Abstract

Seizures and seizure-like activity may occur in patients experiencing aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Treatment of these events with prophylactic antiepileptic drugs remains controversial. An electronic literature search was conducted for English language articles describing the incidence and treatment of seizures after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage from 1980 to October 2010. A total of 56 articles were included in this review. Seizures often occur at the time of initial presentation or aneurysmal rebleeding before aneurysm treatment. Seizures occur in about 2% of patients after invasive aneurysm treatment, with a higher incidence after surgical clipping compared with endovascular repair. Non-convulsive seizures should be considered in patients with poor neurological status or deterioration. Seizure prophylaxis with antiepileptic drugs is controversial, with limited data available for developing recommendations. While antiepileptic drug use has been linked to worse prognosis, studies have evaluated treatment with almost exclusively phenytoin. When prophylaxis is used, 3-day treatment seems to provide similar seizure prevention with better outcome compared with longer-term treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Seizures and seizure-like phenomena are not uncommon after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). At the time of the acute presentation, frank tonic/clonic seizures can occur, as well as seizure-like tonic movements related to herniation or increased intracranial pressure [1–8]. Both generalized and focal seizures may also occur during hospitalization for SAH and during follow-up.

The significance of and appropriate treatment for seizures related to SAH are areas of debate. While antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may be prescribed to prevent seizures and additional neurological injury after SAH, well-designed, randomized, controlled trials to provide solid data to develop evidence-based practice guidelines are lacking. The need for routine antiepileptic drugs treatment after SAH and the appropriate duration of anticonvulsant prophylaxis are controversial; there are limited controlled data supporting benefits as well as the potential for medication-related side effects.

Methods

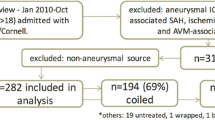

An electronic literature search was performed of the National Library of Medicine, EBSCO, EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Library from 1980 to October 2010 to identify articles addressing the incidence and significance of seizures in patients with SAH and the effect of prophylactic treatment. In press articles that were available to be viewed online prior to the cut-off of October 2010 were also included. Candidate articles were identified by searching titles and abstracts for the key word “subarachnoid hemorrhage” and at least one of the following additional key words: “seizures,” “epilepsy,” “convulsive status,” “non-convulsive status,” “convulsion,” “antiepileptic drug,” “anticonvulsant,” “phenytoin,” “levetiracetam,” or “carbamazepine.”

Abstracts for potential selection were screened to see whether they described studies that involved human subjects, and the full manuscript was published in English. Both original research and review articles were included. Studies addressing traumatic SAH were excluded. Selected articles were those that directly addressed the proposed areas of interest (seizure occurrence and AED prophylaxis). Following identification of articles to be included in this review, additional references were identified by reviewing citations provided in the list of references cited in each paper to determine additional studies likely to meet inclusion criteria. Original research studies were evaluated for quality of data and strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach [9].

Summary of the Pertinent Literature

A total of 56 papers were identified for this review. A sample of data from 23 representative original research studies are cataloged in Table 1, which describes study design, outcome, level of research, and balance of potential benefits versus risks [1, 2, 4, 5, 10–28]. In all but one case [18], quality of evidence was very low or low. None of the studies were able to be assigned a recommendation strength, due to insufficient data.

Incidence of Seizures

Seizures occurring at the time of SAH are called onset seizures. The reported incidence of onset seizures varies between 4 and 26% [1–6, 13, 24, 29, 30]. This wide variation in reported events is in part related to the occurrence of seizure-like tonic phenomena related to hyperextension that can occur secondary to herniation or increased intracranial pressure [1–6]. These events may be difficult to distinguish from true seizures. Often, the description of these events is provided by non-medical bystanders with insufficient background to differentiate tonic events from seizures.

Seizures occurring after hospital admission but prior to aneurysm treatment are often a symptom of rebleeding. Data from the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) indicate that pretreatment seizures often herald rebleeding [18]. Among the 2,143 SAH patients included in the ISAT sample, 14 patients (0.65%) suffered seizures after hospitalization but before treatment of the aneurysm. In 9 of these 14 cases, seizure was associated with rebleeding.

Seizure incidence after aneurysm treatment may vary based on treatment. In the ISAT sample, seizures occurred in 2.3% after treatment of the index aneurysm and until discharge [18]. The frequency of seizures after treatment and before discharge was doubled in patients treated with surgical clipping (3%) compared with those receiving endovascular treatment (1.4%) [18]. The difference in seizures frequency between the two treatment modalities was particularly marked in older patients. In a subgroup analysis of 278 patients > 65 years old in the ISAT cohort, seizures occurred in 0.7% of patients treated with coil embolization and in 12.9% of those treated with surgical clipping (P < 0.001) [31]. In the Intraoperative Hypothermia for Aneurysm Surgery Trial (IHAST), overall seizure incidence was similar among patients randomly assigned to intraoperative hypothermia (7%) or normothermia (6%) [32]. Seizures beginning > 2 weeks after surgery for SAH treated with aneurysm clipping are uncommon [33].

Seizures occurring during hospitalization have been linked to a variety of disease severity markers, with correlations found with poor neurological status at admission, prolonged loss of consciousness at presentation, middle cerebral artery aneurysm location, higher cisternal clot burden, rebleeding, and the presence of intracerebral hematomas, hydrocephalus, and cerebral ischemia [2, 4, 5, 10, 15, 17, 22, 26, 34–37]. These same risk factors have also been linked with late seizures occurrence [26, 38, 39]. Contrasting data exist about the correlation between in-hospital seizures and poor outcome. In a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from 527 patients with SAH, seizures occurring during hospitalization did not correlate with worse outcome [19]. These data suggested that seizures in patients with SAH are an indication of more severe disease rather than being an independent predictor of poorer outcome. Similar data were reported by Lin and coworkers in a retrospective study of 137 patients with SAH [25]. They found that higher-grade SAH on presentation was predictive of seizure, but the presence of seizures itself was not a significant predictor of prognosis after 1-year follow-up. Conversely, other studies have reported that seizures after SAH are associated with poor outcome [1, 40].

During the first year after discharge, the incidence of seizures is approximately 1.3% after endovascular treatment and 2.2% after surgery [18]. The risk of new-onset seizures after the first year remains low. While most authors have reported no statistically significant correlation between onset seizure (seizures occurring at the time of SAH) and late epilepsy [5, 15, 17, 25, 26, 35, 41], one study found onset seizures to be an independent risk factor for delayed (< 6 weeks) seizures [1].

There is a trend toward decreasing incidence of seizures after SAH over time [1, 12, 16, 22, 42]. This decreasing trend probably reflects changes in treatment strategies over time, such as the introduction of endovascular therapy [10, 22].

Non-Convulsive Seizures

Most incidence data for seizures in patients with aneurysmal SAH reflect clinically evident seizures consisting of either focal or generalized tonic/clonic activity. Non-convulsive electrical epileptiform activity may also occur after SAH. Non-convulsive seizures and status are not associated with clinically evident phenomena and have been reported after SAH, particularly in patients with poor neurological condition. Claassen and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of 29,998 patients, using data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database collected between 1994 and 2002 [2]. This study identified convulsive status epilepticus in about 0.2% of non-traumatic SAH patients [2]. Using continuous electroencephalography (cEEG) monitoring in patients with poor-grade SAH, researchers identified non-convulsive status epilepticus in 8 of 101 SAH patients treated in a neurological intensive care unit with unexplained coma or neurological deterioration [14]. They postulated that routine postoperative cEEG monitoring of patients with SAH who are at high risk for non-convulsive status epilepticus might permit earlier diagnosis and treatment to maximize treatment outcome. Claassen and colleagues subsequently performed a retrospective study of 756 patients with SAH who received cEEG [20]. Outcome was unfavorable in all patients with periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges, absence of sleep architecture, and electrographic status epilepticus, and in 92% of patients with non-convulsive status epilepticus. The authors concluded that the cEEG monitoring can provide prognostic information in poor-grade SAH patients. Despite the lack of evidence that cEEG monitoring improves outcome, clinicians often favor using this in SAH patients with depressed mental status to help diagnose non-convulsive seizures and dictate AED initiation [21, 35, 43, 44].

Anticonvulsants after SAH

AED prophylaxis after SAH is a common clinical practice [26, 27, 45]. No randomized controlled trials have investigated the safety and effectiveness of AEDs in SAH after aneurysmal rupture. Most recommendations on seizure prophylaxis after SAH are extrapolated from studies in patients after head injury or intracerebral hemorrhage, or patients with brain tumors [46–48]. Lack of data in aneurysmal rupture patients results in uncertainty regarding the need for AED prophylaxis, choice of drug, dosing, and duration of treatment. Because of the lack of evidence, use of AEDs in patients with SAH varies widely between institutions and physicians [22]. In an analysis of four randomized trials of tirilazad mesylate in SAH conducted worldwide between 1992 and 1997, 65% of patients received prophylactic AEDs. Those data contrast with results from a survey of 100 German neurosurgical departments about SAH management conducted in 2004 [49]. In that survey, AED prophylaxis was used routinely by only 4% of the physicians surveyed. The current uncertainty regarding the use of AEDs in SAH is reflected in the cautious wording of the most recent update of the guidelines of the American Heart Association published in 2009 that concluded that “the administration of prophylactic anticonvulsants may be considered in the immediate posthemorrhagic period (Class IIb, Level of evidence B)” [50]. A Cochrane review with the aim to assess the effects of AEDs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures after SAH is ongoing [51].

Negative Impact of AEDs on Outcome

Due to lack of data and evidence-based guidelines, AED treatment after SAH is determined predominately by the individual treating physician, with substantial variability among centers and countries worldwide. There is growing evidence to suggest that AEDs, and especially phenytoin, have a deleterious effect on outcome. A relationship between AED treatment after SAH and outcome was evaluated using pooled analysis of 3,552 patients with patients enrolled in the four trilizad trials [22]. In this sample, 65% of patients were treated with at least one AED, 8% with two AEDs, and 0.1% AEDs. Phenytoin was the most frequently prescribed AED (52.8%), followed by phenobarbital (18.7%) and carbamazepine (2.3%). AED usage varied dramatically among countries involved in the study and within the same country among different centers. In this subgroup analysis, 90% of patients underwent surgical clipping. Outcome was defined by the Glasgow Outcome Scale at 3 months, after adjusting for study center, World Federation of Neurosurgeons (WFNS) severity grade, patient age, and blood pressure. An unfavorable outcome was more common in patients treated with AEDs. Other secondary end points, including risk of clinical vasospasm, neurological worsening, cerebral infarction, and elevated temperature at day 8 of hospitalization, were also significantly more common in patients treated with AEDs. Interpreting data from this study is hampered by design limitations, such as the inability to assess duration of AED treatment or to distinguish between patients treated with prophylactic AEDs and patients administered AEDs after suffering a seizure. Nevertheless, this large analysis of patients prospectively enrolled in randomized studies supports safety concerns with routine use of AEDs in patients with SAH.

Naidech and coworkers also linked phenytoin treatment after SAH with neurological and cognitive recovery in a sample of 527 patients [19]. In this study, phenytoin burden was defined as the average serum phenytoin level multiplied by number of days between the first and last measurements, up to a maximum of 14 days. These authors linked prophylactic phenytoin with poor functional and cognitive outcome in a dose-dependent manner [19].

Most of the studies available on the issue of AEDs and seizures after SAH have analyzed the effects of phenytoin. Thus, the potential risks and benefits of newer generation AEDs are unknown and a potential topic for further studies [28, 35, 52, 53].

Duration of AEDs Treatment

When prophylactic AEDs are used in patients with SAH, evidence suggests that a short course of therapy may be as effective as a longer course. In 453 patients with spontaneous SAH managed homogeneously at a single center, a comparison was made between a routine 7-day prophylaxis and a shorter 3-day course [23]. The authors reported a significant reduction in phenytoin-associated complications (P = 0.002) without a difference in the rate of seizures using the shorter duration treatment [23]. In patients suffering a seizure during hospitalization, the literature describes continuation of AED therapy for a variable period (6 weeks to 6 months) [5, 11, 16, 19, 22, 23, 26, 33, 54, 55], although there are no strong data to support a particular treatment duration.

Conclusions

Seizures and seizure-like phenomena are not uncommon at the onset of SAH. In patients with an unsecured aneurysm, a seizure is often the expression of rebleeding. Patients at higher risk for developing seizures after SAH are patients with intraparenchymal hematomas, cerebral infarct, middle cerebral artery location, and hydrocephalus [49, 56, 57]. Patients with onset seizure do not appear to be at higher risk for subsequent seizures. Non-convulsive seizures should also be considered in SAH patients with unexplained coma or neurological deterioration. Patients undergoing endovascular embolization have a low risk of peri-procedural seizures [16, 18, 31]. AED prophylaxis remains controversial; however, phenytoin prophylaxis appears to be associated with worse outcome, especially when treatment is more prolonged.

References

Butzkueven H, Evans AH, Pitman A, et al. Onset seizures independently predict poor outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2000;55:1315–20.

Claassen J, Bateman BT, Willey JZ, et al. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus after nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage: the nationwide inpatient sample. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:60–4.

Hart RG, Byer JA, Slaughter JR, Hewett JE, Easton JD. Occurrence and implications of seizures in subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:417–21.

Pinto AN, Canhao P, Ferro JM. Seizures at the onset of subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol. 1996;243:161–4.

Rhoney DH, Tipps LB, Murry KR, Basham MC, Michael DB, Coplin WM. Anticonvulsant prophylaxis and timing of seizures after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2000;55:258–65.

Sundaram MB, Chow F. Seizures associated with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Can J Neurol Sci. 1986;13:229–31.

Riordan KC, Wingerchuk DM, Wellik KE, et al. Anticonvulsant drug therapy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a critically appraised topic. Neurologist. 2010;16:397–9.

Heros RC. Antiepileptic drugs and subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:251–2.

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490.

Hasan D, Schonck RS, Avezaat CJ, Tanghe HL, van Gijn J, van der Lugt PJ. Epileptic seizures after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:286–91.

Baker CJ, Prestigiacomo CJ, Solomon RA. Short-term perioperative anticonvulsant prophylaxis for the surgical treatment of low-risk patients with intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:863–70.

Olafsson E, Gudmundsson G, Hauser WA. Risk of epilepsy in long-term survivors of surgery for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a population-based study in Iceland. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1201–5.

Labovitz DL, Hauser WA, Sacco RL. Prevalence and predictors of early seizure and status epilepticus after first stroke. Neurology. 2001;57:200–6.

Dennis LJ, Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Emerson RG, Connolly ES, Mayer SA. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1136–43.

Claassen J, Peery S, Kreiter KT, et al. Predictors and clinical impact of epilepsy after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2003;60:208–14.

Byrne JV, Boardman P, Ioannidis I, Adcock J, Traill Z. Seizures after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with coil embolization. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:545–52.

Lin CL, Dumont AS, Lieu AS, et al. Characterization of perioperative seizures and epilepsy following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:978–85.

Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–17.

Naidech AM, Kreiter KT, Janjua N, et al. Phenytoin exposure is associated with functional and cognitive disability after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2005;36:583–7.

Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Frontera JA, et al. Prognostic significance of continuous EEG monitoring in patients with poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4:103–12.

Little AS, Kerrigan JF, McDougall CG, et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in patients suffering spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:805–11.

Rosengart AJ, Huo JD, Tolentino J, et al. Outcome in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with antiepileptic drugs. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:253–60.

Chumnanvej S, Dunn IF, Kim DH. Three-day phenytoin prophylaxis is adequate after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:99–102.

Szaflarski JP, Rackley AY, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Incidence of seizures in the acute phase of stroke: a population-based study. Epilepsia. 2008;49:974–81.

Lin YJ, Chang WN, Chang HW, et al. Risk factors and outcome of seizures after spontaneous aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:451–7.

Choi KS, Chun HJ, Yi HJ, Ko Y, Kim YS, Kim JM. Seizures and epilepsy following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: incidence and risk factors. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46:93–8.

Lewis S, Schmith A, Levetiracetam S. a potential alternative to phenytoin as first line prophylactic anti-epileptic therapy in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Epilepsia. 2009;50:124.

Shah D, Husain AM. Utility of levetiracetam in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Seizure. 2009;18:676–9.

Berre J, Hans P, Puybasset L, et al. Epilepsy in patients suffering from severe subarachnoid haemorrhage. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2005;24:739–41.

Huff JS, Perron AD. Onset seizures independently predict poor outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2001;56:1423–4.

Ryttlefors M, Enblad P, Kerr RS, Molyneux AJ. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling: subgroup analysis of 278 elderly patients. Stroke. 2008;39:2720–6.

Todd MM, Hindman BJ, Clarke WR, Torner JC. Mild intraoperative hypothermia during surgery for intracranial aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:135–45.

Buczacki SJ, Kirkpatrick PJ, Seeley HM, Hutchinson PJ. Late epilepsy following open surgery for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1620–2.

Bidzinski J, Marchel A, Sherif A. Risk of epilepsy after aneurysm operations. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;119:49–52.

Gilmore E, Choi HA, Hirsch LJ, Claassen J. Seizures and CNS hemorrhage: spontaneous intracerebral and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurologist. 2010;16:165–75.

Keranen T, Tapaninaho A, Hernesniemi J, Vapalahti M. Late epilepsy after aneurysm operations. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:897–900.

Garrett MC, Komotar RJ, Starke RM, Merkow MB, Otten ML, Connolly ES. Predictors of seizure onset after intracerebral hemorrhage and the role of long-term antiepileptic therapy. J Crit Care. 2009;24:335–9.

O’Laoire SA. Epilepsy following neurosurgical intervention. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1990;50:52–4.

Liu KC, Bhardwaj A. Use of prophylactic anticonvulsants in neurologic critical care: a critical appraisal. Neurocrit Care. 2007;7:175–84.

Citerio G, Gaini SM, Tomei G, Stocchetti N. Management of 350 aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhages in 22 Italian neurosurgical centers. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1580–6.

Shaw MD. Post-operative epilepsy and the efficacy of anticonvulsant therapy. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1990;50:55–7.

Mayberg MR, Batjer HH, Dacey R, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1994;25:2315–28.

Rinkel GJ, Klijn CJ. Prevention and treatment of medical and neurological complications in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Pract Neurol. 2009;9:195–209.

Varelas PN, Spanaki M. Management of seizures in the critically ill. Neurologist. 2006;12:127–39.

Zubkov AY, Wijdicks EF. Antiepileptic drugs in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Rev Neurol Dis. 2008;5:178–81.

Temkin NR, Dikmen SS, Wilensky AJ, Keihm J, Chabal S, Winn HR. A randomized, double-blind study of phenytoin for the prevention of post-traumatic seizures. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:497–502.

North JB, Penhall RK, Hanieh A, Frewin DB, Taylor WB. Phenytoin and postoperative epilepsy. A double-blind study. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:672–7.

North JB, Penhall RK, Hanieh A, Hann CS, Challen RG, Frewin DB. Postoperative epilepsy: a double-blind trial of phenytoin after craniotomy. Lancet. 1980;1:384–6.

Sakowitz OW, Raabe A, Vucak D, Kiening KL, Unterberg AW. Contemporary management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in Germany: results of a survey among 100 neurosurgical departments. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:137–45.

Bederson JB, Connolly ES Jr, Batjer HH, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025.

Marigold RGA, Tiwari D, Kwan J. Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures after subarachnoid haemorrhage (Protocol). Cochrane Library 2010:1–8.

Szaflarski JP, Sangha KS, Lindsell CJ, Shutter LA. Prospective, randomized, single-blinded comparative trial of intravenous levetiracetam versus phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12:165–72.

Wong GK, Poon WS. Use of phenytoin and other anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2005;36:2532.

Haley EC Jr, Kassell NF, Apperson-Hansen C, Maile MH, Alves WM. A randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial of tirilazad mesylate in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a cooperative study in North America. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:467–74.

Klimek M, Dammers R. Antiepileptic drug therapy in the perioperative course of neurosurgical patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:564–7.

Rose FC, Sarner M. Epilepsy after ruptured intracranial aneurysm. Br Med J. 1965;1:18–21.

Diringer MN. Management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:432–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The Participants in the International Multi-disciplinary Consensus Conference: Michael N. Diringer, Thomas P. Bleck, Nicolas Bruder, E. Sander Connolly, Jr., Giuseppe Citerio, Daryl Gress, Daniel Hanggi, J. Claude Hemphill, III, MAS, Brian Hoh, Giuseppe Lanzino, Peter Le Roux, David Menon, Alejandro Rabinstein, Erich Schmutzhard, Lori Shutter, Nino Stocchetti, Jose Suarez, Miriam Treggiari, MY Tseng, Mervyn Vergouwen, Paul Vespa, Stephan Wolf, Gregory J. Zipfel.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lanzino, G., D’Urso, P.I., Suarez, J. et al. Seizures and Anticonvulsants after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 15, 247–256 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-011-9584-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-011-9584-x