Abstract

From 2008 to 2018 research across the social sciences has burgeoned concerning sex work and social stigma. This paper employs a scoping review methodology to map scholarship produced during this period and develop a more coherent body of knowledge concerning the relationship between social stigma and female-identified sex workers. Twenty-six pieces of research related to sex work stigma are identified and reviewed from across the disciplines of sociology (n = 8), public health (n = 6), social work (n = 4), criminology (n = 2), psychology (n = 2), communications (n = 2), nursing (n = 1), and political science (n = 1). This scoping review identifies the main sources of sex-work stigma, the ways in which sex-work stigma manifests for sex workers, and stigma resistance strategies, as discussed in this body of literature. If, as theorists and researchers suggest, social stigma is at the foundation of the pernicious violence against sex workers, understanding the sources, manifestations, and resistance strategies of sex-work stigma is critical to countering and shifting this stigma. Findings include potential areas of research, policy, and practice to address and challenge sex-work stigma, recognizing that successful social transformation occurs in a dialectic between society’s socio-structural, community, and intrapersonal levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Female-identified sex workers are commonly ‘othered’ (Sayers 2013; Vanwesenbeeck 2001), stripped of community citizenship (Campbell 2015), and subjected to negative societal labeling (Scambler 2007). Stigma is recognized as the main contributor to the pervasive violence sex workers experience (Lewis et al. 2013; Sanders and Campbell 2007; Seshia 2010; Vanwesenbeeck 2001). Although scholarship on the stigma of sex work is growing, sex-work research has failed to produce a cohesive understanding of the interlocking nature of sex-work stigma sources and stigma manifestations, as well as responsive stigma resistance strategies. Arising from the extant scholarship on stigma and sex work are recent calls to action concerning destigmatization strategies for sex work (Chapkis 2018; Minichiello et al. 2018; Phoenix 2018; Sanders 2018; Weitzer 2018). Responding to this gap, our scoping review asks the question What does the extant body of stigma literature tell us about female-identified sex workers and their experiences of stigma? Accordingly, we aim to: (1) identify the existing body of knowledge concerning sex-work stigma; (2) summarize, analyze, and disseminate current knowledge; and (3) analyze stigma resistance recommendations for future research, policy, and practice. If, as theorists and researchers suggest, social stigma is at the foundation of the pernicious violence against sex workers, understanding the sources, manifestations, and resistance strategies of sex-work stigma is critical to counter and eliminate this stigma.

Defining Sex Work

We define sex work as the exchange of sexual activity for goods or money between two consenting adults (Desyllas 2013; Sloan and Wahab 2000). Sex work exists along a continuum of power, agency, and agreement; at one end, sex work involves individual choice and control of the sexual exchange, while at the opposite end, individual choice and control is absent (British Columbia Coalition of Experiential Communities 2009). Considering this continuum, sex work in this review spans survival sex to sex work undertaken as a preferred source of employment. Sex work within this range is considered sexual exchange free from coercion and with choice, albeit within the constraints of class, gender, race, ability, and other subjectivities.

Sex workers are heterogenous in their identities and experiences but share the commonality of persistent stigma surrounding their employment (Lewis et al. 2013). Linking stigma to violence, Sanders and Campbell (2007) claim that for sex workers to be free from violence, a culture of respect whereby changing the “discourse of disposability” that “incites violence and disrespect towards sex workers” is needed (15). Social stigma, they argue, is the cultural process that fosters disposability and disrespect towards sex workers. Similarly, Lewis et al. (2013) assert that “it is the persistence and pervasiveness of this stigma … that serves to maintain workers’ marginalization and to justify their discriminatory treatment” (200).

Defining Social Stigma

Goffman (1963) originally defined social stigma as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting,” reducing the possessor of the stigmatized attribute “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one’’ (3). Link and Phelan (2001) further theorize that social stigma becomes embedded within the individual and a woman’s outsider status becomes the totalizing lens through which society views her; other facets of sex workers’ identities are consequently erased. This totalizing identity results in stigmatized persons experiencing negative external perceptions and social rejection (Phelan et al. 1997). Corrigan (2004) identified two forms of stigma: public stigma and self-stigma. Public stigma, he proposes, blocks stigmatized individuals from social opportunities, both directly through discrimination and also from self-censorship, such as when the stigmatized individual stops pursuing opportunities or seeking services such as healthcare, due to prior negative experiences. Self-stigma involves the internal process within an individual who internalizes negative social perceptions, creating shame and negatively impacting self-esteem and self-worth (Corrigan 2004). Social stigmas are perpetuated and enforced by social, cultural, economic, and political power (Link and Phelan 2001), serving as a powerful social mechanism to prop-up cultural norms and socially control those who do not adhere to social norms (Scambler 2009). Bowen and Bungay (2016) identify stigma as a process of “othering” that “devalues one’s identity, social contributions, and potentiality in ways that limit how one can interact within one’s world of socio-structural relationships” (187).

Significant deleterious consequences of stigma among various marginalized populations include: social isolation, lower income and employment, and poor physical and mental health (Benoit et al. 2018; Green et al. 2005; Link and Phelan 2001). With its widespread impact on health, wellbeing, and quality of life, Link and Hatzenbuehler (2016) argue that stigma is an essential factor of social inequality. Further, stigma impacts identity creation and social inclusion, as well as access to services, resources, and opportunities (Link and Phelan 1995). Despite these harmful impacts, many stigmatized individuals do not passively accept stigma but seek ways to resist, reduce, and re-frame stigma (Benoit et al. 2018).

Methods

We employed a scoping-review methodology in order to appropriately address and answer the broad research question as the scoping approach provides a deliberate yet exploratory process to locate, identify, and map the body of existing knowledge on a broad topic (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). Scoping reviews are used to quickly identify the core ideas, primary methods, and data of an area of study (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). With this, we followed Arksey and O’Malley (2005) five-step process: (1) generating a search topic; (2) locating relevant studies; (3) including/excluding relevant studies; (4) creating a chart of the data collected; (5) summarizing and reporting the collective data. We created an additional sixth step: discussing implications of the scoping review for future research, policy, and practice directions, as recommended by Levac et al. (2010).

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

To answer our research question, we conducted searches of the following electronic databases: Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX, PsycINFO, Urban Studies Abstracts, PubMed, and Academic Search Complete for English language peer-reviewed articles published between 2008 and January 2019. Search terms, chosen after executing preliminary searches to determine the key-word classifiers most employed among this interdisciplinary body of literature, as well as those which would capture the diversity of forms of sex work, included: sex work, sex worker(s), prostitute(s), prostitution, sex industry, stigma, social stigma, and discrimination.

We limited our search to the past decade as sex-work scholarship has undergone a theoretical shift over that time frame, moving away from radical feminist frameworks of sex work as exploitation and violence (Farley 2004; MacKinnon and Dworkin 1997; Wynter 1987) towards more nuanced understandings of sex work as labour, and research methodologies that privilege the voices and experiences of sex workers (Desyllas 2013; Jeffrey and MacDonald 2011; Sloan and Wahab 2000). We limited our search to five countries—Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States—with arguable cultural similarities. The focus on these nation-states recognizes that stigmas are culturally produced and “structurally mediated cultural objects” (Krüsi et al. 2016, 120), and must be situated and explicated within a similar cultural understanding, while simultaneously recognizing the plurality of individual experiences within the shared context. In addition, we included three articles from a European and International context, as the majority of their data was within the review’s targeted countries.

The time period and country-specific focus also reflects significant changes in sex work legislation. Four of the countries included in this review evaluated or implemented juridical changes governing sex work; the UK has not changed sex-work laws during this time frame. New Zealand decriminalized prostitution in the (2003) Prostitution Reform Act and underwent a subsequent parliamentary review in 2008 (Abel 2011; Prostitution Law Reform Committee 2008). States in Australia also assessed and introduced new sex-work legislation during this period with Western Australia’s (2011) Prostitution Bill and the Australian Capital Territory’s (Australian Capital Territory Government 2018) Sex Work Regulation Act (Australian Capital Territory Government 2018; Government of Western Australia 2011). Bill C-36, the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act, forced Canada to overhaul its sex-work laws after the Supreme Court of Canada ruled Canadian sex work laws violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Government of Canada 2014). Finally, the United States implemented the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) and the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) in 2018, targeting sex trafficking in name but effectively shutting down all forms of online sex-work advertising (United States Congress 2017a, b). These legislative changes signal a need to review and understand sex work in relation to stigma within these jurisdictions.

This scoping review excludes literature regarding sex work and stigma related to HIV/AIDS specifically, as this topic has received considerable attention within sex work literature (e.g. Logie et al. 2011; Scambler and Paoli 2008). Other forms of sex-work stigma remain under-interrogated; Begum et al. (2013) explain that, “despite research suggesting that legal sex work is safe and that emotional risks and social stigma are of greater concern than health risks, much research on sex work has focused on health risks” (1).

Finally, this scoping review uses gender as an inclusion/exclusion criterion, restricting research to female-identified participants. Intersectional theory guides this decision, understanding that multiple aspects of identity and systems of inequity create unique experiences of the world (Marsiglia and Kulis 2009), including social stigma. Thus, this scoping review examines the convergence of female-identity, sex work, and stigma. Cisgender and transgender men’s experiences of sex work and stigma would be another intersection possible for a similar analysis that recognizes the different socio-historical experiences of male sex workers (Minichiello et al. 2018). Other important social categories such as race, class, sexuality, and Indigeneity were not available as inclusion/exclusion criterion as the existing literature is not written in a way that allows parsing out social categories beyond gender.

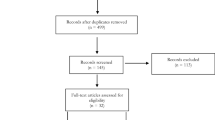

The search yielded 1137 potentially relevant journal articles. After the inclusion criteria was applied to titles and abstracts, and duplicates were removed, 26 articles remained (see Fig. 1). We obtained full texts for the 26 articles and applied the inclusion criteria—the final sample for the scoping review was 26 articles. Between one and four articles were published each year between 2008 and 2018, with most published in 2016 (n = 4).

Results

From the 26 studies included in the review we extracted the author(s), year of publication, purpose, participant characteristics, methodology and methods, country, legal status of sex work, sex-work location typology (outdoor, independent, or managed), and summary of findings, when available (Table 1). Although all of the studies in the review focused on female-identified sex workers, four articles also collected data on a small number of male participants and two included interviews with male brothel staff. Some studies included detailed demographic characteristics such as ethnicity, income, age, relationship status, etc.; however, no research included analysis based on these demographic characteristics.

Most studies were qualitative (n = 21), comprised of structured or semi-structured interviews paired with thematic analysis (n = 13), participant observation (n = 3), interpretive phenomenological analysis (n = 2), content analysis (n = 2), and one each of focus groups, archival research, photo-elicitation, and discourse analysis. Three articles were literature reviews and the two quantitative studies used survey and experimental methodology respectively.

The articles explored the experiences of women across the sex-work spectrum with an almost even distribution of outdoor sex work (n = 11), independent indoor sex work (n = 10), and managed indoor sex work (n = 9). Outdoor location involves sex work performed primarily on the street. Indoor, independent location reflects sex work that is done in various indoor spaces and managed by the sex worker themselves, such as escort or home-based services, while the indoor managed location is associated with sex work organized under the umbrella of a third party, such as brothels or massage parlours.

Most research was conducted in the US (n = 9), followed by Canada (n = 6), Australia (n = 4), New Zealand (n = 1), and the UK (n = 1), and described a range of juridical contexts: partially criminalized/Nordic (n = 8), criminalized (n = 7), legalized (n = 6), and decriminalized (n = 1) (Table 2).

Thematic analysis of the articles revealed three interconnected components of sex-work stigma: (1) sources of sex-work stigma (n = 18); (2) manifestations of social stigma experienced by sex workers (n = 20); and (3) sex-work stigma resistance strategies (n = 17). While we characterize these three themes as discrete concepts, in reality, each of the three themes is interspersed across articles, and each article offers explanation of at least one, but sometimes all of the three themes we identified.

Sources of Sex-Work Stigma

Sex-work stigma presented as a complex process involves layers replicated through social structures, institutions, community organizations, and individuals working to enforce social norms (see Fig. 2). Stigma is centered on maintaining social order by advancing the concerns of groups and individuals possessing the most power as well as justifying these differences by “convincing the dominated to accept existing hierarchies through processes of hegemony” (Parker and Aggleton 2003, 6) and—in this way—preserves the hierarchies that perpetuate it. Similarly, Bowen and Bungay (2016) note that power structures communicate and create the social process of stigma as dominant groups wield stigma as a means of electing, dictating, and strengthening their model of how people should behave in the world. Thus, the socio-power structures that preserve hierarchical domination placing female-identified sex workers in a marginalized position are also the structural roots of sex-work stigma.

According to studies in the review, gender, race, class, colonialism, ableism, and capitalism serve as interlocking hierarchical social structures that contribute to sex-work stigma and highlight its structural nature. Although these socio-structural systems are the base of sex-work stigma, sex-work discourses in media, academia, and the state emphasize sex workers’ individual responsibility and behaviour (Strega et al. 2014; Weitzer 2018). These discourses obfuscate socio-structural systems’ responsibility in creating the institutional conditions necessary for the social process of stigma (Hallgrímsdóttir et al. 2008; Young 2011).

Gender, particularly ideas of female sexuality, is the most heavily recognized socio-structural source of sex-work stigma, as female-identified sex workers embody a “resistant identity that exposes suppression of women’s sexuality” (Jeffrey and MacDonald 2011, 11). Supporting this argument, a Canadian study of print media coverage of sex work concluded that sex workers were consistently depicted as women overcome by sexual depravity and enslaved into immoral behavior (Hallgrímsdóttir et al. 2008). This analysis also exposed a consistent fusion between sex work and female sexuality, while male sexuality, as clients or sex workers, was ignored (Hallgrímsdóttir et al. 2008). Murphy et al. (2015) research with sex workers in romantic personal relationships also illuminated the impact of gender on sex work. In order to reduce guilt experienced by transgressing traditional female relationship roles involving commitment and faithfulness, sex workers in their study distanced themselves emotionally from clients and avoided physical pleasure in their work. Similarly, Koken’s (2013) research with online escorts in the U.S. exposes sex workers’ dichotomous position in a social context that both vilifies and rewards women for engaging in sexual behavior that transgresses heteropatriarchal relationship norms. Gender, in concert with other hierarchical social systems, creates and perpetuates the institutions that regulate society.

Articles in this review documented institutional sources of sex-work stigma across multiple systems (government, legal, academia, media, healthcare, and financial). Although criminalized, partially criminalized/Nordic, and legalized juridical contexts were all shown to perpetuate sex-work stigma, the form of regulation influences the amount of vulnerability and marginalization sex workers experience within healthcare systems (Sanders 2016). For example, criminalized and partially-criminalized legal environments perpetuate sex-work stigma to a greater degree. However, within legalized environments, the movements and health status of sex workers are monitored (Ham and Gerard 2014) and sex workers in legal brothels in Nevada are subject to the practice of “lockdown,” whereby they must remain in-brothel for the duration of their contract as well as undergo state-regulated health checks (Blithe and Wolfe 2017). Health monitoring fosters the belief that sex workers are carriers of disease and exposes women as sex workers, which hinders their ability to leave sex work and impedes their access to financial services (Begum et al. 2013; Ham and Gerard 2014). Relatedly, according to the articles in this review, healthcare was significantly intertwined with stigma; other research advances that non-judgemental and sensitive healthcare systems and providers are required to counter sex-work stigma (Lazarus et al. 2012).

In terms of stigma within financial systems, legal brothel workers in Nevada report being denied financial loans as well as access to accounting and financial planning services (Blithe and Wolfe 2017). Sex workers in Australia also report stigma when attempting to access financial services (Huang 2016; Begum et al. 2013).

Police were found to perpetuate stigma by treating outdoor sex workers in Canada as a threat to neighborhood values, pushing sex workers out of communities and into isolated industrial zones (Krüsi et al. 2016). The criminalized environment frames sex workers as criminals without legal protection and as neighborhood interlopers. Criminalized contexts also expose sex workers to stigma from the criminal justice system (Sallmann 2010).

The media is another socio-structural source of stigma. Strega et al. (2014) concluded that Canadian media portrays sex workers as either vermin or victims: partaking in risky lifestyles that threaten children. Another Canadian media study presented similar findings, illustrating how newspapers constructed sex-work stigma through narratives depicting sex workers as enslaved, contagious, and risky (Hallgrímsdóttir et al. 2008). Concerningly, prior academic literature on sex work is noted as stigmatizing, specifically the radical feminist scholarship of the 1980s and 1990s that framed sex work as exploitative and inherently violent (Desyllas 2013; Sanders 2016; Weitzer 2018).

Stigma Manifestation

In addition to the socio-structural sources of stigma outlined above, sex workers report experiencing discrimination and negative labeling from family, friends, community, and clients, as a consequence of stigma (Begum et al. 2013; Sallmann 2010). Social exclusion impacts sex workers’ access to healthcare (Lazarus et al. 2012), support services (Oselin 2010; Tomura 2009), and various forms of employment (Begum et al. 2013). These effects result in sex workers enduring social and spatial isolation (Reeve 2013; Sanders 2016), as well as unsafe working environments (Benoit et al. 2018).

These many manifestations of stigma result in experiences of shame and fear (Bowen and Bungay 2016; Reeve 2013), prevent sex workers from living authentically (Levey and Pinsky 2015; Murphy et al. 2015; Wolfe and Blithe 2015), and impede physical and mental wellness (Benoit et al. 2018). Collectively, the literature in this review affirms that sex workers experience public embarrassment, estrangement from family, friends, and community, state monitoring, and police harassment. Once internalized, this self-stigma creates and perpetuates feelings of shame and lack of worth, exacerbating social isolation and further impeding wellness.

The most heavily cited impact of sex-work stigma in this review, is interpersonal violence (Krüsi et al. 2016; Sanders 2016; Sallmann 2010; Strega et al. 2014). Stigma creates a culture that normalizes violence against sex workers, rendering them vulnerable to violence. Many sex workers identify stigma as intertwined with pervasive beliefs that sex workers are personally to blame or deserve the violence and discrimination they experience (Sallmann 2010). Similarly, dominant narratives that frame sex work as a high-risk lifestyle bolster stigma through normalizing violence against sex workers (Strega et al. 2014). The prevalence of these beliefs is illustrated in experimental research on sex-work stigma that demonstrates significantly higher levels of victim blaming and less empathy towards sex workers who experienced sexual assault than women not tainted with a sex worker identity (Sprankle et al. 2018). These views infiltrate institutional agents as evident in police responses to sex workers, which view violence as a common part of sex work (Krüsi et al. 2016). Similarly, sex workers in Canada describe sex-work stigma as motivating the violence they experience: viewed as less-than-human and amoral, violence is both expected and deserved (Seshia 2010). Further, laws directed at reducing the visibility of sex work, such as prohibitions surrounding communicating in public for the purpose of solicitation, render sex workers vulnerable to violence due to spatial isolation (Krüsi et al. 2016; Sanders 2016). Ultimately, sex-work stigma facilitates an environment wherein sex workers are framed as disposable and culpable for the violence they experience.

Stigma Resistance

In the face of these rampant sources and manifestations of sex-work stigma, sex workers and sex work allies draw from a variety of stigma resistance strategies on the structural, community, and individual level. Structural resistance strategies involve the decriminalization of sex work (Abel 2011; Bowen and Bungay 2016) and treating crimes against sex workers as a hate crime (Sanders 2016). Educational resistance strategies aim to increase public awareness and include education that frames sex work as labor (Bowen and Bungay 2016), or consciousness-raising media campaigns such as advertising slogans proclaiming “someone you know is a sex worker” (Schreiber 2015 as cited in Weitzer 2018, 724). Education targeted towards sex workers as stigma resistance includes legal and financial navigation and enhancing knowledge (Huang 2016; Oselin 2010). Peer support was also identified as a resistance strategy, in the form of sex work communities (Huang 2016) and sex work positive business networks (Blithe and Wolfe 2017). Social service agencies that provide non-judgemental services are also critical for resisting sex-work stigma (Desyllas 2013; Huang 2016), as is community-based collective action by sex work advocacy groups (Benoit et al. 2018).

On an individual level, sex workers employ a variety of strategies to counter and distance themselves from stigma, including keeping their personal and professional lives “bodily, geographically, and symbolically” distant (Reeve 2013, 828). One means of creating this separation is by viewing sex work as a performance, demarcating a clear boundary between work and private life (Abel 2011). Constructing a division between personal and professional realms is not unique to sex work as other service industry workers routinely disengage their inner-selves from their work (Abel 2011); however, it is less clear as to whether this separation is beneficial or detrimental (Abel 2011; Koken 2012; Weitzer 2018). Another means of creating distance from sex-work stigma is selectively disclosing employment, which is identified as a means of exerting power over information (Ham and Gerard 2014) and as a coping and avoidance mechanism that may create social isolation from living a double life (Begum et al. 2013; Koken 2012; Levey and Pinsky 2015). Non-disclosure of employment status is particularly challenging for outdoor sex workers who experience increased public visibility due to their work environment (Abel 2011). Sex workers with experiences of homelessness and substance use reported that stigma from these sources was easier to manage than sex work stigma (Reeve 2013; Sallmann 2010).

To resist stigma, sex workers actively re-frame sex work. By countering the dominant discourses perpetuating stigma, sex workers highlight the positive aspects of sex work (Levey and Pinsky 2015), reject double standards of female sexuality (Sallmann 2010), and identify how their personal values align with sex work (Tomura 2009). Desyllas’ (2013) study found that reframing and defining sex work through the production of art counters sex-work stigma. Levey and Pinsky (2015) concluded that creating narratives of resistance allows sex workers to “transform or subvert dominant ideologies and discourses of power and social control” (363). These narratives then reverberate through and shift socio-structural systems by challenging social beliefs and practices as well as providing alternative portrayals of sex work. In these ways, sex workers use narratives of resistance as a successful means of rejecting the labels and judgements social stigma attempts to impose, and separate themselves from sex-work stigma.

Discussion

Understanding the multi-faceted nature of sex-work stigma is key to changing stigma, as the nature of oppression must be understood and revealed to create the basis for transformative social change (Bishop 2015; Mullaly 2007). This scoping review identifies the main sources of sex-work stigma, the ways in which sex-work stigma manifests for sex workers, and stigma resistance strategies. Potential areas of research, policy, and practice to address and challenge sex-work stigma emerged through this review, recognizing that successful social transformation occurs in a dialectic between socio-structural, community, and intrapersonal levels (Mullaly 2007).

Recommendations for Future Research

Sanders (2016) asserts that the same structural conditions that create sex-work stigma possess pathways towards solutions. If these socio-structural powers and hierarchies possess much of the responsibility for sex-work stigma, it becomes even more important to understand how the experience and manifestations of stigma impact sex workers with various subjectivities. Conflating sex workers across the spectrum as a homogenous group is a limitation of current research on sex work and stigma. Sex workers, like all of us, possess “multiple realities and complex selves” (Desyllas 2014, 497); thus, sex work and stigma research would necessarily benefit from an intersectional lens that addresses a multiplicity of experiences in relation to socio-power structures. For example, an intersectional understanding of sex work research and stigma is key when considering the experiences of many outdoor sex workers in Canada who “belong to a space of prostitution and Aboriginality in which violence routinely occurs” (Razack 2000, 125). Research in Canada’s Vancouver Downtown Eastside (DTES) shows that sex work reflects structural issues of colonization as approximately 70% of sex workers in the DTES are Indigenous (Culhane 2003; Krüsi et al. 2012) and “the dominant image of the DTES is that of an Indigenous sex worker” (Hunt 2013, 97). Sex workers in other jurisdictions experience similar intersections of subjectivity yet, despite widespread understanding that complex socio-structural issues create the environment of stigma, sex work and stigma research struggles to create an intersectional understanding that takes into account the role of colonialism. Seshia’s (2010) research with street-based sex workers in Winnipeg, Canada, is the lone exemption that highlights the link between sex-work stigma and colonial violence. Chapkis (2018) argues that ending sex work stigma requires confronting patriarchy, racism, classism, and oppressions targeting sexual differences, dismantling the social categories of “normal” and “perverse” (p. 745). Accordingly, further research that aims to unfold the intersections of social locations within sex workers’ lived experiences is both novel and necessary in relation to stigma.

To understand how converging axes of oppression form unique experiences of sex work and stigma, scholarship requires methodological approaches that expand beyond traditional sit-down interviews, which methodologically dominate the field. Arts-based research methods (Grittner 2019; Desyllas 2014), as well as other decolonizing methods such as storytelling (Qwul’sih’yah’maht 2005; Wilson 2008) are shown to create space for both researchers and research participants to reflect, acknowledge, and understand the power relations intertwined within identity and lived experience. Towards this goal, Rogers (2012) advocates for anti-oppressive research methods that: “connect with people in a collaborative way, identifying issues as well as exposing oppression and joining with people to challenge it and instigate change” (13). Experiences of intersectionality and identity are often difficult to express verbally but the reflexive mental space embedded within these methodological forms provide alternatives for exploring experiences and ideas (Gauntlett and Holzwarth 2006), offering potent possibilities for understanding intersectional experiences of sex work and stigma.

Recommendations for Policy

Social stigma was found across all juridical environments, suggesting that while legal systems play a role in contributing to or exacerbating stigma, they are not solely responsible for sex-work stigma; as Weitzer (2018) observes: “decriminalization is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for destigmatization” (722). Without decriminalization sex work stigma remains entrenched as sex workers are framed by the state, law enforcement, and media as community outsiders associated with criminal activity (Sanders 2018). Stigma can only be effectively targeted via policy once sex workers possess the rights of full citizenship.

Any policy changes, however, should be based on the lived experience of sex workers and generated from “collaboration, trust and critical reflection” in partnership with sex workers (Minichiello et al. 2018, 734). As this scoping review illustrates, with 21 of 26 articles epistemologically grounded in qualitative research that privileges the knowledge and voices of women working in the sex industry, sex workers possess much of the knowledge required to combat sex-work stigma and improve their social position, but their knowledge is slow to infiltrate public policy. Regulatory frameworks developed in this void that ignore the voices of sex workers will “continue to produce contradictory outcomes and unintended harms” (Ham and Gerard 2014, 310).

Current sex trafficking policies are exemplars of unintended consequences and damage stemming from legislation. The current policy realm in many of the countries included in this scoping review [e.g. the United States’ (2018) Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) and the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA)] foster sex work stigma by framing all sex work as exploitative and by conflating sex work and sex trafficking (Weitzer 2007). Activists from religious, conservative, and radical feminist groups drive this discourse, while sex workers’ perspectives remain overlooked (Weitzer 2007, 2014; Bettio et al. 2017). New policy directions that recognize sex work’s “continuum of choice” (Bettio et al. 2017, 17) will promote a more nuanced understanding of agency while concomitantly decreasing sex work stigma, which Bettio et al. (2017) argue are inversely related.

An example of successful policy that is based on the expertise of sex workers, in coalition with sex work support agencies and law enforcement, exists in Merseyside, UK (Sanders 2016). Implemented in 2006, the Merseyside policy enforces crimes against sex workers as hate crimes, which increased reports of violence to the police by 400% over the first four years it was implemented and resulted in a conviction rate of 83% (Sanders 2016). Merseyside’s example illustrates that successful sex-work policy is predicated upon the lived experiences of sex workers.

Recommendations for Practice

Education about sex work aimed at consciousness-raising among the general public is a potentially fruitful avenue for countering sex-work stigma. Widespread public education campaigns that challenge dominant discourses about sex work can act as a corrective frame, positioning sex workers as rightful members of a community (Bowen and Bungay 2016). Further, sex-worker advocacy and collective action (Benoit et al. 2018), community engagement practices (Wolfe and Blithe 2015), and public education undertaken by former sex workers (Bowen and Bungay 2016) are key stigma resistance strategies.

Education and consciousness-raising amongst sex workers is also shown to resist internalized stigma. Social-support agencies have an important role to play in this work by providing non-judgemental programming and services to sex workers. Intrapersonal support that works with sex workers to recognize, reflect on, and critique the structural and social causes of their experiences of stigma and then actively reconstruct their work and identity is a successful practice intervention (Desyllas 2014; Huang 2016; Levey and Pinsky 2015; Wolfe and Blithe 2015). Sex workers identified peer support groups as a particularly impactful means of achieving this intrapersonal work. For example, in Huang’s (2016) research, over a third of participants emphasized the importance of peer support in resisting stigma. Specific knowledge and skill-building education is also important. Programming that provides financial planning and income tax guidance would allow sex workers to navigate through murky economic space and assist in creating financially stable and non-economically marginalized futures (Blithe and Wolfe 2017; Huang 2016). Huang’s (2016) research also identifies that support agencies must treat sex work as a form of labor, practice empathy, and treat sex workers as equals.

Conclusion

This scoping review identifies the recent body of research shaping understanding surrounding the sources of sex-work stigma, the manifestations of sex-work stigma, and stigma resistance strategies from across a variety of disciplines. While sex-work stigma research is relatively plentiful and increasing in recent years, possibly indicating a growing understanding of the critical connection between sex work and social stigma, interventions to counter sex-work stigma remain largely absent within policy and practice domains. Critically, sex workers continue to live under the burden of stigma, while policy and practice have historically remained mired in debates of criminalization versus legalization and exploitation versus emancipation. This review underscores the requirement for comprehensive policy changes and social support programs for sex workers that address stigma, rooted in the lived experience and knowledge of sex workers. A pressing need remains for promising research, policy, and practice avenues aimed at preventing sex-work stigma from destroying “sex workers from the inside out and from the outside in” (Bowen and Bungay 2016, 195).

References

*Denotes reference included in scoping review

*Abel, G. M. (2011). Different stage, different performance: The protective strategy of role play on emotional health in sex work. Social Science and Medicine, 72(7), 1177–1184.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

Australian Capital Territory Government. (2018). Sex work regulation act. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/DownloadFile/sl/2018-15/current/PDF/2018-15.PDF.

*Begum, S., Hocking, J. S., Groves, J., Fairley, C. K., & Keogh, L. A. (2013). Sex workers talk about sex work: Six contradictory characteristics of legalised sex work in Melbourne, Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(1), 85–100.

*Benoit, C., Jansson, S. M., Smith, M., & Flagg, J. (2018). Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 457–471.

Bettio, F., Della Giusta, M., & Di Tommaso, M. L. (2017). Sex work and trafficking: Moving beyond dichotomies. Feminist Economics, 23(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2017.1330547.

Bishop, A. (2015). Becoming an ally: Breaking the cycle of oppression in people. London: Zed Books.

*Blithe, S. J., & Wolfe, A. W. (2017). Work-life management in legal prostitution: Stigma and lockdown in Nevada’s brothels. Human Relations, 70(6), 725–750.

*Bowen, R., & Bungay, V. (2016). Taint: An examination of the lived experiences of stigma and its lingering effects for eight sex industry experts. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(18), 186–199. (Personality Traits & Processes [3120]).

British Columbia Coalition of Experiential Communities (BCCEC). (2009). Continuum of sexual exchange. Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from http://www.catie.ca/en/pc/program/shift.

Campbell, A. (2015). Sex work’s governance: Stuff and nuisance. Feminist Legal Studies, 23(1), 27–45.

Chapkis, W. (2018). Commentary: Response to Weitzer ‘Resistance to sex work stigma’. Sexualities, 21(5–6), 743–746.

Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614.

Culhane, D. (2003). Their spirits live within us: Aboriginal women in Downtown Eastside Vancouver emerging into visibility. American Indian Quarterly, 27(3/4), 593–606.

Desyllas, M. C. (2013). Representations of sex workers’ needs and aspirations: A case for arts-based research. Sexualities, 16(7), 772–787.

*Desyllas, M. C. (2014). Using photovoice with sex workers: The power of art, agency and resistance. Qualitative Social Work, 13(4), 477–501.

Farley, M. (2004). “Bad for the body, bad for the heart”: Prostitution harms women even if legalized or decriminalized. Violence Against Women, 10(10), 1087–1125.

Gauntlett, D., & Holzwarth, P. (2006). Creative and visual methods for exploring identities. Visual Studies, 21(1), 82–91.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on a spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Government of Canada. (2014). Technical paper: Bill C-36, protection of communities and exploited persons act. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from http://www.justice.gc.ca/Eng/Rp-Pr/Other-Autre/Protect/P1.Html.

Government of Western Australia. (2011). Prostitution bill. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/bills.nsf/AB39DEA43DCCB5084825793D001C7937/$File/Bill+218-1.pdf.

Green, S., Davis, C., Karshmer, E., Marsh, P., & Straight, B. (2005). Living stigma: The impact of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in the lives of individuals with disabilities and their families. Sociological Inquiry, 75(2), 197–215.

Grittner, A. L. (2019). The Victoria Mxenge: Gendered formalizing housing and community design strategies out of Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 34(2), 599–618.

*Hallgrímsdóttir, H. K., Phillips, R., Benoit, C., & Walby, K. (2008). Sporting girls, streetwalkers, and inmates of houses of ill repute: Media narratives and the historical mutability of prostitution stigmas. Sociological Perspectives, 51(1), 119–138.

*Ham, J., & Gerard, A. (2014). Strategic in/visibility: Does agency make sex workers invisible? Criminology & Criminal Justice: An International Journal, 14(3), 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895813500154.

*Huang, A. L. (2016). De-stigmatizing sex work: Building knowledge for social work. Social Work & Social Sciences Review, 18(1), 83–96.

Hunt, S. (2013). Decolonizing sex work: Developing an intersectional Indigenous approach. In E. van der Meulen, E. M. Durisin, & V. Love (Eds.), Selling sex: Experience, advocacy, and research on sex work in Canada (pp. 82–100). Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

Jeffrey, L. A., & MacDonald, G. (2011). Sex workers in the Maritimes talk back. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

*Koken, J. (2012). Independent female escort’s strategies for coping with sex work related stigma. Sexuality and Culture, 16(3), 209–229.

*Krüsi, A., Kerr, T., Taylor, C., Rhodes, T., & Shannon, K. (2016). “They won’t change it back in their heads that we’re trash”: The intersection of sex work-related stigma and evolving policing strategies. Sociology of Health & Illness, 38(7), 1137–1150.

*Lazarus, L., Deering, K. N., Nabess, R., Gibson, K., Tyndall, M. W., & Shannon, K. (2012). Occupational stigma as a primary barrier to health care for street-based sex workers in Canada. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(2), 139–150.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69.

*Levey, T. G., & Pinsky, D. (2015). A constellation of stigmas: Intersectional stigma management and the professional dominatrix. Deviant Behavior, 36, 347–367. (Industrial & Organizational Psychology [3600]).

Lewis, J., Shaver, F., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2013). Going ‘round again: The persistence of prostitution-related stigma. In E. van der Meulen, E. M. Durisin, & V. Love (Eds.), Selling sex: Experience, advocacy, and research on sex work in Canada (pp. 198–208). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

*Lindemann, D. J. (2013). Health discourse and within-group stigma in professional BDSM. Social Science and Medicine, 99, 169–175.

Link, B., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2016). Stigma as an unrecognized determinant of population health: Research and policy implications. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 41(4), 653–673.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Spec No, 80–94.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385.

Logie, C. H., James, L., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. R. (2011). HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: A qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS medicine, 8(11), e1001124.

MacKinnon, C. A., & Dworkin, A. (Eds.). (1997). In harm’s way: The pornography civil rights hearings. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Marsiglia, F., & Kulis, S. (2009). Diversity, oppression, and change: Culturally grounded social work. Chicago: Lyceum Books.

Minichiello, V., Scott, J., & Cox, C. (2018). Commentary: Reversing the agenda of sex work stigmatization and criminalization: Signs of a progressive society. Sexualities, 21(5–6), 730–735.

Mullaly, R. P. (2007). The new structural social work. Oxford University Press.

*Murphy, H., Dunk-West, P., & Chonody, J. (2015). Emotion work and the management of stigma in female sex workers’ long-term intimate relationships. Journal of Sociology, 51(4), 1103–1116.

*Oselin, S. (2010). Weighing the consequences of a deviant career: Factors leading to an exit from prostitution. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 527–549.

Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 13–24.

Phelan, J., Link, B. G., Moore, R. E., & Stueve, A. (1997). The stigma of homelessness: The impact of the label “homeless” on attitudes toward poor persons. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60, 323–337.

Phoenix, J. (2018). A commentary: Response to Weitzer ‘Resistance to sex work stigma’. Sexualities, 21(5–6), 740–742.

Prostitution Law Reform Committee. (2008). Report of the prostitution law review committee on the operation of the prostitution reform act 2003. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Justice, Government of New Zealand. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from http://prostitutescollective.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/report-of-the-nz-prostitution-law-committee-2008.pdf.

Qwul’sih’yah’maht (Thomas, R. A.). (2005). Honoring the oral traditions of my ancestors through storytelling. In L. Brown & S. Strega (Eds.), Research as resistance: Critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches (pp. 237–254). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Razack, S. H. (2000). Gendered racial violence and spatialized justice: The murder Pamela George. Canadian Journal of Law & Society/La Revue Canadienne Droit et Société, 15(2), 91–130.

*Reeve, K. (2013). The morality of the “immoral”: The case of homeless, drug-using street prostitutes. Deviant Behavior, 34(10), 824–840.

Rogers, J. (2012). Anti-oppressive social work research: Reflections on power in the creation of knowledge. Social Work Education, 31(7), 866–879.

*Sallmann, J. (2010). Living with stigma: Women’s experiences of prostitution and substance use. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 25(2), 146–159.

*Sanders, T. (2016). Inevitably violent? Dynamics of space, governance, and stigma in understanding violence against sex workers. Studies in Law, Politics & Society, 71, 93–114.

Sanders, T. (2018). Unpacking the process of destigmatization of sex work/ers: Response to Weitzer ‘Resistance to sex work stigma’. Sexualities, 21(5–6), 736–739.

Sanders, T., & Campbell, R. (2007). Designing out vulnerability, building in respect: Violence, safety and sex work policy. The British Journal of Sociology, 58(1), 1–19.

Sayers, N. (2013). Social spaces and #SexWork: An essay [Blog post]. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from https://kwetoday.com/2013/12/18/social-spaces-and-sexwork-an-essay/.

Scambler, G. (2007). Sex work stigma: Opportunist migrants in London. Sociology, 41(6), 1079–1096.

Scambler, G. (2009). Health-related stigma. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31(3), 441–455.

Scambler, G., & Paoli, F. (2008). Health work, female sex workers and HIV/AIDS: Global and local dimensions of stigma and deviance as barriers to effective interventions. Social Science and Medicine, 66(8), 1848–1862.

Schreiber, R. (2015). ‘Someone you know is a sex worker’: A media campaign for the St. James Infirmary. In M. Laing, K. Pilcher, & N. Smith (Eds.), Queer sex work (pp. 255–262). London: Routledge.

*Seshia, M. (2010). Naming systemic violence in Winnipeg’s street sex trade. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 19(1), 1–17.

Sloan, L., & Wahab, S. (2000). Feminist voices on sex work: Implications for social work. Affilia, 15(4), 457–479.

*Sprankle, E., Bloomquist, K., Butcher, C., Gleason, N., & Schaefer, Z. (2018). The role of sex work stigma in victim blaming and empathy of sexual assault survivors. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(3), 242–248.

*Strega, S., Janzen, C., Morgan, J., Brown, L., Thomas, R., & Carriére, J. (2014). Never innocent victims: Street sex workers in Canadian print media. Violence Against Women, 20(1), 6–25.

*Tomura, M. (2009). A prostitute’s lived experiences of stigma. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 40(1), 51–84.

United States Congress. (2017a). Allow states and victims to fight online sex trafficking act of 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1865.

United States Congress. (2017b). Stop enabling sex traffickers act of 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1693.

Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2001). Another decade of social scientific work on sex work: A review of research 1990–2000. Annual Review of Sex Research, 12(1), 242–289.

Weitzer, R. (2007). The social construction of sex trafficking: Ideology and institutionalization of a moral crusade. Politics & Society, 35(3), 447–475.

Weitzer, R. (2014). New directions in research on human trafficking. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 653(1), 6–24.

*Weitzer, R. (2018). Resistance to sex work stigma. Sexualities, 21(5–6), 717–729.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

*Wolfe, A. W., & Blithe, S. J. (2015). Managing image in a core-stigmatized organization: Concealment and revelation in Nevada’s legal brothels. Management Communication Quarterly, 29, 539–563. (Organizational Behavior [3660]).

Wynter, S. (1987). Whisper: Women hurt in systems of prostitution engaged in revolt. In E. Delacoste, F. (Ed.), Sex work: Writings by women in the sex industry (pp. 266–270). Jersey City, NJ: Cleis Press.

Young, I. M. (2011). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the assigned editor and the reviewers for their thoughtful feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grittner, A.L., Walsh, C.A. The Role of Social Stigma in the Lives of Female-Identified Sex Workers: A Scoping Review. Sexuality & Culture 24, 1653–1682 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09707-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09707-7