628.

Zanon, C., Hutz, C. S., Reppold, C. T., & Zenger, M. (2016). Are happier people less vulnerable to rumination, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress? Evidence from a large scale disaster. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica,29(1), 20–26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karabati, S., Ensari, N. & Fiorentino, D. Job Satisfaction, Rumination, and Subjective Well-Being: A Moderated Mediational Model. J Happiness Stud 20, 251–268 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9947-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9947-x