Abstract

This paper presents a review of the key Australian legislation passed between 2009 and 2019 targeting outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGs). It identifies the key similarities and differences across the reforms and provides examples of the legislation being used to disrupt serious and organised crime activity by OMCGs. It also presents some of the barriers to effective enforcement of the legislation. There is limited information about the use and effectiveness of the legislation. The paper considers some of the objections raised in respect of these measures and suggests future directions for responding to OMCG-related crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Criminal laws in Australia operate on a hybrid federal, state and territory model. Most criminal laws are set by the six states (in descending order of population, these are New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (Vic), Queensland (Qld), South Australia (SA), Western Australia (WA) and Tasmania (Tas) and two territories (the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Northern Territory (NT). There are also Commonwealth (Cth) (or federal) criminal laws, but these are very limited in scope, with federal crimes accounting for only 2% of all offences (see eg Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020; see generally Odgers 2019). As a result, most criminal laws are introduced on a jurisdictional basis, although there have been some attempts at a nationally consistent approach, especially through the work of the Council of Attorneys-General (2020).

As detailed by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) (see Bartels 2009, b; see also Bartels 2010a, c), from 2000 onwards, most Australian states and territories passed a range of legislative measures designed to disrupt the activities of outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGs). The principal measures included introducing (and expanding):

-

specific offences by criminal organisations (eg Crimes Legislation Amendment (Gangs) Act 2006 (NSW);

-

‘control orders’ against specifically ‘declared’ organisations (see Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Act 2008 (SA); Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2009 (NSW); Serious Crime Control Act 2009 (NT); Criminal Organisation Act 2009 (Qld));

-

anti-fortification laws, to enable law enforcement to prevent the installation of or remove any fortification of OMCG clubhouses (see Criminal Investigation (Exceptional Powers) and Fortification Removal Act 2002 (WA); Statutes Amendment (Anti-Fortification) Act 2003 (SA); Police Offences Amendment Act 2007 (Tas)); and

-

police and intelligence-gathering powers (eg, Crimes (Assumed Identities) Act 2004 (Vic); Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2004 (Vic); Major Crimes (Investigative Powers) Act 2004 (Vic); Surveillance Devices (Amendment) Act 2004 (Vic).

Early 2009 saw several ‘bikie gang violence’ (ABC News 2009) incidents across Australia. A key event during this period was a ‘“ferocious and vicious” bikie brawl’ (AAP 2010; see also ABC News 2009; Bartels 2010b) between members of the Hells Angels and Comancheros at Sydney airport in 2009, resulting in the death of the brother of a Hells Angel member. There has since been a further flurry of amending and new legislation introduced around Australia in response to OMCGs. As a result, this paper updates Bartels’ (2009, 2010b) legislative analyses and presents a review of the relevant legislation passed between 2009 and 2019 (the review period). The paper identifies the key similarities and differences across the reforms and examples of the legislation being used to disrupt serious and organised crime activity by OMCGs.

There has also been significant academic commentary on these developments, with the focus often centring on the extent to which the laws impede civil rights and impact on marginalised groups, such as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, who are over-represented in the Australian criminal justice system, but are not the articulated subjects of the relevant legislation. However, commentators have also observed benefits from some of the reforms. This paper offers an overview of key findings and points of discussion emerging from the literature over the survey period. It also presents some of the barriers to effective enforcement of the legislation, including legal challenges, the complexity and resource implications of the new frameworks and suggestions that there have been limited and inappropriate use of the new powers.

Recent Australian legislation targeting OMCGs

To identify relevant legislation, we undertook a systematic search of legal databases (see Appendix Table 2 for the key legislation passed in the review period, by jurisdiction and year). Research on the impact of this legislation was identified through a comprehensive search of key databases and review of peer-reviewed grey literature and media reports. The search terms included ‘OMCG*’, ‘outlaw motorcycle gang*’, ‘gang*’, ‘bikie*’, ‘consorting’, ‘Rebel*’ and ‘Comanchero*.

While the previous review period surveyed by Bartels (2010b) was undoubtedly active, with the introduction of 19 pieces of legislation aimed at curtailing the activities of OMCGs, the 10-year period from 2009 to 2019 saw a considerable increase in laws both explicitly and implicitly directed towards the regulation of OMCGs, with 79 individual pieces of legislation enacted. With the exception of Western Australia and the Northern Territory, which passed only three and four Acts respectively, all jurisdictions passed signification amounts of legislation during this period. The most legislatively active jurisdictions were NSW (16 Acts) and the Commonwealth (Cth) (11 Acts), while Queensland, South Australia and Victoria each passed 10 Acts.

The rationales for the reforms were varied. For example, the then ACT Attorney-General explained that the Crimes (Assumed Identities) Act 2009 (ACT) was designed to ‘enhance the ability of the police to involve themselves covertly in organised crime, under strict operational control, to gain evidence and intelligence about criminal behaviour’ (Corbell 2010: 3422), while the amendments in the Crimes (Serious and Organised Crime) Legislation Amendment Act 2016 (ACT) purported to ‘give ACT Policing and the justice system enhanced capabilities to prevent and target crime at an individual level, where it has been proven most effective and disruptive to criminal OMCG activity’ (Corbell 2016). The intention of the Migration Amendment (Character and General Visa Cancellation) Act 2014 (Cth) was ‘to lower the threshold of evidence required to show that a person who is a member of a criminal group or organisation, such as a criminal motorcycle gang… does not pass the [migration] character test’ (Commonwealth of Australia 2014).

The objectives of the Crimes (Serious Crime Prevention Orders) Act 2016 (NSW) and Crimes Legislation Amendment (Organised Crime and Public Safety) Act 2016 (NSW) included restricting the activities of persons or businesses involved in serious crime and allowing senior police to issue temporary public safety orders to prevent people ‘attending places or events where they are expected to engage in violence or present a serious threat to public safety or security’ (Grant 2016). The reforms which ‘modernise[d] the offence of consorting’ aimed to

better allow the offence to be applied not only against members of criminal groups, but against those on the periphery of such groups who nevertheless contribute to the group’s criminal activity. Criminal groups do not and cannot function in isolation and this offence sends a strong message out to the community (Smith 2012: 47).

The Police Offences Amendment (Prohibited Insignia) Bill 2018 (Tas) was designed to ‘stop OMCG members from using their colours to stand over members of the public and create fear in the community’ (Ferguson 2018). The Serious and Organised Crime Amendment Act 2016 (Qld) repealed a range of laws that had been introduced in response to OMCGs, but its scope was not limited to OMCGs, because ‘serious criminal activity and organised crime extends far beyond those gangs. A proper response to serious and organised crime must be agile enough to counter the threats to the community posed by all forms of organised crime’ (D’Ath 2016: 3400). The new framework was ‘built to withstand all stages of the criminal justice system and, ultimately, is designed to secure actual convictions of serious and organised criminals which will act as a strong deterrent factor against future criminal activity’ (D’Ath 2016).

Notwithstanding these formal explanations, throughout the review period, commentators (eg, Goldsworthy and McGillivray 2017) and indeed policy-makers and governments (eg, Hidding 2017), referred to the ‘tough on crime’ approach taken. This course is not without apparent reason, given that there were a number of high-profile incidents over the review period, including the Sydney airport murder described above, shooting of a 13-year-old girl in NSW, by armed assailants allegedly looking for her brother (see Sydney Morning Herald 2013) and a shooting at a Queensland shopping centre (ABC 2012), and governments are of course responsible for the safety of the community. Yet, some commentators have questioned the practical effectiveness of the ensuing reforms, as well as their underlying intention. On this latter point, Goldsworthy and McGillivray (2017: 111) have posited that ‘the introduction of laws targeting OMCGs may [serve] to temporarily quell public concern and satisfy calls for tougher crime control’. Beyond these matters, however, the question of whether these laws have achieved their desired and articulated effect remains contentious.

Key similarities and differences between the legislative approaches

Table 1 summaries the key features of the reforms and identifies 16 primary areas covered by the legislation. Eight out of nine jurisdictions passed legislation to create new offences, not counting new offences in relation to consorting, ie ‘the offence of association with criminals’ (Loughnan 2019: 8; we note that the term ‘anti-association’ is often used interchangeably with consorting). Eight jurisdictions also legislated to better facilitate intelligence gathering. Queensland and NSW legislated in respect of the most categories (13 and 11 respectively). By contrast, the NT only legislated in relation to four categories.

Every jurisdiction other than the NT created at least one new offence (not including consorting, discussed further below). These new offences related to a range of issues, including:

-

‘drive-by shootings’ (ACT);

-

supporting a criminal organisation (Cth);

-

breaching a serious crime prevention order (NSW);

-

wearing or carrying a prohibited item in a public place (Qld);

-

participating in a criminal group (SA);

-

manufacturing, distributing, supplying, selling or possessing body armour (Tas);

-

intimidating a witness (Vic); and

-

breaching a control order (WA).

The NT was also the only jurisdiction not to pass legislation in respect of intelligence gathering. Some examples include the National Security Legislation Amendment Act (No 1) 2014 (Cth), which provided criminal and civil immunity to Australian Security Intelligence Organisation officers engaged in ‘special intelligence operations’ and the Criminal Investigation (Covert Powers) Act 2012 (WA), which provided for the authorisation, conduct and monitoring of covert law enforcement controlled operations.

It was common (ACT, Cth, NSW, NT, Qld, SA, Vic) to grant additional powers to the police. For example, the Criminal Legislation Amendment (Consorting and Restricted Premises) Act 2018 (NSW) provided police executing a search warrant with more powers to search a person or compel someone to reveal their name and address and/or move on, while the Criminal Organisations Control Amendment (Unlawful Associations) Act 2015 (Vic) allows a senior police officer to issue an unlawful association notice.

Most jurisdictions (Cth, NSW, Qld, SA, Tas, Vic and WA) also passed proceeds of crime and/or (more commonly) unexplained wealth legislation during this period. Australia’s first unexplained wealth laws were introduced in WA in 2000 (see Bartels 2010c). By 2014, all jurisdictions except the ACT had passed such legislation; the ACT followed suit with the passage of the Confiscation of Criminal Assets (Unexplained Wealth) Amendment Act 2020 in July 2020.

All states and territories except Tasmania and the ACT also passed criminal organisations control legislation, establishing (or extending) the statutory framework to have an organisation declared a ‘criminal organisation’. Some jurisdictions passed several pieces of legislation, in order to address resulting constitutional issues. Taking WA as an example, section 6 of the Criminal Organisations Control Act 2012 (WA) provides that the purpose of declaring an organisation as a criminal organisation is to enable control orders to be made to disrupt and restrict the activities of current and former members. A declaration also makes it an offence for anyone to recruit persons to become members of the organisation. Once the Police or Corruption and Crime Commissioner applies for a declaration (s 7), section 13 provides that a judge or retired judge designated under section 26 may make a declaration if satisfied that the respondent is an organisation whose members associate for the purpose of organising, planning, facilitating, supporting or engaging in serious criminal activity and that the organisation represents a risk to public safety and order in WA. Once declared, members of criminal organisations can be subject to a control order, which restricts their activities, for example, by ‘prohibiting them from associating with each other… carrying on certain occupations, possessing firearms and other things, and accessing or using certain forms of technology or communication’ (s 33(2)).

Most jurisdictions (NSW, Qld, SA, Tas and Vic) introduced laws to regulate ‘consorting’, ie ‘the offence of association with criminals’ (Loughnan 2019: 8), while other jurisdictions already had such laws in place. According to Loughnan, concern about serious violent offences associated with OMCGs were ‘the immediate catalyst for the introduction of these laws’ (Loughnan 2019: 16) and, as of 2019, all jurisdictions except the ACT had adopted such offences.

Five jurisdictions (NSW, NT, Qld, SA, Tas) passed legislation seeking to prevent OMCG members from wearing or displaying their insignia. For example, the Statutes Amendment (Serious and Organised Crime) Act 2015 (SA) created offences in relation to people wearing gang-related materials who enter or remain in licensed premises.

Five jurisdictions (ACT, NSW, SA, Tas, Vic) also passed laws to regulate firearms, including the Firearms (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 2015 (Tas), which created a new offence for the possession of stolen firearms, and the Firearms Amendment (Trafficking and Other Measures) Act 2015 (Vic), which requires gang members to show a firearm was not in their possession, when a weapon is found in their vicinity.

Four jurisdictions (NSW, NT, Qld, SA) increased their regulation of specific industries commonly associated with OMCGs. The most commonly regulated industries were tattoo parlours and liquor licensing (see Lauchs et al. 2015).

There were also four jurisdictions (ACT, Qld, Tas, Vic) that passed anti-fortification legislation, in order to prevent the construction of OMCG headquarters and allow police to demolish existing fortifications, building on the legislation already in place in NSW, South Australia, the NT and WA (see generally Bartels 2010b; Lauchs et al. 2015). There are now laws in place in all states and territories (see Goldsworthy and Brotto 2019).

Three jurisdictions (ACT, Qld, SA) made reforms to their sentencing legislation. For example, the Crimes (Serious and Organised Crime) Legislation Amendment Act 2016 (ACT) expanded the categories of offences for which offenders can receive non-association orders (a sentencing option that can be imposed for a substantive offence, which may or may not be associated with OMCG activities) and place restriction orders.

Other reforms were less widely implemented, with two jurisdictions (NSW, Qld) establishing a model for crime prevention orders and/or public safety orders (NSW introduced both in 2016), two other jurisdictions (ACT, Cth) extending the scope of criminal responsibility (including the introduction of ‘joint’ commission and criminal enterprise offences) and two (ACT, Qld) legislating in relation to bail. Five jurisdictions also made other reforms, including in relation to the establishment of the ACT Integrity Commission, criminal procedure and evidence law (NSW), corrections management (Qld) and strengthening the external oversight of Victoria’s witness protection system.

The Commonwealth’s powers are different in scope and its reforms related principally to the Migration Act 1958 (Cth), primarily through the passing of Migration Amendment (Character and General Visa Cancellation) Act 2014 (Cth). This expanded the powers of the Minister to cancel visas on the basis of criminal suspicion or suspicion of criminal association where no criminal offence has been committed. Specifically, the reforms introduced a mandatory character cancellation power, to be exercised by the Minister, if satisfied it is in the national interest and lowered the threshold required for cancelling a visa on the basis of potential future criminal conduct (from ‘significant risk’ to ‘risk’).

How (and how effectively) has the legislation been used to disrupt serious and organised crime activity by OMCGs?

It is possible to assess the effectiveness of legislation in several ways, while noting that there are limitations, based on what information is available. Effectiveness may be assessed by cost savings to the taxpayer; the incidence of crime generally, bearing in mind that OMCG members comprise a very small proportion of the population overall; by examining the proportion of OMCG members charged or convicted under the various pieces of legislation, compared with non-OMCG members; or by identifying whether OMCG membership has declined (or increased) over time. Drawing on our review of the literature, this section provides some examples of how the legislation has been used to disrupt crime by people associated with OMCGs. Due to the lack of evidence on the use of many of the laws, this section focuses on the types of legislation where we were able to identify evidence of and/or commentary on their use. However, it should be noted that there are significant limitations in the data gathered (by governments and other groups) to assess the impact of the numerous and wide-ranging pieces of legislation. Although academic commentators commonly call for evidence on the impact of legislation, this is rarely matched by public or political demand. Further, although some legislative provisions require mandatory review processes, these are not universal and do not always result in the ensuing reports being made publicly available. This contributes to the difficulties in clearly distinguishing between symbolic legislation and legislation that makes a practical difference.

The Commonwealth migration laws have been applied to a number of high-profile OMCG members, including the father of well-known Australian Football League player Dustin Martin (Cunningham 2017). In Graham and Te Puia v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 33, the High Court quashed the Minister’s cancellation of the applicants’ visas, on the basis that the cancellation and parts of the legislation were invalid. Notwithstanding this decision, the Minister proceeded to cancel Graham’s visa a third time (Cunningham 2017). According to Morgan et al. (2018), cancelling and refusing the visas of 184 organised crime offenders (including 139 OMCG members) saved an estimated $116 million, or over $630,000 per offender in taxpayer money.

The Queensland legislation introduced in 2013 was subject to considerable media coverage (eg, Robertson 2015) and academic critique (eg, Cappellano 2014; Goldsworthy and Brotto 2019). It constituted the most expansive range of measures adopted by an Australian jurisdiction over the period, especially the reforms under the Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment (VLAD) Act 2013 (Qld). Most of this legislation and the Criminal Organisation Act 2009 (Qld) were repealed by the Serious and Organised Crime Amendment Act 2016 (Qld), following recommendations of the Taskforce on Organised Crime Legislation (2016). The Taskforce found, inter alia, that, of 202 people charged under the VLAD Act, only 10% were OMCG members, 7 % were associates of OMCGs, 82% had no known linkage to OMCGs. Furthermore, although 42 people were charged with the anti-association offence under the VLAD Act, none were successfully prosecuted for the offence. There was a similar pattern in relation to the new South Australian offence of knowingly participating in a criminal organisation (introduced by the Statutes Amendment (Serious and Organised Crime) Act 2012 (SA)). Of the first 84 people charged, only 10 (12%) were OMCG members (Wilson 2015).

Former Supreme Court judge Alan Wilson SC also found that fortification removal orders had not been used widely:

only three attempts have been made to obtain such an order [in Western Australia]. In South Australia, four attempts have been made. Victoria has filed at least two applications in the short time since its legislation came into force in 2013. There is no evidence of fortification removal orders having been sought or made in other Australian jurisdictions, including Queensland (2015: 136).

He considered that ‘on balance it makes more sense to deal with fortifications in the course of executing a search warrant’ (2015: 222). On the other hand, more recent evidence suggests that visible OMCG clubhouses appear to be generally on the decline. For example, in June 2020, the Queensland Minister for Police and Corrective Services, Mark Ryan (2020) indicated that he had been advised that ‘there are currently no active bikie clubhouses known to Queensland Police’. Similarly, it was reported in October 2019 that there was ‘not a single motorcycle gang left in SA with its own headquarters’ (Penberty 2019: 6), while the number of clubhouses in the ACT fell from five in 2015 to one in 2019 (Goldsworthy and Brotto 2019).

At the time of Wilson’s review, public safety orders were available in the NT, Queensland and SA (they were subsequently introduced in NSW). Wilson found that only SA made significant use of these orders, with 155 orders issued against individual OMCG members in relation to 12–15 events. Reportedly, in all but one case, this dissuaded people from attending the events, ‘thereby potentially avoiding public acts of violence’ (2015: 217) and the South Australian Police accordingly considered that the orders ‘have been very effective in preventing violent activity at public events’ (2015: 151).

Loughnan (2019) has described consorting laws as ‘a useful tool in the toolbox of police powers’. A review of the NSW laws by the NSW Ombudsman (2016b) found that there was evidence to support the effective use of the NSW laws to target high-risk OMCGs. The NSW Police Force Gangs Squad, which leads the NSW policing response to serious and organised gang-related crime, particularly in relation to OMCGs, was responsible for half of the consorting warnings issued and 34 of the 46 charges that had been laid by the time of the review. In South Australia, 12 consorting prohibition notices had been issued to members of declared organisations by late 2015. Media reports suggested that ‘the new laws have resulted in most declared OMCGs abandoning their clubrooms, with their members now gathering in secret’ (Wilson 2015: 158), which may have reduced the OMCGs’ ability to recruit new members.

It is somewhat difficult to determine the extent to which the legislative measures are achieving their goals. Firstly, there is a paucity of evidence on the use (and therefore impact) of some of the legislative measures introduced. Secondly, the measures of effectiveness may not be clearly defined. One measure of ‘success’ is the number of OMCG members. Recent media reports indicate that the number of members in Queensland fell by 18% (from 789 in 2015 to 650 in 2019) over a similar period (Caldwell 2019) and South Australia’s numbers ‘plummeted’ by 30% in three years (Hunt 2019: np). In the ACT, the membership declined from a peak of about 70 in 2018 to ‘in the 30s’ in 2020 (Inman 2020: np).

What barriers to the effective enforcement of the legislation have been identified?

Several legislative regimes have been the subject of legal challenges. A High Court challenge to the constitutional validity of the NSW consorting law introduced in 2012 was unsuccessful (Tajjour, Hawthorne and Forster v NSW [2014] HCA 35). The challenge to the (subsequently repealed) Criminal Organisation Act 2009 (Qld) in Assistant Commissioner Michael James Condon v Pompano Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 7 was also unsuccessful, but prompted the NSW Government to pass the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Amendment Act 2013 (NSW) to address vulnerabilities in its regime. The challenge to the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2009 (NSW), which provided power to seek to declare OMCGs as criminal organisations, was upheld by the High Court in Wainohu v NSW (2011) 243 CLR 181. This led governments to pass the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2012 (NSW) and Serious Crime Control Amendment Act 2011 (NT). The constitutional challenge to the Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Act 2008 (SA) in South Australia v Totani (2010) 242 CLR 1 was also successful. The South Australian Government rectified this issue by passing the Serious and Organised Crime (Control) (Miscellaneous) Amendment Act 2012 (SA) (which also addressed some of the issues raised by Wainohu). The regular interplay between applicants, governments and the judiciary over the survey period prompted McNamara and Quilter to suggest that the strategic use of the High Court’s ‘constitutional court role’ represents an attempt to ‘stop or restrict perceived over-criminalisation’ (2018: 1048–1049). The fact that many of these laws have not survived constitutional challenges begs the question: ‘who is writing these laws?’. Bartels (2009, 2010b), Loughnan (2019), McNamara and Quilter (2016, 2018), O’Sullivan (2019) and others have catalogued and critiqued the circumstances in which such laws have been passed.

The control legislation, which has been subject to the most legal challenges, has been criticised for ‘conflicting with human rights obligations, specifically freedom of association and the reversal of the onus of proof, and as prejudging guilt of members’ (Lauchs 2019: 291; see also Lauchs et al., 2015; Monterosso 2018). There have also been practical issues with control orders. For example, a media report indicated that, seven months after the Victorian legislation was introduced, the police had not yet attempted to use it, as it involved ‘a complex process with a high burden of proof and takes time’ (Lee 2013). Wilson (2015) found that, after seven years of such legislation across six jurisdictions in Australia, only one valid order had been made, in respect of one person and imposing only limited restrictions. The Ombudsman Western Australia (2017: 9) observed that the reasons this type of legislation has not been used include ‘resourcing, agility, timeliness and lack of proportionality of resourcing to the level of benefit achieved’ and recommended that consideration be given to repealing the Criminal Organisations Control Act 2012 (WA). On the basis of analysis of the information put forward by the Queensland Police Service in seeking a control order against the Finks OMCG, Lauchs (2019) concluded that ‘labelling an OMCG as a criminal organization and restricting the movement of its members is not a good use of resources and an unnecessary foray into controversial areas of human rights’. In its review of the relevant legislation, the NSW Ombudsman (2016a: 32) found that the model ‘does not provide police with a viable mechanism to tackle criminal organisations, and is unlikely to ever be able to be used effectively’ and suggested that the model (in NSW and other jurisdictions) would not be improved by further legislative amendment. In fact, the NSW Ombudsman asserted that ‘[c]ontinuing to devote resources to the process of seeking a declaration would not be in the public interest’ (2016a: 32). It appears that the Australian experience in this regard echoes the first decade of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (commonly referred to as RICO) in the United States, which likewise saw limited use for similar reasons (see eg Blakey and Gettings 1980; Calder 2000).

O’Sullivan’s reflection on the Queensland consorting offence introduced in 2016 found that it can apply to associations with no connection with criminal activity, ‘never mind serious or organised crime. By not curtailing the offence to the stated purpose, the law risks disproportionately restricting the right to freedom of association’ (2019: 263). The NSW Ombudsman’s review of the NSW consorting laws found that the NSW police had used the laws to ‘disrupt serious and organised crime and criminal gangs as intended by Parliament (2016b: iii). However, the laws were also used to target minor offending and ‘disadvantaged and vulnerable people’, including Aboriginal, homeless and young people.Footnote 1 This was coupled with ‘an exceptionally high police error rate when issuing consorting warnings in relation to children and young people’ (2016b: iii). Overall, the Ombudsman found, that the laws were used ‘in a manner that, to some extent, illustrated public concerns about its operation’ (2016b: iii) and ‘may be used lawfully to capture people who are participating in everyday, otherwise innocent, social interactions in public spaces, or who are involved in only minor or nuisance offending’ (2016b: 116). Accordingly, the Ombudsman recommended statutory and policy amendments to increase the fairness of the law’s operation and to mitigate the unintended impacts of its operation in circumstances where there is no minor crime prevention benefit, as well as a new statutory and policy framework to ensure its use ‘is focused on serious crime’ (2016b: iii). The Ombudsman suggested that this would be consistent with Parliament’s overarching intention of combatting serious and organised crime and criminal groups, and that adopting the recommendations was ‘essential to maintain public confidence in the NSW Police Force’ (2016b: iii). These findings echo critiques of the application of RICO in the United States, introduced in 1970 in an attempt to curtail Italian-American mafia syndicates’ infiltration into legitimate businesses, but which has since been applied to a wide range of contexts which fall outside the definition of organized crime (Lynch 1987; Morselli and Kazemian 2004).Footnote 2

These observations are salutary in the broader context of legislation designed to regulate OMCGs and echo some of the concerns with the now repealed Queensland legislation. Excessive legislative reform and use of any ensuing powers will undermine public confidence in the justice system, which may in turn undermine the very goals that governments are trying to promote through their attempts to regulate OMCGs.

The foregoing analysis suggests that some of the measures adopted by governments over the last decade have raised human rights concerns, have not been used widely, have been used inappropriately and/or have constituted an inefficient use of resources (including the costs of legal challenges) in pursuit of their goals. It has also been suggested that laws of this nature may ‘drive OMCGs underground’, which may in turn ‘lead to consolidation and growth of OMCG’s along with increased potential for violent turf type conflict’ (Monterosso 2018: 694). Furthermore, the Queensland Organised Crime Commission of Inquiry found that the evidence before it indicated that ‘the focus upon – and resources solely dedicated to – the threat of outlaw motorcycle gangs by the QPS [Queensland Police Service] has meant that other types of organised crime have not been able to be appropriately investigated’ (2015: 26).

Some commentators have suggested that a focus on criminal organisations, rather than on individual liability, presents challenges for legislators. For example, Monterosso observed that:

In targeting structures, activities, objectives and impacts of criminal organisations rather than a traditional criminal justice approach focussed on individual liability, legislators are faced by a number of constraints including development of workable definitions of organisations, membership including whether participant criminality can be attached to the same, suitability of sanction and distribution of legal responsibility between organisation and members. The criminalisation of association also remains problematic as the notion that an actor will commit harmful acts in the future rather than for identified offending is tenuous as a person may be liable for anti-association offences without committing or intending to commit an offence (2018: 688).

Goldsworthy and Brotto (2019) have also suggested that there is little evidence that anti-association or consorting laws reduce overall offending. Instead, they contended that:

The resources used to police such laws would be better invested in targeting actual criminal activities, rather than in generalised claims of disruption through stopping associations between individuals, in which there is no requirement for a criminal purpose to be attached (2019: 8).

It should also be recognised that all jurisdictions have a broad range of powers available to them to deal with crime generally. As Wilson noted in his review of the (subsequently repealed) Criminal Organisation Act 2009, ‘[w]e already have a comprehensive Criminal Code, and ancillary legislation dealing with particular problems like drugs, sufficient to address any criminal act an OMCG member might commit’ (2015: 13). It is also indicative that, in what was the ‘largest operation on a single bikie gang in Victoria’s history’, the Victorian police used ‘warrants to carry out the searches, rather than making court applications under [the new] anti-fortification laws’ (Lee 2013), suggesting that general police powers may be adequate.

Conclusion

In recent years, Australian governments have passed a range of legislative reforms to disrupt and deter crimes committed by OMCG members. The majority of these legislative reforms have been implemented despite legal challenges and a lack of empirical evidence as to their effectiveness. The passage of these reforms is likely due to the real and perceived threat of OMCGs, beginning with an apparent upsurge in ‘bikie gang violence’ (ABC News 2009) from early 2009, coupled with Australian governments’ policies of being ‘tough on crime’ (Hidding 2017).

This paper has provided an overview of the breadth and depth of legislative activity in the period 2009–2019, highlighting key similarities and differences. The paper then presented examples of this legislation being used to disrupt OMCGs’ serious and organised crime activities and barriers to the effective enforcement of the legislative responses. This demonstrated that the examples of effective operation of the legislation are limited and there are a number of practical and human rights barriers to such frameworks.

In some instances, it may be more effective to employ traditional powers and offences. In addition, police could engage OMCG leadership in efforts to identify and strategically remove the criminal elements in their membership (Monterosso 2018). Jahnsen has also highlighted the Scandinavian approach of coupling ‘traditional efforts to deter OMCG crimes and the development of more innovative strategies that seek to prevent recruitment to gangs and encourage dissociation and desistance’ (2018: 12). Finally, regardless of the approaches adopted, governments should ensure their models are practicable and an effective and efficient use of the limited resources available.

Wilson (2015: 229) observed that ‘any legislative attempt to meet the risk posed by organised crime should be evidence-based; it should reflect and respond to the actual nature and extent of that risk, as it is revealed in the available evidence’. As Wilson also noted, however, ‘a balanced legislative response to organised crime should be proportional to the risk posed by its various facets — ie, to the level of danger and potential harm presented by different kinds of organised criminal activity’ (2015; see also Lauchs et al., 2015).

Goldsworthy and Brotto have suggested that ‘bikers are the “poster boys” of organised crime’ (2019: 54), but described their involvement as ‘insignificant’ (2019: 49) and ‘overstated’ (2019: 55). Specifically, they found that OMCGs accounted for less than 1% of reported crime in the ACT (although the recent alleged murder of a ‘bikie boss’ should be noted (see eg Bradshaw 2020)). Wilson (2015) found a similar result in Queensland. Lauchs and Staines’ (2019) analysis in Queensland found that OMCG members did participate in serious crime (especially violent crime) at a higher rate than the general public, but this was concentrated in two groups, with few examples of organised crime and ‘little to no evidence of OMCGs acting as criminal organisations’ (2019: 69). Goldsworthy and Brotto considered it ‘tenuous that the breaking up of incidents of association with no obvious criminality or criminal purpose will directly affect the disruption of serious and organised crime. No quantitative evidence has been offered to substantiate such claims’ (2019: 67; see also Montessero 2018).

Notwithstanding the apparent small proportion of OMCG-related crime, Morgan et al. (2018) found that the average cost of offending per OMCG member, based on crime and prison costs, is $1.3 million and that they commit more crimes and more serious crimes than other organised crime offenders. There is also evidence that at least some OMCG members play a significant role in organised crime in Australia, especially in relation to drug and firearms trafficking, tax evasion, money laundering and serious violent crime (Morgan et al., 2020; see also Monterosso 2018). Other Australian Institute of Criminology analysis found that, across Australia, 85% of 5665 OMCG members born in 1984 had been apprehended for at least one offence by the age of 33 (Morgan et al., 2020), compared with 33% of all men born in NSW in 1984 (Weatherburn and Ramsey 2018). Morgan, Dowling and Voce accordingly noted the ‘high prevalence of offending among OMCG members, including involvement in violence and intimidation and organised crime offending’, although this was ‘concentrated among a small proportion of offenders’ (2020: 14). However, it should be acknowledged that this was based on charge (rather than conviction) data. Charge data arguably overstates the magnitude of the issue, especially noting Goldsworthy and Brotto’s (2019) finding that 27% of charges against OMCG members in the ACT were not proven in court, compared with 4% of all ACT charges.

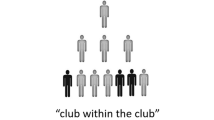

Another aspect that is yet to be determined in the Australian context is OMCGs’ role in their members’ criminal activities. This also has implications for how these organisations and their members should be regulated. Von Lampe and Blokland (2020) have recently posited three scenarios (and suggested that all may occur simultaneously in the one club in relation to different crimes):

-

the ‘bad apple’ scenario, where members individually engage in crime, which club membership may enable and facilitate;

-

the ‘club within a club’ scenario, where members engage in crimes separate from the club, but it appears that the club is taking part, because of the number of members involved, including high-ranking members; and

-

the club as a criminal organisation, when the formal organisational chain of command participates in organising crime, lower-level members ‘regard senior members’ leadership in the crime as legitimate and the crime is generally understood as “club business”’ (2020: 1).

Von Lampe and Blokland noted that the latter scenario ‘appears to be widely shared among law enforcement officials and journalists. The academic literature is much more cautious’ (2020: 40). Future research should therefore consider the applicability of this framework to Australian OMCG clubs and members. It may also help to develop legislative responses that effectively target OMCG crime, without targeting the clubs’ non-criminal members and activities or members of the public more generally.

Notes

Earlier analysis by the NSW Ombudsman (2013) found that Aboriginal people accounted for 38% of all people issued an official warning, even though they only accounted for 2.5% of the population. The rates of Aboriginal people targeted by the consorting laws appears to be increasing. An internal memo circulated to a parliamentary committee investigating the high rates of Aboriginal incarceration in NSW, as part of a recent review by the Law Enforcement and Conduct Commission found that 40% of people subjected to the consorting laws in NSW over an 18-month period to June 2019 were Aboriginal (McGowan 2020).

RICO has been used to prosecute not just organized crime enterprises, but corruption in labour unions and other types of organizations.

References

AAP (2010) Zervas died after brawl, court hears. Sydney Morning Herald. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/zervas-died-after-brawl-court-hears-20100712-107n0.html. Accessed 2 March 2021

ABC News (2009) Timeline of bikie gang violence. Available at: https://wwwabcnetau/news/2009-03-30/timeline-of-bikie-gang-violence/1636456. Accessed 2 March 2021

ABC News (2012) Police say bikie violence worst Queensland has seen. Available at: https://wwwabcnetau/news/2012-04-29/police-say-bikie-violence-is-worst-queensland-has-ever-seen/3978444. Accessed 2 March 2021

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020) Federal defendants, Australia. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/federal-defendants-australia/2018-19. Accessed 2 March 2021

Bartels L (2009) The status of laws on outlaw motorcycle gangs in Australia. Research in practice no. 2, 1st edn. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

Bartels L (2010a) A review of confiscation schemes in Australia. Technical and background paper no. 36. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

Bartels L (2010b) The status of laws on outlaw motorcycle gangs in Australia. Research in practice no. 2, 2nd edn. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

Bartels L (2010c) Unexplained wealth laws in Australia. Trends & Issues in crime and criminal justice no. 395. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

Blakey G, Gettings B (1980) Racketeer influenced and corrupt organizations (RICO): basic concepts – criminal and civil remedies. Temp L Q 53:1009–1048

Bradshaw A (2020) Man charged with murder over death of bikie boss at crowded Canberra bar. Canberra Times. Available at: https://www.9news.com.au/national/man-charged-over-murder-of-act-comanchero-bikie-boss-pitasoni-ulavalu-at-kokomos-bar/4a262146-d2cc-40b7-b0b6-2b80cf2c9c9e. Accessed 2 March 2021

Calder J (2000) RICO’s ‘troubled . . . transition’: Organized crime, strategic institutional factors, and implementation delay, 1971–1981. Crim Justice Rev 25:31–75

Caldwell F (2019) Push to force out bikies leads to 139 fewer patched members in four years. Brisbane Times. Available at: https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/politics/queensland/push-to-force-out-bikies-leads-to-139-fewer-patched-members-in-four-years-20190618-p51yqt.html. Accessed 2 March 2021

Cappellano A (2014) Queensland’s new legal reality: four ways in which we are no longer equal under the law. Griffith J of Law and Hum Dignity 2:109–125

Commonwealth of Australia (2014) Migration Amendment (Character and General Visa Cancellation) Bill, 2014 Explanatory Memorandum, House of Representatives, 10 December 2014. Available at https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r5345

Corbell S (2010) Crimes (Assumed Identities) Bill 2009 Second Reading Speech. ACT Legislative Assembly, 20 August 2010. Available at https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=s761. Accessed 2 March 2021

Corbell S (2016) Crimes (Serious and Organised Crime) Legislation Amendment Bill 2016 Second Reading Speech. ACT Legislative Assembly, 9 June 2016

Council of Attorneys-General (2020) About us. Available at: https://www.ag.gov.au/about-us/committees-and-councils/council-attorneys-general-cag. Accessed 2 March 2021

Cunningham M (2017) Rebels boss Aaron ‘AJ’ Graham latest bikie to be kicked out of the country. Sydney Morning Herald. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/rebels-boss-aaron-aj-graham-latest-bikie-to-be-kicked-out-the-country-20171017-gz2w5f.html. Accessed 2 March 2021

D’Ath Y (2016) Serious and Organised Crime Legislation Amendment Bill 2016 Second Reading Speech. Queensland Legislative Assembly, 13 September 2016

Ferguson (2018) Police Offences Amendment (Prohibited Insignia) Bill 2018 Second Reading Speech. Tasmanian Legislative Assembly, 21 August 2018

Goldsworthy T, McGillivray L (2017) An examination of outlaw motorcycle gangs and their involvement in the illicit drug market and the effectiveness of anti-association legislative responses. Int J Drug Policy 41:110–117

Goldsworthy T, Brotto G (2019) Independent review of the effectiveness of ACT policing crime scene powers and powers to target, disrupt, investigate and prosecute criminal gang members. Bond University, Robina

Grant T (2016) Crimes (Serious Crime Prevention Orders) Act 2016 (NSW) and Crimes Legislation Amendment (Organised Crime and Public Safety) Act 2016 Second Reading Speech. NSW Legislative Assembly, 22 March 2016

Hidding R (2017) Tough on crime approach working. Media release Available at: http://wwwpremiertasgovau/releases/tough_on_crime_approach_working. Accessed 2 March 2021

Hunt N (2019) How SA police beat the bikies. Adelaide Advertiser. 27 April 2019, 11. Available at: https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/truecrimeaustralia/gangs-demolished-bikies-quit-as-new-laws-police-tactics-prevail/news-story/9334e0528a2d98dcbcb9508a74fd18f1

Inman M (2020) Canberra bikie numbers halved by deportations, sustained police pressure. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-13/canberra-bikie-numbers-down-by-half-since-2018-police-say/12143314. Accessed 2 March 2021

Jahnsen S (2018) Scandinavian approaches to outlaw motorcycle gangs. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice no. 543. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

Lauchs M, Staines Z (2019) An analysis of outlaw motorcycle gang crime: are bikers organised criminals? Global Crime 20(2):69–89

Lauchs M (2019) Are outlaw motorcycle gangs organized crime groups? An analysis of the finks MC. Deviant Behav 40(3):287–300

Lauchs M, Bain A, Bell P (2015) Outlaw motorcycle gangs: a theoretical perspective. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Lee J (2013) Police neglect anti-bikie law due to high complexity. The Age Available at: https://wwwtheagecomau/national/victoria/police-neglect-anti-bikie-law-due-to-high-complexity-20131011-2ve1mhtml. Accessed 2 March 2021

Loughnan A (2019) Consorting, then and now: changing relations of responsibility. Uni West Aust Law Rev 45(2):8–36

Lynch G (1987) RICO: the crime of being a criminal. Parts I & II. Columbia Law Rev 87(4):661–764

McGowan M (2020) Motorcycle gang laws overwhelmingly target indigenous Australians, police watchdog reveals The Guardian Available at https://wwwtheguardiancom/australia-news/2020/dec/08/motorcycle-gang-laws-overwhelmingly-target-indigenous-australians-police-watchdog-reveals. Accessed 2 March 2021

McNamara L, Quilter J (2016) The ‘bikie effect’ and other forms of demonisation: the origins and effects of hyper-criminalisation. Law Context 34(2):5–35

McNamara L, Quilter J (2018) High court constitutional challenges to criminal law and procedure legislation. Uni NSW Law J 41(4):1047–1082

Monterosso S (2018) From bikers to savvy criminals. Outlaw motorcycle gangs in Australia: implications for legislators and law enforcement. Crim Law Soc Chan 69(5):681–701

Morselli C, Kazemian L (2004) Scrutinizing RICO. Crit Criminol 12:351–369

Morgan A, Darling C & Voce I (2020) Australian outlaw motorcycle gang involvement in violent and organised crime. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice no. 586. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology

Morgan A, Brown R, Fuller G (2018) What are the taxpayer savings from cancelling the visas of organised crime offenders? In: Statistical Report no. 8. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

NSW Ombudsman (2013) Consorting issues paper: Review of the use of the consorting provisions by the NSW police force. Sydney

NSW Ombudsman (2016a) Review of police use of powers under the crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2012. Sydney

NSW Ombudsman (2016b) The consorting law: report on the operation of part 3A, division 7 of the crimes act 1900. Sydney

Odgers S (2019) Principles of Federal Criminal law, 4th edn. Thomson Reuters, Sydney

O’Sullivan C (2019) Casting the net too wide: the disproportionate infringement of the right to freedom of association by Queensland’s consorting laws. Aust J Human Rights 25(2):263–280

Ombudsman Western Australia (2017) Report by the parliamentary commissioner for administrative investigations under section 158 of the criminal Organisations control act 2012 for the whole monitoring period. Perth

Penberty D (2019) Full throttle on bikies’ assets sale. The Australian Available at: https://wwwtheaustraliancomau/nation/politics/full-throttle-on-hells-angels-bikies-assets-sale/news-story/dbf4fff6b55b342e4841808b1dc552ca. Accessed 2 March 2021

Queensland Organised Crime Commission of Inquiry (2015) Report. Queensland Government, Brisbane

Robertson J (2015) Vlad anti-bikie laws criticised for absurd name and attack on judges. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/aug/19/vlad-anti-bikie-laws-criticised-for-absurd-name-and-attack-on-judges. Accessed 2 March 2021

Ryan M (2020) Gold Coast police cracking down on organised crime. Media release. http://statements.qld.gov.au/Statement/2020/6/18/gold-coast-police-cracking-down-on-organised-crime. Accessed 2 March 2021

Smith G (2012) Crimes Amendment (Consorting and Organised Crime) Bill 2012 (NSW) Second Reading Speech. NSW Legislative Assembly, 14 February 2012

Sydney Morning Herald (2013) Barry O’Farrell cracks down on Brothers 4 life over drive-by shootings. Available at: https://wwwsmhcomau/national/nsw/barry-ofarrell-cracks-down-on-brothers-4-life-over-drive-by-shootings-20131108-2x6wthtml. Accessed 2 March 2021

Taskforce on Organised Crime Legislation (2016) Report. Queensland Government, Brisbane

Von Klampe K, Blokland A (2020) Outlaw motorcycle clubs and organized crime. In: Tonry M, Reuter P (eds) Organizing crime: mafias, markets and networks. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Weatherburn D, Ramsey S (2018) Offending over the life course: contact with the NSW criminal justice system between age 10 and age 33. Bureau brief no. 132. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Wilson A (2015) Review of the criminal organisation act 2009. Queensland Government, Brisbane

Acknowledgments

This research received financial support from the Australian Institute of Criminology. The authors are grateful to Dr. Adam Masters, Anthony Morgan, Isabella Voce and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bartels, L., Henshaw, M. & Taylor, H. Cross-jurisdictional review of Australian legislation governing outlaw motorcycle gangs. Trends Organ Crim 24, 343–360 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09407-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09407-0