Abstract

Purpose of Review

To provide a comprehensive overview on the evaluation and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) using evidence from literature.

Recent Findings

Evidence indicates efficacy for some non-pharmacological techniques including education of caregivers and cognitive stimulation therapy and pharmacological agents like antidepressant and antipsychotics for the management of BPSD. The use of antipsychotics has generated controversy due to the recognition of their serious adverse effect profile including the risk of cerebrovascular adverse events and death.

Summary

BPSD is associated with worsening of cognition and function among individuals with dementia, greater caregiver burden, more frequent institutionalization, overall poorer quality of life, and greater cost of caring for these individuals. Future management strategies for BPSD should include the use of technology for the provision of non-pharmacological interventions and the judicious use of cannabinoids and interventional procedures like ECT for the management of refractory symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) also known as neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia (NPS) include a wide-ranging group of psychological reactions, psychiatric symptoms, and behaviors that are unsafe, disruptive, and confound the care of the individual with dementia in a given environment [1]. Evidence indicates that BPSD tend to occur in approximately one-third of community-dwelling individuals who have a diagnosis of dementia [2]. The prevalence of BPSD increases to almost 80% among individuals with dementia who reside at skilled nursing facilities [3]. Jost and Grossberg in their study found that BPSD occurred in approximately 72% of individuals more than 2 years prior to the formal diagnosis of dementia, with the prevalence of BPSD rising to almost 81%, 10 months after the actual diagnosis of dementia was made [4]. BPSD, unlike cognitive symptoms of dementia which decline over time, tend to fluctuate with agitation being the most persistent symptom [5,6,7].

Prevalence

The most commonly noted BPSD is apathy and it often occurs early in the illness, and remains stable through the course of the illness [8]. Among individuals with dementia, commonly noted delusions include false beliefs of theft, infidelity, and misidentification syndromes. Disinhibition is noted in approximately one-third of individuals with dementia [8]. Visual hallucination is the most common form of hallucination among individuals with dementia [8]. Irritability and mood lability become more prevalent as the dementia progresses [8]. Table 1 provides the prevalence rates for common BPSD [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. A family history of depression appears to increase the risk for developing a major depressive episode among individuals with dementia [16].

Neurobiology

Emerging evidence indicates that BPSD occur due to the anatomical, functional, and biochemical changes that occur in the brain of individuals with dementia [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. They can also occur due to the presence of certain genes among individuals with dementia [16, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. BPSD can occur due to the individual’s premorbid personality [37, 38]. Table 2 highlights the various neurobiological changes that are associated with the development of BPSD [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

Consequences

BPSD are a common reason for referral of individuals with dementia for specialist care [39]. It has been noted that BPSD, especially paranoia, aggression, and sleep–wake cycle disturbances, contribute to substantial caregiver burden, increasing the risk for caregiver depression and institutionalization for the individual with dementia [40,41,42,43]. BPSD are associated with worsening of activities of daily living (ADLs), faster cognitive decline, and a poorer quality of life for individuals with dementia [2, 44, 45]. After adjusting for the severity of cognitive impairment and other comorbidities, BPSD add to the overall direct and indirect cost of care for individuals with dementia [46, 47].

Assessment

When assessing individuals with BPSD, obtaining collateral information from caregivers is essential [48]. This information will assist in determining the onset, the course of illness, and the differential diagnosis for BPSD [48]. Collateral information also enables the identification of risk and prognostic factors for BPSD. Additionally, it is important to evaluate the environmental triggers and psychosocial stressors as these may be triggers for the onset or worsening of BPSD. Furthermore, the assessment of comorbid medical disorders including pain syndromes, urinary tract infections, or metabolic disturbances is crucial as these conditions can trigger or worsen BPSD [48].

The use of standardized and validated assessment tools, like the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI), the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD), the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease-Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (CERAD-BRSD), Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale (DBBS), or the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (NRS), assists in identifying the different types of BPSD and their frequency and severity. These scales also aid in evaluating their progress and monitoring their response to management strategies. Kales et al. have proposed a structured approach called the DICE (Describe, Investigate, Create, and Evaluate) to assist in the assessment and management of BPSD [49].

Management

For the management of BPSD, both non-pharmacological and pharmacological strategies have been shown to be beneficial [50, 51••]. The most benefit in managing these difficult behaviors is obtained when non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions are combined [52••].

Non-Pharmacological Management

Available evidence suggests that in most situations, non-pharmacological strategies should be used as first-line option for the management of BPSD [53••]. Livingston et al., in their systematic review, found that the education of caregiver and residential care staff and cognitive stimulation therapy appear to be beneficial in the management of BPSD [54]. They found that visual changes in the environment and the unlocking of doors reduced wandering behaviors, but specialized dementia units were not consistently beneficial to individuals with BPSD. Brodaty and Arasartnam in their meta-analysis found that non-pharmacological interventions provided by the family caregivers tend to reduce the frequency and severity of BPSD (effect size = 0.34, P < 0.01) [55]. In addition, these interventions reduced the caregiver burden (effect size = 0.15, P = 0.006) [55]. Seitz et al. in their systematic review found statistically significant results in favor of staff training in behavioral management strategies, mental health consultation and treatment planning, exercise, recreational activities, music therapy, or other forms of sensory stimulation as part of non-pharmacological interventions on at least one measure of BPSD [56]. However, many of these studies had methodological limitations and 75% of the studies indicated a need for services from outside of the facility in addition to significant time commitments from the nursing staff for these strategies to be implemented. A recent international Delphi consensus process provided the highest priority to the DICE intervention which evaluates BPSD using a structured method approach, including the assessment of underlying etiologies, planning of care, and follow-up monitoring followed by training and empowerment of caregivers [57].

Pharmacological Management

Emerging evidence indicates efficacy for antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, cholinesterase inhibitors, and memantine in the management of BPSD [52••]. The next section describes common medication classes that have shown benefit in the management of BPSD.

Antipsychotics

Ballard et al. in their meta-analysis found that risperidone and olanzapine improved aggression among individuals with BPSD when compared to placebo [58]. Additionally, individuals who were treated with risperidone had significant improvement in psychosis when compared to placebo. Schneider et al. in their meta-analysis identified efficacy for aripiprazole and risperidone in the management of individuals with BPSD [59].

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of outpatients with Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and psychosis, aggression, or agitation who were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or placebo, investigators found no significant difference among the active agents when compared to placebo with regard to the time to discontinuation of treatment for any reason [60]. However, olanzapine and risperidone were favored when compared to quetiapine and placebo in the median time to discontinuation of treatment due to a lack of efficacy. When compared to active agents, time to discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events or intolerability favored placebo. Yury and Fisher found a net effect size of 0.45 for atypical antipsychotics and 0.32 for placebo in their meta-analysis that evaluated risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine when compared to placebo for the management of BPSD [61].

Tampi et al. in their systematic review found a total of 12 meta-analyses that evaluated the efficacy of antipsychotic medications in individuals with BPSD [62]. In this review, 10 of the 12 meta-analyses evaluated atypical antipsychotic medications, whereas 2 meta-analyses evaluated typical antipsychotics. The typical antipsychotics were found to have modest efficacy when used among individuals with dementia, with no superiority noted for any particular medication in this drug class. In addition, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole showed modest efficacy when used in individuals with dementia including AD. Quetiapine was found to have limited efficacy when used in individuals with dementia. The authors noted that psychotic symptoms, aggression, agitation, and more severe symptoms appear to be particularly responsive to these medications. They noted smaller effects for less severe dementia and those individuals receiving outpatient treatment.

A recent network meta-analysis that included data from 17 studies found that when compared to placebo, the use of aripiprazole, quetiapine, and risperidone was associated with improvements on BPSD [63••]. The investigators did not find any significant difference in effectiveness between the atypical antipsychotics.

Antidepressants

Sertraline and citalopram were associated with a reduction in symptoms of agitation when compared to placebo, in a meta-analysis by Seitz et al. [64]. The authors found that the two studies of trazodone did not detect any difference in BPSD when compared to haloperidol. Both Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and trazodone appear to be well tolerated when compared to placebo, typical antipsychotics, and atypical antipsychotics. Henry et al. in their literature review found a total of 8 trials of SSRIs and 3 trials of trazodone that showed some benefit in the management of BPSD [65]. In 14 of the 19 trials that were reviewed, the antidepressants were well tolerated.

Anticonvulsants

Lonergan et al. in their Cochrane database review found that low-dose sodium valproate was ineffective for the management of BPSD, whereas high-dose divalproex sodium was associated with serious and unacceptable adverse effects [66]. Konovalov et al. in their literature review studied a total of seven RCTs that evaluated the use of mood stabilizers for the management of BPSD. Only one study of carbamazepine showed a statistically significant benefit for the drug-treated group when compared to the placebo, whereas 5 of the 7 studies showed no significant differences among the groups [67]. Adverse effects were noted to be more frequent among the medication-treated groups when compared to the placebo groups in majority of the studies.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Trinh et al. in their meta-analysis found that individuals who were treated with cholinesterase inhibitors had modest improvements in BPSD when compared to individuals treated with placebo [68]. The investigators did not find any difference in efficacy between the different cholinesterase inhibitors. Maidment et al. in their meta-analysis found that individuals who were treated with memantine had modest improvements in BPSD when compared to individuals who were prescribed placebo [69]. Sedation was the only adverse event noted more frequently among the drug-treated group when compared to placebo in these studies.

Benzodiazepines

Tampi and Tampi in their systematic review found only five controlled trials that evaluated the use of benzodiazepines for the management of BPSD [70]. These trials were of short duration and with a limited number of subjects. The efficacy data was limited, and the adverse effect profile was not benign with the use of benzodiazepines.

Analgesics

In a systematic review, Tampi et al. identified a total of 3 RCTs that evaluated the use of analgesics among individuals with BPSD [71]. There was evidence of benefit in reducing BPSD in all 3 RCTs. Available evidence indicated that the analgesics appear to be well tolerated in these studies. Supasitthumrong et al. in their systematic review included information from 24 articles [72•]. Data was considered from 15 original case series/case reports that included 87 individuals who were prescribed gabapentin, and 6 who were given pregabalin. In 12 of 15 papers, drug treatment was found to be effective in majority of cases.

Cannabinoids

Emerging evidence indicates efficacy of cannabinoids in the management of BPSD [73]. Tampi et al. in their review of the literature found a total of 8 reports that evaluated the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of BPSD [74]. The investigators included a total of 117 individuals with a diagnosis of dementia, with 58% of these individuals having Alzheimer’s type dementia. A total of 7 of the 8 studies indicated improvement in BPSD symptoms with the use of cannabinoids. The symptoms that showed improvement included agitation, aggression, impulsivity, nocturnal restlessness, wandering, and poor sleep. In 4 of the 8 studies, there were no significant adverse effects noted with the use of a cannabinoids. In a systematic review that included data from 12 studies, Hillen et al. found that dronabinol (data from 3 studies) and THC (data from 1 study) improved a variety of symptoms of BPSD [75••]. Sedation was the most common adverse effect reported in these studies.

A Recent Meta-analysis

In a network meta-analysis of 146 RCTs that involved 44,873 individuals with BPSD, Jin and Liu found that aripiprazole, haloperidol, quetiapine, and risperidone showed the most significant efficacy in the management of BPSD, whereas memantine, galantine, and donepezil were thought to have modest effectiveness [76••].

Interventional Procedures

Electroconvulsive Therapy

There is accumulating evidence that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a promising option in the treatment of severe and refractory BPSD [77, 78]. Tampi et al. in their literature review found that there were 20 published reports on the use of ECT for the management of BPSD that included data from a total of 172 individuals with dementia [79]. Majority of the individuals had AD (40%). Bitemporal followed by right unilateral and bilateral were the most common electrode placements. It was noted that over 90% of the individuals responded to ECT treatments. Adverse effects were infrequent and when they occurred, were mild and transient. The most common adverse event noted was postictal confusion/memory impairment that was seen in approximately 15% of the individuals.

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation or Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Vacas et al. included data from 5 randomized, controlled clinical trials (RCTs) and 2 open-label clinical trial [80•]. The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was evaluated from 5 studies, whereas 2 studies evaluated the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Two of the 3 RCTs using rTMS showed statistically significant benefits in the management of BPSD, while the 2 studies evaluating tDCS did not find any efficacy for BPSD. A meta-analysis of four RCT studies did not find any evidence of efficacy for noninvasive brain stimulation techniques (rTMS and tDCS), with an overall effect of − 0.02. When the investigators used data from rTMS studies, a benefit was noted with an overall effect of − 0.58. Both rTMS and tDCS were well tolerated with adverse effects being mild and not clinically significant.

Concerns With Using Antipsychotic Among Individuals With BPSD

Cerebrovascular Adverse Events

Concerns about the cerebrovascular adverse events (CVAEs) with risperidone in clinical trials of older adults with dementia was raised for the first time by the Canadian Health Regulatory Agency in 2002 [81]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003 published similar warnings and required changes in the prescribing information for risperidone. In 2004, the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) issued a public advisory on the increased risk of CVAEs and mortality in older individuals with dementia who were receiving risperidone. In 2004, the UK’s Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) advised prescribers that risperidone and olanzapine should not be used to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia because of “clear evidence of an increased risk of strokes”.

In a post hoc analysis of pooled results from eleven randomized controlled trials of risperidone and olanzapine in individuals with dementia, Herrmann and Lanctot found an increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse events in the drug-treated group when compared to the placebo group [82]. The investigators also found that some of the increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse events could be accounted for by non-specific events that were not actual strokes. In the risperidone trials, there were a significant number of individuals with vascular and mixed dementias when compared to the olanzapine trials. However, data from two large observational studies found that there was no greater risk of stroke among older adults who were treated with risperidone and olanzapine when compared to those individuals who were treated with typical antipsychotics, or untreated individuals with dementia [83, 84]. A meta-analysis of population-based data found that there was no significant difference in the risk of stroke (P = 0.96) among individuals with dementia who were prescribed second-generation antipsychotics when compared to first-generation antipsychotics [85]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies found that there was increased risk of cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) with first-generation antipsychotics [odds ratio (OR) = 1.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.24–1.77] but not with second-generation antipsychotics (OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 0.74–2.30) [86]. The risk of CVA (OR = 1.17; 95% CI = 1.08–1.26) with the use of any antipsychotic among individuals with dementia was low.

Mortality

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found an increase in mortality with the use of atypical antipsychotics among individuals with dementia [81]. A numerical increase in mortality (1.6–1.7 times) among the drug-treated group was noted when compared to the placebo-treated group from 15 of the 17 placebo-controlled trials of olanzapine, aripiprazole, risperidone, or quetiapine. The deaths were either due to heart-related events (heart failure or sudden death) or infections (mainly pneumonia). A “Boxed Warning” describing the risk of death was added to the labeling of these drugs by the manufacturers, indicating that these drugs are not approved for the treatment of BPSD. More recently, similar changes to the labeling for typical antipsychotics have been added.

The risk of death was found to be greater among individuals who were treated with atypical antipsychotics when compared to placebo in a meta-analysis by Schneider et al. [87]. The investigators did not find any evidence for differential risks for individual drugs, severity of dementia, sample selection, or the diagnosis. Wang et al. in their retrospective cohort study found that conventional antipsychotic medications were associated with significantly higher adjusted risk of death when compared to atypical antipsychotics. This risk remained high for all time intervals studied (< 40 days to ≥ 180 days) and in all subgroups based on the presence or absence of dementia or of nursing home residency [88].

In a review by Mittal et al., the investigators found the risk of death to be about 1.2 to 1.6 times higher in the drug-treated group when compared to placebo group [81]. Data indicated that the risk for death is similar for typical and atypical antipsychotics. The risk of death was associated with older age, male gender, severe dementia, and functional impairment. The risk for death remained elevated for the first 30 days and for possibly up to 2 years.

A meta-analysis from 2018 found that the relative risk (RR) with the use of antipsychotic drugs was approximately 2 for all-cause mortality among older individuals [89•]. The risk period for mortality was highest from the outset and over the initial 0–180 days after starting their use. The risks for all-cause mortality were dose-related; risk increasing with increased doses. There was a small difference noted in the risks when using either the typical or atypical antipsychotics. The risk for mortality was significant and high for all users, including individuals with or without dementia.

A recent registry-based observational cohort study found that the use of antipsychotics at the time of dementia diagnosis was associated with increased mortality risk in the total cohort (hazard ratio = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.3–1.5) [90•]. Increased mortality risk was associated with the use of antipsychotics in individuals with AD, mixed dementia, unspecified dementia, and vascular dementia. A higher risk for mortality was found with typical antipsychotics among individuals with mixed and vascular dementia and with atypical antipsychotics among individuals with AD, mixed, unspecified, and vascular dementia. Furthermore, in patients with AD who had typical antipsychotics, a lower risk of death emerged in comparison with patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.

A Recent Meta-analysis

In a network meta-analysis, Watt et al. found that there was greater risk for cerebrovascular events associated with the use of antipsychotics (odds ratio [OR] = 2.12, number needed to harm [NNH] = 99) and falls associated with dextromethorphan-quinidine (OR = 4.16, NNH = 55) when compared to placebo [91••]. Among subgroup of individuals with AD, the use of antipsychotics was associated with greater risk of fracture when compared to anticonvulsants (OR = 54.1, NNH = 18). Anticonvulsants were associated with greater risk of death when compared to placebo (OR = 8.36, NNH = 35) and when compared to antidepressants (OR = 5.28, NNH = 47).

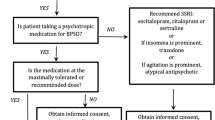

Possible Algorithm for Managing BPSD

Non-pharmacological strategies have been found to be beneficial to individuals with BPSD and to their caregivers [51••, 54, 55]. In addition, most guidelines recommend non-pharmacological strategies to be the primary intervention for the management of BPSD [53••]. Judicious pharmacotherapy trials can be initiated when the BPSD symptoms are not well managed with non-pharmacological strategies alone [92]. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in individuals with dementia provides a comprehensive document on the evaluation and management of BPSD [93]. Clinicians caring for individuals with BPSD should familiarize themselves with this document in order to follow this guideline and to appropriately care for individuals with BPSD.

As BPSD can emerge or worsen when there is a progression of cognitive decline, it is prudent to start a trial of cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine to slow down the process of cognitive decline among individuals with dementia [3]. If possible, the BPSD should then be grouped into different clusters based on the presenting symptoms i.e., psychotic cluster and mood cluster, and these clusters act as psycho-behavioral metaphors of primary psychiatric disorders e.g., psychotic disorders and mood disorders [39]. It is prudent to try and use medications that have known efficacy for similar behavioral clusters e.g., antipsychotics for the psychotic cluster and antidepressants for depressive symptoms in the mood cluster [94].

If symptoms of BPSD are not adequately managed by monotherapy medication trials, a judicious combination of medications can be tried e.g., an antidepressant with an antipsychotic medication or a mood stabilizer with an antipsychotic medication [92]. Prior to starting any new medication trial, those medications that have been found to be ineffective must be tapered and discontinued. Regular monitoring of benefits versus risks of using pharmacotherapy must be conducted to avoid unnecessary medication trials and minimize adverse effects. To minimize serious adverse events, injudicious medication combinations such as two antipsychotics or three or four different medication classes should be avoided. The duration of effective medication trials should be about 3–4 months of clinical stability, following which a trial of medication taper and discontinuation should be initiated [95]. Often multiple different medication trials either as monotherapy or in combination may be needed prior to the amelioration of symptoms [92]. For refractory symptoms of BPSD, cannabinoids and/or ECT should be considered [74, 79].

It is prudent to exercise caution when using antipsychotics among older adults with dementia as they are at high risk for developing serious adverse effects from these medications [81]. Individuals who are at high risk include those who are ≥ 85 years in age, have vascular or mixed dementias or active cerebrovascular or cardiovascular diseases, and significant impairments in activities of daily living. The use of antipsychotics may be justified in these high-risk individuals if the symptoms of BPSD are not sufficiently managed by other strategies [96]. It is also sensible to use the lowest effective dose of antipsychotics and for the shortest period of time when managing BPSD [81]. Potentially serious adverse events can be minimized by the close monitoring of risk factors for adverse outcomes, and their swift management.

There are two published algorithms for the management of BPSD [97•, 98••]. In the first algorithm from Canada, the authors recommend that after completion of a baseline assessment and discontinuation of medications that are potentially exacerbating the BPSD, sequential trials should be done using risperidone, aripiprazole or quetiapine, carbamazepine, citalopram, gabapentin, and prazosin [97•]. The algorithm also provides information regarding titration schedules for medications after adjustments for frailty, the use of ECT, the optimization of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, and the use of pro re nata (PRN) medications to manage BPSD. In the second algorithm from the Harvard South Shore, the authors propose three separate algorithms in emergent, urgent, and non-urgent settings [98••]. For emergent BPSD, the authors recommend using intramuscular (IM) olanzapine as first-line treatment (as IM aripiprazole which was previously favored is no longer available). Haloperidol injection is the recommended second choice, followed by possible consideration of an IM benzodiazepine. In urgent setting, the authors recommend using oral second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs)—aripiprazole and risperidone as first-line treatment. The next option could be prazosin, and ECT could be a final option. For non-emergent agitation, the authors recommend the following order of medications: trazodone, donepezil and memantine, antidepressants such as escitalopram and sertraline, SGAs, prazosin, and finally carbamazepine.

Conclusions

BPSD occur commonly among individuals with dementia. BPSD are associated with worse outcomes and greater burden of care among individuals with dementia. BPSD are thought to occur due to the interactions between underlying neuroanatomical and neurochemical changes in the brain and the individual’s premorbid personality. The evaluation of BPSD should include a thoughtful assessment of comorbidities, environmental conditions, and psychosocial stressors, as these factors can predispose and precipitate BPSD. The management of BPSD should start with non-pharmacological interventions. The possible benefits of prescribing medications for BPSD should always be carefully weighed against the possible risks of using these medications. Additionally, medications should only be prescribed within the recommended dose ranges to mitigate the risk of serious adverse events. Furthermore, the close monitoring of risk factors will reduce the occurrence of serious adverse events including cerebrovascular events and deaths. Future management paradigms for BPSD should include the use of technology for the provision of non-pharmacological interventions and the judicious use of cannabinoids and interventional procedures like ECT for the management of refractory symptoms.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Bharucha AJ, Rosen J, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG. Assessment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. CNS Spectr. 2002;7:797–802.

Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:708–14.

Margallo-Lana M, Swann A, O’Brien J, Fairbairn A, Reichelt K, Potkins D, et al. Prevalence and pharmacological management of behavioural and psychological symptoms amongst dementia sufferers living in care environments. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:39–44.

Jost BC, Grossberg GT. The evolution of psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a natural history study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1078–81.

Lyketsos CG, Olin J. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: overview and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:243–52.

Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Psychiatric phenomena in Alzheimer’s disease. I: Disorders of thought content. Br J Psychiatry 1990;157:72–6, 92–4.

Devanand DP, Jacobs DM, Tang MX, Del Castillo-Castaneda C, Sano M, Marder K, et al. The course of psychopathologic features in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:257–63.

Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, Gornbein J. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130–5.

Lee HB, Lyketsos CG. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: heterogeneity and related issues. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:353–62.

Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:129–41.

Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Psychiatric phenomena in Alzheimer’s disease. III: Disorders of mood. Br J Psychiatry 1990;157:81–6, 92–4.

Bassiony MM, Lyketsos CG. Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: review of the brain decade. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:388–401.

Black B, Muralee S, Tampi RR. Inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:155–62.

Rose KM, Lorenz R. Sleep disturbances in dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36:9–14.

White H, Pieper C, Schmader K. The association of weight change in Alzheimer’s disease with severity of disease and mortality: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1223–7.

Pearlson GD, Ross CA, Lohr WD, Rovner BW, Chase GA, Folstein MF. Association between family history of affective disorder and the depressive syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:452–6.

Zubenko GS, Moossy J, Martinez AJ, Rao G, Claassen D, Rosen J, et al. Neuropathologic and neurochemical correlates of psychosis in primary dementia. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:619–24.

Victoroff J, Zarow C, Mack WJ, Hsu E, Chui HC. Physical aggression is associated with preservation of substantia nigra pars compacta in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:428–34.

Farber NB, Rubin EH, Newcomer JW, Kinscherf DA, Miller JP, Morris JC, et al. Increased neocortical neurofibrillary tangle density in subjects with Alzheimer disease and psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1165–73.

Tekin S, Mega MS, Masterman DM, Chow T, Garakian J, Vinters HV, et al. Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:355–61.

Förstl H, Besthorn C, Burns A, Geiger-Kabisch C, Levy R, Sattel A. Delusional misidentification in Alzheimer’s disease: a summary of clinical and biological aspects. Psychopathology. 1994;27:194–9.

Kotrla KJ, Chacko RC, Harper RG, Doody R. Clinical variables associated with psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1377–9.

Starkstein SE, Vázquez S, Petracca G, Sabe L, Migliorelli R, Tesón A, et al. A SPECT study of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1994;44:2055–9.

Mentis MJ, Weinstein EA, Horwitz B, McIntosh AR, Pietrini P, Alexander GE, et al. Abnormal brain glucose metabolism in the delusional misidentification syndromes: a positron emission tomography study in Alzheimer disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:438–49.

Sultzer DL, Mahler ME, Mandelkern MA, Cummings JL, Van Gorp WG, Hinkin CH, et al. The relationship between psychiatric symptoms and regional cortical metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:476–84.

Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, Kitagaki H, Sasaki M, Ikejiri Y, et al. Alteration of regional cerebral glucose utilization with delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:433–9.

Cummings JL, Back C. The cholinergic hypothesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6:S64-78.

Strauss ME, Ogrocki PK. Confirmation of an association between family history of affective disorder and the depressive syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1340–2.

Lyketsos CG, Tune LE, Pearlson G, Steele C. Major depression in Alzheimer’s disease. An interaction between gender and family history. Psychosomatics 1996;37:380–4.

Bacanu S-A, Devlin B, Chowdari KV, DeKosky ST, Nimgaonkar VL, Sweet RA. Heritability of psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:624–7.

Ballard C, Massey H, Lamb H, Morris C. Apolipoprotein E: non-cognitive symptoms and cognitive decline in late onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:273–4.

Cacabelos R, Rodríguez B, Carrera C, Caamaño J, Beyer K, Lao JI, et al. APOE-related frequency of cognitive and noncognitive symptoms in dementia. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1996;18:693–706.

Holmes C, Arranz MJ, Powell JF, Collier DA, Lovestone S. 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor polymorphisms and psychopathology in late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1507–9.

Sukonick DL, Pollock BG, Sweet RA, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, Klunk WE, et al. The 5-HTTPR*S/*L polymorphism and aggressive behavior in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1425–8.

Sweet RA, Nimgaonkar VL, Kamboh MI, Lopez OL, Zhang F, DeKosky ST. Dopamine receptor genetic variation, psychosis, and aggression in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1335–40.

Holmes C, Smith H, Ganderton R, Arranz M, Collier D, Powell J, et al. Psychosis and aggression in Alzheimer’s disease: the effect of dopamine receptor gene variation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:777–9.

Meins W, Frey A, Thiesemann R. Premorbid personality traits in Alzheimer’s disease: do they predispose to noncognitive behavioral symptoms? Int Psychogeriatr. 1998;10:369–78.

Chatterjee A, Strauss ME, Smyth KA, Whitehouse PJ. Personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:486–91.

Lawlor B. Managing behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:463–5.

Coen RF, Swanwick GR, O’Boyle CA, Coakley D. Behaviour disturbance and other predictors of carer burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:331–6.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, Bray T, Castellon S, Masterman D, et al. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:210–5.

O’Donnell BF, Drachman DA, Barnes HJ, Peterson KE, Swearer JM, Lew RA. Incontinence and troublesome behaviors predict institutionalization in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1992;5:45–52.

Steele C, Rovner B, Chase GA, Folstein M. Psychiatric symptoms and nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1049–51.

Stern Y, Albert M, Brandt J, Jacobs DM, Tang MX, Marder K, et al. Utility of extrapyramidal signs and psychosis as predictors of cognitive and functional decline, nursing home admission, and death in Alzheimer’s disease: prospective analyses from the Predictors Study. Neurology. 1994;44:2300–7.

Stern Y, Mayeux R, Sano M, Hauser WA, Bush T. Predictors of disease course in patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1987;37:1649–53.

Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, Noy S. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:403–8.

Murman DL, Chen Q, Powell MC, Kuo SB, Bradley CJ, Colenda CC. The incremental direct costs associated with behavioral symptoms in AD. Neurology. 2002;59:1721–9.

Robert PH, Verhey FRJ, Byrne EJ, Hurt C, De Deyn PP, Nobili F, et al. Grouping for behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia: clinical and biological aspects. Consensus paper of the European Alzheimer disease consortium. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:490–6.

Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG, Detroit Expert Panel on Assessment and Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:762–9.

Lanari A, Amenta F, Silvestrelli G, Tomassoni D, Parnetti L. Neurotransmitter deficits in behavioural and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:158–65.

•• Gerlach LB, Kales HC. Managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36:315–27. This is an excellent narrative review on the assessment and management of BPSD.

•• Magierski R, Sobow T, Schwertner E, Religa D. Pharmacotherapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: state of the art and future progress. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1168. This paper reviews the current evidence for the management of BPSD and its limitations. It also discusses ongoing clinical trials and future therapeutic options for BPSD.

•• Dyer SM, Harrison SL, Laver K, Whitehead C, Crotty M. An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30:295–309. This excellent systematic evaluates data from systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of BPSD.

Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG, Old Age Task Force of the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1996–2021.

Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:946–53.

Seitz DP, Brisbin S, Herrmann N, Rapoport MJ, Wilson K, Gill SS, et al. Efficacy and feasibility of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in long term care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:503-506.e2.

Kales HC, Lyketsos CG, Miller EM, Ballard C. Management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in people with Alzheimer’s disease: an international Delphi consensus. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:83–90.

Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD003476.

Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:191–210.

Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Davis SM, Hsiao JK, Ismail MS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525–38.

Yury CA, Fisher JE. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of behavioural problems in persons with dementia. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:213–8.

Tampi RR, Tampi DJ, Balachandran S, Srinivasan S. Antipsychotic use in dementia: a systematic review of benefits and risks from meta-analyses. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7:229–45.

•• Yunusa I, Alsumali A, Garba AE, Regestein QR, Eguale T. Assessment of reported comparative effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2: e190828. This outstanding network meta-analysis evaluates the comparative effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of BPSD.

Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, Gruneir A, Herrmann N, Rochon P. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD008191.

Henry G, Williamson D, Tampi RR. Efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, a literature review of evidence. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26:169–83.

Lonergan ET, Cameron M, Luxenberg J. Valproic acid for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD003945.

Konovalov S, Muralee S, Tampi RR. Anticonvulsants for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:293–308.

Trinh N-H, Hoblyn J, Mohanty S, Yaffe K. Efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional impairment in Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;289:210–6.

Maidment ID, Fox CG, Boustani M, Rodriguez J, Brown RC, Katona CL. Efficacy of memantine on behavioral and psychological symptoms related to dementia: a systematic meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:32–8.

Tampi RR, Tampi DJ. Efficacy and tolerability of benzodiazepines for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;29:565–74.

Tampi RR, Hassell C, Joshi P, Tampi DJ. Analgesics in the management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a perspective review. Drugs Context. 2017;6: 212508.

• Supasitthumrong T, Bolea-Alamanac BM, Asmer S, Woo VL, Abdool PS, Davies SJC. Gabapentin and pregabalin to treat aggressivity in dementia: a systematic review and illustrative case report. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:690–703. This systematic review evaluates the use of gabapentin and pregabalin for BPSD symptoms of agitation or aggression.

Mueller A, Fixen DR. Use of cannabis for agitation in patients with dementia. Sr Care Pharm. 2020;35:312–7.

Tampi RR, Young JJ, Tampi DJ. Cannabinoids for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2018;8:211–3.

•• Hillen JB, Soulsby N, Alderman C, Caughey GE. Safety and effectiveness of cannabinoids for the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: a systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2019;10:2042098619846993. This excellent systematic review assesses the efficacy and safety of cannabinoids for the management of BPSD.

•• Jin B, Liu H. Comparative efficacy and safety of therapy for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systemic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2019;266:2363–75. This is an excellent systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of all the available interventions for the management of BPSD.

Glass OM, Forester BP, Hermida AP. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for treating agitation in dementia (major neurocognitive disorder) - a promising option. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:717–26.

Hermida AP, Tang Y-L, Glass O, Janjua AU, McDonald WM. Efficacy and safety of ECT for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): a retrospective chart review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020;28:157–63. This retrospective chart review evaluates the efficacy and safety of ECT for the management of BPSD.

Tampi RR, Tampi DJ, Young J, Hoq R, Resnick K. The place for electroconvulsive therapy in the management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2019.

• Vacas SM, Stella F, Loureiro JC, Simões do Couto F, Oliveira-Maia AJ, Forlenza OV. Noninvasive brain stimulation for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019;34:1336–45. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effects of rTMS or tDCS on BPSD.

Mittal V, Kurup L, Williamson D, Muralee S, Tampi RR. Risk of cerebrovascular adverse events and death in elderly patients with dementia when treated with antipsychotic medications: a literature review of evidence. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26:10–28.

Herrmann N, Lanctôt KL. Do atypical antipsychotics cause stroke? CNS Drugs. 2005;19:91–103.

Gill SS, Rochon PA, Herrmann N, Lee PE, Sykora K, Gunraj N, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and risk of ischaemic stroke: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:445.

Liperoti R, Gambassi G, Lapane KL, Chiang C, Pedone C, Mor V, et al. Cerebrovascular events among elderly nursing home patients treated with conventional or atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1090–6.

Rao A, Suliman A, Story G, Vuik S, Aylin P, Darzi A. Meta-analysis of population-based studies comparing risk of cerebrovascular accident associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotic prescribing in dementia. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2016;25:289–98.

Hsu W-T, Esmaily-Fard A, Lai C-C, Zala D, Lee S-H, Chang S-S, et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of cerebrovascular accident: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:692–9.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934–43.

Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Fischer MA, Mogun H, Solomon DH, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2335–41.

Ralph SJ, Espinet AJ. Increased all-cause mortality by antipsychotic drugs: updated review and meta-analysis in dementia and general mental health care. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2018;2:1–26. This meta-analysis includes evidence from general mental health studies showing that antipsychotic drugs precipitate excessive mortality among individuals with dementia.

• Schwertner E, Secnik J, Garcia-Ptacek S, Johansson B, Nagga K, Eriksdotter M, et al. Antipsychotic treatment associated with increased mortality risk in patients with dementia. A registry-based observational cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:323–329.e2. This registry-based cohort study evaluated the risk for all-cause mortality among individuals with dementia who are treated with antipsychotics.

•• Watt JA, Goodarzi Z, Veroniki AA, Nincic V, Khan PA, Ghassemi M, et al. Safety of pharmacologic interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:212. This systematic review and network meta-analysis evaluated the safety of pharmacological agents used for the management of BPSD.

Tampi RR, Williamson D, Muralee S, Mittal V, McEnerney N, Thomas J, et al. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: part II - treatment. 2011;9.

Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, Hilty DM, Horvitz-Lennon M, Jibson MD, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:543–6.

Meyers BS, Jeste DV. Geriatric psychopharmacology: evolution of a discipline. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1416–24.

Ballard CG, Gauthier S, Cummings JL, Brodaty H, Grossberg GT, Robert P, et al. Management of agitation and aggression associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:245–55.

Tampi RR, Tampi DJ, Rogers K, Alagarsamy S. Antipsychotics in the management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: maximizing gain and minimizing harm. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2020;10:5–8.

• Davies SJ, Burhan AM, Kim D, Gerretsen P, Graff-Guerrero A, Woo VL, et al. Sequential drug treatment algorithm for agitation and aggression in Alzheimer’s and mixed dementia. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32:509–23. This article provides an algorithm-based approach for drug treatment of agitation/aggression among individuals with Alzheimer’s/mixed dementia.

•• Chen A, Copeli F, Metzger E, Cloutier A, Osser DN. The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113641. This excellent article provides an update of the previously published algorithms for the use of psychopharmacologic agents in the management of BPSD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Geriatric Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tampi, R.R., Bhattacharya, G. & Marpuri, P. Managing Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) in the Era of Boxed Warnings. Curr Psychiatry Rep 24, 431–440 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01347-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01347-y