Abstract

Neonatal herpes simplex viral infections are rare in the setting of appropriate prenatal care; however, under circumstances where prenatal care is not delivered, these infections can lead to significant disease. We report a fatal case of herpes simplex virus with severe herpes hepatitis in a 14-day old male neonate. The clinical history was limited and nonspecific, however there was no prenatal care and a known history of drug abuse in the family. Autopsy revealed extensive necrosis and hemorrhage of the liver and cerebellum. Histologically, the liver revealed viral intranuclear ground glass inclusions, characteristic of herpes virus. Immunohistochemistry for herpes simplex virus performed on the both the liver and cerebellum showed strong diffuse staining in the liver and negative staining in the cerebellum. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection is a disease of low prevalence with significant morbidity and mortality, and an exceptionally high rate of fatality in those with disseminated disease with associated fulminant hepatic failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Case report

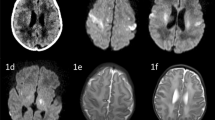

A 14-day old male neonate was found unresponsive in his crib after reportedly having mild respiratory distress and changes in feeding habits. There was no known prenatal care, the decedent was born via uncomplicated vaginal delivery, and the family had a history of drug abuse. Investigation of the scene demonstrated a safe crib environment. At autopsy, there was no evidence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation efforts or traumatic injury. Internal examination revealed extensive necrosis and hemorrhage of the liver (Fig. 1) and cerebellum (Fig. 2), pulmonary congestion, and a small sanguineous peritoneal effusion. The cardiac exam was unremarkable.

Microscopic examination revealed severe parenchymal necrosis and intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the hepatic (Fig. 3) and cerebellar parenchyma (Fig. 4) as well as viral intranuclear inclusions (Cowdry type A inclusion bodies) in the liver (Fig. 5). The heart demonstrated severe interstitial edema with acute inflammation and focal epicardial hemorrhage, but no viral inclusions were identified. Immunohistochemistry for herpes simplex virus (HSV) was performed and showed strong, diffuse nuclear staining in the liver (Fig. 6) and negative staining in the cerebellum. Postmortem toxicology was positive for caffeine, which was noncontributory to death. Death was due to herpes viremia with severe herpes hepatitis.

Discussion

Neonatal disseminated HSV infection is a sepsis-like condition associated with high mortality rates if not appropriately treated, and while it is a well recognized entity, is a relatively rare disease with an estimated incidence of 9.9–12.1 neonatal infections per 100,000 live births in the United States [1, 2]. Interestingly, South Carolina, the setting for our case, has a high incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) exceeding national averages [3]. The important finding in the reported case was extensive, diffuse involvement of the liver. Although the immunohistochemistry did not support the diagnosis of cerebellar involvement by HSV, there was clear evidence of cerebellar disease by gross examination and light microscopy, with extensive hemorrhage and necrosis. Additionally, herpes hepatitis with fulminate hepatic failure is occasionally the only finding of dissemintated disease, and is often fatal by the time of diagnosis or before transplantation can be achieved [4,5,6].

Infection can be caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2; and, HSV-1 and HSV-2 are now both common causes of genital infections. IHC for HSV alone cannot distinguish between HSV-1 or HSV-2 disease and there is at least a small proportion of cases that have obvious viral cytopathologic effects with negative or rare IHC positive cells [7,8,9]. The diagnosis can also be made by in situ hybridization or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on paraffin embedded tissue. Nicoll et al. reported two autopsy cases of neonatal HSV in which typing of the virus was achieved by PCR, and IHC was used to confirm dissemination of virus in the tissue [8]. Dye and Simmons reported a fatal case of HSV-1 infection in a neonate in which the disease was spread post-partum by an infected individual [4]. The liver was primarily involved, with viral intranuclear inclusions present in the remaining viable hepatocytes, and IHC for HSV confirmed the diagnosis. The mother was then tested for HSV-1 and HSV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies which were negative, and a PCR for HSV-1 on liver tissue from the decedent was positive; this allowed for further subtyping in order to better characterize the correct virus to ultimately elucidate the mode of transmission.

The utility of IHC, as well as PCR, should be determined on a case by case basis. The use of IHC is generally not necessary if the viral cytopathologic effects are clearly identifiable on H&E, however it can be a useful aid in diagnosis [9]. The absence of staining in the cerebellum in our case likely represents a separate pathologic process related to but not directly caused by HSV infection, such as a coagulopathic or septic process. PCR should not be performed without a high index of suspicion (i.e. involvement on light microscopy). The use of PCR is lower yield, as the subtyping of virus is less significant with the advancement of HSV-1 related genital infections. The distribution of organ involvement as well as the numerous intranuclear Cowdry type A inclusion bodies found in the tissue sections, which are a non-specific but sensitive finding, are diagnostic of neonatal HSV in this case, which was then confirmed by IHC. Disseminated HSV should always be considered as a possibility, especially in neonates with central nervous system, hepatic, pulmonary, or multi-organ disease processes. The differential diagnoses to be considered in those with disseminated disease are broad and include other viral causes, but identification of viral cytopathologic effects (Cowdry A type inclusions bodies) are considered diagnostic. We report this case to express the need for increased awareness of local and regional trends in STIs when assigning cause of death to neonates as well as the gross findings, histologic findings and additional studies available to aid in diagnosis of neonatal HSV.

References

Kimberlin DW. Herpes simplex virus infections of the newborn. Semin Perinatol. 2007;31:19–25.

Lao S, Flagg EW, Schillinger JA. Incidence and characteristics of neonatal herpes: comparison of two population-based data sources, new York City, 2006–2015. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:125–31.

Orekoya O, White K, Samson M, Robillard AG. The South Carolina comprehensive health education act needs to be amended. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1950–2.

Dye DW, Simmons GT. Fatal herpes virus type I infection in a newborn. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2010;31:89–91.

Verma A, Dhawan A, Zuckerman M, Hadzic N, Baker AJ, Mieli-Vergani G. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection presenting as acute liver failure: prevalent role of herpes simplex virus type I. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:282–6.

Egawa H, Inomata Y, Nakayama S, Matsui A, Yamabe H, Uemoto S, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to herpes simplex virus infection in a neonate: a case report of successful treatment with liver transplantation and perioperative acyclovir. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:513–5.

Looker KJ, Magaret AS, May MT, Turner KM, Vickerman P, Newman LM, et al. First estimates of the global and regional incidence of neonatal herpes infection. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e300–9.

Nicoll J, Love S, Burton P, Berry P. Autopsy findings in two cases of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection: detection of virus by immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization and the polymerase chain reaction. Histopathology. 1994;24:257–64.

Solomon IH, Hornick JL, Laga AC. Immunohistochemistry is rarely justified for the diagnosis of viral infections. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017;147:96–104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and animal participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent in this case report in compliance with South Carolina ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Basinger, J.M., Fiester, S.E. & Fulcher, J.W. Mortality from neonatal herpes simplex viremia causing severe hepatitis. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 15, 663–666 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-019-00147-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-019-00147-w