Abstract

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms grade 3, all of them with >20% Ki-67, can be heterogeneous on the basis of their morphological features, comprising well and poorly differentiated neoplasms; the former are named tumors and the latter carcinomas. Several papers about gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms grade 3 heterogeneity have been reporting over the last years by clinicians and pathologists, indicating that the differential diagnosis between named tumors grade 3 and named carcinomas grade 3 may be relevant in defining a different approach in terms of characterization of disease, staging, and treatment. To well define the sub-type of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms grade 3 pathologist’s expertise in recognizing tumor morphology, immunohistochemical, and molecular techniques were reported remarkable. Although current evidence about grade 3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms heterogeneity is still far from producing validated specific therapies for specific subcategories, the hypotheses generated from the several retrospective analyses published so far on this topic represent solid bases for designing prospective therapeutic clinical trials in homogenous clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The incidence of Grade (G) 3 Gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) has increased over the last decades [1, 2]. Furthermore, in the largest epidemiological Italian series from AIRTUM (Italian association of tumor registry), poorly-differentiated (PD) GEP NENs showed an unexpected higher incidence than well-differentiated (WD) [3] NENs. This result seems in contrast with clinical practice; the methods applied, notably different ICD-O-3 codes, may have conditioned the results.

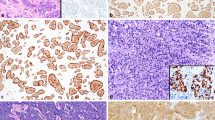

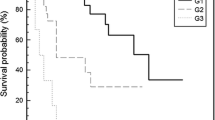

The G3 GEP NENs category has been extensively investigated over the last years [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Several reports remarked that some GEP NENs defined as G3 on the basis of their Ki-67 level in accordance with the 2010 WHO classification [12] were actually WD rather than PD and they correlated with a significantly better survival compared with PD. This new entity, named “Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) G3”, has been forecasted to be included in the new pancreatic NENs classification [13]. Poorly differentiated pancreatic GEP NENs will be defined as neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) G3. Beyond tumor differentiation (WD vs. PD), even Ki-67 level (21–55% vs. >55%) has been reported as a factor able to separate different populations in terms of survival [14]. These data are important not only from a prognostic point of view but also for their implications in clinical practice [8, 15, 16].

On the basis of the aforementioned considerations, it is clear that each pathologist reporting a G3 GEP NEN should describe both tumor differentiation and Ki-67. However, while the assessment of Ki-67 can be standardized provided that the WHO indications are followed [12], tumor differentiation evaluation is less reproducible [17], especially in the absence of a specific pathology training.

When the distinction between WD and PD is not possible even after an expert review, the use of specific immune-histochemical markers, such as TP53, Rb1 and somatostatin receptor type 2 (SSTR2A) and 5 (SSTR5), can be helpful, as suggested by some authors [3, 17,18,19]. Loss of TP53 and Rb1 oncosuppressor function is associated with PD phenotype, whereas expression of SSTR2A and 5 is indicative of WD. However, an inconsistency between molecular biomarkers and tumor differentiation in a small subset of patients has been reported [18]. These controversial issues imply that both morphological and/or molecular approaches may have limitations, therefore we strongly suggest that each controversial case should be reviewed and discussed within a multi-specialist team for an appropriate therapeutic decision.

Although from a prognostic point of view it looks quite clear that the G3 GEP NENs category should be differentiated in separate sub-categories on the basis of tumor differentiation and Ki-67, it is less clear how much these factors alone can affect therapeutic choices. To date, several studies focused on therapeutic approaches accordingly to WD or PD G3 GEP NENs. However a few of them are uniquely based on the diagnostic report, lacking a central pathological and molecular revision, which may result in limited reproducibility, [6, 8] while others focused on a thourough pathology characterization without clinical and therapeutic information [17, 18]. Current evidence about G3 GEP NENs heterogeneity is still far from producing validated specific therapies for specific sub-categories, however it represents a good basis to suggest on one hand a different clinical approach for WD vs. PD G3 GEP NENs and on the other hand to design prospective therapeutic clinical trials on solid hypotheses. Unfortunately the design of several prospective ongoing or incoming clinical trials on G3 GEP NENs could not lead to definitive conclusions.

The ongoing NORDIC study with everolimus and temozolomide (NCT02248012) is a first-line phase II and uses one biologic together with one chemotherapeutic agent. Therefore, although investigating a well defined sub-category (20–55% Ki-67) it will not clarify whether this therapy is superior to platinum/etoposide and biological therapy is better than chemotherapy. A randomized design with pre-planned analyzes of sub-categories would have allowed to draw some clinical conclusions. Likewise the US trial with modified FOLFIRINOX is a phase II and it is enrolling all GEP NENs with >20% Ki-67 and/or 20 mitoses/10 high power fields without specifying if a central pathology review is planned and if tumor differentiation and/or Ki-67 level sub-categories will be evaluated (NCT03042780). More relevant to the clinical practice is the ongoing US randomized phase II trial comparing cisplatin/etoposide with capecitabine/temozolomide in patients with 20–100% Ki-67 advanced GEP NENs. Small-cell diseases are excluded; a centralized pathology review and a correlation between tumor differentiation (WD vs. PD) and clinical outcome has been planned (NCT02595424).

The new immune check point inhibitors, which showed efficacy in several types of neoplasms, were not extensively investigated in NENs so far. However the G3 GEP NENs can be considered for inclusion in some ongoing clinical trials. Some of them are specific for NENs not requiring a molecular prescreening (NCT02955069), whereas some others are based on microsatellite instability (MSI) or mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency detection. By means of PCR or IHC of MMR proteins an MSI was reported in around 10% of GEP NENs, mainly colorectal [19, 20].

Until we will have definite evidence about the efficacy of a therapy instead of another it is recommended that each clinician translates the current evidence into a cautious and thoughtful clinical approach to patients with a >20% Ki-67 GEP NEN, notably availing him/herself of other tools, such as clinical behavior of the disease, molecular imaging and clinical status of the patient and using clinical judgment.

References

E. Leoncini, P. Boffetta, M. Shafir, K. Aleksovska, S. Boccia, G. Rindi, Increased incidence trend of low-grade and high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine (2017). doi:10.1007/s12020-017-1273-x

A. Dasari, C. Shen, D. Halperin, B. Zhao, S. Zhou, Y. Xu et al., Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. (2017). doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589

A.W. Group, S. Busco, C. Buzzoni, S. Mallone, A. Trama, M. Castaing et al., Italian cancer figures—report 2015: the burden of rare cancers in Italy. Epidemiol. Prev. 40(1 Suppl 2), 1–120 (2016). doi:10.19191/EP16.1S2.P001.035

O. Basturk, Z. Yang, L.H. Tang, R. Hruban, C. McCall, V. Adsay et al., Increased (>20%) Ki67 proliferation index in morphologically well differentitated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) correlates with decreased overall survival. Mod. Pathol. 26(Abstract #1761), 463A (2013)

O. Basturk, Z. Yang, L.H. Tang, R.H. Hruban, V. Adsay, C.M. McCall et al., The high-grade (WHO G3) pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor category is morphologically and biologically heterogenous and includes both well differentiated and poorly differentiated neoplasms. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 39(5), 683–690 (2015). doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000408

M. Heetfeld, C.N. Chougnet, I.H. Olsen, A. Rinke, I. Borbath, G. Crespo et al., Characteristics and treatment of patients with G3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 22(4), 657–664 (2015). doi:10.1530/ERC-15-0119

M. Milione, P. Maisonneuve, A. Pellegrinelli, S. Pusceddu, G. Centonze, F. Dominoni et al., Loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) as a prognostic factor in advanced ileal well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrine (2016). doi:10.1007/s12020-016-1180-6

H. Sorbye, S. Welin, S.W. Langer, L.W. Vestermark, N. Holt, P. Osterlund et al., Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the NORDIC NEC study. Ann. Oncol. 24(1), 152–160 (2013). doi:10.1093/annonc/mds276

F.L. Velayoudom-Cephise, P. Duvillard, L. Foucan, J. Hadoux, C.N. Chougnet, S. Leboulleux et al., Are G3 ENETS neuroendocrine neoplasms heterogeneous? Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 20(5), 649–657 (2013). doi:10.1530/ERC-13-0027

F. Grillo, M. Albertelli, F. Annunziata, M. Boschetti, A. Caff, S. Pigozzi et al., Twenty years of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: is reclassification worthwhile and feasible? Endocrine 53(1), 58–62 (2016). doi:10.1007/s12020-015-0734-3

D.S. Klimstra, Reassessing the grade of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine 53(1), 4–6 (2016). doi:10.1007/s12020-016-0966-x

G.A.R. Rindi, F.T. Bosman, C. Capella, D.S. Klimstra, G. Klöppel, P. Komminoth, E. Solcia. Nomenclature and classification of digestive neuroendocrine tumors. in WHO Classification of tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon ed. by F.C.F. Bosman, R. Hruban, N. Theise (International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, 2010)

G. Klöppel. On the value of Ki-67 in the prognostic grading of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: an update. (USCAP, 2017) San Antonio, Texas. Accessed 4–10 March 2017

M. Milione, P. Maisonneuve, F. Spada, A. Pellegrinelli, P. Spaggiari, L. Albarello et al., The clinicopathologic heterogeneity of grade 3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: morphological differentiation and proliferation identify different prognostic categories. Neuroendocrinology 104(1), 85–93 (2017). doi:10.1159/000445165

N. Fazio, M. Milione, Heterogeneity of grade 3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas: New insights and treatment implications. Cancer Treat. Rev. 50, 61–67 (2016). doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.08.006

R. Garcia-Carbonero, H. Sorbye, E. Baudin, E. Raymond, B. Wiedenmann, B. Niederle et al., ENETS consensus guidelines for high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology 103(2), 186–194 (2016). doi:10.1159/000443172

M. Milione, P. Maisonneuve, F. Spada, A. Pellegrinelli, P. Spaggiari, L. Albarello et al., The clinicopathologic heterogeneity of grade 3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: morphological differentiation and proliferation identify different prognostic categories. Neuroendocrinology 104(1), 85–93 (2016). doi:10.1159/000445165

L.H. Tang, O. Basturk, J.J. Sue, D.S. Klimstra, A practical approach to the classification of WHO grade 3 (G3) well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (WD-NET) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (PD-NEC) of the pancreas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40(9), 1192–1202 (2016). doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000662

D.M. Girardi, A.C.B. Silva, J.F.M. Rego, R.A. Coudry, R.P. Riechelmann, Unraveling molecular pathways of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastroenteropancreatic system: A systematic review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 56, 28–35 (2017). doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.04.002

N. Sahnane, D. Furlan, M. Monti, C. Romualdi, A. Vanoli, E. Vicari et al., Microsatellite unstable gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas: a new clinicopathologic entity. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 22(1), 35–45 (2015). doi:10.1530/ERC-14-0410

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Massimo Milione and Nicola Fazio equally participated in the discussion of evidence and letter preparation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milione, M., Fazio, N. G3 GEP NENs category: are basic and clinical investigations well integrated?. Endocrine 60, 28–30 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1365-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1365-7