Abstract

Background

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) continues to be one of the most successful surgical procedures in the medical field. However, over the last two decades, the use of modularity and alternative bearings in THA has become routine. Given the known problems associated with hard-on-hard bearing couples, including taper failures with more modular stem designs, local and systemic effects from metal-on-metal bearings, and fractures with ceramic-on-ceramic bearings, it is not known whether in aggregate the survivorship of these implants is better or worse than the metal-on-polyethylene bearings that they sought to replace.

Questions/purposes

Have alternative bearings (metal-on-metal and ceramic-on-ceramic) and implant modularity decreased revision rates of primary THAs?

Methods

In this systematic review of MEDLINE and EMBASE, we used several Boolean search strings for each topic and surveyed national registry data from English-speaking countries. Clinical research (Level IV or higher) with ≥ 5 years of followup was included; retrieval studies and case reports were excluded. We included registry data at ≥ 7 years followup. A total of 32 studies (and five registry reports) on metal-on-metal, 19 studies (and five registry reports) on ceramic-on-ceramic, and 20 studies (and one registry report) on modular stem designs met inclusion criteria and were evaluated in detail. Insufficient data were available on metal-on-ceramic and ceramic-on-metal implants, and monoblock acetabular designs were evaluated in another recent systematic review so these were not evaluated here.

Results

There was no evidence in the literature that alternative bearings (either metal-on-metal or ceramic-on-ceramic) in THA have decreased revision rates. Registry data, however, showed that large head metal-on-metal implants have lower 7- to 10-year survivorship than do standard bearings. In THA, modular exchangeable femoral neck implants had a lower 10-year survival rate in both literature reviews and in registry data compared with combined registry primary THA implant survivorship.

Conclusions

Despite improvements in implant technology, there is no evidence that alternative bearings or modularity have resulted in decreased THA revision rates after 5 years. In fact, both large head metal-on-metal THA and added modularity may well lower survivorship and should only be used in select cases in which the mission cannot be achieved without it. Based on this experience, followup and/or postmarket surveillance studies should have a duration of at least 5 years before introducing new alternative bearings or modularity on a widespread scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the increased activity demands of patients and a younger age at the time of the primary procedure have sparked the development of alternative bearing surfaces in hip arthroplasty (here defined as bearings that replaced the polyethylene counterface) with the goal of addressing lower reported survivorships in younger, more active patient populations [10, 21, 33, 34, 38, 40, 41]. However, some metal-on-metal (MoM) THA designs have been associated with premature revisions related to acute local reactions and high systemic metal ion levels, and reports of ceramic component breakage and squeaking have raised questions about the cost-benefit balance with those implants as well [10, 16, 32, 33, 36, 38, 50, 52, 60, 66, 69, 77].

The use of modular components for THA, available since the late 1970s, has become increasingly popular and has expanded into modular exchangeable femoral necks and proximal implant bodies. These implants seek to improve the fit of the implant to each patient’s specific anatomy in hopes of recreating the anatomical center of the hip in all three planes with the goal of improving implant performance and longevity [1, 6, 17, 24, 27, 35]. These implants also seek to allow surgeons to have more options for easier reconstruction of patients with complex deformities and difficult revisions that involve bone loss and/or deformity. These marketed advantages have, however, come with increased risks and complications [4, 15, 27, 44, 70]. Unfortunately, adding another metal taper junction may increase the burden of corrosion debris and the risk of local tissue reactions as well as serve as a possible weak link that can increase the risk of a catastrophic failure [4, 15, 27, 44, 70]. As with any additional technological advancement in implant designs, both alternative bearings and increased modularity add cost to the implants in most cases. It is important to understand whether these cost increases are associated with any results that might affirm the benefit of their use within primary THA.

To determine if alternative bearings or femoral component modularity (using another implant connection other than the head-neck taper connection) have decreased the revision rates after at least 5 years, we undertook a systematic review of clinical research reports and of the national joint registries.

Search Strategy and Criteria

A systematic literature search was done in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. “Survivorship” was used as the primary search parameter. Only therapeutic studies published in English, Level IV or better, with at least 5 years of followup were included. Case reports, retrieval studies, animal/basic science studies, and in vitro studies, including those on bearing wear, were excluded. Articles reporting on THA revision, hip resurfacing, and corrosion in modular components also were excluded. The search parameters and Boolean strings were modified multiple times to increase the likelihood that all relevant publications were identified. All bibliographies were searched by hand to determine if other studies that might not have been revealed in the search parameters were available for inclusion. Bibliographies from all qualified citations were queried for additional articles that met inclusion criteria. If any other systematic reviews were found for any search, the timeline for citations to be reviewed was started from this point forward.

Country registry reports were also reviewed for comparison of modular THA revision rates and survivorship if implant types were identified. We included registry data at ≥ 7 years of followup. The registry reports reviewed were those of England and Wales, Norway, Sweden, Denmark (if an English version was available), Australia, and New Zealand [1, 56, 59, 62, 76]. The Kaiser Permanente publication database also was reviewed for relevant publications.

Insufficient data were available on alternative polymers (eg, polyetheretherketone [PEEK]), metal-on-ceramic and ceramic-on-metal implants, and monoblock acetabular designs, which were evaluated in other recent systematic reviews [31, 83], so these were not evaluated here. Study quality was specified by listing the level of evidence for each of the studies included in the systematic review.

Alternative Bearing Search Criteria

The search was performed using a Boolean string containing the following search terms: hip, prosthesis (arthroplasty, replacement), survival (survivorship, longevity, endurance, durability, performance), joint (bearing, articulation), and alternative (metal-on-metal, metal/metal, all-metal, all-ceramic, ceramic-on-ceramic, ceramic/ceramic, ceramic/metal, polyetheretherketone, PEEK, carbon fiber). The principal search terms were connected with “AND”, whereas the terms in parentheses were used interchangeably with the principal term and connected with “OR”. The search was confined to clinical trial articles published from January 1998 through October 2013, resulting in a total of 776 articles. All of the abstracts for these articles were reviewed and 148 were identified as duplicates between MEDLINE and EMBASE. The remaining 628 abstracts were then filtered according to the inclusion criteria described previously, leading to the elimination of 577 and leaving 51 articles for review. Of these, 32 papers reported on MoM THA and 19 on ceramic-on-ceramic THA. Most of the included articles were of Level IV evidence. In the MoM group, there were only two reports with Level I to II evidence [86, 87] and one report with Level III evidence [18]. In the ceramic-on-ceramic group, there were two reports with Level I evidence [16, 53], one report with Level II evidence [50], and two reports with Level III evidence [19, 69] (Tables 1 and 2).

Modularity Search Criteria

For THA, modularity of the femoral stem was defined as a design that included a second modular junction outside the head-neck taper connection. All combinations of the following terms were searched: hip, arthroplasty (or replacement), modular (resulting in 746 citations when “arthroplasty” was used and 635 when “replacement” was used in the search string) as well as taper (64 citations) and monoblock (29 citations). No study involving retrieval analysis or metal ion levels was included. Twenty reports on dual modular femoral components in the literature met inclusion criteria [4, 6, 8, 12, 17, 19, 20, 24, 35, 40, 44, 48, 68, 71, 73, 75, 78–81]. The levels of evidence for these articles that met inclusion criteria were: Level I (zero), Level II (four), Level III (four), and Level IV (twelve).

For exclusion criteria, no metal ion or retrieval studies or case reports were included. Dual mobility acetabular components were not included in the analysis because their second articulating junction may increase wear but are associated with other complications not specific to fixed-bearing acetabular components. After applying these search parameters and inclusion/exclusion criteria, we ended up with 20 publications and one registry report.

Results

Alternative Bearings: Metal-on-metal

For all combined THA types of implants, cumulative revision rate at 10 years listed in the Australian registry had a 95% confidence interval that ranged from 2% to 14% for femoral stems, from 3% to 100% for acetabular components, and from 2% to 10% for combinations with an overall THA revision rate of 6%. Values for the overall THA revision at 10 years ranged from 4% to 6% for all registries reviewed [1, 56, 59, 62, 76]. These combined results are used for comparison of the alternative bearing and modularity data subsequently.

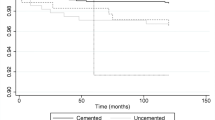

The reported survival rates at 5 years ranged from 92.4% to 100%, whereas the 10-year survival rates ranged from 82% to 100% (Table 1). Because all but one [86, 87] of the studies were retrospective (Table 1), no meta-analysis or any other type of statistical analysis that pooled the data was performed, and therefore no trends could be established. In the only reported randomized controlled trial [86, 87], cemented Stanmore 28 mm MoM THAs (Biomet Inc, Warsaw, IN, USA) were not found to be superior to their metal-on-polyethylene counterparts with 10-year survival rates of 95.5% (Table 1) and 96.8%, respectively (p = 0.402) [87].

By contrast, the Australian registry documented a cumulative MoM revision rate of 9.6% (lower and upper boundary of 95% confidence interval [CI], 9.2%–10.1%) at 5 years and 15.5% (14.8–16.3) at 10 years for prostheses with fixed femoral necks [1]. This was the highest rate of revision of all investigated bearing types in the registry. Such data are mirrored in the UK registry, in which MoM performed much worse than any other bearing type [56]. Revision rates of uncemented MoM THAs were reported as high as 7.7% (7.3–8.0) at 5 years and 17.7% (15.9–19.6) at 9 years and were only marginally better with hybrid fixation [56]. The New Zealand registry differs in that it reported unsatisfactory results for only 36-mm diameter bearings and larger [59]. Thus, for uncemented cups with a liner having a small bearing diameter (≤ 28 mm), MoM couples had lower revision rates per 100 component years than ceramic-on-ceramic, ceramic-on-polyethylene, and metal-on-polyethylene couples (p ≤ 0.05). The influence of MoM head size on revision rate has also been documented in a recent supplementary report of the Australian registry, where head sizes of ≤ 28 mm produced smaller cumulative revision rates of 3.7% (3.1%–4.5%) and 5.7% (4.8%–6.6%) at 5 and 10 years, respectively [2]. These revision rates are better than those for conventional polyethylene bearings (7.7% [7.2%–8.3%] at 10 years) but slightly worse than those paired with crosslinked polyethylene (4.5% [4.3%–4.8%] at 10 years).

Alternative Bearings: Ceramic-on-ceramic

The reported survival rates at 5 years ranged from 98.3% [37] to 100% [45] and at 10 years from 83.9% [7] to 100% [45] (Table 2). Of the three prospective comparative studies (Level I or II) that were retrieved, one found the ceramic-on-ceramic (CoC) and control hard-on-polyethylene THA had comparable survivorship, whereas two found the CoC had greater survivorship. Thus, Lombardi et al. [50] determined a survivorship at 6 years of 95% for CoC bearing versus 93% for the ceramic-on-polyethylene bearing (p = 0.44). The CoC bearing couple entailed a Biolox Delta head articulating against a Biolox Forte cup (CeramTec GmbH, Plochingen, Germany), whereas the control couples consisted of a zirconia head articulating against a highly crosslinked polyethylene liner (ArCom; Biomet Inc, Warsaw, IN, USA). On the other hand, Mesko et al. [53] recorded survival rates at 10 years of 96.8% for the alumina-alumina bearing THA (ABC and Trident; Stryker Orthopaedic, Mahwah, NJ, USA) versus 92.1% for the control CoCrMo-polyethylene, which were significantly different (p = 0.0017). D’Antonio et al. [16] found survivorships at 10 years of 97.9% and 95.2% for two alumina-on-alumina THAs (“System I” and “System II”) versus 91.3% for the control conventional polyethylene (gamma-sterilized in an inert atmosphere) articulating against a CoCrMo head (“System III”). The difference among the three systems was significantly different (p = 0.027, no pairwise comparison of the groups was provided). The authors determined that the risk of revision relative to the metal-on-polyethylene control THA was 0.183 for System I and 0.394 for System II [16].

Based on the registry data, CoC bearings performed as well as or better than conventional polyethylene-on-metal and as well as highly crosslinked polyethylene against metal or ceramics. For prostheses with a fixed femoral neck, the Australian registry documented a cumulative revision rate of 2.9% (2.8%–3.1%) and 4.8% (4.5%–5.2%) at 5 and 10 years, respectively [1]. This is similar to a bearing with crosslinked polyethylene (4.5% [4.3%–4.8%] when paired with metal and 5.1% [4.5%–5.8%] when paired with ceramic at 10 years). The UK registry [56] documents low revision rates for CoC, which in the case of hybrid fixation (2.3% [1.8%–3.0%] at 9 years) rival those of the front runner: all cemented/ceramic versus polyethylene (1.8% [1.5%–2.2%] at 9 years). The New Zealand registry [59] also reported overall low revision rates for CoC, except for head sizes ≤ 28 mm, in which the CoC articulation showed significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher revision rates when compared with bearing types with polyethylene.

Modular Femoral Components in THA

In the literature, the survivorship for exchangeable modular necks was similar to overall reported survivorship from registry data but one registry reported a higher revision rate for all exchangeable modular femoral neck prostheses [1]. This increased frequency of revision with exchangeable neck prostheses occurred with all bearing surfaces in the Australian Registry (Table 3). Twelve studies reported on various types of modular femoral neck and stem components with a range of survivorship from 91% to 100% with a range of followup of 8.6 and 5 years, respectively [4, 8, 17, 19, 20, 35, 44, 68, 73, 79–81]. Eight reports dealing specifically with the S-ROM modular stem/body (DePuy Orthopaedics Inc, Warsaw, IN, USA) reported a range of survivorships for aseptic loosening of 93.3% to 100% with a range of followup of 19 years and 10 years, respectively [6, 12, 24, 40, 48, 71, 75, 78]. One report for an SROM type of stem reported an 84% survivorship when revision for any reason was considered at an average of 17 years [48].

The Australian registry compared 6659 THAs performed with femoral stems with exchangeable necks with 166,932 THAs performed with fixed-neck stems and found a cumulative percent revision at 7 years of 8.9% (95% CI, 7.9%–10.1%) for exchangeable neck prostheses compared with 4.2% (95% CI, 4.1%–4.3%) for fixed stems [1].

Discussion

Every year, healthcare costs are increasing in the United States and, therefore, a critical evaluation of their impact on patient care should be routine. Although THA continues to be one of the most successful operations in orthopaedic surgery, we continue to introduce new technologies with the aim to further improve survivorship and implant performance, especially in younger patients, who are having the procedure in increasing numbers. In general, the use of both modularity and alternative bearings increases implant costs. With questions being raised concerning corrosion of modular taper junctions and use of some hard-on-hard bearings increasing the risk of complications, we sought to answer the question of whether either of these implant design features has produced improvements in the survivorship or risk of revision at 5 years or longer after the index procedure [9, 10, 15, 16, 22, 25, 27, 32, 33, 36, 42, 46, 50, 52, 60, 69, 77]. In general, both alternative bearings and modularity showed no evidence of improvements in survivorship in either the literature or registry reports.

This study had a number of limitations. First, the study quality was low but this was strengthened by including registry data where available. It must be realized that many other variables are considered within registry data and within the literature reports that were reviewed. The reporting within many retrospective studies does not take into account patient demographics and risk factors or surgical technique. The literature reviewed also mixes multiple design variables, especially when modularity issues are compared (femoral neck modular connections may be of a different metallic alloy as well as different designs). There also have been unanticipated adverse events that have occurred both with alternative bearings and implants using increased modularity; these were not evaluated in this review, because sufficient detail about reasons for revision often is not provided in published reports nor included in registry data.

The systematic review concerning alternative bearings revealed that small head MoM had similar but large head MoM had inferior results compared with both standard and highly crosslinked polyethylene mated with any hard material. This evidence is solely based on registry data, because there are insufficient data to make such comparisons fairly in the nonregistry study populations. MoM revision rates at 10 years ranged from 0% to 12% in the clinical series studies that we surveyed, whereas in the registries, they ranged from 5.7% (Australian registry [1], small MoM heads) to 17.7% (National Joint Registry of England [56]; aggregate for uncemented prostheses). The fact that we found only one randomized controlled trial that compared MoM with metal-on-polyethylene barred us from performing a meta-analysis between both bearing types. For reference, in a meta-analysis by Clement et al. [14], revision rates for conventional polyethylene bearings ranged from 8% to 18%. The dearth of long-term clinical trials in the literature points to the power of registry data. Because the United States accounts for such a large percentage of the THAs performed, a proper registry with annual reports may have alerted surgeons to the higher revision rates earlier in the case of large head MoM instead of relying on reports from experts and tertiary care centers that reported no differences in survivorship.

In our analysis, CoC had better results than MoM. Our review also found that CoC bearings in general were found to perform better than conventional polyethylene-on-metal but not as well as metal on highly crosslinked polyethylene at 10 years. The benefits of these bearings may be justified but according to the survivorship review we made in this report, its cost may not be justified; this would need to be the focus of future studies, because we did not specifically evaluate costs here.

According to all registry reports, THA modular necks had lower survivorship as did the clinical series that we reviewed for this aspect of modularity [1, 4, 6, 8, 12, 17, 19, 20, 24, 35, 40, 44, 48, 68, 71, 73, 75, 78–81]. Similar survivorships and revision rates were found for modular stem/body and body/neck femoral components, whereas registry data revealed similar results except when these types of stems were paired with a MoM articulating bearing, which was reported to increase revision rates even further [1]. This further begs the question whether a modular taper in a femoral stem that is added along the axis of the diaphysis (ie, a solid stem with a modular body or a solid stem neck with a modular body) creates less fretting and local tissue reactions than a second modular taper added to the neck (ie, exchangeable modular femoral neck implants) resulting from the loading conditions and added bony stability afforded to the modular connection.

In summary, increased modularity of the femoral component appears to have not improved implant revision rates. Registry data show an increase in revision rate for exchangeable femoral neck modular stems. Whether this is the result of implant taper mismatch in the assembly of the added taper junction, implant material or design, or surgical technical errors remains to be established. Based on the experiences reported in this review, there should be a 5-year followup and/or postmarket surveillance studies of at least 5 years before introducing new alternative bearings or modularity in THA on a widespread scale. Surgeons need to consider all aspects of alternative bearings and modularity before using them on a widespread fashion within their practice.

References

Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2013. Available at: https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/annual-reports-2013. Accessed June 25, 2014.

Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Supplementary Report: Metal on Metal Total Conventional Hip Arthroplasty, 2013. Available at: https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/annual-reports-2013. Accessed June 25, 2014.

Beldame J, Carreras F, Oger P, Beaufils P. Cementless cups do not increase osteolysis risk in metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Apropos of 106 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:478–490.

Benazzo F, Rossi SM, Cecconi D, Piovani L, Ravasi F. Mid-term results of an uncemented femoral stem with modular neck options. Hip Int. 2010;20:427–433.

Bernstein M, Desy NM, Petit A, Zukor DJ, Huk OL, Antoniou J. Long-term follow up and metal ion trend of patients with metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2012;36:1807–1812.

Biant LC, Bruce WJ, Assini JB, Walker PM, Walsh WR. The anatomically difficult primary total hip replacement: medium- to long-term results using a cementless modular stem. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:430–435.

Bizot P, Banallec L, Sedel L, Nizard R. Alumina-on-alumina total hip prostheses in patients 40 years of age or younger. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;379:68–76.

Blakey CM, Eswaramoorthy VK, Hamilton LC, Biant LC, Field RE. Mid-term results of the modular ANCA-Fit femoral component in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1561–1565.

Bolland BJ, Culliford DJ, Langton DJ, Millington JP, Arden NK, Latham JM. High failure rates with a large-diameter hybrid metal-on-metal total hip replacement: clinical, radiological and retrieval analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:608–615.

Boyer P, Huten D, Loriaut P, Lestrat V, Jeanrot C, Massin P. Is alumina-on-alumina ceramic bearings total hip replacement the right choice in patients younger than 50 years of age? A 7- to 15-year follow-up study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:616–622.

Brown SR, Davies WA, DeHeer DH, Swanson AB. Long-term survival of McKee-Farrar total hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;402:157–163.

Cameron HU, Keppler L, McTighe T. The role of modularity in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(Suppl 1):89–92.

Chang JS, Han DJ, Park SK, Sung JH, Ha YC. Cementless total hip arthroplasty in patients with osteonecrosis after kidney transplantation. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:824–827.

Clement ND, Biant LC, Breusch SJ. Total hip arthroplasty: to cement or not to cement the acetabular socket? A critical review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:411–427.

Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck-body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:865–872.

D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. Ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty have high survivorship at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:373–381.

Dagnino A, Grappiolo G, Benazzo FM, Learmonth ID, Spotorno L, Portinaro N. Medium-term outcome in patients treated with total hip arthroplasty using a modular femoral stem. Hip Int. 2012;22:274–279.

Dastane MR, Long WT, Wan Z, Chao L, Dorr LD. Metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty does equally well in osteonecrosis and osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1148–1153.

Daurka JS, Malik AK, Robin DA, Witt JD. The results of uncemented total hip replacement in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis at ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1618–1624.

De la Torre BJ, Chaparro M, Romanillos JO, Zarzoso S, Mosquera M, Rodriguez G. 10 years results of an uncemented metaphyseal fit modular stem in elderly patients. Indian J Orthop. 2011;45:351–358.

Delaunay CP, Bonnomet F, Clavert P, Laffargue P, Migaud H. THA using metal-on-metal articulation in active patients younger than 50 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:340–346.

Descamps S, Bouillet B, Boisgard S, Levai JP. High incidence of loosening at 5-year follow-up of a cemented metal-on-metal acetabular component in THR. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2009;19:559–563.

Dorr LD, Wan Z, Longjohn DB, Dubois B, Murken R. Total hip arthroplasty with use of the Metasul metal-on-metal articulation. Four to seven-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:789–798.

Drexler M, Dwyer T, Marmor M, Abolghasemian M, Chakravertty R, Chechik O, Cameron HU. Nineteen-year results of THA using modular 9 mm S-ROM femoral component in patients with small femoral canals. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1667–1670.

Engh CA Jr, Ho H, Engh CA, Hamilton WG, Fricka KB. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty adverse local tissue reaction. Semin Arthroplasty. 2010;21:19–23.

Eswaramoorthy V, Moonot P, Kalairajah Y, Biant LC, Field RE. The Metasul metal-on-metal articulation in primary total hip replacement: clinical and radiological results at ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1278–1283.

Gill IP, Webb J, Sloan K, Beaver RJ. Corrosion at the neck-stem junction as a cause of metal ion release and pseudotumour formation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:895–900.

Girard J, Bocquet D, Autissier G, Fouilleron N, Fron D, Migaud H. Metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in patients thirty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2419–2426.

Girard J, Combes A, Herent S, Migaud H. Metal-on-metal cups cemented into reinforcement rings: a possible new acetabular reconstruction procedure for young and active patients. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:103–109.

Grübl A, Marker M, Brodner W, Giurea A, Heinze G, Meisinger V, Zehetgruber H, Kotz R. Long-term follow-up of metal-on-metal total hip replacement. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:841–848.

Halma JJ, Vogely HC, Dhert WJ, Van Gaalen SM, de Gast A. Do monoblock cups improve survivorship, decrease wear, or reduce osteolysis in uncemented total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3572–3580.

Hasegawa M, Sudo A, Uchida A. Alumina ceramic-on-ceramic total hip replacement with a layered acetabular component. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:877–882.

Hsu JE, Kinsella SD, Garino JP, Lee GC. Ten-year follow-up of patients younger than 50 years with modern ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 2011;22:229–233.

Hwang KT, Kim YH, Kim YS, Choi IY. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with a metal-on-metal bearing in patients younger than 50 years. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:1481–1487.

Ito H, Matsuno T, Aok Y, Minami A. Total hip arthroplasty using an Omniflex modular system: 5 to 12 years followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:98–106.

Jack CM, Molloy DO, Walter WL, Zicat BA, Walter WK. The use of ceramic-on-ceramic bearings in isolated revision of the acetabular component. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:333–338.

Jameson SS, Mason JM, Baker PN, Jettoo P, Deehan DJ, Reed MR. Factors influencing revision risk following 15,740 single-brand hybrid hip arthroplasties: a cohort study from a National Joint Registry. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1152–1159.

Kamath AF, Prieto H, Lewallen DG. Alternative bearings in total hip arthroplasty in the young patient. Orthop Clin North Am. 2013;44:451–462.

Kawano S, Sonohata M, Shimazaki T, Kitajima M, Mawatari M, Hotokebuchi T. Failure analysis of alumina on alumina total hip arthroplasty with a layered acetabular component: minimum ten-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1822–1827.

Kim SM, Lim SJ, Moon YW, Kim YT, Ko KR, Park YS. Cementless modular total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than fifty with femoral head osteonecrosis: minimum fifteen-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:504–509.

Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with ceramic-on-ceramic bearing in patients younger than 45 years with femoral-head osteonecrosis. Int Orthop. 2010;34:1123–1127.

Kindsfater KA, SychterzTerefenko CJ, Gruen TA, Sherman CM. Minimum 5-year results of modular metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:545–550.

Korovessis P, Petsinis G, Repanti M, Repantis T. Metallosis after contemporary metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Five to nine-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1183–1191.

Krishnan H, Krishnan SP, Blunn G, Skinner JA, Hart AJ. Modular neck femoral stems. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:1011–1021.

Kusaba A, Sunami H, Kondo S, Kuroki Y. Uncemented ceramic-on-ceramic bearing couple for dysplastic osteoarthritis: a 5- to 11-year follow-up study. Semin Arthroplasty. 2011;22:240–247.

Langton DJ, Joyce TJ, Jameson SS, Lord J, Van Orsouw M, Holland JP, Nargol AV, DeSmet KA. Adverse reaction to metal debris following hip resurfacing: the influence of component type, orientation and volumetric wear. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:164–171.

Lazennec JY, Boyer P, Poupon J, Rousseau MA, Roy C, Ravaud P, Catonné Y. Outcome and serum ion determination up to 11 years after implantation of a cemented metal-on-metal hip prosthesis. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:168–173.

Le D, Smith K, Tanzer D, Tanzer M. Modular femoral sleeve and stem implant provides long-term total hip survivorship. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:508–513.

Liudahl AA, Liu SS, Goetz DD, Mahoney CR, Callaghan JJ. Metal on metal total hip arthroplasty using modular acetabular shells. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:867–871.

Lombardi AV Jr, Berend KR, Seng BE, Clarke IC, Adams JB. Delta ceramic-on-alumina ceramic articulation in primary THA: prospective, randomized FDA-IDE study and retrieval analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:367–374.

Long WT, Dorr LD, Gendelman V. An American experience with metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties: a 7-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(Suppl 3):29–34.

Malem D, Nagy MT, Ghosh S, Shah B. Catastrophic failure of ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty presenting as squeaking hip. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii: bcr-2013-008614. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008614.

Mesko JW, D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Bierbaum BE, Naughton M. Ceramic-on-ceramic hip outcome at a 5- to 10-year interval: has it lived up to its expectations? J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:172–177.

Migaud H, Jobin A, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Laffargue P, Duquennoy A. Cementless metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in patients less than 50 years of age: comparison with a matched control group using ceramic-on-polyethylene after a minimum 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(Suppl 3):23–28.

Milosev I, Trebse R, Kovac S, Cör A, Pisot V. Survivorship and retrieval analysis of Sikomet metal-on-metal total hip replacements at a mean of seven years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1173–1182.

National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland 10th Annual Report 2013. Available at: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Reports,PublicationsandMinutes/Annualreports/tabid/86/Default.aspx. Accessed June 24, 2014.

Neuerburg C, Impellizzeri F, Goldhahn J, Frey P, Naal FD, von Knoch M, Leunig M, von Knoch F. Survivorship of second-generation metal-on-metal primary total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:527–353.

Neumann DR, Thaler C, Hitzl W, Huber M, Hofstädter T, Dorn U. Long-term results of a contemporary metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a 10-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:700–708.

New Zealand Joint Registry Fourteen year report 1999 to 2012. Available at: http://www.nzoa.org.nz/nz-joint-registry. Accessed June 25, 2014.

Nikolaou VS, Edwards MR, Bogoch E, Schemitsch EH, Waddell JP. A prospective randomised controlled trial comparing three alternative bearing surfaces in primary total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:459–465.

Nikolaou VS, Petit A, Debiparshad K, Huk OL, Zukor DJ, Antoniou J. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty–five- to 11-year follow-up. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(Suppl 1):S77–83.

Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 2010 Publication, ISBN: 978-82-91847-15-3. Available at: http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/#Publications. Accessed June 25, 2014.

Petsatodis GE, Papadopoulos PP, Papavasiliou KA, Hatzokos IG, Agathangelidis FG, Christodoulou AG. Primary cementless total hip arthroplasty with an alumina ceramic-on-ceramic bearing: results after a minimum of twenty years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:639–644.

Randelli F, Banci L, D’Anna A, Visentin O, Randelli G. Cementless Metasul metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties at 13 years. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:186–192.

Reito A, Eskelinen A, Puolakka T, Pajamäki J. Results of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing in patients 40 years old and younger. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133:267–273.

Repantis T, Vitsas V, Korovessis P. Poor mid-term survival of the low-carbide metal-on-metal Zweymüller-plus total hip arthroplasty system: a concise follow-up, at a minimum of ten years, of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:e331–334.

Saito S, Ryu J, Watanabe M, Ishii T, Saigo K. Midterm results of Metasul metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:1105–1110.

Sakai T, Ohzono K, Nishii T, Miki H, Takao M, Sugano N. A modular femoral neck and head system works well in cementless total hip replacement for patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:770–776.

Seyler TM, Bonutti PM, Shen J, Naughton M, Kester M. Use of an alumina-on-alumina bearing system in total hip arthroplasty for osteonecrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 3):116–125.

Shiga T, Mori M, Hayashida T, Fujiwara Y, Ogura T. Disassembly of a modular femoral component after femoral head prosthetic replacement. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:659.e17–19.

Sporer SM, Obar RJ, Bernini PM. Primary total hip arthroplasty using a modular proximally coated prosthesis in patients older than 70: two to eight year results. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:197–203.

Steppacher SD, Ecker TM, Tannast M, Murphy SB. Absence of osteolysis in uncemented alumina ceramic-on-ceramic THA in patients younger than 50 years after two to 14 years. Semin Arthroplasty. 2011;22:248–253.

Suehara H, Fujioka M, Inoue S, Takahashi K, Ueshima K, Kubo T. Clinical and radiographic results for the Richards Modular Hip System prosthesis in total hip arthroplasty: average 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:369–374.

Sugano N, Takao M, Sakai T, Nishii T, Miki H, Ohzono K. Eleven- to 14-year follow-up results of cementless total hip arthroplasty using a third-generation alumina ceramic-on-ceramic bearing. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:736–741.

Suzuki K, Kawachi S, Matsubara M, Morita S, Jinno T, Shinomiya K. Cementless total hip replacement after previous intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy for advanced osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1155–1157.

Swedish Hip Register Report 2010. Available at: http://www.shpr.se/en/Publications/DocumentsReports.aspx. Accessed June 25, 2014.

Synder M, Drobniewski M, Sibiński M. Long-term results of cementless hip arthroplasty with ceramic-on-ceramic articulation. Int Orthop. 2012;36:2225–2229.

Takao M, Ohzono K, Nishii T, Miki H, Nakamura N, Sugano N. Cementless modular total hip arthroplasty with subtrochanteric shortening osteotomy for hips with developmental dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:548–555.

Traina F, De Fine M, Abati CN, Bordini B, Toni A. Outcomes of total hip replacement in patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1133–1139.

Traina F, De Fine M, Biondi F, Tassinari E, Galvani A, Toni A. The influence of the centre of rotation on implant survival using a modular stem hip prosthesis. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1513–1518.

Traina F, De Fine M, Tassinari E, Sudanese A, Calderoni PP, Toni A. Modular neck prostheses in DDH patients: 11-year results. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16:14–20.

Vassan UT, Sharma S, Chowdary KP, Bhamra MS. Uncemented metal-on-metal acetabular component: follow-up of 112 hips for a minimum of 5 years. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:470–478.

Weiss RJ, Hailer NP, Stark A, Kärrholm J. Survival of uncemented acetabular monoblock cups: evaluation of 210 hips in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:214–219.

Yeung E, Bott PT, Chana R, Jackson MP, Holloway I, Walter WL, Zicat BA, Walter WK. Mid-term results of third-generation alumina-on-alumina ceramic bearings in cementless total hip arthroplasty: a ten-year minimum follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:138–144.

Yoon JP, Le Duff MJ, Takamura KM, Hodge S, Amstutz HC. Mid-to-long term follow-up of Transcend metal-on-metal versus Interseal metal-on-polyethylene bearings in total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2011;21:571–576.

Zijlstra WP, Cheung J, Sietsma MS, van Raay JJ, Deutman R. No superiority of cemented metal-on-metal vs metal-on-polyethylene THA at 5-year follow-up. Orthopedics. 2009;32:479.

Zijlstra WP, van Raay JJ, Bulstra SK, Deutman R. No superiority of cemented metal-on-metal over metal-on-polyethylene THA in a randomized controlled trial at 10-year follow-up. Orthopedics. 2010;33:154.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kay Daugherty, Campbell Foundation medical editor, for her aid in preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

One of the authors (WMM) receives royalty payments, during the study period, an amount of USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from B Braun/Aesculap Inc (Center Valley, PA, USA) and less than USD 10,000 from Elsevier Inc (Philadelphia, PA, USA); receives USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 as a consultant for B Braun/Aesculap Inc and less than USD 10,000 from Medtronic Inc (Memphis, TN, USA); receives research funding, during the study period, an amount of less than USD 10,000 from B Braun/Aesculap Inc and less than USD 10,000 Stryker Inc (Mahwah, NJ, USA); and serves on the editorial boards for the Journal of Arthroplasty, The Knee, the International Journal of Orthopaedics, and The Journal of Long Term Effects of Medical Implants. One of the authors (MAW) receives institutional funding in the amount of less than USD 10,000 from Biomet, Inc (Warsaw, IN, USA), USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from CeramTec GmbH (Lauf, Germany), and material support from Zimmer Inc (Warsaw, Inc, USA) and B Braun/Aesculap AG. He is an unpaid consultant for Endolab GmbH and a paid consultant receiving an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Irwing Fritche Urquhart & Moore LLC (New Orleans, LA, USA). One of the authors (MPL) owns Zimmer Holdings, Inc stock but received no payments during the study period.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

This work was performed at Rush University, Chicago, IL, USA; and Campbell Clinic/University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN, USA.

About this article

Cite this article

Mihalko, W.M., Wimmer, M.A., Pacione, C.A. et al. How Have Alternative Bearings and Modularity Affected Revision Rates in Total Hip Arthroplasty?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472, 3747–3758 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3816-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3816-2