Abstract

Objectives

To understand the characteristics of autistic regression and to compare the clinical and developmental profile of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in whom parents report developmental regression with age matched ASD children in whom no regression is reported.

Methods

Participants were 35 (Mean age = 3.57 y, SD = 1.09) children with ASD in whom parents reported developmental regression before age 3 y and a group of age and IQ matched 35 ASD children in whom parents did not report regression. All children were recruited from the outpatient Child Psychology Clinic of the Department of Pediatrics of a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. Multi-disciplinary evaluations including neurological, diagnostic, cognitive, and behavioral assessments were done. Parents were asked in detail about the age at onset of regression, type of regression, milestones lost, and event, if any, related to the regression. In addition, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) was administered to assess symptom severity.

Results

The mean age at regression was 22.43 mo (SD = 6.57) and large majority (66.7%) of the parents reported regression between 12 and 24 mo. Most (75%) of the parents of the regression-autistic group reported regression in the language domain, particularly in the expressive language sector, usually between 18 and 24 mo of age. Regression of language was not an isolated phenomenon and regression in other domains was also reported including social skills (75%), cognition (31.25%). In majority of the cases (75%) the regression reported was slow and subtle. There were no significant differences in the motor, social, self help, and communication functioning between the two groups as measured by the DP II.There were also no significant differences between the two groups on the total CARS score and total number of DSM IV symptoms endorsed. However, the regressed children had significantly (t = 2.36, P = .021) more social deficits as per the DSM IV as compared to the non-regressed children with autism.

Conclusions

Autism with regression is not characterized by a distinctive developmental or symptom profile. Developmental regression may, however, be an early and reliable marker in a significant number of children with autism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) are neuro-developmental disorders characterized by qualitative impairments in social interaction and communication along with restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped patterns of behavior and interests [1]. For majority of the children, behavioral disturbances manifest gradually in the first two years of life and this atypical development has been corroborated by retrospective home video analyses, which reveal that children with an ASD show clear developmental differences by 9–12 mo of age [2]. Recently several researchers have reported that a substantial minority of children with ASD may experience an autistic regression in one or more developmental domains between 18 and 24 mo of age [3–5]. Regression among ASD children is generally defined as a loss of previously acquired social, communication, and/or motor skills prior to 36 mo of age [3, 6, 7]. Autistic regression is distinguished from childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD), which typically emerges between 3 and 4 y of age and involves regression in multiple areas of functioning, including motor and adaptive functioning. Children who regress around the second year of life are almost always diagnosed with an ASD after loss of skills [3, 8]. Underlying mechanisms that lead to these losses are unknown and, hence are a basis of much controversy and debate [8, 9] The prevalence of regression in children with ASD ranges from 15% to 49% [5, 10, 11].

Regression in children with autism has made many researchers interested in the issue whether children with ASD who experience a regression manifest a new phenotype of the disorder [4]. To address this research question studies have been conducted comparing children with ASD with and without regression. There is little empirical data on autism in India in general, and none about autistic regression. The aims of the present study are to understand the characteristics of autistic regression; and to compare the clinical and developmental profile of children with ASD in whom parents report developmental regression with age and IQ matched ASD children in whom no regression is reported.

Material and Methods

The participants included 35 children with ASD (Mean age 3.47 y, S.D. = 0.93) in whom parents reported developmental regression before age 3; and age and IQ matched group of 35 children with ASD in whom parents did not report regression. All children were recruited from the outpatient Child Psychology Clinic of the Department of Pediatrics of a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. The inclusion criteria for all children were a diagnosis of ASD, absence of metabolic or genetic disorders, and absence of sensory or motor impairment. Consistent with methods employed by previous studies of regression, children with a reported loss of skill after 3 y of age; children with a diagnosis of Child Disintegrative Disorder (CDD); and Rett’s disorder were not included in the sample [3, 6]. Complete physical and neurological examination; and cognitive and adaptive behavior assessment were done for all children. The detailed description of the sample is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

The following tools were administered:

-

Developmental Profile II A detailed developmental assessment was done using the Developmental Profile II (DP II) [12]. The DP II is 186 items inventory which assesses the child’s developmental status from birth to 9½ y. The DP II assesses child’s developmental age in five domains namely physical, social, self help, academic, and communication. The academic scale assesses a range of skills necessary for success in school including language, cognition, and scholastic accomplishments. The IQ calculated from the academic scale has been found to have moderate to high correlation with conventional measures of intelligence. In the present study the IQ of the subjects was calculated from the academic sub scale of the DP II. The DP II has been used in several previous studies in India to measure developmental functioning in children, including autism.

-

Vineland Social Maturity Scale The adaptive behavior of the child was measured by the Indian adaptation of the Vineland Social Maturity Scale [13]. The 89 items scale is a standardized developmental schedule which measures level of social competence and assesses several areas of functioning including self help (general), self help (eating) self help (dressing), self direction, occupation, locomotion and socialization. The scale yields two scores, social age and social quotient (SQ). The SQ is a measure of a child’s social competence and the ability to perform daily living tasks.

-

Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) The CARS [14] is a 15 item rating scale which elicits information on the child’s behavior with respect to socialization, communication, emotional responses, and sensory sensitivities. The child is rated on each item based on the clinician’s observation of the child’s behavior as well as on the parent’s report. Each item is scored on a continuum from normal scored as 1 to severely abnormal scored as 4. Scores for all the 15 items are summed to yield a total score that ranges from 15 to 60. The cut-off score for diagnosis of autism is 30. Scores from 30 to 37 are categorized as mildly-moderately autistic and scores above 37 are categorized as severely autistic. The CARS was administered as a measure of symptom severity.

The clinical assessment consisted of a semi-structured interview, clinical history, extended observations of the child on more than two occasions, parental descriptions of the child’s behavior, use of parental diaries of child’s behavior for a minimum of 2 wk, and CARS. In addition, parents were asked in detail about the age at onset of regression, type of regression, milestones lost, and event, if any, related to the regression.

Results

The mean age at regression was 22.43 mo (SD = 6.57) and large majority (66.7%) of the parents reported regression between 12 and 24 mo. Most (75%) of the parents of the regression-autistic group reported regression in the language domain, particularly in the expressive language sector, usually between 18 and 24 mo of age. Analysis of speech loss revealed that prior to regression most of the children (86.7%) used words at the single word level and had vocabularies of less than five words. Children with word losses rarely had a mastery of phrase speech prior to the regression and only a small proportion (28.1%) of children with word loss were able to speak in two to three-word sentences. Vocabularies comprised of words commonly acquired early in life such as mama, papa, or greetings (jai, namaste) or saying bye-bye. Furthermore, prior to regression most children had a vocabulary of few words only and the highest reported vocabulary of 10 words. Forty four percent of the children caught up with development after a plateau in development.

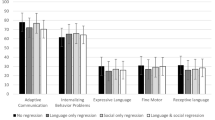

Regression of language was not an isolated phenomenon and regression in other domains was also reported including social skills (75%), cognition (31.25%) (Fig. 1). Regression in social skills was evident in poor eye contact, loss of social smiling, loss of interest in others, increased level of withdrawal behavior, and problems in play. No parent reported loss in higher order social skills such as elaborate imaginative play. Fifteen percent parents reported increase in behavioral difficulties like temper tantrums, increased hyperactivity, and stereotypic behaviors along with regression. On an average parents reported regression in 2 developmental domains (SD = 0.91) with 37.1% of the children regressing in one domain, 28.6% in 2 domains, and 31.3% in 3 or more domains (Fig. 2). Loss in other self care abilities such as dressing, feeding, and dressing were not reported by any parent. No parent reported regression in the motor domain. The occurrence of regression was in most cases associated with delayed development prior to the regression.

In majority of the cases (75%) the regression reported was slow and insidious, although about one fourth of the cases demonstrated more abrupt onset that became evident over course of days or a few wks. A little more than one-third of the parents (37.1%) of children with autistic regression identified a precipitating event related to regression such as medical illness, (30.7%), preoccupation of the mother with her job and/or studies (23%), and change of a caretaker (7.6%). Only one parent reported that the regression had occurred after the MMR vaccination. Most parents did not seek immediate professional help at the time of the regression until at least months or even a year later, and the average time lag in seeking professional help was 13.75 mo (SD = 9.46). Parents believed that the child would gradually recover.

Parents’ age and socio-economic status were similar in the regressed and non-regressed groups. There were no significant differences in the motor, social, self help, and communication functioning between the two groups as measured by the DP II. There were also no significant differences between the two groups on the total CARS score (t = 0.33, n.s), and total number of DSM IV symptoms endorsed (t = 0.81, n.s), however, the regressed children had significantly (t = 2.36, P = .021) more social deficits (M = 3.53, SD = .56) as compared to the non-regressed children with autism (M = 3.05, SD = 1.05).

Discussion

In the present study, 35 ASD children with regression were compared to a group of ASD children without regression to understand the characteristics of autistic regression; and to compare their clinical and developmental profile. The results indicated that majority of the children experienced a developmental regression between 12 and 24 mo of age around a mean age of 22 mo. The results of the present study are very similar to studies done in the Western countries on smaller samples which have reported regression usually between 15 mo to 30 mo of age, with most cases regressing between 18 and 24 mo [8–10, 15]. There are several methodological difficulties inbuilt in accurately assessing the age of onset. Since information about regression is usually obtained retrospectively from parents several months after onset, parental reports may be confounded by other factors such as the concurrent emergence of behavioral problems or family stresses. Inconsistency in parental recognition of symptoms may make it difficult to separate age of onset from age of recognition [5].

In addition, majority of the parents of the regression-autistic group reported regression in the language domain, particularly in the expressive language sector, usually between 18 and 24 mo of age. Analysis of speech loss revealed that prior to regression most of the children used words at the single word level and had vocabularies of less than five words. Apparently, the speech loss associated with autistic regression occurs in children who have a very limited verbal range. Kurita [6], in one of the earliest large scale studies of autistic regression found that 37% of the 261 children with autism studied showed a loss of speech prior to 30 mo of age.

Although the cause of the regression in autism is not known, most parents usually search for a cause for a change in their children development including abnormal medical and social environmental factors. In the present study, a little more than one-third of the parents with children with autistic regression identified an identifiable event related to regression such as medical illness, immunization, preoccupation of the mother with her job and/or studies, and change of the caretaker. Previous studies too have attempted to identify triggers that precede regression. For example, Kurita et al. [16] reported that 25% of the parents of children with autism reported some precipitating event, including physical illness (7%), and various psychosocial events such as birth of a sibling, parental absence (18%). Goldberg et al. [17] reported that nearly half of the parents of 44 children recalled a precipitating event. Some researchers have suggested that regression could be triggered by the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine [18]. However, in the present study only 1 out of the 35 parents reported the MMR vaccine as a triggering event for the regression. Like previous studies, the present study provided no evidence for an association between the MMR vaccination and autistic regression [19, 20].

Results indicated that regression of language was not an isolated occurrence and regression in other domains was also reported including social skills, cognition, and behavior. Loss in other self care abilities such as dressing, feeding, and dressing were not reported by any parent. Goldberg et al. [17] and Hansen et al. [21] reported one third to half of the children studied with regression had both social and language losses, while a fifth to over one-third presented with social losses alone, respectively.

The occurrence of regression was in most cases associated with delayed development prior to the regression. No parent reported regression in the gross motor functioning thereby indicating that the developmental regression in children with autism was not a global developmental regression. It seems then that most of the ASD children with regression in the present study who lost skills showed atypical development prior to the loss and that the majority of these children lost words rather than phrase speech or conversational speech. These findings are in line with previous studies which have demonstrated that ASD children with regression often display developmental deviations prior to the loss [6, 7, 17, 22, 23]. It is, however, not clear whether there are long term differences in the outcomes between children whose development is delayed before the regression and those who regress after gaining more advanced skills such as phrase speech. Research also suggests that early, speech loss is fairly specific to ASD and is relatively uncommon in children with intellectual disabilities or other developmental problems [24].

In the present study few differences were found between ASD children who regressed and those who did not. Moreover, no differences were found in symptom severity as measured by the CARS in children who regressed and those who did not regress. The present findings are consistent with several previous studies that did not find differences related to regression status on most measures of developmental, demographic, or medical measures [14, 21, 25]. However, Meilleur and Fombonne [19] did report that ASD children who regressed as compared with those who did had a more severe autistic symptomatology profile, especially in the repetitive behaviour domain. In this context, it may be noted that in the present study, ASD children with regression as compared to ASD children with no history of regression had more social deficits. Different results in the literature have led some authors to conclude that, similar to children with ASDs, children with autistic regression represent a heterogeneous group who display different profiles and developmental trajectories [20].

In sum, the results of the study indicate that autism with regression is not characterized by a distinctive developmental or symptom profile, when an age and IQ matched sample of ASD children is used for comparison. Developmental regression may, however, be an early and reliable marker in a significant minority of children with autism.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Osterling J, Dawson G. Early recognition of children with autism: a study of first birthday home videotapes. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:247–57.

Lord C, Shulman C, DiLavore P. Regression and word loss in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:936–55.

Rogers S. Developmental regression in autism spectrum disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:139–43.

Stefenatos GS. Regression in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18:305–19.

Kurita H. Infantile autism with speech loss before the age of thirty months. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:191–6.

Luyster R, Richler J, Risi S, et al. Early regression in social communication in autism spectrum disorders: a CPEA Study. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;27:311–36.

Shinnar S, Rapin I, Arnold S, et al. Language regression in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;24:185–91.

Tuchman R, Rapin I. Regression in pervasive developmental disorders: seizures and epileptiform electroencephalogram correlates. Pediatrics. 1997;99:560–6.

Davidovitch M, Glick L, Holtzman G, Tirosh E, Safir MP. Developmental regression in autism: maternal perception. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:113–9.

Parr JR, Couteur AL, Baird G, et al. Early developmental regression in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from an International Multiplex Sample. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:332–40.

Alpern B, Boll T, Shearer M. Developmental Profile II (DP II). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1986.

Malin AJ. The Indian adaptation of the Vineland Social Maturity Scale. Lucknow: Indian Psychological Corporation; 1971.

Schopler E, Reichler R, Renner BR. The childhood autism rating scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1988.

Wiggins LD, Rice CE, Baio J. Developmental regression in children with autism spectrum disorders identified by a population-based surveillance system. Autism. 2009;13:357–74.

Kurita H, Kita M, Miyake Y. A comparative study of development and symptoms among disintegrative psychosis and infantile autism with and without speech loss. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;22:175–88.

Goldberg WA, Osann K, Filipek PA, et al. Language and other regression: assessment and timing. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:607–16.

Wakefield AJ. Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:951–4.

Meilleur AA, Fombonne E. Regression of language and non-language skills in pervasive developmental disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53:115–23.

Richler J, Luyster R, Risi S, et al. Is there a “regressive phenotype” of autism spectrum disorder associated with the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine? A CPEA study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:299–316.

Hansen R, Ozonoff S, Krakowiak P, et al. Regression in autism: prevalence and associated factors in the CHARGE study. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:25–31.

Landa R, Holman KC, Garrett-Mayer E. Social and communication development in toddlers with early and later diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:853–64.

Werner E, Dawson G, Munson J, Osterling J. Variation in early developmental course in autism and its relation with behavioral outcome at 3–4 y of age. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35:337–50.

Wilson S, Djukic A, Shinnar S, Dharmani C, Rapin I. Clinical characteristics of language regression in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:508–14.

Jones LA, Campbell JM. Clinical characteristics associated with language regression for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:54–62.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Role of Funding Source

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malhi, P., Singhi, P. Regression in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Indian J Pediatr 79, 1333–1337 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-012-0683-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-012-0683-2