Abstract

Purpose

The successful transition of childhood cancer survivors from pediatric- to adult-focused long-term follow-up care is crucial and can be a critical period. Knowledge of current transition practices, especially regarding barriers and facilitators perceived by survivors and health care professionals, is important to develop sustainable transition processes and implement them into daily clinical practice. We performed a systematic review with the aim of assessing transition practices, readiness tools, and barriers and facilitators.

Methods

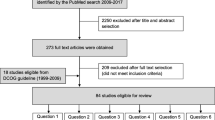

We searched three databases (PubMed, Embase/Ovid, CINAHL) and included studies published between January 2000 and January 2020. We performed this review according to the PRISMA guidelines and registered the study protocol on PROSPERO; two reviewers independently extracted the content of the included studies.

Results

We included 26 studies: six studies described current transition practices, six assessed transition readiness tools, and 15 assessed barriers and facilitators to transition.

Conclusion

The current literature describing transition practices is limited and overlooks adherence to follow-up care as a surrogate marker of transition success. However, the literature provides deep insight into barriers and facilitators to transition and theoretical considerations for the assessment of transition readiness. We showed that knowledge and education are key facilitators to transition that should be integrated into transition practices tailored to the individual needs of each survivor and the possibilities and limitations of each country’s health care system.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

The current knowledge on barriers and facilitators on transition should be implemented in clinical practice to support sustainable transition processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Most children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer will become long-term survivors. There is a broad international consensus that most of these childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) need life-long follow-up care, as the majority experience one or more late effects due to the cancer treatment received [1, 2]. The goal of long-term follow-up (LTFU) care is to reduce the burden of late effects among CCSs by prevention, early detection, or adequate treatment, which ultimately leads to an overall improvement in the CCSs’ quality of life. Today, many adolescent and adult CCSs discontinue regular follow-up care once they have left the pediatric setting, with a steady drop off over time after treatment completion [3,4,5]. The change in LTFU care from the pediatric to adult setting is referred to as a transition, and it has been generally defined as an “active, planned, coordinated, comprehensive, multidisciplinary process to enable childhood and adolescent cancer survivors to effectively and harmoniously transfer from child-centered to adult-oriented healthcare systems” [6]. The transition process itself is closely linked to the following LTFU care models, which can be implemented in different ways [7,8,9,10]. In the cancer center-based model, CCSs either transition directly from pediatric to adult oncology or internal medicine as a one-step process or undergo a stepwise transition carried out by a mixed team of pediatric and adult health care professionals (HCPs) before finally switching to adult care. Variants of this model involve specialized LTFU clinics with multidisciplinary teams that provide life-long LTFU care. In primary care models, CCSs transition to general practitioners with adult specialist consultations as needed (e.g., cardiologist). In shared care models, LTFU care is provided by primary care physicians in collaboration with a cancer center.

Many obstacles can hinder the practical implementation of these transition processes, such as barriers at the levels of the survivor, family, providers, and health care system. The ideal transition would overcome barriers at all levels and would take facilitators and needs into account.

Many publications have reported on different LTFU care models, but the literature on the actual transition process, including barriers and facilitators and measures of the success of different transition processes, is scarce. This systematic review aims to close this knowledge gap. We aim to provide comprehensive insight into current transition practices for CCSs from pediatric to adult LTFU care; to describe tools used in transitional care; to summarize barriers and facilitators to the transition process from CCSs’, parents’, and health care professionals’ points of view; and to assess loss to follow-up in relation to different transition practices.

Methods

We performed this review according to the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses [11] and registered the protocol on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42019132786).

Literature search

We conducted a systematic literature search with the aid of an experienced information specialist in February 2020 and searched three databases (PubMed, Embase/Ovid, CINAHL) (Supplemental S1). We restricted the search to studies published from January 2000 to January 2020 and studies available in English or German. We built the search strategy for all three databases around four concepts. We identified MeSH terms and free text words for each concept, which we finally combined. For the population of interest, we included the concepts of “cancer” (including different types of childhood cancers), “children and adolescents”, and “survivors”. For the outcome, we chose terms related to “transition”. In addition to the three bibliographic databases, we searched Google Scholar in English (“childhood cancer | childhood cancer survivor AND aftercare | follow-up”) and German (“Kinderkrebs transition| Nachsorge”). For each review article identified with our search, we screened the reference list for relevant original articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in this review, the studies had to report on cancer survivors who were diagnosed during childhood or adolescence, who completed their cancer treatment and were in the process of transition or had finished transition when included in the respective study. The term “transition” in the context of this review only refers to the change from pediatric- to adult-focused LTFU care. For a study cohort to be considered “children or adolescents”, at least 75% of participants had to be aged less than 18 years at the time of the cancer diagnosis. We excluded studies that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, case reports, case series (n ≤ 14), commentaries, editorial letters, poster abstracts, and review articles.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of this review were current transition practices and care needs during transition. The assessment of current transition practices also included information on transition readiness tools, as these tools can be part of transition practices. Care needs included barriers and facilitators to transition and could be reported by CSSs, parents, or health care professionals. Loss to follow-up during transition was assessed as a secondary outcome, as this might be an indirect marker of whether a transition practice is successful.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (MO and SD) screened all titles and abstracts separately and excluded those not fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by a third reviewer (KS). The same reviewers (MO and SD) independently checked all retrieved full texts for adherence. In case of disagreement or doubts, a third reviewer (KS) was approached. Data from the eligible studies were extracted to a standard sheet including the first author, year of publication, CCSs’ age at diagnosis and time of the study, follow-up time, sample size, role of the study participants (survivor, parent, or health care professional), study design, type of transition model, barriers and facilitators to transition, perception of transition, and loss to follow-up. To summarize barriers and facilitators, we first listed all of them in their original wording and subsequently grouped them based on content. We assessed the quality, relevance, and reliability of each included study on barriers and facilitators by using the appropriate critical appraisal tool from the Joanna Briggs Institute [12], including the checklists for qualitative research and cross-sectional studies (Supplemental S2). Since these tools do not use any categorization, we made a classification with three categories. If all criteria of the respective checklist were fulfilled, we assigned the study to “Quality 1”. If a qualitative study did not include a statement locating the researcher culturally and theoretically or a summary of the influence of the researcher on the research and vice versa, we assigned the study to “Quality 2”. If a cross-sectional study did not assess confounders or did not clearly state how confounders were selected and used in the analysis, the study was assigned to “Quality 2”. If an additional point from the checklist for both types of studies was insufficiently covered, we assigned the study to “Quality 3”.

Results

Literature search result

Our search identified 6156 records. After screening the titles and abstracts, we excluded 5951 records. Finally, we included 26 studies, one of which reported on two of the assessed outcomes [13] (Supplemental 3).

Study findings

Current transition practices

We identified six studies describing the transition process in detail, one of which described two processes (Table 1). Three studies discussed transition processes that ultimately reflected shared care models including the involvement of general practitioners [14,15,16]. Three studies described the transition to adult LTFU clinics [13, 17, 18], and one of these studies additionally discussed the transition to LTFU care provided by a combination of pediatric and adult HCPs [13]. We included six studies outlining five different tools, such as scales, questionnaires, and models, used to assess transition readiness among CCSs (Table 2) [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Although the applicability of four of the tools has been validated, these tools have not yet been implemented in daily clinical practice [19,20,21, 23].

Barriers and facilitators

Fifteen studies reported on barriers and facilitators encountered when CCSs transitioned from pediatric to adult LTFU care (Table 3). Seven studies included survivors’ perspectives [13, 26, 31,32,33, 37, 38], five included HCPs’ perspectives [27, 29, 34,35,36], two included survivors’ and parents’ perspectives [25, 30], and one included survivors’, parents’, and HCPs’ perspectives [28]. The term “HCP” was used to refer to professionals from different disciplines, such as pediatric oncologists, primary care physicians, health care practitioners, nurses, nurse practitioners, psychologists, and social workers. Overall, 523 survivors, 48 parents, and 523 HCPs participated in these 15 studies. After the systematic collection of all mentioned barriers and facilitators, we grouped the barriers and facilitators into eight categories (Table 4):

-

1.

CCSs’ self-management skills, including knowledge, education, and empowerment

-

2.

Social environment, including family, friends, and peers

-

3.

CCSs’ personal feelings and emotions

-

4.

Pediatric setting

-

5.

Adult setting

-

6.

Financial issues and insurance

-

7.

Communication

-

8.

Structural circumstances including organization of transition

Barriers and facilitators in the “CCSs’ self-management skills” category were the most frequently reported. Certain factors, such as fear and anxiety, were reported to act as facilitators for some CCSs and as barriers for other CCSs. Fear of cancer relapse could motivate one CCS to attend LTFU care but hinder another CCS from doing so. The impact of family, and especially parents, was mentioned in a similar way; while some CCSs wanted to gain independence in the process of transition, others needed their families’ support even as young adults.

Impact of transition programs on loss-to follow-up

We could not identify any study that evaluated the transition process and its success longitudinally through an assessment of the proportion of CCSs not successfully transitioned and lost to follow-up as a surrogate marker.

Discussion

Transition practices and barriers and facilitators to transition

Our review shows that the literature describing transition processes is limited and lacks evaluation of transition success. In contrast, the literature provides deep insight into barriers and facilitators to transition and theoretical considerations for the assessment of transition readiness.

Transition is crucial not only for the CCS population but also for adolescents and young adults with other chronic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease [39], diabetes [40, 41], and rheumatic diseases [42]. One study including adolescents with type 1 diabetes compared an unstructured transition to adult care with a structured transfer planned together with adult physicians. The authors showed that adolescents with a structured transfer had higher clinical attendance, lower HbA1c, and a more positive opinion of the transition process after 1 year than those with an unstructured transition [40]. The structured transfer included a transition coordinator, clear explanations about the process and clinical implications at each visit, and two joint consultations with pediatric and adult endocrinologists. In accordance, the factors “transition coordinator” and “knowing the adult setting before actual transfer” were frequently reported facilitators from the CCSs’ perspective. “Clear explanation/education” was also frequently mentioned by HCPs in the reviewed articles.

In this review, factors related to “CCSs’ self-management skills, including knowledge”, the setting of LTFU care (“pediatric setting” or “adult setting”), “communication”, and “structural circumstances” were identified as key factors for successful transition. CCSs’ knowledge deficits related to cancer history, risk of late effects, and importance of LTFU care were identified as major barriers that were mentioned by CCSs themselves and by HCPs. In addition, adult HCPs’ lack of knowledge regarding late effects and caring for CCSs was also mentioned repeatedly as a barrier. The finding on the importance of the knowledge and education of CCSs and HCPs about transition is in accordance with that of other reviews assessing adolescents with other chronic diseases [43, 44]. Therefore, education and empowerment of CCSs must be an important part of transition preparation. The second most frequently mentioned factor was related to the setting of LTFU care (pediatric vs adult) and confidence in the setting. CCSs’ and families’ attachment to the pediatric team and concerns about terminating that relationship can act as a barrier. On the other hand, building a relationship with and having confidence in the new provider can act as a facilitator. Building a new relationship takes time and in most cases cannot be established during one consultation hour. Therefore, survivors wish to start this new relationship with adult providers towards the end of their pediatric care, but when they are still in the pediatric setting. During the transfer from pediatric to adult care, communication is a third key factor. Good and clear communication between HCPs and survivors, between HCPs and parents, and between pediatric and adult HCPs act as facilitators. Finally, the structure and organization of the transition can either facilitate or hinder transition. Both CCSs and HCPs report that the transition should be well prepared for and planned within an established transition concept, that the timing should be individualized and that there should be assistance and flexibility in (re)scheduling appointments and having consultations combined on 1 day if multiple examinations are needed.

Cultural and country-specific differences

Transition practices are not uniform across the globe. Transitional care depends upon the possibilities of each country’s health care system. In many studies from the US, one major barrier to transition was a lack of health insurance. In contrast to the US, where health insurance is often dependent on employment, Canada and many European countries have compulsory health insurance. Countries also differ to a great extent in the distribution of and distance to health care facilities, which might also affect the transition models used and the willingness of CCSs to attend LTFU care. In larger countries, shared care models with the involvement of primary care physicians might be more convenient. In smaller countries, one or more centralized LTFU clinics can easily be reached by CCSs. This model of centralized LTFU care was presented in the Slovenian study by Jereb et al. [17] as a successful example. Acceptance of travel distances seems to be variable. The study by Granek et al. reported the use of transition and LTFU care models in Ontario with centralized LTFU clinics, and the survivors seemed to accept long travel distances [13]. All studies included in this review were conducted in first-world countries. The implementation of transition and LTFU care for CCSs in countries with limited resources needs to be investigated in the future. In addition to structures established by the state, such as health insurance, HCPs need to take the cultural background of the survivor and his or her family into account, as it might also affect the transition. The study by Casillas et al. provided insight into the needs of Latino CCSs and their parents [25]. Cancer stigma and its negative effect on the wider family was a barrier to transition. The involvement and support of the nuclear family, even for young adults, was highlighted as a facilitator. This finding was in contrast to those of other studies that emphasized the survivor’s independence and self-management skills as a requirement for successful transition.

Transition tools

Transition tools can be a helpful additional element in the preparation of CCSs to transition. They can help to detect knowledge gaps, fears, or uncertainties but also areas where the CCSs have their strength and resources. Through education to address knowledge gaps, psychological support to address fears, and reinforcement where strengths already exist, CCSs can be supported in their independence. Information on helpful resources and toolkits for transition of adolescents and young adults with chronic diseases for physicians and patients are also available online, but most of these tools are not specific for CCS. One site is “GotTransition” from the US [45], which provides information for young adults, parents and caregivers, and health care professionals. More focused on health care providers is the initiative from the American College of Physicians (ACP), which provides disease-specific toolkits (e.g., congenital heart disease or hemophilia) [46]. In other countries, specific guidelines are in preparation, such as the AWMF guideline for transition in Germany [47] or exist already, such as the NICE guideline in the UK [48]. In addition to these examples of overarching sources, there are many national, disease-specific transition programs, for example from the British Diabetic Association [49], programs linked to a specific clinic, such as for congenital heart defects in Bern [50] or links specifically for adolescents or young adults, as an example the page “la suite” from Paris [51].

Main features of the ideal transition

There is no uniform and ideal transition practice that fits each CCS and that can be applied similarly in every country. This review highlights several key features. The transition from pediatric- to adult-focused LTFU care should be individually adapted to the needs of each survivor. These needs and knowledge gaps can be identified by using transition tools. The transition should be a gradual process rather than a one-step change. Pediatric HCPs should start to prepare CCSs for transition well in advance and educate them on their cancer history, future risks and need for LTFU care. The transition process should be well structured and organized, ideally involving collaboration between the pediatric and adult HCPs. Finally, good communication between HCPs and survivors as well as between pediatric and adult HCPs is paramount to enable a smooth transfer.

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of this study lies in the thorough application of the systematic review methodology, including the performance of all steps of the review by two reviewers. The majority of included studies were qualitative studies, which led to small numbers of preselected CCSs. Therefore, the included studies might have been affected by participation and response bias. We assume that survivors who participated in these qualitative studies were generally more interested in LTFU care than those who did not participate. Therefore, we might have lacked the input of survivors who were less motivated in LTFU care and who were more at risk for loss to follow-up. Our review is limited by the lack of reporting on loss to follow-up, and therefore, a clear judgment on the performance of different transition practices is not possible.

Conclusion

Our systematic review highlights important aspects of the transition of CCSs from pediatric- to adult-focused LTFU care. To date, there is no single-best model of transitional care, and the current literature describing transition practices is limited and does not evaluate adherence to follow-up care as a surrogate marker of transition success. We showed that good knowledge, education, and communication among CCSs and HCPs are key facilitators to transition that must be integrated into transition practices and tailored to the individual needs of each survivor and the framework of each country’s health care system.

References

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82.

Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LCM, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJH, Heinen RC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Jama. 2007;297(24):2705–15.

Rebholz CE, von der Weid N, Michel G, Niggli FK, Kuehni CE, Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group (SPOG). Follow-up care amongst long-term childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(2):221–9.

Rokitka DA, Curtin C, Heffler JE, Zevon MA, Attwood K, Mahoney MC. Patterns of loss to follow-up care among childhood cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(1):67–73.

Freyer DR. Transition of care for young adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: rationale and approaches. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4810–8.

Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, Jorissen TW, Okinow NA, Orr DP, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(7):570–6.

Friedman DL, Freyer DR, Levitt GA. Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(2):159–68.

Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–24.

Singer S, Gianinazzi ME, Hohn A, Kuehni CE, Michel G. General practitioner involvement in follow-up of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(10):1565–73.

Eshelman-Kent D, Kinahan KE, Hobbie W, Landier W, Teal S, Friedman D, et al. Cancer survivorship practices, services, and delivery: a report from the Children's Oncology Group (COG) nursing discipline, adolescent/young adult, and late effects committees. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):345–57.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Joanna B Critical Appraisal Tools. Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools. Accessed 26 Apr 2020

Granek L, Nathan PC, Rosenberg-Yunger ZRS, D’Agostino N, Amin L, Barr RD, et al. Psychological factors impacting transition from paediatric to adult care by childhood cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):260–9.

Berger C, Casagranda L, Faure-Conter C, Freycon C, Isfan F, Robles A, et al. Long-term follow-up consultation after childhood cancer in the Rhone-Alpes region of France: feedback from adult survivors and their general practitioners. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(4):524–34.

Blaauwbroek R, Tuinier W, Meyboom-de Jong B, Kamps WA, Postma A. Shared care by paediatric oncologists and family doctors for long-term follow-up of adult childhood cancer survivors: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):232–8.

Costello AG, Nugent BD, Conover N, Moore A, Dempsey K, Tersak JM. shared care of childhood cancer survivors: a telemedicine feasibility study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(4):535–41.

Jereb B. Model for long-term follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;34(4):256–8.

McClellan W, Fulbright JM, Doolittle GC, Alsman K, Klemp JR, Ryan R, et al. A collaborative step-wise process to implementing an innovative clinic for adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(5):e147–55.

Bashore L, Bender J. Evaluation of the utility of a transition workbook in preparing adolescent and young adult cancer survivors for transition to adult services: a pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(2):111–8.

Klassen AF, Rosenberg-Yunger ZRS, D'Agostino NM, Cano SJ, Barr R, Syed I, et al. The development of scales to measure childhood cancer survivors' readiness for transition to long-term follow-up care as adults. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):1941–55.

Klassen AF, et al. Development and validation of a generic scale for use in transition programmes to measure self-management skills in adolescents with chronic health conditions: the TRANSITION-Q. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(4):547–58.

Schwartz LA, Hamilton JL, Brumley LD, Barakat LP, Deatrick JA, Szalda DE, et al. Development and content validation of the transition readiness inventory item Pool for adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(9):983–94.

Schwartz LA, Brumley LD, Tuchman LK, Barakat LP, Hobbie WL, Ginsberg JP, et al. Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness for transition to adult care. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(10):939–46.

Schwartz LA, et al. A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):883–95.

Casillas J, Kahn KL, Doose M, Landier W, Bhatia S, Hernandez J, et al. Transitioning childhood cancer survivors to adult-centered healthcare: insights from parents, adolescent, and young adult survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19(9):982–90.

Frederick NN, et al. Preparing childhood cancer survivors for transition to adult care: the young adult perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(10).

Kenney LB, Melvin P, Fishman LN, O'Sullivan-Oliveira J, Sawicki GS, Ziniel S, et al. Transition and transfer of childhood cancer survivors to adult care: a national survey of pediatric oncologists. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(2):346–52.

McCann L, Kearney N, Wengstrom Y. "It's just going to a new hospital ... that's it." Or is it? An experiential perspective on moving from pediatric to adult cancer services. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(5):E23–31.

Mouw MS, Wertman EA, Barrington C, Earp JAL. Care transitions in childhood cancer survivorship: providers' perspectives. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(1):111–9.

Nandakumar BS, et al. Attitudes and experiences of childhood cancer survivors transitioning from pediatric care to adult care. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(8):2743–50.

Quillen J, Bradley H, Calamaro C. Identifying barriers among childhood cancer survivors transitioning to adult health care. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34(1):20–7.

Rosenberg-Yunger ZR, et al. Barriers and facilitators of transition from pediatric to adult long-term follow-up care in childhood cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2(3):104–11.

Sadak KT, Dinofia A, Reaman G. Patient-perceived facilitators in the transition of care for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(8):1365–8.

Sadak KT, et al. Identifying metrics of success for transitional care practices in childhood cancer survivorship: a qualitative study of survivorship providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(11).

Sadak KT, et al. Transitional care practices, services, and delivery in childhood cancer survivor programs: a survey study of U.S. survivorship providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(8):e27793.

Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Fardell JE, Lawrence RA, Osborn M, et al. Models of childhood cancer survivorship care in Australia and New Zealand: strengths and challenges. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13(6):407–15.

Szalda D, Piece L, Brumley L, Li Y, Schapira MM, Wasik M, et al. Associates of engagement in adult-oriented follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(2):147–53.

van Laar M, Glaser A, Phillips RS, Feltbower RG, Stark DP. The impact of a managed transition of care upon psychosocial characteristics and patient satisfaction in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(9):2039–45.

Afzali A, Wahbeh G. Transition of pediatric to adult care in inflammatory bowel disease: is it as easy as 1, 2, 3? World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(20):3624–31.

Cadario F, Prodam F, Bellone S, Trada M, Binotti M, Trada M, et al. Transition process of patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) from paediatric to the adult health care service: a hospital-based approach. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;71(3):346–50.

Buschur EO, Glick B, Kamboj MK. Transition of care for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus from pediatric to adult health care systems. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6(4):373–82.

Sabbagh S, Ronis T, White PH. Pediatric rheumatology: addressing the transition to adult-orientated health care. Open Access Rheumatol. 2018;10:83–95.

Lugasi T, Achille M, Stevenson M. Patients' perspective on factors that facilitate transition from child-centered to adult-centered health care: a theory integrated metasummary of quantitative and qualitative studies. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(5):429–40.

Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(6):548–53.

The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health. GotTransition. Available from: https://www.gottransition.org/index.cfm. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

American College of Physicians (ACP). Pediatric to adult care transitions initiative. Available from: https://www.acponline.org/clinical-information/high-value-care/resources-for-clinicians/pediatric-to-adult-care-transitions-initiative. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF). Transition von der Pädiatrie in die Erwachsenenmedizin. Available from: https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/anmeldung/1/ll/186-001.html. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

National Institute for Health and care Excellence (NICE). Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng43. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

The British Diabetic Association. Transition of young people with diabetes from paediatric care to adult care (our position). Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/diagnosis-ongoing-management-monitoring/transition. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

Inselspital. Zentrum für angeborene Herzfehler - Übergang auf die GUCH. Available from: http://www.ang-herzfehler.ch/de/fuer-jugendliche-new/uebergang-auf-die-guch/. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

Assistance Hôpitaux Publique de Paris. La Suite. Available from: http://www.la-suite-necker.aphp.fr/hello/#_la-suite. Accessed 08 Jul 2020

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the librarians Beatrice Minder and Doris Kopp, University of Bern, for their support.

Funding

This publication was supported by a grant from the Swiss Cancer Research (HSR-4359-11-2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Maria Otth and Sibylle Denzler shared first authorship

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 674 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Otth, M., Denzler, S., Koenig, C. et al. Transition from pediatric to adult follow-up care in childhood cancer survivors—a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 15, 151–162 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00920-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00920-9