Abstract

The hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) are a heterogeneous group of disorders defined as persistent and marked blood eosinophilia of unknown origin with systemic organ involvement. HES is a potentially severe multisystem disease associated with considerable morbidity. Skin involvement and cutaneous findings frequently can be seen in those patients. Skin symptoms consist of angioedema; unusual urticarial lesions; and eczematous, therapy-resistant, pruriginous papules and nodules. They may be the only obvious clinical symptoms. Cutaneous features can give an important hint to the diagnosis of this rare and often severe illness. Based on advances in molecular and genetic diagnostic techniques and on increasing experience with characteristic clinical features and prognostic markers, therapy has changed radically. Current therapies include corticosteroids, hydroxyurea, interferon-α, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate, and (in progress) the monoclonal anti–interleukin-5 antibodies. This article provides an overview of current concepts of disease classification, different skin findings, and therapy for HES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

History and Definition

Reports of unexplained hypereosinophilia have been described for decades [1–8] with conditions named Loeffler’s syndrome, Loeffler’s fibroblastic endocarditis with eosinophilia, and eosinophilic leukemia. The terms of hypereosinophilic diseases varied, based on the different organs involved [2, 9]. In 1968, Hardy and Anderson [2] used the term hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) to describe a group of conditions characterized by marked, chronic eosinophilia and multiple organ involvement, including the skin. Chusid et al. [9] analyzed 14 cases of HES among their own patients and 57 cases reported in the earlier literature—reported as cases of eosinophilic leukemia, disseminated eosinophilic collagen disease, or Loeffler’s fibroblastic endocarditis with eosinophilia—and described the first defining features, which formed the basis of the definition of HES: 1) persistent eosinophilia of greater than 1,500 eosinophils/mm3 for longer than 6 months; 2) no other evident cause of eosinophilia, including allergic diseases and parasitic infections; and 3) signs or symptoms of organ involvement by eosinophilic infiltration.

At that point in time, the 6-month duration helped to exclude short-term episodes of eosinophilia such as adverse reactions to medications. However, with advances in understanding of HES and the availability of novel therapeutic agents, the criteria established by Chusid et al. [9] in 1975 became increasingly problematic [8, 10–12]. First, a patient with symptomatic HES should not remain untreated for 6 months [8, 12]. Therefore, it has been suggested recently that patients may be diagnosed without waiting 6 months if they meet the other criteria and their clinical course appears to be chronic and unremitting [8, 12, 13]. Second, in the definition of Chusid et al. [9], the accepted threshold for blood eosinophilia (>1,500 eosinophils/mm3) excluded patients with tissue eosinophilia unaccompanied by marked blood eosinophilia. Additionally, the subgroups of HES with identification of several well-characterized disease entities, such as Fip1-like-1–associated HES, would no longer fit into the original definition of HES, as the cause of eosinophilia is identified. Subsequently, a new working definition that overcomes the limitations with the original definition was suggested by Simon and coworkers (Table 1) [12]. All patients with blood eosinophilia (>1,500 eosinophils/mm3) without a secondary cause of eosinophilia (allergic diseases, allergic drug reactions, parasitic helminth infections, HIV infection, solid tumors) should be considered to have HES or a disorder that overlaps with the definitions of HES, regardless of the number and nature of affected organs or potential pathogenic mechanisms [12].

The second original criterion of Chusid et al. [9]—to rule out all other known causes of eosinophilia—remains an important issue in hypereosinophilic patients. Mild hypereosinophilia (<1,000/μL) is a common biological finding and can be ascribed to an underlying disease in most cases (e.g., atopic eczema) [14, 15]. In addition, several more or less frequently encountered diseases have to be excluded in patients with marked hypereosinophilia by etiologic work-up; diseases such as parasitic diseases involving tissue-invasive helminths, atopy, allergic drug reactions, solid tumors, connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, and infectious diseases (e.g., HIV) must be ruled out as a secondary cause of eosinophilia.

Subtypes of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (Pathogenesis-Driven Classifications of Hypereosinophilic Syndrome)

The clinical heterogeneity of HES has long been recognized; however, in the past two decades, techniques have become available to identify subtypes of HES with different underlying etiologies. The two best-described subtypes are the lymphocytic variant HES (L-HES), in which the underlying cause of eosinophilia is an increased secretion of eosinophilopoietic cytokines by T lymphocytes [13, 16–20], and myeloproliferative HES (M-HES), most commonly due to an interstitial deletion in chromosome 4 [21–23] leading to stem cell mutations, with expression of the PDGFRA fusion genes with constitutive tyrosine kinase activity. These subtypes are associated with differences in clinical presentation, prognosis, and response to therapy [13, 23].

Myeloproliferative Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

The myeloproliferative variant is the more aggressive form of HES that is associated with features of myeloproliferative disorders [13, 22–25]. Notably, the discovery of underlying chromosomal events followed the observation that four of five HES patients responded well to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate [21, 26].

M-HES is characterized by chromosomal events, particularly a fusion event that activates the tyrosine kinase platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA). PDGFRA is a unique fusion protein with an interstitial deletion in chromosome 4 (del[4q12]), which results in the formation of a fusion gene between an uncharacterized gene, Fip1-like 1 (FIPL1), and the PDGFRA gene (FIP1L1–PDGFRA). The World Health Organization has classified this form of HES as chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL). This classification system has utility when a clonal or neoplastic process is clearly defined. However, in the majority of patients with HES, the separation of patients with molecularly defined myeloproliferative disease from those with similar clinical features but no identifiable mutation is problematic [27]. Also, there is considerable overlap between myeloproliferative forms of HES and CEL.

Many patients with detectable FIP1LI–PDGFRA fusion genes fulfill the current World Health Organization criteria for CEL [28]. However, not all patients with myeloproliferative features of HES can currently be characterized at the molecular level.

Characteristic clinical features of the M-HES variant, which predominantly affects males, consist of the presence of the FIPL1–PDGFRA fusion gene mutation, dysplastic eosinophils on peripheral smear, elevated serum vitamin B12, elevated serum tryptase levels, anemia or thrombocytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, increased bone marrow cellularity, atypical/spindle-shaped mast cells in bone marrow, myelofibrosis, endomyocardial damage, cardiac intramural thrombi, endomyocardial fibrosis, and normally good response to imatinib therapy.

Klion and colleagues [23] suggested in consensus with the hypereosinophilic syndromes working group (meeting in conjunction with the International Eosinophil Society) that patients with the absence of detectable FIPL1–PDGFRA, related chromosomal mutation, or other evidence of eosinophil clonality could be considered to fall under M-HES if four or more of the following eight features are present:

-

1.

Presence of dysplastic eosinophils on peripheral blood smear

-

2.

Serum B12 level greater than 1,000 pg/mL

-

3.

Serum tryptase greater than or equal to 12 ng/mL

-

4.

Anemia or thrombocytopenia

-

5.

Hepatosplenomegaly

-

6.

Bone marrow biopsy cellularity greater than 80%

-

7.

Presence of dysplastic mast cells in the bone marrow (>25% being spindle shaped [22])

-

8.

Myelofibrosis (presence of antireticulin antibody staining on bone marrow biopsy [22]).

Notably, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate is the treatment of choice for patients who have high tyrosine kinase activity of PDGFRA.

Concerning cutaneous symptoms in M-HES, mucosal ulcerations have been reported, and the prognosis of the patients presenting with mucosal ulcerations was poor [29–31]. Further cases of mucosal ulcerations in patients categorized as M-HES with tissue fibroses were described [22]. Notably, cases of mucosal ulcerations in HES patients have been initially diagnosed as Behcet’s syndrome [31]. Further rare cutaneous symptoms are splinter hemorrhages and/or nail-fold infarcts, which may be initial clues to thromboembolic complications [31]. Urticaria and angioedema may occur but are characteristic of other HES subtypes.

Lymphocytic Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

The other main subtype is L-HES, in which activated T lymphocytes, the so-called T-helper type 2 (Th2) cells, produce a variety of hematopoietic cytokines, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin (IL)-3, and IL-5. The ability of these T cells to produce IL-5 accounts for hypereosinophilia, as eosinophil development from hematopoietic progenitors is regulated mainly by IL-5, which has a selective role in eosinophil maturation, differentiation, mobilization, activation, and survival [19, 32–34]. The first reported case with clear features of L-HES was that of a patient with high serum IgE and IgM levels as well as cutaneous, pulmonary, and vascular involvement. Investigation of this patient’s T cells revealed a phenotypically abnormal subset of CD3−CD4+ T cells producing abnormal amounts of IL-4 and IL-5 in vitro [35]. Subsequently, more cases with populations of abnormal, activated T cells with an abnormal immunophenotype were reported [19, 20, 36–38]. In most of these cases, clonality was demonstrated. Another important observation was the development of T-cell lymphoma in HES patients with clonal CD3−CD4+ T cells [19].

Immunophenotyping of peripheral lymphocytes of affected patients revealed signs of increased activation of peripheral T cells with increased expression of the activation markers CD25 and HLA-DR on CD4+ cells. Abnormal or clonal T-cell populations could be detected by lymphocyte phenotyping and analysis of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement patterns using both Southern blot and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification in search of T-cell clonality. Frequent CD3−CD4+ expression and less frequent CD3+CD4−CD8− expression were described, and the abnormal T-cell population expressed activation markers (CD25 or HLA-DR +), but not CD7 or CD27 [13, 16, 19, 20, 36, 37, 39]. Finally, enhanced production of type 2 cytokines, such as IL-5 or IL-4, was measured in supernatants of patients’ peripheral blood mononuclear cells [19, 20]. Characteristic clinical features of the lymphocytic variants, which affect males and females equally, consist of absence of detectable FIPL1–PDGFRA fusion gene and frequent skin involvement [13, 16–18, 37, 40]. In accordance with the type 2 cytokine profile, serum IgE levels are often increased and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia may be observed (increased serum IgM and/or IgG levels). Other complications occur more frequently in the lungs and the digestive system, with a few patients developing endomyocardial fibrosis.

In L-HES, frequently increased serum levels of an eosinophil granule protein, the so-called eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) [20, 41, 42] and the eosinophil-derived neurotoxin [32], as well as increased serum levels of IL-5 have been detected. Furthermore, serum levels of a chemokine for eosinophils—the so-called thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC), a product of activated Th2 cells—were increased [20, 32, 43].

Patients with the lymphocytic variant of the disease rarely have cardiac but often exhibit cutaneous involvement with polymorphous skin symptoms, as reported below, and generally show a good response to glucocorticosteroids. It has also been described that the lymphocytic forms of HES clearly overlap with T-cell malignancies, including lymphoma, predominantly in those patients with a demonstrable clonal T-cell population. Some patients with clonal T-cell populations and hypereosinophilia developed cytogenetic abnormalities and clinical evidence of lymphoma over time [16, 19, 37, 44–47].

Undefined Category, Overlap Category, and Associated Category

Many patients do not adequately meet the features of M-HES or L-HES and fall under the “undefined” category [23]. Because of the heterogeneous nature of the disease, comprising a number of subtypes, it is not surprising that the clinical features can vary considerably from patient to patient. In 2005, the hypereosinophilia working group (meeting in conjunction with the International Eosinophil Society [23]) designed a classification algorithm intended to capture all these diseases associated with significant and prolonged peripheral blood hypereosinophilia. Besides the myeloproliferative or lymphocytic variants, in this classification, the overlap category includes patients who do not accurately fulfill the criteria for HES (but have an apparent restriction of tissue-specific eosinophilia to specific organs) and includes eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroenteritis, eosinophilic pneumonia, and eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome [23, 48]. Many of the syndromes with hypereosinophilia and restriction to the skin, which are mentioned below, may be included in the overlap category.

The associated category includes cases of eosinophilia with other diagnoses, such as Churg-Strauss syndrome, systemic mastocytosis, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, and HIV infection. The undefined category includes cases of unexplained eosinophilia that do not meet the three key criteria of HES and do not meet the other miscellaneous categories described.

Features in Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

Common Features

The National Institutes of Health case series reported that fatigue is present in 26% of patients, and fever in 12% [45]. Other presenting symptoms include cough, breathlessness, and muscle pains [4, 8, 10, 49]. Further features are stomach pain, diarrhea, and weight gain due to edematous swelling of the arms and legs.

Peripheral eosinophils are generally mature, but eosinophilic myeloid precursors occasionally can be seen in the peripheral blood [3, 8]. Other hematologic laboratory values can also be abnormal, depending on the subtype [8]. Any cytogenetic or molecular evidence of eosinophil clonality indicates a diagnosis of CEL, and, as discussed later, some cases of M-HES are actually CEL [8, 28].

Splenomegaly can be seen in HES, and hypersplenism may be painful and may lead to anemia and thrombocytopenia [3, 4, 8]. The presence of lymphadenopathy has been observed in HES, and enlarged lymph nodes have been reported in patients who developed lymphoma [45–47]. Bone marrow biopsy often shows increased eosinophils and eosinophil precursors. Standard cytogenetic analysis is normal in most patients [49].

Cutaneous Features

Affected patients may first present with symptoms related to their particular organ involvement; therefore, special attention must be given to skin symptoms, as they can easily be recognized and may be the predominant presenting sign in L-HES and the undefined category. Cutaneous signs in a patient with hypereosinophilia may be the initial clue to an HES variant. Cutaneous symptoms predominantly occur in cases of L-HES. In cases of skin symptoms, biopsies of affected skin lesions can easily be obtained (in contrast to other organs possibly involved), and the presence of numerous eosinophils in the affected skin of a patient with hypereosinophilia may draw attention to this potentially life-threatening disease.

Clinical presentations of cutaneous symptoms in HES are notoriously variable and unpredictable. Various patterns of skin involvement can occur with HES. Parillo et al. [50] reported in 1978 about polymorphous skin involvement in more than 60% of cases diagnosed as HES. Cutaneous symptoms consisted of pruritus, chronic and intermittent urticaria, episodic angioedema, scaly erythema, papules, pruriginous nodules, bullous lesions, petechiae with vasculitis, and leukemoid infiltrations [17, 19, 29–31]. In the original analyses of Chusid et al. [9] and Kazmierowski et al. [51], the most frequent dermatologic abnormalities were erythematous, pruritic maculopapules; urticaria; and angioedema of the face. Moreover, HES patients may present with erythema anulare centrifugum [52, 53], necrotizing vasculitis [54, 55], livedo reticularis, and purpuric papules [55]. In many cases, association with Wells’ syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis) has been reported [56–58].

In nearly all reported L-HES patients, different patterns of cutaneous involvement have been seen, which may include eczematous dermatitis, nonspecific erythroderma, pruritus, urticaria, and angioedema [7, 17, 19, 20, 37]. Skin biopsies of specific lesions, which should be performed before onset of treatment, typically show a lymphocytic inflammatory pattern with increased eosinophil granulocytes in the affected tissue [13, 20]. The inflammatory infiltrate may be superficial in some cases, whereas in others, it extends into the subcutaneous fat. The inflammatory infiltrate may also be perivascular as well as interstitial. Skin biopsies of unaffected areas, as well as biopsies taken after onset of efficient therapy, often do not reveal numerous eosinophils.

HES-related cutaneous features are regarded to be a frequent finding in L-HES; otherwise they may be observed in M-HES or other HES variants or related diseases as well [16, 29–31]. Clearly, there is a considerable overlap between L-HES and skin-restricted eosinophilic disorders. Many patients with skin symptoms and hypereosinophilia, including those with detectable T-cell abnormalities or even detectable clonal T-cell populations, fulfill the current criteria for L-HES. On the other hand, not all patients with skin symptoms can currently be characterized at the molecular level, as diagnosis is limited and proof is difficult to obtain, even in research laboratories with considerable expertise. Notably, single patients with skin symptoms and demonstrable clonal T-cell populations in fact developed clinical evidence of lymphoma over time [16, 19, 44, 46, 47].

Angioedema

One pattern involves a predominance of angioedema combined with urticarial lesions, which traditionally have been thought to be associated with a good response to steroids and a more benign course of HES [49]. Bilateral periorbital swelling, sometimes with delicate hyperpigmentations, may be observed (Fig. 1).

Angioedema in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome affecting the skin and internal organs (polyserositis with dense eosinophilic ascites and pleural effusions, liver affection). Patient developed slight periorbital pigmentation. Besides angioedema, the patient had edematous swelling of the extremities and urticarial lesions resembling eosinophil cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome). For 8 years, this patient was diagnosed as having Quincke’s edema and chronic intermittent urticaria

If eosinophilia is associated with episodic angioedema without proof of further organ involvement, the possible diagnosis of episodic angioedema with eosinophilia syndrome or Gleich’s syndrome should be considered, which is described a separate entity. Gleich’s syndrome is characterized by recurrent episodes of angioedema, urticaria, pruritus, fever, weight gain, elevated serum IgM, oliguria, and leukocytosis with peripheral blood eosinophilia [7, 59, 60]. Some patients presenting with Gleich’s syndrome (mentioned below) may, however, have underlying L-HES.

Eosinophils may induce cutaneous edema through the release of their toxic granule proteins, such as ECP, eosinophil peroxidase, and major basic protein [61, 62]. These granule proteins were shown to elicit a wheal-and-flare reaction in human skin [61].

Urticarial Lesions

Patients may develop urticarial lesions that do not differ from common urticaria. Urticarial lesions may begin with prodromal burning or itching, followed by redness and swelling, resolving, and reoccurrence in different locations. On the other hand, lesions may differ from common urticaria and consist of unusual cutaneous erythematous swelling resembling bacterial cellulitis (Figs. 2 and 3) and the so-called Wells’ syndrome (mentioned below). The urticarial lesions may evolve into large areas of erythematous edema within a few days. Individual lesions may persist for days to weeks—and therefore differ from common urticaria—and gradually change from bright red to brown red to blue gray, resembling the color of morphea lesions, a phenomenon that has already been described in eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) [62]. In fact, Wells’ syndrome in association with urticarial lesions and HES has been described [42, 56].

Urticarial lesion in hypereosinophilic syndrome, with cutaneous erythematous swelling resembling bacterial cellulitis. Lesions may evolve in a few days into large areas of erythematous edema. Individual lesions persist for days to weeks (and therefore differ from common urticaria) and gradually change color from bright red to brown red and finally to blue gray

In acute lesions, numerous eosinophils and eosinophilic debris may be detected, as well as eosinophils in the interstitial and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. As lesions resolve, eosinophils become less prominent. Notably, antihistamines often are found to be ineffective in urticarial lesions in HES [62].

Pruriginous Papules and Papulonecrotic Lesions

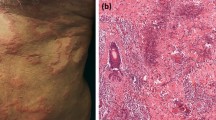

A further pattern of the cutaneous involvement of HES consists of erythematous pruritic papules and nodules (Fig. 4) with a nonvasculitic, mixed cellular, and dermal infiltrate [3, 4, 31, 51]. These common patterns of cutaneous involvement are reported to be more prevalent in L-HES variants. The pruritus in these patients tends to be almost intolerable.

Erythematous pruritic papules and nodules (a) partially centrally ulcerated in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome (b). Hematoxylin-eosin–stained biopsy tissues demonstrating inflammatory cell infiltrates largely consisting of eosinophils and lymphocytes (c). On the right hand, larger magnification of perivascular infiltrate with numerous eosinophils is presented (d)

In these patients, different types of skin lesions tend to appear. Type one consists of pruritic, hyperemic papules ranging from pinhead to mole size. The second type consists of mole-sized urticarial eruptions that can conflate to palm-sized plaques. In the course of disease, the skin may be thickened and become pachydermic, as it has been described for patients with pachydermatous eosinophilic dermatitis [63].

Biopsy of skin lesions shows predominantly perivascular infiltration composed of mainly eosinophilic and lymphoid cells with numerous eosinophils. In some cases, the infiltrate is superficial, whereas in others, it extends into the subcutaneous fat. Patients may have axillary and inguinal lymphadenopathy (dermopathic lymphadenopathy).

Pruriginous papules and papulonecrotic lesions can occur in any combination as part of HES but were also considered as separate entities from HES if they occurred in isolation without meeting the original criteria for HES. However, most of these patients show features of the lymphocytic variant of the disease with elevated IgE levels and TARC levels as well as abnormal T-cell populations [20]. Continued follow-up of these cases will delineate whether T-cell lymphoma will develop in these patients.

In those patients, in our experience, therapy is extremely difficult. Orally or intravenously administered antihistamines have no effect on the intense and severe pruritus. Often even systemic prednisolone may not improve pruritus or blood eosinophilia. Dapsone has been used successfully in some patients with this type of skin involvement and may be administered in a prednisolone–dapsone combination. Successful treatment with consecutive reduction of blood and tissue eosinophils, as well as serum IL-5, eotaxin, and TARC levels following therapy with anti–IL-5 antibodies has been reported [20].

Eczematous Lesions

Eczematous lesions may occur anywhere on the trunk and usually present as persistent, thin, erythematous, and scaling plaques. Lesions may resemble atopic eczema (Fig. 5) or eczematous lesions observed in precursor lesions of mycosis fungoides. They may appear in any location and may evolve into erythroderma, which is usually macular and scaling. With progression of the disease, adenopathy may be noted in the axillae and the groin.

Pruritus may be severe. Eczematous lesions may go along with swelling and a feeling of tenseness in the limbs. In all our observed cases [20, 39, 64], patients had no personal or family history of atopy. However, serum IgE and serum ECP levels were found to be elevated, and patients were FIPL1–PDGFRA negative. Investigation of patients’ T cells revealed abnormal T-cell subpopulations in many cases; however, no direct evidence for clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement and no histopathological evidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be obtained. In the course of disease, patients may develop other cutaneous features, such as pruriginous papules (Fig. 4), urticarial lesions, angioedema, or edematous swelling of acres (Fig. 6) or extremities.

Skin biopsies reveal acanthosis as well as inflammatory perivascular and interstitial cell infiltrates consisting of numerous eosinophils and lymphocytes in the acute stage of the disease (Fig. 7). The infiltrate may be superficial or may extend to the subcutis. After therapy, fewer eosinophils may be detected.

Patients with eczematous lesions usually respond well to different therapies. In mild cases, topical steroids, photochemotherapy (psoralen + UVA, or PUVA therapy) [64] or UVA1 therapy may be effective in improving the skin lesions [65]. Successful treatment with consecutive reduction of blood and tissue eosinophils as well as serum IL-5, eotaxin, and TARC levels following therapy with anti–IL-5 antibodies has been reported [20].

Clonal populations of abnormal T cells producing IL-5 occur in some patients with eosinophilia, and it is unclear whether they represent a premalignant lymphoproliferative disorder. In a patient presenting with eosinophilia and eczematous lesions and phenotypically aberrant T cells, T-cell lymphoma was ultimately diagnosed [19]. These findings may be coincidental but also support the idea that abnormal T cells in patients with persistent eosinophilia can be precursors of malignant T cells.

Mucosal Ulcers

A less commonly reported pattern of mucocutaneous involvement is that of debilitating mucosal ulcers that can affect multiple mucosal areas of the body [30, 31]. Successful treatment of HES in association with mucocutaneous ulcers was described by Butterfield and Gleich [66] in 1994. These ulcers are reported to interfere with adequate hygiene and nutrition and indicate a subset of HES patients with poor prognosis due to vascular events or infection [30, 31]. The prognosis for this subset of patients remained poor [29–31] until response to imatinib mesylate had been reported [26]. Notably, in patients with HES, initial diagnosis of Behcet’s syndrome was based on severe, chronic, recurrent oral and genital ulcers [29, 30]. Subsequently, association of mucosal ulcers in patients categorized as having M-HES with tissue fibrosis was found [22].

Splinter Hemorrhages

Splinter hemorrhages and/or nail-fold infarcts may predict thromboembolic complications with eosinophilic endomyocardial involvement; therefore, special attention must be devoted to this rare finding in hypereosinophilic patients [31].

Organ Involvement Other than Skin

Heart

Cardiac involvement can occur in HES [3, 4, 9, 67, 68] and is a cause for concern, as involvement of the heart, at least in the past, was often associated with high morbidity and mortality [3, 4, 9]. Increased frequency of cardiac involvement in FIP1L1–PDGFRA–positive patients is reported [22]. Improvement of cardiac findings with imatinib therapy has been described [69].

Nervous System

Three neurological complications can occur in HES [70–72]: 1) primary generalized central nervous system dysfunction, 2) peripheral neuropathies, and 3) thromboembolic phenomena affecting the central nervous system [8, 70]. It has been hypothesized that 1) specific eosinophil granule proteins, such as eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, may cause direct nerve damage; or that 2) eosinophil-mediated damage to endothelial cells leads to edema that subsequently causes pressure on nerves and, consequently, axonal damage [8, 71].

Lungs

Lung involvement can occur in patients with features of M-HES as well as L-HES at variable intensity. The most common feature is a chronic, nonproductive cough with a normal chest radiograph [4, 8]. Pleural effusions may occur [73]. Pulmonary fibrosis has been shown to develop over time [49].

Gastrointestinal Tract

Gastrointestinal involvement with eosinophilic esophagitis, gastritis, enteritis, or colitis can occur in any combination as part of HES [8, 72, 74–78].

Eyes

Ocular involvement may present as blurry vision and may be caused by microembolic phenomena or local microthrombi [49, 79, 80]. There are reports of frequent choroidal abnormalities in HES patients [79].

Skeletal System

In some cases, arthralgias, arthritis, effusions of the large joints, and Raynaud’s phenomenon have been observed, and digital necrosis can also occur [81]. Myalgias can occur in HES along with other systemic symptoms [6]; focal myositis and polymyositis, however, are rare [82, 83].

Recent Developments

During the past 30 years, several clinical features were identified that seemed to predict a worse prognosis in HES, including high eosinophil count exceeding 100,000/μL, hepatosplenomegaly, the presence of chromosomal abnormalities or circulating immature precursor cells, increased serum vitamin B12, elevated leukocyte alkaline phosphatase, anemia, and thrombocytopenia [8, 9, 84, 85]. These myeloproliferative features were known for decades, and in 2003, molecular evidence of a myeloproliferative variant was detected with the discovery of an interstitial deletion on chromosome 4q12 that leads to fusion of the FIP1L1 and PDGFRA genes [8], with the fusion product encoding for a protein that has significant constitutive tyrosine kinase activity [21]. The presence of this fusion protein was found to be responsible for pronounced eosinophilia in the affected patients [8]. Patients who have this fusion mutation are now known to form the majority of the so-called M-HES variants [8, 13]. Consequently, it was found that most patients who had the fusion mutation showed good clinical response when treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib [13, 17, 18, 22]. However, some patients showed good clinical response to treatment with imatinib but did not have a detectable FIP1L1–PDGFRA mutation. Possibly, these patients may have other, not-yet-defined mutations leading to similar mutant proteins with tyrosine kinase activity [13, 21]. On the other hand, patients with symptoms of M-HES have been described who did not respond to imatinib therapy. It is thought that these patients have imatinib-resistant mutant proteins with tyrosine kinase activity or that the eosinophilia is caused by other molecular mechanisms [13].

However, in a large proportion of affected patients, no FIP1L1–PDGFRA mutation could be detected. Furthermore, the association with increased IgE levels in some patients pointed to the possibility that T cells could be involved in disease pathogenesis. Another study from HES patients found that T-cell clones from patients’ peripheral blood displayed eosinophilopoietic activity [19]. This finding led to the idea that an abnormal T-cell population might be the driving factor, with recruitment of eosinophils being a secondary process, and that some HES cases may be driven by a Th2 process [35–37, 86]. Since 1994, patients with clonal T-cell populations with aberrant immunophenotype who secreted Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 have been described [17, 35–37, 40, 86]. The pathogenic T cells generally displayed an aberrant immunophenotype, and the CD3-CD4+ cells represent the most frequently encountered subset, but further aberrant T-cell surface markers such as the CD3+CD4−CD8− phenotype also have been described. The ability of these T cells to produce IL-5 accounts for hypereosinophilia, as eosinophil development from hematopoietic progenitors is regulated mainly by IL-5, which has a selective role in eosinophil maturation, differentiation, mobilization, activation, and survival [32, 33]. Patients with clonal T-cell populations with an aberrant immunophenotype were identified (by flow cytometry or reverse transcriptase PCR for T-cell receptor usage) to produce increased IL-5 in idiopathic hypereosinophilia.

Consecutively, patients with a proven overproduction of Th2 cytokines were subsequently diagnosed as having L-HES subtypes [18, 43]. In L-HES patients, increased levels of TARC—a product of activated Th2 cells—were found in serum as well as other mediators, such as IL-5, eotaxin (another important eosinophil chemokine), and the toxic granule proteins ECP and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin [20, 32]. It has been suggested recently that detection of high serum TARC levels may be indicative of T-cell–driven hypereosinophilia and should prompt careful T-cell phenotyping and PCR analysis of T-cell receptor gene rearrangements [40] as well as investigation for T-cell lymphoma.

In consequence, subsequent studies showed that mepolizumab, an IL-5 monoclonal antibody, lowered blood eosinophil levels and improved the patients’ condition with tolerance [20, 32, 87]. Also, mediators such as eosinophil granule proteins and serum TARC levels declined following therapy with a recombinant anti–IL-5 antibody [20, 32].

Concerning the proportion of patients who fall into the subtypes, a French study found 31% with L-HES and 17% with FIPL1–PDGFRA, and a British study found 11% with the FIPL1–PDGFRA M-HES variant [88]. Due to varying expertise (e.g., hematology, dermatology, allergy), the frequency of L-HES and M-HES cannot be measured precisely, but recent studies do indicate that the prevalence of FIPL1–PDGFRA–positive patients is 10% [88], and the prevalence of patients with clonal/abnormal populations of T cells detected by PCR or flow cytometry is likely between 17% and 26% [89]. Many of the patients with HES remain in the undefined subtype and need to be carefully observed and monitored to prevent uncontrolled eosinophilia and subsequent organ damage.

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome–Associated Syndromes (Skin-Restricted Eosinophilic Disorders)

Associated syndromes may be distinguished partly by characteristic histopathology and do not extend beyond the respective target organ; hence, multiple organ involvement is typical of HES. Many cases of the syndromes mentioned below do not have the tendency to develop further organ damage, for reasons yet unknown. The distinct eosinophilic syndromes below were separated from HES in the past. Nevertheless, individual patients may occasionally present with overlapping features, and a new definition would include them as organ-specific variants of HES.

Cutaneous findings can occur in any combination as part of HES. Skin involvements had been considered separate entities from HES if they occurred in isolation without meeting the criteria for HES. There are several syndromes associated with hypereosinophilia featuring skin involvement with numerous eosinophils in affected skin lesions proven by skin biopsy, but a lack of association with internal organ involvement. However, some of these patients present with a clinical profile indistinguishable from the lymphocytic variant of the disease, with elevated TARC levels, elevated IgE levels, elevated serum IL-5, and signs of activation of peripheral T cells. However, proof of internal organ involvement may be difficult to establish, and further organ symptoms may develop over time.

Gleich’s Syndrome

Episodic angioedema with eosinophilia is characterized by recurring episodes of angioedema, urticaria, fever, high serum IgE levels, and lack of association with cardiac damage (Gleich’s syndrome) [7]. Among patients with the lymphocytic variant of the disease, some present with a clinical profile indistinguishable from that encountered in Gleich’s syndrome. A syndrome similar to Gleich’s syndrome is characterized by nonepisodic angioedema with eosinophilia and is seen predominantly in younger women [60, 90]. This nonepisodic angioedema with eosinophilia syndrome is distinct from HES in that it usually consists of a single self-limited attack [90].

Wells’ Syndrome

Urticarial lesions and bacterial cellulitis-like skin lesions may also be seen in another related syndrome, the so-called Wells’ syndrome. The syndrome consists of chronically recurring eosinophilic cellulitis that occurs with blood and bone marrow eosinophilia as well as (though rarely) facial nerve paralysis, arthralgias, and myalgias [31, 62, 91, 92]. However, in some cases, especially in cases combined with further organ involvement other than the skin, Wells’ syndrome may be considered as cutaneous manifestations of HES [56, 64].

Histopathologic changes vary in this syndrome. In acute lesions, so-called “flame figures,” which are masses of eosinophils and eosinophilic debris surrounding amorphous collagen fibers, are prominent. As lesions resolve, eosinophils become less prominent [62]. The histologic pattern of flame figures may also be seen in other disease processes combined with eosinophilic infiltration of the skin [62], including pemphigoid, prurigo, eczema, insect bites, as well as parasitic and dermatophyte infestations. Peters and colleagues [93] examined lesions in Wells’ syndrome for the presence of eosinophil granule protein and showed extensive extracellular deposits in the skin. Deposits of toxic eosinophil granule proteins suggest that eosinophil degranulation is an important process in mediating tissue damage in this disease [93, 94].

Hypereosinophilic Dermatitis

In 1981, Nir and Westfried [95] described a generalized polymorphous skin eruption associated with marked blood and skin tissue eosinophilia. They used the term hypereosinophilic dermatitis and considered it a distinct entity within the spectrum of hypereosinophilic diseases. Similar rare cases subsequently have been reported [96]. A variant of this disorder has been observed in three South African girls and designated pachydermatous eosinophilic dermatitis [63]. These patients exhibited hypertrophic genital lesions, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and an eosinophil-rich lymphohistiocytic cutaneous infiltrate. It is notable that in these patients, elevation of lactic dehydrogenase level was described [63]—a feature that was found in all our patients presenting with skin lesion and HES.

NERDS Syndrome

NERDS (nodules-eosinophilia-rheumatism-dermatitis-swelling) syndrome, a similar feature, was described in 1993 by Butterfield et al. [97]. This consisted of nodules (large, nontender, arising from the tenosynovium of extensor tendons), marked peripheral blood eosinophilia, rheumatism, episodic swelling of the hands and/or feet, and pain in the adjacent muscles and joints. The originally described patients had chronic pruritic dermatitis with prominent lichenification and, based on their clinical course, revealed a distinctive, relatively benign eosinophilic disorder with good long-term prognosis [97].

Associated Diseases or Syndromes and Differential Diagnosis

Mastocytosis

The differential diagnosis of HES involves mastocytosis. Patients with mastocytosis present with elevated serum tryptase levels and often have increased numbers of atypical mast cells in the bone marrow. Although HES and mastocytosis can overlap, HES patients can be distinguished by the absence of somatic c-kit mutations that can be seen in mastocytosis [22]. It is notable that patients with mastocytosis, in which the most common c-kit mutation is the D816V mutation, do not respond to imatinib therapy [28, 98].

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

A major vasculitis that is associated with eosinophilia is Churg-Strauss syndrome. A history of asthma, nonfixed pulmonary infiltrates, eosinophilia, paranasal sinus abnormalities, mononeuropathy of polyneuropathy, and biopsies showing necrotizing vasculitis of small arteries and veins as well as extravascular granuloma characterizes this syndrome. In individual patients, making a clear-cut distinction between HES and Churg-Strauss syndrome may not be possible.

Kimura’s Disease

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, or Kimura’s disease (first described in 1948 [99]) may be distinguished partly by histopathology and does not extend beyond the target organ. Kimura’s disease mostly occurs in young Asian men and presents with massive subcutaneous swelling or nodules that mostly affect the head and is associated with regional lymphadenopathy [100–102]. In some cases, an association with renal diseases has been reported [31, 103]. Peripheral eosinophil counts as well as serum IgE levels are elevated in many cases [31]. In a single case, a mild to moderate effect of mepolizumab, an anti–IL-5 monoclonal antibody, was reported [104].

Parasitosis

The diagnosis of HES also requires that eosinophilias of other etiologies, such as eosinophil-eliciting helminthic parasites, be excluded. Another important differential diagnosis is parasitic diseases, which may resemble features of other eosinophil disorders. Filarial and other helminth infections, such as Strongyloides spp and toxocara, may induce eosinophilia, possibly linked with further manifestations such as skin symptoms (urticaria and angioedema). Strongyloides stercoralis may cause marked eosinophilia that is difficult to diagnose solely by stool examination, and can develop into a disseminated, often fatal disease (“hyperinfection syndrome”) in patients receiving immunosuppressive agents. Indeed, HES has been misdiagnosed in patients with unsuspected parasitosis. Serial stool examinations as well as serologic tests must be performed in a patient with hypereosinophilia.

Therapy

HES is a life-threatening disorder with significant morbidity and mortality. Patients need to be monitored closely. As the heart is one of the primary organ syndromes affected, regular echocardiograms and high-vigilance monitoring for vasculopathy, hypercoagulation, and thrombosis are key factors. For confirmed HES patients, keeping the eosinophil level low is crucial, and medication should be adjusted accordingly [105, 106]. Serum eosinophil levels should be kept under 500/μL, and in some patients under 200/mL [106–108].

In the past, certain characteristics were found to be useful in predicting the response to corticosteroid therapy. The presence of angioedema and elevated serum IgE was associated with good responses to corticosteroid therapy [59, 108]. In corticosteroid-unresponsive patients, hydroxyurea can be administered. Antihistamines were evaluated and found to be ineffective. In patients with skin symptoms such as eczematous lesions, PUVA therapy and UVA1 phototherapy [65] as well as treatment with dapsone have been successful in some cases [109]. PUVA bath therapy has been used in single cases to treat hypereosinophilic dermatitis and seems to be a practical treatment modality without systemic side effects for patients [110].

In the case of patients presenting with myeloproliferative features of HES, imatinib is the first-line therapy. Early detection of FIP1L1–PDGFRA in patients with chronic unexplained hypereosinophilia is considered essential, as its presence is associated with high spontaneous morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, PCR for fusion gene detections and FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) for demonstration of a CHIC2 deletion should be performed by specialized centers. Imatinib is associated with cardiac, liver, and gastrointestinal toxicity but is generally well-tolerated compared with chemotherapy. Also, even if a patient is FIPL1–PDGFRA negative, treatment with imatinib may be initiated because a response rate of 25% in patients without this fusion gene is reported [89]. The initial dose should be 400 mg, and it may be necessary to combine with other agents such as corticosteroids initially. Imatinib doses below 100 mg/day are not recommended, as imatinib-resistant subclones could emerge in patients under suboptimal treatment conditions [17]. The ideal dose of imatinib is selected as one to induce and maintain molecular remission; thereby, eosinophil levels generally lower within days, while the disappearance of the molecular defect generally takes several months [40].

In other variants, efficacy studies and clinical experience have proven corticosteroids to be the first-line agents [87]. Most patients respond to steroids; however, for long-term use (or steroid-unresponsive patients), steroid-sparing agents such as hydroxyurea and vincristine may be administered. Furthermore, in single cases, successful long-term control by using etoposide has been reported [111]. Additional therapies for HES are interferon-α [97, 112], cyclosporine, and alemtuzumab, which targets the CD52 antigen that has been shown within the past few years to be effective as well [113]. Interferon-α has been reported to be successful in treating HES patients with features of myeloproliferative disease and may induce partial regression of pathogenic CD3−CD4+ T cells [19, 35]. Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody, and the CD52 is expressed on T cells and eosinophils; therefore, this agent targets T cells as well as eosinophils. Limited experience suggests alemtuzumab to be a valuable therapy for advanced HES or CEL refractory to standard therapies, and supports the clinical evaluation of alemtuzumab in a larger trial [114]. However, the efficacy and the risk/benefit of alemtuzumab must be investigated in a larger cohort of patient or on a case-by-case basis. Interestingly, tailored dosing of alemtuzumab, based on the absolute numbers of aberrant T cells in peripheral blood, has been recommended for patients with Sézary syndrome.

Mepolizumab, an anti–IL-5 antibody, is a drug that is effective. It is a fully humanized anti–IL-5 monoclonal immunoglobulin antibody (IgG1κ monoclonal antibody) and blocks binding of human IL-5 to the α chain of the IL-5 receptor complex expressed on the eosinophil cell surface [115]. In preliminary studies of healthy volunteers and patients with atopy, mepolizumab had few side effects and lowered blood eosinophil levels [19, 104, 116–118]. Subsequent studies suggested that mepolizumab may have clinical value in patients with HES [20]. These initial reports led to an international multicenter study that showed that treatment with mepolizumab can result in long-term improvement and a corticoid-sparing effect for HES patients negative for FIP1L1–PDGFRA. It has been shown to be effective in lowering eosinophils and steroid doses and to be well-tolerated [32]. A recent review pointed out that mepolizumab may be effective for long-term treatment of patients with HES [87].

In patients who respond to therapy, the inflammatory infiltrate and the blood eosinophilia are rapidly reduced. Therefore, in practical terms, the diagnostic work-up recommended (and referred to dermatological clinics) that skin biopsies should be performed before onset of therapy. In patients treated with imatinib, the potential improvement of most of the features of M-HES, including remission of FIP1L1–PDGFRA positivity, reduction of serum tryptase, disappearance of the atypical spindle-shaped mast cells, and improvement of myelofibrosis in bone marrow, is described [119]. Also, in patients with the lymphocytic variant, remission of blood and tissue eosinophilia as well as a decrease in serum TARC levels after different treatment modalities may be observed [20]. After treatment with steroids or the anti–IL-5 antibody mepolizumab, inflammatory infiltrate and eosinophils were reduced rapidly.

Conclusions

Though rare, HES have gained increasing interest in the medical community since the pathogenic mechanisms underlying the disease have been more clearly elucidated in certain subgroups, which explains different features and diverging prognosis in patients. On the basis of cellular and molecular investigations, it has become possible to classify patients with HES into defined pathogenic variants involving either myeloid or lymphoid cells. The differences in molecular pathogenesis are directly related to the clinical symptomatology, complications, and prognosis. Based on underlying molecular and functional abnormalities, therapeutic perspectives have changed radically. Immunosuppressive agents may no longer be necessary to control hypereosinophilia in all patients, and it has become possible to treat patients by targeting the molecules driving the disease. Common skin symptoms that may be an important clue to diagnosis consist of angioedema and urticarial, eczematous, and pruriginous lesions.

The management of HES patients remains a challenge, and collaboration with experienced physicians and centers is advisable. Correct pathogenic classification, which is necessary for treatment, depends on techniques that are not available on a routine basis. Moreover, treatment with monoclonal antibodies such as anti–IL-5 monoclonal antibodies is not yet officially available, but these agents are assessed in clinical trials and may be an option for patients in the near future.

References

Griffin H. Persistant eosinophilia with hyperleucocytosis and splenomegaly. Am J Med Sci. 1919;158:618–29.

Hardy WR, Anderson R. The hypereosinophilic syndrome. Ann Intern Med Sci. 1968;158:618–29.

Weller PF. Eosinophils: structure and functions. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:85–91.

Weller PF, Bubley GJ. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood. 1994;83:2759–79.

Spry CJ. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: clinical features, laboratory findings and treatment. Allergy. 1982;37(8):539–51.

Weller PF, Dvorak AM. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:583–5.

Gleich GJ, Schroeter AL, Marcoux P, et al. Episodic angioedema associated with eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1621–6.

Sheikh J, Weller PF. Clinical overview of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27(3):333–55.

Chusid MJ, Dale CD, West BC. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of 14 cases with review of the literature. Medicine. 1975;54:1–27.

Sheikh J, Weller PF. Advances in diagnosis &treatment of eosinophilia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(1):3–8.

Schwartz LB, Sheikh J, Singh A. Current strategies in the management of hypereosinophilic syndrome, including mepolizumab. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(8):1933–46.

Simon HU, Rothenberg ME, Bochner BS, Weller PF, Wardlaw AJ, Wechsler ME, Rosenwasser LJ, Roufosse F, Gleich GJ, Klion AD. Refining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndrome. JACI. 2010;126(1):45–9.

Roufosse F, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative variants. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:158–70.

Ring J. Allergy in practice. New York: Springer Berlin; 2005.

Ring J, Ruzicka T, Przybilla B, editors. Handbook of atopic eczema. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Berlin; 2006.

Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. The hypereosinophilic syndrome revisited. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:169–84.

Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. Recent advances in the pathogenesis and management of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Allergy. 2004;59:673–89.

Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. Lymphocytic variant of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27(3):389–413.

Simon HU, Plötz SG, Dummer R, Blaser K. Abnormal clones of T cells producing interleukin-5 in idiopathic eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(15):1112–20.

Plötz SG, Simon HU, Darsow U, et al. Use of an anti-interleukin-5 antibody in the hypereosinophilic syndrome with eosinophilic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(24):2334–9.

Cools J, De Angelo D, Gotlib J, et al. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGRA and FIP1L1 genes as therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(13):1201–14.

Klion AD, Noel P, Akin C, et al. Elevated serum tryptase levels identify a subset of patients with a myeloproliferative variant of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome associated with tissue fibrosis, poor prognosis, and imatinib responsiveness. Blood. 2003;101(12):4660–6.

Klion AD, Bochner BS, Gleich GJ, et al. The Hypereosinophilic Syndromes Working Group. Approaches to the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes: a workshop summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(6):1292–302.

Reiter A, Grimwade D, Cross NC. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of eosinophilia-associated chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Haematologica. 2007;92(9):1153–8.

Reiter A, Inverbizzi R, Cross NC, Cazzola M. Molecular basis of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2009;94(12):1634–8.

Gleich GF, Leifermann KM, Pardanani A, et al. Treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome with imatinib mesilate. Lancet. 2002;359:1577–8.

Valent P. Pathogenesis, classification and therapy of eosinophilia and eosinophilic disorders. Blood Rev Med. 2003;23:157–65.

Bain BJ. Relationship between idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic leukaemia, and systemic mastocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2004;77(1):82–5.

Leiferman KM, Gleich GJ. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: case presentation and update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):50–8.

Leiferman KM, O’Duffy JD, Perry HO, et al. Recurrent incapacitating mucosal ulcerations. A prodrome of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. JAMA. 1982;247(7):1018–20.

Leiferman KM, Gleich GJ, Peters MS. Dermatologic manifestations of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27(3):415–41.

Rothenberg ME, Klion AD, Roufosse FE, et al. Treatment of patients with the hypereosinophilic syndrome with mepolizumab. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1215–28.

Sanderson CJ. Pharmacological implications of interleukin-5 in the control of eosinophilia. Adv Pharmacol. 1992;23:163–77.

Sanderson CJ. Interleukin-5, eosinophils, and disease. Blood. 1992;79(12):3101–9.

Cogan E, Schandene L, Crusiaux A, et al. Brief report: clonal proliferation of type 2 helper T cells in a man with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:535–8.

Simon HU, Yousefi S, Dommann-Scherrer C, et al. Expansion of cytokine-producing CD4-CD8- T cells associated with abnormal Fas expression and hypereosinophilia. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1071–82.

Roufosse F, Schadene L, Sibille C, et al. Clonal Th2 lymphocytes in patients with the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Hematol. 2000;109:540–8.

Helbig G, Wieczorkiewicz A, Dziaczkowska-Suszek J, et al. T-cell abnormalities are present at high frequencies in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Haematologica. 2009;94:1236–41.

Plötz SG, Dibbert B, Abeck D, et al. Bcl-2 expression by eosinophils in a patient with hypereosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:1037–40.

Roufosse F. Hypereosinophilic syndrome variants: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Haematologica. 2009;94:1188–93.

Spry CJ, Kay AB, Gleich GJ. Eosinophils. Immunol Today. 1992;13:384–7.

Plotz SG, Abeck D, Seitzer U, Hein R, Ring J. UVA1 for hypereosinophilic syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:221.

De Lavareille A, Roufosse F, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, et al. High serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine levels in the lymphocytic variant of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:476–9.

Simon HU, Plotz SG, Simon D, et al. Clinical and immunological features of patients with interleukin-5-producing T cell clones and eosinophilia. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2001;124(1–3):242–5.

O’Shea JJ, Jaffe ES, Lane HC, et al. Peripheral T cell lymphoma presenting as hypereosinophilia with vasculitis. Clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):539–45.

Moraillon I, Bagot M, Bourneriaas I, et al. Hypereosinophilic syndrome with pachyderma preceding lymphoma. Treatment with interferon alpha. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;118(11):883–5.

Kim CJ, Park SH, Chi JG. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome terminating as disseminated T-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1991;67(4):1064–9.

Simon D, Simon HU. Eosinophilic disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1291–300.

Fauci AS, Harley JB, Roberts WC, et al. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clinical, pathophysiologic and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97(1):78–91.

Parillo JE, Fauci AS, Wolff SM. Therapy of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:167–72.

Kazmierowski JA, Chusid MJ, Parillo JE, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:531–5.

Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Erythema annulare centrifugum as the presenting sign of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Cutis. 1985;35:53–8.

Milijkovic J, Bartenev I. Hypereosinophilic dermatitis-like erythema annulare centrifugum in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(2):228–31.

Ohtani T, Okamoto K, Kaminaka C, et al. Digital gangrene associated with idiopathic hypereosinophilia: treatment with allogeneic cultured dermal substitute (CDS). Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14(3):168–71.

Jang KA, Lim YS, Cchoi JH, et al. Hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting as cutaneous necrotizing eosinophilic vasculitis and Raynaud’s phenomenon complicated by digital gangrene. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(3):641–4.

Bogenrieder T, Griese DP, Schiffner R, et al. Well’s syndrome as a manifestation of hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(6):978–82.

Tsuji Y, Kawashima T, Yokota K, et al. Well’s syndrome as a manifestation of hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(4):811–2.

Plötz SG, Abeck D, Behrendt H, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome). Hautarzt. 2000;51(3):182–6.

Butterfield JH, Leifermann KM, Abrams J, et al. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-5 in patients with the syndrome of episodic angioedema and eosinophilia. Blood. 1992;79:688–92.

Banerji A, Weller PF, Sheikh J. Cytokine-associated angioedema syndromes including episodic angioedema with eosinophilia (Gleich’s syndrome). Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26(4):769–81.

Leiferman KM, Loegering DA, Gleich GJ. Production of wheal-and-flare skin reactions by eosinophil granule proteins. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82:414.

Leiferman KM, Peter MS. Eosinophils in cutaneous diseases. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest B, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine, 7th ed, Chap 35. New York Chicago: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 2008.

Jacyk WK, Simson LW, Slater DN, Leiferman KM. Pachydermatous eosinophilic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:474–4698.

Plötz SG, Simon HU, Ring J. Hautmanifestationen bei Hypereosinophiliesyndrom. Allergologie. 1998;21:489–98.

Plötz SG, Abeck D, Hein R, Ring J. High-dose UVA1 for hypereosinophilic syndrome. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290:81.

Butterfield JH, Gleich GJ. Interferon alpha treatment of six patients with the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(9):648–53.

Hendren WG, Jones EL, Smith MD. Aortic and mitral valve replacement in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46(5):570–1.

Vandenberghe P, Wlodarska I, Michaux L, et al. Clinical and molecular features of FIP1L1-PDFGRA (+) chronic eosinophilic leukemias. Leukemia. 2004;18(4):734–42.

Rotoli B, Catalano L, Galderisi M, et al. Rapid reversion of Loeffler’s endocarditis by imatinib in early stage clonal hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(12):2503–7.

Moore PM, Harley JB, Fauci AS. Neurologic dysfunction in the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102(1):109–14.

Monaco S, Lucci B, Laperchia N, et al. Polyneuropathy in hypereosinophilic syndrome. Neurology. 1988;38(3):494–6.

Lefebvre C, Bletry O, Degoulet P, et al. Facteurs pronostiques du syndrome hypereosinophilique. Etude de 40 observations. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1989;140:253–7.

Cordier JF, Faure M, Hermier C, Brune J. Pleural effusions in an overlap syndrome of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome and erythema elevatum diutinum. Eur Respir J. 1990;3(1):115–8.

Levesque H, Elie-Legrand MC, Thorel JM, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with predominant digestive manifestations or eosinophilic gastroenteritis? a propos of 2 cases. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14(6–7):586–8.

Scheurlen M, Mork H, Weber P. Hypereosinophilic syndrome resembling chronic inflammatory bowel disease with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14(1):59–63.

Croffy B, Kopelman R, Kaplan M. Hypereosinophilic syndrome. Association with chronic active hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33(2):233–9.

Elouaer-Blanc L, Zafrani ES, Farcet JP, et al. Hepatic vein obstruction in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(4):751–3.

Eugene C, Gury B, Bergue A, Quevauvilliers J. Icterus disclosing pancreatic involvement in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1984;8(12):966–9.

Chaine G, Davies J, Kohner EM, et al. Ophthalmologic abnormalities in the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Opthalmology. 1982;89(12):1348–56.

Binaghi M, Perrenoud F, Dhermy P, et al. Hypereosinophilic syndrome with ocular involvement. J Fr Opthalmol. 1985;8(4):309–14.

Takekawa M, Imai K, Adachi M, et al. Hypereosinophilic syndrome accompanied with necrosis of finger tips. Intern Med. 1992;31:1262–6.

Trueb RM, Lubbe J, Torricelli R, et al. Eosinophilic myositis with eosinophilic cellulitis like skin lesions. Association with increased serum levels of eosinophil cationic proteins and interleukin-5. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:203–6.

Trueb RM, Pericin M, Winzeler B, et al. Eosinophilic myositis/perimyositis: frequence and spectrum of cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:385–91.

Schooley RT, Flaum MA, Gralnick HR, Fauci AS. A clinicopathologic correlation of the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome II: clinical manifestations. Blood. 1991;58:1021–6.

Flaum MA, Schooley RT, Fauce AS, Gralnick HR. A clinicopathologic correlation of the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood. 1981;58(5):1012–20.

Brugnoni D, Airo P, Rossi G, et al. A case of hypereosinophilic syndrome is associated with the expansion of a CD3− CD4+ T-cell population able to secrete large amounts of Interleukin-5. Blood. 1996;87:1416–22.

Busse WW, Ring J, Huss-Marp J, Kahn E. A review of treatment with mepolizumab, an anti-IL-5 mAb, in hypereosinophilic syndromes and asthma. JACI. 2010;125(4):803–13.

Jovanovic JV, Score J, Waghorn K, et al. Low-dose imatinib mesylate leads to rapid induction of major molecular responses and achievement of complete molecular remission in FIP1L1-PDGFRA-positive chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(11):4635–40.

Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH, et al. Hypereosinophilic syndromes: a multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1319–25.

Chikama R, Hosokawa M, Miyazawa T, et al. Nonepisodic angioedema associated with eosinophilia. Report of 4 cases and review of 33 young female patients reported in Japan. Dermatology. 1998;197:321–5.

Spigel T, Winkelmann RK. Wells’ syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:611–3.

Kamani N, Lipsitz PJ. Eosinophilic cellulitis in a family. Pediatr Dermatol. 1987;4:220–4.

Peters MS, Schroeter AL, Gleich GJ. Immunofluorescence identification of eosinophil granule major basic protein in the flame figures of Wells’ syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:141–8.

Yagi H, Tokura Y, Matsushita K, et al. Well’s syndrome: a pathogenetic role for circulating CD4 + CD7− T-cells expressing Interleukin-5 mRNA. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:918–23.

Nir MA, Westfried M. Hypereosinophilic dermatitis. A distinct manifestation of the hypereosinopilie syndrome with response to dapsone. Dermatology. 1981;162:444–50.

Schmelas A, Drobnitsch I, Schneider I. Hypereosinophilic dermatitis with response to ketotifen and sulfone. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1986;172(7):397–402.

Butterfield JH, Leifermann KM, Gleich GJ. Nodules, eosinophilia, rheumatism, dermatitis and swelling (NERDS): a novel eosinophilic disorder. Clin Exp Allergy. 1993;23:571–80.

Pardanani A, Brockman SF, Paternoster SF, et al. FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion: prevalence and clinicopathologic correlates in 89 consecutive patients with moderate to severe eosinophilia. Blood. 2004;104(10):3038–45.

Kimura T, Yoshimura S, Ishikawa E. Unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic changes in lymphatic tissue. Trans Jpn Soc Pathol. 1948;13:179–80.

Kung IT, Gibson JB, Bannatyne PM. Kimura’s disease: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases and its distinction from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Pathology. 1984;16(1):39–44.

Wang TF, Liu SH, Kao CH, et al. Kimura’s disease with generalized lymphadenopathy demonstrated by positron emission topography scan. Intern Med. 2006;45(12):775–8.

Chun SI. Kimura’s disease and ALHE with eosinophilia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:954.

Conelly A, Powell HR, Chan YF, et al. Vincristine treatment of nephrotic syndrome complicated by Kimura’s disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(4):516–8.

Braun-Falco M, Fischer S, Plotz SG, Ring J. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia treated with anti-interleukin-5 antibody (mepolizumab). Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(5):1103–4.

Klion AD. Approach to the therapy of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:551–60.

Simon HU, Cools J. Novel approaches to therapy of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:519–27.

Klion AD, How I. treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood. 2009;114:3736–41.

Gleich GJ, Leifermann KM. The hypereosinophilic syndromes: current concepts and treatments. Br J Hematol. 2009;145:271–85.

Van den Hoogenband HM, van den Berg WH, van Diggelson MW. PUVA-therapy in the treatment of skin lesions of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;7:267–72.

Eberlein A, von Kobyletzki G, Gruss C, et al. Erfolgreiche Monotherapie der hypreosinophilen Dermatitis mit PUVA-Bad-Photochemotherapie. Hautarzt. 1997;11:820–43.

Smit AJ, van Essen LH, de Vries EG. Successful long-term control of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with etoposide. Cancer. 1991;67:2826–7.

Zielinski RM, Lawrence WD. Interferon alpha for the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:716–8.

Sefcick A, Sowter D, Da Gupta E, et al. Alemtuzumab therapy for refractory idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:558–9.

Verstovsek S, Tefferi A, Kantarjian H, et al. Alemtuzumab therapy for hypereosinophilic syndrome and chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(1):268–73.

Simon D, Braathen LR, Simon HU. Anti-interleukin-5 therapy for eosinophilic diseases. Hautarzt. 2007;122:124–7.

Leckie MF, ten Brinke A, Khan J, et al. Effects of recombinant human interleukin-12 on eosinophils, airway hyper-responsiveness, and the late asthmatic response. Lancet. 2000;356:2149–53.

Oldhoff JM, Darsow U, Werfel T, et al. Anti-IL-5 recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody (mepolizumab) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2005;60:693–6.

Kay AB, Klion AD. Anti-interleukin-5 therapy for asthma and hypereosinophilic syndrome. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;114:1449–55.

Klion AD, Robyn J, Maric I, et al. Relapse following discontinuation of imatinib mesylate therapy for FIP1L1/PDGFRA-positive chronic eosinophilic leukaemia: implications for optimal dosing. Blood. 2007;110:3552–6.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plötz, S.G., Hüttig, B., Aigner, B. et al. Clinical Overview of Cutaneous Features in Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 12, 85–98 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-012-0241-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-012-0241-z