Abstract

Background

The ability of injection of corticosteroids into the subacromial space to relieve pain ascribed to rotator cuff tendinosis is debated. The number of patients who have an injection before one gets relief beyond what a placebo provides is uncertain.

Questions/purposes

We asked: (1) Do corticosteroid injections reduce pain in patients with rotator cuff tendinosis 3 months after injection, and if so, what is the number needed to treat (NNT)? (2) Are multiple injections better than one single injection with respect to pain reduction at 3 months?

Methods

We systematically searched seven electronic databases for randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid injection for rotator cuff tendinosis compared with a placebo injection. Eligible studies had at least 10 adults and used pain intensity as an outcome measure. The Hedges’s g as adjusted pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) (which expresses the size of the intervention effect in each study relative to the total variability observed among pooled studies) and NNT were calculated at assessment points less than 1 month, 1–2 months, and 2–3 months. The protocol of this study was registered at the international prospective register of systematic reviews. Eleven studies of 726 patients satisfied our criteria for data pooling. Three studies containing 292 patients used repeat injections. A random effects model was used owing to substantial heterogeneity among studies. The funnel plot indicated the possibility of some missing studies, but Orwin’s fail-safe N and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill suggested that missing studies would not significantly affect the results.

Results

Corticosteroid injection did not reduce pain intensity in adult patients with rotator cuff tendinosis more than a placebo injection at the 3-month assessment. A small transient pain relief occurred at the assessment between 4 and 8 weeks with a SMD of 0.52 (range, 0.27–0.78) (p < 0.001). At least five patients must be treated for one patient’s pain to be transiently reduced to no more than mild. Multiple injections were not found to be more effective than a single injection at any time.

Conclusions

Corticosteroid injections provide—at best—minimal transient pain relief in a small number of patients with rotator cuff tendinosis and cannot modify the natural course of the disease. Given the discomfort, cost, and potential to accelerate tendon degeneration associated with corticosteroids, they have limited appeal. Their wide use may be attributable to habit, underappreciation of the placebo effect, incentive to satisfy rather than discuss a patient’s drive toward physical intervention, or for remuneration, rather than their utility.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rotator cuff tendinosis—the chronic degeneration of a tendon without inflammation—is an expected part of human aging and the most common cause of shoulder pain [12]. Tendinosis encompasses many commonly used terms including “impingement,” “rotator cuff fraying,” “partial thickness tears,” and “tendinitis.” Often, tendinosis is asymptomatic, but in cases of symptomatic tendinosis, a corticosteroid injection into the subacromial space is a palliative treatment option [36]. The reasons for wide use of corticosteroid injections for rotator cuff tendinopathy may include training or habit, to satisfy the patient’s desire to intervene, for remuneration, and other factors, but it is not clear that corticosteroid injections outperform placebo injections. The effectiveness of corticosteroid injections for pain relief in patients with rotator cuff tendinosis is debated despite numerous prospective randomized trials and several systematic reviews [5, 15, 24, 25, 27, 36, 50]. The first four systematic reviews regarding this topic did not conduct a meta-analysis [5, 24, 32, 50]. The results of two meta-analyses [15, 24] reached different conclusions.

Since the last systematic review in 2010 by Coombes et al. [15], there are four new prospective randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid injections for rotator cuff tendinosis [31, 37, 44, 45]. Furthermore, previous systematic reviews characterized the effect size with pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) alone and categorized the SMD values, both of which provide information of limited use to clinicians and patients [13, 16, 34].

The number needed to treat (NNT; the number of patients who have an injection before one gets relief beyond what a placebo provides) is a better measure of treatment effectiveness and remains uncertain for corticosteroid injections for rotator cuff tendinosis. For dichotomous outcomes, it is calculated as the inverse of the difference between the event rate in the experimental group (experimental event rate) and event rate in the control group (control event rate [CER]). We calculated the NNT as the number of patients who need to have an injection for one patient to experience a decrease in their VAS to 3.4 or lower.

Our specific study questions were: (1) Do corticosteroid injections reduce pain in patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy during the 3-month evaluation, and if so, what is the NNT? (2) Are multiple injections better than one single injection with respect to pain reduction during the 3-month evaluation?

Material and Methods

In accordance with the published guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Appendix 1. Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR ®.), this meta-analysis was designed to compare the pooled SMD of VAS pain in adult patients with rotator cuff tendinosis treated with a local corticosteroid injection versus placebo injection. We considered the following descriptors as tendinosis: “impingement,” “tendinitis,” and “tendinopathy” (Appendix 2. Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR ®.). The protocol of the study was registered before the data collection and is accessible at the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO 2015:CRD42015025964) [40].

Studies were eligible if there was (1) a randomized controlled trial of corticosteroid injection treatment for rotator cuff tendinosis compared with a placebo injection (either normal saline or local anesthetic); (2) at least 10 adults were included in the trial; (3) a full-text article was available; (4) a VAS for pain was used as an outcome measure; and (5) patients were evaluated at least 1 week after injection. A study was excluded if the article was not an original study. Animal studies were excluded.

On August 20, 2015, we searched EMBASE®, PubMed Publisher, MEDLINE Ovid®SP, CINAHL (EBSCO), Web of Science™, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Central using the search strategy described in the Appendix 2. References of relevant articles were checked for additional articles and all bibliographies of the included articles were hand-searched to identify further relevant literature. Moreover, emails were sent to the corresponding authors of included studies to seek and confirm any other published or unpublished data.

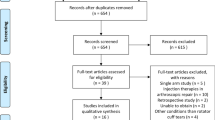

Two investigators (AM, JJC) screened studies independently for eligibility. Studies that had at least one outcome as a VAS pain score were included. After removal of duplicates, we identified 5442 studies, of which 82 were potentially eligible based on their title and abstract (Fig. 1). We also found five more studies using additional data sources: one by contacting authors and four from previous systematic reviews [15, 17]. After review of full text, 72 articles did not fulfill the inclusion criteria.

Fourteen randomized controlled trials met inclusion criteria for systematic review (Table 1) (Appendix 3. Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR ®.) [1–4, 8, 32, 37, 38, 44–47, 51, 52]. We excluded three studies from the meta-analysis owing to a Jadad score below three, leaving 11 studies for meta-analysis [1–4, 32, 38, 44–47, 51]. The average sample size of these studies was 63 patients (range, 25–107), with an average age of the patients of 54 years (range, 48–58 years). Two studies used saline as a placebo [47, 52] and 11 used lidocaine. Triamcinolone was used in seven trials [1, 8, 32, 37, 44–46] (most commonly a single 40-mg dose; range, 10–80 mg). Methylprednisolone was used in six trials, most commonly a 40-mg dose (range, 25–80 mg) [2, 4, 38, 47, 51, 52]. In one trial, patients received a 6 mg injection of betamethasone [3]. Two of the four studies [3, 4, 8, 44] that assessed patients for longer than 3 months found a reduction in pain with corticosteroid injection [4, 8].

We developed a data extraction sheet based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group’s data extraction template. Two independent reviewers (AM, JJC) extracted data and coded them in the predetermined data sheet. The following data were extracted: journal name, first author, year of publication, study design, country in which the study was performed, number of included patients, percentage of male participants, mean age, duration of followup (months), patients lost to followup (eg, withdrawn, dropout), type of clinical outcome, mean VAS of pain, and SD. We did not try to obtain raw data or confirm synthesized data from investigators of the included studies.

We analyzed pain intensity the first, second, and third months after injection. The first month was defined as less than 4 weeks, the second month was between 4 and 8 weeks, and the third month was between 8 and 12 weeks.

Two collaborators (AM, JJC) independently appraised the included studies using The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. For meta-analyses, the methodologic quality of the studies was graded based on the Jadad scale for randomized controlled trials [33]. A quality score of 3 or greater is considered high quality. Only high-quality trials were included in this meta-analysis. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two collaborators (AM, JJC) to reach final consensus.

Statistical Analysis

We used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2.2064 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) software to perform the meta-analysis. The mean VAS, SD before and after the corticosteroid injection, and the number of patients in the intervention and control groups were used to calculate the Hedges’s g for each study. The Hedges’s g, an adjusted SMD, is a measure of effect size for studies with continuous outcome. It indicates the size of the intervention effect in each study relative to the variability observed among studies by difference of means in study groups divided by the pooled SD. If data were presented in 95% CIs, the SD is calculated with the following formula: SD = 95% CI/1.96 × √n. When the median and range were reported for continuous outcomes, the mean and SD were estimated by assuming that the mean is equivalent to the median and that the SD is a quarter of the range. If no SD was given, the SD was estimated as ½ of the mean value. Hedges’s g also can be calculated with the proportion of “cured” or “improved “patients in each study arm or with the mean difference correspondent p values before and after a corticosteroid injection.

To assess publication bias, a funnel plot was drawn (Fig. 2). Visual assessment of the funnel plot indicated a possibility of missing studies on the left side of the funnel plot. However, fail-safe N [48] showed 82 missing studies are needed to change the results and Orwin’s fail-safe N [42] showed at least nine missing studies are needed to bring the Hedges’s g below the trivial value. To address heterogeneity among individual included studies, we calculated Cochran’s Q statistic. A p value of 0.10 or less was set to determine statistical significance [18]. Because of concerns regarding the power of the Q statistic, the I2 statistic was reported [18]. I2 values are classified to represent low (0%–25%), moderate (25%–50%), substantial (50%–75%), or considerable (> 75%) inconsistency [30].

There was substantial heterogeneity among the clinical trials, which was not explained in sensitivity analysis by year of publication, quality assessment (Jadad scale), type of placebo, or multiple versus single injection, therefore we used a random effects model for meta-analysis. This suggests a notable potential for bias.

We calculated Hedges’s g, which is the bias-adjusted estimate of the SMD for each study. Hedges’s g is an effect size estimator for continuous outcomes and is calculated by dividing the mean difference by the pooled SD [29]. We report the Hedges’s g with its 95% CI (by study size and SD) for individual studies and the pooled SMD, 95% CI, and standardized error. We report study outcome using pooled SMD (Hedges’s g) and standardized error. The studies had substantial heterogeneity with an I2 value of 60%–67% in different assessment points, and therefore, a random effect modeling was used for meta-analysis. The SMD is considered to represent trivial (< 0.20), small (0.20–0.49), medium (0.50–0.79), or large (> 0.80) effect [13]. Despite this classification, some clinicians find SMD difficult to interpret in clinical practice. NNT was calculated using the approach introduced by Furukawa [21].

Furukawa’s method requires determination of a CER [22]. We used a cutoff for VAS pain of 3.4 or less (as described by Boonstra et al. [9] to represent mild musculoskeletal pain) to estimate the probability of a favorable event in the placebo group. We estimated the probability of a favorable event, the approximated CER, as the cumulative probability of VAS scores of patients to be below the cutoff of 3.4 assuming a normal distribution for VAS [16]. The CER was approximated by using the cumulative distribution function of the cutoff value using the pooled mean and SD of the VAS scores [6, 39]. For this purpose, we pooled data from four studies that used the same outcome scale and assessment methods and for which a data approximation was not needed [2, 3, 32, 51].

where Φ or CDF = probability of an event; μ = pooled mean; δ = pooled SD; and C = predetermined cutoff value.

Two-tailed alpha values of 0.05 or less along with nonoverlapping 95% CIs were considered statistically significant.

We also compared the effect of repeated injections of corticosteroids versus a single corticosteroid injection with a common comparator of a placebo injection. Three studies used repeated injections [44, 45, 47]. Richardson [47] administered two injections of prednisolone acetate, one at the first visit and the second 2 weeks later. Assessments occurred at the second and sixth weeks after initial injection. Neither assessment showed a significant difference. In two other studies, repeated injections were performed at the third and sixth weeks after the first injection [44, 45]. The mean pain score in the corticosteroid injection group was less than that of the placebo group only at the 6-week assessment (p = 0.0060) [44]. In the third study, there was a linear trend in decreasing mean VAS pain score from 5.8 to 2.7 after three injections. A similar trend was seen in the placebo group and because the time interaction is not shown, the pain reduction cannot be attributed solely to the corticosteroid injection [45].

To perform a multiple-treatments meta-analysis, we used subgroup analysis and then tested for subgroup differences [10].

Results

A corticosteroid injection did not reduce pain in adult patients with rotator cuff tendinosis more than a placebo injection during the third-month assessment. On average, adult patients with rotator cuff tendinosis receiving a corticosteroid injection experienced slight and transient pain relief more than a placebo injection at assessment times less than 2 months (Fig. 3). The pooled mean of the VAS pain in the control group was 5.2 (pooled SD, 0.5) before injection, 5.1 (pooled SD, 0.2) at the 1-month assessment, 3.9 (pooled SD, 1.2) at the 2-month assessment, and 3.8 (pooled SD, 1.4) at the 3-month assessment. We could not calculate an NNT at the 1-month assessment because the chance of having a VAS pain score less than 3.4 (our previously noted definition of mild pain [9]) was less than 1 in 1000 during this assessment time. In addition, the NNT was not calculated for assessment during the third month given that there is no difference between corticosteroid and placebo injections. The largest effect size for corticosteroid injections occurred at the assessment between 4 and 8 weeks with a Hedges’s g of 0.52 (0.27–0. 78) and NNT of 4.9 (3.3–9.5) (Table 2).

The pooled SMD of single and multiple corticosteroid injections was 0.44 in the first month assessment (p = 0.992). In the second month assessment, the pooled SMD of single corticosteroid injection was 0.51 whereas that of repeated injections was 0.54 (p = 0.918). In the third month assessment, the pooled SMD was 0.28 for single corticosteroid injection and 0.14 for repeated injections (p = 0.683) (Table 3).

Discussion

A corticosteroid injection into the subacromial space is a widely used palliative treatment for rotator cuff tendinosis. There are no known disease-modifying treatments. The ability of a corticosteroid injection to relieve symptoms ascribed to rotator cuff tendinosis is debated, with prior meta-analyses reaching different conclusions [15, 24, 27]. We performed a meta-analysis including several new prospective randomized controlled trials comparing corticosteroid and placebo injections [31, 37, 45], and using the Furukawa method [21] of calculating the NNT for a reduction in pain intensity to mild or less. We found no differences 3 months after injection. Patients in the corticosteroid injection group reported, on average, a small transient pain relief in comparison to patients receiving a placebo injection at assessment times less than 2 months. For every five patients treated with a corticosteroid injection, one will experience a slight, transient reduction of symptoms to mild pain. Pain did not improve with additional injections.

This review should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the severity of the tendinosis or duration of pain may have varied among studies (Table 1) [28, 41, 43]. Tendinosis can include a large spectrum of disorders and we have limited insight into practice patterns of the centers that produced each study. For example, some practices are more aggressive, with surgical intervention for patients with “high-grade partial tears,” whereas some practices may opt to treat these patients with injections. If these high-grade partial tears were included in some studies, and corticosteroid injections are not efficacious in addressing high-grade partial tears, it may skew the results of those studies negatively. Conversely, if patients with minimal symptoms or populations who are particularly prone to placebo response are included, this may skew results positively. Second, the studies enrolled patients with different prior or concurrent treatments. The results might be different for patients with more-selected indications, such as patients who are not satisfied with rotator cuff-strengthening exercises. It is possible that using corticosteroid injections as a second- or third-line treatment might decrease the NNT. However, it is also possible that the NNT would increase because this approach would remove patients predisposed to respond to any type of treatment (placebo responders). Third, the enrolled patients in the clinical trials seem to be younger than the patients with shoulder pain seen in a population-based study [49]. This may affect the generalizability of the findings. Fourth, pain relief in our study was measured based on the average VAS before and after intervention, and because we did not have the dataset of each clinical trial we could not calculate how many of these patients actually experienced a minimally clinical important difference (MCID) from their baseline pain. Despite that the MCID depends on the condition type, the severity, sex, and age, to our knowledge, the MCID of the VAS has not been studied for upper extremity problems. In musculoskeletal problems, however, the MCID has been shown to vary from 9 mm in low back pain to 37 mm in knee osteoarthritis [35]. Given that the MCID should be applied to changes in individual subjects, not to group changes, we were unable to determine how many of patients in the reviewed trials experienced a meaningful difference in their pain. In other words, although we found some transient pain relief after corticosteroid injections, these differences were small and in most or all cases, unlikely to be meaningful to patients [19]; however, we used a clinical threshold to define mild pain [9] and estimated the NNT of patients having no more than mild pain using the proportion of patients in the placebo and corticosteroid groups before injection and at each assessment time. This is particularly important because musculoskeletal pain tends to decline with time even without treatment and other approaches for NNT estimation do not take this into account [16]. Fifth, there was substantial heterogeneity in the studies that could not be explained by year of publication, type of placebo, quality assessment of studies, or repeated versus single injection. We used a random-effects model for meta-analysis, but this does not entirely account for the heterogeneity. Each reader can decide for him- or herself, but the positive results seen at short intervals (Fig. 3) seem to be driven by a small number of studies, with the study of Hong et al. [32] being a particular outlier. Although their study met our criteria for control of bias, if there were problems with their trial that cannot be detected from its publication, and we became aware of those problems and excluded it, we likely would see no benefit of corticosteroids. Sixth, we had to estimate the mean based on the figures and charts in some studies, the SD was not consistently reported, and we made calculations using some assumptions for some studies. However, two reviewers separately performed data synthesis to maximize reproducibility of the study. We used only four studies (ones with the same pain scale and sufficient data) [2, 3, 32, 51] to calculate the CER because the CER is crucial for NNT calculations. Seventh, despite that we did not limit our search to language or year of publication, there is a possibility of publication bias in the systematic review. This potentially could lead to overestimation of the results. However, further analysis showed it is unlikely that unpublished studies would change our results significantly. Eighth, we know little about the effect of a corticosteroid injection after 3 months because only four studies evaluated patients for more than 3 months. Ninth, the clinical trials were too small to provide information regarding safety. We know that corticosteroids are catabolic and likely to accelerate tendon degeneration [17]. Finally, there were insufficient data to conduct a meta-analysis for functional outcomes such as ROM or patient-reported outcome measures such as the DASH score.

We found that patients receiving corticosteroids had, on average, slight transient pain relief more than with placebo injection during first 2 months. This might be explained by our larger cohort compared with earlier meta-analyses, or by the inclusion of one new study with an exceptionally positive effect [32]. Numerous reviews have addressed the clinical effectiveness of corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain [7, 11, 15, 23–26, 35, 49, 54]. However, only a few studies pooled data [7, 11, 15, 24]. Coombes et al. [15] pooled the data from three studies and reported an unclear pain relief and shoulder function with corticosteroid injection. Gaujoux-Viala et al. [24] found a medium to large effect for corticosteroid injections for tendinopathy 2 months or less after injection. However, they used a mixed comparator in data pooling, and their injection sites included the elbow. Arroll and Goodyear-Smith [7] reported an NNT of 3.3 from pooled data of five studies addressing corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain in general. In their study, NNT was calculated by defining a “response” for the included trials using various outcomes and diverse definitions. An early Cochrane systematic review [11] pooled data at the fourth-week assessment from two studies with subacromial corticosteroid injection and found a small improvement in pain intensity and active ROM.

We found that additional corticosteroid injections did not result in lower pain intensity compared with one injection. The effect of a single corticosteroid injection versus multiple injections of corticosteroid for shoulder tendinosis has not been compared directly in a single trial, to our knowledge. In one trial [32], 20- or 40-mg triamcinolone acetonide injection yielded similar pain reduction and functional improvement at all assessments shorter than 2 months for the periarticular disorders of the shoulder. Similarly, higher doses of intraarticular corticosteroid did not significantly improve pain or functional outcome in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder [53]. In a trial of patients with elbow enthesopathy, an average of four corticosteroid injections had a poorer long-term pain reduction than a single injection [15]. In tendinopathies, neuropeptides, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and substance P are found to increase, so perhaps corticosteroid effects are mediated primarily by analgesic pathways [14, 20]. In light of this, there may be a threshold where the analgesic effects are outweighed by the deleterious effects of corticosteroids on the tendon tissue, which include collagen disorganization, decreased mechanical properties of tendon, and long-term harm to tendon tissue and cells [17]. The relationship of injection dosage to clinical benefit or harm is not well understood, and this uncertainty warrants further study. Until this is clarified, multiple steroid injections should be administered judiciously.

The appeal of corticosteroid injections for rotator cuff tendinopathy seems limited. From the patient’s perspective they are painful and only one in five will experience a transient decrease in their pain to mild or less. That is a very limited and short-term plan for a long-term problem, and the benefit may be illusory if the outlier studies were biased. Corticosteroids potentially could be harmful to the tendon. The resource utilization (office time, procedure charge, materials) seems difficult to justify. Many patients probably would not invest hope in this if they were paying for it themselves. As it stands they are widely used, probably to satisfy the desire for a “quick fix” or at least to take some action; to satisfy a passive and magical attitude toward health; out of habit or training; owing to inadequate accounting for the placebo effect; or for remuneration. The wide variation in treatment recommendations between physicians suggests that patients may not be getting complete, balanced, dispassionate information regarding their treatment options. A focus for future study would be the degree to which providing patients such information—perhaps in the form of a decision aid—might decrease the rate of corticosteroid injections and whether that would affect pain intensity and limitations in the short or long term. It is possible that the corticosteroid injection is hindering or delaying more-effective management strategies—effective coping strategies such as adaptation and resilience in particular—and that lower utilization of injections might improve outcomes.

References

Adebajo AO, Nash P, Hazleman BL. A prospective double blind dummy placebo controlled study comparing triamcinolone hexacetonide injection with oral diclofenac 50 mg TDS in patients with rotator cuff tendinitis. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1207–1210.

Akgun K, Birtane M, Akarirmak U. Is local subacromial corticosteroid injection beneficial in subacromial impingement syndrome? Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23:496–500.

Alvarez CM, Litchfield R, Jackowski D, Griffin S, Kirkley A. A prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing subacromial injection of betamethasone and xylocaine to xylocaine alone in chronic rotator cuff tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:255–262.

Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Bassol-Perea A, Rosado Pasos J. [Efficacy of the local injection of methylprednisolone acetate in the subacromial impingement syndrome: a randomized, double-blind trial] [in Spanish]. Reumatol Clin. 2008;4:49–54.

Andres BM, Murrell GA. Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1539–1554.

Anzures-Cabrera J, Sarpatwari A, Higgins JP. Expressing findings from meta-analyses of continuous outcomes in terms of risks. Stat Med. 2011;30:2967–2985.

Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulder: a meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:224–228.

Blair B, Rokito AS, Cuomo F, Jarolem K, Zuckerman JD. Efficacy of injections of corticosteroids for subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1685–1689.

Boonstra AM, Schiphorst Preuper HR, Balk GA, Stewart RE. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2014;155:2545–2550.

Borenstein M, Higgins JP. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev Sci. 2013;14:134–143.

Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004016.

Chard MD, Cawston TE, Riley GP, Gresham GA, Hazleman BL. Rotator cuff degeneration and lateral epicondylitis: a comparative histological study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:30–34.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159.

Coombes BK, Bisset L, Brooks P, Khan A, Vicenzino B. Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:461–469.

Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1751–1767.

da Costa BR, Rutjes AW, Johnston BC, Reichenbach S, Nuesch E, Tonia T, Gemperli A, Guyatt GH, Juni P. Methods to convert continuous outcomes into odds ratios of treatment response and numbers needed to treat: meta-epidemiological study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1445–1459.

Dean BJ, Lostis E, Oakley T, Rombach I, Morrey ME, Carr AJ. The risks and benefits of glucocorticoid treatment for tendinopathy: a systematic review of the effects of local glucocorticoid on tendon. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:570–576.

Dickersin K, Berlin JA. Meta-analysis: state-of-the-science. Epidemiol Rev. 1992;14:154–176.

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP, Peirce-Sandner S, Burke LB, Cowan P, Farrar JT, Hertz S, Raja SN, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Sampaio C. Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2009;146:238–244.

Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Chronic tendinopathy tissue pathology, pain mechanisms, and etiology with a special focus on inflammation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:3–15.

Furukawa TA. From effect size into number needed to treat. Lancet. 1999;353:1680.

Furukawa TA, Leucht S. How to obtain NNT from Cohen’s d: comparison of two methods. PloS One. 2011;6:e19070.

Garg N, Perry L, Deodhar A. Intra-articular and soft tissue injections, a systematic review of relative efficacy of various corticosteroids. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1695–1706.

Gaujoux-Viala C, Dougados M, Gossec L. Efficacy and safety of steroid injections for shoulder and elbow tendonitis: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1843–1849.

Goupille P, Sibilia J. Local corticosteroid injections in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinitis (except for frozen shoulder and calcific tendinitis). Groupe Rhumatologique Francais de l’Epaule (GREP). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:561–566.

Green S, Buchbinder R, Glazier R, Forbes A. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions for painful shoulder: selection criteria, outcome assessment, and efficacy. BMJ. 1998;316:354–360.

Hart L. Corticosteroid and other injections in the management of tendinopathies: a review. Clin J Sport Med. 2011; 21:540–541.

Hawkins RJ, Kennedy JC. Impingement syndrome in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1980; 8:151–158.

Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass’ estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat. 1981;6:107–128.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560.

Holt TA, Mant D, Carr A, Gwilym S, Beard D, Toms C, Yu LM, Rees J. Corticosteroid injection for shoulder pain: single-blind randomized pilot trial in primary care. Trials. 2013;14:425.

Hong JY, Yoon SH, Moon do J, Kwack KS, Joen B, Lee HY. Comparison of high- and low-dose corticosteroid in subacromial injection for periarticular shoulder disorder: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1951–1960.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12.

Johnston BC, Alonso-Coello P, Friedrich JO, Mustafa RA, Tikkinen KA, Neumann I, Vandvik PO, Akl EA, da Costa BR, Adhikari NK, Dalmau GM, Kosunen E, Mustonen J, Crawford MW, Thabane L, Guyatt GH. Do clinicians understand the size of treatment effects? A randomized survey across 8 countries. CMAJ. 2016;188:25–32.

Katz NP, Paillard FC, Ekman E. Determining the clinical importance of treatment benefits for interventions for painful orthopedic conditions. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:24.

Koester MC, Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Spindler KP. The efficacy of subacromial corticosteroid injection in the treatment of rotator cuff disease: a systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:3–11.

Lin YH, Chiou HJ, Wang HK, Lai YC, Chou YH, Chang CY. Comparison of the analgesic effect of xylocaine only with xylocaine and corticosteroid injection after ultrasonographically-guided percutaneous treatment for rotator cuff calcific tendonosis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:127–132.

McInerney JJ, Dias J, Durham S, Evans A. Randomised controlled trial of single, subacromial injection of methylprednisolone in patients with persistent, post-traumatic impingment of the shoulder. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:218–221.

Meister R, von Wolff A, Kriston L. Odds ratios of treatment response were well approximated from continuous rating scale scores for meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:740–751.

Mohamadi A, Chan J, Ring D. Effect of corticosteroid injection in comparison with placebo for adult patients rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta analysis. PROSPERO 2015:CRD42015025964 Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015025964. Accessed July 19, 2016.

Neer CS 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173: 70–77.

Orwin R.G. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 1983; 8:157–159.

Palmer K, Walker-Bone K, Linaker C, Reading I, Kellingray S, Coggon D, Cooper C. The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:5–11.

Penning LI, de Bie RA, Walenkamp GH. The effectiveness of injections of hyaluronic acid or corticosteroid in patients with subacromial impingement: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1246–1252.

Penning LI, de Bie RA, Walenkamp GH. Subacromial triamcinolone acetonide, hyaluronic acid and saline injections for shoulder pain an RCT investigating the effectiveness in the first days. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:352.

Petri M, Dobrow R, Neiman R, Whiting-O’Keefe Q, Seaman WE. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the treatment of the painful shoulder. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1040–1045.

Richardson AT. Ernest Fletcher Lecture. The painful shoulder. Proc R Soc Med. 1975;68:731–736.

Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull, 1979; 86: 638–641.

Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, Brammah T, Busby H, Roxby M, Simmons A, Williams G. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:649-655.

van der Heijden GJ, van der Windt DA, Kleijnen J, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Steroid injections for shoulder disorders: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:309–316.

Vecchio PC, Hazleman BL, King RH. A double-blind trial comparing subacromial methylprednisolone and lignocaine in acute rotator cuff tendinitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:743–745.

Withrington RH, Girgis FL, Seifert MH. A placebo-controlled trial of steroid injections in the treatment of supraspinatus tendonitis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1985;14:76–78.

Yoon SH, Lee HY, Lee HJ, Kwack KS. Optimal dose of intra-articular corticosteroids for adhesive capsulitis: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1133–1139.

Zheng XQ, Li K, Wei YD, Tie HT, Yi XY, Huang W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroid for treatment of shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1824–1831.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Bramer BSc (medical librarian, Erasmus Medical Center, The Netherlands), for assistance in performing the literature search. We also thank Amir Reza Kachooei MD (Department of Orthopaedics, Hand and Upper Extremity Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) for assistance with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis statistical software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

The protocol of the study is registered and accessible at the international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42015025964).

This work was performed at Massachusetts General Hospital–Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamadi, A., Chan, J.J., Claessen, F.M.A.P. et al. Corticosteroid Injections Give Small and Transient Pain Relief in Rotator Cuff Tendinosis: A Meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475, 232–243 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5002-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5002-1