Abstract

Musculoskeletal pain (MP) is common in the general population and has been associated with anxiety in several ways: (a) muscle tension is included as a part of the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, (b) pain can be a common symptom and a good indicator of an anxiety disorder, (c) anxiety is an independent predictor of quality of life in patients with chronic MP, (d) anxiety leads to higher levels of pain chronification, and (e) fear, anxiety, and avoidance are related to MP. The objective of this article is to explore the mechanisms underlying the relation between anxiety disorders and musculoskeletal pain as well as its management. We have also highlighted the role of spirituality and religiosity in MP treatment. We found some similarities between proposed mechanisms and explicative models for both conditions as well as an overlapping between the treatments available. The recognition of this association is important for professionals who deal with chronic pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain (MP) is common in the general population. Studies have reported a MP prevalence varying from 15% to 47% [1–4] and a chronic widespread pain (CWP) prevalence varying between 11.4% and 24% [4].

Although the definition of MP remains uncertain, Woolf and Pfleger [5] defined musculoskeletal conditions as “a diverse group with regard to pathophysiology but which are linked anatomically and by their association with pain and impaired physical function. They encompass a spectrum of conditions, from those of acute onset and short duration to lifelong disorders.”

In fact, MP covers a wide range of conditions, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, low back pain, fibromyalgia, and primary or secondary headaches. It can be widespread or regionalized and could affect all of the body, predominantly the neck, lower back, shoulders, elbows, knees, and fingers. According to Carnes et al [6], more than 75% of patients have pain in multiple sites instead of a single site.

Evidence [4, 6] shows that MP has the following risk factors: age, gender, smoking, low education, low physical activity, poor social interaction, low family income, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, psychological distress, performing manual work, being a recent immigrant, being non-Caucasian, and not married.

MP seems to have a great impact on physical and mental health problems and, therefore, may significantly affect quality of life. Some surveys [5] point to a 5% prevalence of physical disabilities caused by a musculoskeletal condition in the general population with a huge societal impact such as work disability and utilization of health care services.

Mental health problems such as depression and anxiety seem to have a great impact on the prevalence and also the disability of MP.

Anxiety disorder is a very common condition with an estimated lifetime prevalence averaging approximately 16% [7]. These anxiety aspects have been linked to MP in several ways:

-

(a)

Muscle tension is included as a part of the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) according to the DSM IV [8]

-

(b)

Pain can be a common symptom and a good indicator of an anxiety disorder, particularly GAD [9]

-

(c)

Anxiety is an independent predictor of quality of life in patients with chronic MP [10]

-

(d)

Anxiety leads to higher levels of chronification [11], more severe pain, and long-lasting attacks in migraine patients

-

(e)

Fear, anxiety, and avoidance are related to MP [12].

Symptoms such as muscle tension, body soreness, and headaches are common not only in anxiety patients but also in some conditions such as fibromyalgia [13] and migraine [11, 14]. All these disorders seem to be somewhat connected. For instance, those who suffer from chronic pain and also have an anxiety disorder may have a lower tolerance for pain [15], people with anxiety disorders may be more worried about their health and more fearful of medication side effects [16], and they may also have lower pain thresholds than those without anxiety [17].

The objective of this article is to explore the mechanisms underlying the relation between anxiety disorders and musculoskeletal pain as well as its management.

Mechanisms of Anxiety and Musculoskeletal Pain

There are many mechanisms proposed for the etiopathology of musculoskeletal pain. Interestingly, some of these factors are overlapped by anxiety and fear. We will discuss some of these overlapping factors.

Genetics

Several studies have reported an association between catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism, pain sensitivity, and musculoskeletal pain [18, 19]. The same association is verified in anxiety disorders. There is a relation between COMT polymorphism and phobic anxiety, anxiety vulnerability, generalized anxiety disorder, and fear processing [20–22].

Neurotransmitters

The role of neurotransmitters also seems to overlap in both conditions. For instance, lower levels of serotonin have been associated with musculoskeletal pain [23] and also with anxiety [24]. The same seems to happen with dopamine, in which lower levels seem to be associated with MP and anxiety [25, 26].

Stressful Life Events

There is a relationship between stressful life events, anxiety, and also MP [27, 28].

Sex

Women seem to be more vulnerable and to have a higher prevalence of MP, fear, and anxiety [29, 30].

Association Between Anxiety, Fear, and Musculoskeletal Pain

Several studies have assessed the connections between anxiety, fear, and musculoskeletal pain.

Gore et al [31] have evaluated 101,294 persons categorized as chronic low back pain patients (CLBPP) and controls. They found that CLBPP have great psychiatric comorbidity, such as depression (13.0% CLBPP vs 6.1% controls), anxiety (10.0% CLBPP vs 3.4% controls ) and sleep disturbances (8.0% CLBPP vs 3.4% controls ). In addition, those with CLBPP also have a greater utilization of health services.

These results seem to persist in all ages. Knook et al [32] found that 21% of their pediatric sample with unexplained chronic pain had psychiatric disorders, predominantly anxiety disorders (18%).

Regarding anxiety and pain outcomes, Asmundson et al [33] have investigated 4 groups of students: (a) those with both high trauma-related stress and social anxiety symptom scores (TRS/SAS), (b) only high trauma-related stress symptom scores (TRS), (c) only high social anxiety symptom scores (SAS), or (d) neither (N). They found that the TRS/SAS group had significantly higher scores on all fear of pain measures, anxiety, sensitivity, and illness/injury sensitivity than any other group.

Greenberg and Burns [34] have evaluated chronic musculoskeletal pain patients who underwent cold pressor and mental arithmetic tasks while cardiovascular, self-report, and behavior indexes were recorded. As a result, they found that the effects of pain anxiety on task responses were accounted for by anxiety sensitivity.

Bair et al [35•] have evaluated 500 patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patients with pain and both depression and anxiety experienced the greatest pain severity and pain-related disability. In addition, patients with psychiatric comorbidity have more disability days.

Similar results were obtained by Carleton et al [36]. They have used the Waddell’s sign to indicate pain-related psychological distress in chronic low back pain patients. As a result, patients with more than 2 of Waddell’s symptoms reported higher levels of depressive symptoms, pain-related anxiety, fear, catastrophizing, and pain intensity. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in functional capacity.

Beneciuk et al [37] have evaluated the role of pain catastrophizing on pain intensity. They found that pain catastrophizing contributed specifically to evoked pain intensity ratings during neurodynamic testing for the median nerve of healthy subjects.

Jensen et al [38] have studied the role of anxiety in care-seeking for musculoskeletal pain. They found that somatization and health anxiety were associated with seeking care for back pain.

Anxiety seems also to predict lower quality of life in MP patients. Orenius et al [10] found that anxiety at baseline predicted the quality of life of MP patients after one year of follow-up.

Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain

Fear is the emotional reaction to a specific, identifiable, and immediate threat [39]. Fear has its nature in protecting the individual from impending danger, promoting a self-defense associated with the ‘fight or flight’ response [40].

Anxiety, in contrast to fear, is a future-oriented affective state and the source of threat is more elusive without a clear focus [41], through hyper vigilance, which occurs when the individual engages in environmental scanning for potential sources of threat.

The components of anxiety are somewhat similar to those of fear, but less intense. Anxiety is associated with preventative behaviors, including avoidance [42]. The distinction between fear and anxiety may not be evident, and these terms are frequently used interchangeably [43].

The fear and anxiety responses can be physiological (increase muscle tension), behavioral (escape and avoidance behavior), as well as cognitive (catastrophizing thoughts). While in pain, patients’ fears and phobias are described, such as fear of pain, fear of work-related activities, fear of movement, and fear of (re)injury. Some authors [44] believe that the pain-related fear could be more disabling than pain itself.

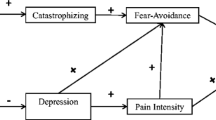

This fear-avoidance model of pain was first described by Lethem et al [45] in 1983 in “the fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception” and proposed as a model for chronic low back pain by Vlaeyen and Linton [12] in 2000 and by Leeuw et al [41] in 2007 (Fig. 1).

The fear-avoidance model of pain (adapted from Leeuw et al. [41])

The fear-avoidance model consists of nonthreatening acute pain (low fear) and catastrophically (mis)interpreted pain [41]. When nonthreatening acute pain is perceived, patients usually maintain normal activity, and functional recovery is achieved. A vicious cycle is initiated when catastrophically (mis)interpreted pain begins. Some dysfunctional interpretations could lead to pain-related fear, and some safety-seeking behaviors (avoidance/escape and hypervigilance). These fears may be adaptive in the acute pain stage, but may worsen the course of the disorder in the case of long-lasting pain. As a result, disability and disuse may appear and also lower the threshold at which subsequent pain will be experienced.

According to this model, several aspects can impact pain experience; pain severity, pain catastrophizing, attention to pain, avoidance behavior, disuse, and disability. Anxiety sensitivity has been included in the fear-avoidance model as a vulnerability factor to explain individual differences in fear.

The Past-Present-Future Model of Musculoskeletal Pain

Another way to understand the role of anxiety in pain is the proposed “Past-Present-Future model of musculoskeletal pain” (Fig. 2).

According to this model, considering that sense perception in humans is within the present time, consciousness is experienced as being part of the present, exactly in this moment. Some facts that have already happened could be remembered and some facts that possibly will be happening in the near future could be anticipated by this consciousness (Fig. 2a).

Nevertheless, if a negative life event is re-experienced or there is a negative perspective of a future event, a catastrophizing experience is felt. Therefore, sense perception, brain responses, and the physiological system are ready for releasing defense mechanisms, such as the ‘flight or fight response’. As a result, the individual may re-experience or even anticipate this scenario as a threat, actually happening at the current time (Fig. 2b).

General Treatment for Musculoskeletal Pain

When anxiety disorders are associated with MP, a specific treatment strategy should be planned. Usually 2 complementary strategies could be used: nonpharmacological and pharmacological [46].

Nonpharmacological

First, a good nonpharmacological plan should be performed. Some options available are exercise, physiotherapy, herbal remedies, acupuncture, sensory stimulations, education and behavioral interventions [46, 47].

Pharmacological

Pharmacotherapy is also a key therapeutic option for a comprehensive and successful pain management. According to a recent review [48], there is evidence that tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and dual serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are effective for musculoskeletal pain. Some studies suggest that the anti-seizure medications (pregabalin and gabapentin) and the analgesic tramadol are also effective.

Treating Musculoskeletal Pain in Anxiety Patients

In some situations, as reported throughout this article, there is an overlap between anxiety, fear-avoidance, and MP (Figs. 1 and 3). For these patients, some particularities of the treatment will be discussed:

Caffeine Consumption

Patients with anxiety should limit caffeine, which can trigger panic attacks and worsen anxiety symptoms [49]. Excessive intake of caffeine is recognized as an aggravating factor of headaches [50] but not for other pain conditions [51]. Avoiding caffeine late in the day and at night may also help to promote a more efficient sleep [52], which is related to anxiety.

Sleep Patterns

Some studies have shown that a restorative sleep has a pivotal role in pain improvement [53, 54] and anxiety [55]. Bigatti et al [54] found that in their sample, sleep problems predicted pain and pain predicted physical functioning, suggesting a critical role of sleep in fibromyalgia syndrome symptoms.

Physical Exercise

Regular exercise strengthens muscles, reduces stiffness, improves flexibility, and improves mood and self-esteem. Patients with mild disease may have a self-limiting and reversible problem usually helped by encouragement of aerobic-based exercises [56]. In patients with anxiety, exercise seems to reduce anxious symptoms [57] and possibly booster the improvement on musculoskeletal pain.

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) is an effective therapy used to treat anxiety disorders [58] as well as chronic pain conditions [59]. Morley et al [59] found in a systematic review that active psychological treatments such as CBT are effective in chronic pain and can change measures of pain experience, mood/affect, cognitive coping, pain behavior, and social role function. In another recent systematic review, Hofmann and Smits [58] found that CBT is also efficacious for adult anxiety disorders.

Relaxation Techniques

Relaxation techniques can help people develop the ability to cope more effectively with triggers and those causes contributing to anxiety and pain. Common techniques include breathing retraining, progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness meditation, and biofeedback [60].

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Some interventions such as acupuncture, qi-gong, and other modalities of hands imposition, yoga, massage, and hydrotherapy seem to help patients through their action in pain [60] and in anxiety reduction [61].

Spirituality and Religiosity

Several studies have shown the impact of spirituality and religious faiths (S/R) on better mental/physical health, higher quality of life, and lower mortality [62–66]. S/R also seems to play a role on the pain process and influence the treatment of pain. Many authors have shown that persons with chronic pain use religious and spiritual beliefs and activities to cope with pain [67, 68••]. Nevertheless, usually this aspect is under-recognized by therapists [62, 69]. Spirituality and pain were investigated in the following studies.

Harrison et al [70] evaluated 50 patients with sickle cell disease and found that higher church attendance was significantly associated with lower scores on pain measures.

Keefe et al [71] have investigated rheumatoid arthritis patients and found that those with higher religious coping and spirituality had higher levels of positive mood, lower levels of daily negative mood, higher levels of social support, and were less likely to have joint pain.

Lucchetti et al [62] have evaluated older adults from an outpatient rehabilitation setting and found that greater self-reported religiousness was associated with lower ratings of pain.

Büssing et al [72] have studied chronic pain patients and found an association between spirituality/religiosity, positive appraisals, and internal adaptive coping strategies.

Baetz and Bowen [73] have investigated 37,000 individuals from ‘The Canadian Community Health Survey’ and found that religious persons were less likely to have chronic pain and fatigue. Individuals with chronic pain and fatigue were more likely to use prayer and seek spiritual support as a coping method than the general population, and chronic pain and fatigue sufferers who were both religious and spiritual were more likely to have better psychological well-being and use positive coping strategies.

S/R also can have an influence on anxiety. Studies have shown that higher levels of positive S/R are associated with lower levels of anxiety [74, 75] and that multifaith spiritually-based intervention can have positive outcomes for generalized anxiety disorder [76]. Nevertheless, negative religious coping strategies are positively associated with negative psychological adjustment to stress. That is, individuals who reported using negative forms of religious coping experienced more depression, anxiety, and distress [68••, 77]. Therefore, there may be a connection between spirituality, religiosity, anxiety, coping, fear, and pain that could have repercussions on the treatment of chronic conditions and musculoskeletal pain. Further studies are needed on this issue.

Pharmacotherapy

For the treatment of musculoskeletal pain, there are several medications that can be used. Some agents such as simple analgesics (acetaminophen and NSAIDs), muscle relaxants (cyclobenzaprine), and opioids (tramadol) are used in specific contexts [48, 78]. Nevertheless, most intermediate treatment options between simple analgesics and opioids have both analgesic and anti-anxiety effects (antidepressants for example). Here, we will discuss drugs that have both effects (Table 1).

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, start at 10–25, titrate to 100 mg or nortriptyline, start at 10–25, titrate to 100 mg) are drugs that can be used in almost all musculoskeletal pain conditions such as fibromyalgia [79], osteoarthritis, and low back pain [78]. It is also used in anxiety-depression conditions. Nevertheless, some adverse effects such as dry mouth, weight gain, constipation, and morning drowsiness can happen. In addition, physicians must be cautious when prescribing for elderly patients or those with cardiovascular diseases.

Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Duloxetine 60 mg daily and milnacipran 50–100 mg bid are serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) used for musculoskeletal pain that can also treat anxiety symptoms. A placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in patients with depression and moderate-to-severe pain but no organic pain diagnosis found a significant benefit for both pain and depression symptoms [80]. Other drugs such as escitalopram 10–20 mg (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRI]) or venlafaxine 37.5–150 mg (SNRI) are also possible options with lower evidence at this moment. These drugs are usually more tolerable than the tricyclic antidepressants. Other antidepressants may also be included in combination; agomelatine has been studied in anxious patients [81] but not well evaluated in pain.

Anticonvulsants

Other drugs such as pregabalin (300–450 mg daily in divided doses) [82] and gabapentin (1200–2400 mg/d) [83] seem to have positive effects, particularly in fibromyalgia.

Conclusions

There is an intrinsic connection between anxiety, fear, and musculoskeletal pain. Studies have shown that patients with anxiety have higher prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and vice-versa. In this review, we found some similarities in proposed mechanisms and explicative models for both conditions as well as an overlapping between the treatments available. The recognition of this association is important for professionals who deal with chronic pain.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:• Of importance •• Of major importance

Picavet H, Schouten J. Musculoskeletal pain in The Netherlands: prevalences, consequences and risk groups, the DMC3-study. Pain. 2003;102:167–78.

Magni G, Marchetti M, Moreschi C, Merskey H, Luchini SR. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms in the National Health and Nutrition Examination I. Epidemiologic follow-up study. Pain. 1993;53:163–8.

Bergman S, Herrström P, Högström K, Petersson IF, Svensson B, Jacobsson L. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1369–77.

Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25:173–83.

Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull WHO. 2003;81:646–56.

Carnes D, Parsons S, Ashby D, Breen A, Foster N, Pincus T, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain rarely presents in a single body site: results from a UK population study. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1168–70.

Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:23–33.

Andrews G, Hobbs MJ, Borkovec TD, Beesdo K, Craske MG, Heimberg RG, et al. Generalized worry disorder: a review of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:134–47.

Means-Christensen AJ, Roy-Byrne PP, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, Stein MB. Relationships among pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:593–600.

Orenius TI, Koskela T, Koho P, Pohjolainen T, Kautiainen H, Haanpää M, et al. Anxiety and Depression Are Independent Predictors of Quality of Life of Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. J Health Psychol. 2012; [in press].

Karakurum B, Soylu Ö, Karatas M, Giray S, Tan M, Arlier Z, et al. Personality, depression, and anxiety as risk factors for chronic migraine. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114:1391–9.

Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–32.

Gormsen L, Rosenberg R, Bach FW, Jensen TS. Depression, anxiety, health-related quality of life and pain in patients with chronic fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(127):e1–8.

Pesa J, Lage MJ. The medical costs of migraine and comorbid anxiety and depression. Headache. 2004;44:562–70.

James JE, Hardardottir D. Influence of attention focus and trait anxiety on tolerance of acute pain. Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7:149–62.

Olatunji BO, Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS. Is hypochondriasis an anxiety disorder? Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:481–2.

Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Fear and anxiety: divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;84:65–75.

Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I, et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:135–43.

Tchivileva IE, Lim PF, Smith SB, Slade GD, Diatchenko L, McLean SA, et al. Effect of catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism on response to propranolol therapy in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:239–48.

McGrath M, Kawachi I, Ascherio A, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, De Vivo I. Association between catechol-O-methyltransferase and phobic anxiety. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1703–5.

Enoch MA, Xu K, Ferro E, Harris CR, Goldman D. Genetic origins of anxiety in women: a role for a functional catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism. Psychiatr Genet. 2003;13:33–41.

Montag C, Buckholtz JW, Hartmann P, Merz M, Burk C, Hennig J, et al. COMT genetic variation affects fear processing: psychophysiological evidence. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:901–9.

Wolfe F, Russell I, Vipraio G, Ross K, Anderson J. Serotonin levels, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms in the general population. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:555–9.

Gordon JA, Hen R. The serotonergic system and anxiety. Neuro Mol Med. 2004;5:27–40.

Wood PB, Patterson JC, Sunderland JJ, Tainter KH, Glabus MF, Lilien DL. Reduced presynaptic dopamine activity in fibromyalgia syndrome demonstrated with positron emission tomography: a pilot study. J Pain. 2007;8:51–8.

Nikolaus S, Antke C, Beu M, Müller HW. Cortical GABA, striatal dopamine and midbrain serotonin as the key players in compulsive and anxiety disorders--results from in vivo imaging studies. Rev Neurosci. 2010;21:119–39.

Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:169–91.

Finestone HM, Alfeeli A, Fisher WA. Stress-induced physiologic changes as a basis for the biopsychosocial model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a new theory? Clin J Pain. 2008;24:767–75.

Bingefors K, Isacson D. Epidemiology, co-morbidity, and impact on health-related quality of life of self-reported headache and musculoskeletal pain—a gender perspective. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:435–50.

Stoyanova M, Hope DA. Gender, gender roles, and anxiety: perceived confirmability of self report, behavioral avoidance, and physiological reactivity. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:206–14.

Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, Tai KS, Leslie D. The burden of chronic low back pain: clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and healthcare costs in usual care Settings. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;Dec 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Knook LME, Konijnenberg AY, van der Hoeven J, Kimpen JLL, Buitelaar JK, van Engeland H, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents presenting with unexplained chronic pain: what is the prevalence and clinical relevancy? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:39–48.

Asmundson GJG, Carleton RN. Fear of pain is elevated in adults with co-occurring trauma-related stress and social anxiety symptoms. Cogn Behav Ther. 2005;34:248–55.

Greenberg J, Burns JW. Pain anxiety among chronic pain patients: specific phobia or manifestation of anxiety sensitivity? Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:223–40.

• Bair MJ, Wu J, Damush TM, Sutherland JM, Kroenke K. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:890–7. This study showed that the added morbidity of depression and anxiety with chronic pain is strongly associated with more severe pain, greater disability, and poorer quality of life.

Carleton R, Abrams M, Kachur S, Asmundson GJG. Waddell’s symptoms as correlates of vulnerabilities associated with fear–anxiety–avoidance models of pain: pain-related anxiety, catastrophic thinking, perceived disability, and treatment outcome. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:364–74.

Beneciuk JM, Bishop MD, George SZ. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity during a neurodynamic test for the median nerve in healthy participants. Manual Ther. 2010;15:370–5.

Jensen JC, Haahr JP, Frost P, Andersen JH. The significance of health anxiety and somatization in care-seeking for back and upper extremity pain. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;29:86–95.

Rachman S. Anxiety. UK: Psychology Press Ltd, Publishers; 1998.

Cannon WB. Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage. Appleton: Oxford; 1929.

Leeuw M, Goossens MEJB, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JWS. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30:77–94.

Murphy D, Lindsay S, De C, Williams AC. Chronic low back pain: predictions of pain and relationship to anxiety and avoidance. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:231–8.

White TL, Depue RA. Differential association of traits of fear and anxiety with norepinephrine-and dark-induced pupil reactivity. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1999;77:863–77.

Crombez G, Vlaeyen JWS, Heuts PHTG, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80:329–39.

Lethem J, Slade P, Troup J, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21:401–8.

Woolf A, Zeidler H, Haglund U, Carr A, Chaussade S, Cucinotta D, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in Europe: its impact and a comparison of population and medical perceptions of treatment in eight European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:342–7.

Mannerkorpi K, Henriksson C. Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:513–34.

Goldenberg DL. Pharmacological treatment of fibromyalgia and other chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:499–511.

Nardi AE, Lopes FL, Freire RC, Veras AB, Nascimento I, Valença AM, et al. Panic disorder and social anxiety disorder subtypes in a caffeine challenge test. Psychiatry Res. 2009;169:149–53.

Hagen K, Thoresen K, Stovner LJ, Zwart JA. High dietary caffeine consumption is associated with a modest increase in headache prevalence: results from the Head-HUNT Study. J Headache Pain. 2009;10:153–9.

Sawynok J. Caffeine and pain. Pain. 2011;152:726.

Roehrs T, Roth T. Caffeine: Sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:153–62.

Edwards RR, Almeida DM, Klick B, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT. Duration of sleep contributes to next-day pain report in the general population. Pain. 2008;137:202–7.

Bigatti SM, Hernandez AM, Cronan TA, Rand KL. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:961–7.

van Mill JG, Hoogendijk WJG, Vogelzangs N, van Dyck R, Penninx BWJH. Insomnia and sleep duration in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:239–46.

Littlejohn G. Musculoskeletal pain. J Royal Coll Phys Edinburgh. 2005;35:340–4.

Herring MP, O'Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effect of exercise training on anxiety symptoms among patients: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:321–31.

Hofmann SG, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:621–32.

Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1–13.

Hassett AL, Gevirtz RN. Nonpharmacologic treatment for fibromyalgia: patient education, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, and complementary and alternative medicine. Clin Rheum Dis. 2009;35:393–407.

van der Watt G, Laugharne J, Janca A. Complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:37–42.

Lucchetti G, Lucchetti AGL, Badan-Neto AM, Peres PT, Peres MFP, Moreira-Almeida A, et al. Religiousness affects mental health, pain and quality of life in older people in an outpatient rehabilitation setting. J Rehab Med. 2011;43:316–22.

Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: linkages to physical health. Am Psychol. 2003;58:36–52.

Lucchetti G, Lucchetti ALG, Koenig HG. Impact of Spirituality/Religiosity on Mortality: Comparison With Other Health Interventions. Explore. 2011;7:234–8.

Koenig HG. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review. Can Psychiatr Assoc J. 2009;54:283–91.

Lucchetti G, Almeida LGC, Lucchetti ALG. Religiousness, mental health, and quality of life in Brazilian dialysis patients. Hemodialysis Int. 2012;16:89–94.

Rippentrop AE. A review of the role of religion and spirituality in chronic pain populations. Rehabil Psychol. 2005;50:278–84.

•• Peres MFP, Lucchetti G. Coping strategies in chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Reps. 2010;14:331–8. This is a comprehensive review dealing with coping in chronic pain.

Mariotti L, Lucchetti G, Dantas M, Banin V, Fumelli F, Padula N. Spirituality and medicine: views and opinions of teachers in a Brazilian medical school. Med Teach. 2011;33:339–40.

Harrison MO, Edwards CL, Koenig HG, Bosworth HB, Decastro L, Wood M. Religiosity/spirituality and pain in patients with sickle cell disease. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:250–7.

Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Lefebvre J, Underwood L, Caldwell DS, Drew J, et al. Living with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of daily spirituality and daily religious and spiritual coping. J Pain. 2001;2:101–10.

Büssing A, Michalsen A, Balzat HJ, Grünther RA, Ostermann T, Neugebauer EAM, et al. Are spirituality and religiosity resources for patients with chronic pain conditions? Pain Med. 2009;10:327–39.

Baetz M, Bowen R. Chronic pain and fatigue: associations with religion and spirituality. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:383–8.

Shreve-Neiger AK, Edelstein BA. Religion and anxiety: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:379–97.

Braghetta CC, Lucchetti G, Leão FC, Vallada C, Vallada H, Cordeiro Q. Ethical and legal aspects of religious assistance in psychiatric hospitals. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica. 2011;38:189–93.

Koszycki D, Raab K, Aldosary F, Bradwejn J. A multifaith spiritually based intervention for generalized anxiety disorder: a pilot randomized trial. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:430–41.

Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:461–80.

Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:206–19.

Arnold LM, Keck PE, Welge JA. Antidepressant treatment of fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:104–13.

Brecht S, Courtecuisse C, Debieuvre C, Croenlein J, Desaiah D, Raskin J, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of pain in patients with major depressive disorder and at least moderate pain of unknown etiology: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1707–16.

Stein DJ, Ahokas AA, De Bodinat C. Efficacy of agomelatine in generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:561–6.

Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1264–73.

Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Stanford SB, Lalonde JK, Sandhu H, Keck Jr PE, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1336–44.

Disclosures

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lucchetti, G., Oliveira, A.B., Mercante, J.P.P. et al. Anxiety and Fear-Avoidance in Musculoskeletal Pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 16, 399–406 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-012-0286-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-012-0286-7