Abstract

Although research continues to debate the future of the marketing concept, practitioners have taken the lead, appraising customer experience management (CEM) as one of the most promising marketing approaches in consumer industries. In research, however, the notion of CEM is not well understood, is fragmented across a variety of contexts, and is insufficiently demarcated from other marketing management concepts. By integrating field-based insights of 52 managers engaging in CEM with supplementary literature, this study provides an empirically and theoretically solid conceptualization. Specifically, it introduces CEM as a higher-order resource of cultural mindsets toward customer experiences (CEs), strategic directions for designing CEs, and firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs, with the goals of achieving and sustaining long-term customer loyalty. We disclose a typology of four distinct CEM patterns, with firm size and exchange continuity delineating the pertinent contingency factors of this generalized understanding. Finally, we discuss the findings in relation to recent theoretical research, proposing that CEM can comprehensively systemize and serve the implementation of an evolving marketing concept.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The marketing landscape is changing. Given the overall challenge of digitalization associated with increasingly transparent, empowered, and collaborative consumer markets, several scholars have suggested rethinking central marketing practices and the current self-conception of marketing (Achrol and Kotler 2012; Chandler and Lusch 2014; Day 2011; Hult 2011; Webster and Lusch 2013). In turn, practitioners have begun appraising customer experience management (CEM) as one of the most promising management approaches for meeting these market challenges. A recent survey on marketing’s role in firms, for example, found that by 2016, 89% of firms expect to compete primarily by CEM, versus 36% in 2010 (Gartner 2014). According to another empirical report, CEM will become the most important attribute of the 1000 globally most innovative firms in the future (Jaruzelski et al. 2011), or as Steve Cannon, CEO at Mercedes Benz USA, noted: “customer experience is the new marketing” (Tierney 2014). Motivated by this trend, the overall objective of this study is to investigate the concept of CEM. In doing so, we aim to bridge researchers’ and practitioners’ perspectives of how to best tackle today’s and tomorrow’s market challenges by clarifying whether CEM can serve the implementation of an evolving marketing concept (Webster and Lusch 2013).

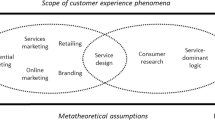

CEM is not well understood, even though it has been extensively highlighted in extant literature. As Fig. 1 illustrates, literature pointing to the notion of CEM is fragmented across the fields of customer experience (CE), CEM, and other marketing management conceptualizations. Importantly, whereas scholars have extensively discussed CE as the action object of CEM, scientific research on CEM itself is sparse (Fig. 1). The few studies available have focused on the service context, specifically the development of schemes and methods for service experience design, by drawing on the premises of service-dominant logic. Instead, since Pine and Gilmore’s (1998) seminal article on the experience economy, several applied writings have provided ad-hoc guidance (Fig. 1) for CEM, the “process of strategically managing a customer’s entire experience with a product or company” (Schmitt 2003, p. 17). Apparently, there is a lack of research that integrates different notions of CEM and that elaborates on its concrete underpinning in marketing management theory, investigating its nature, contingency factors, and feasibility as a stand-alone concept. That said, it is not surprising that 93% of more than 200 consulted firms engaging in CEM are hesitant about how to deploy it effectively (Temkin Group 2012). Therefore, we address this research gap by asking: What is CEM, and how can it be conceptualized?

Furthermore, CEM is a seemingly complex concept that has been attributed to various contexts. On the one hand, nascent CEM research is limited to a service context. On the other hand, extensive research with a consumer behavior focus on CEs is highly fragmented across service, product, online, branding, and retailing contexts (Fig. 1). Integrating previous literature pointing to the notion of CEM to conceptualize the phenomena therefore requires finding a “novel, simple, and thus parsimonious perspective that accommodates complexity” (MacInnis 2011, p. 146). Accordingly, scholars have called for research on CEM beyond the service/product dichotomy and certain industry settings (MSI 2012; Verhoef et al. 2009). We address this call by asking: Is CEM generalizable beyond the service context, and, if so, what are the pertinent contingency factors of such a novel understanding?

Last, CEM is highly interrelated with different research streams on marketing management. Blocker et al. (2011), Day (2011), and Karpen et al. (2012) for example indicate the need to extend market orientation (MO) by highlighting a firm’s orientation toward the entire CE from prepurchase to postpurchase situations. Regarding customer relationship management (CRM), Meyer and Schwager (2007) differentiate CRM (i.e., knowing customers and leveraging that data) from CEM (i.e., knowing how customers react and behave in real time and leveraging that data). Payne and Frow (2005, p. 172), however, consider these two aspects as included in a strategic perspective on CRM, which helps determine whether the “value proposition is likely to result in a superior CE.” These overlaps have also became evident in practice, with a management blogosphere asking, “Is CEM the new CRM?” (Davey 2012). Similarly, a growing number of studies on the pending future of the marketing concept have alluded to CEM as the appropriate approach to implement an evolving marketing concept (e.g., Achrol and Kotler 2012; Webster and Lusch 2013). Thoroughly investigating the concept of CEM therefore requires further clarifying its links to related concepts. We address this research gap by asking: How does CEM demarcate from other marketing (management) concepts?

To appropriately address these research gaps of the lack of an established conceptualization, generalization, and demarcation of CEM, we applied an exploratory, grounded theory procedure (Edmondson and McManus 2007). This procedure involved integrating field-based insights of 52 top and senior managers engaging in CEM with supplementary literature pointing to the notion of CEM (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the main literature with a CE and CEM focus and further summarizes the research contributions of the present study, which we discuss next.

First, this study provides an empirically and theoretically solid conceptualization of CEM. We introduce a grounded theory framework of CEM that pertains to different contexts and industries. Importantly, we identify the theoretical view on hierarchical operant resource compositions (Madhavaram and Hunt 2008) that is a combination of service-dominant logic, the resource-based view in marketing (Kozlenkova et al. 2014), and dynamic capabilities (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000), as the appropriate theoretical underpinning of CEM.

Second, though the grounded theory framework entails distilled commonalities (Eisenhardt 1989; Malshe and Sohi 2009) across a diverse set of firms in terms of size and industries, we identify important differences in terms of the emphasis on different framework categories. From our field data, we systemize these differences by disclosing a typology of four CEM patterns along two identified factors: (1) firm size and (2) exchange continuity of the firm’s core business model. This typology contributes to a better understanding of CEM by delineating its pertinent contingency factors, which is an important step to understanding the boundary conditions of a concept (Edmondson and McManus 2007).

Third, drawing on the previous two contributions, we position CEM within existing literature by discussing our findings in relation to MO and CRM, as well as theoretical studies on the pending future of the marketing concept. Specifically, we propose that CEM entails and extends the tenets of MO and CRM along its three main categories (cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities). By discussing the identified (sub)categories of our framework, we further propose that this extended marketing management concept serves the implementation of an evolving marketing concept. By relying on supportive literature, we systemize and describe it as a firm’s (1) cultural market network mindset, (2) strategic design of potentially firm-spanning value constellation propositions, and (3) dynamic system of capabilities for the realization of organizational ambidexterity (i.e., the synchronization and balancing of incremental and radical market innovations; Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008). We elaborate on this contribution in the discussion section of the study.

Research procedure

To answer our research questions, we applied a discovery-oriented, grounded theory procedure that involved the iterative collection and analysis of field data and literature to develop a theory “grounded” in these data. Before introducing the details of our procedure, we highlight three key reasons why grounded theory (Strauss 1987; Strauss and Corbin 1998) is the appropriate approach for answering the research questions of this study.

First, for studying phenomena that are not well understood, scholars recommend exploratory research procedures, such as grounded theory, that rely on field data collection and concept development (Closs et al. 2011; Edmondson and McManus 2007; Malshe and Sohi 2009). Grounded theory is one of the most established procedures in management and marketing research to develop a general theory of concepts (Hollmann et al. 2015; Johnson and Sohi 2015). As outlined in the introduction, research on CEM is still in its infancy, and the nature and organizational scope of CEM is not well understood. In this early and inconsistent stage of development, there is a need for theoretical and empirical research that integrates all early ideas, approaches, and research perspectives pointing to the notion of CEM. We therefore consider grounded theory most appropriate to study the concept of CEM.

Second, grounded theory procedures aim to capture and reduce the complexity of concepts that are socially constructed in the organizational reality of participants. In other words, grounded theory focuses on how social actors interact with their environment and other people to solve problems. Accordingly, emerging grounded theory frameworks, such as managerial concepts, are directly shaped by participants’ views and interpretations (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Hollmann et al. 2015; Malshe and Sohi 2009). Thereby, grounded theory helps the researcher to avoid misinterpretations of the problem solving activities of social actors or the overemphasis of prior research on the investigated concept. A grounded theory procedure is therefore appropriate to obtain a clear and complexity-reducing understanding (MacInnis 2011) of CEM by directly talking with diverse people who are engaging in this approach and then distilling identified commonalities for deriving a generalized CEM understanding across firm and industry contexts (Eisenhardt 1989).

The third reason is a consequence of the previous two points. One of the main principles of grounded theory is the continuous comparison of different sources of qualitative data (Closs et al. 2011). This implies that grounded theory encourages the combination of a qualitative field study and supplementary literature to develop theoretical frameworks that (1) integrate different bodies of knowledge, (2) extend previous knowledge, and thus (3) meet the “challenging, dual objectives of theoretical integration and renewal” (Yadav 2010, p. 6). Because, on the one hand, CEM notions are abundant and fragmented, but, on the other hand, CEM research is sparse, a grounded theory procedure allows us to synthesize extant literature and field-based insights to develop an integrated but novel and generalized understanding of CEM, hence meeting the dual objective of theory development (Yadav 2010).

Figure 2 provides an overview of our research procedure. The first step involved consulting the extant literature pointing to the notion of CEM (see Fig. 1). This helped us delineate the research questions, develop an interview guide, and select a purposive, initial field sample (Eisenhardt 1989; Morgan et al. 2005; Strauss 1987).

Sample and data collection

Consistent with other exploratory marketing studies (e.g., Challagalla et al. 2014; Malshe and Sohi 2009; Tuli et al. 2007), we applied a theoretical sampling plan to select in-depth interview participants who engage in CEM. Theoretical sampling is a non-random sampling scheme, the purpose of which is to obtain participants who can provide a deeper understanding of the topic and to sample participants in the course of the data analysis instead of determining them in advance. As such, data collection starts with purposive sampling (first stage) and continues with selective sampling (second stage), with the emerging findings directing the decision of which participants to consult next (Strauss and Corbin 1998).

In a first stage, we recruited participants during a conference on new perspectives of customer orientation that included the topic of CEM. In a second stage, we continually relied on a snowball technique of personal recommendations from the first stage (for a similar procedure, see Bradford 2015; Malshe and Sohi 2009) and also contacted a practitioner forum on CEM to further increase the theoretical relevance of participants. We ceased the sampling process when no new insights emerged from the field data, that is, when we reached theoretical saturation (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss and Corbin 1998).

During a 10-month period, we conducted 52 in-depth interviews with firm representatives, a configuration consistent with the sample sizes recommended for exploratory research (McCracken 1988). To provide a solid foundation of our second research question of whether CEM is a concept that is generalizable beyond the service context, we maximized the diversity among participants (Strauss and Corbin 1998) in terms of firm size and industries. Moreover, similar to prior research (Homburg et al. 2014; Malshe and Sohi 2009), we strived to obtain participants who vary in terms of working experience with CEM. Whereas some participants had just begun to be involved in CEM, others had employed CEM for several years already. As Table 2 illustrates, the majority of participants, especially from the second sampling stage, were senior and top managers working in marketing or strategy with at least 1 year and a maximum of 9 years of experience in CEM. The consulted firms represented a wide diversity in size and industries, which comprise both manufacturing (e.g., apparel, consumer electronics, health care) and services (e.g., information and communication, financial services, online retailing). The size of the 52 consulted firms varied between 97 and 164,000 employees, for an average of 34,117 employees. Providing an ID number for each interview participant, Table 2 links the subsequent quotations of interview participants (each with an ID indicated) with their respective sample characteristics.

Our interview guide consisted of three parts. The first part referred to characteristics of the participant and the firm (e.g., job position, organizational structure). The second part addressed the concept of CEM. We asked the managers about their understandings of CE and CEM as well as central approaches, organizational aspects, challenges, and success factors of CEM. In this main part of the interview, we encouraged the participants to offer examples, anecdotes, and additional details on potentially important issues (Glaser and Strauss 1967). This allowed us to interpret the resulting qualitative data with the necessary integrity, avoiding misinterpretations (Wallendorf and Belk 1989). We further phrased the questions in a nondirective and unobtrusive manner to avoid active listening (McCracken 1988). In the third part, we asked the participants for their opinions, clarifications, and examples regarding the categories derived during our coding procedure (see next section) and their interrelations. This helped us to check on the dependability of our emerging, industry-spanning CEM conceptualization (Lincoln and Guba 1985). To avoid directive biases, we put these questions at the end of each interview (Strauss and Corbin 1998).

Data analysis for grounded theory development

We audiotaped all interviews and transcribed the data verbatim, which amounted to 780 pages of single-spaced transcripts. The 52 firm interviews lasted between 42 and 142 min, for an average of 73 min. In line with Strauss and Corbin (1998), we applied the scheme of open, axial, and selective coding to analyze our data—a scheme commonly employed in marketing studies (e.g., Challagalla et al. 2014; Malshe and Sohi 2009; Ulaga and Reinartz 2011). Although coding stages are always applied recursively (Strauss and Corbin 1998), we substantiated them chronologically. Table 3 lists zero-order, first-order, and second-order categories that emerged from this coding scheme procedure.

First, during open coding, we analyzed the data line-by-line to identify relevant concepts based on the actual language participants used and then grouped concepts related in meaning into zero-order categories (e.g., information transparency focus, see Table 3). During the second, axial coding stage, we contextualized the zero-order categories with supplementary literature, searched for relationships among these, and, as a result, reassembled them into first-order categories (e.g., experiential response orientation, see Table 3). In contrast with the descriptive zero-order categories, first-order categories are theoretically abstract categories developed by the researcher (Nag and Gioia 2012). Finally, during the third, selective coding stage, we further regrouped the first-order categories by distilling three second-order, so-called core categories of CEM (e.g., cultural mindsets, see Table 3). Selective coding thus serves as the main vehicle for integrating all categories coded during the research procedure into a unifying framework and for defining the object under investigation. Selective coding further involves the elimination of a few categories that fit poorly when analyzing the data specifically with respect to the identified second-order categories (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Similar to prior work (Tuli et al. 2007; Ulaga and Reinartz 2011), we eliminated categories at this stage if they were not applicable beyond specific contexts, such as service, online, and retailing, or mentioned by multiple participants.

During the coding procedure, we constantly compared the emerging categories (Strauss and Corbin 1998) with the following research streams for supplementation purposes: CE (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009), CEM (Patrício et al. 2011), multichannel management (e.g., Van Bruggen et al. 2010), integrated marketing communications and corporate identity (e.g., Simões et al. 2005), market orientation and capabilities (e.g., Day 2011), CRM (e.g., Boulding et al. 2005; Payne and Frow 2005), and articles on the pending future of the marketing concept (e.g., Webster and Lusch 2013). Table 3 indicates which zero-order categories have been supplemented by extant marketing literature and research.

At the end of this procedure, we distilled a three-tiered grounded theory framework of CEM that represents the overall result of our research. However, we made minor refinements to it during the trustworthiness assessment of our results.

Trustworthiness assessment

We applied principles of data and researcher triangulation to ensure the general trustworthiness and credibility of our results (Lincoln and Guba 1985). For data triangulation, we constantly compared field data with related research streams. Moreover, according to the principle of refutability as a quality criterion of qualitative research (Silverman and Marvasti 2008), we sought to refute the coded categories and relationships by obtaining a broad sample of firms representing a wide diversity in size and consumer industries engaging in CEM (for a similar procedure, see Homburg et al. 2014; Malshe and Sohi 2009). We observed that most of our categories were transferable across firm size and industries (Lincoln and Guba 1985), though differences existed with regard to the emphasis on single categories of CEM, to which we come back to later in the study. For researcher triangulation, two scholars conducted each coding stage independently. They discussed and integrated the coding plans after each coding stage, running common checks on internal consistency (Ulaga and Reinartz 2011). To further enhance the confirmability of our results (Lincoln and Guba 1985), we first asked two independent judges who were unfamiliar with the study to code the verbatim data of 20 randomly selected interviews into the coded categories. The interjudge reliability, assessed according to the proportional reduction in loss measure, reached 0.78 and thus is above the 0.70 threshold recommended for exploratory research (Rust and Cooil 1994). Second, we checked for respondent validation by asking the participants to provide written feedback on a report of the results. Of the 25 responding participants, 19 indicated their strong overall agreement with the results, and six suggested refining a few definitions of coded first-order categories. Third, we presented and discussed the results in two workshops with 21 doctoral researchers and five professors, who were unfamiliar with this research project, to continually refine our results.

Conceptual and theoretical foundations of CEM

To develop a generalizable, industry-spanning conceptualization of CEM, it was, for the purpose of this study, crucial to first agree on a generalizable understanding of the CE as its main action object (Strauss and Corbin 1998). We therefore draw on the following generalized definition of CE (adapted from Brakus et al. 2009; Verhoef et al. 2009): CE is the evolvement of a person’s sensorial, affective, cognitive, relational, and behavioral responses to a firm or brand by living through a journey of touchpoints along prepurchase, purchase, and postpurchase situations and continually judging this journey against response thresholds of co-occurring experiences in a person’s related environment. In this regard, a touchpoint represents any verbal (e.g., advertising) or nonverbal (e.g., product usage) incident a person perceives and consciously relates to a given firm or brand (Duncan and Moriarty 2006).

Our main research results suggest that CEM is a firm-wide management approach that entails three main categories: a firm’s (1) cultural mindsets, (2) strategic directions, and (3) capabilities. With these second-order categories of our grounded theory framework (see Table 3), we define the concept under investigation as follows: CEM refers to the cultural mindsets toward CEs, strategic directions for designing CEs, and firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs, with the goals of achieving and sustaining long-term customer loyalty. In the following, we outline each of the second-order categories and then introduce the overall theoretical underpinning of this three-tiered understanding that we consider most appropriate.

First, our data suggest that CEM is an issue of corporate culture, whereas nascent literature focuses on CEM methods or processes (e.g., Patrício et al. 2011). Emphasizing a CE culture in contrast with other corporate cultures, the CEO of an online retailer noted (ID 41):

The customer experience is the object of our enterprise. We get our customers on board. The customer is our partner. We are neither product nor customer-oriented; we are customer-experience oriented.

The marketing head of a telecommunications provider (ID 37) similarly stressed a CE culture:

Customer experience management is the reversion of our mindsets that must be learned across the firm with an extreme effort. The organization has to adapt to the logic of customer experiences, which for us has become a central approach to finally realize our mission of being a customer-centric firm.

Specifically, as illustrated in Table 3, we derive three cultural mindsets toward CEs: experiential response orientation, touchpoint journey orientation, and alliance orientation.

A firm’s cultural mindsets refer to mental portrayals managers use to describe their competitive advantage (Day 1994). If a certain mindset, for example the cultural mindset of MO (Narver and Slater 1990), disseminates across the organization and actually drives the evolvement of organizational processes (Day 1994; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), it is an “intangible entity that would be a resource” (Hunt and Morgan 1995, p. 11).

Second, our data suggest that CEM involves a set of strategic directions for designing CEs. Echoing the distinction between a cultural and a strategic design perspective on CEM, the marketing strategy director of an automotive firm (ID 3) elaborated,

For us, experience management is a matter of perspective (…). We need to revolutionize the mindsets of our marketers. They must understand what customer experience means, how to realize customer centricity, how to work with a touchpoint structure. [Then] we need customer experience designers, changes need to be done in the organization, in our strategies, in our way we organize marketing (…).

Research on service experience design confirms that the main purpose of CE design is to enhance customer loyalty—in other words, the customers’ intentions to live again through a touchpoint journey of a given firm or brand by transitioning from postpurchase to prepurchase. Commenting on this function, the CEO of a food retailer (ID 24) said,

Customer advocacy is our highest goal. We do not want customers who just buy our single products. (…) We want them to engage with us at many different points along their daily life (…) to engage with our holistic idea and concept of food selection, delivery and cooking.

Specifically, we derive four strategic directions for designing CEs: thematic cohesion of touchpoints, consistency of touchpoints, context sensitivity of touchpoints, and connectivity of touchpoints (see Table 3). Importantly, these directions pertain to customers’ touchpoint journeys as the object of strategic decision making, thus capturing the loyalty determining valence of CEs as they are evolving “within a certain time frame” (Brakus et al. 2009, p. 66). A firm’s strategic direction refers to a set of organization-wide guidelines on market-facing choices. Instead of cultural mindsets that mainly influence the behavioral traits of employees on an organization-wide level, strategic directions have a more direct effect on different marketing tasks and the customer front end (Challagalla et al. 2014), resulting in the realization of the customer–firm exchange. As such, a firm’s strategic directions represent intangible, exchange-based resources (Hult 2011; Kozlenkova et al. 2014; Wang and Ahmed 2007), if they can drive marketing tasks to the strategically desired customer–firm exchange.

Third, our data distill four central firm capabilities of CEM. These can be understood as the process-oriented manifestation of the other two CEM categories. In the words of the customer service manager of a consulted insurance provider (ID 21),

For me, customer experience management involves two things. First, it’s a design-oriented mindset of doing things from the perspective of the customer. Second, it involves seizing this mindset across the entire firm by introducing certain strategies, processes, and methods.

We found that the identified CEM capabilities interact with each other to continually renew CEs over time. The CEM director of a recently restructured telecommunications provider (ID 35) directly illustrates this central aspect of our derived CEM conceptualization:

Our new claim is “love it–change it–leave it.” We say it’s totally normal that with any new touchpoint design, not everything can be perfect. So we just start to redesign it, and in the worst case, we leave an idea behind us. As long as we work along the boundaries of our strategic guidelines, this does not have any negative consequences, the very opposite is true!

The finding that CEM involves the continual renewal of CEs indicates that in today’s highly competitive consumer markets (Wiggins and Ruefli 2005), CEs are “fleeting and continually changing over time” (Chandler and Lusch 2014, p. 7). The identified CEM capabilities therefore contribute to the continual design and redesign of CEs to achieve and sustain customer loyalty in dynamic market environments. Reflecting this long-term customer loyalty aspect of CEM, the marketing director of a sports apparel manufacturer (ID 5) asserted,

We want to play an active and bigger role in our customers’ life (…). It is an invitation for the long-term, not a single offer (…). We invite our customers to join the experiential world of our brand (…).

Specifically, we derive four firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs: touchpoint journey design, touchpoint prioritization, touchpoint journey monitoring, and touchpoint adaptation (see Table 3). A firm capability refers to an organizationally embedded pattern of processes and routines (Day 2011; Helfat and Lieberman 2002), commonly representing an intangible resource in research (e.g., Kozlenkova et al. 2014; Makadok 2001).

In summary, we derive a three-tiered CEM conceptualization that entails the three intangible resource types of cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities. In the remainder of this study, we therefore refer to the term resource instead of categories when elaborating on our grounded theory framework (see Table 3). Regarding the overall theoretical underpinning of this three-tiered understanding, we follow the tradition of nascent CEM research that mainly draws on the theoretical premises of service-dominant logic (see Table 1). We extend prior research by combining the premises of service-dominant logic with the tenets of the resource-based view in marketing and those of dynamic capabilities.Footnote 1

Specifically, we identified the theoretical view on hierarchical operant resources in marketing (Kozlenkova et al. 2014; Madhavaram and Hunt 2008) as the appropriate underpinning of our grounded theory framework of CEM. Operant resources are, according to one central premise of service-dominant logic, intangible resources that create or act on other resources (i.e., skills and knowledge of individual employees or corporate cultures of firms; Vargo and Lusch 2008). In the context of the resource-based view, Madhavaram and Hunt (2008, p. 67) propose a “hierarchy of basic, composite, and interconnected operant resources.” Specifically, as Table 3 illustrates, we argue that CEM is an operant third-order resource comprising the three second-order resources of cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities that themselves represent an interconnection of specific first-order resources (Madhavaram and Hunt 2008). This theoretical view suggests that a third-order resource in marketing is highly difficult to copy and can significantly increase the sustainability of competitive advantages (e.g., Madhavaram and Hunt 2008; Wang and Ahmed 2007). This suggestion reinforces our derived understanding that CEM primarily aims to achieve and sustain long-term customer loyalty for competitive advantages and long-term firm growth.

In addition, we found that the four identified CEM capabilities disseminate requirements, data, or propositions to one another. As such, they interact in a potential system with different cyclical paths. Consequently, the corresponding second-order resource of CEM must be understood as a dynamic capability. This is because, from a theoretical perspective, a dynamic capability may subsume several first-order capabilities (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Wang and Ahmed 2007), and, per established definition, it enables the firm to “modify itself so as to continue to produce, efficiently and/or effectively, market offerings for some market segments” (Madhavaram and Hunt 2008, p. 69). Therefore, we combine the tenets of hierarchical operant resources and those of dynamic capabilities by suggesting that the dynamic capability for continually renewing CEs itself is a constituent part of a third-order CEM resource that sustains competitive advantages through long-term customer loyalty.

Grounded theory framework of CEM

Building on the foundations of CEM, we next outline each first-order resource within our framework as it emerged from our data. To account for our research procedure of having iteratively integrated field data and supplementary literature, we introduce each first-order resource by the following structure: description, exemplification with the help of representative field quotes, and verification with the help of literature evidence. Table 4 provides an overview of the key features of each first-order resource.

Cultural mindsets toward CEs

Experiential response orientation

This mindset refers to the firm’s acknowledgment of and orientation to eliciting multiple experiential responses at single touchpoints. As the head of business development of an apparel manufacturer and retailer (ID 4) explained,

In our parents’ world, satisfaction meant to just deliver a product that works. But today, we must and do address a broader phalanx of issues: Does it [apparel] fit me? Am I attracted to the store design? Do I get compliments? How was the sales person dressed? Was he cool or not cool?

Knowing that the effects of, for example, sensorial and affective stimulation on revenue might not be measurable directly, firms similarly asserted that they elicit such responses by means of cultural mindsets. In the words of the marketing director of an energy provider (ID 11),

We must just internalize that the customer experience is the core of our business. However, in our daily work, this can become difficult. Take our personalized birthday cards we send every customer by mail. It is difficult to measure their direct impact on customer loyalty, but we know that they evoke delight and gratitude. We could easily decide to save on these cards in economically difficult times. But no! No, because we have understood what it means to provide customer experiences.

This mindset is also reflected in how firms measure customer responses in general. Notably, we found that more than two-thirds of our consulted CEM firms have proceeded from customer satisfaction measures to assessing the net promoter score, which represents a simplified measure of customer loyalty based on the overall quality of CEs (Keiningham et al. 2007) and, thus, the multiple CE responses. These involve cognitive, sensorial, affective, relational (e.g., gratitude, intimacy), and behavioral responses to a given firm or brand (e.g., Brakus et al. 2009; Gentile et al. 2007; Lemke et al. 2011).

Touchpoint journey orientation

The participants similarly referred to the importance of establishing touchpoint journeys across prepurchase, purchase, and postpurchase situations as the main object of market-facing decision making. This mindset captures the sequential character of CE perceptions, with experiential responses evolving over time (see Ghoshal et al. 2014; Verhoef et al. 2009)—the verb form of the term experience. As the consulted marketing director of a home appliance manufacturer and retailer (ID 6) asserted:

The customer experience includes every point where the customer comes into contact with our brand. This means before purchase, when the customer acquires information—whether at our partners’ point of sales or on our homepage; during purchase with regard to promotion, payment, and delivery; and after purchase, when the customer has some questions or if he needs spare parts. All these touchpoints add to the customer experience. The success factor is to consider all of them in relation to one another and to develop a touchpoint journey logic that overcomes departmental silo mentalities within our company.

The head of business development of an information and communication technology (ICT) provider (ID 34), for example, commented on an educational map that manifests a cultural touchpoint journey orientation within the consulted firm:

The WHAT phase, our first phase, entails how customers perceive what we are offering, in ads, stores, or commercials. In the FIND phase, the customer already has some awareness of our products. Now, he wants to find our products. GET is the actual purchase phase. The SETUP phase is the most important moment of truth for us, as it’s not trivial in our environments to install the products. Afterwards comes the USE phase and after that the PAY phase, followed by the GET HELP phase.

Whereas extant research focuses on firm-centric categorizations, such as product, service, and communication encounters (e.g., Lemke et al. 2011), the touchpoint journey notion is more universal and captures what actually happens from an individual’s point of view over time (Zomerdijk and Voss 2010). A main advantage of a touchpoint journey orientation is the ability to manage all touchpoints in the marketplace together and, thus, to more easily address important moments of truth along that journey (Ghoshal et al. 2014).

Alliance orientation

Several consulted firms stressed the relevance of alliances with other firms. This proneness helps firms better align a person’s different touchpoint journeys, and thus CEs, in his or her related environment. Consider, for example, the following quote of the marketing director of an automotive firm (ID 1):

When we want to move closer towards the life experiences of our customers, we must think about multimodal mobility, about how we can integrate services such as car sharing into a multivendor system (…). But to enter that game, we must strive towards strategic alliances and joint business modeling.

The marketing strategy manager of a telecommunications provider (ID 36) highlighted this mindset as a unique aspect of firms engaging in CEM:

Three years ago, we started to address the topic of market ecosystems. Around the entertainment experiences of our customers, we continually check how to improve the experiences of our customers. This implies entering into more partnerships with other firms. Many firms are not ready yet to work with such an attitude, but to think in market ecosystems has become a central attitude in our firm.

In our field data, we found plenty of evidence of alliances aiming to align different touchpoint journeys in a person’s related market environment. For example, an airline cooperates with an innovative taxi booking application to provide its customers a fast and payless taxi transfer after landing; an apparel manufacturer cooperates with a consumer electronics firm to improve application-based systems for tracking training progress; and an energy provider cooperates with house moving service providers for streamlined processes.

Notably, recent studies indicate that the evolvement of CEs depends on response thresholds resulting from co-occurring experiences with other competing and non-competing firms or brands in the marketplace. These different CEs co-determine whether to further engage with the touchpoints of a given firm or brand. To address this aspect of the CE concept, Webster and Lusch (2013) and Chandler and Lusch (2014) accordingly state that firms should increasingly address the interdependencies between different customer roles.

Strategic directions for designing CEs

Thematic cohesion of touchpoints

This coded category refers to the direction to extend the firm’s core touchpoints along a brand theme that promises to provide customers a certain lifestyle or activity with the help of an interrelated set of multiple touchpoints. For example, whereas many online apparel retailers face the challenge of high return rates, one of our consulted retailers has strategically pursued the brand theme of “outfitting” to reduce return rates to a minimum. Along this theme, it provides touchpoints such as podcasts with advice on styling and apparel organization, online configurators for ordering packages with entire outfits, and inspirational fashion newsletters. Similarly, a consulted energy provider has envisioned the brand theme of “sustainable energy” and has added thematically relevant touchpoints to the market. In the words of the interviewed head of sales (ID 12),

When we tried—only a number of years ago—to improve our experiential theme world, we were focusing so much on our actual touchpoints that we forgot this: the before and the after. (…) What we are doing now is to provide a lot of additional touchpoints for adding value to our theme world (…), establishing an online shop for sustainable home appliances, a blog on green energy, information events on our technology, and online energy calculators, just to name a few.

Elaborating on the touchpoint-spanning character of brand themes, the director of a coffee manufacturer and retailer (ID 47), who has envisioned the theme of “coffee indulgence,” said,

Everyone talks about thematic storytelling, but we have a deeper understanding of what that means. It is about the role our brand should play in the daily life of our customers, about the lifestyle we enable with our many touchpoints.

Pine and Gilmore (1998, p. 98), the founders of the “experience economy,” state that for outstanding experiences, the customer must engage in touchpoints with a brand theme “in a way that creates a memorable event.” Whereas these authors associate brand themes primarily with single touchpoints, such as flagship stores or themed restaurants, our consulted firms, however, have a more encompassing view that is most likely comparable to the applied writings on how to conduct branding in the context of CEM (e.g., Schmitt 2003).

Consistency of touchpoints

Furthermore, when referring to CEM, firms highlight the need to thoroughly design and stick with their corporate identity elements across multiple touchpoints to ensure similar, loyalty-enhancing experiential responses over time. The head of marketing of a consumer electronics firm (ID 8), for example, emphasized the necessity of customers perceiving the corporate identity consistently across all touchpoints:

Our primary brand identity centers on simplicity and cleanness. Only communicating this image is not enough, it must be perceived consistently in our stores, at our web shop, during product usage (…), in all incidents our customer comes into contact with our organization. We can’t allow any gap between our defined identity and the actual experiences of our customers.

Similarly, the head of marketing and sales of a home appliance manufacturer (ID 9) asserted,

Our image must be visible at every point of contact. Even in our shop-in-shop stores we take care that our image is consistent with our online channels and other points of contact. This involves corporate design and how we interact with our customers–everything must be perceived in a similar style.

The integration of our field data with the well-established research stream on integrated marketing communications, corporate identity, and multichannel management yielded the following facets of touchpoint consistency: design language (e.g., Simões et al. 2005), interaction behavior (e.g., Sousa and Voss 2006), communication messages (e.g., Kitchen and Burgmann 2004), and process/navigation logic (e.g., Banerjee 2014). Research has examined the effects of such corporate identity elements on market performance (Simões et al. 2005), highlighting their relevance in generating loyalty-enhancing customer responses.

Context sensitivity of touchpoints

Our consulted CEM firms stressed the increasing relevance of addressing and optimizing touchpoints to be sensitive to customers’ situational contexts or the touchpoints’ specific features. The chief experience officer of an online retailer (ID 40), for example, elaborated on the context sensitivity of its online shop:

We have customers who wish to directly submit their customer ID for reordering products. But we also have new customers who enjoy browsing through our shop. In the ideal case, prospective and current customers should be provided different touchpoints. How can we realize this? Well, our strategic projects are all about creating use-case specific landing pages, different paths to purchases, and advertisements highly customized to individual browsing behavior.

The marketing director of a financial service and insurance provider (ID 15) emphasized that the context sensitivity of touchpoints is increasingly a matter of strategic decision making:

In our strategy, we emphasize that the overall form of consuming will change. Those firms that offer customers the best overview, provide proactive updates for insurance policies if the customers’ life situation has changed, and generate data-driven, personal reasons for contact instead of mere newsletters or ads will win. We are currently positioning ourselves against this background.

Nascent research on service experience design (Fig. 1) indirectly supports context sensitivity by introducing methods of mapping customer activities against all potential touchpoints for identifying optimization potentials (see also Payne et al. 2008). According to our field data, the context sensitivity of touchpoints can make touchpoints more informative (e.g., e-commerce service for comparing competing product alternatives), convenient (e.g., child-care services at the point of sales), (self)-customized (e.g., proactive mailing reminding the customer to update household insurance after a move), or flexible (e.g., the opportunity to arrange online appointments with field service staff; opportunity for a desired date with parcel delivery).

Connectivity of touchpoints

Against the background of an abundance of new digital touchpoints, marketers strive to functionally integrate touchpoints across online and offline environments for seamless transitions. Consider the following quote of the CEM director at a mail services firm (ID 50), who cooperates with e-commerce sites in this regard:

A few months ago, we started cooperating with several e-commerce communities. Customers now have the opportunity to print out their package label directly after having closed the deal, with one click. For us, these functionalities, reducing the complexity for customers, are crucial.

Another example refers to an ICT provider who stressed the need for touchpoint-spanning personalization to help customers switch devices without re-entering data. Similarly, the marketing director of an energy provider (ID 11) indicated the need to integrate customer data across touchpoints to avoid customers’ re-legitimization:

Today, you have to better connect your touchpoints (…). The customer purchases a tariff at our store, but expects support via phone or online chatting without explaining his entire story or problem again and again. (…) These are situations our industry is not good at, for us a perfect point of differentiation.

In extant marketing research, we find several examples that echo touchpoint connectivity. These include providing an online overview of in-store stock or store maps (e.g., Bendoly et al. 2005); enabling a single view on the customer contact history across touchpoints (e.g., Payne and Frow 2005); making vouchers valid across offline and online touchpoints; and enabling customers to order online but pick up, return, or pay offline (e.g., Banerjee 2014).

Firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs

Touchpoint journey design

We found that our participants design potential touchpoint journeys from the consumer perspective as a means for business planning and modeling. Echoing this perspective, the sales head of a telecommunications provider (ID 33) noted,

Designing an experience as a procedural chain can’t just be coordinated across functions. It must be done at a central place with strategic oversight where all functional threads come together, without, for example, favoring any single channel because of political reasons within the company.

We argue that firms conduct touchpoint journey design to govern all potential touchpoints in the market and to devise more functionally oriented marketing capabilities, such as product management, sales, order fulfillment, communications, and complaint management (Day 1994; Vorhies and Morgan 2005). Specifically, firms disseminate requirements for the implementation of new touchpoints and the modification of touchpoints that might be affected. In the words of the customer strategy manager of an airline (ID 51),

There was no one to think about how our service chain looks like in total. Every department has made their own choices based on their own knowledge and ideas, but there was no integration. During the last years, we have restructured our firm several times, and since the last reorganization, we have a new central department called “customer experience design,” which considers the entire process from A to Z and which has the legitimacy to give directions to different functional departments.

This capability is in accordance with the nascent research on service experience design (Fig. 1), though it takes a more comprehensive perspective of the entire touchpoint journey from prepurchase to postpurchase (see Verhoef et al. 2009). Furthermore, Day (2011) indirectly confirms the finding of a superordinate capability of touchpoint journey design by stressing that a firm’s orientation to the total CE (thus, touchpoint journey) requires marketing to become a top management responsibility in business planning and modeling.

Touchpoint prioritization

This capability refers to directing the continuous implementation and modification of touchpoints and, thus, the continuous (re)allocation of monetary, technical, and human resources. This is because one of the main implications of the strategic directions of CEM is a firm’s ability to continually develop and modify single touchpoints in the short run without going through business planning, such as touchpoint journey design, each time. Commenting on this independence of continually adapting touchpoints, the business development manager of a mail services firm (ID 52) said,

The executive board has given us the freedom to adapt touchpoints continuously based on interpreting our market research results, as long as we stick to the overall strategy. (…) We shift resources independently if we see that competitors start to outperform us at certain points. Touchpoints are not employed anymore if our data reveal a certain pain point, which we then can redesign rapidly.

To balance the requirements of touchpoint journey design with the autonomy of developing and modifying touchpoints in the short run, firms draw on a data-driven prioritization scheme to allocate resources to a given planning period (see Payne and Frow 2005). As the director of customer engagement of a health care manufacturer (ID 30) noted,

To decide when and which touchpoints to implement or change, we have to know which touchpoints are the most important ones; how relevant are they for our customers? Where do we have an urgent need to change a touchpoint? How well do our competitors perform at similar touchpoints?

Challagalla et al. (2014) allude to this capability as solving the “consistency-flexibility conundrum,” with touchpoint journey design providing high-level guidance on functional decision making, but leaving execution details to the touchpoint prioritization capability.

Touchpoint journey monitoring

The functionally oriented capabilities that change or implement a touchpoint according to touchpoint prioritization also commonly collect performance indicators. Most of our firms, however, coordinate and depict the collection of performance indicators in accordance with their touchpoint journey orientation. We find that firms may realize this coordination effort by establishing a dedicated monitoring capability with cross-touchpoint responsibility. As the CEO of an online retailer (ID 43) highlighted,

One of our teams has the responsibility to combine and sort specific performance indicators along our customer journeys. How much website visitors do we have, how many customers access our newsletter, how long do they navigate through our e-commerce platform? It is crucial to have people to assess and visualize the customer journey; it allows us to make stepwise, autonomous improvements.

Likewise echoing touchpoint journey monitoring, the vice president of a home appliance manufacturer and retailer (ID 7) explained an approach of mirroring “experience chains”:

We mirror our experience chain with target values. How often does the customer have to consult an employee in our shops? How many products are purchased online? How often are our online banners clicked? What is the average waiting time at our call center?

Extant research does not reflect this capability directly. However, in their applied writing, Berry et al. (2002) specify the systematic depiction of CEs with the help of an “experience audit,” and researchers have stressed the importance of comprehensiveness in marketing performance measurement (e.g., Homburg et al. 2012; Payne and Frow 2005).

Touchpoint adaptation

Several firms have created a capability to enrich and interpret the data of touchpoint journey monitoring with in-depth customer research. In contrast with induced market-sensing capabilities (Day 2011), however, this capability mainly creates concrete propositions for the development or modification of touchpoint(s) (journeys) on a proactive basis. As the marketing head of a telecommunication provider (ID 37) explained,

One of our customer experience departments is called customer insight and prototyping. We continually interpret the given market insights we collect at the customer front end and then creatively work with that data for developing potential points of improvement. We collect qualitative market insights, design prototypes of use cases, validate these prototypes in customer workshops, and thereby maintain a direct dialogue with customers in a customer advisory board.

Similarly, the CEM manager at a financial service and insurance provider (ID 19) said,

We try to dig deeper into the life of our segments. Not only do we conduct classical market research, but we also send our employees to the point of sales to face real customers. What we also do is to send our employees into households to understand typical situations and problems of our segments. With such insights, we then proactively create prototypes for new products and service chains.

As these quotes reflect, firms put special emphasis on collecting observational data (Hui et al. 2013) and deploying dedicated customer voices (Urban and Hauser 2004), such as customer advisory boards and customer workshops. These in-depth customer insights contribute to obtaining a deeper understanding of single touchpoints and their broader market contexts, allowing for the proactive development of highly customer-centric touchpoint propositions.

These propositions must then be disseminated across the firm to be leveraged effectively. We argue that propositions for the development of incrementally new touchpoints and the modification of single touchpoints are disseminated across the capability of touchpoint prioritization for the independent implementation underneath business planning and modeling. As the interviewed vice president of a cruise line (ID 49) commented,

Implementing customer feedback loops, conducting depth interviews, and observing customers on board must not degenerate into tokenism. A firm needs the courage to implement a continuous change management that takes advantage of this data. Our whole change and optimization management is adapted to leveraging that data. It can’t be just a “we-ask-everything-but-continue-as-usual” approach.

Propositions for the development of radically new touchpoints, such as product or service innovations, in turn, must be orchestrated with the portfolio of other touchpoints for their successful deployment (see Brown and Eisenhardt 1997). Thus, we argue that these propositions primarily disseminate across the capability of touchpoint journey design, closing the full dynamic system of capabilities for continually renewing CEs in the long run.

Contingency factors of CEM

How does CEM manifest itself across various types of firms? In the preceding sections, we presented a generalized and empirically grounded picture of CEM. However, our field data showed some differences in terms of firms’ emphasis on the three main resources of CEM (cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities). To systemize these CEM patterns, we identified two pertinent criteria grounded in our field data.

The first dimension is firm size. Consistent with other marketing studies (O’Sullivan and Abela 2007), we classified it as the firm’s number of employees. We split firm size into small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs, up to 250 employees) and large enterprises (more than 250 employees; UN Statistics Directorate 2005). The second dimension is the exchange continuity of the firm’s core business model, split into two extremes: transactional and relational exchange (e.g., Ferguson et al. 2005; Ganesan 1994). Transactional exchange “involves single, short-term exchange events encompassing a distinct beginning and ending,” whereas relational exchange involves exchange events that are linked together over time and represent an “ongoing process” of exchanges that trace “back to previous interactions” (Gundlach and Murphy 1993, p. 36). We classified our firms according to whether their revenue-dominating core business model is transactional or relational. To do so, we referred to participants’ statements and also consulted mainly financial data on the firms’ business models. We relied on checks of internal consistency between the two coding researchers and further assessed the trustworthiness of our classification by conducting a respondent validation, with participants agreeing with our classification (for a similar procedure, see Malshe and Sohi 2009).

There was no evidence of other contingency factors of CEM, such as product/service dichotomy, competitive intensity, or any other context factors of specific industries or firm type. We found that when analyzing our data specifically with respect to the four quadrants of the identified typology, they differed significantly in terms of their emphasis on the three main CEM resources. We assessed these differences with Z tests of proportion (Tuli et al. 2007). On the basis of the significant differences (ps < .05; one-sided), we describe four distinct CEM patterns and further highlight the most salient cultural mindset, strategic direction, and firm capability for each pattern. Figure 3 illustrates the frequency of mentioned and attributed themes (3a) that resulted in the disclosure of the following CEM patterns (3b).

CEM pattern 1

The consulted SMEs with a transactional core business model highlighted cultural mindsets toward CEs (83%) over CEM capabilities (16%, see Fig. 3a). Most often, co-founders are committed to and internally leverage a certain CE vision that, when realized, elicits customers’ experiential patronage and long-term loyalty. Because transactional markets are very competitive, this approach is a main driver of many start-ups for securing market niches through innovation and differentiation. E-commerce providers with customizable product offerings or innovative mobile repair shops on call exemplify this CEM pattern.

According to the firms’ CE vision, participants highlighted experiential response orientation and commonly asserted to manifest this vision into every single touchpoint, highlighting consistency (Fig. 3b). The firms’ focus on consistent experiential responses at different touchpoints explains why the participants mainly referred to touchpoint monitoring for identifying optimization potentials. Therefore, we refer to this pattern as SMEs that build on executives’ vision of an outstanding CE, convey a consistent touchpoint journey, and stress the continual monitoring and optimization of customers’ experiential responses.

CEM pattern 2

In comparison with pattern 1 (16%), the consulted SMEs with a relational core business model clearly highlighted firm capabilities of CEM (100%, see Fig. 3a). As stated by the service-dominant logic of value co-creation (Vargo and Lusch 2008), we presume that these firms highlight CEM capabilities to continually integrate their knowledge and expertise with customer resources. Career consultancy service providers or innovative energy providers that consult on and install self-supplying energy appliances exemplify this CEM pattern.

According to this co-creative focus, participants highlighted experiential response orientation (Fig. 3b). The most salient CEM capability among these firms was touchpoint adaptation in close cooperation with customers (e.g., by customer advisory boards, pilot testing). Participants did not highlight strategic directions of CEM, except the context sensitivity of touchpoints, presumably because firms’ touchpoints are mainly co-created. Therefore, we refer to this pattern as SMEs that mainly leverage their focus on experiential customer responses to continually design and adapt touchpoints in purposeful cooperations.

CEM pattern 3

The consulted large enterprises with a transactional core business model mainly focused on strategic directions (73%) and firm capabilities (87%, Fig. 3a) when referring to CEM. With firms growing in transactional markets, vested with extended financial resources, we presume that the focus on cultural mindsets is increasingly being replaced by the necessity of touchpoint ubiquity and the continual renewal of CEs to keep market awareness high in competitive markets. This may also explain why the cultural mindset toward experiential responses is displaced by touchpoint journey orientation as the most salient mindset. Lifestyle-oriented food retailers such as Nespresso or fashion branding and multichannel-oriented retailing, as done by Nike, exemplify this CEM pattern.

With regard to the aim of touchpoint ubiquity and brand awareness, participants similarly focused on telling comprehensive, cross-touchpoint brand stories, highlighting the strategic direction of thematically cohesive touchpoints (Fig. 3b). Given the steady increase of new, potential touchpoints (Day 2011), such as pop-up stores, social media channels, mobile applications, and interactive terminals, we found touchpoint prioritization to be the most salient CEM capability. Therefore, we refer to this CEM pattern as large enterprises that leverage the opportunities of touchpoint ubiquity by proposing thematically cohesive touchpoint journeys and frequently prioritizing new, promising touchpoints.

CEM pattern 4

Large enterprises with a relational core business model showed the strongest tendency to put equal emphasis on all three CEM resources (Fig. 3a). In comparison with pattern 2 (40%), the participants clearly stressed the role of strategic directions in CEM (85%). With firms growing in relational markets, we presume that the focus on co-creation is being replaced by the strategic necessity of designing elaborate touchpoint journeys in a mass market. In comparison with pattern 3 (40%), we further observe a return to the relevance of cultural mindsets toward CEs (80%), as firms are transitioning from transactional to relational business models. Digital wallet services as introduced by Apple, smart home initiatives as introduced by Google, or multimodal mobility systems exemplify this CEM pattern.

Most of these firms use the relational character of their (newly evolving) core business model to design elaborate journeys that integrate touchpoints of different firms and brands, thus highlighting alliance orientation as the main cultural mindset and connectivity as the main strategic direction of CEM. Regarding firm capabilities, participants in this CEM pattern reflected all four firm capabilities nearly equally, which clearly reflects a dynamic system of continual renewal, though touchpoint journey design—as an important method to depict the interdependencies between touchpoints of different firms—was most salient. Therefore, we refer to this pattern as large enterprises that highlight the continual (re)design of elaborate and potentially firm-spanning touchpoint journeys in mass market networks.

Research implications and theoretical propositions

In the following, we discuss our findings with regard to our third research question of how CEM demarcates from other marketing (management) concepts. As a result, we offer four propositions with regard to the derived (1) grounded theory framework, (2) identified cultural mindsets, (3) strategic directions, and (4) firm capabilities of CEM. Table 5 provides an overview of the demarcation between MO and CRM, representing the most prevalent marketing concepts (Boulding et al. 2005), and the derived CEM conceptualization. Figure 4 illustrates the resulting theoretical propositions and corresponding future research directions.

Grounded theory framework of CEM

This study develops a marketing management concept as a higher-order resource of cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities. As such, we first propose that CEM represents a comprehensive marketing management concept, whereas extant research shows only indirect evidence for the relevance of this triad in marketing management (see Table 5). The MO concept is conceptualized through either cultural mindsets (Narver and Slater 1990) or behaviors and capabilities (Day 1994; Jaworski and Kohli 1993), thus lacking a strategic perspective on concrete market-facing decision making. Instead, MO refers to norms and artifacts (Homburg and Pflesser 2000), which primarily guide the working attitudes of employees, hence influencing market-facing strategies only indirectly (Challagalla et al. 2014). CRM, in turn, is established as a strategic approach that guides effective CRM capabilities (Payne and Frow 2005; Ramani and Kumar 2008), thus largely ignoring attributes of corporate culture. The lack of CRM research at this point may be explained through its cultural tradition of regarding customer retention and profit maximization as the primary goals of CRM. Specifically, the common goal of CRM is to identify the profit maximizing configuration of initiating, maintaining, and terminating customer relationships (Reinartz et al. 2004), whereas CEM unfolds the culturally driven goal of achieving long-term customer loyalty and hence long-term firm growth by designing and continually renewing segment-specific touchpoint journeys. Notably, although the concept of MO has a tradition with regard to corporate culture research, it is also ascribed a rather exploitative mindset with a firm-centric focus on customer satisfaction and market performance (Day 2011), an issue we come back to momentarily.

Furthermore, we propose that the CEM triad of cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities systemizes and serves the implementation of an evolving marketing concept. In particular, we draw on and integrate more recent, supportive theoretical research to transfer our CEM framework to the implementation of an evolving marketing concept. By doing so, literature highlights the following aspects as being inherent to an evolving marketing concept: a firm’s (1) cultural market network mindset (e.g., Achrol and Kotler 2012; Cambra-Fierro et al. 2011; Hult 2011), (2) strategic design of potentially firm-spanning value constellation propositions (e.g., Chandler and Lusch 2014; Skålén et al. 2015; Webster and Lusch 2013), and (3) dynamic system of capabilities for the realization of organizational ambidexterity (e.g., Day 2011; Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008; Weerawardena et al. 2015). Figure 4.1 illustrates our first proposition that CEM represents a comprehensive management concept that systemizes and serves the implementation of an evolving marketing concept.

In the following subsections, we elaborate on the relationship between each operant resource of our grounded theory framework of CEM and the aforementioned aspects of the evolving marketing concept. We thereby explicitly address how CEM demarcates from the marketing management concepts of MO and CRM with regard to each operant resource.

Cultural mindsets toward CEs

This study introduces three cultural mindsets toward CEs: experiential response orientation, touchpoint journey orientation, and alliance orientation. We propose that these mindsets extend MO and CRM by being indicative of a firm’s cultural market network mindset (see Fig. 4.2)—that is, the mental model that “evolving into global business networks from the production end to the consumption end” (Achrol and Kotler 2012, p. 30) results in sustainable competitive advantages (Cambra-Fierro et al. 2011; Chandler and Lusch 2014; Day 2011; Hult 2011; Lusch and Webster 2011; Webster and Lusch 2013).

First, experiential response orientation extends MO’s customer orientation in terms of a detailed awareness that, today, sensing and responding to customer needs (Narver and Slater 1990) goes well beyond focusing on cognitive, affective (Oliver 1993), and relational customer responses to also entailing sensorial and behavioral customer responses (as separate dimensions). Firms with the most dominant experiential response orientation and, therefore presumably the best customer or brand assets, might act as the “nodal entity” (Achrol and Kotler 2012; Van Bruggen et al. 2010) in potential market networks. Second, alliance orientation extends MO’s competitor orientation in terms of a more collaborative way of acting toward other (non-)competing market players. Finally, touchpoint journey orientation extends MO’s cross-functional collaboration (Table 5) in terms of not regarding market data (Jaworski and Kohli 1993) as the object of collaboration but rather the realization of elaborate touchpoint journeys. This emerging orientation might, as a design scheme, facilitate the mapping of interdependencies between touchpoints of different firms and the development of market network–oriented value propositions, as we discuss next.

Strategic directions for designing CEs

This study introduces four strategic directions for designing CEs: thematic cohesion, consistency, context sensitivity, and connectivity of touchpoints. We propose that these four directions extend MO and CRM by illustrating how to design potentially firm-spanning value constellation propositions (see Fig. 4.3) that span different CEs or, in other words, diverse touchpoints of different firms or brands to realize a given activity, need, or desire (Patrício et al. 2011; see also Chandler and Lusch 2014; Golder et al. 2012; Lusch et al. 2010; Skålén et al. 2015). That is, we suggest that all four derived strategic directions are necessary to develop a value constellation proposition. Whereas the strategic direction thematic cohesion of touchpoints might determine the nature of a value constellation proposition, consistency, context sensitivity, and connectivity of touchpoints might guide how to concretely integrate touchpoints for such a proposition. The result could be socially desirable and sustainable value constellations (Webster and Lusch 2013)—for example, customers’ household management in smart grid systems or multimodal mobility services.

We propose that the strategic directions of CEM extend MO and CRM for the following reasons: As stated previously, we extend MO since the concept is largely silent on market-facing, strategic attributes of marketing management (Table 5). CRM, in turn, alludes to designing CEs by co-creating value for the “total buying experience, not just the core product.” In this regard, Payne and Frow (2005) claim that multichannel integration is the key element of CRM, which relates to our identified strategic direction of connectivity of touchpoints. Similarly, Ramani and Kumar (2008) highlight personalized customer interactions as another key element of CRM, which relates to our identified strategic direction of context-sensitivity. As such, we extend CRM by synthesizing, extending, and adding important strategic directions (thematic cohesion and consistency of touchpoints) and hence comprehensively illustrating how to design CEs and broader, potentially firm-spanning value constellation propositions in customer segments’ relevant market networks.

Firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs

Last, this study introduces four firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs: touchpoint journey design, touchpoint prioritization, touchpoint journey monitoring, and touchpoint adaptation. We found and conceptualized that these capabilities closely interact in a dynamic system. From this conceptualization, we propose that the identified firm capabilities of CEM extend MO and CRM by representing a dynamic system for organizational ambidexterity—that is, the synchronization and balancing of incremental and radical market innovations (Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008). Specifically, whereas extant management research provide a firm-, capability-, and employee-based perspective on how to realize organizational ambidexterity (Raisch et al. 2009), our CEM conceptualization offers an important fourth perspective by focusing on the interplay of different firm capabilities. As such, not single capabilities but rather the interaction patterns between different capabilities determine the distinction between incremental and radical market innovations or, in other words, market exploitation and market exploration (Vorhies and Morgan 2005; Weerawardena et al. 2015, see Table 5). Specifically, a short-term cycle for the continuous monitoring, proactive adaptation, and prioritization of single touchpoints pertains to rather incremental market innovations, whereas a long-term cycle for the business planning and design of entire touchpoint journeys involves the initiation and development of rather radical market innovations (see Fig. 4.4).

Recent research highlights the emerging relevance of organizational ambidexterity in marketing management and an evolving marketing concept (Day 2011; Menguc and Auh 2006; Vorhies and Morgan 2005; Weerawardena et al. 2015). However, extant views of MO and CRM do not fulfill this demand. From a capability perspective, MO is conceptualized as the effective use of market data through generating, interpreting, and disseminating relevant data within the firm (Jaworski and Kohli 1993). This view, however, “is biased toward an exploitative mind-set” (Day 2011, p. 188), as reflected by some attempts to capture a more explorative perspective of MO (e.g., Blocker et al. 2011; Narver et al. 2004). CRM, in turn, is primarily established as the data-induced process of planning, implementing, and monitoring customer relationships (Payne and Frow 2005). In contrast to the CEM capabilities of touchpoint adaptation and prioritization, however, the CRM concept lacks a mechanism of continual optimization. Furthermore, the concept is silent on the transition processes between capabilities of ICT-driven customer data collection and analysis (Jayachandran et al. 2005) and strategy making (Payne and Frow 2005). Thus, the CRM concept also has a rather reactive, exploitative character (Boulding et al. 2005). In their applied writing, Meyer and Schwager (2007) mirror this reactive character by differentiating CRM—focusing on the collection of historic customer data—from CEM—focusing on the generation of real-time insights of how customers perceive touchpoints to facilitate the exploratory identification of new market opportunities.

Although our qualitative research results provide only a starting point, we believe that marketing research could make a significant contribution to better understanding how to realize organizational ambidexterity by drawing on this new perspective of interaction patterns between marketing capabilities. This is because capabilities, instead of functions, are gaining momentum in marketing research (Day 2011; Hult 2011). Moreover, researchers have already stressed the importance of different capabilities working together effectively (Day 2011; Leiblein 2011; Vorhies and Morgan 2005), and we find evidence in both marketing (e.g., Weerawardena et al. 2015) and management research (e.g., Raisch et al. 2009; Wang and Ahmed 2007) that suggests that a higher-order dynamic capability is the right theoretical lens through which to capture organizational ambidexterity.

Managerial implications

We introduced CEM as a higher-order resource that entails cultural mindsets toward CEs, strategic directions for designing CEs, and firm capabilities for continually renewing CEs, with the goals of achieving and sustaining long-term customer loyalty. The concepts of CRM and MO, in contrast, do not provide an integrative view on cultural mindsets, strategic directions, and firm capabilities. Both concepts are further biased toward an exploitative, firm-centric focus on market performance and profit maximization. Practitioners involved in CEM must therefore be aware that this marketing management concept is a matter of firm-wide deployment, requiring to equally acknowledge all three resource types for its effective implementation. Marketers might stress the importance of a bottom-up process of transforming the firm’s corporate culture into a CE mindset, which can facilitate the coordination efforts of CE design, and might further search for corresponding executives’ support. Executives, in turn, might use their oversight to guide the establishment of a dynamic capability system and to foster the firm’s overall dedication to long-term customer loyalty.