Abstract

This paper pilots a different approach to the study of informal settlements, typically conceived as chaotic, disorganised and lacking social cohesion. We provide a different reading of social life in an informal settlement. While its social life may be different from other parts of the urban metropolis, its social relations are not absent. Through the use of network theory, we will demonstrate that social relations in settlements have developed a considerable level of complexity. Using the case study of Mathare Valley, an informal settlement in Nairobi, we explore the dynamics of social networks with the aim of providing a more integrated understanding of life in slums. Based on survey data, focus groups/workshops and interviews, we established that residents depend on a network of strong, highly familial ties. Life is typically defined by neighbourhood bonds and friendship. This structure underpins the development of referral systems to access services and find work. The settlement has a syncretic governance structure made up of governmental and self-styled leaders who act as gatekeepers to varying degrees. We geo-coded data to conduct a more detailed social network analysis, which revealed the positive attributes of networking as opportunities for innovation and forming weaker ties within and beyond the settlement. The negative aspects of strong ties lead to the exclusion of more vulnerable residents. In conclusion, we propose the social networks approach as essential in understanding informal settlements. A holistic understanding of informal settlements will not only overcome narrow conceptions but may also encourage networked thinking for urban planning and design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Networks and Informal Settlements

This paper will introduce a new conceptual perspective to the study of informal settlements, which highlights the complex, self-organising nature of social interactions and relations.Footnote 1 Such an approach will overcome prevailing narratives of informal settlements that depict them as anti-social (United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2003), ‘disorganised’ (Kuiper 2012), conflict-ridden (Samaio 2018) and most ‘chaotic’ (Vidal 2018). As such, informal settlements are conceived as lacking social order, social cohesion or social life. It is the purpose of this paper to make a critical examination of these wildly views and to suggest a different approach to the analysis of life in informal settlements as based on recent developments in network theory. Network theory will provide a framework that reveals a very different picture about social life, social relations and social interactions in informal settlements, which are far more complex and stable than reflected in current thinking. In a similar fashion, Whyte (1943, p. xvi) in his famous study of the Street Corner Society (an Italian-American slum in Boston) wrote ‘The middle-class person looks upon the slum district as a formidable mass of confusion, a social chaos. The insider finds in Cornerville a highly organised and integrated social system’. Such a perspective of bringing back the social into informal settlements is highly relevant (see also Morgner 2014) because a consequence of the asocial framing of these areas is that models of intervention focus mostly on improving material conditions, that is, providing physical infrastructure and basic services. To capture the social world of informal settlements, we employ the concept of the network to unravel the complex entanglements and relationships in this world, but also to demonstrate its social limits.

There is growing literature on informal settlements and urban development that acknowledges the usefulness of network theory. For instance, the notion of the urban as an assemblage, adapted from theories of rhizomatic networks as developed by the French philosophers Deleuze and Gutari, has been employed to critically approach the distinction between formal and informal (Dovey 2012). The idea of network is employed as a tool for a normative or critical urbanism (McFarlane 2011). Elsewhere, the idea of social capital, as developed by Pierre Bourdieu, is used as a resource for enabling network chain interactions, in particular, with a focus on trust and informal settlements (Kassahun 2015). However, the bulk of the research in this area applies the idea of social networks in a rather loose way. Examples include research on community resilience in informal settlements. For instance, research by Harte et al. (2006) revealed that social networks played a decisive role in mitigating the impact of a major fire in an informal settlement in Imizamo Yethu, Cape Town, South Africa. Likewise, Amuyunzu-Nyamongo and Chika Ezeh (2005) demonstrated that social networks in informal settlements provide resilience in times of crisis. Research on migration has also adopted the idea of the network. This research may address the role of family ties in bridging urban-rural migration (Mberu et al. 2013) or consider the role of support networks among refugees that migrate to informal settlements (Thomson 2013). Finally, there is a range of studies examining the role of social networks from the perspective of infrastructure issues. Examples include investigations into social networks and waste management (Gutberlet et al. 2017), economic networks (Meagher 2006; Serneels 2007), family networks and health (Ayuku et al. 2004; Musalia 2006).

While this paper will contribute to this emerging debate, we also recognise the limitations inherent in the state of the art in this field. Many of these studies focus on single phenomena, such as networks and migration, networks and water management, or networks and trust. Such a focus on particular phenomena may lead to a contradictory impression of social science that operates with an understanding of networks as defined by notions of connectivity, entanglement, association or affiliation—in short, where a network seems to represent a more encompassing approach to social life (see Latour 2007; Kadushin 2011). We therefore believe that the above-mentioned studies do not employ the concept of the network to its full potential to reveal the complexity of social life in an informal settlement, which is the focus of this paper.

Network Theory: a Brief Overview

Social network analysis is broadly devoted to the study of social relationships with emphasis on the relational (Morgner 2020). Relational refers to the type of association that links up any object or subject (people, places or resources), and the links can represent any relational ordering between them, for instance, intimate relations, informal/formal relations, contractual relations, family relations or institutional relations (McCulloh et al. 2013). Earlier approaches to network theory and, in particular, to its more applied form as social network analysis mainly considered networks from the perspective of who is related to whom, for instance, and whether these relationships are symmetrical—reciprocal—or asymmetrical—hierarchical. Typically, symmetrical relationships are described as representing friendship based on overall similarities, exchanges and social distance, whereas asymmetrical networks may be represented as models of authority with a top-down flow or a one-sided form of relationship (see Laumann et al. 1970; Wellman 1979). More recent literature has moved somewhat beyond an understanding of who is connected to whom, to how the connection between two or more entities (nodes) brings about a specific meaning. For instance, Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory considers how agency is produced. Agency (intention, subjectivity, etc.) is not simply a quality of an actor but is inscribed through associations (Latour 2007). Harrison C. White (1992) has described similar considerations. Entities (White 1992: 65, calls them ‘identity’) ‘come to perceive the likelihood of impacts to other identities in some string of ties and stories. The social result is called a network’. A network, as such, is not simply a connection of lines in a static space but ‘becomes constituted with story’, a ‘network of meanings’ (White 1992: 67).

In this paper, we used an approach combining these earlier and later developments. On the one hand, attention is paid to the connections, to who is related to whom (and who is excluded) and in what way, but attention is also paid to the meanings and stories that are mediated in these networks. In this context, a number of network concepts need further elaboration (see Kadushin 2011).

Informal settlements are typically seen as densely populated with negative undertones of overcrowding or overpopulation, and, more importantly, density is seen as a geographical category that measures the number of inhabitants in relation to a certain geographical area. This overlooks that density can also be conceptualised as the number of actual direct connections compared to the possible direct connections. This is important, as density is at the heart of community life that includes forms of social support but also social control because people can sense what others are doing and sanction their behaviour. Typically, large cities have low density, whereas villages have high density. As mentioned above, informal settlements are often described as chaotic, lacking social coherence. From the perspective of network theory, this aspect is theorised through two interrelated concepts: structural holes, defined as a lack of social relations and connections (Burt 1992), and the notion of strong and weak ties (Granovetter 1973). Weak ties refer to acquaintances—people with whom we are less likely to be socially involved—in contrast to close friends (strong ties). Networks that would consist of only acquaintances would have a low density and a tendency to be atomistic, whereas networks of close friends would be quite closely knit. Structural holes are the lack of social ties, strong or weak. While it is normal, to a certain degree, that not everybody is connected to everyone, special gatekeepers or brokers may emerge in larger settings to overcome structural holes. They hold far more connections and have greater centrality (Freeman 1979). One can get to other members of the network through them. They are important for the replication and particularly the maintenance of larger network settings. This theoretical framework, as well as other mentioned concepts, will inform the interpretation of data, help structure our findings and shed more light on the social coherence and quality of social relations in informal settlements.

Methodology, Data Collection, and Case Selection

To illustrate how network theory can shed a different light on social life in informal settlements, we conducted secondary quantitative data analysis of a recently collected dataset, which we complemented with a series of in-depth interviews with people from Mathare, an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. The Mathare Valley is one of the oldest informal settlements in Nairobi, consisting of several slums (Kigochie 2001). The entire Mathare Valley covers approximately 73 ha in both Starehe and Kasarani Divisions of Nairobi (Muungano Support Trust et al. 2011). The Mathare and Gitathuru Rivers that traverse the settlement are part of the larger Nairobi River watershed (Muungano Support Trust et al. 2011). Based on national census statistics, the population of Mathare Valley has more than doubled, growing from 80,309 residents in 2009 (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Kenya (KNBS) 2019) to 206,564 in 2019 (KNBS, 2019). However, population estimates vary depending on the prevailing agenda. Bloated media reports in the Kenyan press claim that the slum has over half a million residents who live in squalid conditions and are plagued with crime and violence (Gettleman 2006; Otieno 2016). As described by Otieno (2016), ‘There is absolute inaccessibility to the most basic amenities, among them food, water, shelter and healthcare. Road infrastructure is totally non-existent…’ in Mathare. Mathare is also well known for gang wars fuelled by ethnic rivalry and political differences (Auma and Anyango 2017; Van Stapele 2010). The depiction of the slum in Kenya’s mainstream media is in line with the overall image of slums, as mentioned. To look behind this picture was one of the reasons we selected Mathare as a case study. Furthermore, Mathare is one of the oldest informal settlements in Nairobi whose high social density suggests that structures of social reproduction have developed.

The quantitative data for the project was derived from a two-year collaborative research project (2017–2019) known as the Co-Designing Energy Communities (CoDEC), hosted by the University of Nairobi (Ambole et al. 2019; Kovacic et al. 2019). While the aim of the research was to propose integrated solutions to household energy challenges, the scope of the quantitative survey was not limited to energy. Previous talks with community leaders, as well as the lack of research in this field, prompted us to conduct a far more encompassing survey that focused on the social structure and social relations of households in the informal settlement. The field research in Kenya began in June 2017 with a household survey, which included questions on household energy used for cooking, heating and lighting, in terms of type, cost and access, but also focused on the socio-economic status of household members, quality of life and social relations in the informal settlement. The 100 households included in the survey were selected from four villages of Mathare Valley—Mathare 4A, Kaimutisya, Mlango Kubwa, and Kosovo. These four villages were sampled of the 13 villages in the settlement to represent diversity in size, density, shape and housing typologies (Table 1).

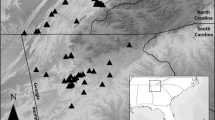

The 100 households were selected using a spatial sampling framework that reduced sampling bias by selecting respondents from alternating grids cells. Within grid cells, the selection of respondents was based on a combination of random and convenience sampling (Fig. 1). To account for the differences in their population sizes, allocation of respondents to the villages was done pro rata based on the 1999 National Population and Housing Census. This yielded a distribution of 17 respondents from Kiamutisya, 20 from Kosovo, 30 from Mathare 4A and 33 from Mlango Kubwa. The survey and mapping exercise, which took six days, was carried out by the researchers from the University of Nairobi and six Mathare residents working as co-researchers.

Preliminary results from the survey and mapping informed a subsequent number of focus groups held at the University of Nairobi and at Mathare in September 2017, June 2018 and June 2019. The focus group participants (13 at the first meeting, 16 at the second and 18 at the third) included household owners, community leaders, small business owners, college students, teachers, international academics from Colombia, South Africa, the UK and Uganda, officials from the National Ministry of Energy and from the Nairobi county offices in charge of public health in Mathare and an environmental assessment expert.

The first focus group addressed social practices concerning the use of energy, and as such, addressed questions on how people obtain access or how access is managed, which in both cases is based on complex networks of referral to find someone to make a connection to the grid. These contacts involve personal referral through relatives, neighbours or friends, but essentially lead to business-like contacts with people in the settlement who offer their skills to access the electrical grid and who will be responsible for all follow-up maintenance. Such follow-up visits are successful because finding a job requires positive feedback for future referrals.

The aim of the second focus group was to illustrate the energy stories recounted by the residents themselves. The participants included co-researchers who were involved in previous research activities, energy providers, home owners and community leaders from the settlement. This focus group was facilitated by an illustration expert, with the participants first discussing stories around energy issues and then selecting three energy stories on informal electrical connections, a defunct biogas project and an improvised energy-saving sawdust stove used in the settlement. The illustration exercise provided a visualised account of the process of accessing various types of household energy and the development of energy-related business models based on the social networks that would either underpin these structures or even trigger innovations in the settlement. We used this illustration technique to overcome narrative limitations. We had noticed in our previous encounters that oral and written communication had a tendency to exclude people from the settlement, whereas the focus on visuals seemed to empower people to tell their real-world experiences.

The third focus group concerned geo-spatial networks in the settlement. We sought to understand the linkages people have within and outside the settlement based on their daily activities—going to work, school, church, shopping and their leisure pursuits. This workshop also used a mapping exercise. We provided a map of Nairobi that only included its borders and the location of Mathare. The participants were divided into three groups and asked to provide a network of the above-mentioned places, including estimating distances and travel times. We asked them to find certain landmarks and estimate their distance from the settlement.

In addition to the quantitative data and holding focus groups, we conducted a number of in-depth interviews with selected community leaders that lasted between one and two hours and were conducted in Swahili and English. The questions in the interviews were directed at understanding the nature of social relations (symmetric or asymmetric), the role of referrals, finding employment and childcare. The interviews were transcribed and analysed with NVivo. Extracts were translated into English for this publication. Finally, we conducted a number of follow-up phone calls with local residents to address specific issues more fully.

Findings and Discussion

Strong Bonds and Networks of Referral

Strong Ties and Networks in Mathare

While informal settlements are described as chaotic or even atomistic in the context of a network approach, this research reveals that strong ties sit at the heart of social relations in Mathare’s informal settlement. When we asked people to talk about social life in the informal settlement, they answered in terms of home, describing it as like living in a village, like living within a large family, something that cannot be left behind: Kwetu Mathare (‘our home Mathare’) or Mathare hata kama umehama, haikutoki (‘even when you leave Mathare, it doesn’t leave you’) (local residents, verbal communications). There is a strong tendency for people born in the settlement to stay there all their lives. Even women who left the settlement upon marrying outside the community eventually returned to the settlement drawn by familial feelings in this social context. The ‘extended family’ is typically described in terms of an imagined community (Anderson 1991), strongly related to tribal and ethnic categories that organise life as if it were a village. As such, people in the settlement refer to others under such an umbrella of familiarity: Mwenzangu ni jirani ama rafiki (‘one is either a neighbour or a friend’). This is also illustrated by the prevalence of a dominant ethnic group in each of the villages that make up the settlement. For example, ‘Kosovo village has the Kikuyu ethnic group, 4B and 4A villages have Luos, Kitathuru has Luyhas, and 3B has Kambas’ (community leader, verbal communication). Finally, the space of the settlement and Nairobi itself are experienced through strong ties only (see Fig. 2).

For instance, when we asked residents to estimate distances within the settlement or nearby and if they were able to identify them on the map, distances as well as travel times could be actually measured based on the information derived from their immediate social networks. There were few links to networks outside that social world, so residents struggled to identify places, like major landmarks, roads or buildings. The experience of geographical space was largely restricted to the strong social networks in which people could operate.

The notion of strong (versus weak) ties was first developed by Mark Granovetter (1973). He suggested that the strength of a tie should be defined based on the amount of time invested in the relation, the emotional intensity or intimacy, and the reciprocal services that are shaped by it. Strong ties are typically defined as those with a high level of mutual engagement, intimacy and positive social behaviour. Personal trust and personal knowledge are key in these networks. Weak ties refer to people that we know slightly. They are more like acquaintances. We share perhaps a more formal and less intimate relation with them. As such, strong and weak ties should not be seen as one being good and one being bad. As Granovetter (1995) explains in his book ‘Getting a Job’, they play different roles in the structure of social life. For instance, Granovetter (1995) reported in this study that 17% of the people who were looking for a job learnt about their jobs from a close friend, 28% learnt about it from someone they barely knew and 56% said that they learnt about it from an acquaintance. Granovetter (1995) explains that strong ties connect us with family and friends to whom we are very close and who would do anything for us, but the chances are far more likely that they know the same people we do. As such, they have less to offer because of the high familiarity with each other’s contexts. Weak ties or acquaintances do not come from the same context and, as such, they can access other networks; they connect one to a wider social network or provide access to a wider network of information, and thus may provide more opportunities for employment.

Within the context of this research, it is the emotional colouring of the tie that stands out most, where one has the feeling of being part of a larger family through such homophilous relations (see Mollica et al. 2003). Likewise, these friendships are influenced by ethnic affiliation giving the impression of an ‘extended family’. As mentioned, this ethnic component is further strengthened through spatial settlement patterns in which people of the same ethnic family live in proximity to each other. As a consequence, the organisation of the household with its daily needs—food, work, leisure, and basic services—is structured along these horizontal network chains, as evidenced by the settlement patterns aligned with ethnic groupings. When asked what determines where one lives or settles, our key informants confirmed that one’s personal relationships (within ethnic contexts) are the greatest determinant (see also Kinuthia 1988). These strong ties lead to a village-like atmosphere or small-world network with a great sense of familiarity and emotional attachment to the place. Respondents of the survey often expressed a homey and warm feeling when talking about their circumstances (see also Wellman 1979).

Such an image of social life based on strong ties in the informal settlement runs counter to public assumptions that describe life in these places as disorganised or even chaotic. Quite the contrary, people invest considerable time into building and maintaining social order. For instance, it was apparent that residents of the informal settlement spend considerable time exchanging information, visiting family and friends, attending religious activities and being part of social groups, such as self-help groups (chama). Collective agency is also a common phenomenon. This is evident in the way families come together to solve a common problem: ‘For families that want their older children to have their personal space, they rent a room together with other families so that their older children can live together. For example, two families with teenage sons rent a separate room for their two boys to live together in. However, such teenage boys who live separately from their families may acquire antisocial behaviours or get involved in illegal activities’ (community leader, verbal communication). Strong social ties sit at the core of organising life in informal settlements. We will look at a number of social issues and social structures that have developed in managing social relationships in such a large informal settlement, but within a framework of ensuring family-like relationships. We will demonstrate how strong ties achieve considerable complexity in building social order in the settlement, but we will also discuss how the near absence of weak ties creates limitations to that social order.

Strong Ties and Structures of Referral: the Case of Electrical Connections and Establishing a Business

Tribal or village-like structures are typically associated with low levels of complexity because they do not have higher levels of social differentiation (Eisenstadt 1961; Richerson and Boyd 1999). While this might apply to smaller, relatively isolated societies, strong ties are utilised within large informal settlements to achieve a certain degree of differentiation in which a division of labour can be organised. High redundancy in the network, that is, people knowing each other, people sharing an identity and having something in common, is a key component from which such social differentiation derives (Luhmann 1977). Strong ties can be mobilised for structures of referral. The strong ties are more likely to be activated for the flow of referral information because members of the same networks possess greater credibility (see also Brown and Reingen 1987).

This structure of referrals enables people in the settlement to delegate and also regulate the provision of services, which may include access to water or electricity. For instance, even though 93% of households are connected to the national grid, 50% of these are informal connections, according to the survey results. Current literature has mainly focused on questions of the legality of such connections (Karekezi et al. 2008; Lambe and Senyagwa 2015). However, the focus of network analysis and the notion of complexity provide a different perspective. If about 50% of the connections are mainly self-organised, it means that several hundred thousand people are receiving electrical service and maintenance not based on an institutional context, with its training, certifications and regulations, leaving one to wonder how such a complex task is achieved.

To illustrate this process, we collected stories from people in the settlements using visual story diaries. As shown in Fig. 3, the process of getting an informal electrical connection in the settlement is dependent on referral from a neighbour. This means that the informal electrical connectors are well known within the settlement, especially as some of them may have a kiosk from which they operate. To get started, the connector provides the would-be customer with a list of materials to purchase, such as wires and switches. The connection is then done by tapping directly into the power transformer. As dangerous as this may seem, connectors are well-versed in the process and even train their customers how to quickly disconnect their household supply in case of a power surge (see Fig. 4).

In contrast with Granovetter’s (1995) research that pointed out the role of weak ties in finding a job, to find work within or outside the settlement, people depend mostly on the referral system. For example, for domestic help jobs outside the settlement, employers from around the city hire primarily based on referrals. For temporary jobs, people go to certain sites within the city where potential employers come to look for temporary labourers. People with employer networks usually act as sub-contractors; a sub-contractor for a construction site, for example, will assemble their own team from within the settlement and manage them on site as well. Entrepreneurs within the settlement usually start their businesses next to or in front of their houses. Local businesses within the settlement do not pay local or national fees or taxes, so starting a local business does not require licensing or formal permission and is therefore easy to start (community leader, verbal communication, 2019).

Such structures of referral are not just one-way; finding information about who can provide an electrical connection is an ambiguous task due to the informal nature of these connections. They cannot be openly advertised but require a more selective approach. Furthermore, being referred demonstrates that one has a certain amount of social credit or trust. This is important in a world that operates without independent norms or quality assurance, such as professional certification. Referral thus works in both directions: (1) it provides information on who can provide informal electricity within the context of an ambiguous legal status, and (2) it includes a form of social control for the quality and maintenance of such connections.

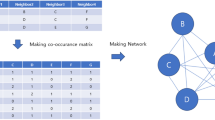

Mapping Energy Access and Business Opportunities in Mathare

The previous chapter addressed the role of referrals, how they derive from the structure of strong ties and how they enable people in the informal settlement to self-organise a certain level of social differentiation. In line with network theory, we also conducted a social network analysis through the use of mapping tools that illustrate the patterns of referrals when sourcing for cooking and lighting energy (charcoal, gas, paraffin and wood) or pursuing business opportunities. The first part of the mapping showed the spatial links between the sampled households and locations where respondents sourced their energy for household use. The visualisation affirmed that the settlement has highly developed social networks that inform the social relations among the residents. The settlement has a competitive commodity market, and because prices are almost standardised, it was expected that residents would source energy from the facility closest to them. Contrary to this assumption, the study found that 58 respondents preferred source locations that were not the closest facility. An example of these networks is shown for Mlango Kubwa and Kiamutisya (Fig. 5).

Discussions with key informants revealed that there are, in principle, two types of referrals for such locations. The first is based on immediate personal networks, such as asking a neighbour. In this case, there is a strong tendency to source materials in proximity to one’s home, which we explained in the previous chapter. However, there is a second type of referral that is based on gatekeepers. We will explain this type in more detail in the following section. Gatekeepers have access to wider social networks and are therefore able to provide referral to locations outside one’s immediate networks. This is the case of those people shopping farther from their homes. For instance, in Mathare 4A village, it was observed that the majority of households did not source energy from the two facilities closest to their homes. In Fig. 6, it can be noted that respondent Q16 sourced energy from sources 7 and 15, avoiding sources 8, 9 and 16; respondents Q37, Q38 and Q67 preferred a source far away, and respondent Q66 preferred the closest facility (9), but with an alternative, source 6, which was farther than three other energy sourcing facilities.

The second part of the mapping assessed work locations relative to respondents’ homes. All home-to-work links were plotted on a map and travel distances computed based on road network distances. Results showed that more than 40% of the respondents’ work locations were less than 500 m from their houses (Fig. 7). This is in strong contrast to metropolitan life in Nairobi, where the majority of inhabitants rely on the local bus system, matatus, to travel from home to work and spend, on average, more than an hour to go to work and return home (Salon and Gulyani 2019). People typically expect to commute as it enables finding work from a wider range of opportunities. Their choice is thus driven by finding a match of their professional background with a job opportunity (Jansen 1993). However, as business owners in the settlement explained to the researchers, they have different reasoning. A considerable number of residents engage in informal businesses (i.e. 48% of households depend on local businesses) because having a workplace inside the settlement maximises relations with others and keeps their referral networks alive. It is through these personal referral networks in a settlement that businesses have sustained income creation. The spatial network analysis thus reveals how economic activities and personal networks are interwoven.

The isolation of the networks confirmed how the referral structures underpin social differentiation and thereby a more complex organisation of social relationships in the settlements. The referral itself is based on strong ties and homophily. The strong ties not only provide access to information, like a friendly and trustworthy recommendation, but they also serve as a form of social control. Gaining a negative reputation, for instance, by providing faulty service is likely to seriously harm the possibility of future referrals in such a setting. The social network analysis and its visualisation revealed another feature of the structure of referrals, adding different layers of complexity. As shown in Fig. 5, some households provide more referrals than others. Thus, the distribution of referrals is unequal, which will be explored in the next chapter.

Social Capital and Networks: Gatekeepers and Opinion Leaders

Personal trust and knowing other people are at the heart of the strong ties that shape social life in Mathare. However, as the social network analysis revealed, it seems that not all people in the settlement possess the same levels of trust and knowledge—some seem to stand out. They are more often consulted in the process of social referrals. Pierre Bourdieu (1986) captured this unequal distribution through the notion of social capital. Bourdieu (1986: 249) argues that the ‘network of relationships is the product of investment strategies’, in terms of exchanges and interactions. However, such investments are not only of an economic nature but may also consist of other forms of capital. Social capital is linked to mutual acquaintance and recognition in which a person has achieved a certain social credibility in the network. This credibility gives the person an elevated status to become a gatekeeper or an opinion leader, for instance, within their network. They become far more likely to be consulted, and through their recommendations, they increase their social capital.

We will use this notion of social capital to unravel the more complex leadership structure in the Mathare Valley settlement, which is harder to unpack due to the crisscross between horizontal and vertical networks of elected representatives, government officials and self-styled community mobilisers, who each broker and connect the settlement with socio-political opportunities within and outside the settlement (see Burt 2005).

In terms of government representatives or leaders, the assistant county commissioner (formerly known as the district officer) is the highest government official with whom residents can deal, according to the key informants. Under the assistant county commissioner, there is a senior chief and an assistant chief. These assistant chiefs exercise direct control in their part of the settlement and are therefore viewed negatively as ‘government operatives’ by the community. To complicate matters further, the 2010 constitution of Kenya provides for elected members of the county assembly (MCAs) who should ideally be the local representatives of the community. However, MCAs do not seem to exercise much authority: ‘The MCA has little role in governing local issues. They only disburse bursaries. Residents do not consult them.’ (Community leader, verbal communication, 2019).

These governmental representatives or leaders possess very little social capital in contrast to the community mobilisers, who are viewed as trusted leaders of the community able to exercise a gate keeping function mainly in the form of social control. They take on a representative role and often mediate between external formal organisations (such as utility providers, development agencies, and research institutions) and households (see Muungano Support Trust et al. 2011). The community mobilisers we talked to are typically younger. Their social capital in the network is based on their interests being in line with the interests of the people in the network and not in their personal gain: ‘They are the most respected by the community because they deal with community issues…[whereas] village elders, for example, are only interested in projects if there is personal financial gain for them’ (community leader, verbal communication, 2019). As demonstrated in other research (Ghosh and Goswami 2014), altruism, as the ability to feel responsibility for others without getting an immediate return, is considered acting in a way of friendship and sharing within a family. Thus, credibility and social capital are not linked to, for instance, superior knowledge or superior skills, but rather to the person’s ability to refrain from engaging with others based on purely personal gain. In this sense, social capital flourishes if it links to the structure of strong ties. Based on this standing, community mobilisers have acquired a number of roles in the network. First and foremost, they are gatekeepers or opinion leaders that can bridge large networks. They also have representative functions, such as voicing concerns to the government (managing the network externally), but also serve as mediators for internal conflicts (managing the network internally).

Gatekeepers or opinion leaders add another level of complexity to the organisation of social network theory in the settlement. Larger settlements of several hundred thousand people reach their limits when it comes to the dissemination of information within them. They might face a breakdown or unequal distribution, which is likely to harm their sense of community. This is when the gatekeepers and opinion leaders play a crucial bridging role. In the flow of information in the network, gatekeepers are at the centre and more exposed to new information than others. Based on the surplus, they can develop a more informed opinion (summarising, organising and classifying information), which, due to their credibility, is passed back into the network (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955). They thus ensure that a sense of commonality does not rely on everybody in the network knowing everything but is based on their elevated status within the network. In the following sub-section, we will explore further this notion that not everybody can be related to everybody and demonstrate how this leads to other possibilities for social organisation.

Networks, Brokerage and Entrepreneurship

Although the core networks are based on strong ties and homophily, these networks are based within an extremely large settlement of over 80,000 people. In such a large settlement, not everybody is or can be related to everybody, and not everybody can be connected to each other so structural holes emerge (see Burt 2004). However, such structural holes are not just a limiting quality in terms of distributing information, for example, but the unequal distribution of such information caused by structural holes is a key stimulus for innovation in the settlement (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986). It enables the existence of non-redundant information and thereby offers new opportunities to serve those who cannot relate to one another.

An example of innovation opportunities and their challenges is illustrated by the approach of those external to such immediate connections. Again, we worked with residents using visual story diaries to illustrate this idea in the case of the installation of a biogas plant by a multi-national company as part of their corporate social responsibility (Fig. 8). A representative of the company had explored the area. His walks led him near a cow farm where he learned about the problems of dealing with large amounts of cow manure. In the same walks, he spotted unused land and visited local households to learn about cooking practices in informal settlements. With the same detached view, he noticed a series of social opportunities that did not link up but that could trigger innovation through the brokerage of such opportunities. In linking up these opportunities through his role as a social broker, he envisaged a social innovation whereby the cow manure would power a small biogas plant that might not only provide free cooking gas for residents but also become a hub for community action, such as feeding programs for orphans and organising bakery classes. In larger social networks, not everybody can be connected to everybody—gaps and holes emerge (Burt 2004). However, such gaps or holes should not be seen as merely a lack of social engagement or social relations but may actually become sources that stimulate new forms of networking. The differential divides of distributing information that emerge in such a complex social network can be utilised by entrepreneurial brokers to introduce social innovations if they are able to mediate linkages across different social networks (see Gould and Fernandez 1989). The example also shows the fragile and perhaps limiting nature of innovations. If one element of the network is withdrawn, the entire chain collapses. In this case, the plant failed after a year when the owner of the cow farm went into administration. The network had not achieved adequate sustainability, not just in brokering networks but also in investing in their maintenance.

However, not only non-residents but also residents act with an entrepreneurial mind, and again, personal networks matter. They serve a two-fold function. The holes and gaps provide sufficient room for social experiments, like testing new ideas, but they also provide the back-up and motivational support if an idea fails. This ecology of the network stimulates an entrepreneurial mindset in the settlement. As evidenced by the survey, nearly 50% of the households source their daily goods from businesses within the settlement.

A possible example of how innovation begins from within the network in Mathare is the use of the improvised sawdust stove (jiko) (Fig. 9). In reaction to the government ban on charcoal production from all public forests, residents of Mathare turned to using sawdust jiko on an improvised cook stove. This was because the price of charcoal had increased, making it unaffordable for most people in the settlement. According to our interviews, the sawdust innovation initiative began in the settlement without any external influences from when it started being fabricated. The innovation is prompted by a need within the community and is purely an initiative by the community members. It was started by the women who run small eateries and relied on charcoal for their energy needs. However, the innovation was not restricted to their immediate needs. Social network provided the moral support to test new ideas. Based on this testing, people in the settlement realised that the is a wider application of sawdust in particular for its use in people’s home as it produces less smoke. Furthermore, the sawdust could be easily produced the settlement turned this innovation also into an entrepreneurial opportunity. Thus, through connecting various local networks, it was through actions in a grassroots network that the idea of improvising an existing cook stove to use sawdust emerged, linking the production of materials to existing networks for sourcing materials in the settlement. In other words, local networks led in innovations to answer the call for a more affordable and sustainable source of household energy. In this way, local communities can spearhead energy transitions that are contextualised by local resources and ingenuity (Cross and Murray 2018).

Informal Settlements and Weak Ties

The central form of organising social relationships is through strong ties. We have described how this type of social linkage underpins the development of a complex social life in, for example, division of labour and social innovation. As mentioned, weak ties are not the opposite of strong ties but rather serve as an alternative form of organising social relationships. Social relationships rely on acquaintances or strangers with whom one shares a common cultural background. To a limited extent, such weak ties have also emerged. Residents who are members of these networks are not necessarily connected through friendship or personal relations but are loosely acquainted with each other through an umbrella of common interests (Granovetter 1973). These weak ties have a greater macro-level effect and allow members to innovate by tackling common concerns together.

They include self-help networks, like the chamas—table-banking and merry-go-round networks of women. These terms refer to a group-based funding system not unlike organised unions. Its members make weekly or monthly monetary contributions to create a fund. The members can borrow from this fund. At regular group meetings, issues of poverty and supporting women are addressed, but also fines are paid and defaulters are confronted. The chamas engage in wider socio-economic support activities as well, such as buying property, paying school fees, paying for medical services or covering funeral expenses (community leader, verbal communication, 2019). Interestingly, since these chamas are formed for very specific purposes, they tend to be less ethnically constituted. The key informants pointed out that chamas of women are more common and thus more likely to achieve significant outcomes than chamas of men, which are not as common. The prevalence of chamas of women may be attributed to our survey’s finding that 30% of households are female-headed, that is, by single mothers. Such households might require greater social support from chamas compared to male-headed households with both a father and a mother.

There is also a range of networks of young men who offer services, such as informal electrical connections or garbage collection. Unlike the women’s chamas, these networks are loosely linked based on common self-interest. For example, informal electrical connectors act as individuals in offering their services to about 30 households each. However, when a transformer breaks down, the connectors come together to collect money and get the transformer repaired by qualified engineers, as shown in Fig. 10. Along with the chamas, these networks are examples of weak ties that are not homophilous as they arise out of necessity and are purpose-driven.

Limits of Local Networks and Informality

Although useful in many ways, it is important to highlight that personal networks like those prevailing in Mathare have their limitations. They are time-consuming in terms of their management, social capital depends on the person and is not easily transferable and the number of people that one can trust and with whom social control can be exercised is limited. Furthermore, networks that are mainly based on personal trust and strong ties may have a tendency for social cooperation that leads to social sclerosis (Morgner 2018). By this, we mean a rigidification of social relations that do not just facilitate contact with other people but also may exclude those that are not part of the group of personally trusted members.

When asked about instances in which certain members of the community are excluded, the informants responded that people with disabilities and foreigners tend to be the most excluded, as they often do not have strong social networks. Young single mothers are also not well represented in committees or chamas. In the case of foreigners, migrant Ugandan communities within the settlement are often excluded from accessing certain services because they do not have formal documentation. For example, to access public healthcare services or education, one must provide their national identification or a birth certificate. Foreigners who do not speak Swahili are unable to advocate for their needs or participate in social groups, so they too are isolated. In short, people who generally do not belong to ‘teams’ are easily excluded.

The limits of the network are also visible when it comes to provision of certain services. We observed that services such as water and electricity that are required daily at the household level are based on a division of labour that is controlled and maintained through informal networks of referral. However, other community needs that are acquired at a more individual level, such as healthcare and education, may require more formal enforcement and regulatory frameworks that are beyond the capacity of local networks. Professional certification practices really only work when they are independent of personal networks. They require a far more abstract institutional structure that is typically based on weak ties (Dobrow and Higgins 2005). Similarly, the network is unable to handle other types of professional certificates—for instance, there is a growing trend of unlicensed medical facilities in Nairobi that is currently raising serious concerns for the county government. A report by Nairobi’s County Assembly’s Health Services Committee showed that of 9043 health facilities across the county, only 1079 were licensed to operate (Omulo 2019). According to the key informants, there have been serious cases of medical malpractice in the informal clinics in the settlement, but there is no social network structure that can serve as an independent panel to oversee medical professionalism. In the case of other public issues, such as safety and security, the community mobilisers who act as arbitrators have little capacity or resources to carry out lengthy investigations, prosecutions or enforcement. Furthermore, they are personally invested so independent tribunals or similar structures cannot be facilitated. The focus on strong personal networks inhibits the development of more abstract or independent structures typically associated with professionalism or legal institutions.

Conclusion

Current social frameworks describe social life in informal settlements as disorganised, chaotic and lacking social cohesion. In this paper, we aimed to make a critical examination of these claims, not by simply rejecting them but by piloting theoretical thinking that can help us understand the social life in Mathare from a very different perspective. We used network theory as our theoretical approach but also supplemented the theoretical exercise with some limited empirical evidence based on quantitative surveys, interviews, focus groups and visualisations.

This approach revealed a number of important findings. As shown by the Mathare case, informal settlements in an urban metropolis can reach considerable social complexity through personal networks that organise chains of interactions horizontally and vertically. The strong personal feeling explains why many people feel at home in Mathare. However, in large urban settlements, not every person can be related to the others. Thus, despite the dense structure of the networks and their localised orientation, structural holes emerge. These gaps in the network become opportunities occupied by entrepreneurs and loose associations based on common interests.

Concomitantly, personal networks create certain limits in accessing services for individuals or for the community. Nevertheless, social needs are directly fulfilled and compensated within the network. One only pays for what is directly and immediately needed. As a consequence, there is an almost neo-liberal spirit at work. Financial payment is only offered and only expected when it is part of a direct transaction that serves a purpose for the household and its network. The limits of social control of a personal network mean that the delegation of services becomes difficult to organise in a more abstract way. The personal structure of the network also means that no independent authority exists that can vouch for the legality or quality of services offered. This is problematic in the context of limited healthcare and educational facilities.

In sum, our research paper demonstrates that informal settlements should not be misjudged as being largely atomistic or lacking social cohesion. Recognising the social organisation and, in particular, the social networks of these settlements is key to the success of any intervention. As such, interventions should not simply focus on the provision of physical infrastructure or services. Involving the existing social networks is vital as they hold the power to mobilise participation. To mitigate the limitations of such networks, there is a need to study how they can better connect to the rest of the city.

Change history

07 July 2020

The original version of this article unfortunately contains mistakes introduced during the production phase.

Notes

Within a context of network theory, the term interaction will refer to personalised exchanges within close proximity, whereas relations refer more broadly to different levels (low to high) of interdependence between people within the informal settlement.

References

Aldrich, H. E., & Zimmer, C. (1986). Entrepreneurship through social networks. In D. L. Sexton & R. W. Smiler (Eds.), The art and science of entrepreneurship (pp. 3–23). Cambridge: Ballinger.

Ambole, A., Kaviti Musango, K. J., Buyana, K., Ogot, M., Anditi, C., Mwau, B., Kovacic, Z., Smit, S., Lwasa, S., Nsangi, G., Sseviiri, H., & Brent, C. A. (2019). Mediating household energy transitions through co-design in urban Kenya, Uganda and South Africa. Energy Research & Social Science, 55, 208–217.

Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, M., & Chika Ezeh, A. (2005). A qualitative assessment of support mechanisms in informal settlements of Nairobi. Kenya, Journal of Poverty, 9(3), 89–107.

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (2nd ed.). London: Verso.

Auma, M., & Anyango, J. (2017) “Night of horror as gang raids Mathare slums.” Accessed 10th April 2019: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001251428/night-of-horror-as-gang-raids-mathare-slums

Ayuku, O. D., Kaplan, C., Baars, H., & de Vries, M. (2004). Characteristics and personal social networks of the on-the-street, off-the-street, sheltered and school children in Eldoret, Kenya. International Social Work, 47(3), 293–311.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behaviour. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 350–362.

Burt, R. S. (1992) Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Cambridge; MA: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R. S. (2004). Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), 349–399.

Burt, R. S. (2005). Brokerage and closure: an introduction to social capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cross, J., & Murray, D. (2018). The afterlives of solar power: waste and repair off the grid in Kenya. Energy Research & Social Science, 44, 100–109.

Dobrow, S., & Higgins, M. (2005). Developmental networks and professional identity: a longitudinal study. Career Development International, 10(6/7), 567–583.

Dovey, K. (2012). Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. International Development Planning Review, 34(4), 349–368.

Eisenstadt, S. N. (1961). Anthropological studies of complex societies. Current Anthropology, 2(3), 201–222.

Freeman, L. C. (1979) Centrality in social networks. A conceptual clarification, Social Networks, 1: 215–239.

Gettleman, J. (2006). Accessed 10th April 2019: “Chased by gang violence, residents flee Kenyan slum” https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/10/world/africa/10kenya.html

Ghosh, N., & Goswami, A. (2014). Altruism, social networks, and social capital: some interlinkages. In Sustainability science for social, economic, and environmental development (pp. 33–38). Hershey: IGI Global.

Gould, R., & Fernandez, R. (1989). Structures of mediation: a formal approach to brokerage in transaction networks. Sociological Methodology, 19, 89–126.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Granovetter, M. (1995). Getting a job: a study of contacts and careers (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gutberlet, J., Kain, J. H., Nyakinya, B., Oloko, M., Zapata, P., & Zapata Campos, M. J. (2017). Bridging weak links of solid waste management in informal settlements. The Journal of Environment & Development, 26(1), 106–131.

Harte, W., Hastings, P. A., & Childs, I. R. (2006). Community politics: a factor eroding hazard resilience in a disadvantaged community, Imizamo Yethu, South Africa. In social change in the 21st Century Conference 2006. Brisbane: Carseldine.

Jansen, G. R. M. (1993). Commuting: home sprawl, job sprawl, traffic Jams. In I. Salomon, P. Bovy, & J. P. Orfeuil (Eds.), A billion trips a day. Transportation Research, Economics and Policy (pp. 101–127). Dordrecht: Springer.

Kadushin, C. (2011). Understanding social networks: theories, concepts, and findings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Karekezi, S., Kimani, J., & Onguru, O. (2008). Energy access among the urban poor in Kenya. Energy for Sustainable Development, 12(4), 38–48.

Kassahun, S. (2015). Social capital and trust in slum areas: the case of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Urban Forum, 26(2), 171–185.

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. (1955). Personal influence. New York: Free Press.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Kenya (KNBS). (2019) Kenya Population and Housing Census (KPHC). Kenya: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Kigochie, P. W. (2001). Squatter rehabilitation projects that support home-based enterprises create jobs and housing: the case of Mathare 4A, Nairobi. Cities, 18(4), 223–233.

Kinuthia, M. (1988). Social networks: ethnicity and the informal sector in Nairobi. Working Paper No. 463, Nairobi: Institute of Development Studies, University of Nairobi.

Kovacic, Z., Musango, K. J., Ambole, A., Buyana, K., Smit, S., Anditi, C., Mwau, B., Ogot, M., Lwasa, S., Brent, A. C., Nsangi, G., & Sseviiri, H. (2019). Interrogating differences: a comparative analysis of Africa’s informal settlements. World Development, 122, 614–627.

Kuiper, K. (2012) Slum, Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/slum [accessed March 13, 2020].

Lambe, F., & Senyagwa, J. (2015). Identifying behavioural drivers of cookstove use: a household study in Kibera (p. 6). Nairobi: Stockholm Environment Institute.

Latour, B. (2007). Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laumann, E., Siegel, P., & Hodge, R. W. (1970). The logic of social hierarchies. Chicago: Markham.

Luhmann, N. (1977). Differentiation of society. The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens De Sociologie, 2(1), 29–53.

Mberu, B. U., Ezeh, A. C., Chepngeno-Langat, G., Kimani, J., Oti, S., & Beguy, D. (2013). Family ties and urban–rural linkages among older migrants in Nairobi informal settlements. Population, Space and Place, 19(3), 275–293.

McCulloh, I., Armstrong, H. L., & Johnson, A. N. (2013). Social network analysis with applications. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

McFarlane, C. (2011). Assemblage and critical urbanism. City, 15(2), 204–224.

Meagher, K. (2006). Social capital, social liabilities, and political capital: social networks and informal manufacturing in Nigeria. African Affairs, 105(421), 553–582.

Mollica, K., Gray, B., & Treviño, L. (2003). Racial homophily and its persistence in newcomers’ social networks. Organization Science, 14(2), 123–136.

Morgner, C. (2014). Anti-social behaviour and the London ‘riots’: social meaning-making of the anti-social’. In S. Pickard (Ed.), Anti-social behaviour in Britain: Victorian and contemporary perspectives (pp. 92–101). London: Palgrave.

Morgner, C. (2018). Trust and society: suggestions for further development of Niklas Luhmann’s theory of trust. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 55(2), 232–256.

Morgner, C. (Ed.). (2020). Rethinking relations and social processes: J. Dewey and the notion of ‘trans-action’. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Musalia, J. (2006). Gender, children and family planning networks in Kenya. The Social Science Journal, 43, 167–172.

Muungano Support Trust; Slum Dwellers International (SDI). (2011) University of Nairobi | Dept. of Urban and Regional Planning; University of California, Berkeley | Dept. of City& Regional Planning. Mathare Valley, Nairobi, Kenya 2011 Collaborative Upgrading Plan.

Omulo, C. (2019). “7,900 clinics operating illegally in Nairobi, committee reports” Accessed 29th April 2019: https://mobile.nation.co.ke/counties/nairobi/7900-clinics-operating-illegally-/3112260-5065806-jggesk/index.html

Otieno, W. (2016). “The sad tale of Mathare Valley Slums” https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/ureport/story/2000220296/the-sad-tale-of-mathare-valley-slums. Accessed 07 Oct 2019

Richerson, P. J., & Boyd, R. (1999). Complex societies. Human Nature, 10, 253–289.

Salon, D., & Gulyani, S. (2019). Commuting in urban Kenya: unpacking travel: demand in large and small Kenyan cities. Sustainability, 11(14), 1–22.

Samaio, A. (2018) The new frontlines are in the slums, foreign policy, 7 March, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/03/the-new-frontlines-are-in-the-slums/[accessed 03.02.2020].

Serneels, P. (2007). The nature of unemployment among young men in urban Ethiopia. Review of Development Economics, 11(1), 170–186.

Thomson, S. (2013). Agency as silence and muted voice: the problem-solving networks of unaccompanied young Somali refugee women in Eastleigh. Nairobi, Conflict, Security & Development, 13(5), 589–609.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2003). The challenge of slums. London: Earthscan Publications.

Van Stapele, N. (2010). Maisha bora, kwa nani? A cool life, for whom? Mediations of masculinity, ethnicity, and violence in a Nairobi slum mediations of violence in Africa (pp. 107-140): Brill.

Vidal, J. (2018) The 100 million city: is 21st century urbanisation out of control?, The Guardian, 19 March, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/mar/19/urban-explosion-kinshasa-el-alto-growth-mexico-city-bangalore-lagos[accessed 03.02.2020].

Wellman, B. (1979). The community question: the intimate network of East Yorkers. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 1201–1231.

White, H. C. (1992). Identity and control: a structural theory of social action. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Whyte, W. F. (1943). Street corner society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

The writing of this paper did not receive any specific funding. However, the CoDEC research project referred to in this paper was supported by Leading Integrated Research for Agenda 2030 In Africa (LIRA2030) program from 2017 to 2019. LIRA2030 is a five-year program aimed at supporting collaborative research projects led by early-career researchers across Africa. The program is being implemented by the International Science Council (ISC), in partnership with the Network of African Science Academies (NASAC), with support from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). Additional funding for policy work in Kenya came from the Africa Climate Change Leadership (AfriCLP) program. AfriCLP is managed by University of Nairobi and is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The corresponding author visited Kenya with support from the Leicester Institute of Advanced Studies, University of Leicester, UK. Stellenbosch University Research Office and Stellenbosch University International supported the CoDEC research project with a 2-year Postdoctoral Fellowship and project team mobility exchanges respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morgner, C., Ambole, A., Anditi, C. et al. Exploring the Dynamics of Social Networks in Urban Informal Settlements: the Case of Mathare Valley, Kenya. Urban Forum 31, 489–512 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09389-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09389-2