Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the common malignancies worldwide. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in miRNA-binding site on gene transcripts are reported to play important role in increased risk of CRC in different population. We performed a case–control study using 88 CRC patients and 88 non-cancer counterparts to evaluate the association between NOD2 rs3135500 polymorphism located at 3′ untranslated region of the gene and risk of sporadic CRC. Genotyping of rs3135500 polymorphism was performed by polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) assay. We found a significant association of AA genotype with risk of CRC (adjusted OR 3.100, CI 1.621–5.930, p < 0.001). Also, significant difference in physical activity (p = 0.001) between case and control groups was found. We also found that individuals in control group were more aspirin or NSAID user compared to sporadic CRC cases (p = 0.002). In the case group, individuals with GG genotype consumed more aspirin or NSAID compared with AA+AG genotypes (33.3 vs. 9.6 %, adjusted OR 4.71, CI 1.25–17.76, p = 0.02). However, in the control group, individuals with AA+AG genotypes used more aspirin or NSAID compared with GG genotypes (47.2 vs. 11.4 %, adjusted OR 14 %, CI 0.05–0.47, p < 0.001).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third common malignancy worldwide [1, 2]. The incidence of CRC in Iran is on steady rise and currently this malignancy ranks as fourth most common type of cancer among both genders [3].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have important role in posttranscriptional gene regulation. miRNAs are small endogenous RNA molecules that regulate gene expression by binding to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs and lead to target mRNA cleavage or translational repression [4–6]. Recent studies show linkage between altered miRNA expression patterns and cancer development [7, 8]. On the grounds that the efficiency of miRNA–mRNA interaction can be influenced by thermodynamic characteristics of binding and hybridization site, polymorphisms in 3′UTR of target mRNA might modify miRNA–mRNA binding and also alter target gene regulation thereby influencing individuals’ risk of cancer [6, 9–11].

Recent studies show that among the CRC-related genes, inflammatory response genes are playing prominent role [12, 13]. One of the key regulators of chronic inflammatory condition is the nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) gene. NOD2 protein is an intracellular protein expressed in monocytes and macrophages and through its leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain situated at its C-terminal region act as a sensor for bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and peptidoglycans (PGN), result in activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor (NF)-κB, STAT1, which play important roles in inflammation-linked tumor development [13–16]. Therefore, deregulation of NOD2 may affect individual’s cancer risk [14, 17]. There are different putative miRNA-binding sites within the 3′UTR of NOD2 gene identified by means of specialized algorithms (e.g., miRBase, miRanda, and PicTar) [13].

Our case–control study intended to evaluate the association between single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs3135500, in the 3′UTR of NOD2 with CRC risk in an Iranian population. This polymorphism is reported to be targeted by hsa-miR158, hsa-miR215, hsa-miR98, and hsa-miR573 [13].

We also investigate the probable relationship between some factors such as smoking, NSAID use, BMI, and physical activity with different alleles of this polymorphism.

Materials and methods

Study population and sample preparation

The study population composed of 88 patients and 88 controls. All the cases and controls were recruited from individuals referred to two referral centers in Isfahan Province, Iran between 2008 and 2011. Our patients were chosen from subjects with sporadic CRC, without familial history of CRC or any other related cancers. Influential factors such as smoking, NSAID use, BMI, and physical activity for all the subjects were recorded in a questionnaire. All subjects gave informed consent for the study, which was confirmed and approved by the University Ethical Committee. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples of each subject and quality and quantity of the extracted DNA was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectroscopy.

Selection of polymorphism

Previously identified miRSNPs in the 3′UTR of NOD2 gene [13] were carefully reviewed. On the basis of certain criteria such as minor allele frequency, rs3135500 was selected for our case–control analysis.

NOD2 genotyping

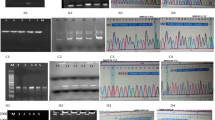

The genotyping of rs3135500 polymorphism was done by PCR–RFLP method. Using appropriate primer set (Table 1), the gene fragment that contained the selected polymorphism was PCR amplified. Subsequently, PCR products were digested with MboI restriction enzyme for the purpose of genotyping. To confirm our results based on PCR–RFLP method, around 10 % of the samples were randomly selected and subjected to direct sequencing.

Result

Our study population consisted of 88 patients (46 male and 42 female) and 88 non-cancer individuals (46 male and 42 female). Statistical analysis showed no major variances in the age, BMI, gender distribution, and smoking status between patients and controls (p > 0.05).

However, we found a significant difference in physical activity (p = 0.001) between case and control groups. Also individuals in control group were more aspirin or NSAID user compared with sporadic CRC cases (p = 0.002) (Table 2).

Genotype distribution in case and control groups was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Overall, the rs3135500 polymorphism, located in the 3′UTR of the NOD2 gene, was significantly associated with CRC risk in our study population (<0.001) (Table 3).

The frequencies of the GG, AG, AA genotypes in the control group were 39.8, 48.9, and 11.4 %, respectively, and the genotype frequencies in case group were 17, 47.7, and 35.2 %, respectively. This result demonstrated the significant association of AA genotype with risk of CRC in our study (adjusted OR 3.100, CI 1.621–5.930, p < 0.001). We also examined allelic frequency distribution between the control and case groups. According to our result, the frequency of the variant allele A among the case group was higher than that of control group, and we found that the A allele of the rs3135500 polymorphism was associated with an increase risk of CRC (adjusted OR 2.59, CI 1.68–3.98, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

We also found that our case group consumed less aspirin or NSAID compared with control group (13.6 vs. 33 %, p = 0.002). The Fisher’s test was further used to evaluate the association between rs3135500 polymorphism genotypes and aspirin or NSAID consumption. In the whole population, percentile of aspirin or NSAID consumers with AA, AG and GG genotypes were 12.2, 31.8, and 18 %, respectively (p = 0.003). In the case group, individuals with GG genotype used more aspirin or NSAID compared with AA+AG genotypes (33.3 vs. 9.6 %, adjusted OR 4.71, CI 1.25–17.76, p = 0.02). In the control group, individuals with AA+AG genotypes use more aspirin or NSAID compared with GG genotypes (47.2 vs. 11.4 %, adjusted OR 14 %, CI 0.05–0.47, p < 0.001) (Table 4).

We also used Mann–Whitney test for comparing physical activity between case and control groups. Significant difference in activity was found between case and control groups (p = 0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

Functional polymorphism in human DNA may affect susceptibility to diseases including cancers [18]. Several studies have proposed that functional polymorphism in the 3′UTR of cancer-related genes, which targeted by microRNAs, may affect the expression and function of the gene or miRNA and therefore may be significantly associated with cancer risk [4, 13, 19].

In this study, we evaluated the association between the CRC and rs3135500 polymorphism located in the 3′UTR of NOD2 gene among Iranian patients.

NOD2 is the key regulator of chronic inflammatory conditions. Chronic inflammation induces DNA damage, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis and so leading to tumorigenesis [20, 21]. Several studies proposed that polymorphisms in NOD2 have been associated with increased risk of CRC. For instance, association of three major NOD2 variants in its coding region, G908R, R702W, and 3020 ins C, have investigated in colorectal [15, 22] and gastric cancer cases [23] in different populations [22].

NOD2 gene is reported to be targeted by hsa-miR-158, hsa-miR-215, hsa-miR-98, and hsa-miR-573 [13]. Recent studies demonstrated hsa-miR98 [24] and hsa-miR215 [24, 25] functions as tumor suppressor. In this study, rs3135500 that is located in the 3′UTR of NOD2 gene was genotyped in sporadic CRC patients and their normal counterparts. No studies have been conducted on Iranian population yet, to evaluate the correlation of rs3135500 polymorphism with CRC risk. However, no studies have been conducted on the exact effect of rs3135500 on the miRNA–mRNA interaction in CRC. It appears that rs3135500 polymorphism change mRNA–miRNA interaction resulting in dysregulation of NOD2 gene.

Earlier studies have shown that let-7/miR-98 cluster, hsa-miR-143, and hsa-miR-145 are frequently down-regulated in malignancies of the breast, lung, thyroid, blood, GI tract, and genitourinary tract [26, 27]. On the basis of expression profiling experiment, various specific miRNAs are dysregulated in different type and stages of CRC [7, 8, 26, 28–30]. Different studies proposed that hsa-miR-215 [31] and hsa-miR-98 [32] decreased in CRC tumor tissues, and functions as tumor suppressor. Different levels of hsa-miR-215 correlated with clinical stage [31]. Similarly miRNA expression profile among different type of tumors demonstrated the involvement of microRNAs in the cellular pathways modified in tumorigenesis [26].

We found that the AA genotype of rs3135500 is significantly associated with increased risk of CRC (adjusted OR 3.100, CI 1.621–5.930, p < 0.001) and also the allele frequency of A was associated with an increase risk of CRC (adjusted OR 2.59, CI 1.68–3.98, p < 0.001). Therefore, it is assumed that AA genotype of rs3135500 may alter the risk of CRC in our population.

Numerous earlier studies suggesting that both aspirin and non-aspirin NSAID use is associated with a reduced risk of CRC [33, 34]. Other studies indicated that using aspirin after (or before) the diagnosis of CRC reduces CRC-specific mortality [34, 35]. According to our studies, individuals of our control group who have the risk allele A (AA+AG genotypes) consumed more aspirin or NSAID compared to GG genotypes (47.2 vs. 11.4 %, adjusted OR 14 %, CI 0.05–0.47, p < 0.001). It seemed that those who had the risk allele and used aspirin or NSAID had a reduced risk of CRC. These findings suggest that effectiveness of aspirin or NSAID in reduction of CRC risk is genotype dependent.

References

Bai Y-H, Lu H, Hong D, Lin C-C, Yu Z, Chen B-C. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol (WJG). 2012;18(14):1672.

Daraei A, Salehi R, Salehi M, Emami M, Jonghorbani M, Mohamadhashem F, et al. Effect of rs6983267 polymorphism in the 8q24 region and rs4444903 polymorphism in EGF gene on the risk of sporadic colorectal cancer in Iranian population. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):1044–9.

Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Safaee A, Zali MR. Prognostic factors in 1,138 Iranian colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(7):683–8.

Landi D, Gemignani F, Barale R, Landi S. A catalog of polymorphisms falling in microRNA-binding regions of cancer genes. DNA Cell Biol. 2008;27(1):35–43.

Chen K, Song F, Calin GA, Wei Q, Hao X, Zhang W. Polymorphisms in microRNA targets: a gold mine for molecular epidemiology. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(7):1306–11.

Liu C, Zhang F, Li T, Lu M, Wang L, Yue W, et al. MirSNP, a database of polymorphisms altering miRNA target sites, identifies miRNA-related SNPs in GWAS SNPs and eQTLs. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):661.

Faber C, Kirchner T, Hlubek F. The impact of microRNAs on colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2009;454(4):359–67.

Yang L, Belaguli N, Berger DH. MicroRNA and colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2009;33(4):638–46.

Fang Z, Rajewsky N. The impact of miRNA target sites in coding sequences and in 3′ UTRs. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18067.

Xiong F, Wu C, Chang J, Yu D, Xu B, Yuan P, et al. Genetic variation in an miRNA-1827 binding site in MYCL1 alters susceptibility to small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5175–81.

Mishra PJ, Mishra PJ, Banerjee D, Bertino JR. MiRSNPs or MiR-polymorphisms, new players in microRNA mediated regulation of the cell: introducing microRNA pharmacogenomics. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(7):853–8.

Eaden J, Abrams K, Mayberry J. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48(4):526–35.

Landi D, Gemignani F, Naccarati A, Pardini B, Vodicka P, Vodickova L, et al. Polymorphisms within micro-RNA-binding sites and risk of sporadic colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(3):579–84.

Kurzawski G, Suchy J, Kładny J, Grabowska E, Mierzejewski M, Jakubowska A, et al. The NOD2 3020insC mutation and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(5):1604–6.

Tian Y, Li Y, Hu Z, Wang D, Sun X, Ren C. Differential effects of NOD2 polymorphisms on colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(2):161–8.

Papaconstantinou I, Theodoropoulos G, Gazouli M, Panoussopoulos D, Mantzaris GJ, Felekouras E, et al. Association between mutations in the CARD15/NOD2 gene and colorectal cancer in a Greek population. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):433–5.

Liu J, He C, Xu Q, Xing C, Yuan Y. NOD2 polymorphisms associated with cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89340.

Abulí A, Bessa X, González JR, Ruiz-Ponte C, Cáceres A, Muñoz J, et al. Susceptibility genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer risk correlate with cancer phenotype. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):788–96.

Azimzadeh P, Romani S, Mohebbi SR, Mahmoudi T, Vahedi M, Fatemi SR, et al. Association of polymorphisms in microRNA-binding sites and colorectal cancer in an Iranian population. Cancer Genet. 2012;205(10):501–7.

Nakajima N, Kuwayama H, Ito Y, Iwasaki A, Arakawa Y. Helicobacter pylori, neutrophils, interleukins, and gastric epithelial proliferation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:S198–202.

Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. Inflammatory cytokines induce DNA damage and inhibit DNA repair in cholangiocarcinoma cells by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2000;60(1):184–90.

Tuupanen S, Alhopuro P, Mecklin JP, Järvinen H, Aaltonen LA. No evidence for association of NOD2 R702W and G908R with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(1):76–9.

Angeletti S, Galluzzo S, Santini D, Ruzzo A, Vincenzi B, Ferraro E, et al. NOD2/CARD15 polymorphisms impair innate immunity and increase susceptibility to gastric cancer in an Italian population. Hum Immunol. 2009;70(9):729–32.

Ye J-J, Cao J. MicroRNAs in colorectal cancer as markers and targets: recent advances. World J Gastroenterol (WJG). 2014;20(15):4288.

Feng Z, Zhang C, Wu R, Hu W. Tumor suppressor p53 meets microRNAs. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3(1):44–50.

Manne U, Shanmugam C, Bovell L, Katkoori VR, Bumpers HL. miRNAs as biomarkers for management of patients with colorectal cancer. Biomark Med. 2010;4(5):761–70.

Wang Y, Lee CG. MicroRNA and cancer—focus on apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(1):12–23.

Cekaite L, Rantala JK, Bruun J, Guriby M, Ågesen TH, Danielsen SA, et al. MiR-9,-31, and-182 deregulation promote proliferation and tumor cell survival in colon cancer. Neoplasia. 2012;14(9):868–IN21.

Huang Z, Huang D, Ni S, Peng Z, Sheng W, Du X. Plasma microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for early detection of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(1):118–26.

Schepeler T, Reinert JT, Ostenfeld MS, Christensen LL, Silahtaroglu AN, Dyrskjøt L, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic microRNAs in stage II colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6416–24.

Faltejskova P, Svoboda M, Srutova K, Mlcochova J, Besse A, Nekvindova J, et al. Identification and functional screening of microRNAs highly deregulated in colorectal cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(11):2655–66.

Parasramka MA, Dashwood WM, Wang R, Saeed HH, Williams DE, Ho E, et al. A role for low-abundance miRNAs in colon cancer: the miR-206/Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) axis. Clin Epigenet. 2012;4(1):16–26.

Vainio H, Morgan G, Kleihues P. An international evaluation of the cancer-preventive potential of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1997;6(9):749–53.

Ruder EH, Laiyemo AO, Graubard BI, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Cross AJ. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colorectal cancer risk in a large, prospective cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(7):1340–50.

Chia WK, Ali R, Toh HC. Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer—reinterpreting paradigms. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(10):561–70.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to the Vice Chancellor for Research, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, for financial support.

Conflict of interest

We declare that there is no any conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahangari, F., Salehi, R., Salehi, M. et al. A miRNA-binding site single nucleotide polymorphism in the 3′-UTR region of the NOD2 gene is associated with colorectal cancer. Med Oncol 31, 173 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0173-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0173-7